Part III: The Italian Community of Cleveland

Chapter 7: The Italians of Cleveland: An Introduction

Sources

Cleveland’s Italian community is one of the most colorful and vital of the city’s 60 ethnic groups and has been a favorite topic of area writers. Although one of the most recent groups to immigrate to Cleveland, the Italian population has nevertheless been the subject of several studies over the last half century as well as a series of less extensive but equally important articles.

The first analysis of the city’s Italian population was undertaken by Charles W. Coulter in 1919 under the auspices of the Cleveland Americanization Committee. Entitled The Italians of Cleveland, it was a general survey of the group’s early settling patterns, business, civic and religious leaders as well as a description of their social and fraternal organizations. The forty-three page publication gives little detail but does provide the basic framework on which other works have been based. It can be said that even at this early date Coulter’s research provided the general Cleveland readership with a very favorable impression of her then increasing Italian population.

Coulter’s work seemed to stimulate a few scholarly treatments of particular aspects of Cleveland’s Italians which were generally submitted for advanced degrees at local universities. For example, at Western Reserve University there are found several detailed studies dated in the late 1920’s such as Ruth Van Vookis’ 1929 thesis entitled “A Study of the Italians in the Woodland-East 110th Street District” and William Lewis Bodley’s 1938 thesis on “The use of Southern Italian Cultural Material in Group Work Programs,” again written at Western Reserve University.

Other specialized studies at the graduate level include Pat J. Columbro’s research into the Italians along the Mayfield Road Area in 1948 and Reynold A. Pana’s study of the Southern Italian Immigrant, written at John Carroll University in 1966. All of these studies have had a rather limited exposure beyond the immediate university and normally have been accessible only to graduate students.

Two doctoral dissertations have dealt with Cleveland’s Italians, one of which has been recently published by Harvard University. Charles Ferroni’s 1969 Dissertation at Kent State University deals with “The Italians in Cleveland: A Study in Assimilation.” Dr. Ferroni, currently a professor at Ashland College and Vice President of the Italian-American Historical Society, skillfully arranged a number of personal interviews with prominent Cleveland Italians in recreating the cultural, religious and social service center in Cleveland’s “Little Italy” section along Mayfield Road.

The other dissertation is Josef Barton’s “Immigrants and Social Mobility in an American City” written at the University of Michigan in 1971. This work was published in 1975 by Harvard University Press under the title Peasants and Strangers. Basically Barton’s research concentrates on the social, economic and education mobility of Cleveland’s Italian, Slovak and Rumanian immigrants from 1890 to 1950. More sociological than historical in approach, Dr. Barton finds that the second generation ethnic in Cleveland normally achieved a degree of social mobility equal to that of a native-born American. The 292-page book is complemented by a series of valuable comparative charts on a variety of educational, economic and social topics.

One other collection important to the study of Italian ethnicity within Cleveland is the “Italian Section” of the Cleveland Foreign Language Newspaper Digest, a project of the United States Works Projects Administration in 1939. This collection includes abstracts in translation from Cleveland’s two Italian language papers, L’Araldo and La Voce del Popolo Italiano. Even a cursory reading of this 95-page digest indicates some of the feeling within the Italian community in Cleveland about their settlements, their organizations, their problems and their aspirations. For the non-Italian reader it is an indispensable and highly entertaining source of Italianità.

With the renewed attention given to ethnicity in the past decade several ambitious collections have been produced by members of Cleveland’s academic community at Cleveland State University and John Carroll University. The first, published in 1972 by the Institute for Urban Studies at Cleveland State University is entitled A Report on the Location of Ethnic Groups in Greater Cleveland by Donald Levy. Within Levy’s study are found over 30 different ethnic groups with a brief 2-3 page background sketch of each. Of additional importance are a set of maps indicating approximate location of each group in Cuyahoga County as well as census tract information relative to each group.

Following this Report were several important studies and collections dealing with ethnicity in Cleveland. The collection Ethnic Communities of Cleveland: A Reference Work, edited by Dr. Michael Pap with a bibliography by Dr. George Prpic provides a useful study on several of the local ethnic groups, including the Italians.

Also in 1974 was published the Greater Cleveland Nationalities Directory, a joint effort of the Nationalities Services Center, the Institute for Urban Studies Radio Station WZAK and Sun Newspapers. It is a magnificent and comprehensive guide to over 2000 organizations involved in greater Cleveland’s 60 ethnic groups. For the Italians these are listed major churches, social, and cultural, and professional societies as well as the active leaders within each organization. Especially interesting for students of ethnicity is the listing of over 35 Italian fraternal societies and lodges in Greater Cleveland. It is an impressive work which merits the attention of anyone interested in the multifacited world of Cleveland’s communities.

Another study of scholarly interest is the monograph coauthored by Dr. Karl Bonutti of Cleveland State University and Dr. George Prpic of John Carroll University dealing with Selected Ethnic Communities of Cleveland: A Socio-Economic Study (1974). Using a series of questionaires and interviews, this work analyzes four contemporary ethnic communities, including St. Rocco’s neighborhood along Fulton Road, in terms of numerous aspects of everyday life. Included in this format are age, occupation, ethnic background income, and property ownership, among other items of statistical importance. It is the most detailed analysis of all studies conducted to date on contemporary Italians in Cleveland.

The various studies mentioned, some of which are highly selective, are usually inaccessible to the general public; and despite the resurgence of ethnicity in Cleveland in the last few years, a definitive study of Cleveland’s Italians remains to be written. One reason for this condition lies in approach and methodology. Too many writers have concentrated on the Italian as “hero” and have recited the familiar litany of “important” Italians who made their careers and fortunes in Cleveland. Other authors have become caught up in the ethnic “numbers game” wherein the importance of the group is measured by the number of “influential” members within the economic, cultural or political spectrums. This kind of approach as a primary view of an ethnic group should be avoided at all costs but it will survive because it is the easiest method of historical research.

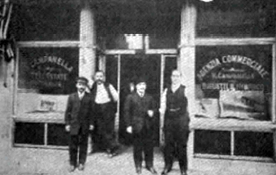

In the major studies of Cleveland’s Italians the question of origins is seldom raised, much less discussed. The rise of the Carabelli or Catalano or Campanella families appears to have occurred through a series of continuous successes. Too often we find the story of an immigrant’s rise from laborer to entrepreneur within a decade after arrival, while the typical process of growth and maturation within the city, beset with failure and setback, is hardly mentioned.

Another factor of Italian ethnicity seldom researched is the basic story of the multitude, those thousands who were not particularly successful in economic endeavors, but who did nevertheless labor and survive in a foreign and often hostile environment. Their festivals, their fraternal organizations and their churches are standard topics of research. But what of the individuals? What occupations did they engage in, what kind of social and economic success did they achieve? How well or how poorly were they received by their adopted city? Finally, what influence did they exercise, and continue to exercise, in Cleveland? These are valid questions which need to be answered before we begin to approach a comprehensive study of the “Italian factor” in Cleveland life. The following essays will at least fill in some of these informational gaps and provide further avenues for research and insight into the Italians of Cleveland.

Early Settlements

In the City of Cleveland’s Annual Reports for 1858 there is recorded the marginal note that three Italians were admitted to the city’s infirmary during that year. This is an interesting statistic, for the 1860 Federal Census makes no mention of Italians whatsoever in the city of Cleveland, while neighboring Cincinnati recorded some 320 Italians. Presumably these three early Italian immigrants were included in the 662 “Others” listed in the census as being part of the foreign-born population of Cleveland.[1] In 1860 there were 10,437 foreign-born immigrants in the city, mostly of German and Irish descent, who made up almost 45% of Cleveland’s population, an extraordinary percentage for that period.

The reality of a growing flood of immigrants to Cleveland did not go unnoticed nor unchallenged by the local media. The Cleveland Leader in November of 1876 editorialized on the expanding foreign migration:[2]

It will be observed that the falling off in the total arrivals for this time is about 25% . . . and it is attributed to the hard times being widely known throughout Europe, both through the letters and reports of the foreigners in this country to their friends and the newspapers and governmental reports. It is, of course, for the interests of the government not to mince their remarks on our difficulties but on the contrary, to exaggerate them as much as possible in order to stop the exodus of their subjects.

There was some cause for alarm, not only because of the swelling population, but about the control of these new immigrants. According to police reports for 1874, some 8563 foreign arrests were made in Cleveland, 1253 of which were designated as having been Irish immigrants. As these foreigners surged through the counting stations at the railroad depots in Cleveland, past the Bureau of Emigrant Police, there was a certain apprehension about these “new people,” especially from southern and eastern Europe. Would they be a burden upon the charitable institutions of the city, a drain on the society of Cleveland, a threat to the peace of the community? Would they accept their new country, learn the language and customs, and fit into this city upon the Cuyahoga?

If these were indeed some of the concerns of Clevelanders, their encounters with and impressions of the Italian immigrant were to be a happy experience. Even though some individuals of Italian descent in Cleveland were involved in crime or were implicated in anti-social behavior, the city’s Italians rarely brought disgrace upon themselves, their city, or their newly adopted country. As a group they had possibly the lowest crime rate for Italians of any major city in the country. Statistically, Cleveland’s Italian population was consistently ranked among the lowest in terms of welfare relief among all groups, native and foreign born. While they gained from their varied experiences and confrontations with America they also shared with their adopted city many of their best and brightest sons and daughters, especially during this formative period.

The 1870 census listed 35 Italians in Cleveland, although this figure could be challenged as a mere estimate. This statement may be made because at least 20 Italian-surnamed individuals could be found in the Cleveland City Directory for the years 1864-65. Included are the names of professional and skilled men such as Joseph Agricola, a carpenter; Nicholas Bruno, a bookkeeper; Joseph Durgetto, a gardener; and the Climo brothers who were laborers. In the 1870 census 29 of the 35 Italians were shown as being engaged in some form of employment such as tradesmen, mining and manufacturing, steelwork and bootmaking. Fifteen of the men were listed as stone masons, probably as part of the group with James Broggini from Lombardy. The Italian immigrant who came to Cleveland during the post-Civil War period usually had a skill or trade to develop in the city. Regardless of their initial work experience the early Italians believed in the work ethic, that honest labor ultimately produced success. Two early Italian experiences in the city can best illustrate this point.

Joseph Agricola was listed in the 1864 City Directory as a skilled laborer, a carpenter. Ten years later Agricola had moved from his original job to that of insurance salesman and by 1880 is recorded as being a solicitor living on Vine Street.[3]

A much more intriguing story is that of Antonio Basso, who first is mentioned as a day laborer in 1874. In 1877 he was arrested by city police for building a fruit stand on the corner of Superior and Public Square. He had purchased a permit to build the stand from the city and was legally pursuing an occupation which the City Council found to be a nuisance. Basso was acquitted by a jury in September of 1877 but was shortly arrested again for the same charge. His stand and produce were destroyed by the police with damages amounting to $1000. The case against him was again dropped in November of 1877.

By 1880 he had opened another fruit stand at 45 Oregon Avenue in Big Italy, a business which he subsequently moved four times until 1900, when he invested in a saloon on St. Clair Avenue which he operated with his son until his death in April of 1907.[4] In a city which initially offered only injustice and hostility he persevered, did not become discouraged, and ultimately triumphed. He died at the age of sixty-seven, a solid citizen of the community.

The pattern followed by Antonio Basso was typical of many Italians in Cleveland. They came to this city, worked as common laborers for a few years, opened up a saloon — then considered more of a social hall than a place to drink — and became propertied citizens. They gravitated toward several different types of work, a normal procedure for ethnic groups.

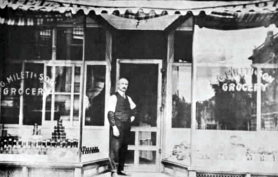

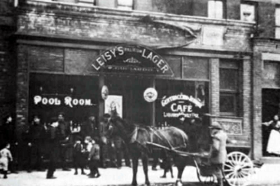

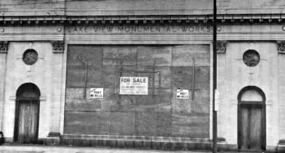

In Cleveland the Italians were late-comers, so their occupations had to be innovative or they had to evidence extraordinary skill. Thus James Broggini in 1870 and Joseph Carabelli in 1880 specialized in the creation of stone and marble monuments along Euclid and Woodland Avenues. Eugene Grasselli, an innovator in the chemical industry, became internationally known in the 1850’s and later the Grasselli Chemical Works merged with DuPont Industries. Many opened grocery stores such as G.V. Vittorio on Woodland Avenue, the brothers Schiappacasse, Casper and Salvador Corso on Broadway, and the Rini brothers, also on Broadway Avenue. Many bought saloons. In 1890, while there were only 864 Italians in the city, twelve owned saloons. By 1919 there were 18 saloons along Mayfield Road alone![5]

The main business effort of these early settlers was concentrated in the produce markets along Broadway and Woodland Avenues. By 1890 there were eight fruit and vegetable sellers in the city, four of whom were Italian including the Catalano brothers. By 1900 thirteen of the 25 produce sellers were Italians, again including the now familiar names of Frank and Michael Catalano and the Rini Brothers (Cleveland Leader, November 23, 1876). In 1900 some 26 saloons and restaurants were owned by Italians with names such as Cipra, DiFranco, Schiappacase, Mangino, Trivisonno and Zecarelle. These men and their families were to establish the economic base for a thriving Cleveland Italian community and provide leadership and direction and employment for the thousands who would follow them to Cleveland in the next 25 years.

The “Chain of Migration”

Why did they come to Cleveland, hundreds of miles from the traditional disembarkation port of New York City? Their motives to migrate to this city were basically the same as those which prompted others to leave Italy. But the single overriding factor, that of local ties, brought many to Cleveland. It has been estimated that three-quarters of all Italians migrating to Cleveland proceeded along a well-traveled course which included specific areas of the city. The single factor which seems so very important in trans-Atlantic migration to Cleveland was that many Italians were from the same village and district, links in a chain of migration stretching from southern Italy and Sicily to Cleveland.

Josef Barton’s study of Italian, Slovak and Rumanian immigration to Cleveland indicates that about half of all Italians migrating to this city moved from only 10 villages in southern Italy.[6] The major Italian districts and cities indicated are Patti and Palermo in Sicily, Benevento in the Campania and Campobasso in the Abruzzi. These regions provided about 70% of the Italians coming to Cleveland.

Many of them left their homes as individual travelers or members of a kin group, came down from the mountains and waited to board the trains to Palermo or Sant’Agata. There they remained, learning a smattering of English, or sought assistance from the St. Raphael Society for the Protection of Sicilian Emigrants. From Palermo they boarded ships filled with Slovenes or Galician Poles who had entered at Trieste. From there they proceeded to the New World and in many cases, to old friends and anxious relatives waiting in Cleveland.

Not all came directly to Cleveland from their village. Vincent Campanella, for example, was born in the Abruzzi in 1870. In 1890 he arrived in America and began work on the Pennsylvania Railroad for a few years. He then dug sewers in Cleveland and did other manual labor until he established enough capital to begin a bank in Little Italy in 1905.[7] Joseph Carabelli labored for ten years in New York City as a marble sculptor before establishing himself in Cleveland in 1880. Eugene Grasselli worked in a chemical company in Philadelphia in 1836, then moved to Cincinnati in 1839 and finally to Cleveland in 1861.

The Hometown Societies

When the Italian did arrive as part of a “migrant chain” the chances of his remaining in the city were increased. More important, his association with and participation in the several hometown societies formed in Cleveland to assist the immigrant gave the needed stability to the newly arrived migrant. Unlike the east European immigrant who organized national Slovak or Polish Unions, the Italian organizations emphasized the village and the family rather than the nation. These societies buried their dead paesani, eared for their widows, sought employment for their members, and generally provided a refuge against a foreign and sometimes hostile environment.

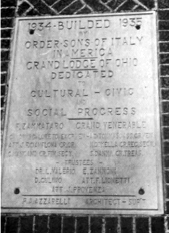

Ultimately many of these local groups sought affiliation with the national Sons of Italy organization. In 1913 Cleveland had its first chapter, and by 1920 nine lodges were affiliated with the National Sons of Italy. As Charles Feroni pointed out, one of the major attractions of the Sons of Italy was the insurance benefits and mutual aid offered. As much as $400 insurance and funeral expenses were covered by the Sons of Italy, a great inducement for membership.[8] Between the national and local societies about 80% of the Italian males in Cleveland were enrolled during the twenties and thirties.

Some of these early fraternal societies should be mentioned, for they reflect the closely knit society of Italians transplanted to Cleveland. In 1888 Joseph Carabelli, the early Italian leader in Cleveland, founded the Italian Fraternal Society. Originally part of a women’s group at Alta House, it gradually developed into the Society. In 1896 the Sicilian Fraternal Society was formed by Gaetano Caito, Cosimo Catalano and others as an organization for small merchants, bankers and lawyers. By 1900 other hometown, fraternal and cultural organizations were forming with such names as Fraterna Sant’Agata, Operaia, La Calabrese, San Nicolo Society, the Sons of Labor, and Cristofore Colombo. In 1909 Silvestro Tamburella formed the Dante Alighieri Cultural Circle in Cleveland. This effort was an early attempt to diffuse the Italian language and culture through libraries, reading rooms, lectures and similar cultural endeavors. Between 1900 and 1912 there were over 50 societies in Cleveland, three-quarters of every mutual benefit society maintained solely for persons born in a particular region or village.

One of the largest hometown societies in Cleveland was formed in 1937 by Vincent D’Alessandro and others. Since many paesani had immigrated from Ripalimosani in Campobasso it was appropriate that the Ripalimosani Social Union be formed. Known as The Ripa Cluba, it was an extremely popular and positive force in Cleveland’s Italian community. One of its major objectives was the integration of the paesani into the mainstream of American life with emphasis on citizenship. Each member was scrutinized to determine his moral and civic character. Concern for the law was essential, and any member convicted of a felony was immediately dropped from the Union. The Ripa Hall, located at 2175 Cornell Avenue, was built by the membership and is now used as a meeting place and a hall for weddings and other social gatherings.

The impact of these hometown societies upon the Italian immigrant can not be overstated. They provided the social and cultural link with the “old country” and were a strong factor in the acculturation of the paesani into the society of twentieth century Cleveland. In 1974 there were still listed some 60 social and fraternal societies in greater Cleveland.[9] They are the connection with the Italian tradition as well as the source of an intense pride in an American culture.

The Immigrant Bureau in Cleveland

Between 1880 and 1924 some 4,481,416 Italians entered the United States through the traditional ports of immigration at Castle Garden and later at Ellis Island in New York harbor. From there they were packed aboard trains to their final destinations in America. Pinned to their lapels, blouses and shirts were cards announcing their names, destinations and the familiar “W.O.P.”, an abbreviation for “Without Papers.” It has since taken a more derogatory meaning, but at the turn of the century it indicated only the hurried circumstances of immigrating.

During these 44 years more than 25,000 Italians entered Cleveland, usually by train. Beginning in 1874 a special Immigration Officer was assigned to the train stations to record those disembarking in the city and to furnish a numerical breakdown regarding their nativity. This information, generally part of the Police Report for the City of Cleveland, was officially filed with the Annual Reports of the city.

To deal effectively with the increasing numbers of immigrants the Department of Public Safety established a special Bureau of Immigration in 1913.[10] It was the first attempt by the city to recognize the many problems facing the immigrant. R.E. Cole, the city’s immigration officer during this early period, called attention to the haphazard treatment and care of the immigrant.

In his first Annual Report he emphasized the need for a more competent system of immigrant aide. “It was found that aside from the work of the Traveler’s Aid section at the depots, the arriving immigrants were at the mercy of any who would misuse and misdirect them . . . and such persons were found to be many.”[11] Especially ruthless were the cabmen and chauffeurs, who extorted large sums for short distances. In 1913 one group of three Italians was welcomed to the city with a charge of $28.00 for a fare to the Collinwood section!

The Immigration Bureau was established to assist with the many problems confronting the foreign traveler, such as arrival, relocation, settlement, and employment. The operation was systematic and seemingly efficient. The immigrant arrived in usually three types of trains; regular coaches, special “immigrant coaches” which were discontinued and antiquated cars revived for short runs from Buffalo, and “special trains” which had uncertain schedules. Many Italians arrived on these latter coaches because of the economy of the trip. In 1914 over half of the 305 trains carrying foreigners arrived in Cleveland at night and with no set schedule. Members of the Immigrant Bureau were there to meet all trains and upon arrival directed the passengers to large signs posted in the waiting rooms marked WOODLAND or BROADWAY. For those immigrants who were met, care was taken to establish that their “friends” or “relatives” were actually who they said they were. It seems that special care was taken to protect young women traveling alone, for kidnapping at the depots was not uncommon.

If the immigrant was not met, he or she was tagged with the following card:[12]

CITY IMMIGRATION OFFICE

This person is going to the address below. Will citizens, conductors and policemen please give any guidance or other help needed? Report any difficulties to R.E. Cole, Immigration Officer, City Hall, Telephone Maine 4600.

Address __________________________

Remarks __________________________

To discourage cabmen from overcharging the immigrant a “Cabman’s Receipt” was issued. On it was stated the destination and charges before the chauffeur left. Payment was made to the cabman in advance by the immigrant officer, who in turn was paid by the immigrant.

Also distributed before departure from the depot was an “Immigrant’s Guide” which assisted in “Clevelandizing” the new arrival. Printed in nine languages it contained concise information on subjects of immediate, practical value such as health care, laws, monetary values, responsibilities and opportunities for American citizenship. In cooperation with the Cleveland Board of Education a list of English language classes and citizenship classes was provided. Between 1913 and 1914, over 10,000 immigrants were enrolled in these classes.

In addition to the “immigrant’s Guide” two other manuals were prepared — a “Citizen’s Manual for Cleveland” and “Everyday English for Every Coming American.” These pamphlets attempted to instruct the foreigner on what procedures to follow in obtaining help from the official city government and how to avoid the pitfalls of trusting their own people, especially in money matters. One incident reported involved an Italian interpreter who was charging $20 to his countrymen for citizenship papers by “manufacturing” witnesses to attest that the immigrant had been in the country for the required time period. The Italian immigrant in question complained to the Immigration Bureau, where the problem was solved.

It was also reported in the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1900 that it was a common practice in Republican-controlled Cleveland to grant foreigners citizenship for a small fee during the last week or so prior to the elections. As many as 400 aliens were granted citizenship in a single day, it was reported.[13] City councilmen were alleged to carry stacks of blank naturalization affidavits which required only the signature of an immigrant, and the payment of a small charge!

In 1915 there was a decline in immigration to Cleveland which gave the Immigration Bureau the opportunity to deal with the 200,000 resident foreigners, 50,000 of whom were not citizens. John Prucha, then chief of the Bureau, recommended an increased involvement within the ethnic communities, immigrant officers who represented each of the major nationalities, and women to work with immigrant wives. His genuine concern for the foreigners’ well being and his favorable impression of these people is recalled in his message to the mayor in 1915:[14]

A large majority of the immigrants are simple people coming from their farming communities in Europe into the very vortex of our modern industrial life in a large city. Their simple life in their native village and their poverty were their protection against fraud and swindle. They bring to the United States their youth, a strong and healthy body and a willingness to work. Their customs may seem strange, their ideal crude, but under the rough surface is a determination to make good. As they enter this new life without knowing the language and the customs, without a knowledge of the law, they are exposed to various forms of graft.

He might have added that the frequent encounters with the law on minor charges such as petty theft, intoxication and disorderly conduct inflated the city’s arrest record for the foreign-born and gave the distinct impression of the immigrant as a criminal, at least in terms of total arrests.

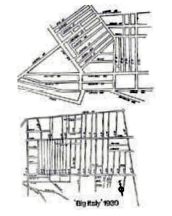

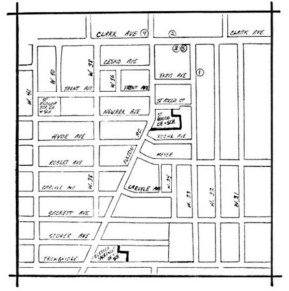

Big Italy and Hiram House

Once the Italian immigrant had arrived in Cleveland two problems were given immediate consideration, where to live and how to earn a living. The concept of the ethnic neighborhood seemed to solve both concerns, for each ethnic settlement in Cleveland provided in varying degrees the security needed for adjustment and survival in the city. The first Italian community was commonly known as Big Italy and was located along Woodland Avenue from Ontario and Orange Avenues to East 40th Street. At the turn of the century this section was populated by about 93% Sicilians and was the center of the city’s produce markets.

It was in this locality that Frank Catalano and G.V. Vittorio began their enterprises, Catalano at 839 Woodland and Vittorio at 746 Woodland.

Originally the community was located in the downtown section which was then known as the “Haymarket” section but later moved eastward along Woodland Avenue from East 22nd to East 40th Street. Today Galucci’s and Bonafini’s Italian importing houses are the solitary remnants of this original Italian settlement. St. Maron’s Church at 1245 Carnegie Avenue now serves Cleveland’s Lebanese Americans but in 1904 was known as St. Anthony of Padua Church, the first Italian Catholic Church in Cleveland. It was the religious landmark of Cleveland’s original Italian settlement.

Of the section known as “Big Italy” little is known except for scattered information surviving from the Hiram House Settlement. Originally this area along Woodland and Orange Avenues had the center of Cleveland’s Jewish population. Hiram House, located at 2723 Orange Avenue, was an attempt to assist the immigrant with various social services, language classes, vocational training and recreational activities. In the early 1900’s the area surrounding Hiram House was one of moral and social decay. A 1909 Visitor’s Report from Hiram House indicated that “saloons are frequent here, some being the lounging places of the lowest type of men and women.”[15] Characters such as “Frog Island Kate,” “Babe Downs,” and “Old Mother Witch” gave the neighborhood an unsavory reputation.

As the Italians began to move into this neighborhood they were exposed to the crime, vice and social disease which was already part of the settlement. There were the “Zookeys,” a juvenile gang of Jews and Slovaks led by a black youth whose delinquency was soon overshadowed by Joe Amato and his “Robber Gang.” It seems that this brand of ethnic criminality was innocuous by today’s standards. They were involved in knife fights, but mostly thrived on invading and disrupting the Hiram House playground, stealing fruit and penny candy, and throwing rocks at the streetcars.

The transitional period between 1908 and 1916 was marked by fierce rivalry between the Jewish immigrants and the Italians in this area. Throughout this period fights between Jews and Italians were frequent at the Hiram House settlement. One report in February of 1915 described a basketball game between a Jewish and an Italian gang:[16]

The gymnasium was the only department which really drew the Italians. The Jewish boys began to object to so many “WOPS” coming in. For the first time in the history of the gym the Jewish boys found Italians who would not be shrinking and sensitive . . . and who would not be driven out . . .

A fight erupted and concluded with the Italians pulling knives and chasing the rivals out of the gym.

Hiram House was begun by George Bellamy, an ultra-conservative social worker whose social philosophy ran the gamut from philanthropy to racism. Many of his associates reflected his cultural predisposition and were in fact greatly chagrined when the Jewish population began to give way to more recent southern and east European immigration. Miss Mitchell, one of the supervisors at the settlement, commented on this transformation by observing that “In place of the Jews with their splendid morals and intense home life, we have the fiery Italians, and the Slavish and Polish with their duller minds, their drunkeness and immorality.”[17] As the Italians kept moving into the settlement region the conflict of cultures would become inevitable.

But the Italians had come to stay in this Woodland Avenue community and were replacing the other ethnic groups. By 1916 a heavy Italian population was concentrated between East 22nd and East 29th Streets. About a third of the 359 Italians listed in the Hiram House records were laborers with another 64 listed as operating retail outlets.[18] Many of these residents were attracted to Hiram House for the varied cultural and vocational experiences offered by the settlement. They felt that if programs dealing with music were started more Italians would become attracted to the settlement, so Dominic Villoni and Frank Russo were permitted to organize two bands which were enthusiastically supported by the neighborhood. Later, operatic selections, especially recordings by Caruso, were purchased for the settlement.

By advertising in La Voce the Hiram House settlement brought in Italians for the manual training programs, especially printing. The women were attracted to the sewing and cooking classes and were obviously good at it. A 1911 report stated that the Italian girls were splendid seamstresses — at all ages — and took an obvious pride in their work.

If Hiram House marginally accepted the Italian immigrant at first, there was still a basic lack of commitment toward these immigrants. At a time when the settlement was predominantly Italian no full-time staff worker spoke Italian; only six part-time volunteers were proficient in the language. Even after the Jews had left the area and had relocated along East 55th they still dominated the officials at the settlement. Basically Italians participated in a social settlement house which made little attempt to understand or supply their particular needs.

The final chapter of the Italian community along Woodland Avenue really centers around one man who helped breach the chasm between Anglo conservatism and Italian simpaticatezza. He was Francesco Gasbarre, himself an Italian-born immigrant, who was known as Frank Casper. His employment at Hiram House in the twenties was marked by a real understanding of and involvement with the Italian community. During his years as a full-time staff member he marched in the Italian festival parades, participated in their hometown meetings, even organized an Italian Mothers Club.

Casper appreciated Italian culture and cultivated its survival at the social settlement. He produced several Italian musicals in English for the general settlement. Whenever Italian opera singers were in Cleveland, Casper made it a point to have them at least visit the settlement. His cultural masterpiece was the annual “Spring Festival,” which was begun in 1924.[19] Every ethnic group at the settlement participated, and in 1925, Italian, Russian, Mexican, Slovak and Bulgarian performers contributed to the show.

The same approach was followed with regard to drinking. Red wine was especially popular among the Italian people, most especially at weddings. Prohibition notwithstanding, it was the custom that at festive occasions wine would be served. Nothing of the sort was to occur at Hiram House. Whenever Casper was involved with a wedding reception at the settlement, he overlooked this dictum whenever he could. Abuses of this “illegality” were hardly ever flagrant but made a lasting impression upon the Italians who saw Casper as a man who understood the difference between wine as a food and alcohol as an escape. Unfortunately prohibition officers did not have the same perspective on life nor understanding of Italian culture.

By the mid-1920’s many of the Italian hometown societies moved their meeting places out of Hiram House and into the East 116th Street settlement. This was to be only the beginning of a mass exodus of the inhabitants of Big Italy away from the downtown location and toward the eastern regions. The reason for this change can be explained by the fact that the neighborhood was declining and that there was more space and better housing in the Collinwood, Murray Hill and Kinsman Italian communities.

Just as the Jews saw the Italians as a threat to their neighborhood supremacy, so too the Italians felt the influx of blacks into “Big Italy” to be an encroachment. In the decade ending in 1930 the Italian population recorded in the census tracts as living in “Big Italy” fell from 4074 Italian-born in 1920 to 2063 in 1930. More Italians were coming into Cleveland but they no longer lived in the original settlement. By 1940 only about 1300 Italians remained in “Big Italy.”[20]

Italians participated in the Hiram House community and continued to inhabit “Big Italy” as long as it was predominantly Italian. They ceased to participate in Hiram House programs when they no longer counted in its leadership. Being a tightly knit group and relatively mobile, the Italians chose to remain aloof from activities which no longer catered to their ethnic traditions. Moreover, as the other Italian communities grew they drew Italian involvement away from the multi-ethnic and multi-racial environment of the Hiram House settlement and into their own communities.

Ironically as the officials of the settlement house began to sense that the Italians were not such a bad lot after all, they tried to keep the Italian interest in their activities alive by opening branches of the Hiram House in the new Italian neighborhoods. In 1924 an attempt to create a branch in the East 116th settlement failed. In 1926 another extension was begun at the Anthony Wayne School at East Boulevard and Woodland Avenues, but by 1929 only 20% of the adult classes were attended by Italians. Too little attention had been paid to these immigrants from the beginning and when the very existence of Hiram House was at stake the leaders sought out the very group they had ignored for involvement in their community activities. This ack of “grass roots” participation and the deterioration of the neighborhood around Hiram House led to its closing in 1941.

Hiram House was a reflection of a temperate and relatively conservative approach toward social organizations. Gambling of any kind was prohibited on the settlement grounds, thereby limiting hometown festivals which included raffles and other games of chance. Italian parades did begin and end at the settlement but any other socializing had to be done elsewhere.

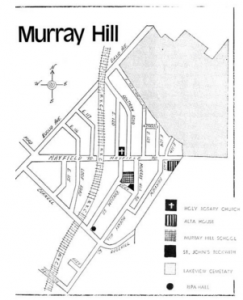

Little Italy

Another major Italian settlement in Cleveland was “Little Italy” located from East 119th to East 125th Streets on Murray Hill and Mayfield Roads. In 1911 it was estimated that 96% of the population of this neighborhood was Italian-born and another 2% were of Italian parents.[21] Many of these Italians were Neapolitan and were engaged in skilled lacework, the embroidery trades and garment making. The largest district group came from the towns of Ripamolisano, Madrice and San Giovanni in Galdo, which are in the province of Campobasso, in the region known as the Abruzzi.

It was in this neighborhood that the skilled stonemason Joseph Carabelli founded his marble works. He was a unique man in a number of respects. He was northern Italian and a Protestant, which placed him in a distinct class in relation to the “typical” Italian immigrant. He was a native of Porto Ceresio and immigrated to America in 1870 at the age of 20. He spent ten years in New York City as a sculptor and carved the statues for that city’s Federal Building.[22] Settling in Cleveland in 1880 he began the Lakeview Marble Works, became a close friend of John D. Rockefeller, was elected to the Ohio House of Representatives and became a major figure in the affairs of the Italian community of Cleveland.

It was also in Little Italy that Vincent Campanella opened his banking business. Born in the Abruzzi, he immigrated in 1890. During his early years in this country he worked in the coal mines of Pennsylvania, in the construction of railroads, dug sewers in Cleveland, and ultimately created a surplus of capital to invest in a bank. His career in banking was very successful but he never changed his general philosophy that life should be accepted as it unfolds, for better or for worse. He is credited with remarking that “America has treated me well . . . she has paid me 10¢ a day . . . and she has paid me $5000 a day.”[23] For most other Italians in Cleveland wages usually amounted to $1.00 per day and the people were grateful to receive this wage.

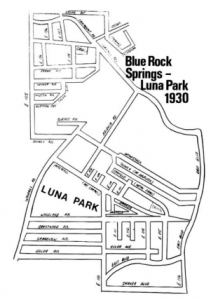

From these two major settlements sprang other colonies which would absorb later Italian immigration to Cleveland. While Murray Hill was developing during the early 1900’s two other settlements were forming. On the east side near East 105th, Cedar and Fairhill Roads the third Italian community was established. These settlers were primarily from Campobasso and specifically from the town of Rionero Sannitico. Simultaneous to this settlement a community was forming on the west side in the vicinity of Clark Avenue and Fulton Roads. Many of these immigrants were from Bari, on Italy’s southeast coast, and Sicily.[24]

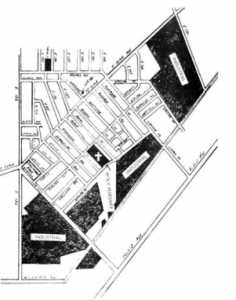

Just prior to World War I a fifth Italian colony, in Collinwood, was formed. In an area bounded by Ivanhoe Road on the west, St. Clair Avenue on the north and the New York Central tracks on the south, Italian families poured into this community. In 1910 Collinwood was formally annexed to the City of Cleveland and brought another Italian settlement within the city limits.

The Italian Churches in Cleveland: Roman Catholic and Protestant

In each of these communities certain landmarks served the community as social, religious and cultural centers. Usually these were the Italian churches which were so important in each area’s development. Although in Italy local parishes received small support from the parishioners, in America the ethnic church became the center of the community’s life. Even if these religious institutions were not always supported financially by their Italian members their importance can not be overstated.

The original Italian settlement founded St. Anthony of Padua Church in 1887. It was first located in a blacksmith’s shop opposite the East 9th Street cemetery. In 1904 it was moved to a new building at 1245 Carnegie. According to one source, during World War I St. Anthony’s Parish embraced more than 10,000 people from the Scovill, Central and Woodland districts. However, as the Italians abandoned this locale they also ceased to attend St. Anthony’s. In 1938 the church was sold to St. Maron’s, and St. Anthony’s Parish merged with St. Bridget’s on East 22nd and Scovill.[25] In 1956 this parish was moved to 6750 State Road in Parma.

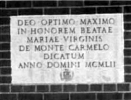

In the Mayfield Road-Murray Hill district Holy Rosary Parish was founded by the Scalabrini priests in 1892. By 1908 it had reached an enrollment of 940 families. Father Joseph Strumia was the first pastor of the church and was succeeded by Father Givelli in 1894. On January 25, 1905, ground was broken for a new church and in 1908 a new edifice was dedicated at the corner of Mayfield and Coltman Roads. Part of the lands on which the church was built was deeded to the bishop of Cleveland by Joseph Carabelli and his wife for one dollar. There was a one thousand-dollar balance on the property which was assumed and promptly paid by the diocese. In December of 1973 Holy Rosary had approximately 1000 families, an increase of only 60 families since 1907.

For Holy Rosary Parish the major event in the life of the church and the community is the celebration of the Feast of the Assumption held on August 15th each year. Beginning with a mid-morning mass a procession bearing a statue of Mary, Mother of Christ, is carried out of the church and placed on a carriage. For two hours the Madonna makes its way through the streets proceeded by a band, uniformed Knights of Columbus and school children dressed in their First Communion outfits. In the evening the streets are blocked off and a carnival is held in the business district along Mayfield Road. As many as 40,000 people attend this feast each year, reliving the religious pageantry of the old country with new world paesani.

St. Rocco’s Parish on Fulton Road developed early in the century and established its own St. Rocco’s day celebration in 1915.

In 1922 the church was founded and was guided by Father Sante Gattusso who served this community until his death in 1956. When he arrived at St. Rocco’s the collection was bringing into the parish only $10 per week. Within two years he had raised $1400, bought property and built a small church. During the Depression, men from the parish used old railroad ties and trees to heat the school and the church, and discarded bricks taken from demolished buildings were used to build an addition to the school.

In 1950 it was decided that a new church was needed and one of the most unique stories in Cleveland’s Italian past began. The men of the parish had been collecting bricks, stones and slabs of marble from construction sites and had stored them on the church grounds until it began to resemble a junkyard. Using ropes and muscle, the men began to build a church, hoisting the stones forty feet above the ground and fitting them into place.

During the evening eight men would work and on Saturdays this figure doubled. After two and one-half years of work the junkyard of materials had been assembled into a beautiful stone church seating 750 members. The church was dedicated on March 16, 1952, by Archbishop Edward F. Hoban. The efforts of these men had saved the parish some $250,000 and had renewed a sense of pride within the entire community.

Today St. Rocco’s still retains its large Italian population, many of whom are Italian-born. The 1970 census reported that 597 persons living in the area were born in Italy, about one-third of the entire population of the area. Hometown societies, the Trentina and the Noicattarese along with the North Italian Club still flourish in the area.

Another Italian nationality church, St. Marion, did not survive the post-World War II period. Founded in 1905 in the Blue Rock Springs area by immigrants from Rionero Sannitico, St. Marion became the center of Cleveland’s third Italian colony. Although St. Marion remained a small parish the residents of this settlement built the first Italian parochial school in the city. In 1924 the school opened its doors to forty Italian youngsters. Eventually it enrolled some 200 children. By 1936 St. Marion’s Parish accounted for 500 families who had managed to keep the school open during the depression years.

During the post war period the Italian residents’ desire for better housing combined with Western Reserve University’s expansion programs to accelerate migration to other areas of the city. By 1953 St. Marion’s population had dropped to 100 families and the school closed in 1966. In 1968 only 15 Italian families remained in the area. In 1967 when Father Francis Valentini came to St. Marion’s he found an empty convent, an empty school and a church with little parochial life remaining. St. Marion’s Catholic Church held its final mass in 1975. The structure is now the Second Bethlehem Baptist Church.

Another nationality church is Holy Redeemer, located on Kipling Avenue in the Collinwood district. Founded in 1924 by Father Marin Campagno, it remained a frame structure until 1927.

In 1964 a new Holy Redeemer was dedicated. In this Italian settlement some 1400 families are registered in the parish, with over 85% being of Italian extraction. Since many of these members originally came from the Murray Hill section they brought with them many of the traditions of “Little Italy,” such as the feast of the Assumption and the ensuing festival.

Although the majority of Cleveland’s Italians are Roman Catholic, several Protestant churches have attracted numbers of Italians to their congregations. St. John’s Beckwith Church in “Little Italy” was an early example of Protestant missionary activity in the Italian community. Founded in 1907, St. John’s was one of four mission churches established by the Presbyterian Church. It was begun through a grant from the T. Sterling Beckwith Fund and attracted some Italian families living along Mayfield Road.[26]

The first pastor of St. John’s was the Reverend Pietro Monnet, who established the church in 1907 at the corner of Murray Hill and Paul Avenues. Joseph Carabelli donated the baptismal font and the Euclid Methodist Church gave the pews. In 1921 St. John’s was united with the Euclid Presbyterian Church as part of the Church of the Covenant.

Perhaps the church’s most famous pastor was Reverend Gennaro D’Anchise, from Campobasso, who had been the director of the Bureau of Immigrants for the American Waldensian Society. Returning to Italy in 1920 he was “removed” by the fascist government and returned to Cleveland in 1929 when he began his ministry at St. John’s. By 1941 his parish membership had a following of some 106 families and in 1948 about 200 families filled the congregation.

The average yearly contribution in 1948 was only $10.50, and this factor had a significant effect upon the demise of the church.

Most of the members lived within one mile of the church but attendance was never more than 40%. Despite D’Anchise’s encouragement and efforts to promote Italian culture little effective progress was made. Hampered by the rather hostile attitude of the local Italian Catholic population, the church declined rapidly after 1950. It was finally closed in 1962 and is now occasionally used as a community hall in “Little Italy.”

Another Protestant church in Cleveland was St. John’s Italian Baptist Church, founded in 1930 on Soika Avenue and East 123rd Street in the Kinsman Italian community. Reverend Vito Cordò, its first pastor, held services in English and Italian, but his efforts proved fruitless. He retired in 1956 and St. John’s Baptist continued for two more years before it also was sold to a Black Baptist congregation.

In the original Italian settlement around Hiram House the Josephine Mission of the Euclid Avenue Baptist Church attracted some Italian converts during World War I. Many of these were drawn to the mission because of the classes offered there, especially those in sewing. Another Baptist congregation was founded on East 33rd Street between Woodland and Scovill Avenues in 1909. It also became extinct by 1919 when only 37 parishioners still attended services. In the Collinwood settlement the Church of the Savior was established on Kipling Avenue as an extension of St. John’s Beckwith. Begun in 1916 by Reverend Monnet, it was attended by former residents of Little Italy. Like the other Italian Protestant churches they found that they could not compete successfully in a predominantly Roman Catholic area. By 1919 the Church of the Savior counted only 57 members in its congregation.

Ethnic Mobility among Italians in Cleveland

As Big Italy declined in population in the late thirties other settlements experienced a perceptible increase in population. This would tend to substantiate the belief of some that an ethnic neighborhood is a strong factor in the retention of an ethnic identity. Little Italy, part of census tract R-8, was already evidencing a reduction of Italian population in the decade prior to World War II. In the 1920 census some 3460 Italians were counted, while the 1930 census showed only 1226 Italians. But the areas adjacent to Little Italy rapidly increased in population. The Woodhill-East Boulevard Italian section increased from 653 Italians in 1920 to 1233 in 1930. There was that marked tendency to remain together as a group despite changes in location.

To the south the settlement encompassing Kinsman Road on the north and the Erie railroad on the south witnessed a dramatic increase in Italian settlers. Beginning with a population of 528 Italians in 1920, it climbed dramatically to 2666 by 1930.[27] To the east the Collinwood settlement from East 152nd and St. Clair to East 171st, also became a receptacle for Italians leaving Big Italy. The 1920 census reported only 1269 Italians in the neighborhood, but over 2100 in 1930. In fact, the Collinwood census tract indicated that Italians made up almost 69% of the total population of the area and 78% of all of the foreign-born in the community.

The shift in Italian population was primarily to the eastern regions and not to the west side. The area around St. Rocco’s experienced an increase of only 111 Italians in the decade 1920-1930. The census figures show only 759 Italians living in the area in 1930. From West 65th to West 85th, the Mt. Carmel community, an equally low growth rate was recorded. In 1920 only 685 Italians were listed in the census. In 1930 it had increased to only 702. This figure represented only 15% of the total population of that census tract so that this Italian enclave was but a small group within a heterogeneous population mixture.

If we go beyond the bare population statistics for 1930 in each of these communities some rather interesting observations can be made about the Italians living in the major settlements in Cleveland. For example, in 1930 the average Clevelander who owned a home had a dwelling which was worth $6971.

In every neighborhood with a sizable Italian population the average fell into the range $5000-$7500. This is not to imply that every Italian owned a home, but that in general the Italian neighborhoods were at least at the city average in their living accommodations. Indeed in the Collinwood settlement 41% of the population owned their homes while along the Woodland Avenue community another 41% were home owners.

On the west side, St. Rocco’s area listed 50% of the population owning dwellings. This would tend to substantiate Josef Barton’s study which indicated that only about 14% of the Italians in his survey remained propertyless after twenty years’ residence in Cleveland. To the Italian who could afford it and to those many who could not the investment in property was the best method of maintaining a stable environment and was the course most Italians chose.

Yet another statistic probably is more indicative of Italian housing patterns in 1930 — rental property values. In that year the average rental price in the city of Cleveland was $36.25 per month. No Italian settlement reached that figure although the Collinwood and Kinsman settlements were averaging $35 per month. The Murray Hill community had one of the lowest rates in the city with only $28 per month. One can only surmise what these dwellings were like but they did exist amidst middle class residential property.

There has been a recurrent charge made about the mobility of the Italian immigrant, returning home every two or three years to Italy, never really perceiving America as a permanent home. Prior to the 1924 immigration restrictions this may have been the case. After that date, however, the concept of permanence seems to have taken hold. This is indicated in a number of ways. One is by the number of naturalized citizens as well as by those who had made the initial effort to obtain first papers. The following chart illustrates this phenomenon by using the statistics, provided by the 1930 Federal Census, of those applying for citizenship:[28]

| Area | Total Foreign Born | Total Naturalized | First Papers | Aliens | Number of Foreign-born Italians |

| Murray Hill (R-8) | 2380 | 1165 | 169 | 819 | 2227 |

| Collinwood (Q-5) | 2433 | 1158 | 341 | 892 | 2106 |

| St. Rocco’s (B-9) | 1431 | 748 | 148 | 513 | 759 |

| Kinsman Rd. (T-5 to T-9) | 12,788 | 7144 | 1392 | 4005 | 2366 |

Italians in the Professions during the EarlyYears

Cleveland’s early Italian communities produced many prominent individuals in a variety of professions. Mention has already been made of Joseph Carabelli whose granite and marble works attracted others from Italy to settle in Cleveland. A friend of John D. Rockefeller, he influenced that oil magnate to fund Alta House on Mayfield Road for the Italian neighborhood. In 1908 he was elected to the State House of Representatives on a Republican ticket. He was instrumental in having October 12 designated as Columbus Day in Ohio. He died in 1912, the first Italian elected to a major office in the state.

Vincenzo Nicola left Monterero Val Cocchiara in Campobasso in 1881 for Ulrichsville, Ohio. His son Benjamin went to Ohio State University, passed his bar examination and in 1904 became the first practicing attorney of Italian extraction in the city of Cleveland. Nicola practiced law in Cleveland until 1964. During his career spanning half a century he was appointed U.S. Commissioner in 1930 and a judge of the Common Pleas Court in 1948. He also served on the Board of Directors of Alta House as well as the Urban League.

By 1919 at least 12 Italians were listed as attorneys in the city, most of whom advertised in the weekly La Voce under the heading “Avocati.” Among these were Joseph Nuccio, who would later become assistant city prosecutor. B.A. Bvonpane, an articulate spokesman for the Italian community, was also among this group, along with Louis Perry, D.J. Lombardo, Michael Picciano and Louis Lanza.

Another lawyer of prominence was Alexander De Maioribus, who was to become the first Italian-American to be elected to Cleveland’s City Council in 1927. A member of the Republican party, he served in Council from Ward 19 until 1947 and was president of that body for eight years, from 1936 to 1944.

During this formative period a number of distinguished Italian-American physicians and dentists were found in the city. Dr. G.A. Barricelli of Murray Hill was a specialist in pulmonary and cardiac work and was an occasional lecturer at Western Reserve University. He was also an outspoken supporter of the Italian-Americans in Cleveland and was a frequent contributor to the editorial pages of La Voce as well as the English-speaking dailies. His wife, Dr. Orfea Barricelli, also held a position in the literature and language departments at Western Reserve and was a president of Il Cenacolo, the Italian Cultural Organization.

It has been observed that the Italian professional men in Cleveland lived by the needs of the peasants. Indeed a good case could be made for this assertion, for during these developing years those Italian-American doctors, dentists, lawyers and businessmen who had their offices in the several Italian settlements catered to the wants and needs of their own people. For the Italian doctor or lawyer, his ability to communicate in the language of his constituents was a most important attribute. It was certainly a good business practice.

The banking establishments along Woodland, the Gugliotta Brothers, Nicola and Salvatore, and Vincent Campanella in Little Italy, did business with usually an Italian-based clientele. Joseph Russo and Son’s Ohio Macaroni Company was begun in 1910, while Albert Pucciani’s Roma Cigar Company began three years later. G.V. Vittorio’s store on Woodland Avenue specialized in olive oil, anchovies and other Mediterranean specialties hardly noticed and certainly unappreciated by native Clevelanders. But for the community in which he did business his was a mecca for these delicacies, a culinary bridge between Italy and Cleveland.

Early in this century Italians were involved in various aspects of the food industry. We can only speculate why this particular occupation has attracted so many Italians and probably never arrive at a conclusive answer. Perhaps the best explanation would be summed up by the idea of “possibilities.” The potential in the restaurant business was, at that time at any rate, limitless, and so the possibility became the attraction, the magnet which pulled an immigrant such as Guiseppe Z. Botta toward success. He arrived in Cleveland in 1902, worked as a waiter for seven years and by 1909 opened a restaurant of his own. He would then employ others from Sicily, perhaps some of his paesani from Sant’Agata, to work for him. With them and others he later organized the Sant’Agata Workers Society in 1915.

By 1920 it was reported that four of Cleveland’s finest restaurants were owned by Italians, a phenomenal accomplishment by any standards. One of them, the New Roma on Prospect Avenue, was said to be the largest in Ohio. Italian chefs managed the culinary duties at the Hotels Statler, Cleveland, Hollenden and at the Shaker Heights Club. It was estimated that during the 1920’s seventy percent of the cooks in Cleveland’s restaurants were of Italian descent.[29]

In 1910 Samuel P. Orth wrote a three-volume History of Cleveland which was more of a biographical survey of this city’s illustrious citizens than anything else.[30] In the second volume of this work are listed some 400 Clevelanders, six of whom were Italian. Joseph Carabelli is listed as are the Caito Brothers, who were fruit merchants along Broadway. Two priests are noted, the Reverend Humbert Rocchi of St. Anthony of Padua Church and the Reverend Guiseppe Militello, pastor of Holy Rosary Parish. Benjamin Nicola, the attorney, and Nicola Cerri, the Italian consul to Cleveland are also briefly mentioned.

The most impressive treatment afforded an Italian is given to Eugene Grasselli, whose name is linked to the chemical industry, to John Carroll University, to the Cleveland Public Library, to the Cleveland Museum of Art, to duPont Chemicals. Ironically Grasselli was born in Strasburg in 1810, the son of Jean Angelo Grasselli, a chemist. Thus it is obvious that Eugene Grasselli was not a first generation Italian but did have an Italian background.

Eugene Grasselli emigrated first to Philadelphia in 1836, then to Cincinnati in 1839, where he established a small chemical plant. In 1861 he arrived in Cleveland and soon organized the Grasselli Chemical Company. His plant was located on East 26th near Broadway and Independence Roads and initially manufactured sulfuric acids used in the refining of oil. By 1885 Grasselli Chemicals Incorporated had a net worth of $600,000 with plants in seven states and Canada.

Eugene Grasselli died on January 10, 1882, and his son Caesar continued the company’s operations. On the eve of World War I the Grasselli chemical works were worth some 20 million dollars and became involved in the manufacturing of explosives. Caesar’s son Thomas consolidated the company with duPont Chemicals in 1926 and was made a vice-president of that concern. In 1936 Grasselli Chemicals was incorporated as a department of duPont thus ending a century of leadership in the chemical manufacturing field.[31]

Today the name Grasselli is associated with John Carroll University, for the Grasselli Tower and the Grasselli Library on the campus. A plaque at the Cleveland Public Library indicates that Eugene Grasselli was a trustee of this nationally known institution. The Grasselli’s were also benefactors of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

For each illustrious success story such as Carabelli, Grasselli or Nicola, thousands of other Italians managed only to survive in the city. Indeed, a cursory examination of Cleveland’s City Directory from 1910 to 1920 will indicate the persistence of obscurity for most Italians entering the city. They began and ended their work careers in Cleveland as common laborers, a condition which was partially caused by their general lack of education, as well as by the undertones of discrimination in hiring. There was also the positive attitude toward manual labor which was important to many of the immigrants from the rural southern Italian towns. It was an honorable way to make a living so many continued in this occupational strata.

A few examples will illustrate this point. Michael Valentino and Angelo DiRienzo began working in Cleveland in 1908 as common laborers. Eleven years later DiRienzo is still listed as a laborer, Valentino having dropped out of the listing in the City Directory. Others such as Pietro Cannavini started out as laborers but soon discovered that Cleveland was not what they had expected and left the city. Cannavini probably was among the “birds of passage,” those immigrants who periodically returned home to Naples, Palermo, or some village in southern Italy for a more secure existence. Statistics are inconclusive on this matter, but a rough check on entries and those remaining by the next Federal Census indicates an average loss of about 39% of the Italians yearly. This percentage is generally substantiated by national figures which show that in some years Italians leaving the United States almost equaled those immigrating to America. Between 1908 and 1916, 1,499,907 Italians entered the United States while 1,215,998 returned to Italy.[32] After the 1924 Immigration Quotas were set, the number of Italians leaving was substantially decreased.

Upward mobility on a small scale is evident among the Italians in this city and the story can be told again and again of the laborer who persevered and was rewarded by an improved occupational status, however marginal it may seem to us. Pietro Trivisono, living at 168 Carabelli Avenue was listed as a laborer in 1904 and remained as such until 1916 when he had assumed the occupation of a general contractor. Antonio Caputo began as a laborer in Big Italy in 1908 but in 1920 we find him listed as a baker and living in Murray Hill. In 1925 he was living in the Collinwood settlement, still as a baker.

Barton’s study indicates that among Cleveland’s Italians there was a good deal of occupational mobility. Generally speaking, of those Italians who were studied, only 25% of the second generation Italians remained in the same occupation as their fathers. The sons of Italians who had been laborers and peasants in Italy generally ended up slightly better than their fathers. Of the 250 families studied only 14% were propertyless after living in the city for 20 years. They were more likely to invest in a house and a lot than in other material comforts and thus rapidly became part of a growing and stable middle class population within the city.

This sense of permanence can also be indicated in several ways other than property ownership. In 1902 there were over 300 registered Italian voters just from the Murray Hill section of the city. In 1909 La Voce de Popolo Italiano was urging its readers to register as citizens and to vote for certain Republican candidates. Other issues of La Voce provided typical questions and answers in English and Italian relating to governmental operations in the United States. These were the types of questions which could be expected on their examinations for citizenship.

La Voce also published a “Commercial Guide” to assist the Italian reader in spending his wages. The Cleveland business community bombarded the paper with advertisements by Italian and non-Italian concerns. Burrows, Cleveland Trust, The May Company advertised along with Carabelli and Russo. A bakery from Pittsburgh and a “Grosseria Italiana” from Columbus, Ohio also ran ads to attract Italian consumers.[33] The May Company and Cleveland Trust set up “Italian Departments” in their stores to accommodate the Italian-American shopper. The Italians were here to stay and their business was eagerly sought after.

Poor Relief and Crime

Another indicator of a group’s stability and general desire to contribute to their immediate surroundings is their reliance upon public institutions to care for normal familial responsibilities. It is obvious that for every individual group there may be a period of adjustment, of acculturation, during which public assistance is necessary. Add the impediment of learning a foreign language and the cultural differences, and it would seem logical that the foreign-born would depend on public help to a relatively large extent.

In addition the complexity of a foreign legal system where almost one hundred actions were determined to be illegal, numerous confrontations with the law would be expected. It is true that during the first quarter of this century the foreign-born did participate to a larger extent than the native-born Clevelander in relying on public welfare. But the Italian immigrant evidenced one of the lowest rates of involvement with public assistance and a reasonably low rate of arrest and detention in the city.

Using official departmental reports on Poor Relief in the city from 1874 to 1930 there is a definite indication that Italians did not request public aid to any great extent during this period. In 1910, for example, 2544 families received public welfare from the city, of which 1799 were foreign born. Italian relief constituted only .09% of the foreign born and only .06% of the total on relief. This figure representing 159 Italians was the highest rate of public welfare experienced by the Italian community until the Depression years. (See Table E in Appendix: Native and Foreign Born Clevelanders Receiving Public Assistance.)

In most cases an individual remains an obscure part of an ethnic group until he or she comes in conflict with the legal structure of a community. However distasteful or unfortunate these stereotypes may be, it is apparent that such adverse publicity has affected the image of certain ethnic groups. The stigma of criminality has been attached to the Italians even though there is empirical evidence which points to the contrary.

The Cleveland Police Department issued an Arrest Report each year indicating the total number of arrests, total foreigners arrested, with a breakdown by Nativity. Table F indicates a composite of Italians arrested in Cleveland until 1902 when the Nativity charts were no longer published. The arrest rate for Italians was relatively low when compared to the total arrested, although it was high considering the Italian population prior to 1910. Italians averaged about 4% of the foreigners arrested.

It should be kept in mind that arrests do not necessarily imply convictions and that the total arrest figures reflect all types of crimes, misdemeanors as well as felonies. Serious crimes usually involved incarceration and this figure may be used as an indicator of serious crimes charged against Italians. The following chart indicates Italians in the city’s House of Correction (based on available information):[34]

| Year | Total in House of Correction | Foreigners | Italians | % of Total |

| 1910 | 2252 | 730 | 39 | .02% |

| 1911 | 2433 | 906 | 70 | .03% |

| 1912 | 2372 | 841 | 94 | .04% |

| 1913 | 3591 | 1222 | 97 | .03% |

| 1915 | 4735 | 1659 | 93 | .02% |

| 1922 | 1400 | 610 | 96 | .068% |

| 1928 | 9836 | 2532 | 124 | .0126% |

This does not imply that Italian crime was negligible nor that it was non-existent, but it does imply that such crime did not reach epidemic levels as some would believe. Yet to read official statements on criminality in Cleveland one would get an entirely different impression.

A Report issued by the Cleveland Association for Criminal Justice stated that from October to December, 1922, 96 Italians were arrested for felonies out of a total of 923 whites, 610 foreign born, 477 “colored,” and 104 Austrians. During the year 1927 Sabastian C. was convicted of rape and murder. Sam B. was found insane after convictions for three murders and Ross M. and his non-Italian gang of “boy burglars” were convicted in the same year. The 1928 Report foretold that “Cleveland is today fertile territory for ‘organized crime’ of all kinds.” Crime was indeed on the rise in the city and the statistics tell the story. It was in the foreign and “colored” elements within the city that the real source of criminality was to be found.

The Italian community was quick to report and denounce rather than defend the criminal element within its midst. An early issue of La Voce warned the readers of a counterfeiter working within community as well as reported the murder of an Italian by another in East Cleveland. Almost every issue reported an assault, a robbery or manslaughter within the Italian sector, of Italians harassing other Italians. The April 24, 1915, edition of La Voce reported the murder of “Big Dominic” M. on Orange Avenue by two other Italians while another Italian was assaulted on Race Avenue.

These were isolated examples of crime within an ethnic community. No settlement was free of it. As the Italian-born element grew in the city and as the foreign born population reached over 230,000 in 1930, inter-ethnic strife was expected. Yet within the Italian neighborhoods one institution, the family, provided the bulwark against an epidemic of anti-social behavior.

Miss Florence Graham, the assistant principal of the Murray Hill school from 1908-1928 and principal there from 1937-1957, provided an “outsider’s” account of the Italian community during the 1920’s. While in the home parents were the only authority, the school became the real as well as the legal extension of the family. In the Italian tradition the school teachers were looked upon for leadership and were treated with respect. “I think that was why they accepted us so well. When the teacher said something was so . . . the Italian said, ‘that’s right and don’t question it.'” This deep respect for authority, the subverting of the individual’s “rights” for basic unity and order, is a main current in the history of the Italian people whether in Italy or in America.

Miss Graham also commented on the stability of the Italian home:[35]

During the first period when I was in Little Italy (1908-1928) the parents were in the laboring class. They worked like clockwork. The fathers came home at a certain time and the mothers were there preparing the meal. One knew where the mother was. That’s why they had such wonderful families . . . because they were sure of their homes.

This sense of stability and security was carried out of the home and into the streets by the children. Boys were home by 7:00 p.m. Girls were closely watched. Delinquency was practically nonexistent during this time. In 1928 at the Cleveland Boys Farm only three Italian-born youths were admitted while only 18 second-generation Italian youths were incarcerated. This was in a city which had reached nearly 900,000 people with almost 23,000 Italian-born within the population.

In conclusion, the formative period of Cleveland’s Italian settlement witnessed an increase in population, a relatively low crime rate, an almost negligible dependence on public assistance and a propensity to purchase real property within the city. Commercially, culturally and socially the Italians were accepted and encouraged by their Cleveland neighbors to continue their efforts to contribute to the city’s growth and development. Prohibition and the rise of fascism proved to be discordant factors in this otherwise harmonious relationship and altered some of that encouragement to outward signs of concern and even hostility.

- City of Cleveland, City Directory, 1858. ↵

- Cleveland Leader, November 23, 1876. ↵

- Cleveland Directory, 1864-1880, Residential and Business Sections. ↵

- Annals of Cleveland, Court Record Series, 1875-1877, Cuyahoga County, Volume X. Also, City Directory, 1874-1907. ↵

- City Directory, 1890-1919. ↵

- Josef Barton, Peasants and Strangers (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1975) pp. 52ff. ↵

- Charles Coulter, The Italians in Cleveland (Cleveland: 1919) p. 17. ↵

- Charles Ferroni, The Italians in Cleveland: A Study in Assimilation. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of History, Kent State University, 1969, pp. 121ff. ↵

- Nationalities Directory of the City of Cleveland (Cleveland: 1974). ↵

- "Report of the Emigrant Police" in the Annual Report of the City of Cleveland, 1913. ↵

- Ibid., p. 1481. ↵

- Ibid., p. 1484. ↵

- Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 23 and November 5, 1900. Also cited by Wellington F. Fordyce, "Nationality Groups in Cleveland Politics," The Ohio State Archaelogical and Historical Quarterly, XLVI, 1937, 109-147. ↵

- Annual Report of the City of Cleveland, Department of Welfare, 1915, p. 1435. ↵

- Much of the information on the ethnic groups in the Hiram House settlement was obtained from John Grabowski's unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation on the settlement entitled, Social Settlement in a Neighborhood in Transition: Hiram House, Cleveland, Ohio, 1896-1926, Department of History, Case Western Reserve University, 1977. Mr. Grabowski graciously permitted me to have access to his dissertation prior to its final form. In addition he has proven to be an invaluable asset in researching this monograph at the Western Reserve Historical Society where he is the Ethnic Archivist. ↵

- Neighborhood Visitor's Report, Hiram House, February, 1915. ↵

- Ibid., 1912. ↵

- Grabowski, Op. cit., pp. 240ff. ↵

- Ibid., pp. 240ff. ↵

- U.S. Census, 1940. Census Tracts I-1 to I-9 (Cleveland's Big Italy). ↵

- Coulter, Op. cit., p. 11. See also Daniel Gallagher, "Different Nationalities in Cleveland" series in the Cleveland Press, December, 1927. ↵

- See the front page article on Carabelli and the Broggini brothers in La Voce, April 22, 1911. ↵

- Coulter, Op. cit., p. 17. ↵

- For a more extensive analysis of the St. Rocco's Italian community see Karl Bonutti and George Prpic, Selected Ethnic Communities of Cleveland: A Socio-Economic Study, 1974, pp. 117 ff. ↵

- Much of the information on the religious and cultural aspects of Italian ethnicity was furnished by Richard Mileti, a life long student of Italianita in Cleveland. ↵

- For a concise treatment of St. John's Beckwith Church see John Vande Visse, Jr., The Protestant Church in the Predominantly Catholic Nationality Area, M.A. Thesis, Department of Sociology, Western Reserve University, 1948. ↵