Section I: History of Hungary

The Twentieth Century

Hungary was involved in the events of World War One from the beginning as part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and an ally of Germany. Hungary’s Minister President, Istvan Tisza protested on several occasions the declaration of war by the Austro-Hungarian Empire on Serbia. Because foreign affairs and defense were common with Austria, Hungary found herself embroiled in a devastating world conflict which ultimately led to the dissolution of the Dual Monarchy and, of more grievous consequence, to the partitioning of Hungary.

During the exhaustive four year war, Hungary suffered the loss of 661,000 soldiers or well over one-half million, with casualties and soldiers taken prisoner amounting to around one and one-half million. At home, war weariness and short food supplies caused widespread social unrest. Political change was imminent. On October 25, 1918, Count Míhaly Károlyi, leader of the Social Democratic Party set up a National Council in Budapest. The platform of the new government was to sever ties with Austria and Germany, conclude a separate peace with the Allies, introduce social and political reforms and make the necessary concessions to Hungary’s minorities. Karolyi was appointed Minister President and in November of that year Hungary was officially proclaimed a republic.

The new government set out to implement the proposed reforms, however, several factors hindered progress. First of all, agreements made between Hungary’s neighbors and the French resulted in the unlawful occupation of northern, southern and eastern Hungary by Czech, Serb and Rumanian forces, respectively. Towards the end of the war, several successor states were created out of territories partitioned from Hungary. Occupation of these territories was already underway in 1918. This occurred prior to any treaty signing, with the full knowledge of the Allies.

The Hungarian people began to comprehend the intentions of the neighboring states as hundreds of fellow countrymen streamed into central Hungary from the occupied areas. The inner stability of the country steadily deteriorated. Extremist agitators, led by the communist Béla Kun, gained control of the government and declared a “dictatorship of the proletariat” on March 21, 1919.

The new revolutionary government made one mistake after another, alienating large segments of the populace with drastic measures, such as nationalizing agriculture instead of distributing the land. Red terror was widespread. The communist government was further unable to halt the unlawful occupation of territorial Hungary. The Rumanians took advantage of the inner turmoil of the country by occupying much of the central plains area, terrorizing the population and looting with great thoroughness. Kun’s government fell less than five months after assuming power, in August 1919. It was replaced by an anti-bolshevik provisional government formed in Szeged under the leadership of Admiral Nicholas Horthy, onetime Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial and Royal Adriatic Fleet.

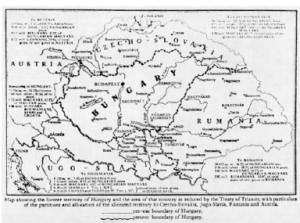

Four years of exhausting war, two violent revolutions and a predatory foreign occupation were compounded by the peace treaty dictated to Hungary on June 4, 1920. The Treaty of Trianon forced Hungary to give up 71% of her historic territory and 63% of her population. The losses in natural resources and industry were staggering. Some examples of the losses included: 61% of arable land, 88% of timber, 62% of railroads, 83% of pig iron output, 55% of industrial plants and the entire gold, silver, copper and salt deposits. The greatest tragedy, however, was the loss of one-third of the entire Magyar population living in the detached areas. More than one million Hungarians were transferred to the new Czechoslovak state, nearly two million were placed under Rumanian rule, 500,000 were attached to Yugoslavia and 24,000 to Austria.

This was accomplished in the name of self-determination. The Hungarian delegation was not allowed to present its case or refute the gross allegations made against them at the drafting of the treaty. The most important parties involved, the people residing in the partitioned areas, were given no say in the matter, no plebiscite was ever held. The leaders of the successor states determined the new borders to their own territorial advantage, often detaching solid Magyar areas from Hungary.

The dismembered country, stripped of most of her natural resources and industry, experienced soaring inflation and unemployment. Further problems were created by the thousands of Magyar refugees fleeing from the occupied territories to the mother country. By the end of 1920, close to 400,000 Magyars fled or were expelled-a distinction which was often without difference. These refugees added to Hungary’s phenomenal problems. They lived under pitiful conditions, many families making temporary homes in boxcars or freight cars.

In March 1920 the first post-war national assembly elected Nicholas Horthy regent and acting head of state, reestablished the constitution of the Kingdom of Hungary and severed all connections with the Hapsburg dynasty. Horthy’s regency spanned the entire inter-war period until 1944, when the Germans occupied Hungary and established their own puppet regime.

Hungary’s bitter experiences of the First World War and its aftermath warned against any entanglements with either of her two overbearing neighbors, Germany or Russia. Reflecting this, the inter-war period was characterized most of all by an all-encompassing attitude of conservatism on the part of the ruling political elite. One aspect of this conservatism was that social progress was stifled. A class society based on birth, ancestry, kinship and wealth continued to exist. Urgently needed land reform laws—distributing land to the peasantry—were not acted upon.

Conversely, the conservatism of this era was one of the factors which maintained Hungary’s relative independence during the war. To illustrate, the Hungarian Arrow Cross Party never gained power through legitimate means; it was only after the German army occupied Hungary in 1944 that they obtained control. During the prime ministership of Miklos Kallay (March 1942–March 1944) “Hungary’s Jews were afforded a protection then unparalleled on the continent.” Following the collapse of Poland, Hungary made possible the escape of 50,000 Polish soldiers to the west and gave refuge to 30,000 Polish Jews, many of whom were given Christian papers by the Ministry of Interior.

The revision of the Treaty of Trianon was of primary importance to the government during the inter-war years. Surrounded by unfriendly successor states partitioned from her territories, Hungary sought to align herself with western nations who would lend assistance in rectifying the injustices of the treaty. Hungary’s overtures to the west were received with mild indifference. The United States, the only country which never signed the treaty, retreated from European involvement. France supported the Little Entente and was primarily responsible for the creation of the successor states. Adding further to Hungary’s insecurity was the collapse of Poland, German successes in the west and Rumania’s entrance into the war on the side of Nazi Germany.

Hungary’s revisionary aims were satisfied in part by Germany through the First Vienna Award (1938) and the Second Vienna Award (1940), whereby territories of southern Czechoslovakia and western Rumania (Transylvania) containing large Magyar populations were returned to Hungary. Following the Vienna Awards, Hungary was obligated to enter into wars with Germany’s enemies; first with Yugoslavia in April 1941 and secondly with the Soviet Union in June 1941. One of Hungary’s most distinguished statesmen, Prime Minister Paul Teleki, committed suicide when he was unable to prevent the transit of German troops through Hungary and collaboration against Yugoslavia.

On several occasions during the war, Hungary contacted England and the west to negotiate for a surrender. Overall these attempts were unsuccessful, particularly after Yalta when Hungary was assigned to the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence. In October 1944 Hungary signed an armistice with the Soviet Union, after which Hitler directed the complete military take-over of Hungary and brought the Hungarian Arrow Cross Party to power. During the five months reign of terror of the Szálasi Regime, many executions and deportations were carried out, affecting Hungarian Jews and all civilians resisting in any way the Nazi take-over.

In 1945 Hungary’s misfortunes were compounded by the “liberation.” According to estimates, as many as 200,000 Russian soldiers were permitted to desert, creating a general state of lawlessness and wanton destruction. The “liberators” committed deplorable acts of violence against the defenseless civilian population: looting, rape and murder were commonplace and for several months afterwards chaos prevailed.

In the first post-war elections held in 1945, the Smallholders Party won the majority with 57%, while the Communist Party gained only 17% of the vote. Two years later, despite all efforts to improve their popularity, the communists could still only muster 22% of the vote. The Hungarian National Independence Front, or Communist Party, then proceeded to liquidate all other political parties, either by eliminating them or absorbing them. The one party, one ballot election followed; voting became obligatory. The final confrontation took place within the party itself. The homegrown or national communists were replaced by communists from Russia who were Hungarian in name only.

By 1948 all opposition parties had been liquidated. A “Monolithic Dictatorship of the Proletariat” was declared, which later became known as the “Rákosi System,” led by Mátyás Rákosi. It was a faithful replica of the Stalinist system in the Soviet Union. Measures were instituted through which individual freedoms—of speech, press and of religion—were summarily abrogated. Pre-war estimates of the number of people in Hungary’s prisons range from 4,000 to 6,000. In contrast, during the post-liberation years (1945–1956) an unbelievable 60,000 to 70,000 people were incarcerated. The Hungarian secret police (A.V.O.) was the most terrifying branch of the government, its network spanned the entire country; no occupation, profession or place of employment was exempt from its scrutiny. One out of every five families in Hungary had contact with the dreaded secret police.

The death of Stalin in 1953 signalled a change in the Soviet Bloc countries, most significantly, a gradual relaxation of controls took place. The Kremlin reproved Rákosi for economic mismanagement and for alienating the masses. He was replaced as prime minister in 1953 by Imre Nagy, a reform-minded Hungarian communist. Limited criticism of the policies of government were tolerated, notably the writers through the Irodalmi Újság (the organ of the writers’ union) and the students of the Petofi Circle took the opportunity to criticize censorship and the lack of personal freedoms.

Rákosi was again returned to power in 1955, at which time he attempted to regain absolute control. This backfired, however, and on October 23, 1956 a revolution erupted in Hungary led by students and workers. Revolutionary councils were formed all over the country; their major demands included: withdrawal of Soviet troops, political and economic equality relations between the Soviet Union and Hungary, revision of the economy, democratization, changes in government organization and personnel, dissolution of the security police, protection of those taking part in the revolution, withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact, Hungarian neutrality, a call for free elections, free speech, press, assembly and worship.

During the brief but momentous revolution, the Hungarians succeeded in driving the Russians out of their homeland. The revolutionaries demanded a new government under the leadership of Imre Nagy. Nagy began negotiations with Moscow for total troop withdrawal and declared Hungary’s neutrality. Withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact was declared and assistance was requested from the United Nations.

On November 4th Soviet troops invaded Hungary and crushed the revolt. Imre Nagy was arrested, along with other leaders of the revolutionary council. A new “Hungarian Revolutionary Worker-Peasant government” was announced under the leadership of János Kádár. Although the fighting ceased, general strikes continued for months afterwards.

The casualties of the thirteen day revolution were staggering. Over 25,000 Hungarians died in the fighting, 400-500 were executed and an estimated 40,000 were imprisoned or deported to Siberian labor camps. Two hundred thousand Hungarians fled to the west, or nearly two percent of the nation’s population. They were mainly the young and oftentimes the elite of the nation.

Hungary has undergone dramatic changes since the Revolution of 1956. Many historians have assessed the ultimate success of the uprising in the relative prosperity and freedom allowed Hungary by the Soviets in the 1960s and ’70s. János Kádár has led the Hungarian communist government since the aftermath of the revolution and under his leadership the country has become a model of sorts among the Soviet Bloc nations.

During the past two decades, Hungary has experienced rapid industrialization, modernization and urbanization. Living conditions have improved considerably. Political pressures have been reduced; this change was signalled by the abolishment of the notorious people’s court, the scene of many show trials during the 1950s. Although Soviet economic exploitation of the country is still prevalent, individual and national incomes have increased substantially.

The most noticeable advances made in recent decades have been in the areas of social welfare and education. A class society which was still entrenched in the social order of inter-war Hungary has disappeared. The social stratification which does exist is based on occupation and education rather than birth. Moreover, there is a significant amount of social mobility.

Overall, the social welfare system of Hungary has proven relatively successful. In particular, the family allowance system is unique among socialist countries as well as in many parts of the world. It was inaugurated in 1969 in response to Hungary’s rapidly declining rate of birth. The program includes maternity grants for all expectant mothers and mothers of young children. Over 97% of the population is covered by the social insurance system which provides an overall health and drug program. The present day Hungarian educational system has provided the masses with quality education-from nursery school through secondary institutions of learning. Rural as well as urban children have access to a good education.

The presence of Russian troops in Hungary, however, severely limits the freedom of the government and the nation. According to estimates published in the 1970s, there are between 60,000 and 70,000 Russian troops permanently stationed in Hungary, constituting two armored divisions and two divisions of motorized infantry. The Hungarian government has no independence in matters of external affairs and even in many areas of economic and political development, the Soviet Union determines official policy.

The Hungarian government is further not permitted to recognize the Hungarian minorities of Rumania, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia or conduct any cultural exchange with these groups. There have been many violations of language minority rights and liberties, particularly on the part of Rumania with regards to the Hungarian minority in that country. The Hungarian minority of Rumania, with a population of three million, comprise the largest minority in all Europe. Unlike the Hungarians living in Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, the Hungarians in Rumania are provided limited access to schooling in their native tongue, employment in their own districts and the chance of upward mobility.The Hungarian minority as well as others, namely Saxons and Jews, have endured an incalculable amount of discrimination under Rumanian rule. The cutback in elementary schools since 1920 serving the minorities in Transylvania demonstrates but one aspect of an overall chauvinistic minorities policy.

| 1913 (Hungarian Rule) | 1931 (Rumanian Rule) | |

| Hunggarian | 2,428 | 248 |

| Rumanian | 2,428 | 3,978 |

| Saxon | 282 | 68 |

| Others (including Jewish) | 58 | 2 |

| Total | 5,052 | 4,296 |

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR FURTHER READING

Dienes, István. The Hungarians Cross the Carpathians. Budapest: (Corvina Publishers). , 1974.

Domján, Joseph. Hungarian Heroes and Legends. Princeton, N.J: (Van Nostrand Co.). 1963.

Kovrig, Bennett. The Hungarian People’s Republic. Baltimore, Md.: (Johns Hopkins Press). , 1970.

Macartney, C.A. Hungary: A Short History. Chicago, Ill.: (Aldine Publishing Co.). , 1962.

Sinor, Denis. History of Hungary. New York: (A. Praeger). , 1959.

Somogyi, Ferenc; and Somogyi, Lél. Faith and Fate. A Short Cultural History of the Hungarian People Through a Millenium. Cleveland, Oh.: (Karpat Publishing Co.). , 1976.

Várdy, Stephen B.; and Kosáry, Domonkos D. History of the Hungarian Nation. Astor Park, Fl.: (Danubian Press, Inc.). , 1969.

Wagner, Francis S. Hungarian Contributions to World Civilization. Center Square, Pa.: (Alpha Publications). , 1977.