Section II: Hungarians in America

The Great Immigration (1870-1920)

A. One Million Hungarians

Between 1870 and 1920 an estimated 1,078,974 Hungarians immigrated to the United States.[1](This figure does not include the ethnic minorities who came as citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.) Those who made the arduous journey to the North American continent were lured by the prospects of economic opportunities. The United States, on the other hand, was in need of cheap labor to maintain and expand its industrial potential.

Around the turn of the century, the flow of immigrants to the United States shifted from western and northern Europe to central and southern Europe. The Industrial Revolution in England, France and Germany literally halted the flow of immigrants to the United States. Rapidly expanding industry, however, created an even greater demand for manpower; Italy, Austria, Hungary and Poland became new centers for the recruitment of workers. By 1910 over nine million immigrants had arrived in the United States from these regions in Europe. This mass migration has been attributed to the combined effects of “push” from the country of origin and “pull” exerted by the United States.

The “push” was primarily caused by poverty and overpopulation in the countryside. Hungary’s population was augmented by two million in the 1880s. This aggravated the situation of the agricultural laborers, to whom the increased numbers of workers meant lower wages and less work. Moreover, the problem of overpopulation exerted greater demands on the already limited amount of available farmland. A semi-feudal land ownership system determined that one-half of all arable land belonged to landowners with large estates (ranging from a few thousand acres to 50,000 and 150,000 acres) and medium-sized estates (from seventy to 700 acres).[2] The other half of the agricultural population consisted of small landholders, dwarf-landholding farmers and landless agricultural peasants. Small landholders owned from fifteen to seventy acres and were able to make a living from their own property. The dwarf-landholding farmers owned a house and maybe a few acres, but could barely subsist on their own land. This latter group, along with the landless agricultural workers were the ones who immigrated to America.

Working and living conditions were inhuman. Landless agricultural workers worked from sunup until sundown for usually less than twenty-five cents a day. Industry was barely developed in Hungary, and the poverty-stricken peasant could not find work in a nearby city or town. The over-abundance of laborers often resulted in maltreatment and abuse from overseers and landlords. Many of the peasant laborers had their fill of the back-breaking work and starvation pay. They gambled everything on steerage to America because they had little to lose and everything to gain.

Several factors contributed to the “pull” to the United States, such as: recruiting agents and letters and/or money sent by fellow countrymen already in America. Agents recruiting cheap labor for demanding American industry afforded the means by which the peasant could gain passage to America. Usually, because of conditions in the homeland, it didn’t take much convincing on the part of the agent. Some companies such as the New Brunswick, New Jersey-based Johnson & Johnson hired a staff of recruiting agents and contracted shipping lines to bring shiploads of immigrants from Fiume directly to New Brunswick. Fiume was the main point of embarkation for immigrants from Austria-Hungary destined for the United States. In retrospect, the agents were highly successful, nearly ten percent of Hungary’s population immigrated to America between 1870 and 1920.

The pull was further augmented by money and letters sent by fellow countrymen already in America; both provided testimony of the favorable working conditions and high pay in the United States. At the height of immigration, Hungarians in America sent home as much as one hundred to two hundred million kronen annually. According to estimates, the highest annual remittance was 125 billion kronen or the equivalent of $50,000,000.[3] Families which received significant amounts of money from America built new homes, bought land and paid off mortgages. Such concrete testimony of success in America promoted immigration in the entire surrounding district.

Letters, such as the following written to the village of Komárom, provided eyewitness accounts of life in America. The contents of such letters were made known to relatives, friends and eventually, the entire village. Letters relating the hardships, alienation and tragedies were usually

Here a man is paid for his labors, and I am certainly not sorry that I am here. I work from six in the morning until seven at night and get $10-$11 a week. Just now, it’s hot. When it gets cooler I’ll make more money, perhaps double, and then I’ll work only eleven hours. There are 10,000 workers in this shop and my wife is working here too. She makes $9.50 a week. At home I made that much money in a whole month and people thought my job was very good. Here I am sewing dresses on a machine. In America there is no difference between one man and another. If you’re a millionaire you are called a Mister just the same and your wife is Missis.[4]

The net result of all these factors combined was that entire villages were depopulated. The Hungarian government realized only too late the implications of such a loss of manpower to the nation’s economy.

The majority of Hungarians who immigrated to America at this time came with the intention of returning to Hungary, hopefully with enough money to purchase land. Emigration began in the following counties of northern Hungary: Abaúj-Torna, Sáros, Szepes and Zemplén. Migration began in districts where harsh economic realities, caused by such factors as crop failure, unemployment and widespread hunger put a great strain on the population.

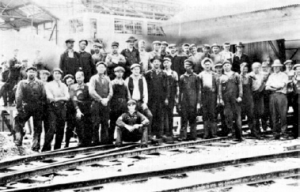

Initially, single men and men who left their families behind constituted a large percentage, over seventy-three percent of this emigration. During the years preceding World War I, however, the number of women emigrating equalled that of men. Three-fourths of these Hungarians were between the age of twenty and forty-nine. And over eighty-nine percent were literate. In America, they stayed in the industrial northeast, where they found immediate openings as unskilled laborers in steel mills, foundries and coal mines. At that time, industry paid fifteen cents an hour. Unskilled laborers worked ten to twelve hours a day, usually earning between $8 and $12 a week. The occupational breakdown of the Hungarians who immigrated was: 77.5 percent-agricultural workers and unskilled workers of all kinds; 8.6 percent-skilled workers; and 13.5 percent-miscellaneous occupations.[5]

States with particularly large concentrations of Hungarian immigrants were: New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Ohio and Illinois. Living in close proximity to fellow countrymen already in America was important. It provided the newcomer, thrust into a foreign environment, with a certain degree of security. Numerous examples attest to such “group migration.” From one district in northern Hungary, Bodrogköz, more than 7,000 immigrants settled in the state of Ohio. The Hungarian community of Homestead, Pennsylvania, was composed largely of immigrants from the county of Ung.

They lived in large overcrowded boardinghouses, where sometimes even the beds would be shared by men working on different shifts. The immigrant women who ran these boardinghouses never had a moment’s rest; the work involved was overwhelming. It was a privilege for an immigrant to have a bed in a boardinghouse run by a Hungarian woman and, above all, to receive Hungarian-style home-cooked meals. The boardinghouse manager cooked the meals, washed all the boarder’s clothes and cleaned the house. For this, each boarder paid around $3 per week.

More than half of those who arrived prior to 1914 managed to return. World War I and its outcome dramatically altered the lives of thousands of Hungarians in America, many of whom were living as aliens in the United States. As such, they were unprotected from discrimination and other forms of injustice directed against them because their homeland was on the “other side” during the war. Many simply accepted this situation and returned to Europe. Others returned because they wanted to rejoin their families and help assure their safety. The treaty which followed the war, the Treaty of Trianon, partitioned several sizeable sections of Hungary. Thousands decided to return to their villages in the midst of such political and economic upheavals.

Those who stayed realized that this decision was a permanent one. After 1920 increased numbers of Hungarians purchased homes and became citizens of the United States. Others abandoned the hope of returning after long years of working and saving, or simply adjusted to life in America and chose to stay. Still others never returned because they lost their lives in a coal mine cave-in or a steel mill explosion.

B. Labor Conditions

American industry exploited the masses of unskilled immigrant laborers. The newcomers were handicapped by language barriers and unfamiliar with labor conditions. The one dollar a day wage seemed unbelievable when compared to what they were earning in their native land. Because of the seemingly high wages, they were willing to work long, strenuous hours under hazardous conditions to save money. A Hungarian worker in a Pittsburgh steel mill noted: “Wherever the heat is most insupportable, the flames most scorching, the smoke and soot most choking, there we are certain to find compatriots bent and wasted with toil.”[6]

Safety standards for mines and steel mills were virtually non-existent around the turn of the century. Numerous mine cave-ins and steel mill explosions occurred, causing the death of countless immigrant workers. The enormous loss of life generated impetus for the enactment of safety legislation and improved industrial safety standards.

Szabadság, in its twentieth anniversary issue, printed in 1911, documented some of the Hungarian immigrant deaths attributed to steel mill and mining disasters in the United States:

| 1901 December 19 | Pittsburgh Steel Mill explosion 12 Hungarians dead |

| 1904 January 25 | Harwick Coal Mine disaster in Cheswick, Pa. 51 Hungarians; 180 total deaths |

| 1907 | Arnold City mining disaster 24 Hungarians dead |

| 1907 December | Monangah mining disaster 100± Hungarians; 362 total |

| 1911 August 8 | Youngstown Steel Mill explosion 14 Hungarians; 17 total 30 |

The Bluefield Mine fire in 1911 and the Johnstown Mine explosion in July 1902 were other mining disasters where the number of Hungarian immigrants killed was significant.

The families of the men who were maimed or killed in these industrial accidents became destitute. There were no state-sponsored programs of insurance to assist the widows and orphans of such casualties. The immigrants soon realized this and to provide some measure of protection, formed self-help and mutual benefit societies.

The grueling, unsafe working conditions had to be tolerated, there was little other alternative. The Hungarians were handicapped by language barriers, by a large number of other newcomers eager for employment opportunities, and by the fact that the next job may be just as bad if not worse. Putting their sorrow and yearning into music sometimes helped. The theme of the following folk song may be found in countless other Hungarian-American poems and short stories as well:

The coal powder absorbs our tears, Our laughter is drowned in smoke, We yearn to return to our little village Where every blade of grass understood Hungarian.[7]

Central and East European immigrants were frequently brought to the United States as strikebreakers. Large industrial firms, unwilling to cede to the strikers’ demands of fewer hours, increased wages and/or safer working conditions, simply brought a shipload of immigrants from Europe to fill the striking workers’ jobs. The agents recruiting such workers were usually instructed to choose immigrants of many different national origins, so that it would be difficult to organize the newcomers because of language barriers.

The newcomers were bewildered by the situation, and could not understand the reason for the hatred and violence directed against them by the strikers. For many Hungarians coming to the United States in the early 1900s, this was their first encounter with organized labor.

The first Hungarian-American labor organization, seeking to inform Hungarian immigrants about labor conditions and workers’ rights, was established in 1902. The movement separated in 1904, and two distinct groups were formed: the American Hungarian Socialist Federation and the American Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Federation. Both groups provided sick benefits and maintained newspapers. They were instrumental in encouraging Hungarian immigrants to join the American labor movement and to participate in the strikes organized by the movement.

It would be impossible to list all the strikes in which Hungarian immigrants were involved, however, the following were significant: the Homestead strike in July 1892, the Pullman strike in June 1894, the Rochester strike in July 1901, the coal strike in Pennsylvania in May 1902, the strike of 1908 in Perth Amboy, New Jersey and the 1910 steel strike in South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.[8] According to one author, of the 113 strikes which were organized between 1905 and 1910, Hungarians participated in seventy-seven.[9]

The demonstrations and strikes frequently ended in tragedy. In 1897, a labor protest was caused by a foreman’s imposition of a new work rule at Honey Brook Colliery near Hazleton, Pennsylvania. In quick succession, the ethnic communities in the entire region went off the job in support of the striking Honey Brook workers. At one meeting held near McAdoo, it was estimated that some 9,000 striking workers, “mostly Hungarians and Italians, gathered…to await the management’s response to their demands.”[10] Two days later, when the miners marched on the Lattimer Mines, the local sheriffs, leading a group of about seventy armed men, followed them and gave orders to shoot into the unarmed assembly, killing eighteen and leaving more than forty wounded. Most of the strikers were shot in the back. Among the dead: four were Hungarian immigrants, of the wounded, nine.[11] This tragedy became known as the “Lattimer Massacre.”

Over fifty-six churches, built by Hungarian communities in the mining and heavy industrial sections of Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia attest to the magnitude of the number of immigrants who worked there at one time. The records of these churches document through the years the staggering death rates which were so common in these regions of the United States. A Hungarian miners’ sick benefit society, named for the Hungarian millenium, was already established in 1896 (“Milleniumi Magyar Bányász Betegsegélyzo Egylet”). By 1911, fifteen chapters were organized, scattered throughout the mining towns of Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Virginia. Benefits paid over the first fifteen years of its existence totalled: $41,895.77.[12]

“A man is a man even if he is Hungarian”-unidentified journalist.[13] Resentment and discrimination were experienced by each new wave of immigrants and Hungarians proved to be no exception. Hungarian immigrants were handicapped from the start-they spoke a strange language and even if they learned English, the easily detectable accent was obvious. They were resented because they took the lowest paying jobs and lived on next to nothing, saving everything to return to their native land.

The phenomenal influx of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe triggered widespread fear and hatred of foreigners. The immigrants suffered grave injustices-in cases of civil disturbances, local police, judges and authorities: “…generally levied stiffer sentences against aliens than Americans, while newcomers victimized by native criminals often watched helplessly as their antagonist was let off with a mild reprimand.”[14] This was true especially in the hinterland or backwoods regions of the United States. In one incident which took place in the town of Jasonville, Indiana in 1909, anti-immigrant sentiments heightened to such an extent that the “native” residents took up arms and forced the Hungarian immigrant community to evacuate Jasonville, leaving most of their valuables, homes and properties behind.[15]

Individual examples of injustice were widespread. Peonage is defined as the practice of holding a person in partial slavery to work off a debt. Though illegal in the United States, peonage was widely practised. A Hungarian who tried to escape from a Georgian lumber camp was horsewhipped and tied to a buggy on the way back to the camp. Later when charges were brought against the owners of this particular camp, the Hungarian immigrant observed the “peculiar kind of justice enacted”:

…nothing was too strange as to find that the bosses who were indicted for holding us in peonage could go free on bail, while we, the laborers, who had been flogged and beaten and robbed, should be kept in jail because we had neither money nor friends.[16]

On several occasions unjustified newspaper campaigns were launched against Hungarians. Often the newspaper writers and editors had no conception of who Hungarians actually were, or why they were being accused of wrongdoings. The stories were usually based on rumors alone and anyway the Hungarians, commonly referred to as “Bohunks,” proved to be defenseless scapegoats.

One such incident, which took place in the early 1890s was known as the “Powderly Affair,” named after a secretary of the Miners’ Union.[17] Powderly waged a campaign against newly-arrived immigrants who were hired as strikebreakers, referring to them in newspaper articles and speeches as “Hungarians.” In fact, the strikebreakers were of many different nationalities-the Hungarians comprised only a small percentage of the group. Powderly waged a propaganda campaign against the immigrant strikebreakers, who were classified as Hungarians. The striking miners directed much hatred and violence towards the unfortunate immigrants. After one day of bloody violence alone, more than a hundred dead were counted in the mining town of Homestead, Pennsylvania.

The Hungarian immigrants were helpless. There was no organization to protect them and no one to defend their rights, until a series of articles appeared in the Chicago Tribune, refuting Powderly’s allegations. The articles documented that only a small fraction of the strikebreakers were Hungarians, and protested such statements as defamatory of all Hungarian-Americans. The series for the Chicago Tribune was written by a native Hungarian, Miklos Komlossy, who later became a prominent newspaper journalist in this country. Due to his efforts, the allegations were dropped. The damage incurred by the Powderly Affair was, nevertheless, not easily forgotten.

In another case, during the flood of Johnstown, Pennsylvania in January 1889, rumors of “Hungarians” pillaging the town and looting graves became widespread. Hungarian-Americans all over the United States, infuriated and incredulous, set up an investigative committee to find out the facts. The results of their findings are contained in the following document:

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Adjutant General’s Office

Johnstown, Pennsylvania, June 20, 1889

This is to certify that the report of the conduct of the Hungarians living in Johnstown has been grossly exaggerated.

They have given me no trouble whatever. They have been obedient to authoritative directions and are on the whole a very well-behaved class of people.

I have no knowledge whatever of the robbing of dead bodies, nor of any lynching of any person in Johnstown by any class of people.

John A. Hiley, Brigade General and Chief of Department of Public Safety.[18]

Around the time of the First World War, fear and hatred of the millions of immigrants entering the United States became uncontrolled. The foreigners became scapegoats for the strikes, social unrest and, above all, the war. Tragic incidents of outright persecution took place, such as Attorney General Mitchell Palmer’s Justice Department roundup of suspected foreign “agitators” in thirty-six cities. Some 6,000 were arrested and detained in concentration camps while five hundred alien “communists” were deported. As it turned out, the raids were coordinated with steel industry efforts to crush the 1919 strike.

Large scale “Americanization” programs instituted in the schools, prompted the “melting pot” solution to the immigrant problem. To attain promotions and enter the professions, the second generation Americanized, or more correctly, anglicized their names and altered their mannerisms. As a result, Hungarian immigrants endured resentment and rejection not only from the strangers around them but often from their own children as well, who were made to feel ashamed of their past.

C.Institutions and Organizations

Around the turn of the century, Hungarian communities were established in numerous cities in the northeastern United States. In the majority of communities the churches were the first to be built. In Hungary, village life centered around the church and church-related activities. Consequently, in the United States the community churches provided a link with the homeland for thousands of struggling immigrants, alone and far away from their land of birth.

According to the United States census of 1920, the 473,538 foreign-born and native-born Magyars were categorized by faith as follows:

| Roman Catholic | 284,122 |

| Reformed | 113,649 |

| Jews | 47,969 |

| Eastern Orthodox | 11,364 |

| Lutherans (Evangelical) | 5,682 |

| Unitarians | 3,220 |

| Baptists, Presbyterians and Others | 7,489 |

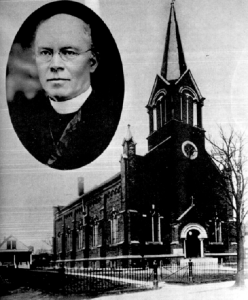

Hungarian immigrants of the Roman Catholic faith, in most cases, organized their own congregations. There was no planning commission to direct the work of the Hungarian immigrants in America, churches simply sprang up wherever congregations were strong enough to support them. Many times twenty-five or thirty families already formed a congregation, then requested a priest, usually from Hungary. The first Roman Catholic congregation to present such a request was in Cleveland, Ohio in 1891. In response, Reverend Charles Boehm was sent to America. Reverend Boehm worked tirelessly to organize congregations and build churches in numerous communities. The first Roman Catholic church built by Hungarians in North America was St. Elizabeth of Hungary Roman Catholic Church in Cleveland, Ohio, dedicated in 1893.

By 1911, thirty-four Hungarian Roman Catholic parishes were already established, located in the states of Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois and Minnesota.[19] In total, Roman and Greek Catholic Hungarian immigrant congregations established approximately ninety churches in America.

The construction of the church was usually financed entirely by the immigrants. One influential community leader and newspaper editor wrote in the early 1900s:

…that in the building of the Hungarian Catholic churches, neither our Homeland, nor the Catholic Church in America gave any financial assistance whatsoever.[20]

The cost of purchasing property and building a church in the 1900s, which also included a rectory and a church hall or school building was around $20,000. When this amount is compared to the meager income of a struggling immigrant laborer (about $1.50 a day), it is surprising to find that so many congregations were willing to take on such a financial burden. Also remarkable was the short amount of time in which these church debts were paid, most were paid in full within seven to ten years.

Roman Catholic Hungarian-Americans constructed schools alongside their churches, which were also financed and maintained by the congregation. Hungarian language parochial schools flourished, especially during the 1920s and early ’30s. Some twenty American cities had full day Hungarian-American parochial schools. Buena Ventura was the first Hungarian Catholic education center. It was founded near McKeesport, Pennsylvania around the turn of the century to prepare nuns for Hungarian language instruction on a parochial elementary level. Most classes were conducted in Hungarian in these schools.

The Great Depression of the ’30s brought a reversal to this situation, however, as church incomes dwindled and the financial upkeep of the schools became virtually impossible. Following the Depression, this problem was compounded by the fact that “the Roman Catholic hierarchy withdrew from active participation in Hungarian-American affairs…”[21] Americanization of the churches gradually took place and the Hungarian congregations could do little to reverse the new policy of the church. Hungarian language instruction in parish schools was not encouraged, which resulted in the gradual dissolution of these classes.

The Reformed Church in the United States was the first to begin work with Hungarian immigrants of the Protestant faith. In 1891, the first two Hungarian congregations of the Reformed church were organized nearly simultaneously in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania by Reverend John Kovacs and in Cleveland, Ohio by Reverend Gusztáv Jurányi. The Hungarian Reformed churches grew quickly, forty-three congregations were organized with over 7,500 members by 1922.[22]

The Magyar Presbyterian Church in America also developed rapidly. The first congregations were organized in 1898 under the leadership of Reverend Julius Hámborszky. By 1922 the Presbyterians had established thirty churches and sixteen missions.[23]

Magyar Reformed churches and Presbyterian churches were already established when, in 1904, six churches elected to become part of Hungary’s Reformed Synod. Some of the ministers believed that the only way to retain a cultural identity was to become part of the Reformed Church of Hungary. Others bitterly protested such a union and much controversy developed over the issue. By 1911, however, the newly-affiliated church, under the leadership of Zoltán Kúthy had expanded into twenty-two congregations.[24] The Reformed Church of the United States and the Magyar Presbyterian Church lost several congregations to the Reformed Church of Hungary. By 1920 the Reformed Church of Hungary had established forty-six congregations, with 9,000 members, thereby becoming “the largest element in Magyar Protestant church life in America.”[25]

Following the First World War, the Hungarian Reformed Church ceased its relationship with Hungary’s Reformed Synod and became the American Hungarian Reformed Church. Today there exist approximately 120 Hungarian Reformed Churches in America, divided into the western, central and eastern districts of the United States. It is the largest of the Hungarian-American Protestant churches. The American Hungarian Reformed Church is independent of other Reformed churches in America. A separate bishop is chosen to guide and coordinate the work of the congregations.

The American Hungarian Reformed Church has strived to maintain the cultural and ethnic identity of the individual congregations. The church has always been an avid supporter of Hungarian language instruction. Between the two world wars, churches in fifty-six cities offered Saturday or Sunday Hungarian language instruction and sixty-eight churches conducted summer school classes.[26] In recent decades, however, that number has been greatly reduced.

The first congregation of Hungarian Jews in the United States was “B’nai Jeshurum,” founded in Cleveland, Ohio in 1866. Initially, Hungarian Jews maintained cultural and social ties with the larger Hungarian-American communities. One of the earliest Hungarian libraries was established by Hungarian Jews in New York City around 1900. Hungarian Jewish immigrants were generally more educated than other Hungarians. Consequently, they frequently provided the professional leadership in business and cultural endeavors initiated on the part of the Hungarian-American community in general. Several examples of this were found in the early Hungarian community of Cleveland, where the first Hungarian doctor and lawyer were Jews who aided other immigrants with guidance, support and free services in times of need. Hungarian Jews were involved in planning the first Hungarian parade in Cleveland and in erecting the statue of Kossuth in 1902.

Hungarian Jews assimilated with greater ease. By the end of the Depression, the majority of Jewish Hungarian organizational and religious leaders withdrew from active participation in Hungarian-American affairs.[27] Many of the children and grandchildren of the first Hungarian Jewish immigrants left the orthodox tradition for temples with more reformed practices. (The majority of the Hungarian Jewish temples established in the United States were orthodox in tradition.) During the 1970s, Hungarian Jewish congregations were still active in New York, Chicago, Detroit and St. Louis.

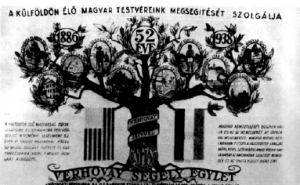

Mutual benefit or self-help societies were among the first organizations established by Hungarian immigrants. They were organized in response to a desperate need for security at a time when, if a worker was maimed or killed in an industrial accident, his family was left destitute. Immigrants in America without dependants also joined because of the funeral benefits. Without membership in such an organization, there was no guarantee one would receive a proper burial.

Initially, immigrants established sick benefit societies for fellow countrymen within their own communities. Some of these societies then expanded, establishing chapters in many parts of the home state or even in other areas of the northeast United States. By the early 1900s, there were mutual benefit societies with religious, political, occupational and homeland district affiliations. According to one author’s estimate, 1,046 Hungarian mutual aid and health insurance societies were active in the United States by 1910.[28]

Despite the fact that the purpose of these groups was basically to provide assistance in times of need, their by-laws and constitutions differed considerably. Some only allowed Roman Catholics or Greek Catholics to join, some only admitted Protestants. The Munkás (Workers) sick benefit chapters disallowed members who were regular church-goers. There was a society which forbade educated Hungarians to serve in any elected capacity. This was undoubtedly in response to numerous get-rich-quick schemes and shady business and real estate deals which were generally perpetrated by Hungarians with more than average education. Many immigrants invested and lost money in such unsuccessful schemes.

One of the largest and oldest national organizations was the Verhovay Fraternal Insurance Association founded in Hazleton, Pennsylvania in 1886. The founder, Mihály Pálinkás, witnessed a Hungarian immigrant, suffering from lung disease, thrown out into the street for not being able to pay his rent. Pálinkás was so disturbed by this incident that he organized the Verhovay with twenty-eight members and a capital of $17.25. The association was named after a member of the Hungarian Parliament, but in the 1950s became the William Penn Insurance Association. By 1945 assets had mushroomed to $7,408,000 with 364 lodges throughout the eastern and midwestern United States.[29]

The second largest was the Hungarian Reformed Federation of America founded in 1896 by Sándor Kalassay with 320 members in Pittsburgh. The federation developed rapidly, growing in members and assets. One of the greatest accomplishments of the federation was the founding of an orphanage and old age home at Ligonier, Pennsylvania after the First World War. The entire project’s initial cost was more than $50,000. The old age home still serves Hungarians today.

Unlike the Verhovay, the Reformed Federation retained its Hungarian character. Hungarian summer school camp has been sponsored each year by the federation, books and educational materials have been published on a regular basis. Scholarships and grants have been awarded to deserving Hungarian-American students. Assets of the federation were reported at $46 million in 1970.[30]

The first Hungarian-language newspaper in the United States, Számuzottek Lapja (Journal of Hungarian Exiles), was founded in 1852 for the purpose of uniting Kossuth’s followers. Another noteworthy Hungarian publication was the Amerikai Nemzetor (American National Guard) founded in 1883 by Gusztáv Erdélyi, who was noted as one of the pioneers of Hungarian-American journalism.

According to estimates from 1852 to 1911, approximately 110 Hungarian-language publications were established in the United States.[31] These newspapers, magazines and journals provided a wide variety of information and news, along with news from the homeland. In addition to the daily newspapers there were publications to suit every type of interest, including denominational or religious bulletins, literary magazines, comic (books), organizational newsletters, political journals, scientific magazines and English-language Hungarian newspapers.

Many of these publications were short-lived, however, having neither the financial support nor the readership necessary to sustain themselves. Those which survived did so by widening their scope in order to appeal to a greater number of Hungarian immigrants. Two became dailies, the Szabadság (Liberty) founded in 1891 in Cleveland, Ohio and the Amerikai Magyar Népszava (American Hungarian People’s Voice) founded in 1899 in New York City.

Szabadság was founded in 1891 by Tihamér Kohányi, who worked tirelessly to keep the financially troubled newspaper in existence. It became a daily in 1906, with peak circulation reaching 40,612 in 1942. More than half a dozen smaller newspapers eventually merged with it. Szabadság played a prominent role in guiding and unifying the opinions and actions of the Hungarian-Americans. The newspaper assisted the immigrant’s adjustment while keeping them in touch with news from the homeland. The editors of Szabadság initiated and involved the Hungarian community in such projects as: erecting a statue of Louis Kossuth in Cleveland in 1902 and gifting the city of Budapest with a statue of George Washington which was erected in City Park in 1906. (Where it can be found even today.)

The Hungarian-language daily, Amerikai Magyar Népszava (American Hungarian People’s Voice), also helped the Hungarian immigrant adjust to life in America. This New York-based daily reached a peak circulation of 27,984 in 1942.[32]

Another Hungarian-language newspaper founded in the 1890s was the Katolikus Magyarok Vasárnapja(Hungarian Catholic’s Sunday), established in 1893. Initially it was the Sunday bulletin of St. Elizabeth Roman Catholic Church in Cleveland. Although the Vasárnap never became a daily, it is one of the oldest Hungarian-language newspapers still in existence today. According to estimates published in the mid-1970s, there are approximately seventy publications (newspapers, periodicals and journals) still serving the Hungarian communities in the United States.

- Leslie Konnyu, Hungarians in the U.S.A.: An Immigration Study (St. Louis: (The American Hungarian Review). , 1967), p. 22. ↵

- John Eppstein, Hungary (Cambridge: (The University Press). , 1945), p. 32. ↵

- Emil Lengyel, Americans from Hungary (Philadelphia & New York: (J.B. Lippincott Co.). , 1948), p. 128. ↵

- Ibid. , p. 127. ↵

- Samuel Joseph, Jewish Immigration to the United States from 1881 to 1910, vol. 59, Columbia University Studies in History, Economics and Law ( (Columbia University Press). , 1914), p. 190. ↵

- Leonard Dinnerstein and David M. Reimers, Ethnic Americans: A History of Immigration and Assimilation (New York: (Dodd, Mead & Co.). , 1975), p. 45. ↵

- Emil Lengyel, op. cit. , p. 129. ↵

- "Nagy Sztrájkok és Szerencsétlenségek." op. cit. ↵

- Miklos Szantho, Magyarok a Nagyvilágban (Budapest: (Kossuth Könyvkiadó). , 1970), p. 66. ↵

- Richard Krickus, Pursuing the American Dream (Garden City, N.Y.: (Anchor Press/Doubleday). , 1976), p. 111. ↵

- "Nagy Sztrájkok és Szerencsétlenségek," op. cit. ↵

- "Milleniumi Magyar Bányász Betegsegélyzo Egylet," Szabadság, 21 December 1911, Part V, p. 5. ↵

- Victor Greene, The Slavic Community on Strike (Notre Dame: (Notre Dame University Press). , 1972), p. 193. ↵

- Richard Krickus, op. cit. , p. 67. ↵

- "Nagy Sztrájkok...," op. cit. ↵

- Leonard M. Dinnerstein and David M. Reimers, op. cit. , p. 45. ↵

- Tivadar Ács, "A Powderly Ugy," Szabadság, 5 October 1948. ↵

- "Nagy Sztrájkok...," op. cit. ↵

- "Az Amerikai Magyar Egyházak Torténete," Szabadság, 21 December 1911, Part IV, pp. 2-6. ↵

- "Az Amerikai Magyar Egyházak Torténete," Szabadság, 21 December 1911, Part IV, pp. 2-6. ↵

- Joshua Fishman, Hungarian Language Maintenance in the United States(Bloomington: (Indiana University). , 1966), p. 11. ↵

- David A. Souders, The Magyars in America (New York: (George H. Doran Co.). , 1922), (reprint edition, San Francisco: R. and E. Research Associates, 1969), pp. 87-88. ↵

- Ibid. , p. 79. ↵

- "Az Amerikai Magyar Egyházak Története," op. cit. ↵

- David A. Souders, op. cit. , p. 79. ↵

- Joshua Fishman, op. cit. , p. 26. ↵

- Ibid. , p. 11. ↵

- According to Géza Hoffmann's data, as cited by Joseph Széplaki, op. cit. , p. 25. ↵

- Emil Lengyel, op. cit. , p. 161. ↵

- 1970 Bethlen Naptar (Ligonier, Pa.: (Bethlen Home). , 1970), p. 41. ↵

- "Az Amerikai Magyar Sajtó," Szabadság, 21 December 1911, Part III, p. 12. ↵

- (Emil Lengyel, op. cit. , p. 203. ↵