Section I: History of Hungary

Reconstruction, Reform, and the War of Independence

The eighteenth century ushered in an era of relative peace, during which no major wars or revolutions touched Hungary’s borders. For this reason it was known as the “Era of Reconstruction.” It was also an era of stagnation and national decadence. Hungary’s cultural and economic evolution was overshadowed by Hapsburg rule. The immediate successors to Charles III, Maria Theresa (1740-1780) and Joseph II (1780-1790) made every attempt to pacify and win over the Hungarian nobles, lest another uprising disrupt the unity of the Empire. The nobility was bestowed with many privileges while the dire needs of the middle and peasant classes were ignored.

Hungary’s population was restored somewhat from the disastrously low level of two and one-half million following the wars of liberation to over nine million towards the end of the eighteenth century. The Turkish Era was in large part responsible for Hungary’s transformation. from the homeland of the Magyars to a multinational state. The Turks devastated the most densely populated Magyar areas, namely the southern and central plains area of Hungary. These evacuated areas were resettled with southern Slav groups, namely: Serbs, Vlachs and Croats fleeing from the Turkish advance. The Hapsburgs instituted a systematic method of colonization known as the Impopulatio whereby Germans, along with numerous other ethnic groups were granted generous incentives to settle in Hungary. The impoverished Magyar people, after enduring nearly two centuries of continuous warfare, were given no such assistance.

Economic growth was seriously hampered by Austrian restrictions; Hungary was relegated to the position of producer of raw materials within the Empire. Hungarian entrepreneurs were virtually non-existent; the nobility was ingrained with the belief that landowning and soldiering were the only occupations befitting a nobleman. As a result, what little trade and industry existed in Hungary was in the control of non-Magyars. Austria was given every advantage in trade with Hungary; Austrian goods entered Hungary nearly tax free while the latter’s exports to Austria were overtaxed. Even with regards to agricultural exports, Hungary was restricted.

Hungary’s backwardness was most evident in the countryside where profitable farming was only possible on the estates of a few enlightened landlords. Yet, the only mode of existence for the majority of the population was farming. In the plains area flooding caused by unregulated rivers isolated large tracts of land—some roads were impassable for most months of the year. Viticulture was prevalent in numerous towns including Buda. Gold and silver mines were nearing exhaustion while the mining of coal was in its initial stages of development.

Whatever advantages there were to be gained by Hapsburg connections were reaped by the nobility. Empress Maria Theresa invited the Hungarian magnates to the court and by granting various privileges, managed to win them as ardent supporters of the monarchy. They were given positions in the central, diplomatic and military branches of the government. The Theresianum, a prestigious academy for the sons of the aristocracy was founded. For the lesser nobles the Royal Hungarian Bodyguard was established; each county sent two young men of noble birth to become part of it.

Land in Hungary was cheap and much of the land evacuated by the Turks or confiscated during Leopold’s reign was redistributed, often as reward for services rendered the Crown. In this manner many estates were acquired by foreigners. By the end of the eighteenth century, one-third (1/3) of the land in Hungary was owned by approximately 108 aristocratic families. The richest, Count Eszterházy, owned a sumptuous estate in western Hungary. His protégé, Haydn, organized nightly performances of opera and comedy. During Maria Theresa’s reign alone, over 200 great palaces were built in Hungary.

The national character of Hungary diminished during this period. Magnates of Magyar origin spent most of their time in Vienna, becoming increasingly germanized with each generation. The majority spoke little Hungarian, let alone take any real interest in their country’s affairs. Moreover, this class was free of all forms of taxation. The heavy burden of Crown taxation was carried by the peasantry and middle class. The magnate class jealously guarded this privilege as their exclusive right, thereby retarding the growth and development of the country for well over a century.

The first half of the nineteenth century brought about an awakening of Hungarian national consciousness, inspired by the French Enlightenment and numerous populist and nationalist revolutions sweeping Europe. Hungarian translations of revolutionary French and English texts were smuggled into the country and widely read. A new generation of intellectuals and writers came to the forefront, advocating liberal, social and political reforms.

One aspect of the movement for a distinct Hungarian culture was the renewal of the Magyar language, spearheaded by György Bessenyei, a member of the Royal Hungarian Bodyguard. This movement was expanded by, among others, Ferenc Kazinczy. Hungarians strove towards self-determination through, first and foremost, the use of their own language in lieu of German and Latin. In 1844 Magyar was made the official language of the country and the ranks of linguists, poets and writers swelled. This era was marked by the large scale expansion and development of Hungarian literature.

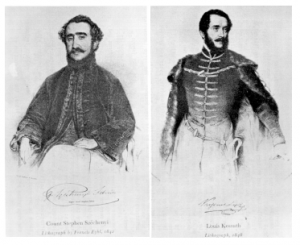

The cultural revival of the country was further enhanced by the endowment of the National Museum by Ferenc Széchenyi and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences by his son, Stephen. The large landowning aristocratic Széchenyi family was indeed unique; the most famous member, Count Stephen Széchenyi, was named the “Greatest Hungarian” because he implemented comprehensive economic and social reforms and did more to modernize Hungary than anyone. Stephen Széchenyi was an enlightened aristocrat who travelled widely especially to England where the industrial revolution made a deep impression on him. In his books: Hitel (Credit) (1830), Vilag (Light) (1831) and Stádium (1833), Széchenyi put forth a workable program of reform and pointed to the arrogance and selfishness of the magnate class as the greatest hindrance to progress. A few of Széchenyi’s far-reaching projects included: the regulation of the rivers Danube and Tisza, the introduction of steamship navigation on Lake Balaton and the Danube, the construction of the first permanent suspension bridge over the Danube linking Buda and Pest, initiating horse racing in Hungary and founding the first national casino. Széchenyi was the first to envision Budapest as the social, cultural and industrial hub of the country.

By the early 1800s, liberal ideas and the urgency of reform had captured the imagination of nearly all social classes in Hungary. The country was divided, however, as to how these reforms were to be made. The two main opposing views were: severing all political connections with Austria and forming an independent Hungarian government versus maintaining limited ties with the Hapsburgs in order to use the economic advantages to institute reforms. The two great advocates of these views, Lajos Kossuth of the former and Stephen Széchenyi of the latter, played dramatic roles in Hungary’s social and political evolution during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Lajos Kossuth was a lawyer, who as proxy for an absentee noble in the lower house, embarked upon his career as journalist and politician by issuing the Parliamentary Letters, an unofficial journal of the proceedings. Until that time no written records were kept of the debates. Kossuth was imprisoned by the Austrians for his liberal views, however, this incarceration only made the young reformer and his writings more popular. After receiving amnesty Kossuth continued pressing for total independence from Austria as editor of the Pesti Hírlap. Kossuth was by now a national hero. The brilliance of his editorials, expounding on the reforms needed, sent the circulation of the Hírlap soaring.

On March 15, 1848, inspired in part by the revolutions in Paris and Vienna earlier that year, a bloodless revolution broke out in Budapest led by young writers, lawyers and university students. Hungary’s greatest men of literature were among them: the poets Sándor Petofi and János Arany, along with Mór Jókai, the best known novelist of the nineteenth century. The revolutionaries printed and distributed Petofi’s revolutionary poem, the “National Song” and the national demands for change or “Twelve Points.”

The latter included demands for a national government, freedom for serfs, abolition of taxation privileges and freedom of the press. Under pressure of the revolution, laws were approved in Vienna for the formation of an independent Hungarian government headed by Count Lajos Batthány.

The newly established independence of the Magyars was consequently challenged by Hungary’s national minorities, who pressed for their own rights and liberties. The Language Law of 1844, which made Magyar the official language of the country, embittered the Slav minorities, who until then enjoyed relative autonomy and unrestricted use of their own language. Dissent was further instigated by Austria, who urged the minority groups to take up arms against the Magyars.

The Croats did not wait for the new Hungarian government to deal with their demands. In September 1848, barely six months after the formation of the independent government, Jellacic, the Ban of Croatia, invaded Hungary from the south with an army of 45,000. This was one part of a three-pronged attack directed by the Austrians from the west, east and south. Hungary’s hastily formed army, the Honvéd, with barely 25,000 recruits defeated the Croat forces shortly afterwards. The struggle continued. Through the superb oratory skills of Kossuth in recruiting soldiers and the tactical genius of such military leaders as Arthur Görgei and General Bem, the Magyars regained all territories occupied by the Austrians by spring 1849. On April 14 Hungary was proclaimed an independent country and Kossuth was elected governor of the new republic. This was achieved by the Magyars acting for the most part on their own—the only assistance they received came from a few thousand volunteers from various other countries. In particular the Poles assisted in significant numbers; 3,000 Polish volunteers took part along with numerous Polish army officers.

In a final attempt to crush the War of Independence, the Austrians negotiated with Czar Nicholas I to obtain Russian intervention. In July 1849 three armies invaded Hungary: the Austrians from the west, the Russians from the north and the Croatians from the south. In the face of such overwhelming odds, the Magyars surrendered to the Russians at Világos in August. They were handed over to the Austrian General Haynau, who carried out sadistic vengeance. Thirteen Hungarian generals were hung on October 6, 1849 at Arad and more than four hundred military leaders were imprisoned. One hundred political leaders were also executed and atrocities were committed against the defenseless Magyar population.

Lajos Kossuth went into exile to Turkey and until his death continued campaigning for Hungarian independence. His tours to England and the United States evoked empathy and admiration for the Hungarian cause. Some 4,000 emigrés and their families settled in the United States around the early 1850s.

In July 1850 Haynau’s reign of terror ended, followed by Austrian occupation and absolutist rule, which lasted nearly two decades. The Magyars adopted an attitude of passive resistance to the oppression which characterized this era: massive bureaucracy, a network of Austrian agents and spies and excessive taxation.

The cost of maintaining such a powerful grip on Hungary proved to be a great strain on Austria, who was concurrently embroiled in various disputes in other parts of the empire. In 1866, pressed by the disastrous outcome of the wars with Prussia, Emperor Francis Joseph entered into negotiations with the Hungarians. The negotiations, led by Ferenc Deak, resulted in the Compromise of 1867 which ushered in a new era, the Era of Dualism, wherein Hungary became an equal partner in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The compromise returned to Hungary her status of sovereign state and granted independence in internal affairs. Foreign affairs and defense were common with Austria. In trade the monarchy formed a single customs unit. A responsible Hungarian government was established in February 1867 under the leadership of Count Julius Andrássy. Transylvania was returned to Hungary.

The peace and political stability of the times brought prosperity and economic development. Industry and commerce gained momentum; new banks and factories were established and agricultural improvements were initiated. Large scale projects such as the construction of a national railway system, linking the farthest points of the country and the regulation of rivers and building of canals were completed. The mining of coal and production of steel increased significantly. Hungary gained international recognition in the manufacturing of railway engines and steam turbines. Other industries such as flour milling, sugar refining, distilling and leather tanning flourished.

The millenium (one thousand years) of Magyar settlement in the Carpathian Basin was commemorated throughout Hungary in 1896 with the dedication of monuments, parks, bridges and public institutions. In Budapest a grand Millenary Exhibition was inaugurated in City Park and the Körút or Great Boulevard was opened. The Budapest underground—the first of its kind on the continent-was completed.

The unrestricted growth of capitalism was not accompanied, however, by reforms in the working conditions of industrial and agricultural workers. The average working day was ten to fourteen hours, safety and health regulations were generally ignored, housing standards were non-existent and women and children were exploited in labor. Compounding the problems of the working class was a phenomenal increase in population, from thirteen million in 1850 to nearly twenty-one million by 1910.

Land reform was desperately needed. One-half of the total rural population remained landless while one-third of the arable land in Hungary was owned by fewer than 4,000 proprietors. Emigration relieved the strain somewhat, over one million Hungarians migrated to the United States around the turn of the century. Although the organization of unions was suppressed, some advances were made. One reformer, Count Alexander Károlyi instituted the First Farmers Co-operative and a Central Credit Society in 1898.

Hungary’s national minorities were infected with the militant nationalism which permeated Europe in the early 1900s and which ultimately led to the First World War. Hungary issued the Bill of Nationalities in 1868, granting equal rights before law to all nationality groups living within territorial Hungary. Despite this a new generation of radical minority leaders, encouraged by signs of support from Austria and/or Russia, pressed for complete independence from Hungary. They wanted their own independent state, not minority protection. Each wished to be the ruling nation over numerous other nationalities which would inevitably become part of the same area.

The Pan-Slav movement depicted the Hungarians as the oppressors of central Europe. The exaggerated allegations about the “magyarization” of the nationalities were made to justify the minorities’ claims for separation. Because foreign affairs were headed by one minister common to both Austria and Hungary, Hungary was unable to effectively counteract the defamatory campaign. As it turned out, the new states created out of territorial Hungary after the First World War in many ways compounded rather than solved the problems of minority nationalities in central Europe.