Section II: Hungarians in America

The Civil War Era (1851-1870)

A. Kossuth in America

The Hungarian War of Independence of 1848 was dramatic and courageous. Through asserting her independence, Hungary gained the respect and admiration of many nations of the world. The United States, in particular, observed the developments with anticipation. The American people felt that Hungary’s struggle with Austria was similar to the one they had experienced with England in 1776. Unable to send military aid, the United States sent support and encouragement. In June of 1849, President Zachary Taylor appointed Ambrose Dudley Mann, a special confidential agent, to convey the United States’ recognition of the Hungarian Revolutionary Government.

After Hungary’s defeat by the combined forces of Austria and Russia, the United States again showed its sympathy for the Hungarian cause. In 1851, President Fillmore, empowered by the Senate and the House of Representatives, sent an American warship to Turkey to bring Louis Kossuth and his followers to the United States. The U.S.S. Mississippi brought the exiled governor of Hungary along with the other Hungarian emigrés from Turkey to England, where Kossuth made a stopover, sending the rest of the emigrés on to America. Kossuth’s visit in England was brief, he soon departed for the United States aboard the Humboldt, and arrived in New York on December 4, 1851.

Kossuth felt that in America, popular sentiment would be with the Hungarian cause. He came with the intention of gaining support, both financial and political, for a renewed effort to liberate Hungary from Austria. Kossuth’s efforts were twofold: to collect money for munitions and arms and to obtain support and acceptance of his famous “intervention for non-intervention principle.”

What he aspired to accomplish was to induce the American nation to declare through Congress, that, in case a foreign government attempted to prevent a nation by force of arms from exercising its right of self-determination (as was done by Russia in the struggle of Hungary against Austria), the American Government would intervene to prevent or stop such unlawful intervention.[1]

Popular sentiment in the United States was with Kossuth. He was given a hero’s welcome and everywhere he went large crowds gathered to hear the “Washington of Hungary.” Kossuth spoke English well; he learned it, while imprisoned by the Austrians, from an English translation of the Bible and the works of Shakespeare. As a result of his training, he often surprised his audiences with a remarkable use of archaic English words and grammar.

In New York, it was estimated that over 200,000 people crowded into the streets to welcome the governor of Hungary:

So dense was the multitude in Broadway, and so great was the pressure, that thousands upon thousands were forced out of the procession into the side-streets, and parallel streams of human beings rushed up… in order to get a little ahead, so as to obtain a sight of the procession. For the entire route of the procession through the Bowery, the people filled every available spot long before the procession started. All along the line of march, and indeed throughout the city generally, business was suspended, and the whole demonstration was one of the greatest, most important, and most enthusiastic ever given.[2]

During his stay in New York City, Kossuth was invited to speak at such places as the Irving House, Tammany Hall and Plymouth Church. He addressed numerous groups, including the Press Banquet, the New York State Militia and the Ladies of New York.

In Washington, Kossuth was invited to the White House, the House of Representatives and the Senate. He was requested to address the House of Representatives, an honor bestowed previously only on General Lafayette in 1824.

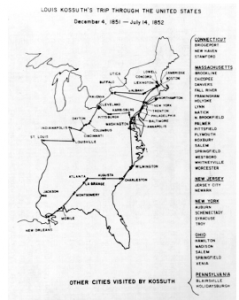

Kossuth visited sixteen states and countless cities and towns in the United States (see map). Everywhere he went, throngs of people gathered to see and hear the “Champion of Liberty.” He addressed the state legislatures of Maryland, Ohio, Indiana and Massachusetts. Even in the South, where Kossuth was mistrusted by southern slave holders for his speeches on human rights and liberty, he was received and applauded by thousands.

Kossuth inspired many American and English poets with his campaign for human rights and devotion to the cause of freedom. Those who wrote about him included poets such as Arnold, Elizabeth Browning, Garrison, Lowell, Massey, Whittier and such writers as Bryant and Longfellow. In Concord, Massachusetts, Ralph Waldo Emerson greeted Kossuth:

We only see in you the angel of freedom; crossing sea and land; crossing prairies; nationalities, private interests and self-esteems; dividing populations, where you go, and drawing to your part only the good. We are afraid you are growing popular, sir; you may be called to the dangers of prosperity. But hitherto you have had, in all countries and in all parties, only the men of heart.[3]

Over 250 poems were written about Kossuth by amateur poets, which were printed in local newspapers throughout the United States during his visit. In Boston, slogans such as “Washington and Kossuth-the Occident and the Orient” and “Washington, the Friend of Liberty; Kossuth, the Foe of Despotism” were written on banners and displayed at rallies, banquets and meetings held in his honor.[4] Hundreds of editorials and pamphlets were written about him, and Kossuth cards, Kossuth satin badges and Kossuth prints were sold wherever he went. His popularity grew to such extent that the production and selling of Kossuth souvenirs became quite profitable. Enterprising businessmen used Kossuth’s name in their advertisements, one example of many was the advertisement of a New York photographer:

KOSSUTH TAKEN-what the Austrians could not do, Root & Co., No. 363 Broadway, have done, for on Friday, they succeeded in capturing the illustrious hero in his carriage on Staten Island.[5]

The “Kossuth Craze” which was the term coined to describe his overwhelming popularity, was evident everywhere he traveled. The soft hat worn by Louis Kossuth became the latest fashion. Four towns, one county and six streets were named after the exiled Hungarian governor (all are still in use today). A child born in Cleveland at the time of Kossuth’s visit was named E.K. Willcox, the E.K. standing for Éljen Kossuth (Long Live Kossuth). Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote in his diary on December 19, 1851:

Everyday brings a new speech of Kossuth-stirring and eloquent. All New York is in a blaze with his words-quite mad. Wonderful power of oratory and the pleading of sincere heart in the cause of human rights! But why need people go clean daft?[6]

Louis Kossuth sailed back to England on July 14, 1852. In the United States, he gained nationwide support for the Hungarian cause and impressed upon the minds of Americans the need for solidarity among the freedom-loving nations of the world. The ideas espoused by Kossuth were far in advance of his time. Through his exceptional skills as a writer and orator, he demonstrated what one man could achieve in the interests of his homeland; “…to shake the solid mind of a whole nation, to agitate the mighty heart of a vast continent, and even to effect and modify the public opinion and the public affairs of the world.”[7]

B. The Emigrés

The Hungarians who came to the United States in the 1850s were part of what historians refer to as the “Kossuth Emigration.” The majority had little choice but to emigrate, because of their involvement in the Hungarian War of Independence. Generally, the emigres were well-educated and members of the middle and upper classes of Hungary. Many were politicians, educators, diplomats and high-ranking army officers who served meritoriously in the War of 1848.

They proved to be valuable citizens of the United States. Most accepted their adopted homeland as permanent until such time when Hungary would be free of Austrian rule. During the Civil War, at a time when the North was in desperate need of trained military officers, 800 Hungarian emigrés (of the 4,000 who were living in the United States) volunteered their expertise to fight for the Union cause.

László Újházy was among the first to arrive with his family and the first Hungarian of the emigrés to become a naturalized citizen of the United States. Receptions were held in his honor in New York, Washington and Philadelphia. Újházy secured welcome for many emigrés who followed through his sincerity and goodwill. László Újházy founded the first Hungarian settlement in the United States at New Buda, Iowa.

The emigrés gained recognition for their struggle during the War of Independence and for the most part, they found favorable positions and excelled in American society. Nicholas Fejérvári became a successful real estate broker in Davenport, Iowa. He bequeathed the Fejérvári Home for the Aged and a large garden to the city of Davenport, which was later named Fejérvári Park in his honor. Michael Heilprin, a former writer in Hungary, became a writer and editor for Appleton’s New American Encyclopedia. Later, he obtained a position as a columnist for the Nation in Washington. Heilprin also took active part in the “New Yorki Magyar Egylet” (The New York Hungarian Association). Several Hungarian emigrés became professors at American universities. On numerous occasions, Hungarian officers were appointed United States consuls to foreign countries, in recognition of their meritorious service during the Civil War. Hungarian emigrés served as American consuls to Japan and China, Argentina and Paraguay, British Guinea, Hungary, Rumania, Italy and Mexico.

The Hungarian emigrés settled in New York City (with the largest Hungarian population), New Orleans (Louisiana), St. Louis (Missouri), and a small group in Davenport (Iowa). The first Hungarian society, The Central Hungarian Society, was formed in New York City in September 1849. Its purpose was to aid Hungary by securing goodwill in America. In 1850 a Hungarian club was founded in Boston by George L. Stearns. The first Hungarian restaurant named “To the Three Hungarians” was opened in New York by Mátyás Nyújtó in 1851. Charles Kornis published the first Hungarian newspaper, Számuzottek Lapja (Journal of Hungarian Exiles) in 1853. In 1865 the first significant Hungarian immigrant institution, “New Yorki Magyar Egylet” (The New York Hungarian Association) was established.

László Újházy hoped to establish a Hungarian settlement in the United States. Along with three other emigrés, Újházy bought settlers rights’ in the new State of Iowa-they named the settlement in Decatur County “New Buda.” Újházy was named postmaster of the settlement and eventually more Hungarians followed.

These Hungarian emigrés were of the opinion that their strength depended on unity of thought and action. If any change occurred in the political situation in Hungary, a group of Hungarians living together could act quickly. Also, they wished to preserve the social and domestic aspects of life in Hungary. The community became much like a Hungarian village where Hungarian traditions and customs were maintained.

The settlement consisted of no more than one hundred immigrants at any time. These scholars, statesmen, soldiers and gentlemen farmers were not accustomed to the rugged life prairie farming afforded. One immigrant, Ferenc Varga, recounts his first meeting with László Újházy in New Buda:

How could I describe that meeting? The elderly Újházy, in a red flannel shirt and an old hat was plastering the chimney. I was dumbfounded. I saw before me his castle near Buda and thought of the many times I had heard him speak at the Sáros County Hall. Could it be possible that in the space of one year this would be the fate of the well-renowned Patriot, the Lord Lieutenant of the County of Sáros?[8]

The success of New Buda was short-lived. The rugged life and harsh climate eventually discouraged many of the Hungarian settlers. László Újházy left New Buda grief-stricken when his wife died—he journeyed to Texas. Years later, President Lincoln appointed him United States consul to Italy.

An additional cause of the eventual disintegration of the Hungarian settlement was the Civil War. Many of the emigrés were soldiers by profession; they enlisted and served in large numbers in the Union Army. New Buda later became the site of Davis City, Iowa.

Joseph Pulitzer, the founder of the famous Pulitzer Prizes, was born in Makó, Hungary on April 10, 1847. He was the son of a prosperous grain merchant. When his father died, his mother remarried and young Joseph’s life was made miserable by his new stepfather. At the age of seventeen, Joseph left Hungary and attempted to join the armies of Austria, France and Britain, but was rejected because of his poor eyesight and weak physical stature. In Hamburg, Germany an agent for the Union Army recruited Joseph and placed him on the first ship bound for the United States. Arriving in New York, Joseph enlisted in the First New York Cavalry Regiment. He served under General P.H. Sheridan and General George Armstrong Custer and was mustered out of service in July of 1865, at the age of eighteen. In that same year he headed west for St. Louis, where he arrived penniless.

In St. Louis he became a reporter for a German-language newspaper, Westliche-Post. In a short while he obtained his American citizenship. In December of 1869, at the age of twenty-two, Joseph was elected to the lower house of the Missouri State Legislature. Here he led a successful campaign to reform the corrupt county government of St. Louis.

Pulitzer then became a newspaper proprietor. He bought the run down Post for its Associated Press franchise, merged it with the Dispatch as the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, creating one of the strongest independent newspapers in the country. By 1880 Pulitzer became its sole owner. Leaving the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in charge of a competent manager, he moved his family to New York where he bought The World. After only two years The World surpassed the circulations of the mighty Times, Tribune, Herald and Sun. By 1886 the annual earnings of The World were more than $500,000. William R. Hearst’s purchase of the New York Journal brought The World a powerful competitor, but Pulitzer met the challenge by reducing the price of his newspaper from three cents to two. In 1887 he created an evening edition, The New York Evening World. To The World, as to the Post-Dispatch, Pulitzer gave a tone of aggressive editorial independence. His editorials were sympathetic to labor and supported the cause of striking steel workers in Homestead, Pennsylvania in 1892.

During his lifetime, Pulitzer gave liberally. In 1903 he founded the School of Journalism at Columbia University, which opened in 1912. More important was the endowment of the Pulitzer Prizes, awarded annually “for the encouragement of public service, public morals, American literature and the advancement of education.” The Pulitzer Prizes recognize outstanding literature, drama, music and newspaper work and are considered “among the most coveted distinctions of writers and artists all over the United States.”

Pulitzer returned to visit Hungary on several occasions. In 1886 when Mihály Munkácsy, one of the greatest Hungarian painters, visited the United States, Pulitzer was there to present the welcoming address.

As he grew older, Joseph Pulitzer’s steadily worsening eyesight compelled him to live a secluded life. He died in October 1911 in Charleston, South Carolina. Joseph Pulitzer wrote the following statement when his blindness prevented him from continuing actual management of the paper. It still appears today in every copy of the Post-Dispatch in the upper left-hand corner of the editorial page:

THE POST-DISPATCH PLATFORM

I know that my retirement will make no difference in its cardinal principles; that it will always fight for progress and reform, never tolerate injustice or corruption, always fight demagogues of all parties, never belong to any party, always oppose privileged classes and public plunderers, never lack sympathy with the poor, always remain devoted to the public welfare; never be satisfied with merely printing news; always be drastically independent; never be afraid to attack wrong, whether by predatory plutocracy or predatory poverty.

C. Lincoln’s Hungarian Heroes

Of approximately 4,000 Hungarian immigrants who were in the United States at the time of the Civil War, 800 served in the Union Army, or twenty percent. “This degree of participation exceeds that of any other ethnic group in America.”[9]

There were an estimated 130 officers of the 800 Hungarians in the Union Army. Among them there were two major generals, five brigadier generals, fifteen colonels, two lieutenant colonels, fourteen majors, fifteen captains and several subalterns and surgeons.[10] In the Confederate Army there is record of less than eight Hungarians, of these only one officer by the name of B. Estván, who served as a cavalry colonel. Estván left the Confederate Army after a short time.

The majority of these emigrés were trained military officers who served meritoriously in the Hungarian War of Independence in 1848. The Union was in desperate need of trained military men and these emigrés volunteered their experience and expertise at a time when the “United” States were endangered. They fought with distinction and many were decorated. Major General Julius Stahel-Szamwald, well-known and trusted by President Lincoln, was the first Hungarian to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor for bravery. Major Charles Zágonyi led the famous “Charge of Springfield” which won the state of Missouri for the Union. Before the first cannon shots were fired at Fort Sumter, Colonel Géza Mihalótzy organized Lincoln’s Riflemen, one of the first company of immigrants.

Camps named after Hungarian officers distinguished in the Civil War were: Camp Asbóth, Camp Rombauer, Camp Utassy and Camp Zágonyi. Fort Mihalotzy, located in Chattanooga, Tennessee was named after Colonel Géza Mihalótzy, who was killed in an ambush nearby.

Many Hungarians were decorated and promoted to higher rank during the war. Many gave their lives for the Union cause. In a letter dated March 15, 1939, written for the commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Battle of Piedmont, Virginia, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt pays tribute to these Hungarians and commends their “valiant service to the cause of the Union.”

The majority of the Hungarians served under the Union flag for several reasons. During the Hungarian War of Independence in 1848, these men fought for the liberalization of Hungary. They left their homeland because they could no longer live under the oppressive and tyrannical rule of the Austrians. Rather than surrender their advanced social and political ideas, they chose to live in exile. Among the reforms they achieved in Hungary was the freeing of the serfs. How could they then, living in a country whose constitution assured freedom and democracy, fight for the retention of slavery? Naturally, they sided with the abolitionists and fought for the Union.

Hungarians made no secret of their strong anti-slavery sentiments, sometimes even at the risk of losing their positions. Ignace Hainer, a settler of New Buda, Iowa, became a professor of modern languages at the University of Columbia in Missouri. He held this position for four years, after which time he lost his job along with others because of his belief in the abolition of slavery. Anthony Vallas, who eventually became president of the New Orleans Academy of Sciences, was dismissed as professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at the Seminary of Learning of the State of Louisiana (Louisiana State University) because his sympathies were with the Union.

Lieutenant Alexander Jekelfalussy, commander of the 24th Illinois Regiment, received orders to capture and surrender all fugitive slaves hiding in Union regiment camps. Jekelfalussy promptly submitted resignation of his commission to his commanding officer with the explanation that he cannot, in good conscience, follow such an order.

There were several Hungarian officers who organized and commanded the colored regiments of the Union Army. Among them were Peter Dobozy, organizer of the 4th Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment and Lieutenant Zimandy of the 4th Colored Infantry Regiment.

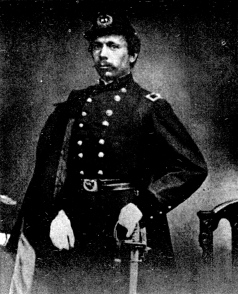

Julius Stahel-Szamwald immigrated to the United States in 1859 and joined the Union Army in the first year of the Civil War. Stahel-Szamwald organized and became the first lieutenant colonel of the 8th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment. In recognition of his meritorious service in the Battle of Cross Keyes, Virginia, he was appointed brigadier general and shortly thereafter, major general.

Stahel-Szamwald’s leadership and bravery in the Battle of Piedmont, West Virginia earned him the Congressional Medal of Honor. He was seriously wounded in the battle and left his troops only long enough to receive first aid, returning without delay to continue leading and advancing his troops. The battle was crucial because it decided the fate of the Shenandoah Valley which was the gateway for the Confederate Army to Maryland, Pennsylvania and the Capital itself.

President Lincoln, who was said to have had “unbounded confidence” in Stahel-Szamwald, personally requested the major general to command the cavalry protecting the Capital. Szamwald also headed the Honor Guard, made up of high-ranking officers of the Union Army, which escorted President Lincoln to Gettysburg.

After the Civil War ended, Stahel-Szamwald continued in the service of his adopted homeland as American consul to Japan and China, a position he held for more than eleven years. He died in 1912 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery with all the honors rendered an American military hero.

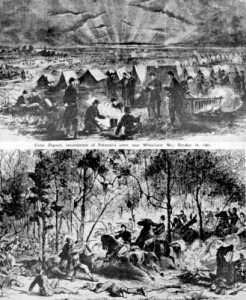

Major Charles Zágonyi became well-known in the United States when he led a cavalry charge of 160 Union soldiers against 2,000 Confederate soldiers holding the town of Springfield, Missouri. As a result of the victory, the Confederate soldiers retreated from Springfield and the state of Missouri (until then claimed by both sides) became part of the Union.

Charles Zágonyi was born in Szatmár in 1826. He served in the War of Independence under General Bem. Following the defeat he immigrated to England and then to the United States in 1851. Upon the outbreak of the Civil War, he joined with General Fremont in Missouri who gave Zágonyi permission to organize and command a body guard cavalry unit to be known as Fremont’s Guard. Zágonyi immediately set to work, personally selecting the horses and designing the uniforms to be used by the guard.

In the autumn of 1861, General Fremont, under the mistaken impression that the enemy numbered 300, gave permission for the newly-organized cavalry unit led by Zágonyi to attack the Confederate Army holding Springfield. Before the attack could occur, Fremont received reports of the Confederate Army’s actual strength, which was close to 2,000 men. He immediately withdrew permission to attack, but Zágonyi persuaded the general to allow the guard to proceed despite the reports.

Before the daring charge began, Zágonyi called his soldiers together and told them that any man wishing to turn back had his permission to do so Captain John T. Foley wrote: “not a man flinched,” after hearing Zágonyi’s proposal.[11] The famous Springfield Charge also known as Zágonyi’s Death-Ride, took place on October 25, 1861. The guard, fighting overwhelming odds, succeeded in recapturing Springfield and claiming the state of Missouri for the Union.

The guard lost sixteen men in the charge and the Confederates reported 116 men dead.

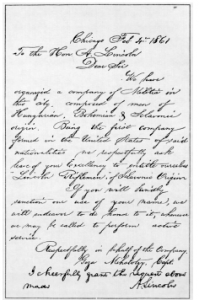

Géza Milahótzy served as a captain the Hungarian War of Independence in 1848. In the early part of the Civil War he organized a company of Hungarians, Czechs and Germans in Chicago and requested permission in a letter to the president to name the company Lincoln’s Riflemen. President Lincoln’s approval along with his signature was written on the same letter of request.

The historical document read as follows:

Chicago Feb. 4, 1861

To the Hon. A. Lincoln

Dear Sir:

We have organized a company of Militia in this City, composed of men of Hungarian, Bohemian & Slavonic origin. Being the first company formed in the United States of said nationalities we respectfully ask leave of your Excellency to entitle ourselves “Lincoln Riflemen,” of Slavonic origin.

If you will kindly sanction our use of your name, we will endeavor to do honor to it, whenever we may be called to perform active service.

Respectfully on behalf of the Company,

Géza Mihalótzy, Captain

I cheerfully grant the request above made. A. Lincoln

The newly organized Lincoln’s Riflemen were merged with the 24th Illinois Volunteer Regiment and Mihalotzy was named colonel of the regiment. The unified regiment fought with distinction in numerous battles of the war. Colonel Mihalotzy was seriously injured by a bullet on February 24, 1864. Shortly thereafter on March 11, he died of his injury in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where he was buried in the National Cemetery. Fort Mihalótzy, located on Cameron Hill near Chattanooga was named in memory of the Hungarian officer who gave his life for the Union.

Alexander Asboth served as an engineer in the War of 1848 and afterwards came to the United States with Kossuth on the Mississippi. He worked as a mining engineer in the western United States and later on the New York Planning Commission, where he was known to have had a major role in the planning of Central Park.

At the outbreak of the Civil War he enlisted and served on the staff of General Fremont. He took part in several battles in the states of Missouri and Arkansas. In the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, Alexander Asbóth fought with exceptional merit and in recognition was appointed brigadier general by the Congress of the United States. He served in this capacity on the staffs of Generals Fremont, Hunter and Curtis.

Asboth was seriously injured in the Battle of Marianna, Florida where bullets inflicted wounds on his arm and face. The bullet which was lodged in the right side of his face was especially critical as it could not be removed, although this was attempted by surgeons on numerous occasions. During the rest of his life the wound caused him much discomfort and pain and it eventually caused his death.

At the end of the Civil War, in recognition of his valuable service, President Grant appointed Asboth United States minister to Argentina and Paraguay. In South America, despite his painful facial wound, he performed his duties as minister with distinction. Asboth died two years later on January 21, 1868 at the age of fifty-seven, and was buried in an English cemetery in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Major General Alexander Asboth was remembered as “a tall, spare man, a splendid soldier, and an excellent commander, who coupled military discipline with humane treatment.”

A native of Arad, Frederick Knefler fought in the Hungarian War of Independence as a boy of fifteen. The family’s involvement in the revolution forced them to flee when it ended in defeat. They immigrated to the United States in 1850, where Frederick Knefler learned the trade of carpentry, while in the meantime studying law.

Following the outbreak of the Civil War, Knefler enlisted in the 11th Indiana Volunteer Regiment, and shortly afterwards became a captain. He was appointed adjutant to General Lew Wallace, the famous author of the biblical drama Ben Hur. Knefler was colonel in the 79th Indiana Volunteer Regiment until the end of the war, when, in recognition of his valuable service, he was appointed brigadier general. His leadership played a decisive role in the Battle of Missionary Ridge as well as in the Battles of Nashville, Chattanooga and Franklin.

Brigadier General Frederick Knefler was known for his well-disciplined troops and his genuine concern for his men. He consistently won the loyalty and admiration of his soldiers. Following the war, President Hayes appointed Knefler chief of the pension office, a position he held for eight years. The last years of his life were spent in efforts to build memorials for soldiers and sailors who fought and died in the Civil War.

Knefler died in 1901 in Indianapolis at the age of sixty-seven. He was hailed by the city as one of the most outstanding citizens of the community. The Indianapolis Journal wrote:

The last years of his life were devoted to the completion of the soldiers’ and sailors’ monument…. He planned and worked after most would have given up…. No truer American ceased to live, no better citizen in all the duties of citizenship was left in the city when the feeble flame of that manly spirit flickered out.[12]

- Eugene Pivány, op. cit. , p. 45. ↵

- Phineas C. Headley, The Life of Louis Kossuth (Auburn, England: (Derby & Miller). , 1852), p. 258. ↵

- Robert Carter, Kossuth in New England (Boston: (J.P. Jewett & Co.). , 1852), p. 223. ↵

- John Komlos, Louis Kossuth in America, 1851-1852 (Buffalo: (East European Institute). , 1973), p. 128. ↵

- The New York Daily Tribune, 11 December 1851. ↵

- Samuel Longfellow, ed., The Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow with Extracts from his Journals and Correspondence, vol. II (Boston: (Tichnor and Company). , 1886), p. 271. ↵

- Robert C. Winthrop in an address to Harvard College Alumni as reprinted by John H. Komlos, op. cit. , p. 167. ↵

- "Újházi László," Szabadság, 21 December 1911, Part II, pp. 8-9. ↵

- Joseph Szeplaki, The Hungarians in America 1583-1974: A Chronology & Fact Book (Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: (Oceana Publications). , 1975), p. 13. ↵

- Edmund Vasváry, Lincoln's Hungarian Heroes (Washington, D.C.: (The Hungarian Reformed Federation of America). , 1939). ↵

- Ibid. , p. 86. ↵

- Ibid. , p. 59. ↵