Section III: The Hungarian Communities of Cleveland

The Buckeye Road Hungarian Neighborhood (1920-1960)

A. THE AMERICAN DEBRECEN

The Buckeye Road Hungarian Community was a transient neighborhood until 1920. Immigrants came and went-worked for a few years to save money, lived in boarding houses and generally were not really concerned with establishing anything of permanence. This situation was altered dramatically, however, by World War I and the Treaty of Trianon, which imposed harsh economic and political conditions on Hungary. The plight of the homeland had a dramatic affect on Hungarian immigrants living in the United States. Suddenly the decision to return or remain was imminent. More than half of the one million Hungarian immigrants living in the United States returned to Hungary during and after the First World War.

Hundreds of incidents, related by residents of Buckeye, conveyed the many obstacles and disappointments faced by those who returned. Many returned and bought land, only to find that they couldn’t keep it because of political changes, economic hardships and/or the taxation system. One community of many, the Hungarians of Middletown, Ohio left en masse after the War; the town was left with virtually no Hungarian residents. One Szekler-Hungarian immigrant returned to his family in Transylvania, partitioned to Rumania, and found that his wife wouldn’t speak to him or let him in their home. He finally learned the reason for her anger: the family had not received any of the money which he had promised to send from America. The immigrant was devastated by this news as he had taken all of his earnings to an “official” currency exchange-transfer agent; he had been under the impression that the funds were being sent to his family.[1]

One Buckeye Road resident, Mrs. Bertha Ludescher, was three years old when she was first brought to America in 1907. She met her husband, also a Hungarian immigrant, was married and returned with him to Transylvania in 1920. Mrs. Ludescher recalled this period in her life as being pleasant; her husband’s relatives were very kind to her and they were relatively happy. Some things were difficult to comprehend however, such as not being allowed to speak Hungarian in the streets in an area of Hungary which was now part of Rumania.

Difficulties arose when the Rumanian government wanted to draft her husband into the army. Bertha Ludescher wrote to her parents in Pittsburgh for assistance. They sent the young coupl $600 to save their son-in-law from the forced military service. The Rumanian government, upon receiving the money, which was at that time an enormous amount, issued an official certificate stating that Ludescher was free of all military duty and could not, from that time forward, be called for service.

Not even one year passed when Ludescher was again called for military service. Again, the parents in America were notified of the situation; this time they sent $400. Mrs. Ludescher later realized that even $100 would have been enough to satisfy Rumanian officials, who took the money each time as an excellent illegal source of American currency. The $1,000 was not enough, however, after receiving two “official” documents guaranteeing Ludescher’s freedom from military service, he was called in again the third year. The parents in America as well as the young couple finally grew tired of the bribery and deception and Ludescher hurriedly left Rumania with a forged passport to Argentina. Because of the Quota System, Bertha Ludescher could not rejoin her husband in the United States until 1930, more than seven years later.[2]

Approximately half-a-million Hungarians stayed and made permanent homes in the United States. Thousands did so upon learning that their villages were under foreign rule or because they received countless pleas for aid and letters describing the poverty and suffering. They realized they could be of greater assistance by saving and sending home their earnings. In the case of the Cleveland Hungarian Community, World War I and the effects of the Treaty of Trianon were the two most significant factors which decided the fate of this ethnic enclave. It was due to these factors that the east side Hungarian community developed into a unique ethnic neighborhood and remained self-contained and distinct for nearly five decades.

The stability of this unique Hungarian neighborhood was signalled by the following indicators: after 1920, an increasing number of residents purchased their own homes and became citizens of the United States. Only fifteen percent of Hungarian immigrants took out naturalization papers prior to World War I, as compared to about thirty percent following the War. By 1930, this percentage had increased to 55.7 percent.[3] The original Hungarian neighborhood around East 79th Street and Holton Avenue expanded from Buckeye Road until Woodland Avenue and East 72nd Street, from Woodhill Road until East 125th Street. At the time of the construction of the Pennsylvania Railroad through this section, Hungarians moved eastward to the other side of Woodhill Road, as far as 140th Street, where living conditions were “considerably better.” Their stay seemed permanent and they were intent on making the best of it. They expanded east along Buckeye Road, building homes and establishing businesses.

Hungarian businesses soon dominated the entire span of Buckeye: around East 79th Street and Holton Avenue, on lower Buckeye from East 79th to Woodhill and upper Buckeye from East Blvd. to East 130th Street.

Hungarian real estate brokers encouraged their fellow countrymen to buy homes in this area. In particular, the owners and operators of the South Woodland and Rice Avenue Allotment Company: John Weizer, Ferenc Apáthy, Joseph Szepessy and John Gedeon, among others, were instrumental in moving Hungarians into the Buckeye Road area. Weizer alone sold more than 2,000 building lots to Hungarians. In Hungary, home and land ownership was a symbol of status and this attitude was reflected by the Hungarian immigrants in America. Once it was established that their stay was permanent, home ownership became a top priority and pride was taken in keeping the house and property in good order.

The 1920s and early ’30s were boom years as far as Hungarians in Cleveland were concerned. The Buckeye Road Hungarian Community was built in its entirety during these years with most of its present churches, businesses and office buildings. Never before, or since was so much accomplished. The immigrants built themselves a Hungarian town, in memory of the hundreds of towns and villages they could never return to and made it their new home-a little Hungary-5,000 miles away from home.

In determining the stages of the history of the Buckeye Road Hungarian Community, 1920 to 1930 is known as the period of expansion, while 1930 to 1965 is designated as the period of stability.[4] By the end of the 1930s, the Buckeye area had a population of approximately 40,000, of which Hungarians constituted about 35,000. The concentration of Hungarians in this one area was so great that for several decades Cleveland was considered the city with the second largest Hungarian population in the world, after Budapest. The Buckeye neighborhood was deservingly named the American Debrecen; Debrecen was the second largest city in Hungary at the time.

B. THE UNIQUE “SUB-CULTURE” OF BUCKEYE

By 1920, Cleveland’s Hungarian population had reached 43,134; Hungarians constituted eighteen percent of the city’s foreign-born population.[5] The Buckeye Road Hungarian Community was a unique phenomenon, nowhere else in the United States were there so many Hungarians concentrated in one neighborhood. Immigration from Hungary was literally halted by the Quota System of 1924, and the next wave of immigrants did not arrive until after World War II. These Hungarians became isolated from their homeland as well as from the general American public and as a result, a unique sub-culture developed which was exclusive of “Buckeye Hungarians”.

Immigration presented a two-fold transition for the Hungarians who immigrated at this time: from native to foreign country and from rural to urban surroundings. Due to the en masse nature of immigration to Cleveland and the creation of the Hungarian neighborhood, however, the “old country” village customs and attitudes were transplanted to Buckeye Road. The ethnic enclave helped many cope with the drastic changes and alienation which are so much a part of the immigrant experience.

The neighborhood was expansive and the number of Hungarians significant-one was not reminded of the fact that this was indeed a foreign country. The children playing in the streets spoke Hungarian. Businesses and all services were provided by fellow countrymen. The heritage, customs and attitudes of the old-timers were cherished and preserved within the community. The immigrants who toiled in steel mills or factories were usually surrounded by other Hungarian workers. Often even the foreman would be a fellow countryman. Peddlers who came in from the farms were compelled to learn a basic knowledge of Hungarian in order to sell their produce successfully on Buckeye Road. Hungarians on Buckeye to this day insist that the Black bus drivers who drove the Buckeye Route could understand and converse with the Hungarian riders.

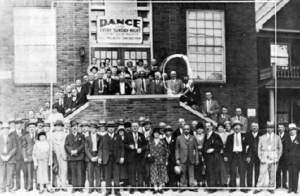

Hungarians thrived during these years on Buckeye. Community and social events were of such magnitude and multitude that the neighborhood could truly be described as a dynamic, ethnic entity. Seven churches of six denominations were built by the community, in addition to three synagogues. The facilities of these churches were in constant use, as the social calendars of the churches were usually loaded with activities. Most Hungarians were dedicated to their particular church, and the well-attended church activities were considered family and community affairs. The eight clubhouses owned by Hungarian organizations provided meeting halls for the vast variety of community activities. The community’s social calendar included the following regular annual events (on the average): twelve grape harvest festivals, eleven New Year’s Eve dances, fourteen picnics, twelve plays, twenty banquets and over 100 Hungarian weddings.[6] In addition, lectures, forums, meetings (both civic and political), bazaars and card parties were weekly events held at individual clubhouses and church halls.

Six Hungarian-language newspapers served the community. The largest, Szabadság, reached a daily circulation of 40,612 in 1940.[7] By 1920, more than 300 Hungarian-owned businesses were thriving, and eighty-one Hungarian organizations were active in Cleveland.

Neighborhood dances and balls were weekly events and Hungarian bands were in great demand throughout the year. This was especially true in the years between the two World Wars, when the number of community events usually outnumbered the available number of Hungarian bands. One such orchestra was organized by Michael Veres, the son of immigrant parents. The orchestra became known as the Veres Huszárs, as they performed wearing Hungarian Huszár uniforms. Michael Veres and his Huszárs were commissioned to play at President McKinley’s funeral.[8]

It was not uncommon to witness a gypsy band travelling along Buckeye Road in a wagon, serenading all who cared to listen. Gypsy bands were part of nearly every community event and most major privately sponsored events. Characteristically, the Hungarian people have always demonstrated a great love of music and dancing and this love of music occupied several generations of gypsies in the service of the Cleveland Hungarian colony.

The Hungarian neighborhood was self-contained; children were born, raised and educated within the community. Intermarriage with outsiders was shunned, although in later years this became more lax. In 1928, fully three-fourths or 75.5 percent of Hungarian-born men in the United States married Hungarian-born women.[9] It may be assumed that in Cleveland this percentage was closer to ninety percent at this time.

The greatest degree of thrift was exercised. Rose and vegetable gardens were cultivated in every yard. Garbage could go uncollected for weeks because there was so little of it, nearly everything was used up or re-cycled in the home. Clothing was sewn at home, only the material was purchased. In the 1920s, many households kept chickens. The canning of fruits and vegetables was commonplace and even wines were prepared at home. Thrift was considered to be a special talent, and a degree of spartan-type living was a source of pride. Children usually devised and hand-crafted their own toys and playground equipment. They organized their own block teams and these neighborhood teams would challenge each other for the area championship.

Generally, automobiles were considered an unnecessary luxury and homes were modestly furnished. Above all, financial stability and savings were greatly valued. Everything was purchased with cash, going into debt in order to own an automobile seemed incomprehensible. In 1940 a supervisor of the Buckeye Relief Office estimated that only some 350 Hungarian families were on the total case load of 4,100.[10] Mrs. Elizabeth Mudri, organizer and first President of the Senior Citizens Coalition, said of the elderly on Buckeye in 1978: “You have a hard time convincing them that they are entitled to certain programs, certain benefits.”[11] This attitude was not only reflected in private ownership, but community ownership as well. The mortgages for the neighborhood churches and clubhouses were amortized usually within less than a decade and the community maintained these churches and facilities even during the darkest days of the depression.

Sunday was always a special day in the neighborhood, set aside for community events. In the morning hours, the streets were lined with families en route to church, everyone dressed in their Sunday best. The afternoon was reserved for socializing and visiting relatives. In the winter the older children would be allowed to patronize the local neighborhood movie house; some of these establishments ran only Hungarian films. Picnics occupied the majority of Sunday afternoons in the spring and summer. Community soccer teams would challenge each other at these outings. Because of the frequency of these picnics, Woodland Hills Park was virtually renamed the “Hungarian Park”.

Many of the folk customs and rich traditions of the villages in Hungary were transplanted to the Hungarian neighborhood and for several generations these customs endured in much the same way as practiced in Hungary. It may have seemed peculiar to an outsider that a community, situated in a large American industrial center, would continue to celebrate the wheat and grape harvests with numerous festivities; however, these customs were so entrenched in the memories and lives of these immigrants that it was impossible to imagine life without them, even in America.

The community calendar commenced with the New Year. Around this time there was always much merrymaking and singing at clubhouses, dances, balls, private parties and saloons. Usually, the church halls, as well as most of the clubhouses, held New Year’s Eve dances. All were filled to capacity. On New Year’s Day, gypsy bands could be seen strolling up and down the streets, anxious to serenade potential customers.

Before Lent, the “Bogo Temetés”, or funeral of the bass viola took place, ushering in the period of no music or dancing until after Easter. The occasion was always a favorite of Buckeye Hungarians. Men, women and children dress up as gypsies and reenact, in a comical way, the story of a gypsy caravan burying their bass viola, amidst much heart rendering sorrow and sobbing. It is interesting to note that this custom is not well-known in Hungary. It was adopted by the Buckeye neighborhood, probably from the gypsies who played in the Hungarian colony.

The maidens returned the favor by presenting the young men hand-painted Easter eggs. The entire community participated in this age old custom, from young boys to old grandmothers. Red Cross Pharmacy on East 89th Street and Buckeye and the St. Elizabeth’s Pharmacy (directly across the street from St. Elizabeth’s Church) had signs offering free rose water on these occasions.

Traditionally, on the first of May a decorated “May tree” would be presented by a young man to a maiden, as a sign of endearment. In the Hungarian neighborhood, a man would send a gypsy band to serenade his girlfriend or wife and the scene around Buckeye that day was one of gypsies carrying their instruments from house to house.

Hungarian weddings were held year-round, but the majority took place in the summertime. The village marriage ceremonies were elaborate, involving many time-honored traditions. Usually, the festivities would last for two to three days. They were communal affairs, with friends and relatives performing all the preparations.

In September and October the wheat and grape harvest festivals were held, commencing on Labor Day at St. Elizabeth’s Hall and continuing until October 31. On the average, twelve were sponsored by various community organizations annually.

On December 6th, the feast of St. Nicholas was commemorated. The children were instructed to put out their shined shoes before they went to bed so that St. Nicholas could fill them with candies, nuts and fruits. Well-behaved children were rewarded with the delicacies, whereas naughty children received a switch.

Christmas in the community was deeply spiritual, centering around the family. Christmas trees were decorated with homemade items, such as handicrafts, pastries, honey bread and candles. Gifts for the most part were also homemade and modest.

C. ALIENATION AND CONFLICT

Several community leaders were bestowed with the Hungarian Order of the Red Cross in recognition of their outstanding work in helping to alleviate the post-War sufferings in Hungary. Three of the recipients were: Msgr. Charles Boehm, who campaigned for the prisoner repatriation fund, Helen Horváth, who initiated a program aiding impoverished teachers and Rose Üto, for her efforts in providing food for malnourished children.

During the War, large-scale programs were instituted to “Americanize” the immigrant groups. These programs, promoting the abandonment of one’s own heritage, language and mannerisms, were intensified following the end of the War. Various individuals in the community worked in support of the concept with the result that a few “Americanization” newspapers and adult education programs came into existence. The sometimes ludicrous nature of the forced Americanization effort was demonstrated in one photograph of the congregation of St. Emeric Roman Catholic Church, wherein each of the some two thousand individuals photographed is holding a small American flag.

The Roman Catholic Church in the United States played a major role in the concerted effort to Americanize the immigrant groups. They were among the first to reduce and finally eliminate foreign language classes from the parochial elementary school curriculum. Some Bishops of the Cleveland Diocese made efforts to ensure that Hungarian priests would not serve the Hungarian parishes, believing that they were doing this for the ultimate “good” of the community.

The Hungarian community was affected by the Americanization program in several different ways. Because of the size and strength of the community, some segments became more determined to maintain the language and culture. Although Hungarian language instruction during regular school hours was discontinued at the Roman Catholic elementary schools, several churches of the Greek Catholic faith and various Protestant denominations initiated Hungarian classes after school and during the summer vacation. Generally, second generation children were perfectly bilingual and spoke Hungarian more correctly than their parents, whose formal education was usually limited.

The second generation was increasingly affected by the pressure to Americanize. Characteristic of this generation were the numerous cultural organizations which promoted Hungarian culture in the English language: such as the Hungarian Junior League, the Four Arts Club and the Hungarian Civic Club. Numerous Hungarians Anglicized their names, some did so because they wanted to enter a profession.

The second generation further realized that if they wanted to enter the mainstream of American life and attain positions of influence, they would have to wield power through Hungarian professional organizations. The Hungarian Businessmen’s and Tradesmen’s Club became an influential organization in the city, representing twenty-six lines of business with over 250 members reported in 1941.[14] The Magyar Club established a position for Hungarian professionals in the civic and political arena of Cleveland. Founded by lawyers and city politicians in 1924, the Magyar Club has become one of the most prestigious organizations in the community.

Underlying the campaign to Americanize was the concept that American culture is superior to all others and in this respect it was extremely detrimental to the self-image of Hungarians, particularly those of the second generation, who were made to feel ashamed of their heritage, mother tongue and parents’ background. In fact, the Americanization propaganda undermined and ridiculed the way they lived, the way they were raised and the idea of a Hungarian neighborhood. Although the program forced Hungarians to become part of the mainstream of American life at an accelerated pace, this was accomplished at a considerable cost in the loss of cultural contributions and ethnic identity.

The Labor Movement significantly affected the activities of the community during the 1920s and ’30s. Hungarian immigrants were likely victims of exploitation: they were handicapped by language barriers, used to abominable working conditions and were usually willing to take almost any kind of work. Some Hungarians, totally unaware of the labor conditions in this country, were brought to the coal mining regions of West Virginia and Virginia as strikebreakers. Much hatred and violence was directed against them because of this.

Organizations developed which sought to inform the Hungarian immigrant about labor conditions in America and to work for the improvement of those conditions. The Sándor Petofi Socialist Workers’ Society of Cleveland made possible the publication of the first Hungarian-language labor newspaper, The Amerikai Népszava (The American People’s Voice) in 1891.[15] The Népszava was transferred from New York to Cleveland in 1896, but because of incidents of violence and various strikes in that city, was forced to move back to New York within one year.

In 1912, the first Hungarian-language socialist daily, Elore (Forward) was established in Cleveland; the newspaper’s first editor was Louis Tarcai. This newspaper was published in Cleveland for only a few years. Tarcai founded another socialist newspaper, Az Ujság (The News) in 1920, which provided information about local neighborhood news, activities and services. Tarcai was also active in the organization and upkeep of the soup kitchens on Buckeye Road which were supported by local businessmen during the Depression.

Following the end of the First World War, considerable efforts were expended by the government to weaken the labor movement. Some fifty Hungarian leftist journalists and writers were imprisoned and threatened with deportation. Elore was discontinued in 1921; later that year Új Elore (New Forward) was founded to replace it. During the 1930s, Új Elore was transferred to Cleveland in order to “get closer to the industrial worker masses, in particular those employed in heavy industry.”[16]

The Hungarian-language labor press served an important function: it informed workers about what the norms were as far as pay, working hours and conditions and agitated to change these factors for the betterment of the working class. One example of the many abuses prevalent in industry was child labor.

There were few children playing in the streets during the 1920s and 1930s in the Hungarian neighborhood. All efforts went towards earning money, often at the expense of schooling. Child funerals were frequent, these deaths were caused by normal diseases as well as industrial illnesses. For example, girls who worked in the cigar factories often contracted tuberculosis by the time they reached the age of eighteen.

One Hungarian-language newspaper wrote in 1892: “Many of our countrymen work in the plough factory… The whetstone has already killed two of them. We warn our countrymen in time-although they know it themselves, without the physicians telling them-that the dust created by the grinding of the plough steel on the whetstone settles in the lungs of the workmen and causes consumption in a few years.”[17]

Új Elore published countless short stories and poems which conveyed the many hardships endured by Hungarian immigrant laborers. The stories were written about fictional characters, however, they were based on actual incidents related by the immigrants themselves. There were short stories published about the mining towns of Pennsylvania and West Virginia, where many of the Hungarians found initial employment. The writings conveyed the degradation of living in shabbily constructed company shanty towns, of having to work underground and breathing the soot and smoke of the mine. There were many other stories as well: of children who were orphaned due to industrial accidents and of young girls who worked in sweatshops under stifling, unhealthy working conditions for meager wages.

Despite the fact that the underlying theme of many of these writings was that capitalism exploits the working class, the stories realistically described many of the most critical social problems affecting the working class in America during the 1920s and ’30s.

Various segments of the Hungarian labor movement joined larger American labor organizations, such as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and the American Labor Alliance. Hungarian leftist organizations provided their members with sick benefits through the Workers’ Sick Benefit and Self-Education Federation, which had several chapters in Cleveland. The Workingman’s Home on Buckeye Road served as a meeting place for many groups, including: Hungarians with leftist views, members of the community alienated from the churches and unemployed and/or discontented workers. Leftist groups formed their own cultural organizations; during the 1930s, Hungarian workers’ choirs were active on both the west side and east side of Cleveland.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the community was characterized by strong divisions between the left and the right. The left encountered many confrontations, not only with various segments of the community but with local authorities as well. One example of this is a widely accepted rumor that Buckeye Road was originally known as Moreland Road, its name was allegedly changed to Buckeye around 1920 after a Cleveland policeman was knifed to death there by a group of Hungarian communist demonstrators. According to one source: “When the killing received national notoriety, the residents, feeling stigmatized, changed the name of their main street.”[18]

The popularity of the Hungarian labor movement diminished with the advent of the Second World War and the improvement of economic conditions.

Moreover, after the Second World War, many Hungarian-American leftist leaders returned to Hungary.

During the Depression, one commonly used expression in the neighborhood, which expressed the desperate plight of many of the residents, was: “For fifty cents, we would leap over the rooftop of any building.”[19] Nearly fifty percent of Hungarian male workers in Cleveland were unemployed, many families lost their homes and thousands in the community watched their savings slowly disintegrate through the long years of economic hardship. Since many of these immigrants were aliens (not U.S. citizens) and property owners of record, they were ineligible for public assistance. There were no social insurance programs in existence at this time such as social security or unemployment compensation. As a result, the majority of unemployed Hungarians in the community were left without any means of support. Even if found eligible for public assistance, psychologically, it was humiliating for the immigrants to request government aid. In many instances, where men could not find work, women became the bread winners as domestic servants earning $2 a day for house cleaning and completing laundry.

The economic situation put a great strain on everyone; however, it has been often said that nothing brings people together more than hard times and nowhere else was there more evidence of this than in the Buckeye Road Hungarian neighborhood. Families relied on church groups, sick benefit societies and each other for assistance. New organizations were founded in response to the changing needs. The Cleveland Hungarian Ladies Charity Committee was established to assist in the phenomenal task of feeding the hungry, as the majority of the people in the neighborhood were job less and penniless in those days. Daily, the women went to grocery stores, meat markets and bakeries requesting foodstuffs. Whatever they received from the merchants was then prepared and served at the soup kitchens. In spite of the fact that the lineups were tremendous, everyone was welcome. The work involved was overwhelming, yet these kitchens were upheld even during the darkest days of the Depression.

The Old Settlers Association, which later became one of the largest Hungarian organizations in the community, was established during the Depression. It was founded in response to the growing number of Hungarians, who because of economic difficulties or affiliations with the labor movement, lost contact with their churches and could therefore not secure a church burial. For a nominal membership fee, the Old Settlers Association assured all members of a decent burial in addition to providing pall bearers.

The Small Home Owners’ Association was founded in 1930 by a group of homeowners to prevent the eviction of friends and neighbors in the event of foreclosures. The efforts of these homeowners were futile against the injustices of these hard times, but they could not stand by idly as their homes were being confiscated. Some of the demonstrations turned into virtual riots as violent confrontations took place between the police and the Hungarian and Slovak homeowners.

During these hard times, people spent their free time organizing community activities, such as: dances, socials and plays. The production of community plays involved dozens of people of all ages, nevertheless, the time, energy and even costumes and props were willingly donated. The admission to these plays was very cheap so that many could attend; the aim was to entertain and have fun, not to make a profit. Through this upsurge in amateur performances in the dramatic arts, the second generation gained stage experience, self-confidence and a real appreciation of Hungarian Literature.

People shared what little they had, the 1930s was a decade of great solidarity in the community. One Buckeye resident recalled how two or three families would get together and share a simple meal of cabbage dumplings, the taste of those dumplings was wonderful because: “…In those days we were hungry and what little we had tasted so good.”[20]

D. HUNGARIANS IN POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT

Hungarians in Cleveland have played a substantial role in local and regional government. The Buckeye Road Hungarian community, which encompassed Ward 29 and Ward 16, provided an excellent voting bloc. It was generally said that, “If your name isn’t Hungarian, forget about running for election in 29 or 16.” The first Hungarian Councilman elected from Ward 29 was Louis Petrash; he was elected in 1921. Petrash set the trend, soon other talented lawyers and professionals realized that politics could be actively pursued by anyone, not only established Clevelanders. Furthermore, they realized that it was their responsibility to provide effective leadership and representation for the large Hungarian constituency in Cleveland.

For nearly forty-five years Ward 29 was represented by Hungarian representatives to City Council. In Ward 16, Hungarian representation spanned thirty years, from 1939 until 1971. Approximately twenty-six Hungarian-Americans from the Buckeye Community were elected or appointed to various offices in the city, county and state levels of government (See Appendix). The Hungarians who immigrated prior to the First World War and their children participated most actively in local politics and government. Hungarians immigrating after the Second World War and 1956 were far less politically conscious when compared to these “old-timers”. The Buckeye Hungarians voted overwhelmingly Democrat, as a direct result of the Depression and the Roosevelt Presidency.

Several generations of assimilation were not required for Hungarians to become active in local politics. Immigrants were frequently elected or appointed to high ranking government positions. Joseph Fodor (Investigating Attorney, Public Utilities Commission of Ohio), Frigyes Gonda (Ohio State Parole Board Supervisor), George Matowitz (Cleveland Chief of Police), and Hugo Varga (Director, Department of Parks and Public Property), along with many others, were all born in Hungary. Imre B. Freed, an immigrant from the County of Bereg, was appointed United States District Attorney under the Roosevelt Administration. Freed is the only Hungarian immigrant from Cleveland known to have served in the federal government. Usually these Hungarians immigrated as children with their parents and completed their education in this country. It is interesting to note the comparatively large numbers of professionals, especially lawyers, who emerged as part of this generation. Their immigrant status was an added hindrance to the difficult upward climb, but for the majority, the disadvantages only made them more determined to achieve their goal.

From 1931 to 1974, there were usually two and oftentimes three Hungarian judges out of nine serving on the bench of the Municipal Court of Cleveland. These judges devoted decades of service to the citizens of the city, they were the pride of the community: Julius M. Kovachy (thirty years), Louis Petrash (thirty-two years), Joseph Stearns (twenty-one years) and Blanche Krupansky (seven years). Andrew M. Kovachy and Blanche Krupansky also served as judges of the Common Pleas Court of Cuyahoga County.

One of the most influential politicians in the history of city government was Jack P. Russell, the son of immigrant parents from Abauj County, Hungary. Russell was born in Cleveland on lower Buckeye Road. As a young man, he changed his name from Pal Ruschak to Jack P. Russell.[21] In 1943, Jack Russell was first elected to Cleveland City Council as councilman from Ward 16, which encompassed lower Buckeye Road. Russell retained this Council seat for twenty-eight years, or fourteen terms. Within a few years, he was chosen by his fellow Democrats to serve as their majority leader, a capacity in which he served for eight years.

In 1957, Jack Russell was elected President of Cleveland City Council, a position of considerable power and influence. Russell held this position for eleven years, during which time his leadership abilities were repeatedly tried and proven. Eric Sevareid produced a half-hour special report for national television about the life and activities of Jack Russell. The program portrayed him as the ideal local politician. Russell even taught a course on practical politics at Harvard University.

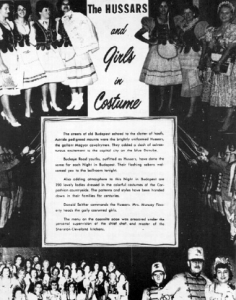

Jack P. Russell initiated and organized the annual “Night in Budapest” social galas, which became one of the most exciting events in the City of Cleveland. The first one was held in 1957 at Bethlen Hall on Buckeye Road. Within a few years, however, because of the overwhelming crowds attending, the event was moved downtown to the Sheraton Cleveland Hotel.

The “Nights in Budapest” were famous for the Hungarian atmosphere. American audiences could enjoy excellent Hungarian cuisine, top gypsy orchestras and bands and the finest entertainers, such as: opera stars, pianists and comedians. The guests were welcomed by a lineup of young Hungarian men, outfitted as Hussars. Their sabers were outstretched and raised, forming an archway for the incoming guests. Two hundred women from the community, dressed in stylized Hungarian costumes, were the hostesses to the average attendance of one thousand. The outstanding attractions were the local and national celebrities; each year several Hollywood actors and movie stars attended.

Hollywood producer, Joe Pasternak, who immigrated from Hungary as a young man, sponsored the exciting array of celebrities. As National Chairman, Pasternak attended the annual gala event, bringing with him different actors and actresses each year, such as: Zsa Zsa Gabor, Edie Adams, Kurt Kasznar, Mitzi Gaynor, Bill Dana, Jimmy Durante and Kaye Stevens. Annually, prominent individuals on the local and national level were honored for distinguished service to the Hungarian-American community. In 1970, after fourteen years of organizing the famous “Nights in Budapest”, Jack Russell retired and the prestigious galas were discontinued.

- Interview with Dr. István Eszterhás, 12 February 1978. ↵

- Interview with Mrs. Bertha Ludescher, 16 February 1978. ↵

- John Körösfoy, op. cit., p. 16. ↵

- Karl B. Bonutti and George J. Prpic, Selected Ethnic Communities of Cleveland: a Socio-Economic Study (Cleveland: (The Cleveland Urban Observatory). , 1974), p. 31. ↵

- U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of Census, 14th Census, 1920, vol. 1 & 2 (Washington, D.C., 1922). ↵

- (Karl B. Bonutti and George J. Prpic, op. cit., p. 44. ↵

- Lengyel, Americans from Hungary (Philadelphia/New York: (J.B. Lippincott Co.). , 1949), p. 203. ↵

- Interview conducted by Theodore Andrica with Michael Veres, September 1937, Andrica collection, Cleveland State University. ↵

- Lengyel, op. cit., p. 226. ↵

- William Miller, "Howdy Neighbor," The Cleveland Press, 10 February 1940, p. 9. ↵

- Interview with Mrs. Elizabeth Mudri, 16 February 1978. ↵

- Interview with Mrs. Margaret Kovell, 10 July 1979. ↵

- Huldah F. Cook, op. cit., p. 14. ↵

- Emlékkönyv A Clevelandi Magyar Kereskedok és Iparosok Körének 25 Éves Jubileuma Alkalmábol 1923-1948 (Cleveland: (Hungarian Businessmen's & Tradesmen's Club). , 1948), Theodore Andrica collection. ↵

- Jozsef Kovács, A Szocialista Magyar Irodalom Dokumentumai Az Amerikai Magyar Sajtóban 1920-1945 (Budapest: (Akademiai Kiadó). , 1977), p. 20. ↵

- Ibid., p. 37. ↵

- According to a manuscript compiled by Dr. John Palasics et al. , this excerpt is from a book entitled, People of Cleveland, p. 113. ↵

- Joseph Eszterhás, "Buckeye Road: Neighborhood of Fear," Cleveland Plain Dealer, 18 January 1971, p. 1. ↵

- Interview with Dr. István Eszterhás, 12 February 1978. ↵

- Interview with Mrs. Elizabeth Mudri, 16 February 1978. ↵

- Interview with Jack P. Russell, 14 February 1978. ↵