Main Body

Chapter 8. Cleveland, 1976

Its America’s Bicentennial. Two hundred years, and still going! Hooray! Down with King George III and the British! Up with Freedom, Justice, and the American Way!

What a year. For me it started with the return to federal court of the NAACP and the Cleveland School Board fighting it out over school desegregation, to Columbus to judge Ohio schools’ best Bicentennial essay, to England for a family vacation, to Northern Ireland where Anna was nearly blown up by the IRA, and back to hear The Eagles’ latest and probably most famous record, Hotel California:

With its beginning:

On a dark desert highway, cool wind in my hair

Warm smell of colitas, rising up through the air

Up ahead in the distance, I saw a shimmering light

My head grew heavy and my sight grew dim

I had to stop for the night

There she stood in the doorway;

I heard the mission bell

And I was thinking to myself,

“This could be Heaven or this could be Hell”

And its ending:

You can check-out any time you like,

But you can never leave! “

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FVsbvFkhzY4 (6:40 mins)

Singer/songwriter/drummer Don Henley once described the Hotel California as carrying with it the same connotations of powerful imagery, mystique, etc “that fires the imaginations of people in all corners of the globe… created by the film and music industry….. It’s not set in the Old West, the cowboy thing, you know. It’s more urban this time.

“It’s our bicentennial year, you know, the country is 200 years old, so we figured since we are the Eagles and the Eagle is our national symbol we were obliged to make some kind of little bicentennial statement using California as a microcosm of the whole United States, or the whole world, if you will, and try to wake people up and say “We’ve been okay so far, for 200 years, but we’re gonna have to change if we’re gonna continue to be around.”

Fifty years later it was arguable that nothing, really, had changed, at least as far as American society was concerned. The poor were still poor, the rich got richer, crime was often as bad as ever, the climate was approaching crisis, And racial conflict was still making headlines.

Indeed. BLACK LIVES MATTER, the protest call of the early 2020s, could have been the motto for the Cleveland schools desegregation case, which continued to occupy my full attention when it restarted in federal court in early January, 1976.

At its heart was a 16ft by 12ft aerial map of the city of Cleveland that the NAACP had positioned in the vacant jury box of the court. It showed every school in the system, with each school’s boundary lines for enrollment purposes. Transparent overlays were used by the prosecution lawyers to make their case that boundaries were made to keep this part of the city racially segregated from that part.

Mayor Perk and the City of Cleveland wanted to join the school board in the case, but were fiercely denied by Judge Frank J. Battisti. He was even fiercer with a group of black parents who wanted to be heard separately in the trial. Instead we got the same lawyers questioning and cross-questioning out-of-town experts about their own competence, experience and conclusions. At one point, though, Cleveland’s most famous politician, former mayor Carl Stokes, was on the stand to testify for the NAACP.

I, and sometimes my colleague Bud Weidenthal, spent days and days listening to complex arguments about statistics (“that’s completely out of date” “Oh no it’s not”); geography (“There’s a wide gully between this school and that school, you can’t just walk across it”); legal history (“the Supreme Court ruled in Milliken vs Bradley (Detroit), “Swann vs Charlotte-Mecklenburgh (N. Carolina)” or “Keyes vs school district No 1 (Denver”); and staff employment (“this black community demanded black food, black teachers, black principals” “No, we worked hard to mix white teachers in black schools, and black ones in white schools”).

And so on. In detail. Vast amounts of ink.

Memory flash: Cleveland 1973?)

I’m watching an episode (repeat) of the sci-fi TV series Star Trek, It’s called “Let That be your Last Battlefield’ and is about the spaceship Enterprise being caught in a battle between the last two survivors of a centuries-old war between two human-looking aliens with great destructive powers. The only way to tell them apart is that they are half black and half white: that is, one side of their faces is black and the other side white, the difference being that one is black on the left side, and the other is black on the right side.

No matter that Captain Kirk steps in and tries to calm them down, they are utterly committed to destroying each other. I seem to remember that as the Enterprise flies away they activate a self-destruct system, and then ‘poof’ there are no more black and white aliens at all in their galaxy.

I’m not saying this case is motivated by hate, far from it, but there are powerful emotions about segregation that can, and have, generated anger.

Indeed.

For that emotion in court, we had the experience of Yvonne Flonnoy.

Miss Flonnoy was a 21-year-old black product of Cleveland’s public schools. And for the first time in the trial we heard the details of what it was like to be racially discriminated against. She told of black children being required to put their heads on their desks when white children left the classroom; of being unable to go to the toilet at the same time as a white child, of her teacher giving gold stars to white children on a chart but sticking her gold star on her forehead.

She told of white children being punished by having to stand for five or ten minutes but black children being punished by being struck across the hand with a ruler. And for a whole year at an elementary school she was never allowed to visit other parts of the school, such as the swimming pool, gymnasium or library.

By Jan 23 ’76 the NAACP had finished presenting its case: 300 examples that it said proved that schools were built in black areas rather than mixed ones, by changing district lines in ways that intensified segregation, and by allowing white pupils to transfer out of predominantly black schools.

The Press opined that this was the halfway point in the trial and that “it would not be surprising if many believed the NAACP has just about taken the ball into the end zone.” But that would be a mistake, the School Board now had its turn.

“This newspaper has given the trial intensive coverage, aware as we are of the enormously important social implications,” said The Press’ lead editorial. “We hope readers have been following the trial closely and will continue to do so as it enters its second and final phase.

“Certainly, the proceedings in the trial are not glamorous, and they are often tedious. But a person who has kept abreast of what has been going on in the courtroom will at least understand the reasons behind whatever decision the judge finally makes.”

I’ve highlighted this because 50 years later, as I was preparing to do jury service in England one last time, I was aware and appalled that the public in America, Britain and elsewhere around the globe could no longer receive such detailed court reporting as a routine matter. Of course TV and radio carried bulletins of high-profile cases, and social media could provide the latest short updates, but nothing could replace a willing, experienced, independent organization committed to public service than a properly-funded local newspaper.

The case went on with the School Board presenting its arguments, with its chief witness, of course, being Supt Briggs (his preferred title of ‘Doctor’ was an honorary one, admitted his lead attorney), as the man who had run the schools for the previous 12 years. “Casey is at bat,” was the comment of one NAACP lawyer to their most vigorous grilling of any witness yet in the case.

For the uninitiated, which included me, ‘Casey at bat’ is perhaps the most famous poem in American sports history, written by Ernest Thayer and first published in the San Francisco Examiner in 1888. It is a tale of public hope and confidence in a renowned baseball player who comes to bat at a vital point to save a game in the fictional town of Mudville. But, despite the huge encouragement of the home crowd, Casey’s arrogance and overconfidence are his own undoing:

“Oh, somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright;

the band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light,

and somewhere men are laughing, and somewhere children shout;

but there is no joy in Mudville — mighty Casey has struck out.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3SUEUscZ2QA

Did Casey (Briggs) strike out in his testimony to federal court?

I don’t think he did, not by the prevailing standards of the time, anyway. Neighborhood schools were the first priority of almost every school district in America. The public wanted them – black and white. Parents wanted their children close at hand, where they could easily walk home, where their friends and neighbours lived, where they formed a community of like-minded interests.

Battisti himself insisted that his grilling of Briggs did not indicate he had already made up his mind about the case. “My goodness,” he told the court, “I would have to be devoid of any sensibilities at all to sit here for all this time and not realize this. It is painfully clear that segregation doesn’t equal liability.”

He did not want his comments about white flight and the public’s fears of desegregation to imply “a callousness on the part of the court as to the convictions of the public”.

Briggs told the court that when he became superintendent in 1964 the physical state of Cleveland’s public schools was among the worst in the nation, and his priority was to rebuild them. With strong public support and finance he ensured at least one new school every year.

One new SEGREGATED school, the NAACP retorted. And indeed, even I was aware at my school in England in 1963 that America was changing, as that year Alabama Governor George Wallace “stood at the schoolhouse door” and tried to block the admission of two black children. Against the might of the federal government he lost.

Briggs and others tried every which way to integrate schools by such means as new ‘Magnet Schools’ to attract black and white students to specialist education, events with suburban schools, introducing white teachers into black schools and vice versa. Many black schools were overcrowded. How could he NOT build new schools there?

What was the alternative?

Apart from involving all the suburbs, the only one mentioned in the case was busing, forcibly moving children from one side of the city to the other in the morning and back in the afternoon in order to put black and white together in the classroom. Briggs knew there was very little public appetite for that. He could read the school enrolment figures better than anyone: thousands of white parents – and some black parents – were leaving the city for better housing in the suburbs, meaning city schools were increasingly black or white. And private schools were alternatives for those who could afford them.

But I’m not so sure there wasn’t another way: the reordering of housing, public and private. It had already been shown that the Home Owners Loan Corporation, a product of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal of the 1930s, used maps of cities across the country that color-coded urban areas high risk (unprofitable) and low risk (profitable): in racial terms black and white. Insurance companies used them after World War II to show where urban areas were risky business, or not.

Yet federal agencies such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which had considerable control over where the taxpayers’ money was spent, were not nearly as prominent as defendants as I had expected. Neither were federal courts themselves held responsible for failing to ensure government largesse from the 1930s to the 60s did not result in segregation. And while the Cleveland School Board and the state of Ohio said they couldn’t be blamed for housing patterns – and were not obliged to follow HUD’s policies anyway – they did not do enough on their own to encourage desegregation.

The legal key to the case, both sides agreed, was ‘intent’: ie did the Cleveland schools intend to encourage segregation when they made certain decisions, such as building new schools in segregated areas when they knew it was against federal law? If they did then they were clearly guilty as charged. If they didn’t then they were still guilty if they knew, or should have known, it would result in an increase or perpetuation of racial segregation.

If Judge Battisti did conclude the schools were guilty of intentional segregation, claimed School Board attorney Charles Clarke, it would be the first time in the history of the United States that the neighborhood school concept had been ruled a violation of the US Constitution. The case would then go to appeal, and probably to the US Supreme Court.

Looking beyond a favorable decision, NAACP attorney Nathaniel Jones made one last pitch for the remedy to include full involvement of all the Cleveland suburbs.

By the middle of March the case was concluded and left to Judge Battisti to decide.

I had been watching him and talking to him and to others for months and was fairly sure he would rule against the school board. He was a very intelligent man, who because of his personal background, his legal experience and his interest in humanities and political development would not accept the status quo.

He was tough, bold, liberal, decisive, strict, opinionated – and powerful, because as a federal judge he could not be removed except by congressional impeachment.

A lot of people said he was obviously biased in the way he conducted his interrogations of witnesses. But that did not necessarily reveal the way he would rule on a case. One example was his pressing questioning of an air-traffic controller during a plane-crash case a year earlier. Government lawyers felt sure they had lost the case, yet Battisti ultimately ruled in their favor. He also upset very many people across the nation when he dismissed civil charges against eight National Guardsmen who shot and killed four student Vietnam-war protesters at Kent State University in 1974.

“To paraphrase Winston Churchill,” I once wrote, “Frank J. Battisti is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. If there is anything consistent about him it is contradiction.”

He was born in nearby Youngstown in 1922, the son of an immigrant from a village in northern Italy who became a steel worker in Youngstown. He went to Ohio University in 1941, wanted to be a lawyer but – without telling his mother – joined the army, ending up as a combat engineer who saw action in Normandy and Belgium. He returned to Ohio U, got a degree in political science in two years and graduated from Harvard University after three years.

He started out in private practice in Youngstown in 1956, but found himself unsatisfied with it. He had done some legal work for the local Missionaries of the Sacred Heart and felt he had a calling as a priest. He told one of the Provincials of his desire and asked if he would be expected to continue to do the Order’s legal work. “Yes,” his boss replied. Said Battisti: “He turned to me and said very stiffly, ‘Frank, I think we should end this right here,’ and walked out. I was stunned. But I knew that it was final and I decided to go into public service.”

He ran for Common Pleas Court in Youngstown, lost, and was elected two years later. Through that city’s Congressman, Robert Kirwan, he was appointed to the federal bench by President John F. Kennedy in 1961. Two years later he met and married Gloria Karpinski, who became a national expert on penal reform, served on the Ohio Pardon and Parole Commission, the Cleveland Library Board, and headed the sociology department of Notre Dame College.

Quite a powerful political couple.

It was also no secret to the Cleveland schools case that Battisti was a long-time friend of the NAACP’s chief prosecutor, Nathaniel Jones, who also grew up in Youngstown. They met in the 1950s when both earned a few extra dollars teaching law at Youngstown College. Jones also went on to be a federal judge, together with Battisti becoming known as Youngstown’s most prominent lawyers. A new building completed in the center of the city in 2002 was named as the Frank J. Battisti and Nathaniel R. Jones Federal Building and United States Courthouse. (perhaps it needed to be a big building to get all that into a nameplate!).

I wrote about the Battisti and Jones link deep in the last of a four-column profile of Battisti on March 11. The Sunday Plain Dealer, however, picked it up and made it a feature story three days later, the unspoken suggestion being that ‘the fix was in,’ in favor of the NAACP.

Maybe it was. It had long crossed my mind. But having gone through a few painful racial experiences since I arrived in Cleveland my mind was sensitive to the public damage it could cause if I highlighted it. My editors kept it where it was.

Indeed, the PD’s story was identified in court as the single exception to the media’s ‘excellent’ coverage of the case. NAACP attorney Thomas Atkins referred to it in court as “efforts to intimidate the court itself,” which in turn brought the quick addition from Battisti that this ‘did not serve the public good,’ adding to colleague Bud Weidenthal that “such occurrences outside the courtroom would in no way effect the conduct inside”’.

Otherwise, we, the local newspapers, were awarded high praise by Battisti and Jones. Battisti said: “My feelings about a free press are extremely strong…. And frankly what I have read of the day to day coverage of the trial has been quite fair and well done.” Jones said: “I do feel that the media coverage has been extremely valuable overall. Some of the best I’ve seen. “

“One of the problems we had in Detroit was that the violation phase of the case was not reported.” He told Weidenthal that the extremely strong negative reaction to the busing order in Detroit was at least in part because they (the public) were unaware of the extent of the evidence. “That is not true here,” he said. The School Board’s lawyers saved their comments on the press until after their final arguments.

In hindsight, 50 years later, perhaps I should have made more of the Battisti – Jones connection, because the whole busing thing fell apart anyway after the Millennium. But that was then…

Memory flash: Boston, Mass. April 11 76

I’m on a school bus winding around the streets of this old colonial city. There’s tension in the air.

It is a week after the city made national and international headlines over the ‘flag incident:’ a photograph showing a young white man viciously thrusting a sharpened pole carrying a Stars and Stripes flag at a black lawyer who happened to be passing.

The picture by photographer Stanley Forman, which went on to win a Pulitzer Prize under the caption: ‘The soiling of Old Glory,“ featured the fury of a student called Joseph Rakes, who later said he thought busing would take away half his friends.

The Boston newspapers are carrying stories that tell of millions of dollars wasted by inefficient school bus operators at city hall, and that Mayor Kevin White has appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court asking that the increasingly-difficult schools desegregation order be modified to an ‘acceptable’ level. Cleveland’s Mayor Ralph Perk is the first mayor in the country to join him in his argument.

What I’m finding is ominous for Cleveland if Judge Battisti rules there must be busing.

In Boston, which started busing in 1970, 17,000 children have left the school system in the last two years. My bus ride is taking me from a school in mostly-white Charlestown to mostly black Nathan Hale elementary in Roxbury, a mere four miles via a long tunnel. For the principal at Hale busing is a failure because only four of the 49 white children scheduled to be bused actually arrived that day. The yellow school bus has been cancelled: the four now come by taxi paid by the school board.

There is hope, though, at English High School, one of the oldest in America, which is less volatile and more affluent. Desegregation has gone from 95% black to 45% black, 41% white and 14% Spanish-speaking in the last 20 months. It is a city-wide school that puts on extra buses after school to enable many new activities.

School administrator James Buckley tells me that in the first year of desegregation blacks and whites sat at separate tables in the dining room. “Next year there were more friendships and now you see lots of racial mixing at lunch.”

Student Mark Higginbottom, a black senior, disagrees. He sees little racial mixing, little to keep blacks and whites from fighting.

“Man, the best thing about this school is Friday nights,” he tells me, anticipating weekends at home.

And so on to the Bicentennial summer. I don’t remember much about the Ohio schools essay competition I spent a weekend judging in Columbus, but I do have a copy of the looong piece I was asked to write on my view of America for the Press on Bicentennial eve, July 3, 1976. It started at the top of one page and skipped to the bottom of another. Headline: An Englishman’s view – America is still divided.

I started with the body over the telephone wires I saw outside Cleveland’s central police station on that bitterly cold dawn in January, 1970, and went on through a lot of contradictory adverbs to say, within a couple of hundred words, “This is one of the most difficult journalistic tasks I have ever undertaken. For the answer is, I’m not yet sure I really know.”

The next thousand or more words amplified my uncertainty with examples: what I thought six years ago had changed, and as America had changed so had I. “There have been times when I thought I could say: “Aha! That’s it. That’s what America is all about!” But something else would come along and completely confound it” I wrote.

“Britain is a far more homogenous country. Its national history is long, its culture deeper, its class divisions more rigid. There is such a tremendous gap between a Mexican-American construction worker in Arizona and a Polish-American construction worker in Chicago, both in cultural background and geographic location, that the bond between them is much harder to forge.

“To me that gap helps to explain why national personalities, products, companies and organizations are given so much attention in the media – from movies to TV and radio. Comedians joke about Right Guard, Alka Seltzer, Richard Nixon and Jimmy Cagney, recognized across America whoever you are and wherever you are.” … All this is to say that the fabric of American society is still being woven, and that consequently the IDEA of national unity is much less a reality than it is in England. (This is written nearly 50 years before the United Kingdom sometimes gives an impression of dissolution!)

“It forces into greater prominence the magnificent United States Constitution, and from it a deep respect – even blind adherence – to the written law. That’s not always been easy for me to accept as an Englishman, because there seems to be stronger national consensus in Britain, whereas in America there is wider divergence of attitudes and values.”

There is more in the piece specifically about Cleveland, and three cartoon illustrations (cop giving me a speeding ticket; scribbling into a notebook as buildings burn from rioters; watching Archie Bunker on TV saying ‘Stifle’).’

July 4 itself is a complete blank. I guess Anna and I met friends, ate hot dogs and watched fireworks or marching bands – or both. Or perhaps we had a Big Mac Attack: “Twoallbeefpattiesspecialsaucelettucecheesepicklesonionsonasesame-seed bun.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dK2qBbDn5W0

Memory flash: Lakewood Park, west Cleveland, summer 1976

Walt, Pete, Jerry, Wally and the other guys from the newsroom who make up the Press softball team have kindly let me have a shot or two at America’s summer game, softball.

“Let’s have a little bingo here!” shouts Walt in encouragement as the pitcher lets fly with the fastest underarm pitch I’ve ever seen. It’s a big ball, larger than a baseball, and designed to be hit – for more fun.

“Swing – and a miss,” as every commentator says every time a player strikes out.

Once in a while I did connect with the ball, and off I’d run to first base, even second. Did I ever get all the way round for a score? I can’t remember. But it was fun, I was able to take all the joshing – “Hey, Almond, hold the bat like you do for cricket!” – and I now look at the wooden bat behind my chair with the word ‘Press’ on the handle with considerable nostalgia. (a compound word from the ancient Greek ‘nosta’ meaning ‘Homecoming’ and ‘algos’ meaning ‘pain’ or ache’).

And so to running, at which I was a bit better.

And at the movies I know we had the arrival of Rocky: Sylvester Stallone as the rags-to-riches wannabe boxing champ, with its stirring music and on TV ‘Jiggle TV’ from Charlie’s Angels, starring gorgeous crime fighters Farah Fawcett-Majors, Kate Jackson and Jaclyn Smith.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DhlPAj38rHc

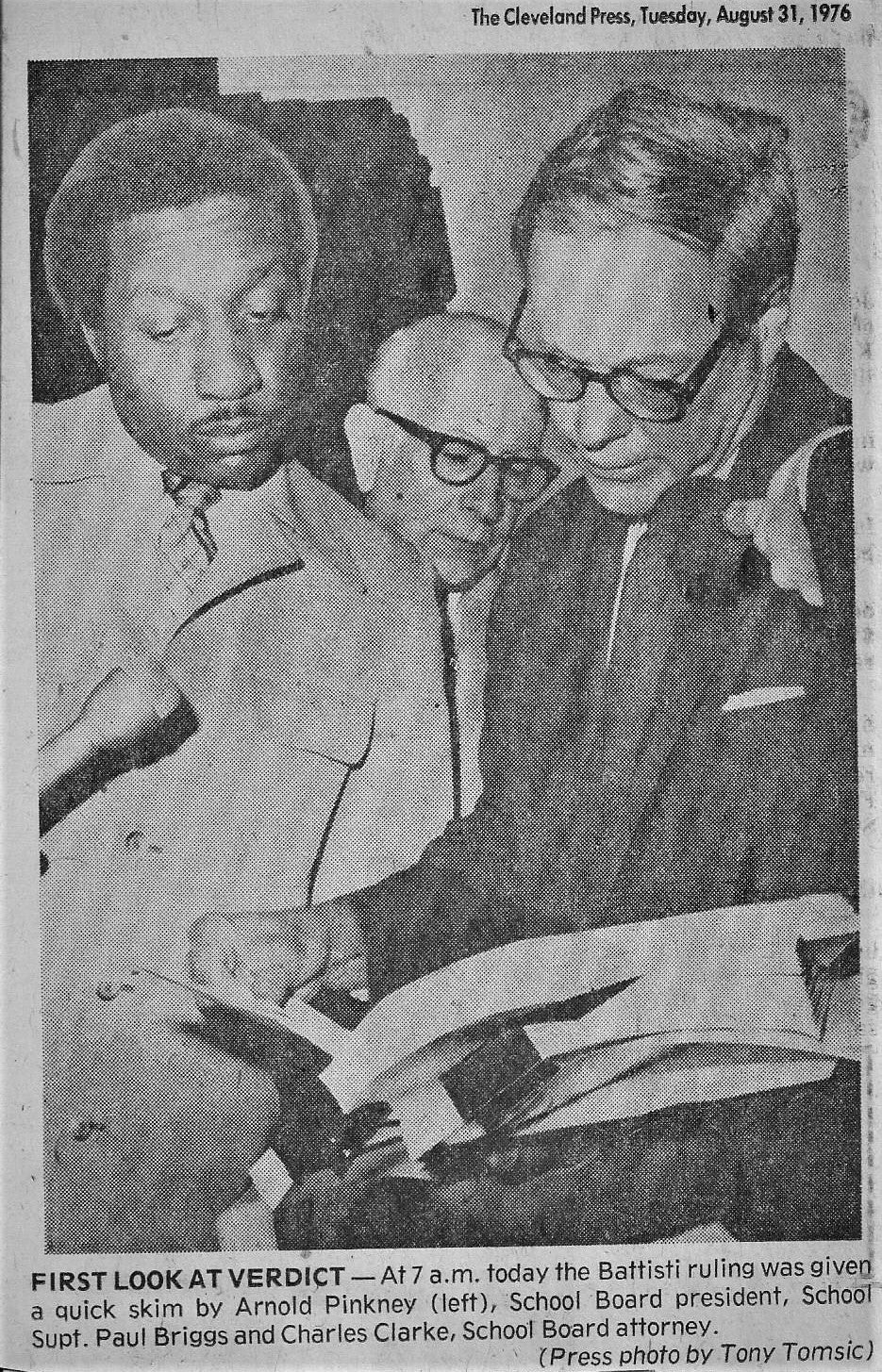

Judge Battisti ruled on the desegregation case on Aug 31. Guilty, as expected.

His 203-page ruling – which came in shopping carts and cost $50 each – made no mention of the kind of remedy to go into effect, but ordered the state and Cleveland school boards to come up with a plan in 90 days, assisted by a court-appointed expert and advisory committee. Battisti found that the majority of segregation examples cited by the NAACP were proven, but was charitable towards the school officials involved, saying they were, in all probability, responding to the social and political pressures of the day.

“Clearly since the 1940s there has been an enormous rethinking as to how public officials should treat racial issues,” he said. “Indeed, this process continues this very moment.”

Well, not strictly the very moment the ruling came off the printing presses. Battisti was already halfway to his ranch in Montana, where he took a long vacation and went fishing.

And so did Anna and I take off – for England and Ireland, – a few days later. We knew it would take time for a full remedy to be worked out, including the inevitable appeal to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals (it took two years) and we needed a break. So we took ourselves back to Blighty for six weeks, the latter two being in Ireland, both South and North….

….…Where we would swap Black vs White American societal conflicts for Catholic vs Protestant in Northern Ireland ones. At the end I gave The Cleveland Press a six-part series at the peak of ‘The Troubles.’

BELFAST, N IRELAND, October 1976.

It was her eyes that have stayed with me: dull, lifeless eyes, sunk into a grim, tired face. The face of a revolutionary, with a flat voice delivering the same lines time after time.

This was Mrs Marie Moore, one of eight members of the council of the Sinn Fein, political wing of the IRA. She was middle-aged, pudgy, simply dressed, with nicotine-stained fingers, and was a life-long Republican and community activist. She had lived in a house in the Clonard area of Belfast where, in 1942, IRA member Tom Williams was arrested for the murder of a police officer because he was one of the minority of Catholics in the Royal Ulster Constabulary. The officer left behind a wife and nine children. Williams was executed.

Mrs Moore was not a killer, but she made no secret of her support for the Irish Republican Army. “I don’t know how the freedom fighters select their targets,” she told me at the IRA’s ‘headquarters’ at the Celtic Bar on the Falls Rd (yes, there was an IRA headquarters – if only an administrative one), “but you must remember we are living in an occupied country.

“The British made heroes out of the French Resistance fighters when they attacked troops and Germans and their French collaborators in World War II. We’re fighting for the same goals as the French Resistance.”

“Every generation has proved that with the British here, there will always be some sort of trouble. If the British went, I don’t think there would be civil war. I think the Protestant people will look at a federal style of government for the whole of Ireland. They would still be in charge of a regional government in the north.”

Mrs Moore was seeing me not because she knew I was British – and certainly not because she knew I had been with the British Army in Germany in 1969 when troops came to Belfast as ‘saviours’ to the Catholics – but because I had travelled here from Cleveland, Ohio, where there were a lot of Irish men and women who support her cause. Indeed, she said she had just returned from a fund-raising trip in the United States.

It was clear to me, though, that she was not quite on the same page as Cleveland’s IRA supporters. There, in my view, they simply wanted a united Ireland, whatever it took. Mrs Moore though, would not accept what the ‘Irish Free State (Eire)’ had to offer at that time: “completely controlled by the Catholic Church, controlled economically by England. We want a socialism that suits Ireland.”

(It is important to note there were/are two IRA’s: the original, older Irish Republican Army was Marxist-Leninist who thought reunification with the South could only come about with peace between Catholics and Protestants, and the newer Provisional IRA (PIRA) which thought unification could only be achieved by attacking British commercial and military interests)

(Marie Moore went on to become secretary to Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams when he won the West Belfast MP seat, served four terms on Belfast City Council, and was heavily involved in support of the Dirty protest of Bobby Sands, the IRA bomber whose handiwork Anna and I would see within hours. She died in 2009, aged 72).

As mentioned previously, it was Anna’s opening of a window at her hotel in suburban Dunmurry – to try to catch an escaped parakeet – that probably saved her from injury when Bobby Sands and five of his PIRA gang blew up a furniture storehouse nearby. Other hotel windows were blown in; hers were intact because she had them open. That incident was the one involving housewife Mrs Agnes Nichols, who was featured in the opening part of my Northern Ireland series on the front page of the Press on November 8, 1976. Headline: ‘It’s not much of a life here anymore.’

They say in Northern Ireland that if you stand still long enough trouble will surely find you. Most people kept moving in those days. To a visitor making their first visit Northern Ireland in 1976 it was an affront to the senses: a profound shock that a part of Europe can officially be at peace and yet be in a permanent state of siege. Every hotel, public house, bank, government building and meeting hall was surrounded by barbed wire and steel drums filled with concrete – to minimize the effects of car bombs.

Fortunately for us, by the time we arrived in early October the record-setting hot weather that had turned Ireland and the UK into mini-Californias for the previous three months had changed to cool and wet, just the kind of weather for appropriately gloomy photos.

We had been amazed at the sight of light brown fields instead of the green hills of home as we made our final descent into Heathrow, and surprised even more when, after visiting families and friends, we arrived by sea into Cork, Irish Republic, and saw the landscape as badly hit by drought as in England.

We started out as tourists, kissing the Blarney Stone, driving around the Ring of Kerry in the south west, to Galway Bay, to the fabulous Ballylickey country house where we fell in love with the owner’s two Labradors, and back to Cork. A history lesson of the 800 years of England and Ireland’s fractious relationship. You can take it back further, to St Patrick, who came to Ireland from England in 461 AD as a Romano-British missionary to convert Irish heathens to Christianity at about the same time as heathen Angles, Saxons and Jutes were converting most of the Christian English to heathens.

This helps, perhaps, to explain the ancient strength of Catholicism in Ireland while England’ s Henry VIII rejected the Pope in 1530 and sent Protestants from Scotland and England to take land away from the Irish in the north. The scene was set for a series of rebellions that was hardly settled by the Irish Republic becoming an independent free state in 1921.

But the further south you were from Ulster the less concerned about The Troubles the Irish appeared to be. In Cork, for instance and perhaps surprisingly, I found many southern Irish sympathetic with the Protestant rejection of union with them.

“Why should they (Ulsterman and women) join with us? They have a better deal as part of Britain”, one trade unionist told me. A shopkeeper even thought the 1916 Easter Uprising ‘might have been a mistake. I mean, how much better off are we after 50 years? The British government has on the whole been pretty decent to the working man, compared to our government.”

Oh dear, how’s this going to go down in Cleveland’s Irishtown bend on St Paddy’s day?

We headed north along slow bumpy country roads through towns and villages looking much as they did in Victorian England. Crossing the border into Northern Ireland, however, showed the gap between the countries – literally, as the roads into Crossmaglen were much better paved. We had chosen this route because this area of Armagh was renowned for its Republican statue, its 97% Catholic population and for the big, heavily fortified British Army garrison. At least 58 police officers and 128 British soldiers were killed by the Provisional IRA in South Armagh during the Troubles. Not surprisingly, it was known as ‘Bandit Country.”

Two days later, in Belfast, I joined the 2nd Battalion of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers on patrol in the western section of the city. I wore a helmet and flak jacket and found out the young soldiers have to be well trained to put up with a lot of abuse. No Catholic, it seems, is ever going to forget ‘Bloody Sunday’ the January day in 1972 when men from the Parachute Regiment shot and killed 26 civilians during a protest march in Derry.

I went out with two four-man patrols who walked out of ugly Fort Monagh and patrolled the streets of Andersonstown. They cradled semi-automatic rifles in their arms but were required to act like policemen, talking to residents and even trying a joke or two. They stopped taxis and vans, asking for names, addresses and the contents of their vehicles before sending them on their way. A “surly and suspicious youth”, I wrote, was frisked and mouthed obscenities at the soldiers who said nothing and walked away.

The soldiers knew their enemy was the hidden booby trap, squads of boys who could accurately put a stone between their eyes from 200 feet, and over the same distance could burst a bottle against a lamppost over their heads. The KOSB soldiers were given five weeks training in a ‘tin city’ in Germany that looked like a Belfast street, where they learned to take insults from young female soldiers posing as Catholic girls.

You never knew where and when there was danger – as I found out when I phoned Anna that lunchtime to say I was OK, nothing was happening. Her response: “What? What’s going on? There’s soldiers running around. A huge bang. We’ve had to get out of the hotel!”

Flak jacket, helmet and personal armed guard or not, it was not me who was in danger, it was her in her hotel room.

We had already stayed overnight in Ballymena, County Antrim, where the newspaper headlines were screaming; “Ballymena in bombing blitz” as 14 bombs had exploded in its shops, killing one and injuring four. Up to then the town that was home to Protestant leader and firebrand the Rev Ian Paisley, had been relatively peaceful. Anna took notes of her own, showing that the woman who died was a 26-year-old Protestant mother of three who was trapped by flames at the rear of a shop. The four men seriously injured – and being a nurse she noted their serious injuries – were some of the bombers, whose own bomb exploded prematurely as they primed it in a car.

“Later that night,” she wrote, a gang of drunks murdered a 40-year-old Catholic wino who was beaten and set afire in retaliation for the woman’s murder.”

Put Mrs A on the payroll, Cleveland Press! Who needs me when you could have someone who can do a lot more than patch up a paper cut?

I did ask the colonel in charge of the KOSB’s if this was Britain’s Vietnam. Will the troops become demoralized and refuse to fight, as some American troops did in Vietnam?

“No,” was the colonel’s answer. “I’m convinced it couldn’t happen to us. The British Army is all-volunteer, unlike the U.S. Army in Vietnam. Every army unit knows it will be in Northern Ireland sooner or later. And every soldier knows that from the start. He’s heard enough stories to know what it’s like here.

“Second: if a soldier wants out, he can buy himself out. He can come to me on a Saturday, plunk eighty pounds on my desk, sign a couple of forms, and that’s it. He’s out of the army. It’s a terrific safety valve. In the 16 months we have been in Northern Ireland a total of 36 soldiers have bought themselves out.”

Was there any light at the end of this dark tunnel?

Maybe one: the Women’s Peace Movement, which had already encouraged many thousands of people – mostly women – to march for peace in Belfast, Londonderry, Cork, London, Stockholm, Glasgow, Toronto and Paris, brought together by one single ‘enough is enough’ moment.

That was the day in August that IRA fugitive Danny Lennon, just released from three years in prison, was chased in a speeding car by British troops who had seen him and accomplice John Chillingworth transporting an Armalite rifle through the main shopping area of Andersonstown. Resident Betty Williams swears she saw the rifle being fired at the soldiers. The troops fired at the car, killing Lennon instantly and seriously wounding Chillingworth.

The car went out of control, mounted the sidewalk, and killed three of the children of their mother, Anne Maguire, who was seriously injured.

Mrs Williams immediately started a petition of mothers, both Catholic and Protestant, 200 of whom marched through Belfast demanding an end to the violence. Ten thousand people attended the emotion-filled funeral of the three children, where Mrs Williams first met Mairead Corrigan, sister of Anne Maguire. From this the ‘Peace People’ movement was born, with spontaneous marches held throughout the island. They attracted media attention from across the world, helped by Irish journalist Ciaran McKeown, an avowed pacifist, who had his own agenda of creating a new type of community, neither Catholic or Protestant, or British or Irish.

“I’m Catholic,” Miss Corrigan told me as we travelled together that evening to a peace rally at Carrickfergus Town Hall, “but I don’t think of myself as Southern Irish, and I’m certainly not British. I’m Northern Irish.”

But it was clear their conventional, middle-class, middle-aged audience were not sure where the Movement was going. One man sought reassurance that there wasn’t a split in the movement. “I would prefer that you not be reassured,” responded McKeown. “You should be frightened. You should be frightened that this whole movement will fall apart. Because there is nothing else,”

I concurred, at the time. “The Peace Movement is the only organization widely accepted by both Protestants and Catholics,” I wrote in the penultimate article of the series. “So far the politicians have kept out of it. There is an outside chance the movement may succeed.”

Williams and Corrigan were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize the next year. But that prize money, in itself, split the two women: Corrigan wanting to spend her half on local campaigns, Williams for keeping hers and spending it on more global peace problems. The split soured even more in 1978, and by 1980 the Peace People movement was essentially dead.

1980 was the year that year Anne Maguire, unable to get over the loss of her children, committed suicide. Her widowed husband, Jackie, himself a significant peace campaigner, married Anne’s sister, who became known as Mairead Maguire. Betty Corrigan engaged in many overseas peace projects, moved to the U.S, married an American businessman, moved back to Galway in 2004 and died in March 2020.

It was not until 1998 that the Good Friday Agreement ended most of the violence in N. Ireland

My series ran in The Press in November, 1976, over six days, and I’m glad I did it when I did it: at the peak of The Troubles (apart from nearly getting my wife blown up, of course!). I’m even more satisfied that my editors thought so too. At the conclusion of the series the paper’s lead editorial was headlined Northern Ireland’s lesson over three columns above the masthead. It reflected exactly my thoughts as Cleveland prepared for perhaps the biggest sociological change in its history – that of court-ordered school desegregation.

Is Black vs white in Cleveland going to be as bad Catholic vs Protestant in Northern Ireland?

“The divisions between the races here may be just as deep as the divisions in Northern Ireland,” said the editorial. “Poised as Greater Cleveland is on the edge of one of America’s greatest social problems – school desegregation – we should all clearly note what happens when two groups living in the same society refuse to live together peacefully, and what happens when the majority refuses to share power and grant civil rights to the minority…… The fact that they have been fighting each other for seven years with scarcely a light at the end of the tunnel of violence, should warn us that we, too, could go that way if we allow hate and fear to rule our lives…

“Individuals with equal rights in society” sounded the same on both sides of the pond, “But we have greater advantages,” said the editorial. The ‘Irish problem’ is 800 years old, far older than this country. Northern Ireland’s Catholics have a historical claim to be part of another country to the south, whereas blacks here could in reality only lay claim to unification within a land of their dreams…….

“In this Bicentennial year we have looked back to our roots to remind us who we are and where we came from. It has been a good object lesson. Northern Ireland is also a good object lesson, and it’s live and it’s happening now.”

The series was offered for general U.S. newspaper use by United Feature Syndicate for the week of Jan 30, 1977, but I have no idea how many papers picked it up. Nice plug for it, though: “The conflict is described by the people themselves and is interpreted by a journalist whose background and insight make this an unusually penetrating series.”

Give that man a pay raise!

Back in Cleveland I saw that colleague Sue Kincaid reported on a parent-teacher association survey that Cleveland parents were overwhelmingly opposed to busing, but that the survey was flawed because ‘many non-white schools could not afford to make copies of the survey form for each member.’

In late November Judge Battisti deferred an NAACP request for a citizen advisory panel, worried that it might create a ‘circus atmosphere’ and detract from the main purpose of getting the state and Cleveland school boards to come up with a workable desegregation plan. The School Board came up with its own 46-member citizens advisory panel, but as I wrote on Dec 8 it was ‘like a whale stranded on a beach… and beginning to realize it is almost impotent in offering anything meaningful toward the creation of a school desegregation plan.’ Especially with a Jan 17 deadline.

In December Battisti named a local law professor, Edward A Mearns Jr. to be his Master for creating the plan, and then gave me another front page splash by saying that it had to be city-wide, involve all grades in all schools – and to start no later than next September.

Good luck to that, then.

“Murky days ahead for school desegregation,” said the Press’ lead editorial the next day. Too much ambiguity in his new guidelines. I could only agree with the editor that “In the past year the question of the racial composition of the Cleveland schools has taken many twists and turns. What this week’s events tell us is that the end of the tunnel is not yet in sight and some unexpected turns may yet lie ahead.”

As for me and the missus we have our own new distractions: Our new house, new puppy, and new set of Langlauf cross-country skis. It’s snowing heavily outside, the Chagrin Valley golf courses are open to skiers.

“Blue klister wax?” I ask friend Bob, “or green?” He looks at the weather forecast. “Green, I think.”

“I’ll take blue as well,” I reply, knowing he usually gets it wrong.