Section I: History of Hungary

The Árpád Kings

The Hungarians or Magyars settled in the Carpathian Basin (the area which includes present day Hungary) in 896, more than 1,000 years ago. In ancient times, the homeland of the Magyar tribes, an area known as Bashkiria, was on the western border of southern Siberia, along the Volga. In this region, the ancient tribes came into contact with numerous tribes living on the steppes north of the Black Sea and later with Turkish tribes who made frequent incursions into this area through the passes of the Urals. Evidence of close contacts with these Turkish peoples, through a large number of loan words found in the Hungarian language, have been traced to this period.

Bashkiria, or Magna Hungaria, came under the domination of the Khazar Khaganate, an alliance of Turkic tribes from central Asia. Around 830 A.D., the Magyar tribes left Bashkiria and migrated west to a plains area north of the Black Sea-between the lower Danube to the Don. This area was called Etelkoz, or country between rivers. Although wedged between Khazar and Eastern Slav tribes, the Hungarians retained independence with regards to their political and economic affairs during this period.

Etelkoz afforded little protection from warring tribes, however, and in 896 the Hungarians migrated further west in search of a new homeland. In that year they occupied the Carpathian Basin, conquering the areas populated by Avars and Slav tribes. By the year 900, they had taken possession of Transdubia, the area west of the Danube as well. According to estimates, the population of the Magyar tribes at the time of the conquest was 500,000.

The Magyars of the ninth century were a nomadic pastoral people, advanced in the techniques of animal husbandry, especially horse breeding. They were familiar with primordial forms of agriculture. They made earthenware and could weave and spin cloth. Magyar society consisted of a highly organized system of family clans belonging to seven tribes, namely: Nyék, Magyar, Kürtgyarmat, Tarján, Jeno, Kér and Keszi. The chiefs of these seven tribes symbolically entered into a blood brotherhood and through sworn allegiance became one nation. They chose one leader-Árpád, son of Álmos-to be their supreme leader during the migration.

After occupying their homeland, Magyar warriors set out on military campaigns into western Europe. The purpose of these campaigns was twofold: to determine the number and strength of nations to the west and to ward off any incursions into the Carpathian Basin by a show of might. Despite other tribes (i.e., Normans, Arabs) also raiding Europe at the time, the Magyars were overwhelmingly successful. They travelled extensively into the present day territories of Germany, France, Italy and even Spain. Their military success was largely due to light cavalry tactics, great mobility, routine and discipline. The incursions continued until the Magyars were decisively defeated by the Germans at Merseburg in 933 and Augsburg in 955.

The descendents of Arpad ruled the Magyars for over 400 years afterwards. They systematically transformed a wandering pagan people into a westernized Christian nation. Prince Géza, great grandson of Árpád, ascended to the throne in 972. Géza brought in Christian missionaries from Germany and was one of the first to be baptized. In converting to Christianity and introducing the new faith to his people, Géza and his son, Stephen, determined the future of Hungary by linking it with Rome and the west in lieu of Byzantium and the east.

King St. Stephen (997-1038, Hungary’s first Christian king, consolidated the work initiated by his father. He quelled all resistance among the various tribes refusing to accept Christianity. Stephen established two archdiocese and eight diocese and invited religious orders to take up missionary work among the Hungarians. In recognition, Pope Sylvester II sent a Holy Crown and bestowed the title, “King by the Grace of God,” upon Stephen. This title was conferred by the Pope only to the ruler of an independent country. Stephen was crowned in 1000 A.D. with the Holy Crown, traditionally a symbol of the sovereign state of Hungary. Since that time, all the Hungarian kings have been crowned with this ancient apostolic coronet until the early part of the 20th century.

During his reign of four decades, St. Stephen established the foundations of the Hungarian state. Villages and towns were founded in attempts to settle the tribes and develop an agrarian society. The country was divided into counties called comitatus. Stephen established a lasting code of law which included many innovations such as private land ownership; until then tribes or clans owned land collectively. He secured Hungary’s position by building sound relations with many other organized nations in western and central Europe.

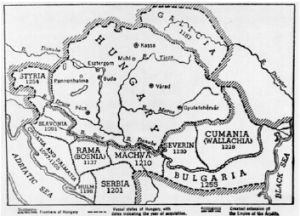

The fate of Hungary during the reign of the Arpad kings largely depended upon the strengths and/or weaknesses of the respective rulers. The highlights of this period include the reign of King St. László (1077-1095), whose legends of valor and bravery were renown throughout Europe. Croatia was incorporated into the Kingdom of Hungary in 1091, along with Slavonia and Dalmatia. A separate viceroy or bán was appointed to oversee the government of each of these territories, their duties included: to appoint their own báns and bishops, to confirm the royal privileges, to act as supreme judge, to mint their own coins, to direct the finances of the realm and to convoke the diet. These territories enjoyed home rule, based on each districts historical tradition and constituted an independent part of Hungary for over 800 years, until after the First World War.

An enlightened lawmaker, King Coloman the Learned (1095-1116), set forth enactments which were far in advance of his time. Coloman brought about reforms in legal procedure, making the testimony of witnesses the basis of all evidence and lessened the rigors of the written law. Coloman banned the trial of witches, declaring that no mention of them be made as witches do not exist. This ruling was unprecedented, it was made at a time when the savage practice of witch burning was just gaining momentum in Europe.

The First Royal Chancellory, which documented every royal decree, judgment, ruling and transaction at court was established during the reign of King Bela III (1172-1196). One of the notaries of the Royal Chancellory was a scholar known by the Latin appellation Anonymus (unknown). His work, the Gesta Hungarorum, describes the origin, migration and settlement of the Magyar tribes. For the first time, the Latin alphabet was used for Hungarian words in this original work.

The Hungarian court was considerably influenced by French culture during this period. Sculptors from France assisted in the building of the Royal Castle at Esztergom. Hundreds of Hungarian students studied at the University of Paris. Cistercian monks were brought to Hungary by the king. It was a time of prosperity marked by an evolution in farming methods and industrial and commercial growth.

The immediate successors to Bela were inept rulers, their reign brought about a deterioration of centralized authority. In 1222, in response to the increasing power of the oligarchic or magnate class, King Andrew II (1205-1235) issued the Golden Bull, which clearly defined the duties of the monarch and the nobility. The historical document defended the liberties of free men and confirmed the privileges of the nobility. Moreover, the Bull guaranteed the freedom of the descendants of the original Magyar settlers, who were thus protected from becoming the serfs of the magnate class. The rights of the lesser nobles were affirmed. The ranks of the nobility expanded in subsequent periods and included members of Hungary’s ethnic minorities, i.e., Slovaks, Rumanians as well. The Golden Bull was historically significant because it served as the foundation of the Hungarian Constitution. Its content was strikingly similar to the English Magna Carta (1215), which preceded its Hungarian counterpart by only seven years.

The invasion of the Tartars or Mongols in 1241 presented a serious threat to Hungary’s existence and survival as a nation. As early as 1223, the combined forces of the Russian and Cuman armies suffered a terrible defeat by the Tartars. King Bela IV (1235-1270) sensed the impending disaster and made every attempt to prepare the country for the conflict, however, several factors hindered his work, including the fact that the west, not being able to comprehend the might of the Tartars, hesitated in assisting Hungary. The Tartars easily crushed all resistance at the border and met the Hungarian armies at the plains of Mohi in northeast Hungary in 1241. The Magyars, outnumbered and outmaneuvered, suffered a terrible defeat; the entire army was practically annihilated. King Bela narrowly escaped death.

Devastation of the country ensued. The invaders pillaged the countryside, slaughtering the inhabitants and burning crops, villages and towns. The population was decimated; thousands were taken into slavery. Those who survived did so only by taking refuge in the forests and marshes. Hungary lost one-half of her total population. The most severely affected area was the Alfold or plains region of central and eastern Hungary. During the winter of 1241-42, the Tartars crossed the frozen Danube and moved into the western half of Hungary, the Dunántúl. Quite unexpectedly, Hungary was then freed of this great calamity by the death of the Great Khan Ogotai in Asia. Batu Khan, commander of the armies in the west, gathered his armies and returned to succeed the Great Khan.

King Bela initiated the work of rebuilding the devastated country. Magyars who survived the disaster returned from hiding. In some parts of Hungary, where the population was completely annihilated, non-Magyars were brought in for resettlement. Bela organized a new defense system, building a chain of fortresses along the border. New towns were built, encouraged by various incentives and freedoms granted in town charters. The army was reorganized, the light archers traditionally used were replaced by heavy cavalry.

By the time of his death in 1270, King Bela had successfully rebuilt the country, for this work he was dubbed “The Second Founder” of Hungary. Bela established sound relations with the Angevins of Naples and the King of Bavaria and secured Hungary’s position by marrying his children into these royal families. One of Bela’s daughters, Margaret, was canonized a saint for her charitable works and piety.

The last male heir of the Árpád Dynasty, King Andrew III, died in 1301. The lineage provided Hungary with notable lawmakers, administrators, soldiers and saints. During their 400 year reign, an independent Hungarian state was established and its position in central Europe was secured. The Árpáds laid the foundations, their work enabled Hungary to withstand and survive for centuries.