Part III: The Italian Community of Cleveland

Chapter 9: Italian Families, Festivals and Foods

Of all the fascinating phenomena associated with ethnicity none has had a more profound effect on the shaping of Italian-Americans than the family. Without exception writers from Barzini and Puzo to Cambino and Greeley have been enchanted by the domestic lives of Italo-Americans. To understand the Italian one must understand the family. It is as simple as that.

From the various accounts of the domestic relationships of the Italo-American certain basic characteristics have emerged concerning the family. But before investigating these characteristics a word of caution should be inserted. Much of the writing on the Italian American family has been sprinkled with nostalgic distortions which may give incorrect impressions about ALL Italian families. What each narrative often deals with is a particular family situation, and the impulse to generalize about Italians has become irresistible. This is not the case and should be kept in mind.

Perhaps most importantly these domestic histories usually relate to first-generation families who would naturally maintain much of the cultural tradition of Italy. What will be described in the following pages would be associated with such first-generation families who would perhaps have much in common with families living in Italy. It would not necessarily apply to second-generation Italians and conceivably would have little relation to third-generation children.

Hence to speak of Italo-American families we must properly speak in traditional terms with usual reference to first-and perhaps second-generation Italians. Beyond that stage some of the traditional emphasis has disappeared through the acculturative and assimilative processes. And with it has come the weakening of the basic unit of Italian ethnicity.

For the purpose of comparison we should examine the family structure as it exists in Italy, especially in the southern regions. For centuries the first source of power in that country was the family unit. Indeed it has been proposed that Italy should be described as nothing more than a mosaic of millions of families. In order to survive and improve themselves during periods of invasion and occupation by Austrians, Spanish, Arabs, French, Normans, and Germans, the Italians relied solely on their famiglia. One of the reasons why the governmental structure in Italy has always been unstable at best is due to the belief that all external political institutions, foreign or Italian, are a threat to the family order and must thereby be rendered useless through systematic anarchy!!! Governments topple, invaders come and go, but the family remains.

And what is the composition of this family, this historical bulwark which has to be maintained at all costs? In the first place it was and still is patriarchal in form but in no way an absolute monarchy ruled by the father. Usually all unmarried children reside in the home and the major life decisions are made for the betterment of the family unit, not of the individual.

In the Italian setting the family is stationary with a strong sense of group stability. Everyone who is able works for the family. In fact, along these traditional lines, the unmarried sons usually give their paychecks to their mother who in turn gives them an allowance. In many instances this practice is still carried on in American-Italian families.

One of the myths surrounding the Italian family is the dominance of the husband as absolute ruler of the home. Of course the father does have a high status, but the wife is the center of the family and usually has the last unspoken word. As the saying indicates, “In Italy the men run the country. . . but women run the men.” One should not be deceived by outward appearances which often have little to do with the actual workings of things.

To estimate the importance of women in Italian society one need only listen to the music or visit the churches to perceive their influence. In what other country are hundreds of songs dedicated to “mamma”? Where else do burly workers cry out to their mamma when they are in pain or are experiencing some difficulty?

In the religious sphere La Madonna has as many churches dedicated to her as to her Son. National Shrines to Mary such as Madonne di Pompei, di Loreto, del Rosario, del Carmine, del divino Amore proliferate throughout the country. During each month at least one day is devoted to Mary, and she is given May entirely as her special month. In Italy children are taught that Jesus was Jewish but they somehow reach the conclusion themselves that Mary was Italian!

Several general statements can be advanced as to the internal workings and external interactions of the Italian family unit. In the first place the family is usually bilaterally extended; bilaterally meaning that descent is reckoned through both mother and father; extended refering to the potential for developing of strong ties outside the nuclear family. Thus one “typical” family would consist of father, mother, children, grandparents, uncles, aunts, and up to third cousins on both sides.

Supplementing this circle of family was the institution of Comparaggio, the systematized selection of those outsiders who were admitted to the family circles. These intimates were literally “godparents” but not in the religious sense of “standing up” for a child at baptism. Compari (male) and Commare (female) were highly respected close friends of one’s own age and considered part of the family. Older Compari would be called zio (uncle) or zia (aunt), or padrino, even though they would not be blood related.

One’s “godfather” or compare was given the same respect as one’s parents, consulted on important matters, and his advice heeded. Yet the relationship was not to be as deep as to one’s own brother or parent. In any clash of interest blood ties always took precedence. This was part of l’ordine della famiglia, the unwritten but all-demanding set of rules governing the family.

The social value of compariggio was considerable. It assured the family’s welfare in an unsure environment. It also maintained the old and destitute within one’s family without the assistance of outside agencies. This is why Italian-Americans have rarely turned to the government for assistance but always to the family.

Jacob Riis, writing at the turn of the centry, noted that immigrant pauperism was highest among the Irish, then native Americans, Germans, etc. Italians made up less than 2% of those requiring assistance. In Cleveland for forty years (1874-1914) Italians were consistantly among the groups requiring the least amount of poor relief. Is there any wonder why Italian-Americans today, although labeled “racist” and “reactionary” view public welfare systems as shameful and distasteful?

The most destitute condition within the Italian society was to be without a family, to be a scommunicato. This status was reserved for those who had violated l’ordine della famiglia either by trechery or scandal. In Sicily to be scommunicato was to be un saccu vacante, an empty sack, a nobody mixed with nothing. Expulsion from the family had borrowed a religious term and given it a secular application.

If being within a family held so much meaning and required so much loyalty, outsiders (stranieri) were literally aliens to be exploited and ignored. The isolation of the south required only one allegiance. All others — church, state, political parties, employers, etc. — demanded and received little recognition.

Because of its insularity the traditional Italian family provided the necessities of life or at least a comfortable survival.

Economically all worked for the common good, the fathers and sons in the fields, the mothers and daughters in the home. Education was provided by the parents, the children being trained in their expected adult roles by the parents.

Throughout the centuries of political instability in Italy the family provided the legal basis for the society. Disputes were settled within the family by family members. Warnings to wayward children were never given or taken lightly. Inter-family problems were dealt with by the elders, always mindful of the protection and honor of their family. Those disputes which were not able to be peacefully settled exploded into feuds or vendette which took on the form of local wars.

Perhaps of all the important roles assumed by the Italian family that of socialization was most important. The family maintained the role of psychologist, psychiatrist, marriage counsellor and matchmaker. Why look elsewhere for friends when one had an inexaustible supply of relatives?

Although it was traditionally the family that chose one’s mate, the decision was given the appearance of developing naturally. This was done by strict supervision of young ladies so that well in advance of any formal overtures of marriage a family knew whether or not the merging of the two individuals, not to mention the two families, would be advantageous. Then, and only then, were matters permitted to proceed “naturally” and betrothal accepted. While the parents reminded their children that “matrimoni e vescovati dal cielo son destinati” (marriages and bishoprics are predestined in heaven), it was understood that the initial choice of the partner was carefully managed by the family.

What has been described was an intricate and oftentimes demanding domestic system which grew and maintained itself out of necessity in the Italian peninsula. However, as this kind of organization was uprooted and transplanted to the urban setting of North America, a different pattern emerged. The myriad demands of the acculturating society attacked the very roots of the extended family, creating a cultural shock few immigrant groups have experienced.

Friction between the first and second generation Italian family in America was soon created. The intimate relationship of the extended family was broken in the Italian ghetto. The primary status of the father was undermined by both the children who could speak English and his wife who oftentimes worked outside of the home and earned more than her husband through skilled millenery work.

One of the most serious gaps between first-and second-generation Italians was the relationship between the children and parents. In the first place marriage partners were now selected from the available prospects, hopefully from the same region in Italy but certainly not compari. Although they would still be Italian the marriage partner would not necessarily reflect the values of the traditional Italian home. Indeed, the marriage of two second-generation Italians often resulted in rejection of the via vecchia and affirming the new ways of America at the expense of the extended family concept.

As the second-generation children attended the public schools and developed a widened interaction with American culture they had to exist in two worlds. They loved their families but were expected to retain beliefs and practices no longer applicable to their urban environment. They were to go out into the world but not become part of it. The culture that the first-generation immigrants held out to their children was inappropriate for adaptation in the New World.

Indeed, the children often became the teachers of the adults, a reversal of roles which was viewed as humiliating by the parents. A poster published by the Cleveland Board of Education and the Cleveland Americanization Committee in 1912 shows a child explaining the A B C’s to his parents. The youngster was to lead his babushkaed mother and moustached father into the schools to learn English and the American way. What impact this must have had upon the Italian family can only be assessed in terms of enrollment in the schools and for the Italian males at least such enrollment was very low.

No better example of the anguish of the acculturation process can be offered than the effect of the public school upon the family as the sole source of authority. If nothing else, school introduced a rival to parental rule. Swiftly the teacher and the school’s codes competed with the authority of the parent and encouraged the child to reject his ethnicity while striving to achieve only middle class American values. The concept of the Melting Pot was dispensed through the classroom.

From the blond-haired, blue-eyed models of the class texts children soon came to believe that their parents were inferior to Dick and Jane’s parents because they did not resemble the models put forth by the books. Much of the educational process was false, having nothing whatsoever to do with the experience of the child. To be different was to appear wrong, and a major cultural adjustment was demanded.

This cultural schizophrenia was to be the legacy of the second-generation Italian American. At home the child spoke and acted as an Italian. Outside he was to be someone else. Ultimately the world of the immigrant would be rejected almost totally by these Children of Columbus with a specific rejection of the extended family concept.

As some of the first-generation Italian children came to denounce much of what was the traditional Italian lifestyle in their quest for identity within the American culture, the ultimate barrier between the generations, that of marriage selection, was erected. A study conducted in 1935 in New York City indicated that between Italo-Americans under 35, i.e. those children of the immigrants, and those over 35, a deep rift had developed. On the question of arranged marriages 99% of those under 35 disapproved. Those under 35 also minimized the importance of large families, the supreme role of the father and the domestic role of the mother. The second-generation Italian family in America was thus characterized by deep intergenerational conflict which would lead to the rejection of the traditional domestic structure.

The second-generation family or those groups either born in America of Italian-born parents or who had themselves been brought here at an early age, would aprticipate in a further disintegration of familiar values. From the few studies available it can be asserted that second-generation Italo-Americans could be characterized by the general weakening of their Italian ethnic ties as they attempted to accelerate the process of assimilation. This family type moves from the ethnic neighborhood into more “respectable” locations. The use of Italian in the home is rejected. Names are Americanized in some instances and Italian cuisine is retained only for holidays or special occasions. Usually this segment of the second-generation Italian have successfully adapted to American society and are basically estranged from the via vecchia.

The third-generation Italian American family has received scant attention even from official sources such as the Federal Census Bureau, which does not record third-or fourth-generation ethnic groups. Among this section, to which many Italo-Americans now belong, most of the traditional values have been lost. The third-generation male is most likely to have crossed ethnic lines in the choice of his spouse. The third-generation Italo-American female in turn is married to a man who does not see himself as the sole authority of the family. Marital roles are occasionally interchangeable, both mother and father taking responsibility for cooking, cleaning and child rearing.

Values seem to have also changed in the third-generation Italian American family. The family is not child-centered and decidedly oriented towards education. The family will normally be small, with only a very few reminders of traditional domestic life remaining and those usually reserved for special occasions. Any reminders of ethnicity usually must be brought into the home, for they do not naturally exist in many families.

And yet a curious phenomen has been taking place among third-and fourth-generation Italian-Americans. It is in this very group, secure in their place in society as individuals who have “arrived,” that a reawakening of ethnicity is becoming evident. This symbolic return to their Italian heritage is manifested in their interest in Italian foods, cuisine, travel to Italy, and similiar experiences. A few are ardent advocates of Italian organizations or the reading of Italian-American magazines such as Identity or Italian American.

Their attachment to the via vecchia may be indicated by their return to some of the external rituals associated with the extended family. A 1967 study conducted by the National Opinion Research Center revealed that of all the major ethnic groups Italians still had the highest percentage of those who were maintaining physical contact with their parents. For example: 40% of those polled live in the same neighborhood with their parents; 33% live in the same neighborhood with their children; while 24% live in the same neighborhoods with their in-laws. Seventy-nine percent of Italians saw their parents weekly and visited their children, and 61% saw their children at least once a week. These figures would indicate that in recent years there has been a return to some of the traditional family values, at least as they pertain to physical closeness between children and parents.

A recent poll (April, 1977) conducted by Identity magazine attempted to determine the Italianita of its subscribers. It was assumed that the vast majority of these readers would be Italo-American, and the initial returns indicated that the median age was 45 years old with an average income of $24,000.

Of interest were those statistics relating to the family; 81% of those polled were married or widowed, 85% spoke Italian and “ate Italian” at home at least three and a half times per week.

The negative impact of the Americanization process has been significant when applied to the Italian-American family. The classic example of this adverse influence is the case of Roseto, Pennsylvania, a town of 1,600 people, 95% of whom are Italian-Americans. During the 1960’s researchers from the University of Oklahoma arrived to determine why there were so few heart attacks among these people despite the fact that they ate a rich, spicy, high-cholesterol diet. No one under 47 years of age had had a heart attack and the average Rosetan ate more and lived 10 to 20 years longer than the average American. Was it in the water, the air, the wine, or was it psychological?

Ten years later, the miracle of Roseto was over. In 1972, the heart attack rate of the town rose to three times the national average. The reason. . . the rapid rate of “Americanization.” And according to the head of the University of Texas medical research team who have been investigating Roseto since 1961, the cause is definite: “In Roseto family and community support is disappearing. Most of the men who have had heart attacks here were living under stress and really had nowhere to turn to relieve that pressure. These people have given up something to get something and it’s killing them.”

Perhaps this reawakening of Italian ethnicity is only a curiosity, especially as it involves the traditional family structure. It certainly is not in tune with today’s liberating lifestyles and could be considered “square” by many standards. But when the values and traditions of kinship relating to the extended family are juxtaposed to the current state of marriage in America and the status of the American family, the ordine della familia may prove to be more enticing and rewarding than first imagined.

Italian Foods

Within the Italian family food is much more than just the habit of filling one’s stomach. It has taken on the appearance of a ritual of the highest order. In fact the sharing of a meal oftentimes has become a symbolic communion, permitting one to pass from the status of a straniero to an acquaintance by the mere taking of wine or coffee together.

Each meal has its own significance. The noon meal or collazione was usually eaten together by all family members when the group worked near the home. In America this feast came into conflict with the American school system. It was unthinkable for Giovanni or Maria to eat lunch anywhere except with the family. But the schools offered subsidized “balanced meals” in school and through this incentive exacted one more tribute to the acculturative process.

I can remember that as late as 1974 one of the major “problems” at Collinwood High School was the keeping of our students in school during lunch. In this Italian community lunch was eaten at home; this custom was interpreted by the administration and faculty as just another attempt to “escape” their authority. It created a cultural gap which to this day has not been bridged at the school.

Pranzo, or dinner, also was eaten together with the family. Occasionally godparents and honored friends were invited. Unlike their American peers, Italian children rarely ate at their friends’ homes because that would infringe upon the family unit. The traditional family meal was to play a significant part in maintaining ties with the old world. The breaking of this tradition would assist in the acculturation process and weakening of the family structure.

And what of the meals themselves? In the first place, since the majority of Italians immigrating to America were from the South of Italy, the cuisine of their regions naturally predominated at the Italo-American table. The major differences between northern and southern Italians is their staple eating habits. In the northern regions polenta or cornmeal and risotto (rice dishes) are the foundation of the meal. In the south an infinite variety of pasta are the basic foods. Indeed northern Italians are often labeled polentani, “polenta eaters” by the southerners while some of the sobriquets offered by the northerners about the southern Italian are unprintable.

Pasta has become increasingly the basic dish familiar to all of Italy, from the Piedmont to Sicily, Tuscany to the Abruzzi. It is mostly a myth that Marco Polo first introduced spaghetti from the Orient in 1292. There is abundant evidence that pasta was being eaten in Italy during Etruscan times. Sicilians were devouring strands of dough at the time of the Arab invasions, about 800 A.D., while ravioli and fettuccini were known during the early middle ages.

That noted Italophile Thomas Jefferson imported the first pasta-making machine to his beloved Monticello in the 1780’s. His spaghetti was approvingly eaten by family and friends alike, although an early American recipe (1792) called for boiling the pasta in water for 3 hours then for another ten minutes in a broth, then mixing it with bread in a soup tureen!!!

Italians are emotional when it comes to their foods, especially pasta, each region, commune and city declaring its variety to be the best. The writer Giuseppe Marotta has delivered an extremely theatrical but typically Italian comment on this subject. Writing of the Neopolitans’ love for pasta he remarked: “He who enters paradise through a door is not a Neopolitan. WE make our entrance into that heavenly abode by delicately parting a curtain of spaghetti.”

Each of the regions of Italy has produced its own specialities. That which we normally refer to as “Italian” cooking is really only the cuisine of the southern regions for the most part. From Lombardy rice dishes such as Risotto mixed with saffron are common. Indeed rice is mixed with almost any conceivable food such as Omlette di Riso, Riso al Salto (rice fried in butter) rich with mushrooms, even pumpkin and rice.

In the Veneto maize was first introduced in the early 16th century and the first polenta was created. Polenta is eaten with a variety of meats, game and fish dishes and is common to Verona, Padua, and Venice. Along with polenta, Baccala, or sun-dried salt cod, is a favorite of the Veneto as it is among Italian-Americans.

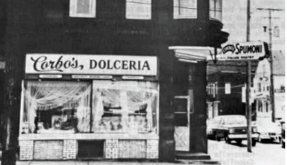

Southern Italian cuisine has had the most impact upon the American palate. Pizza from the Naples area needs no introduction to the Americans who consume 1.75 billion pizzas annually. The kind of pasta common to Americans is “pasta al dente,” “to the tooth.” This variety is slightly resistant to the bite, in other words, not overcooked. Sicily offers the sweet desserts such as cannoli, those crisp shells of pastry stuffed with ricotta cheese or cream. Gelato or ice cream also originated in Sicily, the invention of Procopio Catelli who introduced this treat to Parisian society in 1630.

Italy has shared other foods with America besides pasta and pizza. Such vegetables as broccoli, fennel, zucchini, and artichokes and herbs like rosemary and oregano were introduced from the Italian tavola to the American table. Lasagna, manicotti, chicken cacciatore, antipasto and minestrone are common dishes on American tables and in American restaurants. And I haven’t even mentioned the cheeses from Parmesan to Fontinella, Bel Paese and ricotta to mozzarella. And lest we forget, the hero, torpedo, submarine and grinder are only variations of the Italian-American sandwich.

Some Italian foods are not common to Americans but do have interesting names. A few of the more exotic ones are:

Saltimbocca (Leap in the mouth) delicately fried veal Stracciatella (Little Rag Soup) dumpling soup Ossobuco (Hollow Bones of Liguria) braised veal shin Calzoni (The Trouser Leg) folded-over pizza Aragosta fra diavolo (The devil’s lobster) lobster Mozzarella in carrozza (cheese in a carriage) Cappelletti di Romagna (Little hats of cheese) Orecchiette al Pomidoro (Little ears of cheese).

Like most ethnic groups Italians have special foods for the various religious holidays during the year. Christmas is traditionally the holiday of a variety of sweets such as the Panettone or Christmas cake sold at most import stores in the Cleveland area. It is made of flour, raisins, rum and a variety of other ingredients. It is said to have been originated in Milano by a baker named Toni, hence the name Toni’s bread, “Pane Toni.”

Easter (La Pasqua) is a day of centuries-old tradition and culinary ecstasy. Perhaps the most common foods associated with La Pasqua are Abbacchio or spring lamb, and porchetto, or roast pig. A typical Easter meal would consist of an antipasto, abbacchio, ravioli and for dessert a torte or the traditional Pastiera di Grano, or Easter Wheat pie. In some parts of Italy blessed palms are inserted into the filling of cheese, candied cherries, eggs and grain before it is baked.

In the same breath with foods we must also mention wines for both are synonymous with life. “Un giorno senzo vino e come un giorno senza sole. . .” (“a day without wine is like a day without the sun”) is an authentic Italian expression which has been modified by American advertising to refer to orange juice. But the thrust of the expression remains the same. Wine is a necessity at the tavola of the Italian family, a natural food rather than a primary source of inebriation.

There was no age restriction placed upon drinking wine, much to the chagrin of the American teachers, social workers, and those other “officials” who visited the immigrants and witnessed the regular drinking of small amounts of wine by children. Usually the wine had been diluted with water for the young; but they were nonetheless becoming acquainted with the taste of the drink.

It is with this experience with wine that Italo-Americans have traditionally been raised, in an environment which considers wine as a natural food to be enjoyed, not to be feared or locked in a liquor chest. I have never personally known an Italian who was an alcoholic, although I assume there probably are some. I would be surprised if there would be many. For Italians, the mystique surrounding alcohol has been removed through the natural teachings and habits of the family.

Added to this was the continued association of food along with wine and soon a good habit had been formed. Today Italian-Americans raised in the traditional family naturally connect eating and drinking. While Americans usually drink martinis without food for the primary inebriating effect, Italians drink chianti as a tangy potion pleasing to the palate and stimulating to the gastric juices.

Some of the world’s finest wines are produced in California by Italian-American families rivaling the chateau vintages of Bordeaux and Burguandy. An estimated 43% of America’s wines are produced by about 60 Italo-American families, with Ernest and Julio Gallo accounting for 34% of the nation’s wine sales. The Sabastiani winery sold over 1,250,000 cases of wine in 1976 through 250 distributors across the country. Along with the Italian Swiss Colony, the other major Italian producers in California are the Martinis, the Foppianos, and the Pedroncellis from Tuscany, Genoa and Lombardy respectively.

Italian wines are as diversified as the regions of Italy. Some of the more popular Italian wines gracing the world’s tables are Lambrusco, the red wine originating in the Romagna. Chianti, another red wine, comes from Tuscany and is the universally accepted drink with pasta. The wines of Verona, Valpolicella and Bardolino are among the most popular and most expensive of the imported Italian wines. Asti Spumante, the sparkling wine of Piedmont, has been widely known as “Italian Champagne” in this country although it costs about half the price of French champagne.

Amaretto and Galliano have gained a wide acceptance by Americans as versatile after-dinner liquors. Amaretto dates from the early 16th century. It was concocted by a love-struck widow for a painter, Bernadino Liuni, out of apricot pits, alcohol and almonds. Galliano, the golden sweet liqueur of the south, is a popular after-dinner drink in American homes and supper clubs.

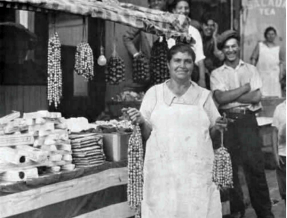

Family, foods and wines come naturally together with a great deal of gusto during feasts. Processions, festivals, children dressed in white, bands, and endless tables of food mark these special days dedicated to the various regional saints of Italy. In New York City the tenement-lined streets of little Italy along Mulberry Street erupt into a 10-day, 9-night fair honoring San Gennaro, the patron saint of Naples. Beginning on September 19, this feast attracts thousands of tourists from all over New York to partake of the carnival atmosphere.In Cleveland, August 15 marks the Feast of the Assumption and the Murray Hill Community announces the beginning of a weekend festival. After High Mass at Holy Rosary Church, a procession of the Virgin is begun with Her statue carried through the streets while money is pinned onto the statue by thousands of persons in the crowds. The procession is climaxed by a blast of fireworks, after which the marchers eat a traditional meal of cavatelli with sauce prepared by the parish women.

The Feast usually begins on August 12 and concludes on the 15th, although some changes have been made in recent years to have the festivities fall on a weekend. The entire operation takes the efforts of about 300 persons who run the amusement rides and games of skill and cook the pizza and cavatelli. John Peca, who operates a sign shop at Mayfield and Murray Hill Roads, has been the program chairman for the last twenty years. Although other festivals are held in other Italian communities across the country, Mr. Peca explained that the Feast of the Assumption is unique to Cleveland’s Little Italy because it was special to the people from Campobasso province, the region from which many of the early immigrants to Murray Hill came. Of what significance is the Feast to the Italian-American community of Cleveland’s Little Italy? Financially, it has made important contributions to the operation of the church and school. According to Fr. Valentini, Pastor of Holy Rosary, it may someday help finance a senior citizens home in the neighborhood and hopefully draw back many of the younger families into the neighborhood.

But the other important aspect of the Feast is its ability to elicit an ethnic response from the Cleveland community. As John Peca observes, “Each year the festival becomes bigger and better. But most important it gives us all a sense of pride and accomplishment.” It is on this feeling of togetherness that the real traditions of Italian ethnicity is based.