Main Body

Chapter 11. Cleveland, 1979

There’s a point to working nights on an evening newspaper. You get to hear instant reactions from readers who have something to say about what they’ve just read in your paper. I think we had three reporters to answer the phones: one on sports, another doing police stuff and, for the time being – me.

Mostly it was just to hear we’ve got this wrong or that wrong, or that Cleveland Indians’ pitcher Rick Waits was having a better ERA (earned runs average) than pitcher Rick Wise, who was above him in the top spot on the team. Or was the caller getting the two mixed up? Waits? Wise? C’mon, Rick whoever!

But once in a while something quite surprising – and powerful – might show up.

I was half way through 18-months of this when the phone rang at 9pm and a slow, tired, elderly male voice told me he didn’t have long to go but thought somebody ought to do something about “all dese soup ponds” in Painesville Township. “Dey stink when its dry.”

‘Soup ponds,’ was colloquial for the waste lakes at the Diamond Shamrock Corporation’s chemical plant in Painesville Twp, Lake County, 28 miles east of Cleveland next to Lake Erie. I didn’t know anything about it, had never been there, and only vaguely knew it had closed abruptly two years earlier, leaving 1,200 employees – the largest work force in the area – to look elsewhere for work.

“Dey owe us,” he said. “But dobody’s been by.”

I struggled to understand him, and said so. “Oh, it’s de dose…. nose,” he said with an effort. I heard a slight whistling sound as he spoke. “Got a hole in it …..from de chromate.”

Thus began a six-week investigation of the medical, environmental, community and business legacy of just one old, collapsed industrial plant in America that seemed to epitomize them all. At 1,100 acres the Diamond Shamrock industrial complex was one of the largest ‘brownfields’ in the United States: an abandoned, apparently dead, unproductive place. It would cost a fortune to restore and heal, with money that nobody had.

By agreeing to go out to Painesville to meet my caller I had opened a Pandora’s box. From individual cancers to polluted water leaking into rivers and Lake Erie, from local school tax funding to state and federal official shortcomings, from the way business capital moves but labor doesn’t.

But I never got to meet my caller. He gave me his name and said he would meet me at a bar in Fairport Harbor the next night. I drove out there, but he did not show up. He had declined to give me his phone number but others at the bar knew him, said he wasn’t well, and they could speak for him. They even produced one of their number who had a perforated septum.

“I’ll show you!” he said, clearly after several Rolling Rocks.

Turning his back he produced a handkerchief from his pocket, pushed it up his right nostril, fiddled with his left nostril for a minute out of my sight and then quickly turned to me with a “ta-da!” and arms held aloft. He had the handkerchief through his perforated septum alright.

He was a younger man than my caller, perhaps in his late 30s and, I would soon find out, was one of hundreds of former chromate workers with the cancer. Chromate is a chemical used to coat metal to prevent corrosion and to enable paint to adhere to it. It’s most popularly known on car fenders but often caused lung cancer when inhaled.

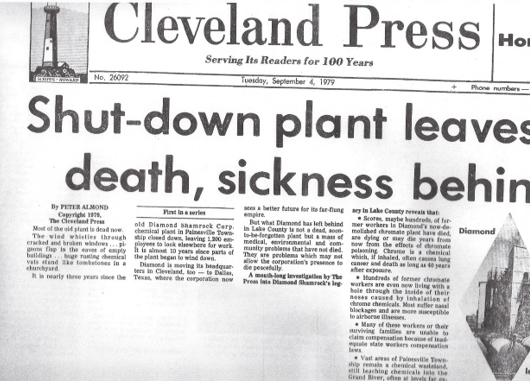

It took me six weeks to research this story, pulling together the plant’s history, its workforce, and the environmental, medical and local legacy. It came together as a 10-part series – 16 stories in all – which began with a front page splash on Tuesday, Sept 4, 1979.

“Shut-down plant leaves death, sickness behind” was the headline, copyrighted by The Cleveland Press.

Here’s the lede:

“Most of the plant is dead now. The wind whistles through cracked and broken windows… pigeons flap in the eaves of empty buildings… huge rusting chemical vats stand like tombstones in a churchyard.

“It is nearly three years since the old Diamond Shamrock Corp. chemical plant in Painesville Township closed, leaving 1,200 employees to look elsewhere for work. It is almost 10 years since parts of the plant began to wind down. Diamond is moving its headquarters in Cleveland, too – to Dallas, Texas, where the corporation now sees a better future for its far-flung empire.

“But what Diamond has left behind in Lake County is not a dead, soon-to-be-forgotten plant but a mass of medical, environmental and community problems that have not died. They are problems which may not allow the corporation’s presence to die peacefully.

“Scores, maybe hundreds, of former workers in Diamond’s now-demolished chromate plant have died, are dying or may die years from now from the effects of chromate poisoning. Chrome is a chemical which, if inhaled, often causes lung cancer and death as long as 40 years after exposure.

“Hundreds of former chromate workers are even now living with a hole through the inside of their noses caused by inhalation of chrome chemicals. Most suffer nasal blockages and are more susceptible to airborne illnesses.

“Many of these workers or their surviving families are unable to claim compensation because of inadequate state workers compensation laws.

“Vast areas of Painesville Township remain a chemical wasteland, still leaching chemicals into the Grand River, often at levels far exceeding state and federal EPA violation limits.

“A dump of chemicals, including highly toxic chromate, has eaten through two feet of supposedly-protective blue clay and a top layer of soil and killed the grass on the site of one abandoned operation.

“Nearly eight years after the chrome plant was destroyed, the chemical appears to have entered the Grand River. The latest river data collected by the state Environmental Protection Agency has disturbed officials enough to consider further investigation.

“The Fairport school district lost 60% of its funds when the Diamond plant shut down. Despite an emergency tax levy, it is still struggling to make ends meet.

“Many former employees, whose average age when the plant closed was about 52 – too old to feel like starting anew, too young to retire – are bitter about the plant closing and Diamond’s decision to move its headquarters out of Cleveland. They feel abused and abandoned, although nearly all who were looking have found new jobs.

“The Diamond Shamrock case raises serious questions about corporate and state responsibility and worries increasing numbers of state and national leaders about the effects of mergers and plant closings on local communities.

The Diamond story began in 1910 when a small group of Pittsburgh businessmen saw a shortage of soda ash for the glass-making industry as an opportunity to build a soda-making plant. They incorporated the Diamond Alkali Co, and located a seemingly-inexhaustible supply of salt 2,000 feet underground in Painesville Township, with close access to Lake Erie, road and rail transportation of limestone and coal, and an abundant labor supply.

As with Cleveland, the people of the area’s local town, Fairport Harbor, were mostly first and second-generation immigrant – Finns, Slovaks, Slovenes and a few Hungarians. The laboring work at Diamond Alkali was hard and accident-prone, but that was the nature of much of America’s raw industry at the time.

One of the most memorable accidents, former union president Steve Adams told me, occurred in 1938 when a worker called Charles Knaph fell into a vat of caustic acid. Only the man’s shirt buttons and belt buckle were recovered. World War II saw a huge boom in chemicals for ammunition. The workers were exempt from the draft – almost unfireable – and, like management, sloppy about procedures.

The US Navy took a direct interest in the plant, but kept a physical distance. “The workers got a raise in wages if they could prove an increase in productivity,” Adams told me. “The figures looked good and they got their pay raises. But the navy paid for tonnage they never got. When they came to the plant to check you know what they found? There’s a three-way cock in the center of the main pipe. The men had turned that cock so the chromate went straight into the river instead of into production!”

In fact, the Diamond Shamrock management (Diamond Alkali had merged with Texas-based Shamrock Oil and Gas years before) appeared to have a case when they told me some of the medical and environmenal problems were the fault of the workers themselves – for failing to wear masks or taking other safety requirements. Many smoked like chimneys.

“Prove it” management said when workers claimed their injuries were the company’s fault. They had a point.

But old federal Environmental Protection Agency files contained the name of one Dr Thomas Mancuso, chief of the industrial hygiene division of the Ohio Department of Health, who had made an independent study of lung cancer deaths in Lake County in 1949, which he updated in 1975.

The study found people who worked at the Diamond Shamrock chromate plant in Painesville Township were 15 to 29 times more likely to die of lung cancer than the county’s general population; that 63% of all chromate workers he examined suffered a perforated septum; 87% suffered chronic rhinitis (severe inflammation of the center wall of the nose). And that they were contracting and dying of lung cancer many years after the cut-off date for Ohio state workers compensation.

Dr Mancuso’s reports had never been published in the media. Previously, Ohio state officials had recorded only 41 workers compensation cases for chromate lung cancer from the Diamond plant from 1948 to 1977. Dr Mancuso, one of America’s foremost experts on chromate poisoning, said this was almost certainly a conservative estimate because most workers did not die in their home town. Most died in places like the Cleveland Clinic or in other places around the country where they had retired.

“Despite recent improvement, Ohio’s workers compensation laws are still out of step with the rest of the nation,” said Robert Sweeney, Cuyahoga County Commissioner and a prominent workers compensation lawyer. James Kendis, another lawyer who had been involved in cases against Diamond Shamrock, added: “The laws need to be completely revamped. They are still a long way behind advances in medical science”.

I did what I did in school desegregation, and looked outside of Ohio to see what other states were doing – and found that New Jersey paid its chromate workers at its South Kerney Diamond Shamrock plant an average of $1,500 for every perforated septum. The company had no choice but to pay it under state laws established in the 1950s Union leaders in Ohio tried, but failed, to get the same kind of compensation.

Almost no publicity, no pressure get the laws changed. State Representative J. Leonard Camera, Democrat from Lorain who was chairman of the House Commerce and Labor Committee and was supposed to oversee workers compensation, said he was almost totally unaware of the problem. “I don’t know everything,” he said. “These things are hitting me now. A lot of people just didn’t know. I’m a pipe worker, and I’ve watched pipe-workers die and not connected it until now with asbestos….. Unless someone brings it to your attention things aren’t always done.”

I did turn the whole of the fourth part of the series over to Diamond’s defence, with officials saying the workers themselves shared the blame. Dr Richard McBurney, director of health and environmental affairs for Diamond Shamrock, who was also a Lake County coroner, was fully aware of the damage the chemical does. He had treated workers, operated on them – and disagreed with very little of Mancuso’s 1949 and 1975 studies.

“It is apparent, however, that he and Mancuso are long-time antagonists and strongly disagree about the company’s responsibilities.” I wrote.

When it came to how much the company’s vast ‘soup ponds’ – chemical settling basins – were contributing to pollution in Painesville’s Grand River my investigation got into a whole barrel of conflicting data. Ohio EPA were worried about increasing nontoxic chlorides leaching into the river. A John Carroll University biologist hired by Diamond Shamrock who examined the river in 1977 said a ‘great diversity’ of fish had returned to the river and shown little evidence of being chemically contaminated. Then that was challenged…. etc

The EPA’s figures for average 1979 levels of dissolved solids were 3,840 milligrams per liter per day at a time when the violation level was 1500 mg. I reported ‘slugs’ of chemicals with all kinds of figures coming down the river; sent off my own soil samples from the ponds for analysis at an independent firm that Press reporter Norman Mlachek had arranged in 1962. Not much change since then: 50% calcium, 10% iron; 5% silicon and less than 1% each of sodium, aluminum and magnesium. The rest was dirt.

And air pollution? That too. C. Lee Mantle, who had one of the largest fruit orchards in the area, lost over 100 acres of apple and peach when the magnesium plant defoliated the trees during WWII. If it wasn’t the boilers, it was the coke plant. If it wasn’t the coke plant it was the cement plant. Etc etc. The Press ran it all.

Yet Diamond Shamrock got away with it because it was the area’s largest employer. “Diamond always was a sacred cow in Lake County,” Fred Skok, former lake County prosecutor and at the time a judge, told me. “They were like a father figure to a lot of people here.” He admitted that a pollution prosecution he had convened 20 years earlier to look at another company declined to look at Diamond because “The Republicans said I would be tilting at windmills. The Democrats said I would upset the company and make them move away.”

Well, Diamond did move away; first to Texas where it had already merged with Shamrock Oil, creating a different sort of corporation with international aspirations, replacing its Painesville operations for Venezuela, where labor costs were much lower. In 1978 there were about 2,000 business mergers across the nation, 80 of which accounted for two-thirds of the total value of $34 billion, the highest value in ten years.

My last big spread that year was all about plant-closing legislation, particularly with the recent closing of the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Campbell Works creating a furore. Hearings on a proposed Community Readjustment Act were due to start in the Ohio Senate in a few days time. As you might expect, industry was opposed. “It’s a restraint of trade,” said Bill Costello, director of government affairs for the Ohio Manufacturers Association. “Our people have stockholders they have to answer to…. It’s the most damaging piece of legislation ever concocted to keep industry out of the state.”

And so, as America – and the world – started to slip into the most severe economic recession since the end of World War II, political battle was joined.

“Today, the accelerating growth of very large conglomerate enterprises through merger represents a radical acceleration of our economic and political landscape,” I quoted Michael Pertschuk, chairman of the federal Trade Commission, addressing a meeting of investigative reporters in Boston. “Yet the implications remain largely unreported.”

Well, I and the Cleveland Press are trying, Michael. I can’t think of any major subject given this all-consuming, huge amount of space in any daily newspaper. Starting with an old man with a hole in his nose and dying of cancer calling up with the complaint “Nobody’s been by.’

I doubt more than a handful of people read every word of the ‘Diamond legacy’ or even a third of it. But it did have an impact. A week later State Senator Tim McCormack, Painesville’s state representative, co-sponsored a new bill to make companies who leave waste dumps around pay for clean-up themselves, or then for the state to do it. We ran two letters from readers (only two?), both from Cleveland Heights, saying well done and ‘why wasn’t this done years ago.’

A year later the U.S Environmental Protection Agency started action on the site, beginning with a clay cap over 120 acres of the worst part of the ‘Soup Ponds.’ But it took another ten years before the Ohio EPA began enforcement of its laws – held up all that time in litigation between several parties. And not until November, 2005, did the Ohio EPA declare that 41 acres of the Diamond site was a ‘substantial threat to public health and safety,’ opening up state funds for remediation.

Then a company called Hemisphere, based in Bedford – a Cleveland suburb – pulled the Ohio EPA, Lake Metroparks and others to a new strategic plan which it called Lakeview Bluffs, a sports-oriented resort community planned to have an 18-hole championship golf course, boutique hotel and spa, first-class athletic fields and facilities, a fly-fishing club, vineyard and winery, extensive walking and biking trails, a marina, amphitheater, private beach, etc. We’ll see.

Actually, the story of chromate poisoning was not just historical. It was current, as a phone call I received from a current worker at another, active, plant confirmed. The company was Metals Applied, at 2800 E.33rd St. in Cleveland, one of at least 30 chrome-plating facilities in the area. My caller said he could prove the ventilating system had not been working properly for many months, and that several employees including himself had perforated septums.

Calls to the plant drew a blank. I would not be allowed to inspect the facilities myself. But my caller said he could get me in. Midnight, by the back door. He had arranged it with the night security guard that he would take a 15-minute break while we sneaked in. He handed me a mask and we went up some stairs to look down at a chrome-plating bath where a section of aircraft landing gear was being treated. A large ventilation tube was positioned above it but it was not functioning. My caller showed me the switch and said it had worked only sporadically for many months.

He had started getting nose bleeds three weeks after starting to work at the plant, and was one of three men he knew with the problem there.

The company showed me records saying that OSHA, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration, had inspected the plant the previous year at the request of a worker who complained of the fumes, but no citations were issued. The chief officer at Metals Applied, Pablo Prieto, told me he did not know of any of the 100 staff who had a perforated septum, and none had complained to him.

Cue a second copyrighted series, blasting out on the morning after Christmas Day, 1979. “Acid fumes imperil workers, U.S. 0K’s E. Side plant here” screamed our front page headline.

The next day it was OSHA’s turn to be accused of failing to adopt recommended changes on violation standards of chromic acid fumes – changes that would have resulted in Metals Applied being ordered to improve ventilation systems the year before. OSHA knew the company had problems. It visited the company in 1974, 77 and 78, citing the company for failing to keep records of occupational injuries and illnesses. It was fined $350 for not properly separating a chromic acid tank from a cyanide tank, which could have been fatal, but the company appealed and the fines were reduced to $50.

Part of the problem was that when OSHA was created in 1970 it legalized the threshold violation standards for almost all of the 28,000 toxic chemicals in use across the country, using out of date standards. They were only ever a guide, but OSHA made them a law. OSHA’s spokesman in Washington said their hands were tied because it was very difficult to change standards. When they tried they were often taken to court by companies. One of the rare times it was done was with the much-publicized problems of polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a killer chemical used in rubber and plastics.

“Much publicized.” There. Those two words again. Why does it take newspapers to dredge up health and safety stuff that should be bread and butter for government regulators?

Cleveland, I found out, had 41% of all the industries listed in the 1980 Ohio Industrial Directory, but only 23% of Ohio’s OSHA staff. Why? Because workers in Cleveland complained less about health and safety than workers in other Ohio cities. Cincinnati had more OSHA staff but almost half the number of manufacturing industries. Toledo had more staff but only a third of the industries of the Cleveland area.

“Congress decided we should concentrate on responding to complaints,” said Ken Yotz, acting director of the Cleveland OSHA office. “After we’ve looked at them we try to move on. Like other offices we have a backlog of complaints. Still, we just don’t get that many complaints here compared to the number of industries. We’re staffed accordingly.”

So, it’s the workers’ own fault 10,000 Ohioans died of occupational illnesses every year?

The Ohio AFL-CIO was stung by that and, a few days later, and for the first time in its history, started seriously to educate workers about occupational illnesses. It secured a $250,000 federal grant, with the help of Ohio State University, to train 175 trade unionists to take a much closer examination of health and safety issues in industrial plants just after I started to write the Diamond Shamrock story.

Coincidence? We did have an impact, I’m sure. On January 2 ’80 The Press’ lead editorial brought both series – Diamond Shamrock and Metals Applied – together to demand that legislators apply lessons both old and new to bring occupational health and safety into the modern world.

OSHA did quickly appoint a new full-time director to its Cleveland office and set about hiring more compliance officers. Two Ohio workers compensation laws were changed as a result of the series. A number of journalism awards from those investigations, both local and national, today help to fill up a wall in my office.

So, that was it for the whole of 1979?

Hardly, though disaster, pain, death and disruption seemed to mark the year in various ways across the world. In March a movie, The China Syndrome, starring Jack Lemmon, Michael Douglas and Jane Fonda, came out in cinemas across the US, scaring a lot of people about the dangers of nuclear power generation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bIGH1AfIS18

Twelve days later, the Three-Mile Island nuclear reactor No 2, near Harrisburg Pennsylvania, made those fears real when it had a partial meltdown. It was a wake-up call for power generation, and galvanized anti-nuclear activists.

US inflation was running at 11.2%. The Soviets invaded Afghanistan in December; 11 fans were killed at a WHO rock concert in Cincinnati when 7,000 young people were caught in a crush for unassigned seating. The movie Alien, starring Sigourney Weaver and John Hurt, came out in May, scaring people even more. It was – and still is – regarded as perhaps the scariest movie of all time.

Another movie, Kramer Vs Kramer, starring Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep, featured a couple’s divorce and the effect on their child, depressing people even more. Saddam Hussein took over in Iraq, resulting in war 11 years later; Ayatollah Khomeini took over in Iran, creating the Islamic Republic of Iran and holding 52 Americans hostage for 444 days. . In August, the IRA killed Queen Elizabeth’s cousin Lord Mountbatten and several others with a bomb on a boat in Ireland. The same day 18 British soldiers were killed in an ambush at Warrenpoint, near the Irish border, cementing The Troubles for the next decade under Britain’s new prime minister, Margaret Thatcher.

Was there no relief?

Well, you could buy the new Sony Walkman for $200 ($700 in 2022 money); Black and Decker’s hand-held Dustbuster, a spinoff from NASA’s moon project, was introduced in January. Monty Python’s movie The Life of Brian came out: the made-up story of a young, Not Jesus next door neighbour of the actual Jesus – in my book one of the funniest films ever, but banned in lots of places, including parts of America.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DBbuUWw30N8

Superman, the movie, starring Christopher Reeve, was going great at the cinema; and Voyager 1 had just passed Jupiter, carrying its little golden record of the wonders of Earth and its humans.

Ah, dreams…….

Memory flash: South Euclid. January 1979

I’m at home watching TV reports of a shooting at a school in San Diego. A 16-year-old girl, Brenda Spencer, has shot and killed the principal and a custodian with a .22 rifle from her bedroom window opposite the school, the Grover Cleveland Elementary School. She has also injured eight children and a police officer. Her father gave her the gun, with a telescopic sight and 500 rounds of ammunition, as a Christmas present.

Asked by a reporter who managed to call her at home why she did it, she said: “I don’t like Mondays. This livens up the day.”

Some time later Irish singer Bob Geldorf, of the Boomtown Rats group, picked up the phrase and co-wrote and performed the song “I don’t like Mondays’ which became an even bigger hit when he sang it at the Live-Aid concert in 1986. Spencer was still in jail in 2021.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FcZW0GFLSdw

There’s no reason, of course, to connect a school shooting in San Diego with Cleveland just because the school’s name has the name Cleveland in its title. Except that, to me, it was the sort of thing that could happen in Cleveland, Ohio. Who would have thought, for instance, that Cleveland would host a World Series of Rock concert at the 90,000-seat Municipal stadium every year from 1974 to 1980, knowing that there is always trouble.

The penultimate show, featuring the band Aerosmith, on July 28, 1979, was about the worst, with five shootings (one fatal), rioting in the streets around the stadium, and massive use of drugs and alcohol.

For much of the year, 1979 was about economics and the gathering storms of depression. Union-management bargaining became increasingly bitter.

“Labor will be seeking to protect its members from the ravages of 9% a year national inflation – 11.2% in the Cleveland area – and demand more fringe benefits, such as better pensions and hospitalization coverage, more time off, even auto insurance.” I wrote.

“Management, however, can be expected to insist that wage boosts, cost of living increases or fringe benefits must be tied to increases in productivity. Businessmen, backed by the federal government, will point to the Carter Administration’s guidelines of a maximum 7% a year wage increases and strongly resist Labor’s demands for more.”

A long analysis of piles of statistics concluded with a quote from ‘Nels’ Nelson, an associate professor of labor economics at Cleveland State University: “All the signs are there for an absolutely horrible year.”

In Cleveland it came down to what the Teamsters and the United Auto Workers would do. First up were the big Teamsters contracts, already in negotiations via the federal government and due for conclusion at the end of March. The United Auto Workers Union would be later and take their cue from the Teamsters. I’d spent time with Jackie Presser and the Teamsters last year, so I focussed more this year this on the 75,000 auto workers and, in mid-April went up to Detroit for their annual bargaining conference.

That produced a nice little expose of Cleveland politics under Mayor Dennis Kucinich, namely Kucinich’s right-hand man Bob Weissman. Bespectacled, withdrawn, conservatively-dressed – including a neck-tie that none of the back-slapping union delegates wore – he looked quite out of place. But Sherwood ‘Bob’ Weissman, personnel director for the City of Cleveland and Mayor’s Kucinich’s closest political adviser, had been a UAW member for 20 years, was a four term past president of the union, and was now a delegate to Local 122 at the Twinsburg Chrysler plant.

It was Weissman who had been key to linking the UAW with Kucinich. Or, WAS the key, for it was clear that UAW President Douglas Fraser and Region 2 (northeast Ohio) director Bill Casstevens no longer needed him. “I talk directly with Kucinich, not through Weissman,” Casstevens told me. “It’s his (Kucinich’s) political viewpoint, not his personality, that encourages us to support him,” added Fraser, who added that Weissman is “not the most well-liked person;” Weissman being brash, antagonistic – and once angrily called a Communist by Walter Reuther, legendary former president of the UAW.

The UAW, a strong supporter of Senator Edward Kennedy and his national health proposals, remained out front of other unions in supporting Kucinich’s battles with businessmen and his pending bid for a seat in the US Congress.

With high inflation the public was feeling ripped off. I offered my own personal example in the front page Column One slot, being ripped off by a locksmith who had attended my front door and handed Anna a bill for $55 – for half an hour’s work, just for labor.

FIFTY-FIVE DOLLARS!

“Now, I don’t know about you, but the only people I know who make $110 an hour are a couple of lawyers and maybe a dentist or doctor or two,” I wrote. Certainly not a 19 or 20-year-old lad probably trained by his locksmith father.

“But that’s the way it seems to go these days.” And so on and on.

I made my point at the end, saying that there are consumer laws to protect us from shoddy workmanship and rip-off artists, but only the laws of raw competition to protect us from a repairman’s exorbitant charges. “The $55-for-half-an-hour locksmith knows he can get away with it because few of us know what he really should be charging” I wrote. Unless we all decide to call a halt and start hollering and complaining.

“Because if we don’t it will get worse. In this increasingly technical world, believe me, it will get worse.”

Declining enrollments dragged me back for another blast about schools on the same page. “It’s 1958 again for Cuyahoga County schools. That’s the level to which enrollment in the county’s public schools has fallen after a decade of decline, according to a report by the Governmental Research Institute. The report shows the enrolment of 248,503 students last fall was just below the 253,000 pupils recorded in the fall of 1958. Enrollment reached its peak in 1969 with 333,000 students.”

In April United Airlines pleaded for passengers to let them know that they are not going to use their reserved seats because of a strike by 18,000 members of the ground crews that was causing cancellation of 60% of United flights from Cleveland. One flight to San Francisco departed the day before with 44 of its 140 seats empty. On the other hand 24 local trucking firms settled their strike- a lockout with Teamsters Local 407 – but only tentatively.

In June a feature on the money page told about a shortage of officers to crew cargo ships on the Great Lakes. “Allure of lakes not so great” is the headline.

“The good money is still there, but life-styles apparently have changed so much that few young men want to be ships officers, particularly on the Great Lakes. Things have actually become so bad that a recent study by the US Commerce Department’s Maritime Administration reveals that if a trend in shortage of deck and engineering officers continues, entire segments of the Great lakes fleet may not be able to sail.”

“If this occurs, there will be major disruptions in the movements of iron ore, coal, limestone and grain,” concludes the Maritime Administration’s study. “This would cause mines, steel companies, automobile plants, power companies and other industries to curtail production and substantially increase unemployment.”

Nothing like a good scare story to focus attention, eh?

Much of the problem, it seemed, was the ships’ image and land-based competition. “I think any one of us prefers the idea of going foreign,” said retired Admiral Paul Trimble, president of the Lake Carriers Assn. “Today it doesn’t sound so good to sail from Gary (Indiana) to Cleveland, when you could be saying you’ve just come back from Bora-Bora.”

Long hours, little vacation and confined to a ship are main reasons. And because a lot of young people just don’t know about the opportunities, what with new and better ships, and continual improvements to pay and conditions.

Memory Flash: South Euclid, July 1979

Anna and I are lying in bed – at attention. It is 6am and our eyes and ears are fully awake and alive to new noises. As is our dog, Douglas, who is sniffing at the bottom of the door of a neighboring bedroom. There, indeed, is a faint gurgling noise coming from inside.

What do we do? When I first heard it I thought it could be a burglar, and was about to call the police.

But then I looked towards my wife. She turned her head towards me on the pillow – and we both grinned: big, happy grins.

WE ARE PARENTS! That noise can only be our new son, just six months old and brought home yesterday from Children’s Services in downtown Cleveland! Thank you, Mrs Marjorie Bodenhamer, our brilliant social worker.

Finally, after four or five years of miscarriages and medical interventions, we have adopted a beautiful, handsome little boy we have named Nicholas. Or to be precise Nicholas John (after my father’s middle name) George (after Anna’s father’s middle name) Almond.

We are instant parents to a boy born six months earlier at St Alexis Hospital, Cleveland. An entirely new world has opened for us. Already six months old? Where’s the manual? What to feed him? What does that cry mean? Can I go to the park and throw a ball for him?

As the clock ticked on and we soaked up the gurgles another noise broke the morning silence: the sound of banging. What?! A budding builder – already? We dashed into his room. Arghh! Where is he? His cot was not where we left it. It was on the other side of the bedroom!

We quickly discovered Nicholas was a rocker. Not in the head banging, heavy-metal sense, but a strong lad who liked to rock himself forwards and backwards in his cot. And sometimes that cot could travel a fair distance. When we entered the bedroom first thing every morning we were never quite sure where we would find him!

Blonde haired, hazel eyed, with the most beautiful smile and gentle nature, Nick was, and still is more than 40 years later, a lovely son.

I don’t remember exactly the date Nick came to us, but I doubt it was before July 10, when I see from my yellowing clips that I filled most of the lead page of the adventure/travel section with a story about backpacking. With a new baby in the house I wouldn’t exactly have had my mind fully in gear to be thinking deeply about whether you “should take a poncho (price $1.90 to $28.45) with you on your long distance hike, or Adler’s combination windjacket and rainjacket made of Gortex, ‘a breathable material that is new on the market, for about $70.’“

At least it gave me a chance to remind myself – and the readers – of my first backpacking experience: 1963, when I was 17 and desperately searching for a place to camp overnight outside Berne, Switzerland, and found I was in a rubbish dump when I woke (ah yes, the smell lingers!) My kit was heavy – canvas rucksack, canvas Boy Scout tent, steel frames, wooden poles, huge sleeping bag, plus clothes and cans of food.

“Don’t pack up trouble in your old back pack,” said the headline. “Travel light and smile, smile, smile.”

“The modern backpack,“ I quoted 18-year-old Doug Webb, who sold camping equipment at Adler’s downtown store, “is made of lightweight ‘skins’ of nylon with an aluminum frame. The sleeping bag is made of synthetic fill or lightweight down. Hiking boots are one-piece and waterproof. They put 60% of the pack’s weight on your hips and thighs – your strongest muscles – not on your back and shoulders like the rucksacks.”

There would be plenty of time for all that with Nick as he grew up, but for 1979 to ’82 my main interest would be lightweight baby strollers – and a backpack to put a gurgling kid in.

No paternity breaks in the 70s. Back on the Labor beat in the heat of an August day I wore a helmet and flak jacket for reporting on a strike at Bailey Control Co, Wickliffe, where brick-throwing members of United Auto Workers 1741 were charged down by the police. “25 arrested in Labor Riot,’ was the headline.

Then, a few days later, a completely different subject: The violent IRA death of Lord Mountbatten, along with an old lady and two children, followed by the deaths of 18 British soldiers. They provoked widespread revulsion across the world, including the Cleveland Press, where I made my own feelings known two days later in a Column One piece.

The column started by referring to a recent visit to Cleveland of a 21-year-old IRA supporter called Ciaran Nugent, who came to the city to tell people about ‘being tortured by the British in what he called ‘concentration camps’. He wanted Americans to sympathize with him, condemn the British and know that his resistance in jail was because the British insisted he admit he was a ‘criminal’ instead of being a ‘prisoner of war, a political prisoner.”

“Now I could sympathize with Ciaran Nugent, even though I am British,” I wrote. “I know the British Army and British police methods. I don’t believe all he says, but I do believe he could have been tortured. A Press interview with him last Saturday may well have fomented some pro-IRA thoughts among Clevelanders. But overnight I have lost virtually all the sympathy I had for Ciaran Nugent and his fellow IRA prisoners.’

I told readers about what I found in Northern Ireland in 1976, and about the young Clevelanders at Ryan’s pub in Cleveland Heights, innocently applauding romantic ‘brotherhood’ ballads of the 1920s and laughing at anti-British songs. And no-one saying a word about the one million Ulster Protestants who wanted to remain British, or the crimes Nugent didn’t want to talk about. He was the first to refuse to wear a prison uniform and to wear a blanket instead: The Dirty Protest

“If he did (the crimes) in the name of the ‘Republican Movement’ – the IRA – then Ciaran Nugent is a criminal, the worst kind of criminal, and Americans should think again about support for his kind,” I concluded.

Memory Flash: Washington D.C. Sunday, Nov 11 ’79

As written:

“Tour 37B – The Nation’s Capital.

“This tour takes in many Washington famous national landmarks: The Capitol, Lincoln Memorial, Washington Monument, Smithsonian Institution, Jefferson Memorial, Kennedy Center, The White House, Pentagon, Iwo Jima Marine Corps Memorial, and Georgetown. (Not necessarily in that order.)

“Time: Two and a half to five hours. Annual event. Price $7.50. Refreshments provided. Large, escorted groups only. Participants must be slightly unusual and provide own transportation.’

We are, of course, talking about the Marine Corps Marathon that I said I’d run a year ago. I’ve written a story about it for the Adventure/Travel section as if it was a travel piece: my first marathon – 26 miles and 385 yards that I aimed to complete in three and a half hours. The piece spreads across the front of the adventure/travel section two days later, surrounding a large map showing my route.

A triumph? Let’s say “First half wonderful. Second third tough. Third tenth painfully difficult, right knee almost non-functioning”. As I wrote of the final part in the piece: “Twenty Six miles. WHO PUT THIS HILL HERE? The last 385 yards are up a hill around the Iwo Jima Monument. I swear that’s a runner they’re planting, not a flag. Leg or no leg I’m not going to walk the last half mile. I manage to run to the finish. …. All I want to do is lie down and die.”

Actually, almost all of it WAS a terrific experience, and an amazing way to see the nation’s capital. With roads cleared of traffic, the 6,500 runners started at 9am along Arlington Ridge Rd alongside Arlington Cemetery and are a sea of joyous emotion under a crystal clear sky and perfect 60 deg F. I can pick out Anna, Nick in his stroller, and friends Al and Nancy cheering us on in the crowds, not once but three times at different locations.

Around the Pentagon, past a high school band playing for us, over the Key bridge into Georgetown: Another band, then past the Watergate complex, made famous by that break-in of Democratic Party headquarters in 1972. ‘Hotel guests used to steal anything they could lay their hands on if it had the words ‘Watergate’ on it,’ I wrote. ‘Wonder if they still do?’

“On our right is the Washington Monument, and on our left the White House. Wonder if Jimmy (Carter) is watching. No. Probably not. After all that fuss about him collapsing in a six-mile run he probably dare not show his face before a lot of hot-shot marathoners.”

I conclude that the Capitol really IS on a hill, and the Marines, in their camouflage uniforms, really are good at handing out water. At 17 miles, though, my feet and knees are really beginning to hurt. It is the furthest I have ever run. Now, the East Potomac Park and Tidal Basin are becoming serious threats, even when I try to cheer myself up with memories of Congressman Wilbur Mills famously being stopped by police there with stripper Fanne Fox, who jumped into the pond in an effort to escape.

At 22 miles I’m poleaxed, and stop running. Runners are giving up, and numbers of them are in the Marines field hospital tent. I jog and walk, jog and walk. Everything hurts. I hear a shout: “Hey Cleveland!” Another runner, from Painesville no less, has spotted my Cleveland Revco half marathon T-shirt, but I can’t keep up with him. Over the 14th Street bridge at 24 miles, and the sightseeing part of The Tour has gone. It’s a fight for survival now.

I see Anna, Nick and our friends on the uphill run-in and wave exhaustedly as the Iwo Jima Memorial appears tantalizingly ahead. At four hours and two minutes I reach the finish line and I get my medal. But then disaster. I cannot find my little reception committee anywhere. I search for them here and there in the huge crowd…. for 90 minutes, while they are searching for me. Anna and friends finally find me sitting on the base of the Iwo Jima Memorial, my shoulders wrapped in an emergency silver blanket.

Oh for the invention of the cellphone! Hurry up!

(PS. As you might suspect, this was not my last marathon; the challenge was just too great. The last was London, 19 years later.)

The end of 1979 did not look very good for the Cleveland Press. There were staff cutbacks and people were starting to leave. The editor, Tom Boardman, retired, his place taken on Jan 2 ’80 by associate editor Herb Kamm.

I was getting itchy feet, too. Lunch at Barrister’s with the guys and gals from the newsroom wasn’t a lot of fun any more. I’d like to have gone to our Washington bureau, but not to replace my friend Al. Perhaps its time to take a career break, a journalism fellowship at some university perhaps. It will be 16 years since I started work at the Northern Echo, Darlington, County Durham, England.

I’ll look at that in the New Year, when I’ll be 34.