8 The Song Dynasty: Its Distinctive “Skinny, Golden” Style of Calligraphy

Part I. Culture

1 Two Sub-Dynasties

The Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD), lasting more than 300 years, was divided into two distinct periods: Northern Song 北宋/bĕi sòng and Southern Song 南宋/. During the Northern (960–1127), the dynasty controlled most of what is now Eastern China. The Southern (1127–1279 AD) refers to the period after the Song lost control of its northern half due to its defeat by the Jin (金/jīn, a country to the north of China). As a result, the Song court retreated south of the Yangtze River.

2 Social Development

Generally speaking, the Song is among the greatest in China’s history. Social development flourished. So did technology, science, philosophy, mathematics, and engineering. Inventions included woodblock printing and movable-type printing, leading to the spread of literature and, thereafter, printed forms of information.

3 Song Poetry

Song poetry, called Ci (词/詞/cí), evolved from Tang poetry. Certain fixed-rhythm forms (originally tunes of songs) characterize its poetry. Each poem has a title that specifies a particular fixed pattern of tone, rhythm, number of syllables (or characters) per line and the number of lines. Surprisingly it has little or nothing to do with a poem’s content. Prominent Song poets include Su Shi (苏轼/蘇軾/sū shì), Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修/歐陽脩/ōu yáng xiū), Lu You (陆游/lù yóu), Yang Wanli (杨万里/楊萬里/yáng wàn lĭ), and Li Qingzhao (李清照/lĭ qīng zhào).

4 Calligraphy

Four master calligraphers were revered during this time. They are 苏轼/蘇軾, 黄庭坚/黃庭堅/huáng tíng jiān, 米芾/mĭ fú, and 蔡襄/cài xiāng.

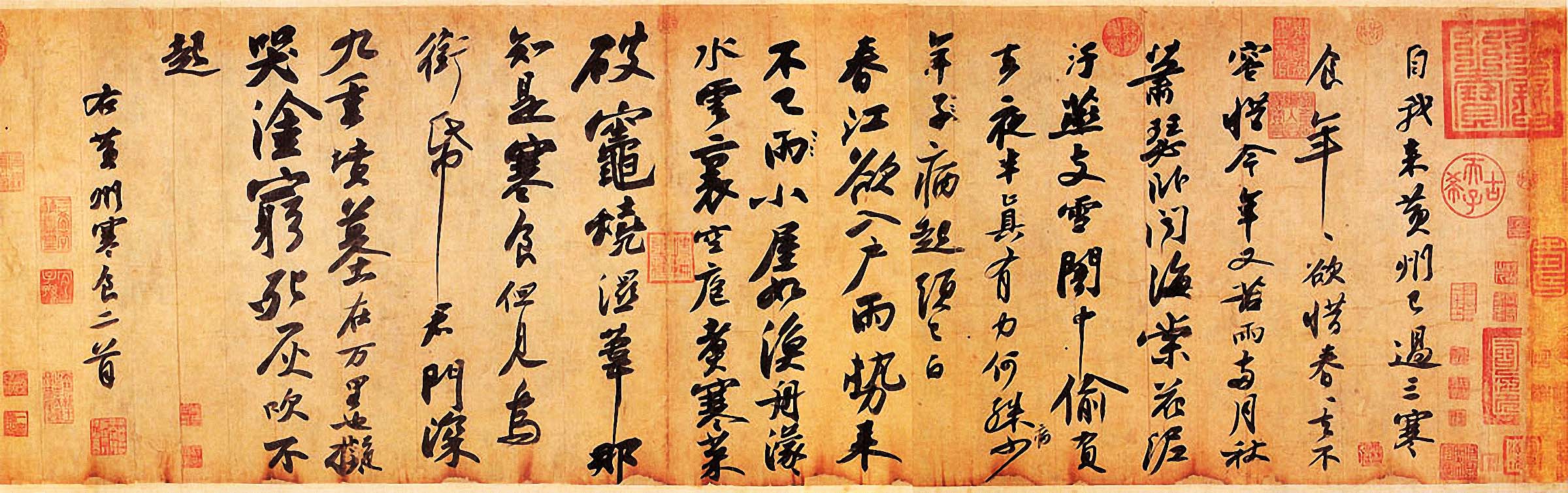

Su Shi (苏轼/蘇軾, 1037-1101), also known as Su Dongpo (苏东坡/蘇東坡), was a well-known writer, painter and calligrapher. He combined the technique of painting with that of calligraphy, emphasizing freehand brushwork that could express his own impression or mood. His thinking was that, like a person, the essentials of good calligraphy should include the soul, flesh, bone, blood, and vital energy. A beginner should first learn to write in regular script, he claimed, so as to gain solid mastery of other styles of calligraphy. This view has been widely acknowledged even today. Representative Su’s works include 寒食帖 (Inscription of Hanshi) (Figure 1), 赤壁赋/赤壁賦/chì bì fù (Red Cliff Rhapsody), etc.

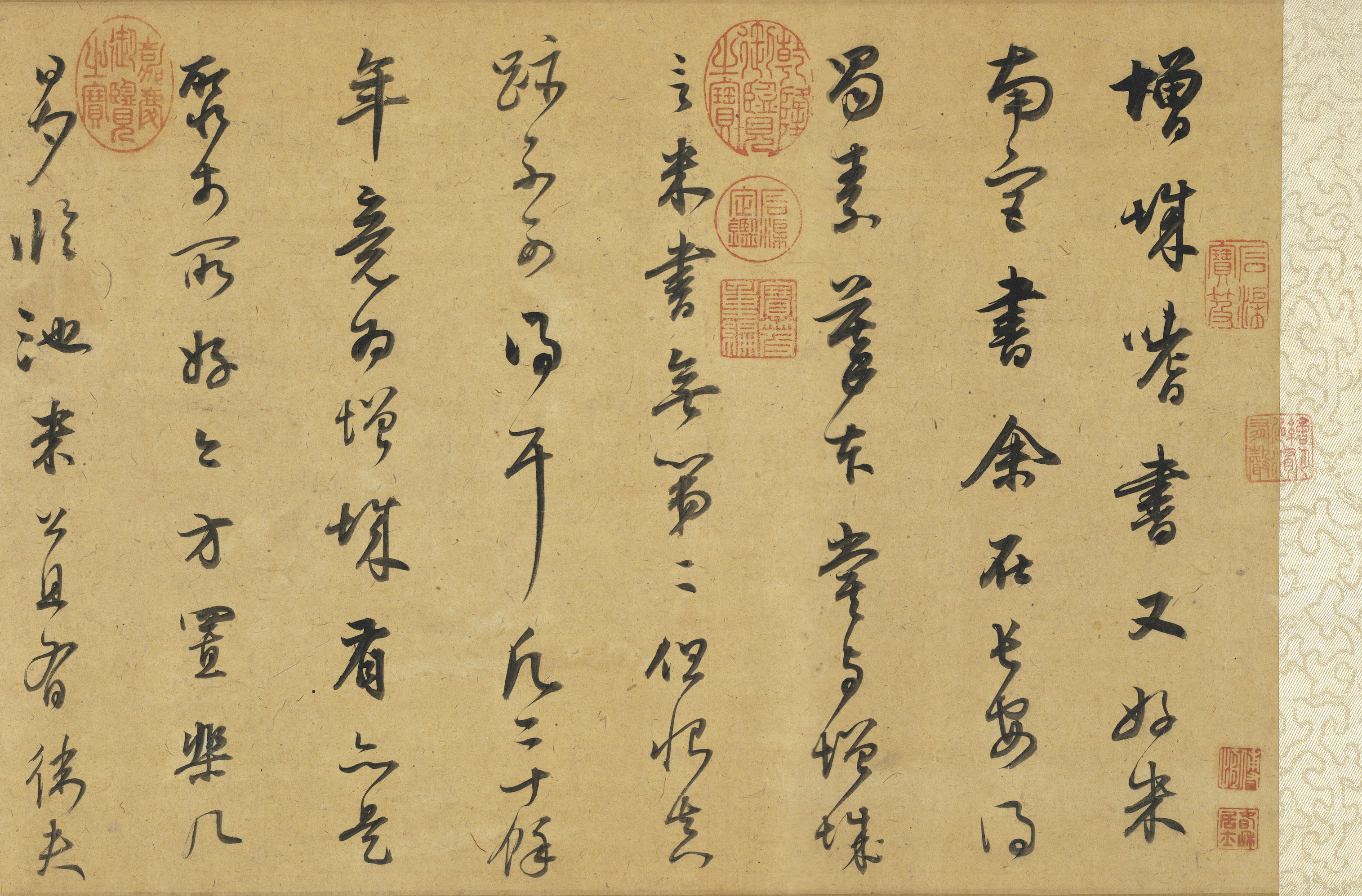

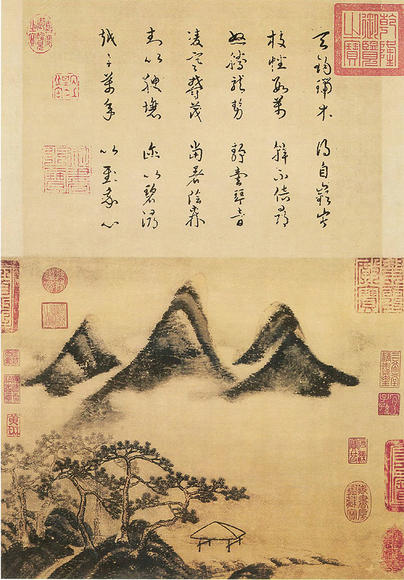

Mi Fu (米芾/mĭ fú) (1051-1107) was a great calligrapher, calligraphy critic, and a painter known for landscape drawings and character sketches. As a calligrapher, he held a mastery of all writing styles. His representative works include the 蜀素帖/shŭ sù tiè (Poem of Shu Su) (Figure 2), 瑞松图/瑞松圖/ruì and sōng tú (Poem of Picturesque Pavilion) (Figure 3), etc. As a calligraphy critic, his works such as the 书史/書史/shū shĭ (History of Calligraphy) show deep insight into the essence of calligraphy. For example, Mi Fu suggested that one should always study authentic ancient calligraphy rather than copying rubbings from stone inscriptions.

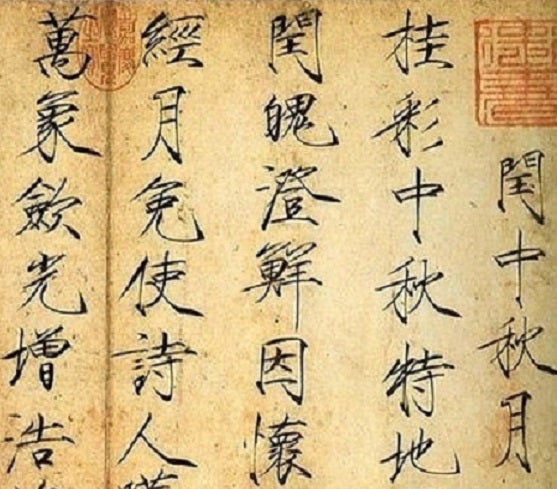

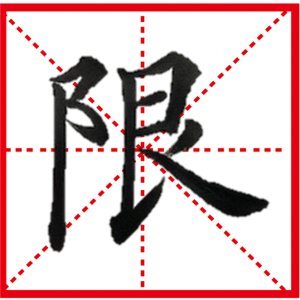

In addition, Emperor Huizong (宋徽宗/sòng huī zōng, 1082-1135) of the Northern Song, although politically fatuous and incompetent, was also a calligrapher and painter of great reputation. He originated the 瘦金体/瘦金體/shòu jīn tĭ (Skinny Golden Style) featuring thin, sturdy strokes in contrast to conventional norms (Figure 4).

Part II. Calligraphy Writing

1 Calligraphy Techniques

圆笔/圓筆/yuán bĭ and 方笔/方筆/fāng bĭ are a pair of related techniques that reflect Yin and Yang in order. When should 圆笔/圓筆 or 方笔/方筆 be used in a character or piece of calligraphy? A general principal is to maintain a good balance between Yin and Yang.

1.1 Round-shaped Strokes 圆笔/圓筆

圆笔/圓筆 refers to a stroke part that is to be written in a round shape. These parts can form the beginning, ending, or a particular turning. The 圆笔/圓筆 can be made in two ways. The beginning or ending of a stroke can be done with concealed tips (藏锋/藏鋒/cáng fēng), the turn by writing a smooth curve. See the circled stroke parts in figure 5.

1.2 Square-shaped Strokes 方笔/方筆

方笔/方筆 is a stroke shape that takes in a square-like form. Being angular or sharper, 方笔/方筆 happens also at the beginning, turning, and ending parts of a stroke. To produce a 方笔/方筆 beginning or ending, the brush doesn’t need a backward stroke. See the squared stroke parts in Figure 5.

![]()

![]()

Figure 5: 圆笔/圓筆 and 方笔/方筆

2 Stroke Writing

These two strokes are each part of a radical. To write both strokes well, a calligrapher should start with a short 方笔/方筆 horizontal, then make a 方笔/方筆 turn, and complete the rest.

3 Characters

3.1 Stroke Order

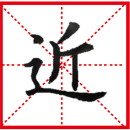

Arch Chinese lists 12 rules of Chinese character writing order. Below is Rule 12:

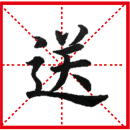

- Rule 12: Inside before bottom enclosing (e.g., 近, 送, and 巡)

For details, visit the Arch Chinese website. Yellowbridge Online Dictionary can also provide additional information.

3.2 Characters

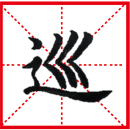

限/xiàn/limit; 近/jìn/near; 邪/xié/evil

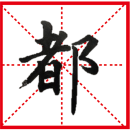

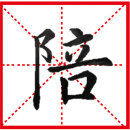

3.3 Sample Calligraphy Characters

3.4 Writing by following rules

- Prepare tools and materials.

- Start to write under instruction.

- Be aware of rules for proper posture and stroke order.

4 Homework

4.1 Write the following characters:

巡/xún/patrol; 送/sòng/to send; 都dōu/all, both; dū/capital; 陪/péi/to accompany

4.2 Search on line to find out how to apply an Yin-Yang balance to Chinese calligraphy writing.

Part III. Additional Resources

- Northern Song Dynasty: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nsong/hd_nsong.htm

- Mi Fu: http://www.chinaonlinemuseum.com/calligraphy-mi-fu.php

- Song Dynasty Art, Painting and Calligraphy: http://factsanddetails.com/china/cat2/4sub9/entry-5478.html

- Calligraphy in Five Dynasties, Northern and Southern Song Dynasties: http://treasure.chinesecio.com/en/article/2009-08/25/content_12809.htm