7 Highest Expressions of Calligraphy: Tang Dynasty and the Eight Techniques Of 永

Part I. Culture

By all accounts, the Tang Dynasty (唐朝/táng cháo) (618-907) is considered China’s Golden Age, a period of wise governance, prosperity, long-lasting pace and active commerce and trade. The art forms of poetry, painting and calligraphy were fully developed and revered by a host of well-accomplished poets, artists, and calligraphers.

1 Tang Poetry 唐诗/唐詩

During the Tang, Chinese literature, especially poetry, reached its zenith. 李白/lĭ bó (or, lĭ bái), Li Bo or Li Bai, a poet of immortality, attained the title of 诗仙/詩僊/shī xiān (Poetic Genius). Passion, imagination and elegance of expression mark his works – some exceeding 900 verses in total. Even now his poem 静夜思/靜夜思/jìng yè sī, Thoughts on the Silent Night, remains popular.

Likewise, 杜甫/dù fŭ, Du Fu, known as 诗圣/詩聖/shī shèng (Saint of Poem), is another immortal. He wrote at least 1,500 poems. His works are strict in verse, remarkable for their range of mood and content, including his expressions of political and social issues. His 登高/dēng gāo (Climbing Up) attained unmatched perfection.

王维/王維/wáng wéi, Wang Wei, the poet of landscape, wrote hundreds of poems, all elegant and exquisite. Wang Wei was a master of 绝句/絶句/jué jù (a poem of four lines, each containing five or seven characters, with a strict tonal pattern and rhythm). Many of his quatrains depict quiet scenes of water and mist, with few other details or human presence. 相思/xiāng sī (Missing) is one of his most famous poems.

2 Classical Chinese Painting 国画/國畵

Classical Chinese painting, 国画/國畵/guó huà, literally “native painting,” as opposed to Western styles of art, is done with a brush and black ink and/or colored pigments typically on rice paper or silk. The finished work can be mounted on scrolls. The two main techniques are 工笔/工筆/gōng bĭ (meticulous) and 水墨/shuĭ mò (water and ink). 水墨 painting is also called 写意/冩意/xiĕ yì or “freehand style” and known as 文人画/文人畵/wén rén huà (literati painting). Landscape painting, 山水画/山水畵/shān shuĭ huà, was regarded as the highest form of Chinese painting.

国画/國畵 is often seen with calligraphy directly on the picture. Typically, once an artist finished a painting, he would inscribe his name followed by representative seal(s) (印/yìn). Other details could include a date, details about the person for whom the picture was painted, the occasion captured by the painting, even the style of the painting. It was also not unusual for an artist to write a poem or prose that touched on topics from literature and painting to metaphysics and philosophy. What’s so significant is that these inscriptions often provide great insight into a painter’s personality, philosophy and style.

3 Calligraphy

During the Tang and even Sui (隋/suí) (581-619) Dynasties, calligraphy was widely practiced and studied.

3.1 Theories on Calligraphy

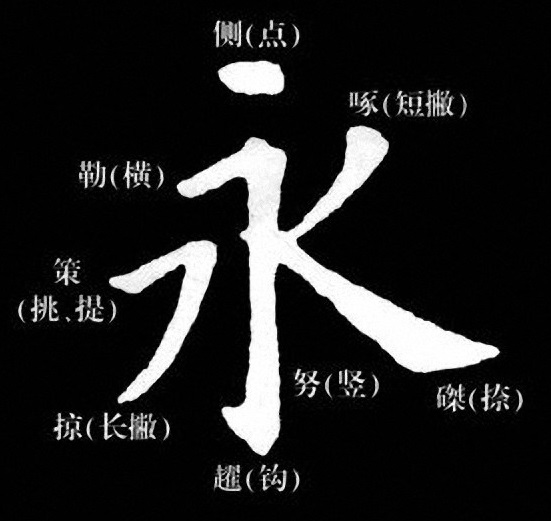

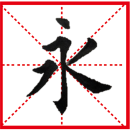

- 永字八法/yǒng zì bā fă: The Eight Stoking Methods in 永 (yǒng) Writing. – 侧/側(点/點), 勒(横/橫), 努(直), 趯(钩/鈎), 策(提), 掠(长撇/長撇), 啄(短撇), and 磔(捺) (dot, horizontal, vertical, rise, long left-falling, short left-falling, and right-falling strokes).

- 锥画沙/錐畵沙/zhuī huà shā: it’s a technique of writing developed by 孙过庭/孫過庭/sūn guò tíng, a master calligrapher, on the basis of earlier practices. It reflects right-stroke writing – to write as drawing on sand with an awl as well as to emphasize 中锋用笔/中鋒用筆/zhōng fēng yòng bĭ, or center-tip writing. This became the standard for centuries.

- 书谱/書譜/shū pŭ, is one of the first documents to systematically record and analyze Chinese calligraphy. Written by 孙过庭/孫過庭 in cursive style, it is often used as an indispensable writing guide.

3.2 Calligraphers and Scripts

Devotion to calligraphy was so all-encompassing during this period that practitioners focused on every major script, leading to the full development of regular and cursive styles.

3.2.1 Regular Style 楷书/楷書

The three sub-styles of regular script were well established at this time. They are 欧体/歐體, 颜体/顔體, and 柳体/柳體. Since then, most calligraphy students start learning 楷书/楷書/kăi shū, regular style, by choosing one of them.

Ouyang Xun (欧阳询/歐陽詢/ōu yáng xún) (557-641 AD), creator of 欧体/歐體/ōu tĭ, ou style, is often considered the dynasty’s supreme 楷书/楷書 calligrapher. Characters have a certain rigidity and strength in style that is also marked by solemnity and grace. His most famous work is the Stelae in the 九成宫/jiŭ chéng gōng, Jiuchenggong Palace.

Yan Zhenqing (颜真卿/顏真卿/yán zhēn qīng) (709-785 AD), is considered one of the most innovative and influential of all Chinese calligraphers largely because he abandoned popular styles of that time and created his own, 颜体/顔體/yán tĭ, yan style. The style has a grandeur and loftiness combined with bold strokes and characters.

Liu Gongquan (柳公权/柳公權/liŭ gōng quán) (778-865 AD), combined the styles of 欧体/歐體 and 颜体/顔體 to create 柳体/柳體/liŭ tĭ, liu style. Notable for its clarity, it gained widespread acclaim especially among high-ranking officials. Liu’s characterization of brushwork – “an upright heart makes for an upright brush” (心正则笔正/心正則筆正/xīn zhèng zé bĭ zhèng) – has become a classic description of how calligraphy reflects an artist’s unique personality.

There were also many other well-established calligraphers during Tang. They include 虞世南/yú shì nán, 褚遂良/chŭ suí liáng, and 唐太宗/táng tài zōng (Emperor Tang Tai Zong).

3.2.2 Cursive Script 草书/草書 and Distinguished Calligraphers

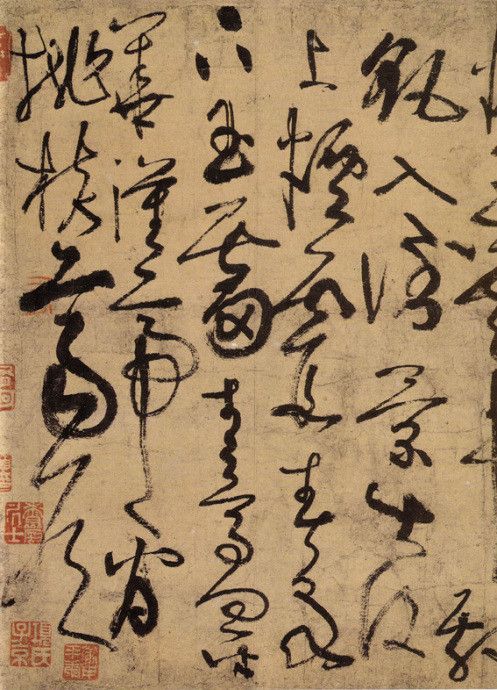

As the originator of wild cursive style (狂草) and a nonconformist in spirit, 张旭/張旭/zhāng xù (approx. 675-750) acted altogether against convention, earning the name “Crazy Zhang.” He was fond of drinking, and while intoxicated, he was inspired and would proceed to create his wonderful cursive calligraphy in front of visiting dignitaries. Figure 2 is one part from his 古诗四帖/古詩四帖/gŭ shī sì tiè (Calligraphy Pieces of Four Classical Poems).

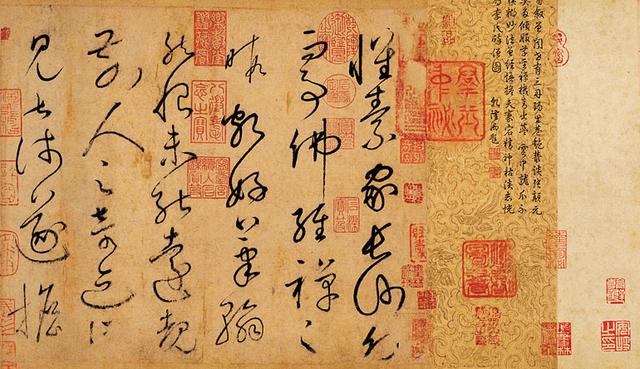

怀素/懷素/huái sù (725-785 AD) is also famous for cursive style. His calligraphy resembled snakes and dragons reeling in storms, lighting, and thunder. In Huai Su’s 自叙帖/zì xù tiè (Autobiography in Cursive Style) (Figure 3), the artist used a fine brush to write larger characters. The strokes are rounded and dashing, almost as if they were steel wires curled and bent. The tip of the brush is exposed where it is lifted from the paper, leaving a distinctive hook – hence the description “silver hooks and steel strokes.” A continuous cursive force permeates the entire piece. The brush skirts up, down, left, and right as it speeds across the paper.

Part II. Calligraphy Writing

1 Strokes

These three strokes consist of one or more turnings. Instructors will show how to change the writing directions (i.e., to make the turning) by adjusting the brushes. One key principle that needs to be kept in mind is to write with the center tip no matter which direction the writing is in.

|

|

|

|

2 Character Writing

2.1 Characters

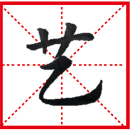

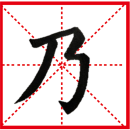

永/yǒng/forever; 艺/yì/art, skill; 乃/năi/to be

2.2 Sample Calligraphy Characters

|

|

|

2.3 Writing by following rules

- Prepare tools and materials.

- Start to write under instruction.

- Be aware of rules for proper posture and of stroke order.

3 Homework

3.1 Characters for practice:

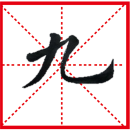

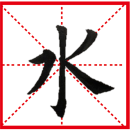

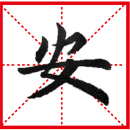

九/jiŭ/nine; 水/shuĭ/water; 安/ān/piece, safe

|

|

|

3.2 Search online to find more information about 永字八法 and see how much the technique sets can help with your calligraphy writing.

Part III Additional Resources

- Three Perfections: https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/three-perfections-poetry-calligraphy-and-painting-in-chinese-art/

- Chinese Calligraphy Main Style & Learn from Rubbings: http://www.skyren-art.com/en/dingshimei/english-articles/127-learn-from-rubbings.html