Part I: Old World Origins

Slovak Revival, Language and Literature

Nationalism

Quite early in the 17th century expressions of national consciousness began to rock nationality relationships in Hungary. This wave of newborn ethnicity was prompted by the Magyar assertion of nationalism as well as by influences from the French Revolution that unmistakably made themselves felt throughout Europe. Since it had been an age-old practice for Slovak families of means, and many of the middle class too, to send their sons to German schools for advanced education, a considerable number of Slovaks came in close touch with the burgeoning German national life. These students, in turn, became the natural bearers of progressive ideas and ideals into their native land.

Ján Hollý

Shaped by such influences, new patriots emerged. Among them are individuals who proclaimed allegiance to their homeland like Alexander Rudnay, Cardinal and Primate of Hungary, who asserted: “I am a Slovak, and though I am installed in Peter’s Chair, I will remain a Slovak.” There was also the immortal Slovak priest-poet of the classical school, Ján Hollý, who created Svătopluk, an epic in twelve cantos which glories in the heroic aspects of a historic Slovak ruler of a bygone age. Holly also wrote Cyrillo-Methodiod, another magnificent work which served to revive a glowing memory of earlier times. These and similar works recalled Slovak ancestors whose example could again enkindle national pride and genuine patriotism as they renewed the hope that a glory which had once declined might yet be revived and perpetuated.

Jan Kollár and P.J. Šafárik

Jan Kollár and P.J. Šafárik likewise became outstanding promoters of the patriotic revival and of Slovak nationalism. Šafárik is often remembered as the founder of scientific Slav studies and his most notable contribution is embodied in the scholarly work Slavic Antiquities. Kollár became famed as the Slavist who synthesized the concept of Slav unity and advocated cultural and literary reciprocity with wholesome respect for each Slav nation’s political and cultural independence. Simply expressed, Kollár advocated a cultural advancement rather than military conquest as a means to Slavic emancipation. He took pains to examine the fate of all Slavs reduced to subjection and to propagate a humanistic and spiritual bond among the Slav peoples regarded as brothers in the family of man. He supported his theories by references to ancient beliefs and to the works of many earlier Slav writers of Polish, Russian, and Czech background. He appealed to Christian teaching and the tactic of peaceful effort. His eloquence, his logic, and his powers of persuasiveness won many adherents to the cause of “brotherhood among the Slavs.”

Kollár’s outstanding creative work is Slávy dcéra (The Daughter of Sláva), a unique poem of over six hundred sonnets wreathed into an artistic cycle. It can be regarded as one distinct contribution in the cultural field with which Kollár gave incontrovertible substance to his ideas.

These pan-Slavic nationalistic theories found expression in a gathering of 350 leaders at a Slav Congress that convened at that time in Prague. Ironically, Kollár himself was not permitted to attend but at the Congress his colleague P.J. Šafárik greatly inspired those who attended the sessions. The Germans who aspired to a unification with Austria-Hungary were irritated by the Congress. At first they ridiculed the Congress proceedings and later even used military force to quell such pan-Slavic tendencies. Yet, all this in no way countered the spirit of the Slavs who continued to repudiate assimilation by the Germans and the Magyars, resisting force with force.

Philological Reforms

A most important factor in the development of national awareness was the movement of Slovak intellectuals to popularize the native language as a pre-condition for preserving a strong national identity. This conviction slowly gained increased acceptance and permeated many walks of life.

Anton Bernolák

The earliest language program with positive results in this new period was initiated through the historic philological reforms of Anton Bernolák. He codified a standard form of literary expression that would tend to unify the Slovaks who spoke in a great variety of dialects. In 1787 Bernolák published his scholarly work Philologico-Critical Dissertation on the Slovak Language. He further formulated the first rules of Slovak orthography, published a Slovak grammar in Latin, and compiled his monumental work, a six-volume pentalingual Slovak dictionary with word equivalents for Slovak terms in Czech, Latin, German, and Magyar.

The movement to establish a standard language norm for the nation furthered national unification. The literary renaissance that followed enriched Slovak literature through the works of Joseph Ignatius Bajza (1755-1836); the contributions of the leading literary stylist George Fandly (1754-1811); Canon George Palkovič (1763-1835) who produced a translation of the entire Bible and other books into revised Slovak; Martin Hamuljak (1789-1859), and John Hollý (1759-1849) to whom reference was made earlier

Ludov̇ít Štúr

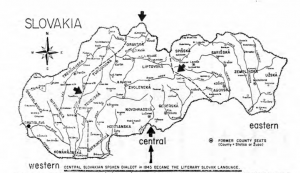

The language reform which was begun by Bernolák was further advanced by Ludov̇ít Štúr (1815-1856). In 1844 he introduced sweeping revisions of standard Slovak idioms by updating Bernolák’s earlier effort. Introducing practical changes, Štúr emphasized the dialects of Central Slovakia as opposed to the Western dialect used by Bernolák. Štúr’s reforms met with an enthusiasm which was, in effect, a reflection of his own spirit. His ardor and leadership inspired many young students and eventually provided the nation with some of its finest leaders.

Štúr and his co-workers turned their attention and their talents to journalism and here happily discovered an even more effective means of disseminating their ideas. Štúr’s closest associates were the Lutheran ministers Miloslav Hodža and Joseph Hurban.

The first published book incoprorating Štúr’s linguistic norms was titled Nitra. It appeared in 1844 and was hailed for using Slovak native expressions. On the other hand, it was also denounced (especially by Kollár and his coterie) for departing from forms of Czech expression because this departure was viewed as action and practice that would lead to greater fragmentation and disunity. Štúr weathered all criticism and he gradually gained general support for his reforms. A surprising number of magazines appeared and a new generation of Slovak poets and authors arose, putting Štúr’s reforms to practical use.

Literary Achievement

The literary “school of Štúr” included poets like Samo Chalupka (1812-1833) whose muse took him to events and castles of earlier times; John Botto (1829-1881) famed especially for The Death of Jánošík; Janko Kráľ (1822-1876), a lyric poet who was personally fond of shepherds and their lore and a patriot whose poetry does not remain on the printed page but burns into his very life.

The most renowned poet among the Štúrists, however, was Andrej Braxator (1820-1872) generally known by his pen name Sládkovič, who produced the tender and artistic romantic works Marina and Detvan. His poetry delineates Slovak characteristics with a great sense of authenticity and assurance. Detvan (The Mountaneer from Detva) is considered the ultimate work of Sládkovič and one of the finest examples of Slovak poetic genius. The lyrics of Sládkovič express deep tenderness and sensitivity with bursts of dazzling fire especially when the lines are suffused with patriotic feeling.

Historical tales and novels also had their share of attention among the writers of this time. Perhaps the best known among them are the works of John Kalinčák (1822-1871) who wrote against a background of Great Moravia, the age of Matthew Čák, the era of King Matthias, the Turkish invasion and closely related periods. He drew many of his themes from narratives told by his grandmother as she reminisced about the great landholders and families of the gentry as she had known them. His crowning work is Reštaurácia (The Election).

There are literally too many writers to discuss here but at least passing notice must be taken of Pavel Dobšinský (1828-1885) who became a diligent collector of Slovak folk tales and folklore. František Sasinek (1830-1912) ranks as an able historian who researched the role of Slovakia in Hungary’s history.

Outstanding Slovak Writers

Among outstanding writers of a later period we must give at least passing mention to these:

Svetozár Hurban Vajanský (1847-1916) a gifted novelist, poet and essayist who concerned himself with many topics, not excluding politics.

Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav (1849-1921) who achieved renown for his volumes of dramatic, lyric and epic poetry. His most highly acclaimed work is Hájnikova žena (The Gamekeeper’s Wife) which is characterized by its melodious celebration of the glories of nature and is hailed for its theme of the moral strength of the Slovak people. In other works, like Gábor Vlkolinský, Hviezdoslav deals effectively with the life and spirit of lower nobility. This poet’s talent was equal to the handling of Biblical themes like Agar, Cain and Solomon’s Dream; he also had the touch to master elements of humor as he did in Bútora and Čútora with its theme that realistically includes a quarrel among peasants; he had the artistic capacity for sensitive lyrical expression comparable to that of Wordsworth in his nature poetry, and he was a successful translator of authors like Goethe, Pushkin, Shakespeare, Petöfi and Mickiewicz.

Vajanský, Hviezdoslav, and Kukučín are a trio of quality writers. Martin Kukučín (the pseudonym of Matej Bencur, 1860-1928) was a medical doctor who found that voluntary exile in South America was kinder to him than were living conditions at home. He excelled in prose, especially as a novelist with excellent character delineation and uncommon skill in plot development.

Societal Beginnings

Literary societies likewise grew apace with this intellectual renaissance. Bernolák, the lexicographer and codifier of the Slovak language, for example, was one of the founders of the Slovak Learned Society (Slovenské učené tovarišstvo), established in 1792 in Trnava to give direction and added substance to revitalized Slovak cultural life. This parent society had branches in Nitra, Rovné, Banská Bystrica, Solivar, Rožňava, and Košice. In 1801 the Society of Slovak Literature (Spolok literatúry slovenskej) was founded in Bratislava to promote publishing programs. The Malohont Learned Association (Učená spoločnosť malohontská) was founded in 1808 and the Banská Literary Association was organized in Banská Štiavnica in 1810. In 1834 Martin Hamuljak founded the Society of Devotees of the Slovak Language and Literature. It was a successor to Bernolák’s Slovak Learned Society.

Preeminent among Slovak learned societies, however, were the Matica slovenská and The Society of St. Adalbert (Spolok sv. Vojtecha).

Matica slovenská was a national foundation established through the organizational genius of Bishop Stephen Moyses in Turčiansky sv. Maetia in 1863, the memorable year that marked the millenium of the coming of SS. Cyril and Methodius to Great Moravia, to Slovakia. Its very title Matica suggests a relationship of filial devotion on the one hand, and maternal nurturing on the other, for the existence of this cultural institute was to stimulate, to propagate and to enlarge the spirit by providing cultural sustenance, the essential life of the nation. It is a scholarly center that had been the hope of Slovak leadership for a long time. Its active program of research and publication, especially in the sense of corporate effort, was stated in the original bylaws: “to foster and support Slovak literature and the fine arts.”

The expanded program of the Matica slovenská includes the promotion of all kinds of artistic creativity, the organization of drives and fundraising campaigns for cultural projects, the founding and development of a central library, and scholarship aid for deserving scholars and artists. Nor did the Matica overlook the needs of the common man, for among the publications which it sponsored are handbooks, monographs and specialized studies for those who were engaged in occupations like fruit-growing, bee-keeping and similar interests.

The prime service of the Matica slovenská, however, was its consistent and effective support of the standardized literary medium which found its way into every village and became rooted among a people whose speech was greatly variegated by dialects and sub-dialects. This bond of unification cannot be overestimated in the history of the Slovak people.

The Society of St. Adalbert was envisioned by its founder Dr. Andrej Radlinský as supplemental to the Matica slovenská. It was established in Trnava in 1870 to function mainly as a publishing house. Annually it provided the Slovaks with tens of thousands of religious books, pamphlets, periodicals and handbooks. Early in its history it formed a Biblical commission which inaugurated and implemented a new Slovak translation of the Holy Scriptures.

Both of these cultural centers exist to this day and they would have a prolific mission in serving the life and the spirit of the Slovak people if they were not severly restricted in their activities.

THE TRENČÍN CASTLE OPEN AGAIN

As of May 1st this year the first reconstructed sector of one of the lorgest castles in Central Europe — the Trenčín Castle in Central Slovakia, has been open to the public. In fact, a busy building activity has been going on in castle premises since 1954. It is gradually being given back its former grandeur and beauty — such as it possessed before being gulled out by fire in 1790. Even though, because of the ongoing archaeological survey and general reconstruction work on the various palaces, only the lower part of the castle courtyard is accessible to the public, a visit to the castle is quite attractive. Of interest is the exhibition of items pertaining to the administration of feudal justice which has been opened by the Trenčín Museum in the former castle dungeon.