Section III: The Hungarian Communities of Cleveland

The Formative Period (1880-1910)

A.KOSSUTH IN CLEVELAND

Following the defeat of Hungary’s War of Independence in 1848, Louis Kossuth, Governor of the short-lived Republic, fled into exile. The United States government, sympathizing with the cause of Hungary, invited Kossuth to visit the United States in 1851. During the nine-month tour, Cleveland was one of the many American cities Kossuth visited.

Two Hungarian organizations were established for the purpose of preparing the trip of Louis Kossuth to Cleveland, at a time when barely a handful of Hungarians had settled in the city. The first one, The Hungarian Society of Cleveland, was headed by I.C. Vaugham, editor of The True Democrat, a Cleveland daily. The other was the Ladies Hungarian Society of Cleveland, whose President was Moses C. Younglove. These organizations continued in support of the Hungarian cause for a number of years following Kossuth’s visit.

Moses C. Younglove describes the impact of Kossuth’s visit in his “Recollections”, dated May 29, 1891:

… This was at the time of his visit to Cleveland in the winter of 1852. I was one of a committee of citizens who went to Pittsburgh to invite and escort him to our city. While he was here, he called at my house and I still have the chair in which he sat. I was there living in a house where Plymouth Church now stands. In 1866—I saw him in Italy and he well remembered that call which he made at my house. He was the one who introduced the soft hat into our country and they soon became generally worn. His picture on the bill is a correct figure of the one he wore. (Courtesy of the Western Reserve Historical Society Library)

The train bringing Kossuth and his followers to Cleveland left Pittsburgh on January 31, 1852, and made a number of stops in the small Ohio towns of Palestine, Salem, Alliance, Ravena, Hudson, Bedford and Newburgh. Theresa Pulszky and her husband Francis accompanied Kossuth on his tour. This is how Mrs. Pulszky recounts the journey to Cleveland:

When we now reached the boundaries of the State of Ohio, we saw that this assertion was true. At every railway station we found thousands assembled, eager to see the apostle of liberty. Deputations were waiting with “material aid” for Hungary, and presented resolutions passed by Town Councils and popular meetings approving the principles he preached. In one place where we stopped for only a few minutes, people, in good earnest, requested Kossuth to climb up on the top of the railway cars, that they might see him better. At Alliance, several deputations were awaiting us.[1]

In Newburgh, Cleveland’s Committee welcomed Kossuth; it included: Mayor Case, General Wilson, Handy Parker, Charles Bradbur and M.C. Younglove. As Kossuth’s train pulled into the station at Cleveland, a detachment of the Cleveland and Ohio City Artillery fired a round of cannon, announcing the arrival of the anxiously awaited Governor of Hungary. Kossuth arrived around 11:00 p.m., but the crowds waiting on the streets to catch a glimpse of him did not disperse, despite the lateness of the hour. Cleveland’s German citizens welcomed him with a torchlight procession and music, they serenaded Kossuth from the streets outside of the hotel where he stayed, the American House.

On Sunday, February 1st, Kossuth rested. On February 2nd at 11:00 a.m., he spoke to a vast crowd gathered in front of the American House on Superior Avenue. The street was overflowing with people and all traffic was halted. The windows of the surrounding buildings were full of women waving kerchiefs in applause of Kossuth’s oration. In the afternoon, Kossuth spoke at the Cleveland “Melodeon”, where the Associations of the Friends of Hungary greeted him. The tickets, costing $3 for general admission and $4 for reserved seats were all sold in advance. (At this time, this was a sizable sum of money, considering that the average workman’s wages were approximately $1.50 a day.) The high price of admission was willingly paid by hundreds. Kossuth’s enthusiastic and fiery orations made many indifferent Americans into avid supporters of the cause of Hungary.

On February 3rd, private receptions were held in honor of Kossuth at Weddel House. On the following day, early in the morning, Kossuth departed for Columbus, accompanied by several state representatives and senators who had come to Cleveland to welcome Kossuth and to escort him to the State Capitol. Governor Woods headed the Welcoming Committee of Legislators.

In Columbus, the Senate of the State of Ohio passed the following resolution in support of the cause of Hungary by a vote of 16 to 8:

…That the Governor of Ohio be authorized, and is hereby instructed to deliver to Louis Kossuth, the Constitutional Governor of Hungary, on loan, all the public arms and ammunitions of war belonging to the State, which remain undistributed, to be returned in good order upon the achievement of Hungarian Liberty.[2]

Following the visit of Kossuth, a group of Hungarian Jewish families settled in Cleveland. The Black family, Deutsch brothers and Soma Schweiger became Cleveland’s first Hungarian businessmen. These families paved the way for the less advantaged Hungarian immigrants who were to follow.

Morris Black and his brother David went into the garment business and founded the Black Cloak Co. Morris Black had two sons, Joseph and Louis. In 1888, Joseph was appointed American consul to Hungary by President Grover Cleveland. Louis Black served in Company A of the 150th Ohio Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War. He was the first Hungarian elected to Cleveland’s City Council, serving from 1881-1883. Louis also became the city’s first Director of Fire during the administration of Mayor Rose. In 1881, Louis Black became President of the Bailey Company, a large department store located at Ontario and Prospect Avenue. He originated the idea of department store branches in the Cleveland area.

In 1863, Morris Black founded the Hungarian Aid Society. It was the first such organization founded for the purpose of providing sick benefits and aid for needy Hungarian immigrants. In 1881, it was reorganized as the Hungarian Benevolent and Social Union, which commemorated its 80th year in 1961.[3]

B. THE STREETS WERE NOT PAVED WITH GOLD

Around the turn-of-the-century, the flow of immigrants to the United States from Hungary increased at a phenomenal rate. According to census figures, between 1870 and 1920, approximately one million Hungarians immigrated to the United States. By 1900, the number of Hungarians in Cleveland had reached 9,558.[4]

There were several reasons for the mass emigration from Hungary: the population of central Europe had increased markedly while land ownership remained in the hands of a relatively small percentage of the population. Employment opportunities were limited, industry was not yet developed and the pay received by migrant farm workers and day laborers was meagre by any standard. Other significant factors encouraging immigration were: letters sent by fellow countrymen already in America relating the favorable working conditions and high pay, agents sent by American companies to recruit laborers, passage could be gained for as little as $25.

The majority of Hungarian immigrants who came at this time were agricultural workers. They came with the intention of staying only a few years to save enough money to return and purchase land in their homeland. More than half of those who arrived prior to 1914 managed to return. A large percentage of the Hungarians who came to Cleveland around the turn-of-the-century were from upper Hungary, namely from the Counties of Szepes, Sáros, Abaúj-Torna, Zemplén, Liptó, Árva, Trencsén, Ung and Bereg; from one district in particular, Bodrogköz, more than 7,000 Hungarians immigrated to the State of Ohio.[5] Letters providing testimonials, in addition to a strong desire to live near friends and neighbors in America caused this “group” migration.

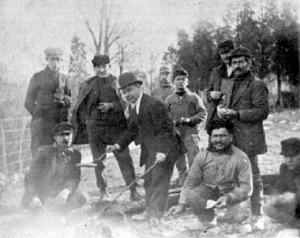

The first Hungarians of this mass immigration who came to Cleveland were from the County of Abaúj-Torna, village of Buzita.[6] The first arrivals came in 1879; they included: Miklós Veres, György Kupecz, András Vaskó and Mihály Timkó. They were followed the next year by István Veres and István Timkó. In 1880, from the same county, village of Csecs came József Schwab, János Kovács, György Sztrick, János Bencze, György Weizer, Pál Kiss, András Csepely, János Dobovitzky, János Weizer, András Bartkó and family, András Kertész and family, János Rick, János Makránszky and the Somossy family. From the village of Göncz came András Targiszer, the Molnár, Takács and Soltész family and from the County of Sopron came István Jessy, Josef Csizmadia and his brother, János.

The residents of Cleveland were not particularly anxious to receive the new group of Hungarian immigrants. These first Hungarian families settled around the southeast edge of the city, close to the factories where they worked. The streets where they lived were unpaved and dark. According to one source, they were afraid to speak in their native language. The more established immigrant groups, such as the Irish, resented their arrival and allegedly, threw stones at the Magyars if they spoke in any other language than English in the streets.

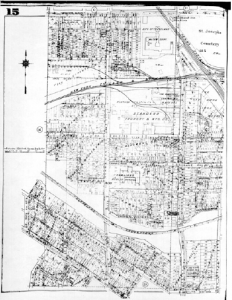

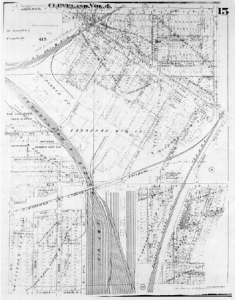

A distinct Hungarian neighborhood came into being during the mid-1880s. The Hungarians settled around Madison Street (now East 79th) and Woodland Avenue from East 65th Street onward.[7] Streets with particularly heavy concentrations of Hungarian residents included Bismarck, Rawlings and Holton. Two of the first Hungarians who settled in this area were János Makránsky and András Kuzma.

The neighborhood developed near several major factories on the southeast section of Cleveland. The Hungarians initially found work at the Eberhardt Manufacturing Company, Mechanical Rubber Works, National Malleable Steel Castings, Ohio Foundry, Standard Foundry, Van Dorn Iron Works, Old Glidden Varnish, Cleveland Bronze and Carlin Bronze.

These Hungarian immigrants were in Cleveland for the purpose of saving money and returning to their homeland. They viewed their stay as temporary and the way they lived reflected this. The majority were men who were single or had left their families behind. These men lived in boarding houses, run by the few women who had immigrated with their husbands.

A study of the Immigration Commission of Cleveland completed around 1914, revealed that Magyars had the highest proportion of families of any “race” whose wives add to their income by going out to work or keeping boarders: 71 percent of the wives of Magyar families reviewed earned wages or kept boarders.[8]

Before the outbreak of the First World War, managing a boarding house was the most effective way a woman could earn money. It was, however, the most grueling work imaginable. Usually, fifteen to twenty boarders shared a house. The men worked in shifts, which meant that the managing woman had to be “on call” at all hours of the day and night to serve the meals. In addition to the cooking, the woman prepared the lodgings, laundered and mended the soiled clothes and cleaned the house. For all this, each boarder paid $3 a month.

The incidents recounted by the Hungarian women who ran the boarding houses are interesting and informative accounts which play a crucial part in the reconstruction of immigrant history. Many of these interviews were conducted by Theodore Andrica, one-time writer for The Cleveland Press. One boarding house keeper never went to bed on Monday night. Monday was designated washday and in order to keep up with the rest of the weeks work, all the wash had to be completed by Tuesday morning. One example of many: Mrs. Mary Csupp raised six children singlehandedly by managing a boarding house; her husband died suddenly after working fourteen years in a steel mill, without so much as a week’s vacation.

The boarding house keepers witnessed the countless personal tragedies which befell the immigrants. One man was fatally burned in a steel mill accident only a month after his arrival in the United States. Friends collected money for his burial. His mother in Hungary lost her mind upon hearing of her son’s tragic death. Another, who had already saved enough to send for his wife and children, was killed while crossing the railroad tracks to go to work.

These women were the only source of female companionship for many of their boarders. They were subjected to daily struggles with these lonely and unhappy men. Often, they were even humiliated and taken advantage of.

The Hungarian immigrants quickly realized that dollars were not earned easily in America. Handicapped by language barriers, they were forced to take any available job. In Cleveland, they found jobs in the steel mills, iron works and foundries. The work was back-breaking and dangerous; industrial accidents and fatalities on the job were common-place occurrences.

Hungarians in Cleveland earned a reputation as hard working and tolerant and according to some sources, employers sought them out when hiring. Hungarian immigrants worked diligently because, for the most part, they had no other choice. It was not out of any great affinity for grueling factory work. They were determined to establish themselves financially in America in order to return to their homeland.

The immigrants suffered an incalculable amount of loneliness, frustration and alienation during their first few years in this country. The first Hungarian Roman Catholic priest in Cleveland, Reverend Charles Boehm, wrote about some of the “problems” within the community in the Hírnök, the parish bulletin of St. Elizabeth of Hungary Roman Catholic Church. Boehm was a dynamic strong willed individual who accomplished a great deal with what limited assistance his parishioners could provide. One charter member of the church recounted: “I remember well when Father Boehm waded in mud with his rubber boots on to visit every Hungarian home. Even better, I remember how he used to go to saloons and by sheer force of argument take the Hungarians out.”[9]

The Hírnök contains many writings of Boehm through which various impressions of the early Hungarian community were conveyed. In one passage, the immigrant priest wrote the following: “Why is it that for months in advance the Hungarian House dance hall is rented out on every payday? Even during Lent, the Hungarian neighborhood is abound with twenty-five cent admission fee events. Yet, during these same weeks, there is hardly an individual who donates a nickel to the church collection basket.”[10]

Boehm regularly expounded on the evils of drinking alcohol and once wrote the following:

As soon as one or two Hungarians move into a street, the English residents leave because of the way the newcomers behave, and who can blame them? Who could tolerate the yelling, screaming and gallivanting about which goes on into the small hours of the morning?[11]

Through the Hírnök, Reverend Boehm provided his parishioners with moral and religious guidance, as well as assistance in adjusting to life in America. He often wrote about the many sufferings endured by the Hungarian immigrants and referred to America as “the land which not only gives bread, but gravestones as well.”

The original Hungarian neighborhood around Bismarck and Rawlings Streets in the southeast section of Cleveland was not the only area which attracted the immigrants. Several hundred immigrants from the village of Metzenzefen settled on the west side of the city around the marketplace- between Lorain Avenue and Abbey Avenue. A fellow villager, Theodore Kundtz, founded the Kundtz Manufacturing Company some years earlier and employed many cabinetmakers from that district in Hungary. The west side Hungarians were mainly from upper Hungary, in particular, from the counties of Szepes and Abaúj.

Hungarians living on the west side did not experience the initial animosity of more established ethnic groups because the majority spoke at least one other language (usually German) in addition to Hungarian. Moreover, they did not settle in separate streets or districts, but scattered throughout the near west side. The west side Hungarians considered themselves superior to the Hungarians living on the east side. This was because the majority of the west siders were skilled cabinet-makers, whereas the east siders were generally unskilled laborers working in heavy industry.

The initial hardships were gradually overcome. Many Hungarians saved up enough capital, left the factories and started their own businesses. The economic status of the community improved considerably with each generation. The first saloon owner was Imre Schwab who opened a tavern around the area of Bismarck Street in 1888. Joseph L. Szepessy opened the first foreign exchange and real estate office on Buckeye Road in 1890. In 1901, he was named the first Hungarian member to the Board of Directors of the Woodland Avenue Savings and Trust Company. Szepessy wrote of this appointment: “despite twelve ‘Americans’ all vying for the post, they still chose me.”[12] The first clothing store on Buckeye Road was owned by John Weizer in 1895. Weizer later opened a foreign exchange and steamship ticket office at the same site.

The wealthiest Hungarian families on Buckeye Road: the Weizer, Szepessy, Gedeon and Apáthy families started by opening steamship ticket and currency exchange offices. This business was made lucrative by the hundreds of thousands of immigrants going back and forth between the homeland and America. “Migrating birds” they were called; they went home to Hungary for harvest time and returned during the winter months to work in a factory or steel mill. After 1924, when immigration laws were stiffened, these “first” families expanded their businesses into real estate.

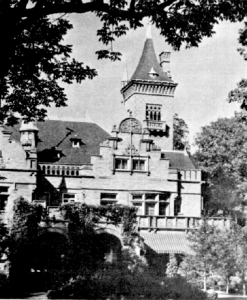

One of the most successful industrialists in Cleveland’s history was Theodore Kundtz, who arrived in 1873 at the age of 21 with a total capital of $10. Kundtz was from the village of Metzenzefen, County of Abauj. As a skilled cabinetmaker, he was hired by the Whitworth Company to make sewing machine cabinets. In 1876, Kundtz bought out the shop and through much hard work and good business sense, built the Kundtz Manufacturing Company, which supplied the wooden cabinet parts for the White Sewing Machine Company. By 1900, Kundtz Manufacturing employed some 2,500 skilled workers, most of whom were Hungarian immigrants. Theodore Kundtz was often quoted as saying: “You’re crazy to work for me. Work for yourselves, start your own businesses, that’s the only real way to make money.” The company expanded into manufacturing church and school supplies and made truck bodies for the Allies during the War. Later, the Kundtz Manufacturing Company merged with White Sewing Machine, becoming the White Consolidated Company, today a billion dollar conglomerate corporation.

There were other success stories as well. By 1905, the flow of skilled tradesmen from Hungary increased: butchers, shoemakers, tailors, carpenters, machinists, mechanics, etc. The advertisements found in the 20th Anniversary issue of Szabadság are indicative of the multitude of Hungarians in these trades. The issue contains over ten Hungarian-owned grocery and butcher shops, six clothing outlets, six real estate agents and numerous hardware stores, bakeries, pharmacies, taverns and barber shops. The biographical sketches of the owners contain valuable insight into the lives of these first Hungarian businessmen in Cleveland. Many prided themselves on admitting that when they first came to America, they worked in factories. The White Cross Pharmacy at West 25th Street and Lorain Avenue, “served its customers only in Hungarian.” The Szabo brothers, owners of a meat processing plant, were known as the “Kolbasz Kings”. Greszingh Louis, a Hungarian photographer on West 25th Street, boasted of having the “largest store in Cleveland.” Steven Jakab was initially a tavern owner; after saving enough capital, he opened Cleveland’s first Hungarian-owned funeral parlor on Buckeye Road. The slogan of the Red Cross Pharmacy at Buckeye and East 89th Street read: “100,000 Hungarians regained their health by coming to our pharmacy.”

That was in 1911. It is interesting to note the advances made by the business and professional community by 1940 when examining the 50th Anniversary yearbook of the same newspaper. Biographical sketches are given of some twenty grocers and twenty-five restaurateurs. Significant, however, were the increased number of Hungarian professionals: lawyers, doctors and dentists. The number of machine shops owned by Hungarians were also substantial. Hungarian contributions to the machine manufacturing industry are frequently hidden by the anonymity of the company names, such as: Western Aluminum Match Plate Company, Clybourne Pattern Works, Proof Machine & Brass Foundry Company, Palfy-Bock Die & Mold, etc.

C. A COMMUNITY COMES INTO BEING

The development of the Buckeye Road Hungarian community on the east side was largely responsible for the influx of Hungarians to the City of Cleveland in the early 1900s. Generally, Hungarians were more than willing to immigrate to a city or town where their fellow countrymen had already settled. The ethnic enclave eased the initial shock of immigration by providing assistance in finding employment and companionship with others of the same background. This effect compounded itself-the more the neighborhood grew, the more immigrants came and vice-versa. Cleveland’s Hungarian immigrant population rose sharply from 9,558 in 1900 to 43,134 by 1920. Hungarians constituted 8 percent of the city’s foreign-born population in 1900, which increased to 18 percent by 1920.[13]

Effective organizations and institutions were made possible by the concentration of Hungarians in one neighborhood. In 1911, one newspaper describes the Buckeye Road community as a large Hungarian city, with many thousands of inhabitants, several churches, schools, six newspapers, and even the business district’s official language being Hungarian. According to one author’s estimate, 81 Hungarian organizations were active in Cleveland by 1911.[14]

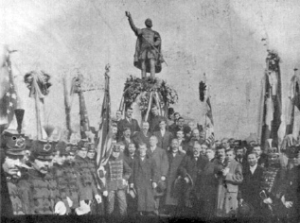

Large-scale projects, involving the support of all Hungarians living in Cleveland, stimulated a sense of community awareness and pride. The statue of Louis Kossuth was erected in 1902 when 10,000 Hungarians lived in Cleveland. The project received much applause and praise from local dignitaries and the general public, which further heightened the community’s sense of accomplishment. Another project, the founding of the United Hungarian Societies, also promoted unity and a sense of common purpose. The Societies was founded when only 12 organizations existed in the Hungarian community. It is today as it was at its founding, unique among all Hungarian-American organizations in the United States.

This sense of community awareness and unity was further enhanced as Cleveland became the leader and pace-setter for all Hungarian communities throughout the United States. Major movements of general interest to all Hungarian-Americans originated in Cleveland. The American Hungarian Federation was founded in Cleveland in 1906 to represent Hungarians living in the United States and to safeguard their rights as American citizens. The movement to erect the statue of George Washington in Budapest was initiated and carried to fruition by Tihamér Kohányi, editor of the Szabadság, a Cleveland-based newspaper. These are but two of several examples.

The order in which the community organizations were established is noteworthy. First of all, the self-help/sick benefit societies were organized. These societies were formed in response to a need for security at a time when social security, unemployment compensation and disability were unheard of in the United States. In a country which was foreign and many times hostile to these immigrants, they formed their own sick benefit and insurance organizations to provide this desperately needed security.

Interestingly, soon after these initial needs were met, numerous cultural, civic and community service organizations were initiated. The cultural foundations were laid nearly simultaneously with the establishment of the Hungarian community.

In 1886, the first Hungarian organization in Cleveland was formed as the result of a frightening incident in the neighborhood. An immigrant man died without friends or relatives and during the night he was carted away to an unknown destination. No one knew whether he had been properly buried. This disturbed the Hungarian community to such extent that soon an organization was formed-the Gróf Batthány Lajos Society, for the purpose of providing sick benefits and funeral expenses. It was named after Count Louis Batthány, Prime Minister of Hungary in 1848. The Society’s secondary aims included protecting the rights of Hungarian immigrants and informing Clevelanders about the Hungarian people, their customs and traditions.

The first Hungarian sick benefit societies in Cleveland were founded as independent organizations. The establishment of the Grof Batthány Lajos Society was followed by the Nicholas Zrinyi Sick Benefit Society and the Kossuth Society. Countless other mutual benefit societies, representing a vast variety of occupational, denominational, political and social circles, came into existence. One example of many, the Cleveland Hungarian Young Men’s and Ladies’ Society (1891), had assets exceeding $54,000, and membership reportedly at 1,020 in 1935.[15] The Society’s clubhouse at 8637 Buckeye Road was one of the social and civic centres of the Hungarian neighbourhood.

Other sick benefit and insurance organizations were founded for a dual purpose: to provide insurance and to bring together Hungarians of one denomination for the purpose of establishing a church.

Through the efforts of the King Saint Ladislaus Roman Catholic Men’s and Women’s Sick Benefit Society (1888), the first Hungarian Roman Catholic priest came to the United States and the first Hungarian-American church of the Roman Catholic faith (St. Elizabeth of Hungary) was established. St. Michael’s Sick Benefit Society, founded by eighteen Greek Catholic families in 1891, requested a Greek Catholic priest from Hungary and established St. John’s Greek Catholic church in 1894.

Soon after the churches were established, sick benefit and insurance organizations sprang up under the auspices of the churches. By 1919, there were nine sick benefit societies active at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Roman Catholic Church, four at St. John’s Greek Catholic Church and four at the First Hungarian Reformed Church in Cleveland. One of these organizations, the King St. Stephen Catholic Hungarian Insurance Society organized twenty-five chapters throughout Ohio and neighboring states with assets exceeding $300,000 by 1941.[16] Later, many of the local Catholic sick benefit societies became chapters of the American Hungarian Catholic Federation.

In addition to the numerous local societies, national Hungarian insurance organizations established various chapters in Cleveland. The oldest and largest of these organizations was the Verhovay Insurance Association, founded in 1886. The Verhovay operated forty-two branches in the State of Ohio and seven in the City of Cleveland.[17] Cleveland membership exceeded 2,500 by 1919. The American Hungarian Reformed Federation, founded in Cleveland in 1896, maintained 140 branches throughout the United States by 1919. The establishment of the first national Hungarian Catholic insurance organization, Virgin Mary Hungarian Patron Roman and Greek Catholic Association, took place in Cleveland.

Mutual benefit societies constituted a major segment of the organizational structure of the community. In the 35th Anniversary Booklet of the United Hungarian Societies, printed in 1935, twenty-eight of the sixty-one member organizations were listed as sick benefit insurance associations.

Tihamér Kohányi was an outstanding figure in the establishment of several major Hungarian-American institutions, among them the Szabadság, which became the largest Hungarian daily in the United States and the American Hungarian Federation, an umbrella organization representing Hungarian-Americans. As an unsuccessful candidate for the legal profession, Kohányi departed for the United States at the age of twenty-seven. At the time of his departure, he wrote:

I left [for America with light heart and baggage, with the strong conviction–on the basis of what I had heard from many-that no one has ever died of hunger in America.[18]

Kohányi’s first job was shoveling coal in the mining town of Eckley, Pennsylvania, earning 81 cents a day. After the first day on the job, the woman who managed the boarding house where he lived had to “squeeze the cramps out of his fingers.” Later, he worked at various odd jobs, as a travelling book salesman, a store clerk and a janitor.

During his travels, Kohányi made stop-overs in Cleveland and befriended the local Hungarian community. The only organization which was established at the time was the Gróf Batthány Lajos Society. He soon helped organize the Cleveland Hungarian Young Men’s and Ladies’ Society (1891) and wrote the first play presented by the group. The play was entitled “Greenhorns” and the presentation took place at Cincinnati Hall on Holton Avenue. According to Kohányi, this was the first Hungarian dramatic presentation in Cleveland.

Although the Hungarians in Cleveland had barely started building their community churches, organizations and businesses, already a strong need was felt for a Hungarian-language newspaper. Tihamer Kohányi met that challenge and founded the Szabadság (Liberty), which was first printed on November 12, 1891. This date marks the establishment of the oldest Hungarian-language newspaper in the United States which is still published today.

The task of establishing the Szabadság was formidable. A corporation was set up with two Hungarian industrialists, Joseph Black and Theodore Kundtz, each contributing $600. Pledges of $15 were made by 117 Hungarians, but barely 50 were paid.[19] These Hungarians doubted the project would materialize and were afraid of losing their money. They wanted some reassurance that the newspaper wouldn’t cease after a few editions.

It was the perseverance and enthusiasm of Kohanyi which finally made the Szabadság a success. In the first years, he did everything, from writing articles, typesetting, correcting and proofreading to selling advertisements. He acted as editor, manager, editorial staff and business manager; many times without knowing where his next meal was coming from. But Kohányi’s painstaking efforts finally paid off, the paper gradually increased in power and prestige.

In 1909, it became the largest and most powerful Hungarian daily in the United States. Szabadság celebrated the 20th year of its founding in 1911; President Howard Taft was present at the anniversary banquet honoring Tihamér Kohányi.

Through the Szabadság, Tihamér Kohányi exerted considerable influence upon the opinions and lives of Hungarian immigrants in the United States. For most, this Hungarian-language daily represented their only contact with news from the outside world and in particular, news from the homeland. Kohányi rallied Hungarian-Americans through his enthusiastic writings. Several historically significant projects were carried to fruition largely through his support: such as the Kossuth statue in Cleveland (erected in 1902) and the Washington Monument erected by Hungarian-Americans in Budapest in 1906. Kohányi served as President of the Budapest Washington Monument Association. Kohányi was also instrumental in founding the first Catholic Hungarian Insurance Association in 1897, and the American Hungarian Federation in 1906. In addition to all of these projects, during the first twenty years of its’ existence, the Szabadság collected more than $50,000 for Hungarian immigrants in distress: widows, orphans, striking workers and those made homeless by disaster in all parts of the United States.

Tihamér Kohányi died in 1913 and Hungarians all over the United States mourned their loss. His work and influence was far-reaching. His beliefs were best demonstrated by the platform of the Szabadság, which was printed on the front page of the 20th Anniversary Issue:

The Szabadság during all its years of existence was not merely a business concern, that attended only to the supplying of reading matter for its readers. It was a leader of all movements among Hungarians towards betterment and development; it has always strived for higher ideals; it has always taught the Hungarians to be good, law-abiding citizens of this country; it has always strived to protect the Hungarians from the dangers that menace the immigrants amongst their new surroundings and has performed many other services to this country and its countrymen.

The Honvéd Veteran Club, whose members included veterans of the 1848 Hungarian War of Independence, held a meeting in July 1901 to determine how the Cleveland community was going to commemorate the combined events of the 50th Anniversary of Kossuth’s visit to the United States and the 100th Anniversary of the birth of Louis Kossuth. Hungarian immigrants in Cleveland had vivid recollections of Kossuth and the War of Independence. Many of the immigrants’ fathers or grandfathers fought in the war and countless died. In their opinion, Louis Kossuth was the greatest hero of Hungarian history. In order that the commemoration be made in a manner befitting the occasion, it was decided to erect a statue of Kossuth in Cleveland.

The Kossuth Statue Committee was formed and considering the small size of the community, the project was brought to successful completion in a relatively short amount of time–one year. András Tóth was commissioned to sculpt an exact replica of the Kossuth statue he designed at Nagyszalonta, Hungary. Tóth donated his services to the Cleveland Committee and the Holland-American Steamship Line transported the statue across the ocean free of charge. Mayor Tom L. Johnson pledged his wholehearted support in finding a suitable location for the statue. Some Slavic groups, however, attempted to block the project completely and succeeded in preventing the statue from being erected on public square in the centre of the city. University Circle was finally chosen as the site of the statue, an area which in 1902 was considered to be an outskirt of Cleveland.

Letters were sent to the Commissioner of each county in Hungary requesting that earth from famous landmarks be sent to Cleveland for the base of the statue.[20] All the counties responded, with the exception of two. The statue of Kossuth in Cleveland was erected on soil from such historic places as: Arad (where thirteen Hungarian Generals were executed in 1849), the pass at Verecke, and the plain of Majthényi. Soil from the famous battlefields of Mohács, Nagy Salló, Debrecen, Kápolna, Szolnok, Fehéregyház and Kaponya were sent; in addition, from the fortresses of Gyulavár, Fogaras, Drégely, Komárom, Dévény, Szigetvár, Trencsén, Eger, Abaujvár and Alsóújvár. Earth collected from the graves of Lajos Kossuth and Áron Gábor was sent as well as from the castle of King Béla (Esztergom), the Hunyadi castle (Transylvania) and from the fortresses of King Matthias. Soil from the most famous landmarks in Hungary laid the foundation for the statue of Kossuth in Cleveland.

The unveiling ceremony was set for September 28, 1902. Hungarians from all parts of the United States journeyed to Cleveland to be part of the historical event. Thousands of people participated in the parade preceding the ceremonies which led from Public Square to University Circle. According to one source, the first groups were just arriving at the site of the statue when the last marchers were leaving public square, the distance between the two points being nearly eight miles. From the Italian community alone, 600 marchers paraded, all reportedly decked in Kossuth hats.

Dignitaries attending were: Mayor Tom L. Johnson, Honourable George Nash, Governor of Ohio, Senator M.A. Hanna, and Congressman T. Burton. Lajos Perczel presented the statue to the City of Cleveland in the name of all Hungarian residents. Mayor Tom Johnson accepted the generous gift and promised in his name as well as in those of his successors to act as faithful guardian of the statue.

The Kossuth Statue Committee was the forerunner of the United Hungarian Societies, founded in 1902 with twelve organizations. Its purpose was to “coordinate the cultural, charitable and welfare activities of the member societies, to represent the Hungarian Americans of Cleveland and to serve both the Hungarians and the City of Cleveland to the best of the ability of the organization.” The organization was unique at its founding, and it remains unique to this day.

The United Hungarian Societies organized and coordinated major projects which would have been impossible to achieve through individual organizations. The Kossuth statue in Cleveland was the first such accomplishment. Since the erection of the statue, the organization has sponsored the annual commemoration of the 1848 War of Independence, held on March 15, in addition to the “Magyar Day” Festival, sponsored each summer in July.

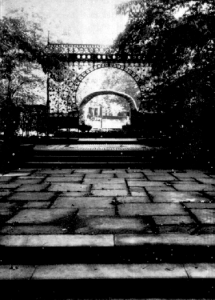

The United Hungarian Societies has been instrumental in promoting Hungarian culture in Cleveland. In 1924, the organization established the Baracs Library in the Cleveland Museum of Art as a tribute to the many contributions of the late Dr. Henrik Baracs. In 1930, a bust of Alexander Petofi, world-renowned Hungarian poet, was presented to the Cleveland Public Library. In 1933, the Societies took charge of the Hungarian Cultural Gardens in Rockefeller Park. Through the years, the busts of Ferenc Liszt, Endre Ady, and Imre Madách have been placed in the garden, as well as a magnificant wrought iron gate or “Székely Kapu”.

The records of the United Hungarian Societies demonstrate that in unity there is strength; the financial assistance provided by the organization through the years aided many in the United States as well as in Hungary. Some of the projects supported in Hungary were: the famine victims of 1923, aid for Hungarians expelled from their homes in Yugoslavia (1935), flood relief (1936), in addition to providing assistance to some seventeen hospitals, twenty-three veteran homes and seven war orphanages. In 1920, more than $18,000 was sent to Russia to free Hungarian prisoners of the First World War.[21]

The welfare of Hungarians living in the United States has always been a prime concern of the United Hungarian Societies. In 1928, food and clothing was sent to striking miners in Pennsylvania. During the depression, the Societies set up a job placement centre in Cleveland. In 1936, donations were made to the American Red Cross for disaster work. Following the Revolution of 1956 in Hungary, the U.H.S. coordinated the relief efforts and resettlement programs for the influx of refugees. The United Hungarian Societies celebrated its 75th year in 1977 with over 50 member organizations.

D. RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS

Cleveland was the first location of numerous Hungarian church denominations in North America, namely: the first Hungarian Roman Catholic Church (1892), the first Hungarian Reformed Church (1891), and the first Hungarian Greek Catholic Church (1892). In the 1890s, churches of these three denominations were founded and built by the Cleveland Hungarian community on lower Buckeye Road. Mass Hungarian immigration to Cleveland around the turn-of-the-century signalled the development of additional congregations. In the early 1900s, eight Hungarian churches of six denominations were established on the east side and the west side, in addition to three Hungarian Jewish temples.

Cleveland was the first and often times the only location in the United States of unique Hungarian religious institutions. The first Hungarian Baptist Seminary was founded on Holton Avenue in the early 1900s to prepare young men for the Baptist ministry. The first Hungarian Lutheran Orphanage was built on Rawlings Avenue in 1913. The first Hungarian Greek Catholic elementary school was constructed in 1954 under the auspices of St. John’s Greek Catholic Church.

At present, all the Hungarian churches established around the turn-of-the-century are maintained by Hungarian congregations. Regionally, there are seven on the east side and four on the west side. Distribution according to denomination is as follows: three Roman Catholic, two Reformed, two Greek Catholic, two Lutheran, one Presbyterian and one Baptist. The three Hungarian Jewish orthodox churches are the only ones which have ceased altogether, due to in large part, the attraction of younger members to temples with reformed practices.

The Roman Catholic Churches

The King St. Ladislaus Hungarian Roman Catholic Men’s and Women’s Sick Benefit Society, founded in 1888, was the first organization uniting Hungarian Roman Catholics in Cleveland. According to the organization’s 50th Anniversary Booklet, it was founded before any Hungarian Roman Catholic church or priest existed in the United States. Founded by laymen who were led by János Weizer, the Society’s ultimate purpose was to establish a church where Hungarians of the Roman Catholic faith could worship.

Initially, they joined with the Slovaks and built St. Ladislaus Roman Catholic Church, at East 92nd and Holton Avenue. Difficulties arose, however, and the Hungarian congregation, steadily increasing in numbers, felt it was necessary to make the break and establish their own church. The King St. Ladislaus Society requested a Roman Catholic priest from Hungary through Bishop Horstmann of Cleveland and the papal prelate in Washington. It was through the efforts of this organization that the first Hungarian priest, Reverend Charles Boehm was sent to the United States, arriving in Cleveland on 1 December 1892.

From the day he arrived in 1892 until his retirement in 1927, Reverend Boehm worked tirelessly in the service of Hungarians in Cleveland as well as in the United States. He established St. Elizabeth of Hungary Roman Catholic Church in Cleveland and is credited with the founding of more than twelve Hungarian Roman Catholic churches in the northeast United States. At his funeral in 1931, he was eulogized as “the best loved and best known priest” of his nationality in America.[22]

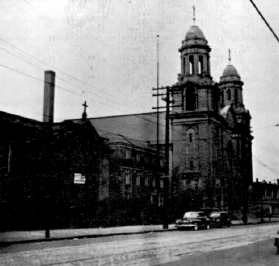

Following his arrival, Reverend Boehm set to work registering parishioners. In that year, he registered 220 families, 340 single adults and 507 children, or a total of 1,287 souls.[23] The first mass celebrated by Reverend Boehm was held in the Chapel of St. Joseph’s Orphanage (Woodland Avenue) on December 11, 1892. This date marks the establishment of St. Elizabeth of Hungary Roman Catholic Church, the first Hungarian Roman Catholic church in North America.

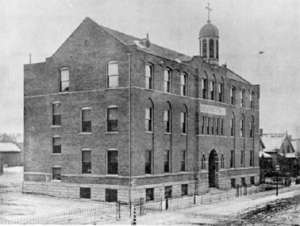

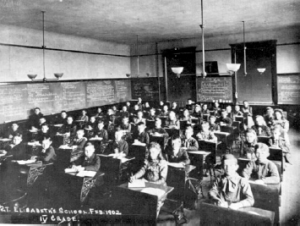

With an initial capital of $134.82, Reverend Boehm organized the building of a brick church at Buckeye Road and East 90th Street, which was completed eight months after his arrival. Soon afterwards, a wooden frame schoolhouse was built. In 1900, an even larger three-storey structure school building was completed to house the ever increasing number of children. By 1919, the enrollment of St. Elizabeth Elementary School had reached 1,114.

In 1894, Reverend Boehm founded the Magyarországi Szent Erzsébet Amerikai Hírnöke (St. Elizabeth of Hungary’s Herald in America), which served not only as a parish bulletin but also as a valuable religious newspaper and guide for immigrants whose only source of religious instruction was the local parish itself. In its second year, the number of subscribers had already reached 320 in Cleveland, 700 in the entire U.S. and 11 in Hungary.[24] Reverend Boehm donated all income from the newspaper to the building fund of the parish; he served as editor until 1907. In 1901, the newspaper was renamed Katolikus Magyarok Vasárnapja (Hungarian Catholics’ Sunday), a weekly newspaper which is still in existence today.

Reverend Boehm initiated the campaign to build the great stone church which is the present structure located at Buckeye Road and East 90th Street, the building of which was completed by Rev. Julius Szepessy in 1922. Reverend Szepessy became pastor in 1907, when Reverend Boehm gave up his pastoral duties in order to do missionary work among Hungarians in the United States. During this time, St. Elizabeth’s Hall was also completed, which became the social and religious meeting centre of “Little Hungary” on Buckeye Road. In 1923, Reverend Boehm was called back to St. Elizabeth’s due to the death of Reverend Szepessy. He served again as pastor until his retirement in 1927.

Since then, three other pastors have served the parish: Right Reverend Monsignor Emory Tanos, who served for more than forty years, Reverend Julius Záhorszky and Reverend John Nyeste (present pastor).

St. Elizabeth of Hungary has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places by the United States Department of the Interior and has been designated as a historic landmark by the State of Ohio and the City of Cleveland. The parish celebrated its 85th year in 1977.

Hungarians on the west side grew weary of travelling nearly 1 ½ hours to St. Elizabeth Church on Buckeye Road and decided that the time had come to build a Roman Catholic Church on the west side of Cleveland. With the support of Monsignor Boehm, St. Emeric Parish was established and placed under the guidance of Reverend Joseph Hirling in 1904.

Reverend Stephen Soltész, who became pastor in 1905, gathered and registered the widely scattered parishioners on the near west side. On January 22nd of that year, a wood frame church, located at Bridge Avenue and West 24th Street was dedicated. Reverend Soltész directed the purchase of the property surrounding the church, including homes, and renovated them to serve as a school. The Ursuline Sisters taught in the school where more than 150 children attended. Reverend Soltész conducted classes in Hungarian language instruction, history and geography. In 1909, he founded a Catholic Hungarian newspaper, Haladás (Progress). In 1911, Reverend Soltész was appointed to a church in Lorain, and was replaced by Reverend József Szabó. Two other pastors, Reverend József Péter and Reverend John M. Rácz, served the parish until 1920.

Fire destroyed the wooden church in 1915. A few years later fire again ravaged Annunciation Church a few blocks away where the congregation had relocated. In 1924, St. Emeric Church was purchased by the Union Terminal Company, which was completing the construction of the Terminal Tower in downtown Cleveland. The Company required the land for railway tracks which led to the Tower’s train depot.

In 1925, the present church and school building were built under the direction of Reverend Joseph Hartel. The Daughters of the Divine Redeemer Sisters taught in the new school. Reverend Hartel was succeeded by Reverend John B. Mundweil, who served as pastor of St. Emeric Church for over thirty years. Reverend Mundweil became a pioneer among the priests of the diocese in caring for and educating the mentally retarded and handicapped.

Since 1965, Reverend Francis Kárpi has served as pastor of the parish. Father Richard Orley, a third generation Hungarian-American assists at both St. Emeric and St. Elizabeth Roman Catholic Churches. Reverend Orley learned the native tongue of his grandparents to be able to work more effectively within his ethnic community.

By the 1920s, the increasing number of Hungarian Roman Catholics on upper Buckeye Road necessitated the construction of another Roman Catholic church, St. Margaret of Hungary at East 116th Street. At a time when walking was the primary means of transportation, St. Elizabeth of Hungary (East 90th) was at a considerable distance for the parishioners living around upper Buckeye Road.

In 1918, Father Richard Roth was named administrator to the newly-formed parish. Two years later Father Ernest Rickert, who received his education in Hungary, was appointed first pastor of St. Margaret of Hungary Church. Under his direction, a wooden church and a small recreation center were constructed in 1922. In 1927, Father Andrew Köller became pastor of the church, serving in this capacity for more than thirty years. Parishioners remember him as the “Miracle Man” of the parish.

The leadership and faith demonstrated by Reverend Köller inspired all around him. In 1928, plans were initiated for a new church and school building; a loan of $200,000 was applied for and granted. The new church was constructed and the dedication took place in October 1930 by Bishop Joseph Schrembs of Cleveland. Through the painstaking efforts of Reverend Köller and the parishioners, the church survived the Great Depression, despite the enormous amount of annual interest due on the loans received. The mortgage was amortized in 1946.

In 1925, Hungarian Greek Catholics living on the west side separated from the east side congregation and established St. Michael’s Greek Catholic Church at 4505 Bridge Avenue. The first pastor of the parish was Reverend Father Basil Béres.

Under the direction of Reverend Stephen Poratunszky, a church hall, also utilised as a school building, was built in 1935. For many years, the Hungarian boy scouts used these facilities for meetings and special events. Other pastors serving the congregation included: Reverend Father Theodore Fedás and Reverend John Kovács.

The Greek Catholic congregation on the west side has always been relatively small, with membership averaging 100 families.

The Reformed Church

The history of the Hungarian Reformed Church in Cleveland began on the west side in 1890. In that year, Reverend Gusztáv Jurányi, the first Hungarian Reformed minister in Cleveland preached the first sermon to a Hungarian congregation in a church on West 32nd Street near Lorain Road. Initially, the east and west side congregations worshipped together. The east side congregation was first to construct a church in 1894, thereby moving the Hungarian Reformed congregation to the east side. This Cleveland congregation was the first Hungarian Reformed congregation to be organized in the United States, closely followed by one in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Construction of the church was initiated by Reverend Jurányi but completed by his successor, Reverend Sándor Harsányi in 1894. The site of the church was at East 79th and Rawlings Avenue. In 1898, Reverend Elek Csutoros was elected pastor of the congregation. Reverend Csutoros served for thirteen years, after which time he was succeeded by Reverend Alexander Tóth. The increasing congregation soon necessitated expanding the original church structure. The church was rebuilt and expanded twice, in 1904 and again in 1929.

By 1919, membership reached 650 individuals or 350 families. Saturday school Hungarian language and religious instruction classes were held as well as every day summer school classes. On the average, 600 children attended these sessions.

In 1925, under the leadership of Dr. József Herczeg, the congregation purchased land at the corner of Buckeye Road and East Boulevard to build Bethlen Hall. This massive structure soon became one of the cultural and civic centers of the Cleveland Hungarian community. Dr. Stephen Szabó, who became pastor in 1947 and has led the congregation ever since, directed the construction of a new cathedral next to Bethlen Hall. The new cathedral, built in Romanesque style, was paid off in record time-the shortest in the history of the congregation.

In 1967, membership reached 1,200 families, representing the “largest Hungarian-American congregation.”[25] Today that number has declined somewhat; however, the church is still strongly supported by a large number of second and third generation Hungarian-Americans and their families.

In 1906, under the direction of Dr. Elek Csutoros, the west side congregation separated and formed the West Side Hungarian Reformed Church. The following year, Reverend Károly Erdei became first pastor of the congregation and two buildings were purchased on Monroe and West 25th Street to facilitate a church and a school. In 1913, Reverend Erdei was succeeded by Dr. Elek Csutoros, who served as pastor until 1926. In 1923, the church which was used previously by the congregation at West 32nd Street and Carroll Avenue was purchased from the German Reformed congregation. The church hall, Calvin Hall, became a cultural and social centre for the west side Hungarian community. Reverend Csutoros organized the church Sunday School as well as summer Hungarian language instruction for the children.

In 1926, Reverend Edmund Vasváry was elected pastor of the church. Reverend Vasváry later became a prominent researcher of Hungarians in America, with special reference to Hungarians who fought in the Civil War. In 1936, Reverend Vasváry was replaced by Reverend Matthias Daróczy, who served as pastor for nearly thirty years. During the pastorate of Reverend Daróczy, the congregation increased in membership and became a viable force in the Hungarian community of Cleveland. The church was instrumental in aiding hundreds of “D.P.s” who came after the Second World War as well as many homeless refugees who fled after the Hungarian Revolution in 1956.

The present pastor is Reverend Aaron Elek, who has served in this capacity since 1963. In response to the needs of the congregation, a new church was recently purchased at West 150th Street and Puritas Road. The congregation relocated in 1976 and simultaneously, construction of a new church hall was initiated.

The new hall, costing $450,000 was completed in September 1978. This modern facility serves as the new center for Hungarian community activities in Cleveland. Of the Hungarian churches, the congregation of the West Side Hungarian Reformed Church presently represents one of the largest and most active.

The Lutheran Church

Some twenty Hungarian Lutherans held their first meeting in 1905 and shortly afterwards, on April 23, 1906, they were granted a charter to establish an independent congregation. The first minister, Reverend Stephen Ruzsa arrived from Hungary in 1907 and within a few months the congregation purchased a church and schoolhouse on Rawlings Avenue. By 1911, summer school classes were organized with over seventy children attending Hungarian language instruction. In 1913, the Hungarian Lutheran Church founded and financed the first Hungarian Lutheran Orphanage in the United States. The orphanage operated successfully with more than forty children until its closing in 1920.

Reverend Stephen Ruzsa was succeeded by his brother, Reverend László Ruzsa, in 1923. Reverend Andor Leffler became pastor in 1934. Under his leadership a new church was constructed to accommodate the ever increasing number of parishioners. The new church, located at Buckeye Road and East Boulevard, was dedicated on May 4, 1941. In 1943, the mortgage for the newly constructed church was amortized and in 1954, the construction of a new educational center was completed. Membership reached 1,000 families in 1950. Reverend Gábor Brachna has served the parish since 1955.

The West Side Hungarian Lutheran congregation was organized in February 1938 with eleven members. Reverend Gábor Brachna, first minister of the newly formed congregation took charge in March of the same year. Soon afterwards, the congregation purchased a student dormitory on West 28th Street, which was then converted into a church. The new facility was dedicated in October 1938. By 1940, membership reached 125 families.

In 1950, the need for a new church became evident due to the increasing numbers of parishioners. Furthermore, by this time the church was located at a considerable distance for most members, who had relocated further west in the suburbs of Cleveland. A new church was constructed at West 98th Street and Denison Avenue, its dedication took place on March 19, 1950.

Reverend Brachna was succeeded in 1955 by Reverend Aladár Egyed, who served as minister for a few months. Reverend Imre Juhász became pastor in 1956 and has served the congregation since. One hundred and eight freedom fighters were welcomed and given temporary homes by the church after the Hungarian Revolution in 1956. At present, 230 parishioners regularly attend services.

The Presbyterian Church

The Magyar Presbyterian congregation was organized on May 24, 1914 by a handful of people under the leadership of Reverend Julius Kish. At first, the congregation initiated a number of community service projects, such as English language instruction classes for adults as well as a kindergarten for pre-schoolers.

The congregation’s first church was constructed in 1915 at the corner of Buckeye Road and East 103rd Street. However, this location proved to be at a considerable distance for most parishioners and a few years later, a new church was built on upper Buckeye Road at East 126th Street. This new church, which is the present location of the congregation was dedicated on January 12, 1919.

Reverend Kish retired in 1926. Reverend Béla Bashó served the congregation until 1929, when he was succeeded by Reverend Stephen Csutoros, who was pastor of the church for forty years. Reverend Csutoros guided the congregation through many difficult years, including the Great Depression and the Second World War.

He maintained an effective radio ministry, reaching thousands through the “Hungarian Radio Church” from 1940 through 1959. In 1956, Reverend Csutoros travelled to Austria to be of personal assistance to the homeless refugees who fled after the Hungarian Revolution. In 1969, Reverend Csutoros retired. The present pastor is Reverend Ferenc Erdei.

The Baptist Church

Hungarian Baptists were already organized in Cleveland in 1903. At first they met in two different buildings on East 79th and on Holton Avenue. Within a few months they purchased the First German Christian Alliance Church, which served as their first permanent location. Using the church as a meeting place, the congregation organized a band and a choir in order to preach gospel in the streets.

In June 1908, Reverend Stephen Orosz became the first minister of the small but determined group of forty-two members. In 1911, the congregation constructed a new church at 8907 Holton Avenue, thereby becoming independent of the German Church.

The Hungarian Baptist Seminary was initiated around the time of the founding of the mission to prepare young men for the Hungarian Baptist ministry. In 1920, eleven men were enrolled in the four year course of study.[26] Reverend Orosz served as Dean of the Seminary.

The congregation lent aid and support to other missions, including: the North West Virginia Mission, the West Side Mission (Cleveland), the Mission in Barberton, Ohio and the Buckeye Road Mission (East 118th Street). In addition, their efforts assisted in the organization of the Youngstown, Ohio Mission.

During the pastorate of Reverend Orosz, which lasted until 1920, membership rose to 242. Reverend Orosz was followed by Reverend Michael Biró, who guided the congregation through the Great Depression. Dr. Charles Gruber became pastor in 1937. In 1948, the Holton Avenue and Buckeye Road Churches were unified, forming the Shaker Square Hungarian Baptist Church, which relocated to 2844 East 130th Street. Dr. Gruber took a leave of absence due to illness in 1948, and was replaced by Reverend Emil Bretz. In 1957, Reverend Bretz introduced a bilingual preaching service (English-Hungarian) in order to accommodate the ever increasing number of second and third generation members. Presently, Reverend Edward Orosz, son of Reverend Stephen Orosz serves as pastor of the church.

Jewish Temples

The first Hungarian Jewish congregation, B’nai Jeshurum, was organized in 1866 by Herman Sampliner with an initial group of sixteen meeting at the homes of individual members. As membership increased, public halls were rented to accommodate the congregation and visitors on the great Holy Days. The first rabbi was Morris Klein, who officiated from 1875-1886. Halle’s Hall on Superior Avenue and the Anshe Chesed Synagogue on Eagle Street served as temporary homes of the congregation. A new temple, dedicated on September 16, 1906, was constructed at the corner of East 55th Street and Scovill Avenue. By that time the congregation had grown to 454 members.

Originally founded as an orthodox congregation, B’nai Jeshurum became increasingly liberal in the 1900s. Dissident groups formed offshoot congregations, such as the Oheb Zedek congregation. In 1922, the temple at East 55th Street and Scovill Avenue was sold and the congregation moved to a new location at Lee Road and Mayfield in Cleveland Heights.

The Oheb Zedek Hungarian Jewish congregation was organized as an orthodox offshoot of B’nai Jeshurum in 1904. The congregation constructed a temple at Parkwood Drive and Morrison Avenue in Glenville and purchased land to be used as a cemetery. By 1920, the membership had grown to 300. One of the founders of the new congregation, Dr. H.A. Liebowitz, wrote the first history of the Cleveland Hungarians.

Shomre Hadath originated with the formation of a “minion” (religious requirement of ten adult males for organized prayer) in 1922. The congregation’s first permanent synagogue, constructed in 1926, was located at East 123rd Street and Parkhill Avenue. The membership organized a Sunday School after completing the construction of the new synagogue. A women’s auxiliary was founded to raise financial support. A burial society, the Chevre Kadisha, was established to assure members of an orthodox burial rite. In the early 1970s, due to dwindling membership, the temple was sold. Many of the younger generation left the orthodox traditions of Shomre Hadath in favor of more reformed practices. In addition, a large majority of the membership relocated in the suburbs of Cleveland and joined other temples, such as the Temple on the Heights.

E. CULTURE, LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE

Hungarians in Cleveland were organizing dramatic presentations and choirs before a definite community structure evolved. In 1891, Ferenc Apáthy organized the First Hungarian Dramatic Society. The first choir was founded in 1892 by Béla Olchváry. By 1910, nearly a dozen Hungarian cultural and civic organizations were active in Cleveland. The success and growth rate of these cultural organizations, established both on the east side (Buckeye Road) and the west side (Lorain Avenue) was phenomenal. Many of these organizations, fostering the arts, drama and sports since the early days of Hungarian community life in Cleveland, continue in this tradition to the present time.

The first large-scale theater production, “János Vitéz” was presented by the Cleveland Hungarian Self-Culture Society in 1906. It was a phenomenal success. In the following years, the number of locally-sponsored presentations continually increased, providing culture and entertainment for Hungarian audiences. Later, a professional theater company was founded in Cleveland by Sándor Palásthy; their first performance took place in 1914. By the early 1920s, “Sándor Palásthy’s theatre group consisted of 25 professional actors, an orchestra and a large managerial staff; it regularly toured the larger Hungarian communities between New York and Chicago.”[27]

Hungarians were described by the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1927 as “omnivorous readers,” and the number of Hungarian books drawn from the foreign book section of certain libraries demonstrated that this was in fact true.[28] Rice Public Library, located at East 116th Street and Buckeye Road, acquired over 1,000 Hungarian books to meet the demand. An extensive collection was initiated at the Main Library in downtown Cleveland and at the Carnegie West Branch on Bridge Avenue and Fulton Road. The majority of lodges owned by community organizations housed libraries and reading rooms.

Numerous Hungarian cultural, civic and community service organizations were founded in Cleveland by 1910. The activities of these organizations branched out into many areas: choirs, drama troupes, literary circles as well as football, soccer, basketball and baseball teams. Most of the cultural organization owned lodges which usually housed library facilities, reading rooms and a performing hall with stage. The amateur drama troupes presented stage productions on a regular basis. Constantly improving the caliber of the performances were the combined effects of the competition between the various groups along with the community’s ever increasing support and enthusiasm.

One of the oldest cultural and community service organizations on the east side, the Cleveland Hungarian Young Men’s and Ladies’ Society, was founded in 1891. For several decades, the Society maintained a lodge and library at 11213 Buckeye Road. In 1935, membership was reported at 1,020.

The St. Stephen’s Dramatic Club was established in 1904 under the auspices of the King St. Stephen Catholic Hungarian Society. Initially formed as an amateur dramatic troupe, the members also initiated a choir within a few years. The Club maintained an important role in the cultural life of the community and featured, through large-scale productions, popular theater, operettas, comedy and drama. The presentations were of the highest caliber. The operettas included, on the average, 120 actors and actresses with live music and song.[29] The home and meeting place of the Club, St. Stephen’s Hall, located at 11205 Buckeye Road, still serves as a meeting place for the local Hungarian community. Even as recently as the 1950s, new divisions of the Club were formed, such as a soccer team.

St. John’s Dramatic Club was founded in 1911 by members of St. John’s Greek Catholic Church. The Club produced countless amateur shows, organized educational lectures and maintained a soccer club and a baseball team. Through the years, income from the various functions has been donated to charitable causes. The clubhouse at 11111 Buckeye Road, which houses a separate library, was purchased in 1926.

In addition to the many choirs formed under the auspices of individual organizations, independent choirs were also established. The East Side Hungarian Workers’ Singing Society provided live music and entertainment at community functions, in addition to promoting Hungarian chamber and folk music. Generally, these amateur groups devoted endless hours to practice and their performances evidenced the great time and effort expended.

The Cleveland Hungarian Self-Culture Society was founded on the west side in 1902 by twelve young men for the preservation and promotion of Hungarian culture. The Society sponsored programs featuring the literary works of such writers and poets as: Jókai, Mikszáth, Figyelmessy, Széchenyi, Petofi and Arany. According to the organization’s 30th Anniversary Booklet, they were the first to organize English language instruction for Hungarian immigrants in the city. The classes began in January 1903.

In a short time, a home was purchased at 3829 Lorain Avenue which housed a library, reading rooms, a large hall with a stage, a valuable picture collection and kitchen facilities. The Society’s drama troupe, which eventually earned city-wide fame, sponsored four dramatic presentations annually. American and Hungarian national holidays were commemorated at the clubhouse. The women’s division was established in 1922 with 100 members. Its present home is located on Fulton Road near Lorain.

The Magyar Athletic Club, or M.A.C. was organized in 1908 to serve sports, culture and the community. The membership first met at Olsen Hall and later the German Hall on the west side, until 1917 when they purchased a clubhouse on Vestry Avenue.

The members participated in a variety of different competition matches and from the start, reaped many victories. At a sporting event held in New York in 1918, the club was awarded five silver trophies and several medals.[30] In June 1927, the City of Cleveland organized a competition at which M.A.C. athletes took the top medals in the ten-mile run, the 440 yard dash, the shotput and the high jump. By 1930, a football, basketball, wrestling and boxing division were active. These activities were halted, however, by the depression.

The West Side Hungarian Workers’ Singing Society, established in 1908, earned a reputation as one of the most active Hungarian organizations in Cleveland. In 1911, a clubhouse and hall was constructed at 4309 Lorain Avenue, to serve as a permanent home for the Singing Society. The annual concerts in addition to the numerous plays and operettas presented by the group became increasingly popular during the 1920s and 1930s. The Society produced radio shows and performed at park festivals and parades. In 1938, membership was reported at 100 singers, with forty-six supporting members.[31]

Mrs. Helen Horváth (nee Zalaváry) was a renowned social activist who was determined to assist immigrants in the difficult and many times painful adjustment to life in America. Mrs. Horváth came to Cleveland in 1897. One of Helen Horváth’s experiences as a newcomer to this city was something which hundreds of immigrants before her and thousands after her also experienced: the intolerance of more established Americans towards the immigrants’ accent, mode of dress, etc. Mrs. Horváth went into a dry goods store intending to buy braid, however, instead of braid the store clerk understood her to have said “bread”. The clerk had a good laugh, thereby attracting other customers and clerks around her, and told them all that this woman had asked for bread, why then didn’t she go to a bakery? Mrs. Horváth determinedly went to the counter where the braid was and made it clear what she wanted.[32] Afterwards, however, she made herself a promise that she would not suffer such humiliation again. Horváth studied the English language until even her pronunciation was impeccable and initiated classes for the foreign-born to assist others in attaining a working knowledge of the English language and American ways.

Helen Horváth opened her first school in 1901. The first classes were held specifically for Hungarians, however, within a few years her work encompassed nearly all immigrant groups. Mrs. Horváth’s motto: “Speak United States” embodied the philosophy of her work. While emphasizing never to forget one’s own culture, she transformed bewildered and isolated immigrants into self-confident individuals with a greater understanding of American culture. The opening of the first school became a landmark year in the history of adult education in Cleveland.

For nearly thirteen years Mrs. Horváth worked alone and unrecognized. The advent of the First World War altered this situation, however, as fear of the foreigners heightened and the gap between established Clevelanders and the immigrant population became more pronounced. Adult education classes for the foreign-born in Cleveland were virtually non-existent, except for the work directed by this lone Hungarian woman. Suddenly realizing the importance of her work, the Cleveland Board of Education invited Mrs. Horváth to join the city school system with her already established schools and authorized her to open new schools and expand the existing programs.

The trailblazing work of Helen Horváth proved to be of invaluable service to the City of Cleveland at this time, substituting education and understanding where only distrust and fear had existed before. Not only did her work provide a comprehensive course of study for immigrants, she was also requested on frequent occasions to organize Hungarian-American cultural exchange programs.

In 1928-29 Helen Horváth was requested to organize Hungarian concerts under the direction of the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra. For five years a Hungarian Forum was conducted by Horváth at the request of the city. In addition to all these activities, she served as founder and first President of the Cleveland Chapter of Pro-Hungaria, a world-wide Hungarian women’s association organized for the preservation and promotion of Hungarian culture. Through this organization, countless cultural programs were presented, the majority of them being presented in English and open to the general public.

In addition to “Speak United States,” Helen Horváth also advocated the concept of “See United States.” Each year, starting in 1925, she organized tours to Washington, D.C. for her students and anyone else who was interested. As an immigrant herself, Mrs. Horváth believed all Americans and all immigrants who are thinking of becoming U.S. citizens should experience the nation’s capital.

The tours expanded and gained considerable prestige through the years. In 1926, Mrs. Calvin Coolidge received the members of the tour at the White House. Following that occasion, the Horváth Educational Tours were regularly received by other First Ladies, including: Mrs. Herbert Hoover and Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt. The countless gifts of Hungarian art, embroidery and unique books presented to the First Ladies by members of the tour enhanced the interior of the White House for generations. Horváth Educational Tours were also conducted to California, Yellowstone Park, Estes Park (Colorado) and even to Alaska.

Helen Horváth was the recipient of numerous honors and awards in her lifetime. Her portrait is displayed at Carnegie West Library in Cleveland, where she initiated the famed School for Mothers and where, due to her efforts, a large Hungarian collection is still maintained. In 1929, the Hungarian government bestowed her with the Order of the Red Cross for her efforts in helping to ease the post-World War I sufferings in Hungary. Helen Horváth contributed significantly to the development of adult education for the foreign-born in Cleveland. She proved to successive generations that being an immigrant and a woman are not necessarily handicaps, if one is truly committed to a goal.

After twenty years as founder and editor of Szabadság, Tihamér Kohányi wrote:

I am tired my friend, terribly, mortally tired… Twenty years is an immense amount of time and during these twenty years I have worked, toiled and suffered to such extent, as I would have never worked or toiled had I remained with my first occupation in America, as a mine worker, shoveling coal… I tell you that if one is truly cursed by fate, he will become a Hungarian-American newspaper journalist.[33]

The life of Kohányi was indeed uphill work; he succeeded in establishing a Hungarian daily which was a self-supporting business enterprise with an entire staff of workers. In order to accomplish this, however, he went without income, a home and family life. Often, he didn’t even know where his next meal was coming from. The pace with which he kept the newspaper going eventually hastened his death.

Generally, Hungarian immigrant journalists, writers, poets, and novelists had difficulties, to say the least, in supporting themselves. Often the unfortunate individual, whether talented or not, toiled in a factory by day and wrote by night. Szabadság alleviated this situation to some extent by hiring a number of them; this was the only means by which many survived in America. Despite the hardships, countless Hungarian-language newspapers were founded in Cleveland. Numerous novelists and poets succeeded in publishing their works.

The Képes Világlap (Illustrated World Review) was founded in 1915. The first illustrated literary and news weekly, it was edited by John Biro. Árpád Tarnóczy, lyricist, arrived in America in 1911. Tarnóczy was editor and founder of several Cleveland-based newspapers, including: Bukfenc (Topsy-Turvy), a humorous paper and Mákvirág (Poppyseed Flower), a literary magazine. Gyorgy Kemény, an epic poet who immigrated to the United States in 1896, edited Dongo (The Buzz). Following the First World War, two Americanization newspapers came into existence: Amerika, published in Hungarian by Dr. László Pólya and Speak English, edited by Dr. Arthur Winter and Dr. Joseph Reményi. These newspapers were extensions of a large-scale program promoting the rapid assimilation of ethnic immigrant groups living in the United States.

László Pólya was a renowned poet who wandered from place to place, never settling down anywhere for long. Pólya authored several books of poetry; of these My Pipe was published in Cleveland in 1937. Louis Linek was a famous caricaturist whose drawings and cartoons are widely distributed in various issues of the Szabadság. Linek also painted portraits and/or caricatures of celebrated Hungarian-Americans.

Hungarian immigrant novelists included: Julius Deri and Stephen Linek. Ferenc Bizonfy compiled the first Hungarian-English dictionary published in the United States. Géza Kende authored the first extensive history of Hungarians in America; the two-volume text was published by Szabadság in 1927. Another researcher of Hungarian-American history was John Korosfoy.

Joseph Reményi, novelist, poet and essayist arrived in America in 1914, after receiving a Ph.D. in comparative literature in Szeged, Hungary. In Cleveland, he was first employed as a social investigator by the Cleveland Foundation and later was a journalist for the Szabadság. Reményi was appointed to the Chair of Comparative World Literature at Western Reserve University in 1929. Through this position, he became known as “an apostle of literature,” who emphasized literature as the key to international understanding.[34]

During his lifetime, Reményi published over seventy essays and dozens of books in English and Hungarian, advancing considerably the cultural exchange between the two nations. His contribution as professor of the only comparative literature class in the City of Cleveland was significant. (There were only about a dozen comparative literature courses being taught in the United States at this time.) He was first in America to give literature courses on television. In addition to countless awards and honors bestowed upon him by American and Hungarian literary and scientific associations, Reményi was elected to membership of the International Academy of Literature and Science in Paris.

Joseph Reményi compiled anthologies of Hungarian literature was called upon frequently to contribute Hungarian sections in world anthologies published in the United States. His numerous publications and essays enhanced the knowledge of Hungarian literature in the English-speaking world, introducing the works of such writers and poets as: Dezso Kosztolányi, Mihály Babits, Attila József, Ferenc Molnár, László Németh, and Sándor Petofi.