Part III: The Italian Community of Cleveland

Chapter 10: Italian Ethnicity in Cleveland: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow

From Traditional Neighborhoods to the Suburbs

In recent years there have been written several accounts relating to the decline of ethnicity in Cleveland. We have been reminded of the deterioration of the traditional nationality neighborhoods, of the rapidly decreasing population of these areas, and the general lack of interest in their rejuvenation.[1] It has become axiomatic that the reduction of a particular nationality population within the city is to be equated with the general demise of ethnicity. By using this criterion we should assume that ethnicity is a dying phenomenon, retreating before the forces of assimilation, depopulation and apathy.

And, in fact Cleveland’s ethnic communities are slowly losing their population. In particular the Italian element in the city has undergone a reduction in the decade since the 1960 census. In that year there were nearly 20,000 first-and second-generation Italians living in the city. This figure was reduced to 17,693 in the 1970 census. A conservative projection would be that by the 1980 census less than 14,000 Italian-born Clevelanders will remain within the city’s boundaries.

What is more noticeable is the shift in the Italian population away from the traditional neighborhoods and into the suburban communities. Indeed, each of the five major Italian settlements in Cleveland proper has suffered significant losses in population in the last two census reports. Table G in the Appendix indicates this comparative loss which may be summarized here:

| Little Italy | Collinwood | Mt. Carmel (East) | St. Rocco’s | |

| 1960 | 1965 | 2371 | 2164 | 804 |

| 1970 | 975 | 1271 | 247 | 597 |

Although these figures indicate a substantial population reduction in the Italian-born population they do not totally reveal the situation. A more recent indicator of population, the 1976 election returns by ward, illustrate even further reductions in Italian population within the city. For example, Ward 19, Little Italy, had less than 500 Italian-surnamed individuals registered to vote.[2] In the Collinwood area less than 1200 were listed while in St. Rocco’s area some 450 Italian-surnamed voters were registered. Since the voting age has been reduced to 18 it would be expected that a much larger figure would be found. But that was not the case. Another indicator of the decreasing population among the young in Murray Hill was that one of the proposals of the Cleveland Public Schools Desegregation Plan was to close Murray Hill School because of the decline of enrollment in that traditionally Italian school.

Italians are no longer immigrating to Cleveland to the same extent which they have done in the past. Although the number of Italian immigrants to the United States has averaged about 20,000 per year since 1970, they have not migrated to Cleveland in proportion to their immigration. One statistic which illustrates this point is the numbers of Italians naturalized in Cleveland since 1970. These figures are presented below:[3]

| 1970: 49 | 1973: 152 |

| 1971: 59 | 1974: 129 |

| 1972: 176 | 1975: 70 |

The declining trend will continue not necessarily because of apathy but because fewer Italians are entering the city. The once strongly attracting effect of a growing Italian-American community in Cleveland is no longer present. Recent Italian immigrants are remaining along the northeastern coastal cities while east Europeans, especially Yugoslavians, have increasingly found Cleveland a hospitable community and thus have increased their migration to the city.

The Italian population of the city is undisputably declining but this does not necessarily indicate a weakening of Italian ethnicity. Using the concept of “ethnic corridors” we can explain that the Italian population of Cleveland is being dispersed into the suburban areas even to the extent of once again creating Italian spheres of influence. According to the 1972 Levy Report, Italians in the community of Seven Hills represented one of the three major ethnic groups in that city.[4] In Lyndhurst 27% of the foreign-born population are of Italian extraction, while Italians make up over 10% of the foreign born in the city of Euclid.

These ethnic corridors for the Italian community may be said to include various avenues of inter-city migration. In the eastern suburbs they would include Euclid, Lyndhurst, South Euclid, Cleveland Heights, Garfield Heights and Mayfield Heights. On the west side Parma has perhaps the largest Italian concentration with over 2200 Italians. Seven Hills also includes nearly one thousand Italians within its boundaries. According to the 1970 census these growing Cleveland suburbs had the following Italian population:[5]

| Total Population | Italian Population | |

| Euclid | 71,552 | 2503 |

| Parma | 100,211 | 2380 |

| Cleveland Heights | 60,756 | 1757 |

| Garfield Heights | 43,800 | 2060 |

| South Euclid | 29,611 | 2871 |

| Lyndhurst | 19,749 | 1856 |

Within the city of Cleveland those Italians who have remained have reformed some communities but without the full complement of ethnic flavor normally associated with such a neighborhood. This regrouping has been primarily occurring on the south and west sides where the population has increased. For example, along Puritas and Bellaire Avenues contained in Census Tracts 1242, 1245 and 1246, nearly 800 Italians were listed during the last census. They live in an area which also includes Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians and Germans. On the near west side along Detroit Avenue from West 45th to West Boulevard about 700 Italians have formed a colony. Yet these are only pockets of Italian-American settlers and do not necessarily reveal an ethnic community. In the last analysis then, ethnicity does not mean merely population but also must include a sense of association, a feeling of Italianità.

The question which legitimately can be raised is, has the declining ethnic population in the traditionally Italian neighborhoods minimized the influence or involvement of Italian-Americans in those neighborhoods? Also, does this decline in numbers also diminish the impact of the Italians upon the city itself? To a degree there must be some correlation between influence, involvement, and population, but not necessarily to the extent one would expect.

With regard to the old neighborhoods they still act as a magnet to draw their suburban children back to their streets and shops every weekend. As one former resident put it, “People who live on the ‘Hill’ love it, but you don’t have to live here to know that feeling.” It seems that actual habitation in an area is not necessary to experience a sense of cultural identity.

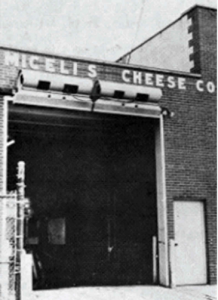

The attractions of Italianità are as varied as the individual Italo-Americans who return to the neighborhoods, each seeking his or her own level of identification and participation. In Murray Hill the Mayfield Importing Company is as crowded as any specialty shop on any given Saturday. For those who can more easily identify their “Italianness” with food their search ends among the savory prosciutto and mortadellas of Mayfield Importing and with the crusty breads of Presti’s or Corbo’s bakeries. In the evening the major Italian restaurants on the Hill, such as the Roman Gardens, Mamma Santa’s, the Golden Bowl, Guairino’s and Theresa’s, cater to Italian and non-Italian diners.

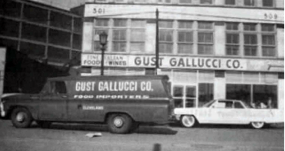

In downtown Cleveland Gallucci’s and Bonafini Imports still attract hundreds of shoppers daily while Zannoni’s on West 35th and Clark Avenue fulfill the needs of the west-side Italians. Orlando Baking Company supplies hundreds of Cleveland businesses daily with its many varieties of baked goods. Still located along Woodland Avenue near East Boulevard, it has been a Cleveland enterprise since the turn of the century.

But ethnicity isn’t only based on food or on mere numbers of people. It is a commitment coupled with an intangible feeling of identity. It is the extended sense of attachment to a special group with whom you can identify and are accepted. It is, in essence, an extension of one’s being beyond being an American to another dimension of existence.

This “extension of the self” can be seen in the numerous ethnic societies within the Italian community. Italians have always evidenced a decentralized organizational format, and for this reason appear to be fragmented and disunified. There are only a few national Italian organizations in the city, specifically the Sons of Italy and the Italian Sons and Daughters of America. Instead one can still find an assortment of local hometown societies, ward clubs and cultural organizations within the city. A sample listing of those presently in existence illustrates their regional diversity:

Noicattarese Club

Italian Cultural Gardens Association

North Italian Club

Baranello Woman’s Auxiliary

Calabrese Club

Imerese Lodge

Ripalimosani Men’s Union

Italian Workers Society

The Trentina Club

St. Anthony’s Club

A complete listing can be found in the 1974 Nationalities Directory. Like the family these organizations were founded and continue to function for the benefit of their local membership. Decentralization has proven to be a strength for these organizations rather than a weakness, for they have brought together people from the same region and town, people who have many common experiences to share.

An estimate of the functioning Italian clubs and lodges in the city is about 50.[6] They include cultural, professional, service, social and fraternal groups. With the Slovaks, Poles, Slovenians and Czechs, the Italians have the largest number of organizations within the city of Cleveland. This kind of activity illustrates a more positive aspect of ethnic awareness, beyond mere association to active participation.

Italians in Cleveland Politics

Besides Italian-oriented societies and activities, in what other areas is there evidence that Italians are an influential group in the city? Politics have usually been the stepping stone for ethnic groups to move up the social and economic ladder, and Italo-Americans are no exception. In Cleveland only a handful of Italians, however, have ever been elected to an office, while many have received appointed positions.

Beginning with the election of Alexander De Maioribus to City Council in 1928 from the predominantly Italian 19th Ward, Murray Hill has always returned an Italian councilman. In 1947 George Costello took over the seat held by De Maioribus and was followed by Paul J. De Grandis, Jr. in 1957. Michael Fatica succeeded De Grandis in 1961 and was later replaced by Anthony Garofoli. Currently Basil Russo represents the voters of the 19th Ward.[7]

Other Italian councilmen elected in Cleveland over the years include Alfred Grisanti from Ward 31 in 1943 and Ernest C.T. Santora from Ward 21 in 1957. In 1972 with the election of Mayor Perk, four Italian Americans were listed in the City Council: Joseph A. Lombardo from Ward 2, Michael Climaco from Ward 5, Basil Russo, Ward 19 and Ben Zaccaro, Ward 26. Currently three Italian Americans serve on the council.[8]

The most successful Italian-American politician in Cleveland was Anthony J. Celebrezze. Born in Anzi, Italy, on September 4, 1910, he was brought to this country at the age of two. Educated in the Cleveland Public Schools and at John Carroll University, he received his law degree in 1936. His political career began in 1950 when he won election to the Ohio Senate. As a member of several important committees he was twice voted as one of the state’s top senators.

His work in the Senate attracted the attention of Cleveland’s voters. In 1953 Celebrezze ran for mayor of the City of Cleveland and was elected. He brought into his administration eleven Italian-Americans to serve in various administrative capacities. Joseph Ventura was appointed as secretary to the Mayor. Louis Corsi and Salvatore A. Precario were appointed as assistant directors in the Civil Branch, while Charles W. Lazzaro headed the Criminal Branch. The Director of Public Properties was John J. Lucuocco.

Mayor Celebrezze served four terms as mayor and during the fifth elected term was appointed by President Kennedy to be Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare in July of 1962. He served in that capacity until 1965 when he was appointed Judge of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals. On July 20, 1973, by an act of the United States Congress, the new federal building in Cleveland was named the Anthony J. Celebrezze Federal Building in honor of the former mayor of Cleveland and prominent Italian-American.

The name Celebrezze was not new to Cleveland politics. In 1937 Governor Martin L. Davey appointed Frank D. Celebrezze, brother of Anthony Celebrezze, to the municipal bench in Cleveland. He was the first Italian-American judge so appointed and, as it turns out, not without the assistance of Alexander de Maioribus. According to one source de Maioribus, a Republican, spoke with the Governor on Celebrezze’s behalf, showing the need for an Italian judge in Cleveland. The influence was there and the Republican councilman succeeded in getting a Democrat appointed.

Other Italians have been appointed to administrative positions by various mayors. During the terms of Mayor Locher (1962-1968) one Italian-American, Vincent De Melto, was appointed Director of Public Utilities. Under Mayor Stokes, S.R. Calandra and J.P. Mancino were assistant directors of the Civil Branch of the city, while B.J. Zaccaro and T.J. Italiano were directors in the Criminal Branch.

It is interesting to note that during the first year in office Mayor Stokes had drawn up a xerox listing of appointees entitled Personnel of Ethnic Backgrounds in Responsible Positions in the Administration of Mayor Carl B. Stokes. Eighteen ethnic groups were listed as having members in the Stokes’ administration. Twelve Italian-Americans were listed as being top administrators. In fairness it should be stated that most of these men were under civil service appointment and held their positions by the grace of law rather than by political patronage.

Two notable Italian-Americans in the administration of Mayor Perk are Law Director Vincent Campanella and J.A. Zingale as Acting Director of the Department of Public Properties. Several commissioners include S.T. Sturniolo in Architecture, Acting Commissioner of Streets J. La Riccia, and L. Civittolo in the Department of Finance. Additional Italians are included on the Community Relations Board, the Board of Zoning Appeals and the Board of Building Standards.

Italianità in Cleveland’s Colleges, Universities and Schools

In the field of education Italian-Americans are found on the faculties of every local public and private university and college as well as in the public school system. Traditionally Italians did not place a great deal of emphasis on formal education. To earn a living as soon as possible was the major concern of most Italian-American families and educational priorities were placed accordingly. Even as late as the 1970 census only 7% of Italian-Americans over 25 years of age were college graduates, a figure well below other ethnic groups. But since the post-war period some inroads have been made in the emphasis placed upon formal education and this is reflected by the numbers of Italo-Americans currently holding faculty status in the various educational sectors.

At Cleveland State University about 15 faculty members are of Italian descent dispersed throughout the sciences and humanities. Case Western Reserve University, with a much larger faculty, has less than 20 Italians, while John Carroll University lists about 13 as being full-time members of the teaching staff.

The Cleveland Public Schools have some Italian-Americans who serve as supervisors in the various disciplines. In 1976 eight individuals were listed as holding either supervisory or assistant supervisory positions.[9] Within the schools themselves about 15 individuals of Italian descent are principals or assistant principals in the system of some 180 schools. Italian-American teachers are to be found in the schools, some of whom head large departments. The names Iammarino, Caliguire, Mileti, Conti, DiScipio, Contini, Russo, Rosi and DeMarco identify just a few of the many educators within the public schools who have provided Cleveland students with models of achievement.

What is currently offered in the way of Italian-oriented curriculum in Cleveland’s institutions of higher education? At most colleges introductory and intermediate Italian language classes are presently offered. Italian literature is not offered at any institution in Cleveland although theoretically Italian writers are included in survey courses in Comparative Literature. Interestingly enough, Kent State University lists 14 courses in Latin Literature, three in related Greek courses and nothing in Italian literature. John Carroll offers almost 25 courses in the Classics but only four courses in modern Italian. It should be mentioned that one of the proposals made by the Cleveland Public Schools desegregation plan was to fund a Foreign Language and Cultural Center at Cleveland State University. Russian, Chinese, Czech, Hebrew, Latin and Italian were among those tentative courses which would be available but only the Russian and Chinese programs were given first priority.

At the college level there are several institutions which have offered general courses in ethnic studies. At least one university, John Carroll, presented a course specifically in Italian-American history. At the high school level, especially in the parochial schools, separate courses in ethnicity have been developed and are presently being taught. In the public schools at least two schools offer ethnic studies, while units on immigration and general ethnicity have been incorporated into the traditional American Studies curriculum.

During the 1974-75 school year the Cleveland Public Schools, in cooperation with Cleveland State University, did sponsor the Ethnic Heritage Studies Program which developed and implemented multi-ethnic curriculum materials. Although not designed to concentrate on any single group but rather to incorporate many of the sixty ethnic peoples within its curriculum, some materials specifically focused on the Italian American experience in Cleveland. One filmstrip, “Ethnic Neighborhoods in Transition,” traces the origins, growth and development of the Italian, Jewish, Black, Ukrainian and Hungarian communities in the city. Another media presentation, “What is an Ethnic Group?” uses several Italian area landmarks in the city to describe the meaning of ethnicity.[10]

The Italian-American Media in Cleveland

Unlike several other major groups in Cleveland such as the Polish, Hungarian, Slovenian, Czech, German and Romanian, the Italian community does not have a locally published newspaper. At one time Cleveland had two papers for the Italian communities, La Voce and L’Araldo, and the Italian Pictoral News and The Latin World. La Voce, founded in 1904 by Olindo and Fernando Melaragno, ceased publication in 1944. L’Araldo came into existence in 1938 and, under the leadership of Louis De Paolo, continued until 1959.

The most enduring Italian-American publication in America, Il Progresso Italio-Americano, is published in New York City and is sent to Cleveland daily. Il Progresso along with imported Italian language magazines and newspapers such as Oggi and Milan’s Corriere della Sèra can be purchased at Schroder’s Book Store on Public Square. Two new magazines, The Italian American and Identity, are also sold in local newsstands and bookstores.

At the beginning of 1977 Cleveland had approximately 12 hours of Italian language broadcasting on five different radio stations. The sudden announcement in February of 1977 that station WXEN, the all-nationalities station, was changing its entire format, reduced all ethnic broadcasting substantially and the Italian air time dramatically. For the Italian-American community programming was reduced to only six hours weekly and then usually on “non prime time” during the weekends. Familiar commentators and broadcasters such as Louis De Paolo, Joe Giuliano, Carl Finocchi, Vincent Cardarelli and Emanuel Diligente had brought local and international news in Italian to thousands of avid listeners. Usually recruiting their own advertisers and working on marginal salaries, they provided a sorely needed service to the Cleveland community. Sadly, it seems that these efforts and community-oriented broadcasting are gradually coming to an end.

The person seriously interested in individual study of Italian language and culture will find that Cleveland area libraries offer some outstanding collections of Italica. The Cleveland Public Library has over 9500 volumes in Italian, ranging from the classics to serious historical works and specialized biographical studies. Also of interest are some collections of Italian genealogical materials which could be valuable in the tracing of one’s Italian ancestry. Frieberger Library of Case Western Reserve University also has a number of works in Italian and English on the culture of Italy. Of particular value is the periodical section, which has nearly every major scholarly Italian journal currently available.

John Carroll University has a unique collection of some 2000 literary works in Italian, concentrated primarily on the literature of the country. They are part of the bequest of Il Cenacolo Italiano, the Italian cultural society in Cleveland. Each year monies are made available by the Society to the Grasselli Library at John Carroll to purchase additional works. It is a praiseworthy effort which has significantly contributed to the promotion of Italian culture in Cleveland.

Il Cenacolo

Il Cenacolo dates to the late 1920’s when the idea of an Italian Cultural Club in Cleveland was conceived. Originally known as “Il Circolo” (The Circle) it was founded in 1928 by the Italian Consul Antonio Logolusi, Professor Joseph L. Bogerhoff, Dr. Nicola Cerri, Judge B.D. Nicola and others of Italian and non-Italian extraction. Inspired by and patterned after La Maison Francaise, the organization aimed at keeping alive the Italian language and culture in this city. Its first president and perhaps most influential single force was Professor Borgerhoff.

In 1932, at the suggestion of Count Buzzi Gradenigo, “Il Circolo” was rebaptized with the present name of Il Cenacolo Italiano and began to attract new members such as Dr. William M. Milliken, former president of the Cleveland Museum of Art and Dr. Orfea Barricelli of Western Reserve University. Il Cenacolo is another name for Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, but in this case simply means an intimate group of friends who are interested in the arts in general and in Italian culture in particular. It is a spiritual link between Italy and the United States.

In addition to the collection of books at the Grasselli Library and an annual scholarship for the study of Italian, Il Cenacolo offers a number of lectures during the academic year. Usually meetings are held in members’ homes and, except in rare instances, all proceedings and lectures are given in Italian. During the program year of 1976-77, Il Cenacolo numbered about 50 members with honorary memberships received by Mario Anziano, Italian Consul to Cleveland, and Maestro Lorin Maazel, conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra.

The Future of Italian Ethnicity in Cleveland

What is the future of the Italian-American community in Cleveland? Will the traditional neighborhoods remain until the next century or will they succumb to the fate of many of urban America’s communities? Will the various fraternal, social and cultural organizations continue to flourish or will they dwindle in size and disappear? Indeed, will we be able to intelligently speak of an “Italian-American Identity” in the twenty-first century, or any other form of ethnicity for that matter?

An interesting answer to this question was supplied by Glazer and Moynihan in their book Beyond the Melting Pot. Although written in 1963, their analysis of today’s trends in ethnicity may have some bearing on tomorrow’s realities:[11]

Religion and race seem to define the major groups into which American society is evolving. . . as the specifically national aspects of ethnicity decline. . . the next stage of the evolution of the immigrant groups will involve a Catholic group in which the distinctions between Irish, Italian, Polish and German Catholics are steadily reduced by intermarriage. . . (Thus) religion and race define the next stage in the evolution of the American peoples.

Will we in Cleveland in fact merge into a consciousness dictated solely by race and religion rather than by national identities?

As long as the search for individual awareness continues, and until we have become so transparent culturally as to accept a composite definition of ourselves, we will have little to fear. However, unless perpetuation of ethnic awareness is sanctioned and legitimized by more than token acknowledgements from local, state and most especially federal agencies, the diversity of our peoples will indeed merge “beyond the melting pot” into an amorphous entity devoid of cultural vitality. Ethnicity will then become only a pursuit for antiquarians and have no adaptibility beyond the confines of the library and the university.

But this does not seem to be the case in Cleveland. We can still enjoy fine Italian cuisine in Murray Hill, attend an all-Italian concert at the Art Museum, listen to an Italian radio program, borrow a book in Italian while still living in Euclid, Parma or Cleveland Heights. The opportunities for those who seek their cultural roots are there if the time is taken to look.

For the Italian-American, with such a rich heritage in this country and in this city, the necessity for re-evaluation of his or her past becomes more than a request. There is the compelling urge for each to contribute his or her individual texture to the pattern of a unique cultural experience to that still unfinished mosaic which is American society. As long as the Italians of Cleveland continue to ask questions and seek answers about their past as well as the promises of the future, both as individuals and as a group, ethnicity will remain a viable force within this community.

Perhaps the Italians in Cleveland are no longer centrally located and perhaps the old neighborhoods are in decline. But the concept of Italianità still exists and will continue to nourish those who but take the time to partake of the bountiful cultural heritage which it offers. Ethnicity has indeed become and will remain a movable feast within the Italian-American communities of greater Cleveland.

- See the Plain Dealer Magazine account for August 1, 1976 on Murray Hill by Joe Crea. A more positive assessment of "the Hill" is offered by Kenneth F. Seminator's "Memoirs of Murray Hill" in the Cleveland Magazine, August, 1976, pp. 48-54. ↵

- Register of Electors, 1976, Cleveland, Ohio. I would like to express my appreciation to Mr. William Kubes, Deputy Director of the Board of Elections, for his assistance in this aspect of my research. ↵

- Annual Report of the Immigration and Naturalization Services, 1970-1975. ↵

- Donald Levy, A Report on the Location of Ethnic Groups in Greater Cleveland (Cleveland: Cleveland State University, Institute of Urban Studies, 1972) p. 23. The 1970 Census reported 964 Italians living in Seven Hills. ↵

- Population According to Census Tracts, Cleveland, 1970. ↵

- Data taken from the Greater Cleveland Nationalities Directory, 1974, pp. 87-92. ↵

- The City Record of the City of Cleveland, 1928-1977. ↵

- Ibid., Wednesday, February 2, 1977. ↵

- Directory, Cleveland City School District, 1975-76. ↵

- The Cleveland Ethnic Heritage Program. Filmstrips and bound materials are available through the Department of Social Studies, Cleveland Public Schools, Room 400, 1380 East Sixth Street, Cleveland, Ohio 44114. ↵

- Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot (Cambridge: M.T.T. Press, 1963) pp. 313-314. ↵