Section II: Hungarians in America

From Pre-Colonial Times to the Civil War (1583-1850)

A. The First Hungarians

The first Hungarian in North America was Stephen Parmenius of Buda, who as chief chronicler and historian with the voyage of Sir Humphrey Gilbert, landed on the shores of Newfoundland, Canada in 1583. According to some historians, there was a Hungarian on the continent even earlier. He was known as “Tyrker” and took part in a voyage crossing the Atlantic with Leif, son of Eric the Red in 1,000 A.D. The origins of “Tyrker,” however, are disputed.

Stephen Parmenius was a linguist and historian who was born in Buda in the middle of the sixteenth century. He pursued his studies in other parts of Europe and finally in England, where he met Sir Humphrey Gilbert, half-brother of Sir Walter Raleigh. Sir Gilbert was commissioned by Queen Elizabeth in 1578 to explore and take possession of “any remote, barbarous and heathen lands not possessed by any Christian prince or peoples.” Parmenius wrote a laudatory poem in Latin about Sir Gilbert’s courage and valor. Upon reading the poem, Sir Gilbert requested the young Hungarian humanist to take part in the voyage and record the history of the expedition as chief chronicler and historian.

The expedition left England on June 11, 1583 and landed on the shores of Newfoundland on August 3rd of that year. Parmenius wrote extensively about the voyage and the continent. He wrote detailed descriptions about the climate, vegetation, animals encountered and type of soil. His letters were sent to Richard Hakluyt, an English historian who documented the writings of Parmenius in his book written in 1589.

The return voyage was commenced on August 20, however, only one boat of the three returned to England. On August 29, the boats encountered a violent storm off the coast of Nova Scotia which sank one of the ships with the loss of nearly 100 lives. Stephen Parmenius of Buda was among them. Another ship, which carried Sir Humphrey, was lost near the Azores on September 9. Captain Haie of the Golden Hind, the only ship which did return to England, was one of the few left to recount the unfortunate return voyage. This is what he wrote of the death of Stephen Parmenius:

This was a heavy and grievous event, to lose at one blow our chiefe shippe fraighted with great provision, gathered together with much travell, care, long time and difficultie. But more was the losse of our men, which perished to the number almost of a hundred soules. Amongst whom was drowned a learned man, an Hungarian, borne in the citie of Buda, called thereof Budaeius, who of pietie and zeale to good attempts, adventured in this action, minding to record in the Latine tongue, the gests and things worthy of remembrance, happening in this discoverie, to the honour of our nation, the same being adorned with the eloquent stile of this Orator, and rare Poet of our time.[1]

By 1694 a few Hungarian missionaries were active in America. John Kelp led and founded a religious community in Pennsylvania. A native of Transylvania, Kelp came to America in 1694 with a group of Germans. They settled near Philadelphia, on the banks of the Wis-a-hickon River and formed a community similar to the Quakers, living a life of meditation and prayer. Kelp died there in 1708. The American poet Whittier wrote of the religious leader:

Painful Kelpius from his hermit den By Wissahickon, maddest of good men.

John Kelp’s original place of settlement is part of modern Philadelphia. The historical district is called “The Hermitage” and the street where he lived “Hermit’s Lane.” The Jesuit Order sent missionaries from Europe to work with American Indians. In 1860 a Hungarian Jesuit priest, Father John Rátkai was sent to New Mexico where four years later he was killed by warring Indian tribes.

Another Hungarian Jesuit missionary was Father Ferdinand Konsag or Konschak, formerly a professor who taught in Buda in the early part of the eighteenth century. He was sent to California, where he became head of the St. Ignatius Mission and later visitator to all California missions. Konsag was also a pioneer and explorer, who documented much information about this uncharted territory. He drew one of the first maps of California in 1746.

B. Colonel Kováts and the American War of Independence

Many European nations followed with great interest the struggle between the colonies and England. The conflict gave hope to all European peoples ruled by foreign governments, as in the case of Hungary, dominated by Austria at the time. Hungarians could well understand the hopeless odds of the Continental Army, as they had been at war with their oppressors, Turkish and Austrian alike, for decades. Military experts, volunteers, supplies and countless letters of support and encouragement were sent to the colonies from Hungary as well as other countries. Professor Charles Zimner from Buda wrote to Benjamin Franklin in 1778 that he viewed Franklin “and all the chiefs in your new republic as angels sent by Heaven to guide and comfort the human race.”

Benjamin Franklin was one of the three commissioners sent to France by the Continental Congress in 1776 to secure naval and military assistance. These commissioners were frequently requested to write letters of recommendation for applicants who wished to obtain positions in the American army.

A Hungarian major, Michael Kováts de Fabricy, wrote to Benjamin Franklin with just such a request. Kovats learned of the struggle between the colonies and England, and being a professional soldier, volunteered his services as a commander and organizer of light cavalry.

Kováts was born in 1724 in Karczag, Hungary and was already fighting in a Hussar regiment at the age of twenty. He distinguished himself in the most highly-honored branch of the military in Europe. The Hungarian Hussars were famous for their military expertise and courage, as well as their skill in training and handling a horse. The French light cavalry, as well as the Prussian were initially organized and trained by Hungarian hussar officers. Michael Kovats served meritoriously in countless battles in the Austrian armies of Empress Maria Terezia as well as the Prussian armies of Frederick the Great.

Upon his arrival in America, Major Kováts joined Count Casimir Pulaski, who was then brigadier general and commander-in-chief of Washington’s cavalry. Pulaski’s cavalry was poorly trained. There were few trained cavalry officers which made the task of commanding the forces formidable. On February 4, 1778, Pulaski proposed a plan for the formation of a training division of hussars. In a letter to Washington Pulaski wrote:

There is an officer now in this Country whose name is Kovach. I know him to have served with reputation in the Prussian service and assure Your Excellency that he is in every way equal to his undertaking.[2]

Later, in another letter to Washington dated March 19, Pulaski again recommended Kovats:

I would propose, for my subaltern, an experienced officer, by name Kowacz, formerly a Colonel and partisan in the Prussian service.[3]

Pulaski’s legion was commissioned by the Continental Congress on March 28, 1778 and Michael Kováts was named colonel commandant of the legion on April 18, 1778. He was finally given the opportunity to perform the task he had originally intended: to organize and train hussar regiments for the American army. The recruiting of men began almost immediately and by October 1778, the legion consisted of 330 officers and men. Kováts trained these men in the tradition of Hungarian hussars: in basic form, training and organization they were similar to their European counterparts.

The legion was transferred to New Jersey and in October was sent into battle with the British at Osborne Island on the 10th and at Egg Harbor on the 14th. With the approach of winter, the legion was ordered to Cole’s Fort, where they spent the first part of the winter in training.

On February 2, 1779, the legion marched to South Carolina to join the forces of General Benjamin Lincoln. During the long march smallpox took its toll: only 150 soldiers arrived in Charleston—more than half of the legion had died of smallpox along the way.

Charleston was under siege by the British. The situation was critical, the population urged for surrender. Pulaski’s legion arrived on May 8, 1779 and unsuccessfully attacked the English troops led by General Prevost on May 11th. In the battle on May 11, 1779 in Charleston, South Carolina Colonel Michael Kováts lost his life in the war for American independence. He was buried where he fell. Even according to the English, the legion was “the best cavalry the rebels ever had.”[4]

Colonel Michael Kováts was an American military hero of foreign birth to be remembered with the Polish Pulaski, the German Von Steuben and the French Lafayette, who believed in the cause of American independence and were willing to give their lives to help attain it.

Kovats was the only Hungarian known to have served in the Continental Army; however, there were numerous Hungarians who took part in the American War of Independence with the French troops sent to aid the colonies in 1776.

“Lauzun’s Foreign Legion” was one of the troops made up of primarily foreign volunteers. The legion consisted of infantry and cavalry; the cavalry of 400 men was further divided into a squadron of lancers and a squadron of hussars. It has been estimated that, discounting officers, 140 men in the squadron of hussars were Hungarian. Taking into account that many hussars in French service at this time were from Hungary, this figure is not surprising. Lauzun’s Legion served until the end of the war. The cavalry was noted in particular for serving with distinction. Two Hungarian officers were mentioned as enlistments in Lauzun’s Foreign Legion: Major John Polereczky in the squadron of lancers and Lieutenant Francis Benyowsky in the squadron of hussars. The Polereczky family received Hungarian nobility as far back as 1613. Following the American Revolution, John Polereczky settled in Dresden in the state of Maine. Francis Benyowsky died in America in 1789.

C. Explorers, Writers, Adventurers

Numerous Hungarians journeyed to the United States in the years following the revolutionary war. For the most part they were adventurers who came out of curiosity. Some traveled the new country for a few months or even years and returned to Hungary, eager to relate all they had seen and experienced. The majority of those who stayed were successful at building a new life for themselves.

Baron Majthényi visited the United States out of interest. When he returned to Hungary, he introduced the maple tree and the boiling down of its sap into syrup as he had seen it done in the United States on his estates at Abaújfüzér and Radvány. Benjamin Spitzer was a well-known merchant in New Orleans in the 1780s. Spitzer emigrated from Old Buda and sought to establish trade relations between Hungary and the United States. Dr. Charles Luzenberg came from Sopron and settled in New Orleans in 1829. He joined the medical staff of Charity Hospital and became the founder and first president of the New Orleans Medical Society.

Charles Nagy, noted astronomer and mathematician, arrived in the United States in 1832. He established permanent ties between the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the American Philosophical Society founded by Benjamin Franklin. He gained the friendship of President Jackson and was made an honorary citizen of the city of Philadelphia. When he returned to Hungary, the following incident occurred; when the Austrian police searched his home in Bicske in 1849, they found a small red, white and blue American flag underneath his mattress. This was considered high treason in those days.

Samuel Ludwigh, a native of Koszeg, came to this country in 1837 and lived in Philadelphia and Baltimore. He was a lawyer by profession, but soon became a writer and lecturer, editing a German-language newspaper in Philadelphia. At the end of the Hungarian War of Independence (1849), he wrote several articles entitled “Hungary and Hungarian Sketches” in Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune. In the 1850s Ludwigh became publisher and editor of an English-language periodical, The Torch.

Attila Kelemen, a tailor from Hungary, immigrated to the United States and invented a cure-all known as “Tinctirus Papricus.” Kelemen sold thesubstance, which was nothing more than a mixture of paprika and whisky, as a cure for cholera. His “medicine” was so successful, that according to Hungarians who visited Kelemen in New York, he had obtained a position as a medical doctor and became the owner of a large hospital and pharmacy on Broadway.

One of the earliest letters sent to Hungary from America was written by Gáspár Printz, who settled in Baltimore, Maryland in 1803. In the letter, dated January 7, 1818, Printz wrote:

…This is a free country, we have no king, but a president. Here a man can choose the means of supporting himself. No man is better than the other, as we are all noblemen here. People do not take off their hats to one another, the poor man is equal to the rich man. Our country is a free republic.[5]

Extensive eyewitness reports about life in America were written by three Hungarians: Alexander Bölöni Farkas, Agoston Haraszthy and John Xantus. After a year of traveling in the United States, Alexander Bölöni Farkas wrote Traveling in North America (1831), which dealt with the political, educational and social aspects of life in this country. Agoston Haraszthy, renowned entrepreneur, wrote a book published in 1844 entitled, A Journey in North America. Haraszthy emphasized the commercial and practical aspects of American life. The correspondence of John Xantus, naturalist and explorer, was compiled and published in two books, Letters from North America (1857) and Travels in Southern California (1859). Both works dealt with life in the unsettled west and southwest.

Alexander Bölöni Farkas was a young Hungarian writer who covered more than 2,450 miles of the United States in 1831 as the secretary of Count Ferenc Beldy. When he returned to Hungary he compiled his writings in Travels in North America, published in Kolozsvár in 1835. It reached two editions in the first year. The perceptively written book dealt with many aspects of American life, in particular with the political, educational and social structure of the new democracy.

This country made a lasting impression on Bölöni Farkas. In Washington he was received by President Jackson, along with two other Hungarians; they were the first Hungarians to be received at the White House. In several places along his journey he met Hungarian merchants, travelers and adventurers. Bölöni Farkas wrote about these fellow countrymen and his varied experiences. The book reflects a fond admiration and respect for the United States. His writings often brought attention to the archaic ways of Europe when compared to the United States. He was impressed by the public school system, the libraries and by the multitude and different types of newspapers and journals.

…there is no standing army! No privileged class or nobility! There are no titles… There is no secret police! But there are schools, libraries, museums, scientific institutions, …and above all newspapers and journals.[6]

Travels in North America related the workings of democracy and was widely read in Hungary. The book portrayed an image of the United States as a “happy fatherland, where everyone is equally born into freedom and independence.”

Agoston Haraszthy was a native of Hungary who led a very colorful life in the United States. He was a talented writer. After touring the United States in 1840 he wrote a book about his experiences which was published in Hungary in 1844. The book, entitled, A Journey in North America, emphasized the commercial and practical aspects of American life.

Haraszthy was a pioneer and explorer. He bought, jointly with an Englishman named Bryant, 10,000 acres of the Territory of Wisconsin and founded a town called Haraszthyville. Later, this became the site of Sauk City, Wisconsin.

In Washington Haraszthy and his wife were celebrated socialites. They were received by President Tyler; Daniel Webster, the great American orator and statesman, arranged dinner parties in their honor on numerous occasions.

Haraszthy was a renowned entrepreneur. Some of his ingenious business ventures included: running a steamboat on the Missouri and a ferry on the Wisconsin River, opening a general store in Haraszthyville and in Baraboo, a short distance away, building houses with brick burnt in his own kilns and planting the first hop-yard in Wisconsin. Moreover, he was appointed to melt and refine the United States Mint.

Ágoston Haraszthy served in various official capacities. He was twice elected vice president of the Wisconsin Historical Society. He led an immigrant association sponsoring settlers from England, Germany and Switzerland. Haraszthy was elected sheriff of the county in which he resided in San Diego, Calfornia. It was neither an easy nor safe job to hold in such unsettled territory. Subsequently, a street was named after him which to this day can be found in the city of San Diego. He was elected to the legislature at Sacramento in 1850.

Haraszthy’s most outstanding contribution was made to the development of California’s wine producing industry. He was named the “Father of California’s Viticulture” for the many new and innovative methods he discovered. He was the first to introduce a wide variety of grapes from Europe, including the famous California Tokay, originally from Hungary. Haraszthy was appointed the State Commissioner for Viticulture and wrote a book entitled, Grape Culture, Wines and Wine-Making. With Notes upon Agriculture and Horticulture, published by Harper Brothers in New York in 1862.

Janos (John) Xantus immigrated to the United States in the 1850s. He lived in this country for only thirteen years, during which time he attained renown as a naturalist and explorer, collecting all forms of birds, fish, mammals, insects, reptiles and plants never before documented.

Born in Csokonya, County of Somogy, Xantus studied law. He served as a lieutenant during the Hungarian War of Independence and when it failed, immigrated to the United States. Xantus landed in New York with $7 in his pocket. He tried many times without success to obtain a position commensurate with his high degree of education and intelligence. Xantus found himself earning a daily wage through odd jobs, which often meant digging ditches, up to his waist in water for days. After months of unsuccessful searching, a discouraged Xantus wrote: “…speaking six languages, playing piano and being a good topographical draftsman, after all efforts, I could never bring my existence higher up than to $25 a month.”[7]

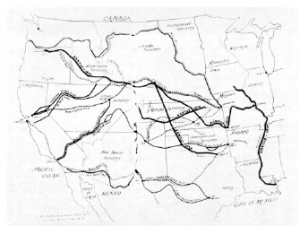

In 1852 Xantus was hired as a cartographer for the Pacific Railroad. He was assigned to travel with a group through the western United States in search of the best railway route from St. Louis to California. During the expedition, Xantus devoted all his free time to writing detailed descriptions of the land, climate, vegetation, animals, towns and people they encountered. In particular, he described the Indian tribes in meticulous detail, making drawings of their weapons, clothes and customs.

Xantus wrote about his adventures in America in letters sent to his family in Hungary. He indulged in some self-aggrandizement in his early letters, being unable to admit to initial failures. For the most part, however, they were interesting and informative accounts of the people, customs and life-style in North America in the mid-1800s. In 1865 the letters were compiled and published in Hungary in a book entitled, Letters from North America. Later, a second book, Travels in Southern California, was published, based on his experiences in the southwestern part of the United States. The books were successful and earned Xantus acclaim in his native country. His writings captured the untamed excitement of the West:

The California horseman in many respects resembles the Andalusian knights of De Vega or Cervantes. He wears a wide-brimmed peaked hat, a silver-braided dolman, trousers slit at the side from the knee down, revealing red socks underneath, and he sits on a saddle decorated with peacock feathers. The jackboot is armed with huge spurs which are fastened to the heels with heavy chains-the clinking sound can be heard a half mile away. Ordinarily he carries on the pommel a pistol with a long barrel, trimmed with fox or squirrel tail, and a sharp dagger; sitting thus in the saddle, he no doubt believes his is nothing less than ‘California’s pride and the scourge of the terrified universe.[8]

In 1855, in a desperate attempt to obtain a reliable source of income, Janos Xantus enlisted in the army as a private. He was so ashamed of this action that he used an assumed name. It was while he was in the army that his fortunes improved. He served at Fort Riley in Kansas where he met Dr. William A. Hammond, who recognized the intelligence and talent of Xantus and introduced him to the procedures of collecting and preserving natural specimens. In 1856 the distinguished Philadelphia Academy of Sciences elected Xantus to life membership.

Xantus obtained a transfer to Fort Tejon, California through the influence of Spencer F. Baird, secretary of the Smithsonian Institute. He was promoted to the rank of hospital steward, which enabled him to devote more time to his collections. Fort Tejon was located in territory which was uncharted by naturalists, the region of the great Central Valley of California and the Sierra Nevada. The work of Xantus in this region proved to be of immeasurable importance. Within eighteen months, he had sent twenty-four cases of preserved specimens to the Smithsonian, “…including nearly 2,000 birds, 200 mammals, many hundreds of birds’ nests and their eggs, and large numbers of reptiles, fishes, insects, plants, skulls, skeletons, etc., all in the highest condition of preparation and preservation, and furnishing such accurate and detailed information of the zoology and botany of Fort Tejon as we possess of but few other points in the United States.”[9]

After receiving a discharge from the army, Xantus took up new duties as a tidal observer for the US Coast Survey near Cape San Lucas, where he explored the flora and fauna of an area extending over 350 miles. His accurate documentation was lauded on several occasions by colleagues at the Smithsonian.

The Crotalus lucifer is easily recognizable, and it is just as well, for it is the most aggressive and venomous of the species. The color is shiny black with tiny, pale yellow intersecting squares stretching the length of the body. The fully-grown specimen is five feet long. When it reaches this stage it no longer grows in length but in bulk. I killed an exceptionally fat specimen. Its length was four feet ten inches, the neck four and a half inches and the waist ten and a half inches thick. I found two undigested hamsters, hair and skin intact, in its stomach, which accounted for the unusual bulk.[10]

In 1861 Xantus visited Hungary, where he was given a hero’s welcome. He was named honorary president of the Zoological Gardens at Budapest and was elected to membership in the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The following year, Xantus returned to the United States and was appointed U.S. consul, taking up his duties in Manzanillo, Mexico. Next to his consular duties, he collected and documented the natural wildlife of another unexplored area, the Pacific slope of the Sierra Madre. In 1864 Janos Xantus returned to Hungary where he became the first director of the Budapest Zoo and later, curator of the ethnographical section of the Hungarian National Museum.

Through the descriptive writings of Xantus, the Hungarian people obtained first-hand information and insight into North American life. The collections of Xantus made a substantial contribution to the scientific knowledge of the United States. Moreover, his work initiated an exchange between the Smithsonian Institute and the Hungarian National Museum. Xantus was described by one colleague as “the most accomplished and successful explorer in the field of natural history I have ever known or heard of, the results of his operations enriching the Smithsonian Museum in a very high degree.”[11]

- David B. Quinn and Neil Cheshire, The Newfoundland of Stephen Parmenius, The Life and Writings of a Hungarian Poet, Drowned on a Voyage from Newfoundland, 1583 (Toronto: (University of Toronto Press). , 1972), pp. 59-60. ↵

- Eugene Pivány, Hungarian-American Historical Connections from Pre-Columbian Times to the End of the American Civil War (Budapest: (Royal Hungarian University Press). , 1927), p. 21. ↵

- Ibid.p.21 ↵

- Coloman Révész, Colonel Commandant Michael de Kováts, Drillmaster of Washington Cavalry (Pittsburg: (Verhovay Fraternal Insurance Associations). , 1954), p. 12. ↵

- Géza Kende, Magyarok Amerikában (Cleveland: (Szabadság). , 1927), p. 33. ↵

- Havasne Bede Piroska es Somogyi Sandor, eds., Magyar Utazók, Földrajzi Felfedezok (Budapest: (Tankönyvkiadó). , 1973), p. 148. ↵

- Theodore Schoenman and Helen Benedek Schoenman, eds., Letters from North America (Detroit: (Wayne State University Press). , 1975), p. 18. ↵

- Theodore Schoenman and Helen Benedek Schoenman, eds., Travels in Southern California (Detroit: (Wayne State University Press). , 1976), p. 43. ↵

- Schoenman, Letters from North America, pp. 20-21. ↵

- Schoenman, Travels in Southern California, p. 37. ↵

- Ibid. , p. 15. ↵