Part II: Italian Immigration and Settlement

Chapter 6: Anti-Italian Sentiment in America

By 1903 there were about 1,200,000 Italians in the United States, 12% of whom lived in the ghettos of the New York City area. In 1903 another 200,000 Italians had arrived, mostly from the Mezzogiorno, and they were followed by another 193,000 the next year. Nearly 286,000 more flocked to Ellis Island and Castle Gardens in 1907, marking a peak in the influx of Italian aliens. By 1921, when the first quota act was passed by Congress, the Italians had surpassed the Irish as the second largest foreign-born group in America after the German Americans.

They poured into the ghettos of New York City, the “Little Italy’s” of Cleveland, New Orleans, Chicago and San Francisco, and found shelter and companionship in the company of their fellow townsmen, campanilismo. But with their growing numbers they generated first an uneasiness, then contempt, finally overt discrimination from Anglo-Americans and other ethnic groups against this new man, the “WOP.” Prior to the twentieth century there were indications that the southern European was indeed part of that “wretched refuse” referred to by Emma Lazarus, whose poem The New Colossus is inscribed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty.

Thomas Bailey Aldrich expressed his “poetic” concern for this infusion of aliens into the bloodstream of civilized America in his poem, The Unguarded Gates (1895):

Wide open and unguarded stand our gates

and through them presses a wild motley throng

Men from the Volga and Tatar Steppes

Featureless figures of the Hoang-Ho

Malayan, Scythian, Celt and Slav

Flying the old world’s poverty and scorn . . .

Although Italians were not specifically singled out they were considered by many Americans as part of the “motley throng” which passed through America’s immigration stalls. John Fiske, traveling in Italy, printed his observations that “The lowest Irish are far above the level of these creatures (Italians)” while the great Emerson rejoiced that the early immigrants brought “the light complexion, the blue eyes of Europe” rather than “the black eyes, the black drop” of southern Europe. Before a congressional committee investigating Chinese Immigration in 1891 a west coast construction boss commented that “You don’t call . . . an Italian a white man . . . an Italian is a Dago.”[1]

What prompted this attitude toward Italians as swarthy, lawless, poverty ridden drones upon the American culture and society? What caused the environment in which a poor immigrant becomes a “dago” or “wop” while a wealthy one is immediately associated with the Mafia, and where the stereotyped organ grinder, anarchist, and mafioso become synonomous with the Italian? The answers have their basis in both the fictionalization of the immigrant and in isolated but nevertheless concrete realities associated with the Italian.

Even a cursory examination of anti-Italian sentiment in America will substantiate the charge that they have been and continue to be subjected to some of the most scurrilous campaigns ever directed against any ethnic group. This chapter in the history of the immigrant should be told, if for no other reason than to make people aware that no ethnic group or racial minority has ever been spared from experiencing the trauma of prejudice and intolerance. Italians were lynched in the South as were blacks, in some cases for permitting blacks equal status with whites in their shops. “No Irish Need Apply” signs had their Italian counterpart in the industrial centers of America. “Teutonic” arrogance against the Jew was also directed against the southern Italians in that pseudo-historical, quasi-sociological “classic,” The Passing of the Great Race by Madison Grant (1916). Prejudice, intolerance, the degradation of others to gratify one’s own sense of superiority, are not confined to one group to the exclusion of all others. Many have felt the impulse to create the fantasy of superiority through the downgrading of others. Individually it is occasionally tolerated as a personality quirk. When it becomes a collective and prolonged effort it can lead to genocide.

To overemphasize and to become obsessed with this particularly unpleasant episode in the history of any ethnic group eventually reaches a point of diminishing returns when the question of harmonious inter-ethnic relations is concerned. In every instance one group will continue to be seen as the oppressor even though the particular events involved may have occurred many years before the present confrontation. To pretend that prejudicial activity never occurred creates a myopic illusion, for one who is totally ignorant in this regard is liable to participate in its repetition against another group. To be aware of all aspects of one’s cultural heritage is essential. But to crouch behind the prejudices of the past as a shield to justify present social, economic or political militancy invites only criticism. Artificial “justifications” relying on historical precedents rarely explain present realities and only confuse the issues. With this thought in mind we turn briefly to examine some of the underlying causes for a feeling of hostility toward Italian Americans which have their roots in late nineteenth century America.

With their numbers increasing yearly in the eastern cities, the presence of Italians took on a sinister form in the 1880’s and 1890’s. Pushed together in the squalor of the urban ghettos such as Mulberry Bend in New York, or the North End in Boston or the West Side near Hull House in Chicago, some manifestations of crime were inevitable in tenement environment. Despite newspaper diatribes against Italians, and most especially against southerners, police reports in Boston and New York City indicate that Italians were no more of a criminal element than any other foreign-born group in the city. In Boston the Italians numbered 7% of the population, yet their arrest rate was 6.1% of the total foreign-born. New York City counted Italians as 11.5% of its population in 1903, yet their arrest rate was about 12% of the foreign total. Indeed, as late as 1963 James W. Vander Zander pointed out that the rate of criminal convictions among Italian immigrants was less than that among American-born whites.[2]

Yet statistics do not dispel fears created by personal experience. There is no doubt some truth in the argument then stated that some Italian criminals were deportees from Italy to this country. In any concentration of thousands of people some are bound to turn to violence as a solution to economic problems. In New York City in 1914 there were reported in the papers 60 murders committed by Italians during the first 8 months of the year, including two policemen. Many if not most of the assaults were Italian-upon-Italian. Rarely did the violence spread into the other ethnic neighborhoods or into the Anglo-American sections of the city. But the impression had been made and sunk deep into the minds of concerned New Yorkers. Thus the Italian was singled out for particular abuse as a criminal. Just as the Jew was stereotyped as a “shylock” and the Irish as a “drunk” so the Italian was stereotyped as the “genuine Italian bandit, black eyed and swarthy, and wicked . . . with rings in his ears . . .”[3]

It is conceivable that anti-Italian sentiments were first spawned in the violence associated with labor agitation and in the turmoil which swept the country after the Haymarket Riot in 1877. After that incident the immigrant, especially the Italian, was visualized as a lawless, disorderly striker. In 1909, six hundred Italian workers struck at West Point because they were refused entry through the main gates and roads leading to the academy. In 1910 a strike against Chicago’s clothing manufacturers found some 10,000 Italians among the 40,000 strikers. In 1912 the great Lawrence textile strike was led by knife-wielding Sicilians. Italians played a key role in the founding of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America.

Yet they were not always on the side of labor although recent studies by Edwin Fenton and Rudolph Vecoli indicated that Italians participated actively in those unions which had the most bargaining power.[4] They were motivated by simple economic factors rather than conventional appeals to solidarity. Indeed Italians were so active in the Journeyman’s Tailor’s Union that they aroused the hostility of the Jewish and Bohemians whose leadership they threatened.

In 1907 the Dillingham Commission reported that “strike after strike in Pennsylvania coalfields in the 1870’s and 1880’s were smashed when employers brought in Slavic, Hungarian and Italian labor.” Without a doubt Poles, Blacks and Italians were frequently employed as strikebreakers and in this capacity incurred the wrath of the unemployed workers, frequently Anglo-American and Irish Americans. In 1874 mine owners in the Armstrong Coal Works in Pennsylvania brought in a group of Italian strikebreakers, as was the case more than a decade later in the Pennsylvania strikes of 1887-1888. In 1887 Italians defeated a longshoremen’s strike and in 1904 a Chicago meatpackers’ strike. An Irish laborer in a textile factory complained about “these dagos who come to this country and takes the vittles right out of our mouths by workin’ for nothing and only wants more money to send home to Italy.”[5]

One author had gone so far as to state that most Italians were so dependent upon the padrone who furnished the jobs and the transpcrtation that they unwittingly were sent to struck plants! For whatever motives, innocent or otherwise, Italians soon found themselves facing hostility in the labor marketplace, a hostility which would increase yearly as with more immigration, cheaper wages were offered and accepted by these contadini.

But the most lasting and vicious image created in America is the Italian-as-criminal myth which is still part of the American perception of the Italo-American. In 1970 one Hugh Mulligan was charged with being a key figure in New York’s organized crime operations which had attempted to corrupt the city’s police force. When he was indicted a spokesman for the Manhattan District Attorney’s office was questioned as to how such a figure could have gone unnoticed for so long. The official replied, “We never really heard about him before two years ago. When we went after organized crime we only went after Italians.”[6] The U.S. Senate Commission on Organized Crime immediately responded with a disclaimer describing organized crime as having no racial or ethnic exclusiveness. Soon after this revelation, the terms Cosa Nostra and Mafia were dropped in favor of such anemic terms as Organized Crime or the Syndicate.

Closer to home, a November 1976 letter to the Cleveland Plain Dealer revealed the fear which Clevelanders still seem to live with. The letter questioned the integrity of the presidential candidates who, amidst campaign promises and speeches, hadn’t said anything about trying “to rid our country of the dreaded MAFIA.” In the January issue of Cleveland Magazine the following headline was printed: “Da Besta Things in Life are Righta Here in . . .” The story which followed was on Mayor Perk’s defense that “there is no organized crime in Cleveland.” The “dreaded Mafia,” organized crime, Italians. A neat bundle of phobias and cultural differences which Americans in general have not yet figured out but continue to use indiscriminately.

Violence against Italians

The spectre of the Italian criminal has deep roots in American culture. Three major events, receiving national attention, confirmed to many Americans their worst fears and misgivings about the southern immigrant. The first incident was the murder of the Police Chief of New Orleans David C. Hennessy in 1890 as he was about to reveal the names of several mafiosi in the city. Fourteen Italians were arrested, nine were tried and six acquitted while a hung jury rendered no decision on the remaining three. All fourteen remained in jail however. Three of them were Italian citizens while eight others were naturalized Americans or in the process of becoming naturalized. One of the fourteen was a teenage boy.

Outraged by the decision and certain of their guilt, a mob of several thousand citizens broke into the jailhouse on March 12, 1891 and shot to death ten of the Italian inmates. While a crowd gathered outside another Italian who had been wounded was dragged outside, hanged, and shot by some twenty vigilantes. Ironically, the man, Polize, was insane and had nothing whatsoever to do with the crime. A grand jury later retroactively justified the murders of the eleven men.

Reaction to the events of March 12th evidenced a decidedly anti-Italian bias. Henry Cabot Lodge wrote that “such acts as the killing of these eleven Italians do not spring from nothing without reason or provocation . . . lawlessness and bloodshed . . . come from the quality of certain classes of immigrants of all races. If we permit the classes which furnish materials for these societies (the Mafia) to come freely into this country we shall have these outrages to deal with . . .”[7]

Protests against the murders came from the Italian government, and President Harrison denounced the killings. Congress later awarded $25,000 to the families of the three Italian citizens but for the other eight Americans or those in the process of becoming Americans no compensation was given.

The New York Times was hardly ambiguous in its position on the matter. The Times first condemned the Italian government for the audacity to demand compensation of any kind since it was “well known” that the government had long used America as a dumping ground for her “Italian outlaws.” As to the matter of New Orleans the Times opened in a similar manner:[8]

These sneaking and cowardly Sicilians, the descendants of bandits and assassins, who have transported to this country the lawless passions, the cutthroat passions and the oathbound societies of their native country, are to us a pest without mitigation. Lynch law was the only recourse open to the people of New Orleans.

In Chicago, where a sizable Sicilian community had been established, the obvious connection between that group and the Mafia was established. “Murder is the foundation stone of the social fabric in Sicily . . . In any community of Sicilian immigrants in America, whenever one man is able to bully and levy blackmail on the rest, that man is Capo Mafia . . .”[9] A “mafia conspiracy” had begun in America and the Italian American population was on trial.

The fear created by the thought of an organized conspiracy of Italian Mafiosi gave way to other forms of hysteria and violence. In 1888 the Buffalo Superintendent of Police ordered the arrest of virtually the entire Italian population of that city following the knifing of an Italian by another. Of 325 Italians arrested two were charged with possessing a weapon. Four years earlier in Altoona, Pennsylvania, some 200 Italians had been deported on suspected criminal charges. In Denver, Colorado, an Italian was lynched in 1895 after being acquitted in a murder trial. In 1908 a crazed Italian anarchist shot a German-born Catholic priest during mass in Denver and once again a wave of distrust swept over the Italians, especially those who were involved with “foreign” political philosophies.

The question is rarely asked if there was in fact a basis for this fear of an Italian criminal conspiracy in the United States. Certainly there was an abundance of intra-ethnic feuding which did lead to outbreaks of violence, knifings and murders. And when a community has experienced acts of lawlessness within its own boundaries by a particular group and later learns that other communities have had similar acts, it is natural to connect these nonrelated acts in a “conspiracy.” When an incident takes on national significance, such as that of the New Orleans lynchings, the fear is heightened.

There is also the charge of inter-ethnic feuding between an established group and these who have arrived more recently. Superintendent Hennessey in New Orleans was Irish, as was Captain Kilroy who led the raids against the “dagos” in Buffalo. The following report compiled in 1910 with the assistance of the New York City Police Department, then largely Hibernacized, also points out that Italians were notorious for their criminality. And yet the conclusions reached by this Immigration Report on “Immigration and Crime” were quite interesting. Some conclusions were as follows:[10]

In New York State Italians had the highest percentage of violent personal offenses but in Chicago, Lithuanians and Slavonians had earned that distinction.

Italians ranked first in Abduction and Kidnapping in New York State. In Chicago Greeks took the lead in that crime.

The conclusion which one could reach would be that in New York State, which had a decidedly heavy Italian concentration, major crimes were more often than not committed by Italians. In Chicago, where the influx of east Europeans had dominated the foreign-born population, their representation in criminality was also higher relative to the population. That was not, however, the conclusion reached by the Immigration Report.

It concluded that Italians with criminal records were flocking to America. It supported this contention with “popular opinion voiced by the press” and “the great assistance displayed by the New York City police department in tracing Italian criminals in New York.” Therefore, Italians were criminal because the police and the press said that they were! If all roads led to Rome, likewise all avenues of criminality led to the Italian and to his criminal conspiracy.

The second incident which re-activated latent anti-Italian hostility took place in 1909 in Palermo, Sicily. Lieutenant Joseph Petrosino, an Italian-American member of the New York City police department, was traveling through Italy in search of information dealing with exconvicts who had migrated to America. He was assassinated in Palermo, the obvious work of the Black Hand. This event convinced the American Press that there was a monolithic conspiracy of crime which spanned the Atlantic and linked Italy with America. The Times reported on March 16, 1909, that Inspector McCafferty of the New York Police Department was expected “to uncover here the beginnings of the plot that had claimed as a victim one of his most valuable men 4000 miles away.”

Richard Gambino, an Italian American author of Blood of My Blood, has rendered some interesting insights into the murder of Petrosino. His explanation is steeped in the aura of a Sicilian oathbound society, of an honor code which had been violated by the presence of a despised police officer, an insult to all Sicilians. The return of a native-born Italian to investigate other Italians was an affront to their honor. It was not a murder, but rather an execution, a defense of an immoral deed against the “via vecchia” of Sicilian life.

It is an interesting explanation but a poor defense for a murder, if that was the author’s intention. The existence in Sicily of a secret society based on extortion, murder and “religiously” followed ritual in dealing with friends and enemies, family and government, can not be disputed. In Calabria, Naples and western Sicily the work of these “honored societies” has been prosecuted by the early Italian government, the fascist regime and the present government. The criminals have operated under titles such as “giovanotti onorati,” “onorata società,” and “Ndrangheta” as it was called in Calabria, the “brotherhood.” After 1860 most of these larger bands had broken up and operated on a local scale, still maintaining a semblance of authority over the poverty-stricken population. In Naples the Camorra specialized in murder, blackmail, torture and disfigurement of victims. In 1877 the Italian government launched an all-out effort to eliminate these associazioni in southern Italy and Sicily. Collectively all of these groups were known in Sicily at least as Mafie, hence the wide use of the term Mafia.

With the influx of southern Italians to America, a certain number of petty hoodlums certainly filed in with the mass of immigrants. In the Italian ghettos there were extortionists operating under the collective name of la Mano Nera, the Black Hand. Yet their status was clearly understood by the residents living in the cities as indicated by the words used to describe such individuals: delinquente (criminal), lazzarone (bum), carogna (scoundrel, louse), disgraziato (evil wretch or slob). These were petty criminals and would have been viewed as such in any society. Unfortunately the link was made between these non-aligned groups of petty criminals and the “onorata società” in Italy. The Sicilian mafia, it was suspected, had been transplanted to America and had taken root. Thus every crime involving Italians was assumed to involve the Mafia. From that to the belief that the Mafia controlled all “organized” crime was but a short step. The Italian had brought the plague of criminality to America and had begun to spread it among the pristine inhabitants of New York, Chicago, Buffalo and Philadelphia. As Police Inspector McCafferty of the New York Police Department stated, the murder of Lieutenant Petrosino had its origins in New York City. The police were quick to respond with mass arrests of Italians. In Hoboken, New Jersey, relations were so tense that when in May of 1909, two police arrived at the scene of an accident involving two Italians, a riot broke out. In December of 1910, fear of the Black Hand led the American Civic League to begin a drive to “free New York City from a large number of Italian criminals and to prevent the immigration of Italian criminals in the future.”[11]

In Chicago a group of concerned Italians formed the White Hand Society to combat the notoriety of the Black Hand and to stem the waves of public sentiment against Italians. It was a dismal failure. Instead, a concerted effort was mounting to stop the continued arrival of Italians in general and particularly those “excitable, superstitious and revengeful” Sicilians.

Sacco and Vanzetti

The following poem was published in Publicmagazine in June of 1919. It indicates a third source of anti-Italian sentiment, the image of the Italian as a radical anarchist:[12]

I mustn’t call you “mickey” and you

musn’t call me “WOP” for

Uncle Sammy says it’s wrong and hints we

ought to stop

But don’t you fret, there’s still one name

that I’m allowed to speak

So when I disagree with you I’ll call you BOLSHEVIK

It’s a scream and it’s a shriek, it’s a

rapid fire response to any heresy you squeak

From 1918 onward it seemed that the Italian mafioso would be eclipsed by the figure of the Italian anarchist. This dual image of the Italian as the lawless and radical immigrant was to have its most sordid reflection in the case of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in the 1920’s. It is interesting to note that prior to the murder trial involving these two men there was an increased association of Italians with radical politics. Indeed, one writer for the Saturday Evening Post reported that in one month alone in 1920 almost 20% of the Italians who applied for visas to America were turned down because they had served jail sentences, were morally unfit, “or because they were Bolshevik agitators.”

In truth the “Red Scare” did have an appreciable number of Italians to point at. In June of 1919 an Italian anarchist, Carlo Valdinoce, blew himself up trying to bomb the home of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. The lawns of Palmer and of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt were showered with pink leaflets promoting a “class war.” The leaflets were traced to an Italian printer in Brooklyn, one Roberto Elia, and his printer, Andrea Salsedo. On Palmer’s orders, dozens of Italian “anarchists” were rounded up and deported. Salsedo was repeatedly beaten by the FBI, became depressed and finally jumped out of the 14th floor window of the FBI headquarters in New York City.

On December 24, 1919, two payroll guards in South Braintree, Massachusetts, were murdered by five “foreigners” during a robbery attempt. Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested as the murderers. Both were carrying weapons, both were aliens and both were self-proclaimed anarchists. In 1921 they stood trial before Judge Webster Thayer who listened while twenty Italian witnesses swore under oath that Vanzetti was in Plymouth delivering eels to the Italian community on that Christmas Eve. As was their Catholic custom these people had fasted on the day before Christmas and traditionally ate boiled and then marinated eels on Christmas eve. Thus their recollection of Vanzetti’s presence was clear.

Italian witnesses were called and dismissed, humiliated and heckled by the prosecuting attorney, Frederick Katzmann. The defense attorney, Herbert B. Ehrmann, concluded that the trial in Plymouth furnished “an excellent casebook for a study in prejudice.”

Had Vanzetti been delivering turkeys to the Anglo-American community in Plymouth that day there would not have been a conviction on the evidence submitted. Had Vanzetti or Sacco spoken English better there would likely have been a different outcome.

Indeed their unorthodox political views helped to condemn them. The fact that they were Italians also sealed their fate, or so they believed. “I am suffering because I am a radical and indeed I am a radical. I have suffered because I was an Italian and indeed I am an Italian.”[13] So thought Bartolmeo Vanzetti. As anarchists they were outside the mainstream of American thought. They were tried primarily for their political views and their ethnic associations and secondly for their alleged crime. Despite appeals and stays of execution they were electrocuted on August 23, 1927.

Michael Musmanno, a defense lawyer called upon during the latter stages of the case, confirmed the anti-Italian bias of some of the key figures in the trial. The foreman of the jury, Harry Ripley, constantly referred to Italians as “dagos” while remarking that if “he had the power he would keep them out of the country.” Before the trial began he had remarked about the defendants, “Damn them, they ought to hang anyway.”[14] Judge Thayer, off the bench, called Sacco and Vanzetti “anarchist bastards” and said he would “get them good and proper.”

An Italian fish peddler and shoemaker who were aware of their different political beliefs and their nationality aroused this country’s and world opinion. The feeling was that they would never have been convicted if they had not been “pick and shovel” men, part of the powerless mass of American immigrant labor. Ben Shahn’s painting, The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti, is itself a moving painting recalling the travail of these two men. Edna Saint Vincent Millay based her poem “Wine from these Grapes” on the plight of the executed anarchists, while Albert Einstein, George Bernard Shaw, John Dos Passos, and Felix Frankfurter protested the verdict, but in vain.

Perhaps the most profound appeal was made by Vanzetti during the closing moments of the trial. As Judge Thayer was passing the death sentence on Nicola Sacco, Vanzetti spoke up. The judge continued to prescribe that “the punishment of death by a passage of a current of electricity through your body” should be inflicted. Vanzetti was not permitted to make his statement so he wrote down the following lines about his friend and their fate:[15]

But Sacco’s name will live in the hearts of the people and in their gratitude when Katzmann’s and (your) bones will be dispersed by time, when your name, his name, your laws, institutions and your false gods are but a dim remembrance of a cursed past . . . in which man was wolf to man.

The Quota System and U.S. Immigration Policy

Crime, anarchy, increasing numbers of southern and eastern Europeans — all this was disconcerting to the American public in the 1920’s. In the popular mind this composite of ignorant and illiterate peasants, paupers and criminals, mingled with other assorted “riffraff,” caused great concern. Add to this the alleged fecundity of Italian immigrants and a racial problem was brewing. Carl Wittke observed in his We Who Build America this fear emanating from supposedly intelligent scholars of population growth, who pointed out:[16]

What disasterous results awaited a country in which 50 Roumanian or Italian peasants would have a perfect army of offsprings in several generations, whereas the stock of 50 Harvard or Yale men would probably be extinct within the same length of time.

Adding to this concern was the perception that the Italians tended to come to America as temporary residents, in droves of males rather than as family units. These “birds of passage” infuriated native Americans. If these Italians were not interested in staying in this country, so ran the argument, they should be kept out permanently.

Thus legislation was adopted to achieve restricted immigration. In 1921 the first Quota Act was established, permitting a total of only 357,803 immigrants from all countries. About 200,000 were allotted to northern and western European countries. Italy was permitted some 42,057 immigrants, a figure which still gave Italy a rather favorable position. But by 1924 certain currents of “racial purity” were much in evidence in America while the concept of the “melting pot” was considered a fallacious and dangerous belief. The immigrant could not and would not assimilate, and continued participation by some countries, notably Italy, would only lead to a case of “alien indigestion.” America should immediately be taken off her “diet” of southern and eastern Europeans.

Accordingly, on May 26, 1924, a new Immigration Act was passed which used a 2% quota based on the year 1890 instead of 1910 as the determining factor. The 1910 census reported that 215,537 Italians had entered this country; in 1890 only 52,003 had arrived. Under the 1924 formula 140,999 permits were issued to northern and western European countries and only 20,423 to southern and eastern European nations.[17] Italy was permitted a total of 3,845 immigrants per year! A cursory look at a yearly report from the United States Immigration Office from 1924 onward reveals that this quota was never inforced; there was an average immigration of at least 10,000 Italians per year. Still, Italian immigration was successfully reduced to a figure which would no longer pose a “threat” to the American population and which would maintain “racial purity” within the United States.

This quota act remained basically the same until 1963 when John F. Kennedy urged a new and more positive immigration policy. His ideas were concretely expressed by President Johnson with the passage of a new immigration act on September 30, 1965. It raised the number of immigrants from any single country to 20,000 per year based on technical skills and domestic demand for those skills.

Legal restrictions on Italians opened the way for various forms of overt discrimination. The prevalence of a Darwinian mentality in the United States singled out almost every ethnic and racial group for unfair, capricious scrutiny. For example, an article entitled “Mental Tests for Immigrants” appeared in the North American Review in 1922. It ranked 16 ethnic groups according to their relative intelligence and asserting that while the English, Germans, Dutch and Swedes ranked remarkably high in mental ability, Italians and Poles were consistently low in aptitude and intelligence, physically developed but emotionally unstable.[18] Mr. Sweeny, the author of this piece, passionately concluded that “we have no place in this country for the man with the hoe, stained with the earth he digs, and guided by a mind scarcely superior to the ox whose brother he is.”

Madison Grant, scientific dilettante and founder and chairman of the New York Zoological Society, was one of the most strident Anglo-Saxon superracists. His “classic” of genetic scholarship, The Passing of the Great Race, revealed his fear of the “Mediterranean Race” whose physical characteristics certainly would mongrelize the American population. “It is race, always race,” he wrote in 1918, “that sets the limit (on stature). The tall Scot and the dwarfed Sardinian owe their respective size not to oatmeal or to olive oil . . . The Mediterranean race is everywhere marked by a relatively short stature . . . and also by a comparatively light framework and feeble muscular development.” The Mediterraneans who were threatening America would soon extinguish the “old stock” Nordics unless the latter reasserted themselves and shut out the undesirables.

Condemnation of Italians for their small stature continued during and after World War I. Kenneth Roberts, famous as a frequent contributor to the Saturday Evening Post and his many fictional accounts of colonial America, called southern Europeans a “hybrid race of good for nothing MONGRELS . . .” Italian intelligence was questioned in numerous periodicals. Typical are the comments of Professor Edward A. Ross, who stated that Italians ranked lowest in the ability to speak English, lowest in proportion naturalized after ten years’ residence, lowest in proportion of children in school, highest in proportion of children at work. “Steerage passengers from a Naples boat show a distressing frequency of low foreheads, open mouths, weak chins, poor features, small or knobby crania and backless heads!”[19] All this in America less than twenty years before Hitler and his ideology formed the Third Reich.

The president of Stanford University, David Starr Jordan, was reprinted in the Congressional Record regarding his opposition to the “Biologically Incapable” southern Italians. In part his statement reads: “. . . There is not one in a thousand from Naples or Sicily that is not a burden on America. Our social perils do not arise from the rapacity of the strong, but from the incapacity of the hereditarily weak.” Woodrow Wilson’s five-volume History of the United States treated Italians in much the same way, finding them with “neither skill nor energy nor any initiative of quick intelligence . . .” He added that the “Chinese are more to be desired, as workmen, if not as citizens, than most of the coarse crew that comes crowding in every year at the eastern ports.” Wilson did not go as far as another Nativist writer who referred to the “coarse” crews coming from Italy as “steerage slime.”

The Catholic Church and the Children of Columbus

If Italians were demeaned, insulted and humiliated by the insensitive institutions representing native Americans they still retained a sense of commonality with other ethnic groups by their membership in the Catholic Church. But this bond was a superficial and weak one at best, for soon Protestants and fellow Catholics were critical of the Italian “brand” of Catholicism.

To be sure, Italian Catholicism has been and continues to be a blend of orthodox religious fervor and superstition, with a very close and personal belief in the efficacy of the sacramental church and the veneration of the hierarchy of the saints. One historian of Italian social patterns, Leonard Covello, even concludes that in the Mezzogiorno the Catholic Church did not have a very great influence over the social and moral lives of the people. Despite being nominally Catholic, despite their alliances with particular saints and their enthusiasm for saint’s days, their religion was a mixture of superstition, faith and ritual. Along with the rituals imported from Italy was the inbred distrust of the power of the clergy in particular and of the Papacy in general. Just as the Church had been viewed by Italians as the opponent of the Risorgimento, the adversary of progress, of the awareness of one’s own rights, so this attitude was transmitted to the New World.

In the old world things were different. You gave one of your sons to the church to be made into a priest. This was economically astute, for a son could help the family as a priest. In America every pair of hands meant extra money for the family. In America children best served the family by their roles in a secular society. In Italy religion was often a pragmatic affair where saints were honored to the extent that they seemed to answer the requests of the suppliant. When they did not perform correctly their images would be humiliated, stoned, beaten and generally ignored whenever the desired services were not rendered.

This attitude toward the Church increased as the immigrant confronted a native Catholic hierarchy in America, a church which saw its role as the promoter of the “melting pot” concept of assimilation. As Bishop Dunne stated in 1923, “One thing is certain. The Catholic Church is best qualified to weld into one democratic brotherhood, one great American citizenship, the children of various climes, temperaments and conditions.”[20] Very soon this process of forced conformity to a church which was more American and Irish than Catholic would amount to a direct assault upon the values and cultural heritage of the Italian immigrant.

Italians were viewed as “different” Catholics and the Irish-and-German-dominated American clergy was vocal in pointing out this distinction. As late as 1917 the Archbishop of New York, Cardinal Farley, was advised by Reverend B.J. Reilly that:[21]

The Italians are not a sensitive people like our own. When they are told that they are about the worst Catholics that ever came to this country they don’t resent it or deny it.

There was always the questioning of loyalty to the faith, the imputation of a lack of Catholic respectability. The Italians, it was claimed, were shameless in their poverty. Worse, many were defectors from Catholicism, willing recruits to evangelical Protestantism. But as one writer viewed the situation, it was not a loss to the Church. Writing in the Catholic magazine America in 1914, Thomas F. Coakley concludes that:[22]

It is unfair to count as lost to the Church several millions of immigrants from Southern Europe for the simple reason that they did not belong to the Church in a real sense when they landed on our shores . . . and they do not know what loyalty to the Church means intellectually, financially, or morally.

The Protestant evangelist regarded the conversion of Italians as a possible first step in civilizing them and bridging the cultural gap between the Nordic and the Latin.[23] The immigrant would become Americanized and Christianized at the same time and could then look upon the Protestant ethic of social and economic success as a mark of God’s favor. Although some Italians did convert, the process was not a successful endeavor by America’s Protestant leaders.

For many Italians their first perception of American Catholicism came from a service in the basement of an Irish church. In some cases the Italian members quickly flooded the Irish parishes. At St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral on the New York’s lower east side, the parish was totally Irish following the civil war. By 1882 the church had to conduct services in the basement in Italian on holidays and special feast days. Within eight years over 5000 children of Italian parents were baptized in that basement. By 1909 over 2500 children in their school were Italian and the Irish began to move out of the parish.

Polite warnings led to open hostilities between these “children of the church.” Irish priests spied on Italian clerics, reporting to the Archbishop infractions that were the result of “catering” to the whims of the Italian parishioners. Italian priests explained to the Archbishop their own feelings on attending an Italian church and the impact that a singular ethnic parish would have on the Italian community:[24]

Given an Italian church with services in the Italian language, our people would not be so negligent in the observance of their religious duties. They are for the most part very poor and feel ashamed to attend the American church which they can not even understand and which does not appeal to them anyway . . .

By 1925 Italian parishes had begun to develop and achieve autonomous status in various parts of this country. By 1918 the Catholic Directory listed the existence of about 580 Italian churches and chapels for an Italian population of about 3 million. Churches became the symbol of many ethnic communities. It was the ethnic parish which held together the basic structure of the old world and introduced the new ways of America.

The men and women who served these Italian parishes would deserve a book of their own. From the scattered work of the early supportive missionaries a growing concern for Italian priests and sisters culminated in the efforts of Bishop Scalabrini of Piacenza. In 1887 he founded the Congregation of the Missionaries of St. Charles to operate Italian churches in the United States. Mother Francesca Xavier Cabrini became the first American citizen to be elevated to sainthood, and was one of the first sent by Bishop Scalabrini.

Mother Cabrini arrived in New York City in 1889 with six nuns. She met with Archbishop Corrigan, who suggested that she return to Italy. Persistent in her desire to remain in America, she was permitted to teach Italian children at St. Joachin’s Church near Mulberry Street. From this humble beginning she and her order established other orphanages, hospitals and schools in New York and New Orleans. She died in Chicago in 1917 and was canonized in 1946 by Pope Pius XII as the “Saint of the Immigrants.”

In recent years some Italian-Americans have felt discriminated against in regard to their representation within the hierarchy of the American Catholic Church. They cite statistics to justify their contention that the Church has been biased in favor of Irish and Germans prelates to the exclusion of Italo-Americans. For example, as late as 1950 not one bishop of Italian descent was evident out of more than 100 Roman Catholic bishops.

Figures provided by Andrew F. Rolle tend to spotlight this obvious discrepancy. In 1972 some 57% of America’s bishops were of Irish extraction while only about 17% of American Catholics were Irish. In 1972 only nine bishops were of Italian descent even though almost 12,000,000 Americans are identified as Italo-Americans. He concludes that while Italian-Americans are advancing in all other fields their ascent within the American Catholic Church has seemingly been blocked.[25]

Monsignor Geno Baroni, head of the National Center for Urban Ethnic Affairs, commented on this situation in 1971. He blamed the Church for her over-emphasis on assimilation into the American culture at the expense of the loss of her traditional heritage. “Someday some Italian-American priest is going to write a book about Mother Church, and it’s going to make Portnoy’s Complaint look like nothing.”[26] Monsignor Baroni’s remarks are indicative of a growing concern among Italian-Americans that only through ethnic diversity can they truly remain good Catholics and fully participate in the functioning of the Church.

I think that the problem of non-representation within the Catholic hierarchy in America may be explained not only by the obvious lack of Italians as bishops, archbishops and cardinals but also by the single most important cause of this numerical deficiency. It lies within the mentality of Italian-Americans in regard to their church. The facts are simple enough to explain while the attitudes which have created present conditions are more complex to decipher.

In the first place some anti-Italian bias within the American Church must certainly not be ruled out; but it should not be given priority in explaining the lack of Italian-American bishops. The cold reality of the situation is that Italo-Americans are not becoming priests. Regardless of the number of Italians who are nominally Catholic, this figure becomes meaningless unless a percentage of that figure has chosen the vocation of the priesthood. But statistics point in another direction. In 1973 there were 58,161 priests in the United States, 12% of whom were Italian. This figure includes all foreign-born priests, so that the number would tend to be inflated. In 1973 there were 34 American archbishops, one of whom was an Italian. There were also 253 bishops, five of whom were of Italian ancestry.

Religious attitudes in the decision-making process among Italian Catholics is also a major factor to be considered. Father Andrew M. Greeley, Director of the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago, has done extensive research on attitudes among ethnic groups which has revealed some interesting points about Italians nominally involved with the Church. He found that “Italians are the least pious of all Catholic groups,” with only 13% of Italians scoring “high” on piety as compared to 32% of Irish, 31% of German and 30% of Polish Catholics.[27] Greeley also discovered that while 46% of Irish and 50% of German Catholics belong to at least one religious organization, only 22% of the Italians were affiliated with any such organization. Finally on church attendance only 30% of Italian-American Catholics considered church attendance important while 72% of the Irish and 56% of the German Catholics thought that regular attendance was important.

When interest in the process is focused mainly on positions of prestige rather than the day-to-day functioning of the institution, the cry of discrimination has little validity. If Irish and Italians clash over the predominance of one group within the Church’s hierarchy, the fact remains that the Irish Catholic has supported his Church on a more continuous basis than his Italian counterpart. Perhaps the future will see a lessening of the traditional Italian philosophy that the church is cosa femminile, a woman’s thing, and offer more involvement on the part of the entire Italian American community.

Some studies indicate that ethnic participation in the Church’s hierarchy among Italians is not as important as it was at one time. It is no longer a burning issue that the parish priest, for example, be Italian. On the Sabbath the majority of Italians now join with Polish, German and Irish Catholics in their suburban parishes. The melting pot concept seems to be working effectively in the churches of America. As Glazer and Moynihan have contended, “The Irish and Italians, who often contended with each other in the city, may work together and with other groups in the Church in the suburbs and their separate ethnic identities are gradually muted in the common identity of American Catholicism.”[28]

Although this may be the case, the continued Italian tradition of secularism, and of skepticism about the Church, may still have a strong effect in maintaining vestiges of ethnic identity. Superficially, religious beliefs may not vary between Irish, Polish and Italian Catholics but there still are discernable fundamental disagreements if at least one study is to be considered. In 1965 a national survey indicated that only 37% of the wives from an Irish Catholic background used some form of artificial birth control and thereby flouted the Church’s Magisterium on the subject. In contrast 68% of the wives of Italian background used birth control.[29] The conclusion reached by Potvin and others conducting the survey was that there still was a higher degree of independence in the attitude of Italian wives toward one of the Church’s most controversial doctrines.

As long as Roman Catholics of Italian extraction continue to pursue religious practices and hold beliefs which are contrary to the basic teachings of the Church, it is to be expected that more intimate representation on the hierarchy in America will not be forthcoming. If today’s Italian-Americans do not feel part of the Church, they should not lay the blame on discrimination. The question may be one of self-imposed exile, a condition which Italian-Americans themselves have helped to create.

World War II

The period between the world wars witnessed an odd phenomenon relative to Italian Americans and the rise of Fascism in Italy. While the immigrant still bore the brunt of insults and discriminatory policies within the United States, many of their vilifiers applauded the efforts of Mussolini and his Blackshirts against the forces of “bolshevism” in Italy. Indeed, Italo-Americans were afforded the opportunity to rekindle a sense of ethnic pride by supporting Il Duce and his antics during the 30’s.

Ironically, those Italian immigrants and exiles who did not favor fascism in Italy were labeled Communists and again subjected to attack from the nativist press. However, America’s brief flirtation with Mussolini ended abruptly in the mid-1930’s. Italo-Americans faced the dilemma of either continuing to support fascism and risking charges of disloyalty to America, or joining the opposition to fascism and being associated with communism.

At the outset of World War II, Italian-Americans, like Japanese-and German-Americans, were in a precarious position. From the pen of the columnist Westbrook Pegler came invectives against any retention of ethnic identity. With respect to Italian-Americans he was especially vicious, at one point writing that “The Americans of Italian birth or blood have no reason to love Italy,” where “extortion and terrorism” was a native peculiarity . . . as characteristic as garlic.” As to the value of Italian-Americans in this country he was again explicit: “As to Italy’s contribution to this country I have always been skeptical . . . Italy got rid of alot of excess people and the United States gave the immigrants a chance in life.”[30]

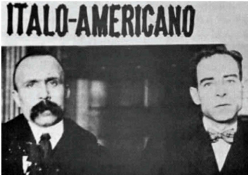

At one point he characterized Generoso Pope, the publisher of Il Progresso Italo-Americano as a “handkerchief immigrant” who had too much influence over Italian-Americans. His papers tended to make Italo-Americans feel “self conscious, to segregate them from other Americans both socially and politically . . .” and created a “national minority with a persecution complex.”[31] It should be stated that Pope was originally an outspoken defender of Mussolini at the beginning of his regime but ended his defense of fascism after 1935. During the war he personally sold more than $49,000,000 worth of war bonds and was chairman of the committee for Italian-Americans of New York State. His patriotism was indisputable and he was personally lauded in the Senate for his efforts. This, then, was the “handkerchief immigrant” to whom Mr. Pegler referred.

In reading the remarks of Pegler one can understand and sympathize to a degree with the unspoken fears which may have motivated him to write his invectives. It is quite another matter to read the scurrilous remarks printed in the Congressional Record in 1945 by the Honorable Theodore G. Bilbo, U.S. Senator from Mississippi. In a letter to the Senator, Mrs. Josephine Piccolo criticized him for not voting in favor of a bill and actually filibustering against it. She concluded her three-paragraph letter in the following manner: “We want the FEPC and you must help us get it, or you will answer to the millions of Americans who want it.” Emphatic perhaps, but certainly within the rights of an American citizen.

The Senator requested that the letter along with his reply to Mrs. Piccolo be printed in the Congressional Record. In part his reply reads as follows: “My Dear Dago: (If I am mistaken in this please correct me.)” Toward the end of this letter he advised Mrs. Piccolo to keep her “dirty proboscis out of the other 47 states, especially the dear old State of Mississippi.”

When Congressman Vito Marcantonio of New York read the exchange he demanded that Bilbo apologize for his lack of manners, reminding the Senator that three of Mrs. Piccolo’s brothers were in the American armed forces and that one had been killed in action. Bilbo took on the Congressman with equal grace and style. He accused Marcantonio of associating with gangsters and of being a communist. The New York Congressman was a “notorious political mongrel” who had the audacity to question the ethics of a U.S. Senator “whose every heartbeat synchronizes with the ideals and principles of the founding fathers.”[32]

As a postscript it should be mentioned that although there was some fear that a fifth column of Italian-Americans was forming in this country to support the fascists, no movement appeared. Less than 200 Italian aliens were interred shortly after the outbreak of the war. Whatever sympathies had led to early Italian-American support of fascism had withered by 1935. During the war years no Italian engaged in espionage or sabotage. No Italian-American has ever been tried for treason. During World War I about 400,000 Italian-Americans participated in the war and during World War II almost 1,500,000, or about 10% of the armed services, were of Italian extraction.

Post World War II and Cleveland

In the years since the war the exploits of the Italian-American criminal have been glorified and sold in unforgettable classics such as The Godfather, The Brotherhood, The Mafia is Not an Equal Opportunity Employer, The Valachi Papers, Honor Thy Father and The Godmother. Mafia “witch hunts” in the Senate, led by Kefauver in the 1950’s and by Senator Robert F. Kennedy in 1966, have enriched the American vocabulary with a series of phrases such as “The Kiss of Death,” “Numero Uno,” and “Cosa Nostra.” The vilification of Italians during the television series “The Untouchables” was so bad that members of an Italian service group began to call it “The Italian Hour,” while a sarcastic sophomore at a local university labeled the show “Cops and Wops.”

Michael Novak observed in his The Rise of the Unmeltable Ethnics that a great deal of the bigotry which still exists toward ethnics originates and is perpetuated by that stratum of society known as the “intellectuals.” For a number of reasons he sees a chasm of intellect and sensitivity separating the WASP and the ethnic. He makes an interesting observation on this point midway through his book:[33]

Was Agnew so wrong when he detected “an effete corps of impudent snobs”? Did he anger people by a calumny or by thudding an arrow into the bulls-eye?

This reactionary attitude on the part of some members of the intellectual community has indeed some basis in fact. There is a fear, I think, thinly veiled by a pretended assumption of superiority, of ethnics trying to enter traditionally Anglo-American domain. This mentality of degrading what one fears can be traced back to the racial geneticists such as Grant in the early part of this century.

A concrete example of this kind of arrogance occurred recently at Yale University. Michael Lerner, son of columnist Max Lerner, was a graduate student at Yale during the mayoral elections in New York City involving Mario Proccacino in 1969. He reported a comment made by his professor at Yale regarding Proccacino and Italians. The “scholar” remarked that “If Italians aren’t actually an inferior race, they do the best imitation of one I’ve seen.” Everyone at the table laughed, Lerner recalled; but he suggested that the professor could not have said that about blacks if the subject had been H. Rap Brown.[34]

During the waning months of the 1976 presidential campaign a member of the President’s Cabinet was forced to resign after it was revealed that he had made an obscene and derogatory comment about Black Americans. A month later the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff made a remark about Israel’s military burden upon the United States. He was immediately attacked by various Jewish American organizations and was forced by the president to apologize.

In a culture where a racist term for Blacks is occasionally the cause for justifiable homicide, when insinuations about foreign governments bring about immediate apologies, when employer must tread ever so lightly in reference to gender, with an ever-vigilant eye toward quotas when dealing with “official” minorities, the sobriquets “Wop,” “Dago,” and Mafia are still uttered. As long as the various media treat organized crime as a source of continuous entertainment the terms Mafia and Italian will remain synonymous in the popular mind. As long as Italians are characterized as vicious hoodlums, opera-singing or undershirted buffoons, our culture will continue to alienate a large segment of her most productive citizens.

To be able to laugh at and be amused by our own individual differences and occasional failings lies at the base of our humanity.

To violently oppose the defamation of select groups of “legally sanctioned” ethnic communities while showing benevolent neglect toward scurrilous remarks about others is in itself derogatory and should be condemned. Sadly, this is still the basis of contemporary American culture.

We have become conditioned to laugh at jokes made about ourselves by others. Italian-Americans need to develop another response. Quiet anger, resentment and retreat into insularity were ineffective in the past and would be worse in the future. As one Italian-American author has suggested, we must update our relations with and responses toward the “outside world.” However melodramatic it may sound, the obnoxious image of the Italian as criminal and clown must be confronted and destroyed.

The time has arrived when Italian-Americans should join with other groups and promote a sense of “creative ethnicity.” By this I mean that each group uses its ethnicity as a point of departure for growth in human relations rather than as the final proof of worth. Through this process one learns about one’s own identity and thereby can also appreciate the cultural complexities of other groups.

With the same sense of ethnic awareness a concerted effort should also be made to denounce in as many legally sanctioned forms as possible those channels of communication which continue to portray the “realities” of American life as white-socked east Europeans, spaghetti-slurping Mediterraneans, dozing “frito banditos,” “superfly” blacks, and “hayseed” southerners. When economics are directly involved, cultural bias undergoes immediate changes.

A local example may serve as a case in point. During the urban riots of 1964 it was reported in the Cleveland media that a black activist group, the United Freedom Movement, would picket Murray Hill school the following day. Before pickets actually arrived hundreds of residents from “Little Italy” formed at Mayfield and Murray Hill Roads to prevent any picketing. Due to police and school board intervention, no United Freedom Movement members actually entered “Little Italy,” although some fighting did occur on Euclid Avenue.

That evening the Cleveland Press reported in its headlines “Two Negroes Beaten by Crowd in Murray Hill School Fight.” The publicity given to “Little Italy” was overwhelmingly unfavorable both in the newspapers and on the local radio stations. Italian-Americans from the Greater Cleveland area justifiably felt maligned, especially by the Press and decided to do something about it. They began a massive boycott of the paper with an estimated 20-30,000 Italians cancelling their subscriptions to the paper. After two weeks the Press sent a reporter into the neighborhood to smooth ruffled feathers and to spread the word that the paper would take a more objective stand on the entire emotional issue. The boycott was dropped but the impression was made.[35]

- John Higham, Strangers in the Land (New Jersey: Atheneum Books, 1963) pp. 63ff. ↵

- James W. Vander Zander, American Minority Relations, quoted by Richard Gambino, Blood of My Blood (New York: Doubleday, 1974) pp. 253-254. ↵

- The New York Times, July 9, 1881. ↵

- Edwin Fenton, Immigrants and Unions, A Case Study: Italians and American Labor, 1870-1920. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Harvard University, 1957 and Rudolph J. Vecoli, Chicago's Italians Prior to World War I: A Study of their Social and Economic Adjustment. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Wisconsin, 1963. ↵

- Eric Amfitheatrof, The Children of Columbus (Boston, 1973) p. 174. ↵

- The New York Times, July 24, 1974. ↵

- Henry Cabot Lodge, "Lynch Law and Unrestricted Immigration" in The North American Review, 152 (May, 1891), 602-605. ↵

- The New York Times, March 16-17, 1891. ↵

- Quoted in Luciano Iorizzio and Salvatore Mondello, "The Origins of Italian American Criminality" in Italian Americana, I (Spring, 1975) p. 219. ↵

- Salvatore J. LaGumina, ed., WOP: A Documentary History of Anti-Italian Discrimination in the United States (New York: Straight Arrow Books, 1973) pp. 72ff. ↵

- Iorizzio and Mondello, op. cit., p. 167. ↵

- Edmund Cook, "Bol-She-Veek" in Public, XXII (June 2, 1919) p. 772. ↵

- LaGumina, op. cit., pp. 239-246. ↵

- Michael Musmanno, The Story of the Italians in America (New York, 1974) pp. 143-146. ↵

- Quoted in Herbert B. Ehrmann, The Case That Will Not Die (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1969) p. 459. ↵

- Carl Wittke, We Who Built America (New Jersey: 1939) p. 406. ↵

- Cited by Joseph Lopreato, Italian Americans (New York: 1970) pp. 16ff. ↵

- Arthur Sweeny, "Mental Tests for Immigrants," North American Review, 215 (May 1922) 600-612. ↵

- E. Ross, World's Week, Volume 27, No. 4 (August, 1914) 278-279. ↵

- Silvano M. Tomasi, "The Ethnic Church and the Integration of Italian Immigrants in the United States" in Tomassi, ed., The Italian Experience in the United States (New York: Center for Migration Studies, 1970) pp. 163-193. ↵

- Ibid., p. 167. ↵

- T. R. Coakley, "Is Peter's Bank Leaking?" America, 11, No. 5 (May 16, 1914) 103. ↵

- For an interesting report of evangelical work among the immigrant Italians see Antonio Mangano, Sons of Italy (New York: Missionary Education Movement of the United States and Canada, 1917). ↵

- Cited in Tomassi, "The Ethnic Church" p. 180. ↵

- Andrew Rolle, The American Italians (Belmont, California, 1972) pp. 102-107. ↵

- Ibid., pp. 104-105. ↵

- Andrew M. Greeley, Why Can't They Be Like Us? (New York: The American Jewish Committee, 1969) pp. 46ff. ↵

- Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot (Cambridge: The M.I.T. Press, 1963) p. 204. ↵

- Raymond H. Potvin, Charles F. Westhoff, Norman B. Ryder, "Factors affecting Catholic Wives' Conformity to their Church Magisterium's Position on Birth Control," Journal of Marriage and the Family, 30 (May, 1968) 263-272. ↵

- New York World Telegram, June 4, 1940, June 6, 1940. ↵

- Ibid., December 21, 1940. ↵

- Congressional Record, 79th Congress, 1st Session, p. 7995. ↵

- Michael Novak, The Rise of the Unmeltable Ethnics (New York: The Macmillan Publishing Company, 1973) p. 176. ↵

- Quoted in Novak, Ibid., p. 93. ↵

- This incident was reported to me by a friend who has long been an observer of the local Italian scene. ↵