Supplemental Articles

ETHNICITY AND POLITICS: THE HUNGARIAN EXPERIENCE IN CLEVELAND

By: Dennis Frigyes Fredricks

The Hungarians, who call themselves “Magyars” colonized the Buckeye Road area on the east side of Cleveland in the late 1800’s and built the proverbial “Little Hungary” that was to be a political force in Cleveland and Ohio politics for the next century. Buckeye Road’s Little Hungary was to produce university educators, Hollywood stars and producers, celebrity athletes, judges and legislators. Cleveland was for Hungarians, what Brooklyn was to the Jews and Boston was to the Irish.

Little Hungary was the complete community from the cradle to the grave. Its sons and daughters were literally baptized in its many churches and buried from its several funeral homes. There they found the butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker, the lawyer, doctor, dentist and accountant, the realtor, grocer, travel agent and insurance man.

Politically the area was potent. By the outbreak of World War I, the Hungarian neighborhood was the equivalent of an entire city ward, the basic subdivision of municipal politics. By the end of World War II, it had grown to two of the city’s 33 wards: the old “16th” and the “29th”.

The twenty-five years that followed World War II, from 1945 to 1970, were Little Hungary’s Golden Era. The Old Settler’s, bolstered by the new refugees escaping the national devastations of the War, and the Revolution of 1956, solidified a powerful bloc in the political composite of Cleveland.

The bloc had one party. They were Democrats. The bloc had one newspaper, the “Szabadság.” The bloc had three Hungarian language radio programs, and the three broadcasters were the best of friends.

With this type of solidarity, the Buckeye Road political machinery elected Hungarian councilmen, one of whom was to be Cleveland City Council President for eleven years. In the early 1960’s, five Hungarian-American judges sat on the various benches of the area courts. The representative to the Ohio General Assembly, was of course, a Hungarian-American.

Non-Hungarian politicians seeking election at the city or county level recognized the importance of the neighborhood’s support and made exceptional efforts to garner the endorsement of the “Neighborhood Fathers.” In time, Buckeye Road became a “de riguer” stop for statewide candidates seeking the gubernatorial or the senatorial nod. Even the late president, John F. Kennedy, amidst the whirlwind campaign blitz of 1960, thought it essential to stump for votes at the annual Moreland Park rally.

The Golden Era spawned the “Night in Budapest” galas which for over a decade were the sparkling cultural extravaganzas drawing stars from Hollywood and political leaders from all levels of government. In its final years, the Night in Budapest was moved from Buckeye Road to the downtown Sheraton Hotel Ballroom, Cleveland’s largest, to accommodate the 2000 guests who came to see Zsa Zsa Gabor, Jimmy Durante, Ilona Massey and Bill Dana, among others.

The overwhelming splendor of the Night in Budapest, and the warmth of the attendees, won many powerful friends for Little Hungary. Its guests included Mayors Anthony J. Celebrezze and Ralph Locher, Congressman Charles Vanik, Governor Michael DiSalle and Governor/Senator Frank Lausche.

During the Golden Era, Little Hungary was a community that worked like a miniature version of Richard Daley’s Chicago. The neighborhood was stable and cohesive, and was rewarded with the finest city services.

Its people were patriotic. They were true-blue Americans. The long honor rolls of Buckeye-boys who died in American uniform in World War II, Korea and Vietnam proved that. At the same time, its citizens were proud of a 1000 year heritage that was exemplified in the parades, processions and feasts, of Buckeye Road. They marched and danced in the streets bedecked with red, white and green bunting, observing the special days of the Hungarian calendar.

The “Fathers” of Little Hungary were quite unlike the titans of Cleveland industry. They were not the heirs of vast fortunes nor the end products of aristocratic social breeding. They were not sent to select schools nor groomed in management training programs. By and large, they were poor boys (and girls) who grew up in the small frame houses and narrow streets of the Buckeye Road neighborhood.

As grades schoolers, they played baseball or soccer in bare feet, in the backlots off the side streets. In junior high school they hawked newspapers, and in high school they made deliveries for the shopkeepers for pennies a day.

They were ridiculed as “Hunkies” by their classmates, passed over for the good jobs by the “establishment” boys from Wade Park, and snubbed by the society girls of neighboring Shaker Heights.

Like the Blacks, they felt a cultural void. “Their kind” was not depicted favorably in the motion pictures, their events were not noted in the daily newspapers, and in general, the mainstream of culture passed them by.

After all, they too were members of minorities and had to try that much harder to attain respectability. They had to be tough to succeed, but had to remain gentle to not lose the common touch. They developed a serious, purposeful demeanor that enabled them to forge ahead at Saturday’s political caucus, but they retained a warm, lovable mischief that enabled them to dance a “csardas” with a six year old niece at the Sunday afternoon church dance. It was this blend of traits, evolving through a unique environment that made the Neighborhood Fathers leaders, and it was the natural talents and abilities of these leaders that built the Buckeye Road political tradition.

Zoltán Gombos. Called upon for political and policy counsel by Presidents, and advisor to Ohio Governors and Senators, and a confidante of Cleveland Mayors and area Congressmen, Gombos has been a prime Hungarian voice toward the American establishment. As editor of the Szabadság, America’s oldest and largest Hungarian language newspaper, as well as through his many cultural and civic involvements, he has been a consultant for Hungarian affairs, called upon by the Federal government, political candidates at all levels, as well as the local television and newspaper media.

The Szabadság, was for decades a daily newspaper. It has been a source of world news for the new immigrant, a community calendar for parishes and fraternal groups, and of course, a political forum at election time. Gombos through the Szabadság has played a decisive role in municipal, county and state elections for the last quarter of a century. In spite of the firm hand he wielded in electoral politics Zoli Gombis was also the understanding benefactor who could commiserate with the newly arrived “Zoltáns” who needed jobs and housing.

Andrew Dono. Andy has been the proverbial “Mayor of Buckeye Road.” For most of the Golden Era, he was the president of the United Hungarian Societies (UHS) the umbrella organization that coordinated the work of Greater Cleveland’s Hungarian parishes, clubs and fraternal associations.

Dono ran the UHS like a town council and was able to give it direction and purpose. His programs ranged from folk culture to solemn observances of Hungarian holidays. In politics he was tough. His organization worked the Buckeye Road wards with an efficiency that made him the kingmaker who could deliver the votes. The tough kingmaker had a very human side. The plight of the refugees fleeing the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was so moving to Andy, that he stopped his daily business to organize the fund-raising efforts to benefit them. He personally knocked on doors and sought out contributors to donate toward the food and the medical aid for the “56-ers.”

Many political appointees grow rigid and bureaucratic with time. Dono, however, served as a City Commissioner, and later, a Special Assistant to Mayor Carl Stokes, and through those terms he maintained a boyish humor that disarmed even his critics.

Jack P. Russell was born, Paul Ruschak. He built a career in politics that spanned 29 years in Cleveland city government. He was the longest running councilman of Ward 16, and served 11 years as President of City Council. In his early campaigns he displayed a rare quality of showmanship that blended the local Hungarian pride with the hard truths of ballot box victory. He could stage a dancehall entry to befit a European prince. His advance crew would arrange it with the house band that when the doors flew open, Jack’s entrance would be timed with a flourish of music. The band pumped the stirring strains of the “Rakoczy March” as the young Russell glided in amidst goose bumps and applause.

Russell was a newspaper reporter’s eternal source of news. He was brash, intimidating, but jovial and warm. His ten gallon hats, Havana cigars and black Fleetwood Cadillac gave him an aura and a style. For campaign literature he used the broadsides of four-story buildings. For the Buckeye boy with little higher education, he was called to Harvard University to lecture on urban politics. The ethnic from the wrong side of the tracks was selected by CBS as the subject of a nationally televised documentary on big city politics. Other Hungarian Councilmen to serve the area were Jack’s brother, William Russell, as well as Stephen Gobozy and Stephen Gaspar.

The Hungarian judges were widely acclaimed throughout their jurisdiction for their strong sense of human compassion coupled with their positive stands on law and order. In sheer number they were surpassed only by the Irish in their strong representation on the bench.

Louis Petrash, affectionately called “Mr. Magyar;” Joseph Stearns, the Kovachy brothers, Blanche and Robert Krupansky, all were to achieve distinction as exemplary judges and respected community leaders.

Pokorny family patriarch, Frank Sr., served as the district representative to the Ohio General Assembly. His son, Frank Jr. also served as State Representative and Cuyahoga County Commissioner. The Legislative district was also spoken for by State Representatives Joseph J. Horvath, Julius J. Petrash and Julius Krupansky. John Nagy was appointed Cleveland’s Commissioner of Recreation, an influential post he has held through seven mayors’ administrations.

Behind the elected officials were those community leaders who were not politicians themselves, but were responsible for keeping vital and cohesive a community that was the base for the political leaders. These included radio personalities such as the late Frank Szappanos as well as Ernie Hudak and Andy Dono, whose radio programs are still running strong into the 1980’s. Their programs have provided folk music, birthday announcements, community news and fresh entertainment. Alex and Betty Galgany typified the contributions of the strong support team behind the scenes in Little Hungary. A separate essay would be needed to list the many members that served on this team.

In all, each of these personalities shared a common characteristic of human warmth. Even in displaying anger, heavy handedness or assertiveness, their constituents knew that underneath the tough exterior was a neighbor with whom they have shared drinks and family yarns, and life went on on Buckeye Road.

The first 100 years of Hungarians in Cleveland was drawing to a close by 1970, and faster yet, the curtain was coming down on the Golden Era.

The grim reaper took his toll on a great many of the personalities. By the end of the 1970’s, the judges Petrash, Stearns, and Andrew Kovachy, as well as Jack P. Russell, Frank Szappanos and Alex Galgany were all to pass away.

The neighborhood base was fast eroding as the second generation Buckeye Roaders and their newly-arrived immigrant contemporaries followed the citywide trend of flight to the suburbs.

Those who left Buckeye Road failed to establish a successor neighborhood in the suburbs as the Slovenians had done in Euclid or as the Poles had done in Garfield Heights. Without a base, there was little hope for electing representatives.

The fabric of cultural identity and political cooperation was further torn by the fact that the sons and daughters of Little Hungary who moved out, rarely learned the Hungarian language and seldom patronized the Hungarian newspapers or radio programs.

Much of the Hungarian-American political stir in the 1970’s was caused by an entirely different group of Hungarians, the post-war arrivals. Coming to Cleveland after the Second World War and the Revolution of 1956, these immigrants largely settled on Cleveland’s west side and established their own organizations. Their political activity was limited to campaign year dinners for Republican officials such as Ralph J. Perk and George V. Voinovich. No one from the ranks of these Hungarians has been thus far elected to public office.

IN RETROSPECT

In its proper perspective, the Hungarian-American political experience in Cleveland, Ohio, is a story that deserves a special telling. It is a story that needs to be told to fill in a missing piece in the oft-told tale of the American mosaic.

Volumes of literature have been written and read on the brilliant rise of such earlier arrivals as the Irish, the Italians, the Jews and the Blacks. Their stories have been memorialized in textbooks, fiction, television and the movies. Little has been said yet about the invisible minority, the Eastern and Southern European ethnics who in their individual groups, are smaller, and began their rise later. They too had obstacles to overcome.

The Cleveland Hungarians triumphed over the immigrant syndrome. Drawn here in the 1870’s to walk streets paved with gold, they found themselves strangers to the language and customs. They began the American Dream in factories, mines and railroad yards. In two generations they were a leading political force in Cleveland.

Their success formula was nothing new, it was evident in the old Boston and New York wards decades before. It was the neighborhood. The neighborhood was held together by the language, the parishes, the newspapers and the radio programs. So long as the neighborhood held firm, the political base was potent.

When the neighborhood fell, the power eroded. In the early, 1970’s, with the death of many leaders and the exodus of the Hungarian population, the Buckeye Community disintegrated. When the base crumbled, it could no longer support political leadership.

Those who left Buckeye Road never recreated the old glories. Many children of the early settlers wanted to forget, and the Post-War Hungarians never knew where to begin. By 1980, politics became the past-time of a few.

Some will argue, that the political collapse was actually just the beginning of the American Dream. The young and middle aged Hungarians of the 1980’s are living in Greater Cleveland’s finest suburbs and are holding a disproportionately high number of gainful positions in the professions, the arts and business. In 1979, there were over a dozen Hungarian-American millionaires in the area.

Others will argue that the political demise is not in fact a collapse, but a lull during which the substance will survive and only the form will change. Just as the mainstream of American politics is moving rapidly from bossism and neighborhood machines, so too the new generation of Hungarian-American leaders in Cleveland is adapting to the new reorganization.

It is unlikely that a group that offered so much talent to Cleveland in the 1960’s will go unheard in the 1980’s. Carrying the accumulated lessons of a 1000-year history and a tradition of independence, thrift and family values, the contribution may serve the city well.

THE BUILDING OF A CHURCH BY AN IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY: THE CASE OF ST. ELIZABETH OF HUNGARY

By: Rev. Rick Orley

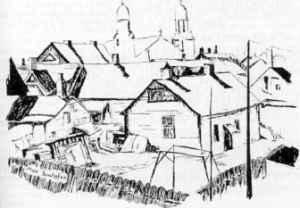

In the lower level of the Cleveland Museum of Art hangs a painting depicting the gray limestone towers of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary Church on Buckeye Road. Painted by Max Albin Bachofen, it shows the twin towers rising above rooftops, telephone wires and backyard fences. The title is “Sunshine in New Hungary”.

If the towers could speak, they would tell us not only of sunshine but also of great sacrifice. They would remind us that new will grow old for this turn of the century colony of Hungarians for whom this parish would be predominant even as the towers dominated the city-scape of the neighborhood. They would speak of Hungary as a loving memory and of the United States as a new found love.

The Parish was founded on December 11, 1892 by Rev. Charles Boehm, the first Hungarian Roman Catholic priest in the United States, only ten days after his arrival in Cleveland. Within months, this first Roman Catholic Magyar Church in North America had built a small brick church on Buckeye Road and East. 90th Street.

But it was the present massive stone structure, completed in 1922, that was the Hungarian colony’s way of saying “Yes” to America, “Yes” we will remain here and build this city, “Yes” we want our children and grandchildren to know our faith, our customs and traditions and to proudly practice them. It is true that a church is not just a building nor is faith built of limestone. But this church gave expression and articulation to immigrant fears and dreams, struggles and hopes, memories and visions.

The story begins on the 4th of May, 1907, when the “substitute pastor” of St. Elizabeth of Hungary Catholic Congregation, Rev. Julius Szepessy petitioned Bishop Horstmann through the Chancery to “build a suitable church for the enlarged member of the St. Elizabeth Congregation.” At that time, he was able to secure a loan for $150,000 at an interest rate of four percent.

Rev. Szepessy described the circumstances that prompted his request.

The success of spiritual work done by Rev. Father Charles Boehm stands higher than we are able to praise. All he has accomplished while exemplarily laboring in the last 14 years amongst his fellow countrymen, can partly be judged from the fact that he has cleared all the church debts… Now, my Dear and Right Rev. Bishop, allow me to state emphatically that the present Church-building is hardly half enough to locate all the practical Catholics belonging to our Congregation. There are hundreds of Hungarians who-without any exaggeration-have to turn home, even on common Sundays, because there is no room for all. The seating capacity of our present church is between 700-800. We need a church which would seat at least 1500 persons, because the number of contributing families is close to 700.

The petition was taken under consideration by the diocese and subsequently refused for the moment, described as, “the proposed debt is too large and unnecessary.”

Discussions and negotiations followed between people, pastor and bishop. A letter to the bishop dated June 22nd, 1909, and signed by six councilmen of St. Elizabeth Church gives us an example of their sincerity and their realism.

… we all want to belong to the St. Elizabeth Congregation and it is our comman goal to serve our God and Church by serving our Congregation.

We take the liberty of submitting this petition by mail as we are all workingmen and could not very well afford to miss a day in our work. We are, however, ready to appear before Your Rt. Reverendship on any day and at any hour, to be set by you …

Through all this the Hungarian colony grew. And the parish grew. It seems that the spiritual demands of the people became overpowering for Rev. Szepessy on what one would imagine was a cold and dreary January 13, 1910.

…For three years I have been the priest, advocate, I had to attend to all the different matters as come up in a Congregation, – I have been the treasurer and the servant of the Congregation and as such was, so to say, a slave of all these accumulated duties. The immense volume of work has ruined me, and having been compelled to spend most of my time within four walls in writing, the conducting of the accounts and with the great cares of responsibility, not only my eyesight was greatly impaired but I feel almost broken in soul and body…

He continued in describing his efforts to bring out additional priests from Hungary. Forty-four priests applied to the Magyar Minister for Religious and Educational Matters, Count Albert Apponyi, to come to serve the Hungarians in the United States. None came. The pastor continues:

Rt. Reverend Bishop; There are 800 children in our school, under the guidance of eleven Sisters. I have distributed 3166 membership-booklets among married and single persons not only for the purpose of supervising whether they abide by the laws of our Church but also for giving assurance to everybody that the 25 or 50 cents, paid in monthly are well taken care for … I dare say that the St. Elizabeth Congregation embraces about tenthousand (sic) souls. These good people bring their pennies, earned by hard work, to the parish-house or hand them to the collectors monthly … I ought to spend a great deal of time in our school and be the teacher, instructor of such children as do not speak yet English and who remain without almost any religious instruction if I cannot give it. And the sad fact remains that I scarcely can do it. Most of the time I am forced by the immense work to be done for the parish to be a clerk instead of a priest. I must be on my heels, from the morning until midnight, every day, I get only 5-6 hours of rest for the night and even the nights must be given, only too often, to the visiting of the sick because of the want of tact of many people who do not think until the evening of notifying the priest … I also most respectively beg for the granting of a leave of absence of two days so I could partly recover from the effects of the continuous strenuous work. I feel that by doing so, your Rt. Reverendship will save my life …

This particular January letter continues for four pages describing to the Bishop Rev. Szepessy’s physical health, his frustrations, problems with Hungary, present parish status and that final and humble request for a two day vacation.

A letter of response came from the Bishop’s secretary dated January 17, 1910 and it agrees with the pastor that some of the clerical-office work could be placed in the hands of a layperson. The two-day vacation was granted, “willingly,” and the bishop requested a copy of the weekly parish publication.

The councilmen of St. Elizabeth Church continued the argument as they were unwilling to accept “No” for an answer from the bishop. On February 23, 1912, they wrote a five-page letter to their bishop describing in detail their request for a, “new, grand church,” and their accompanying reasons. It is in a sense a 1912 painting of the Hungarian colony and their situation and lifestyles. One might remember that the four men who signed this letter were immigrants. All correspondence with the bishop was in the English language, not their mother tongue. That alone was no small feat. They begin by,” … presenting our humble request” …

… Our people is poor but honest, zealous in their faith, ready to make sacrifices for it, and always striving to comply with the divine and human laws … Our ethical progress is best shown by the statistics of our Congregation, our material progress is shown by the cash money deposited in the banks. Our numerical strength is amazing indeed. We have 835 children in our school. We are forced to congest them in eleven school rooms in order to take care of them … Our is not much more than a chapel. It is not high enough if is unhealthy, it cannot accommodate all our people even with several Masses, and it anything but fireproof. We have to dread the possibilities and dangers of a fire each Sunday. We had to install sprinklers in the vestry for at least partial protection in case of an accident. It is to be feared that the slightest alarm could cause the loss of life of hundreds of people as not a single foot of space remains unoccupied by worshipers … The balancing of our books for the year 1911 showed cash money of $40,646.59, and property worth at least $120,000 … The further steady material progress of our Church is assured by the sixhundred (sic) permanently settled, good, faithful, reliable families who possess property in our City and will spend the remainder of their lives here, with their large families. They can be relied upon as they have repeatedly shown that they consider their Church and School their dearest treasures and will never, under any circumstances abandon them … Having already over forty thousand dollars to our disposal we would need another fortythousand (sic) dollars and if your Rt. Reverendship would graciously grant that we should get a loan of $40,000 – at a reasonable rate of interest the affairs of our Congregation would be in the best of shape for many years to come … We can absolutely guarantee that this loan would be paid in five years … We beg to remain, kissing you consecrated hand, your most humble servants in Christ, …

The archives of the Diocese of Cleveland and other records are fairly sketchy. The next significant document is dated March 27th, 1917 – a letter from Rev. Szepessy to the Bishop of Cleveland. Ten years after the initial request, the petition remains for a, “permanent new Church edifice.” The parish was about to celebrate their silver anniversary, twenty-five years of parish life. There seems to be more optimism, more spirit, more hope in this letter and, a better financial basis on which to build a church. The old brick church was condemned by the city of Cleveland on May 15, 1916 and that fact alone would begin to influence the diocese. Fr. Szepessy presents his case eloquently, as always:

… The Lord helped us and we possess at present $55,000 – which amount will considerably increase by the time we start building the new Church. We most respectfully implore you, therefore, Rt. Rev. Bishop, to grant now, gracious permission to this good, honest people, imbued with true enthusiasm, and doing their duty at all times with filial obedience, for the erection of a new Church … Our old Church was built 25 years ago … The roof is in decay. It imperils the safety of the parishioners. It is inhabited by birds only. Our good, poor people is subject to the jeers of their fellow workers of other nationalities in the shops, and in their resentment over the insults, and overcome by a feeling of hopelessness, they entertain … suspicions as to the safety of the assets of their parish … Rt. Rev. Bishop! I dare say that the beginning of erecting a new Church is more of a necessity than bread to the starving ones … The new Church is planned to seat 1000 to 1100 people. It is to cost between 100 and 120 thousand dollars … In conclusion, I once more beg Your Rt. Reverendship, to lend your ear to the prayers, and longings of this poor struggling people. Without your grace, we would not even be able to provide for a more careful and comfortable education for our children, while our good people might begin to feel that they were left orphans …

The next few years again leave us with few records. It is not surprising. The country called up the “Doughboys,” sang, “Over There,” and faced its first world war. The Hungarian colony on Buckeye Road was no stranger to socialism, bolshevism or communism. (But that’s another story.) It was also obvious that the immigrant population was growing at a rapid rate. That meant that the Catholic population was also increasing. Witness Rev. Szepessy’s claim to hearing “700 even 800 confessor calls” every Saturday. The “new Church decision” was delayed since St. Elizabeth Church seems to have been ready to give birth to a daughter parish, the present St. Margaret of Hungary Church on East 116th Street, south of Buckeye Road. It was a decision between limestone walls and the spiritual care of people. A split, a division at this time was nearly disastrous and as Hungarians are wont to do, many discussions and loud protestations could be heard.

But through it all and above the sounds of war, the arguments of politics, the whispers of confessions, the murmurs of new birth, or the disagreements of elders, the most memorable sound from roughly 1917 to 1922 on Buckeye Road was, to quote a dear friend, “The ring of hammers and the song of saws,” Almost unceasingly! One needs only a windshield survey to assess that fantastic and classical 1920’s shopping strip of the neighborhood to recognize the names and dates that stand as witnesses to the “Golden Age of Buckeye Road.”

The conflicts were resolved in a compromise. The Bishop of Cleveland finally said, “Yes!” to the Hungarian colony. It was not until 1928 that the new church and school building of St. Margaret of Hungary was built. But it was on April 4, 1919 that a formal and final request was made of the bishop to build the present St. Elizabeth Roman Catholic Magyar Church and the petition was duly signed by the pastor and four councilmen, allowing expenditure of $100,000 for a “new church and new residence.”

The building of the new Church finally began. In a memorandum of contracts dated 1920, it is interesting to note the costs of furnishing the church. The steel doors and coal chute cost $390. The flooring was priced at just over six thousand dollars. The six huge chandeliers (about five feet by five feet in size, supported by cherubs and holding more than 80 light bulbs) were changed from bronze to bronze painted composition material at the price of $1,998.

One would have hoped that the building process would have gone smoothly. Unfortunately, the formal petition of April 4th, 1919 was just a formality. A letter of April 24th, 1919 indicates that the major portion of the structure was already built. The problems begin here. The Laws Construction Company is in difficulty and the court of appeals is Bishop John P. Farrely.

… We understand that a committee of said Church (St. Elizabeth) has called on you with reference to making a loan and were refused by you. No doubt you do not understand the situation on this particular building or otherwise we hardly believe you would have refused.

… We have this building about ready for roof and slaters are working on same. The first tower is nearly finished and will be in good shape to have both towers and all the roof on inside of one month.

… We have about $57,000 still due us on our contract and we think about $15,000 will finish our work, therefore you can see that we have about $40,000 of our own money standing out on this Church and it will be impossible for us to continue work on said building unless payments are promptly made.

We regret very much if we are compelled to close down as it would cost us a great deal and extra labor as well as extra cost and expense to said Church, inasmuch as we would have to clear all of the streets, tear down sheds, and offices and take down derricks and engines. Furthermore, it will leave this building in a very dangerous condition in case of storms, etc.

Four days later, Rev. Szepessy responded assuring the bishop in a three-page letter letter that the people could stand by their debts and he asked for permission for a new loan.

Again, the records are less than complete. In a letter from the bishop on September 3, 1919, permission is granted to St. Elizabeth Church to secure a loan to cover their debts and insure the building of the church. Only from a document of March 29th, 1920, do we understand the collateral and the sacrifice involved. Members of St. Elizabeth Congregation, immigrants who owned houses and businesses, negotiated second mortgages and personally loaned $64,000 in 1919 to their church, “for the continuation of the construction of our new Church edifice.” If Cleveland were Hollywood, it would not be the “Bells of St. Mary’s” but “The Miracle of St. Elizabeth’s.”

The Church was finally completed. It stands proudly today as a witness of love from the Hungarian colony; two towers of faith watching over the neighborhood; and a symbol of hope for all who will believe.

HUNGARIAN CULTURAL CONTRIBUTIONS

By: Lél F. Somogyi

Hungarians have made significant contributions to the cultural mosaic of the world and have been a moving force behind advances in the arts and sciences. Through innovations in lifestyles, they have contributed to the growth and advancement of Western civilization and culture. Through the arts they have enriched the literature, art, sculpture, music, law, medicine, and political direction of mankind. In the sciences, they have helped propel themselves and all of us into the Industrial Age and the Computer Age.

The exceptional contributions of the Hungarians can be largely attributed to the environment in which they lived, in a multicultural society that encourages innovation and scholarly study. The following sections only briefly describe the immense cultural evolution that took place in Hungary and its results.

Art and Architecture

The oldest example of painting can be found in the Church of Feldebro as a fresco sequence that dates from the mid-eleventh century. Another series of wall paintings dating from about 1200 and others from the thirteenth century show the Roman style. A fresco of the coronation of Charles Robert that hangs in the Cathedral of Szepeshely was done in the Gothic style. Other frescoes painted by the master artist John Aquila in the fourteenth century are also good examples of Gothic style. Many paintings remain preserved in Transylvania and Trans-Danubia.

The oldest illustrations drawn for a book appeared in the early part of the thirteenth century in the form of five ink drawings. In the “Illustrated Chronicle,” published in 1379, 142 colored miniatures by the Hungarian master Miklós have provided an invaluable aid in the study of dress and apparel of that period.

Examples of sculptural excellence can be observed in the column art of buildings as early as the eleventh century. Refreshingly youthful relief sculptures carved in the latter half of the twelfth century can be found in the Cathedral of Pécs. Statues and bas-relief works in the Church of Ják stand out as thirteenth century examples of Gothic style sculpture. Sculptures in the fourteenth century, the relief sculpture of Kassa’s St. Michael Church, group sculptures, memorials and cemetery statues all reveal a solid development in style and artistry.

Sculptors, such as the brothers Martin and George of Kolozsvár, created their pieces in bronze in the late fourteenth century. Unfortunately, in the course of time the only statue they created that was not destroyed was the statue of St. George on Horseback, which was finished in 1373 and remains preserved in Prague. Even by itself, it attests to the high level of expertise possessed by the artisans in this early period.

The Cathedral of Pécs was the first Roman style structure in Hungary. It was built between 1038 and 1041. By the end of the thirteenth century, the Roman architectural style began to give way to the Gothic. The transition is visible in the remains of the Church of Zsámbék, where the outside of the church remained in the Roman style, the inside plan was Gothic.

The Royal Palace of Esztergom was unique among the buildings built during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Many of the architectural innovations of the palace were unmatched elsewhere in Europe.

The earliest example of Gothic architecture can be seen in the Abbey of Topuszkó, begun in 1211. The Church of St. Michael in Kolozsvár and the parish of Szászsebes show Gothic characteristics that predominated in that period. Fortresses in Diósgyor, Visegrád, and Buda and city houses in Buda, Pécs, and Sopron that remain intact today also show the Gothic influence.

During the Renaissance the art of painting flourished in its various forms throughout the nation. Many painters are remembered from this period, including John Spillenberg (1628-1679), James Bogdány (1660-1724), John Kupeczky (1667-1757) and Ádám Mányoky (1673-1757), who achieved international fame.

Significant advances were also made in fresco, altar, portrait, crest and ceiling paintings, inspired by the new creative ideas and accomplishments of others.

In architecture, the prevailing Renaissance styles were used. The baroque style emerged strongly in the 1630s, the first example of it seen in the church of Jesuits at Naqyszombat.

In modern times, the painters Károly Markó, Sándor Kozma, Henrik Weber and the exceptionally talented Miklós Barabás were all recognized outside of Hungary before they achieved acclaim in Hungary. Károly Kisfaludy, Károly Brocky, József Boros and Count Mihály Zichy, the painter for the Russian czar’s court, were the first in a class of national romanticist painters who were active in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Viktor Madarász, Bertalan Székely, Károly Lotz, Gyula Benczur, Sándor Liezen-Mayer and Sándor Wagner are good examples of painters dealing with historical subjects. The work of Mihály Munkácsy (1844-1900) and Pal Szinyei-Merse (1845-1920) are categorized among those of the best painters in the world.

In sculpture, István Ferenczy (1792-1856) was a follower of the classic style, while Miklós Izsó represented the romantic style. Particularly talented sculptors included János Fadrusz (1858-1903), whose white marble equestrian statue of Mária Theresia was destroyed in Pozsony but whose equestrian statue of King Mátyás still stands in Kolozsvár; Lajos Strobl; György Zala and most recently Zsigmond Kisfaludy Strobl.

The best known architects of Hungary included Joseph Danko; Frederick Fessl; Frederick Schulek, who designed the Fishermen’s Bastion; Emery Steindl, who designed the Parliament; and Nicholaus Ybl, who designed the Opera House and the Royal Castle. Representatives of the Hungarian style included Ignatius Alpár, Edmund Lechner and Charles Koós.

Music

During the Middle Ages minstrels passed on stories of ancient and heroic deeds through song. Usually performing both in the royal court and on the popular entertainment circuit, the minstrels spread news and information about the past and the present. Music was used only as an accompaniment to the song of the minstrel, and did not evolve into a separate art form until later. Common instruments used at the time included the horn, violin, drum, and hand organ.

Historical melodies from the past determined the direction of Hungarian musical expression in the sixteenth century. Composers such as Sebastian Tinódi Lantos and Michael Sztárai stand out in this early group. Many of these composers performed their own works on the lute. Valentine Bakfark, active during the middle of the sixteenth century, was the first Hungarian lutist composer and performer known throughout Europe.

In the second half of the sixteenth century, the gypsies wandered into Hungary accompanying the Turks. They brought a distinctive Arabic-Turkish musical heritage to Hungary. The gypsies adopted the Hungarian musical forms, but added their own musical flair to them in performance.

Dancing was still considered essentially sinful, but was condoned in traditional celebrations. The first description of the “hajdu”-dance occurred in 1558. It was from this dance that the “toborzó,” the classic Hungarian recruiting dance, developed after 1688. The “kanász” dance, the herdsmen dance, was first performed by Valentine Balassi at the king’s court in 1572. The extremely dignified dance, the “palotás,” was to be performed in the palace, and was first described in the literature by Abbe Reverend, charge d’affaires of the French king at the court of the Transylvanian prince about 1690.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the creative arts grew and theater expanded. Dance, song and music all quickly assumed Western characteristics, while still retaining and perserving Hungarian national traditions. In 1835 a new national dance, the folk dance called “chárdás,” appeared in the playhouses and the dance halls. All types of dances were studied and many new dances, based on traditional Hungarian dances, were developed and performed.

Music emerged as the creative art that preserved and expanded national traditions the most beautifully. The renowned Ferenc Liszt (1811-1886) brought new form to Hungarian music through his piano performances and compositions. Ferenc Erkel composed the musical score for the Hungarian anthem, and Mihály Mosonyi established the Hungarian national operas. Ferenc Lehár, Imre Kálmán and Jeno Huszka wrote a whole sequence of operettas. Erno Dohnányi, as a follower of the romantic period, sought out the relationships in folk tunes. He established himself as the original surveyor of a new Hungarian classical movement, following in the footsteps of Liszt, Erkel and Mosonyi. The music of Béla Bartók (1881-1967) was saturated in folk tunes, yet was presented in a new and sophisticated modern way. Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) emerged as a fitting competitor of Béla Bartók. Together these two giants won Hungary a new musical reputation which is still upheld today.

Literature

The culture of the Hungarians in ancient times was Eastern in form, as reflected even in their writing. In “rovás,” the letters were carved into wooden arrowshafts or canes and sticks from right to left. Only centuries after its development was it used in wall carvings. It is an undisputable fact, however, that even before occupying the Carpathian Basin the Hungarians had a well developed written language.

Latin and Hungarian were the languages used during the Middle Ages. They were used in a dual manner as were the ancient Turkish and Hungarian languages centuries earlier. The official language of literature and government was Latin, as in other parts of Europe. Records were kept in Latin, and church hymns and hymnals were composed in Latin. A “gesta,” an ancient writing from the eleventh century was the oldest known record, but was lost sometime in the Middle Ages. Another “Gesta Hungarorum” remains as the oldest “gesta” today. It was written by an anonymous author in the late twelfth century, who is known today to have been Péter Pósa, bishop of Bosnia. Around 1280 Magister Simeon Kézai wrote another historical work entitled “Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum.” Of all the chronicles, the “Illustrated Chronicles” published in 1358 by Mark Kálti remains as the most famous and important work.

Hungarian words were quoted in Latin sources as early as 1055. Prose from around 1200 and a poem from 1300 remain as the earliest examples of both styles. The oldest Hungarian hand-written codex dates from 1370.

The first Hungarian printing presses went into operation in 1471 under the capable direction of Ladislas Karai. The first printed book in Hungary was prepared by Andrew Hess in 1473. Franciscans around the world used the book of homilies by the Hungarian Franciscan Pelbárt Temesvári.

The development of Hungarian language and literature paralleled the spread of the Renaissance. Latin gave way and Hungarian became the language of literature.

The renewers of the faith were also writers and publishers of considerable talent. John Sylvester Erdosi translated the New Testament into Hungarian in 1541. By 1590 the Calvinist translation of the whole Bible was completed by Casper Károli and by 1626 Jesuit George Káldi finished the Catholic Bible translation.

During this period poets appeared who were not priests or ministers. Sebastian Tinódi Lantos; Valentine Balassi, the first Hungarian lyricist; Count Nicolas Zrinyi, the author of the first Hungarian epic; and Stephen Gyöngyösi, all made definitive contributions to poetry. Zrinyi’s epos speaks of the historic mission of the Hungarian nation, paving the way for later poetic tributes to the nation.

During the Reformation and Counter-Reformation period, the use of the Hungarian language became widespread in literature. Exemplary works of this period include the “kuruc”-poetry, Kelemen Mikes’ “Letters from Turkey,” the poems and prose of the Jesuit Ferenc Faludi, the historical works of Mihály Cserei, and the history of literature works of Peter Bod.

Hungarian writers began to emulate the example of Latin, German and French literature. Others followed typically Hungarian traditions. At this same time, a general language reform movement was initiated nationwide.

Some of the best known poets that emerged at this time included Mihály Csokonai Vitéz; Sándor Kisfaludy; Dániel Berzsenyi, known as the Hungarian Horace; Ferenc Kölcsey, remembered as the author of the Hungarian national anthem; Károly Kisfaludy, who continued the work of the organization of writers started by Ferenc Kazinczy; and József Katona, remembered as the best Hungarian tragedian.

To preserve and strengthen the Hungarian language and literature, an Academy of Science was founded in 1830. With the successful emergence of Mihály Vörösmarty, the romantic movement in poetry spread rapidly, lending great impetus to the development of the language and literature of Hungary. Gergely Czuczor, József Bajza, Baron József Eötvös and János Garay were the most famous poets of this romantic category. The popular poetry of the talented and world famous Sándor Petofi introduced an original, completely new, but classic tendency into Hungarian poetry. He had many imitators and even more followers who used his work as a model. Of the latter, János Vajda, Gyula Reviczky, Sándor Endrodi and Kálmán Tóth are especially noteworthy. János Arany is credited with creating the most peculiarly Hungarian form of poetry. Mihály Tompa, Pál Gyulai, József Lévay, Károly Szász, Kálmán Thaly and László Arany, who was the son of János Arany, are the most memorable poets among his contemporaries.

With the emergence of regular theatrical performances came the growth of dramatics. By 1860 Imre Madách had written his eternal human drama, “The Tragedy of Man.” Among the novelists Baron Miklós Jósika, Baron József Eötvös, and Baron Zsigmond Kemény attained distinction. The prolific Mór Jókai, the great story-teller, reaped world-wide success and acclaim that has remained unparalleled since by any other Hungarian.

The symbolic poetry of the especially talented Endre Ady established a new direction for poetic expression in the early part of the twentieth century. His contemporaries included Emil Ábrányi, József Kiss, Miklós Bárd, Andor Kozma, Mihály Babits, Dezso Kosztolányi, Gyula Juhász, Mihály Szabolcska and Árpád Tóth. Jókai’s position in prose was taken over by the satiric Kálmán Mikszáth, the popular Géza Gárdonyi and the foremost prose writer of the period, the elegant, conservative Ferenc Herczeg.

Hungary continued to turn out more and more excellent writers. Between the two world wars, as a consequence of the Trianon Treaty which partitioned the thousand year territory of Hungary into four parts, Hungarian literature also developed along the lines of four different and distinct categories. In Hungary, Ferenc Herczeg, Zsigmond Móricz, Dezso Szabó, Lajos Zilahy, Miklós Surányi, Zoltán Szitnyai, János Kodolányi, István Eszterhás created prose works. Lajos Áprily, Lorinc Szabó, Sándor Sík, Lajos Harsányi, Attila József, István Sinka, Gyula Illyés, Sándor Weöres and many others devoted their efforts to poetry, promoting the Hungarian language and literature. In addition to the two great playwrights, Ferenc Herczeg and world renowned Ferenc Molnár, many more talents appeared including Janos Kodolanyi and Marton Kerecsendi Kiss.

In Transylvania, Áron Tamási; József Nyíro; Károly Koós; Albert Wass, who is now in America; and the great poet Sándor Reményik are worth special attention.

In the north, in Czechoslovakia, Lászlo Mécs, the Catholic priest-poet, became one of the greatest Hungarian poets. In the south, in Yugoslavia, the Hungarian authors gathered in a group under the leadership of Károly Szirmai.

Science

With the coming of the Industrial Age, Hungary joined in the revolution in engineering and the sciences which is still in progress today. Hungary produced gifted men and women who helped lay the groundwork for the massive technological changes that have taken place all around us. Only the most noteworthy can be singled out from the hundreds who have taken an active and usually leading role in the advancement of the sciences.

These outstanding Hungarian minds included Johann Andreas Segner, a mathematician and scientist who is chiefly remembered for his invention of the turbine; Joseph Carl Hell, pioneer in mining mechanization and pumps; Maximilian Hell, mathematician and astronomer; Wolfgang, Kempelen, scientist and inventor of the mechanical chess player; Ányos Jedlik, inventor of the electrostatic impulse-generator; János Bolyai, mathematician who constructed non-Euclidian geometry; Tivadar Puskás, the inventor of the telephonic newspaper and the first operational broadcasting organization; Lóránd Eötvös, inventor of the torsion balance; David Schwarz, inventor of the dirigible; and Donat Bánki and János Csonka, inventors of the modern carburetor.

Others included Károly Zipernowsky, Miksa Déri and Ottó T. Bláthy, inventors of the transformer; Kálmán Kandó, mechanical engineer and pioneer of railway electrification; Theodore Kármán, aerodynamics expert and the father of supersonic aeronautics; George Hevesy, Nobel Prize laureate in chemistry; Oszkár Asbóth, inventor of the helicopter; Imre Bródy, inventor of the krypton lamp; Dénes Mihály, pioneer of television in the 1920s; Kálmán Tihanyi, pioneer of television in the 1930s; Leo Szilárd, physicist and initiator of large-scale nuclear research in the U.S.; Georg Békésy, Nobel Prize laureate in physics and biophysics; Albert Szent Gyorgyi, Nobel Prize laureate in chemistry; and John Neumann, mathematician, developer of game theory, and inventor of the modern digital computer.