Part I: Old World Origins

Slovakia During Medieval Period

Devastation Looms

During the 13th century, Slovak lands suffered the ravages of the Tatar invasions. Their hordes devastated all the resources of the land, destroyed churches, and slaughtered the Slovak population, especially the young and the aged. The able-bodied were carried away as prisoners. Those who could escape, hid in the mountains and caves. After the Tatars had their fill of cruelties in these lands, they left. The Slovak survivors came out of their hiding places hardly able to identify the villages and towns in which they had lived before this terrible ordeal. Only the ruins marked the sites of their communities.

Feudal Times

Were this not enough, after the warlike Tatars abandoned these desolated regions, foreign barons further exploited and oppressed the Slovak lands. In time, however, the Kingdom of Hungary was itself torn by internal disorder and numerous political upheavals. Frequent wars tipped the scales among the various contending forces — Hungarian, Czech, Austrian, German. The local and foreign nobility snatched at every opportunity to claim increasing power appropriating control of various Slovak districts.

An Enterprising Slovak, Matthew Čák

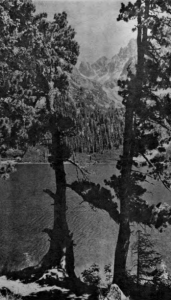

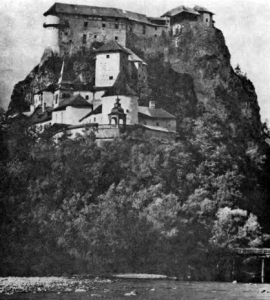

One such noble was Matthew Čák (Chak) of Trenčín (Trenchin). He had attained such power to earn the surname “Lord of the Váh and the Tatras.” He capitalized on every opportunity to strengthen his position by arrogating lands and estates to his ancestral holdings and by compelling other nobles to acknowledge and accede to his sovereignty. The peak of his power was reached with the capture of Trenčín Castle in 1299. In this fortress he established a court with all the appointments and retinue of a functioning sovereign. By 1301 Matthew Čák established an independent state of Upper Hungary controlling an expansive territory that reached from the Morava River to Spiš (Spish) and from the Danube to the Tatra mountain range.

Therefore, Matthew Čák seems to exemplify the innate aspirations and capacity of the Slovak people for self-rule in a successfully operational political state. As a ruler he personified a kind of Slovak national ideal at the time when the notion of nationalism had not yet crystallized as such. He had the inborn gift of discerning favorable historic circumstances and the leadership charisma to act in situations that might have deterred a lesser man, even though he may have been motivated by personal aggrandizement.

As “Lord of the Váh and the Tatras,” Matthew Čák ceremoniously held court at Trenčín Castle in the best of ruling practice and tradition. Here he presided and received visits of state of numerous vasals exercising all the prerogatives of an absolute ruler. He maintained an independent army, negotiated matters of diplomacy and foreign exchange with neighboring nobles and established a mint in Nitra to coin money for his realm. (See pg. 34)

His power lasted for 20 years and the splendor of his court and the magic of his name became proverbial among the Slovaks.

Charles Robert, the Italian contender to the Hungarian throne, displayed a mixed attitude toward Matthew Čák and his undeniable power. At first he was inclined to resist him, then he decided to honor him with distinctions and finally he withdrew his proffered promises of recognition. A series of struggles followed and in the course of years a number of nearby lords were overcome by Charles Robert. Because of tremendous odds of manpower that were pitted against him, Matthew Čák himself suffered some setbacks and lost some of his territory. Trenčín Castle, however, remained his stronghold and he continued to rule over a diminished region until the end of his life in 1321.

Charles Robert of Anjou

After the death of Matthew Čák, Charles Robert of Anjou, the new Hungarian ruler (1308-1342), extended his dominion over Slovakia absorbing it into the kingdom of Hungary. This period however, is characterized by a degree of economic development in the Slovak lands. Charles Robert found that the strategic location of Slovakia made it a favorable site for diplomatic events. In the city of Trnava he concluded an alliance with King John of Bohemia (1327); in Trenčín he held a friendship parley with John’s representatives and with Casimir the Great of Poland (1335). In Košice and Zvolen he hosted Polish-Hungarian meetings of historic importance (1382).

Sixteenth to the Seventeenth Centuries

Hussite wars (1421-1434) that originated in the Czech lands repeated the catastrophic devastation of the earlier Tatar invasion in a series of horrible predatory penetrations into Slovakia.

During the following centuries the Turkish power humbled Hungary and Buda (the capital of Hungary) became the center of Turkish domination. While the Magyar portion of Hungary fell under Turkish rule, Slovakia remained under Austro-Hungarian empire. Bratislava in Slovakia became the vital center of political and cultural activity. The Hungarians brought to it their key government offices, made it their coronation city and convened sessions of the Parliament either in Bratislava or in Trnava.

Catholicism Threatened

After Esztergom was seized by the Turks in 1543, even the archiepiscopal and Catholic center of Hungary was transferred to Trnava in Slovakia. For the next three hundred years, Trnava continued to be the center for all significant functions of church and state. When religious upheavals occurred in the 16th century, and the Lutheran and Hussite movements produced a national crisis, church synods (meetings of bishops) were convoked in Trnava by Archbishop Nicholas Oláh, primate of Hungary. Under his leadership an effective trend was launched to bring about fruitful peace and general understanding among the two nationalities.

Cardinal Pázmány

In the Catholic Reformation movement among the Slovaks, the most efficient antidote to Protestantism was the reorganization of the school system and the influence of humanism. Archbishop Oláh was instrumental in having the Jesuit Fathers come to Slovakia in 1561 and in having them conduct a college in Trnava. Their presence in Slovakia also marked the development of a broader scope of missionary activity in a number of Slovak cities. However, a disastrous fire destroyed the college in 1567, and shortly after that, the Jesuits left for other missionary fields. From the time of this departure they did not return until Archbishop Peter Pázmány (1616-1637), who later became a cardinal, gave new impetus and more enduring success to the Catholic revival in Slovakia. Endowed with a brilliant mind and committed to spiritual values, Cardinal Pázmány impressed not only the common man, but the nobles and the learned as well. Under his inspired leadership, many Slovak nobles were moved to return to the Catholic faith and many expropriated church properties were restored.

Another notable achievement of Cardinal Pázmány was his comprehensive program of youth education based on solid philosophical, theological, and humanistic principles. The Jesuits were invited to organize and conduct a seminary in Trnava. At the University of Vienna a special college “the Pazmaneum” was established for gifted clerical candidates from Hungary. Special boarding schools and high schools were provided and a native university was founded in Trnava (1635). This center of higher learning had a more successful history than did the earlier university, and it offered a much richer curriculum as well, greatly promoting the cause of religion and culture.

Trnava University was later able to expand these activities through its own university press which was very active in publishing scholarly works in all the languages that were used by the multilingual population of Hungary.

Piarist and Franciscan priests also engaged in educational endeavors of many kinds under the sponsorship of Cardinal Pázmány. and a great surge of religious and cultural vitality appeared throughout the land. These trends waxed strong as long as peaceful conditions prevailed but political problems, originating outside the country, especially those caused by the Turkish menace, blighted this promising resurgence in spiritual and intellectual activity.

No Respite from War

Slovak territory repeatedly became a harrassed battleground that was devastated by the invading Turks as well as by plundering defending armies at least until the Turks were finally driven out of the country in 1718. Later, Slovak lands were again the scene of fierce battles during the Thirty Years War and they were subjected to all the ruthless ravages of a battleground. In repeated warring engagements, Slovakia suffered the fate of a pawn of battle as it passed from the keeping of one aggressive army to another, the shifting fortunes of war favoring now one side, now the other. The people suffered indescribably, and it is surprising that in these vicissitudes of the times, they did not lose their national identity.

Juro Jánošík

Under the Habsburg system which followed the Turkish domination, the peasantry had no brighter prospects. As their sufferings mounted, some of the hardier and more venturesome subjects dared to lash out against their hopeless lot. Groups banded together as brigands, hiding on the mountainsides. From time to time they unexpectedly swooped down out of their seclusion to raid the strongholds of the well-to-do and to intercept the coaches of barons traveling on the highways and despoil them of attractive goods. They had committed themselves to the policy of “robbing the rich to help the poor.” These mountain boys became legendary heroes celebrated in folk tales, ballads and songs. Juro (George) Jánošík (1688-1733), the best known of them was hailed among the oppressed as the champion of social justice and defender of the rights of the common man.