Part II: The Irish in Cleveland: One Perspective by Nelson J. Callahan

Chapter 4: Catholicism and the Irish

The Old World Heritage

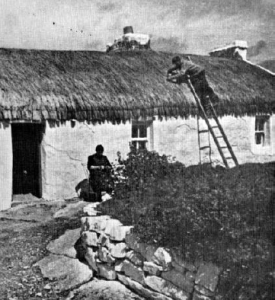

The American tourist who visits Ireland today finds the place remarkably quaint, an odd mixture of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He is also struck almost as soon as he begins to roam around Ireland that the place is very small, not as large as the state of Ohio, 32,595 square miles. Yet Ireland today appears to be very rural; people often gather in small villages at night. But they live on farms, frequently in the often depicted thatched roof cottages, most of which are over two centuries old. If one is Irish in origin, he is aware, as was John F. Kennedy when he visited his family’s home at New Ross in Wexford, that had his family not migrated, he might still be living in such a cottage, working in the fields by day, gathering in the pub by night and moved by the predominant force in the Irish peasant’s life, the Roman Catholic Church, represented by the local parish priest.

This was his tradition, passed on in a tight, clan-like social structure. To deviate from it generally turned one into an outcast with no real alternative in cultural or religious life. Right or wrong, an Irishman was born into a very close community, reinforced by all sorts of social and religious pressures and formed by a tradition in which he placed great pride. Yet this pride, or independence, seems almost ludicrous in the face of the poverty in which, at least by American standards, the Irishman lives today and which surely must have been the starkly real fact of life of his ancestors of a century ago.

Whence came this odd paradox — pride in the face of poverty? To be sure, it came from belonging to an Irish version of the Roman Catholic Church, linked with a special fidelity to the Roman Pope who was seen as an alternative to any form of domination by a temporal king. Added to this was the influence of the climate. The constantly changing sky, the proximity of the sea, and the short life expectancy of the Irish peasant in Ireland made him very much aware of another world, the one he hoped for after death. There he trusted he would become rich in the goods of beatitude. This aspect of the world view of the Irishman in Ireland might be termed the faith component. It may well have been totally incomprehensible to those of the last century who would contempt or oppose him; it could be totally lost by those who do not have that same vision but who so frequently try to write about him today. For example, Leon Uris in his book Trinity.

In any case, to separate Irish culture from Irish Roman Catholicism is to miss the very core of the self-understanding of the Irish immigrant who came to America. It would appear that when he did come here, he valued his Catholicism as his greatest gift. His labor, his wit, his moods, often black moods, were not really factors which he considered ultimately marketable. The preservation of his faith was his top value; and for the most part he kept it during the process of immigration.

Basic Problems of the Irish in America

To be sure there were Irish immigrants who were not Roman Catholics. They came mostly from Ulster and generally arrived in this country prior to the Irish Catholic. These people, Often called Orangemen by the Irish Catholics, were able to merge with the Yankee American Protestants far better than the Irish Catholic who quickly saw the Orangeman here as an enemy far more dangerous than the Orangeman in Ireland. The nineteenth Century saw all kinds of Irish Catholic-Orange Irish hostility, especially in the major urban centers where most of the Irish of both sides settled. But for at least two generations after immigration, the Catholic Irish were virtually without power; the Orangeman often acquired power easily by joining with the Yankees or Wasps with whom he had a cultural affinity both here and in Ireland. In this country, the Roman Church urged the Catholic Irish immigrant to forget the animosities of the old country and to get on with the business of becoming an American. Oddly enough, the Catholic Irish immigrant generally followed this lead of his Church. Occasionally he undertook to aid the cause of freedom for the Irish in Ireland but with no great ardor. Some American Catholic Irish joined in the Fenian cause in 1665 and 1866; more leagued with Charles Stewart Parnell’s Irish League movement in the 1880’s (althogh Parnell himself was a Protestant). But it was the American-born children and grandchildren of the Irish Catholic immigrant who were forced to take sides during the years of the Irish rebellion against England and the creation of Eire between 1916 and 1922. Many supported the Rebellion, a few opposed it, and large numbers remained indifferent or aloof, probably because the Rebellion was against England at a time when the British were the ally of the United States in the First World War. It must have seemed terribly important for many Irish in this country to appear to be almost superpatriots in war lest the accusation by the Yankees, made for nearly 50 years, that the Irish were not good citizens be proven true.

Again, one must cite the policy of the American Catholic Church as the primary promoter of this acculturation; most American bishops struggled to urge their people to acculturate as soon as possible. Thus they hoped to gain respectability for their people, all newly immigrated, so as to overcome the opprobrium often attributed to American Catholics generally who were accused by native Americans as having at best a divided loyalty to the foreign Pope of their religious beliefs and to the American government of their adopted country. American Catholics struggled with this difficult dilemma right up to 1960 when John Kennedy, in his campaign for the Presidency, met with a group of Southern Protestants to answer questions about his loyalty to this country should the Pope order him to do something contrary to the general good of all the American People. Kennedy faced the issue squarely and stated he would regard his oath of office as his highest moral obligation. Al Smith had foundered on the same issue in the 1928 presidential campaign and really never had Kennedy’s opportunity to gain a hearing to explain his position, which was much the same as Kennedy’s.

Without doubt, anti-Catholic and anti-Irish prejudice still existed well into this century and shaped much of the thinking of the Irish immigrant in the last century. On the one hand his bishops were encouraging him to take up the American dream of liberty. Yet on the other hand, the prejudice of the native American often prevented him from moving freely into the mainstream of opportunity in American life.

Cleveland Prior to Irish Immigration

There were few American cities where the story of the frustration and corresponding over-achievement of the Irish Catholic immigrant was enacted with greater drama than in Cleveland. Here the Irish Catholic immigrant’s political heritage (together with his ability to acculturate in the light of this heritage), and the cause of his immigration, came together in a unique way. We shall begin with a look at the background of the city of Cleveland prior to his arrival.

One is struck at once with the fact that Cleveland was part of a strange colonialism in its very origin. In July, 1796, a surveying party of about forty men from Connecticut, headed by General Moses Cleaveland, arrived by canoe at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River with the specific task of surveying the land in Northern Ohio. This land was commonly called the Western Reserve of the State of Connecticut. The surveying party was sent by the Connecticut Land Company, a speculating company of businessmen who had purchased land in what was the Northwest Territory in the State of Ohio. The land had been awarded by the Federal Government for one of two reasons: either to individual citizens of Connecticut to compensate for losses suffered in the Revolutionary War, or given to the State itself to replenish the financial losses suffered by the State in supporting its own army and militia in the war. The land in question included all of Northern Ohio from Pennsylvania’s western boundary to the Cuyahoga River and from Lake Erie south to the forty-first parallel North Latitude. Later this land grant was extended west to the Sandusky River by a purchase of the so-called Firelands by the Land Company, a purchase in total violation of the treaty made by General Cleaveland with the Indians who occupied the area when he first encountered them at Conneaut, Ohio, in 1796.

When the survey was completed by General Cleaveland and his surveyors in October, 1796, they returned to Connecticut, and many of them, General Cleaveland included, never saw Cleveland again. Some members of his company did return the following year, lured by the promise of very inexpensive land offered by the Land Company, which in the winter of 1796-97 set about selling the lots the survey party had laid out.

The hardships, the painfully slow growth and the desolation endured by the early settlers is a story in itself and in many ways has been told before by the wilderness historians, often in romantic terms. The fact was that Wasp people from Connecticut came to Cleveland because they had been enticed by lurid advertising (which bore little resemblance to the reality of the frontier) into purchasing the land, and then had no other choice but to occupy it. So they came west, generally in Conestoga wagons, fearing to trust their belongings to a ship or canoe voyage on treacherous Lake Erie, and grimly determined to make the city of Cleveland prosper. It did, but not until after the lifetimes of the original settlers, who lived short lives and never saw or envisioned what the city of Cleveland was to become.

A study of Cleveland’s history reveals that the city perhaps never would have grown at all had it not been for the theory of covenant the first settlers made with one another, an idea borrowed from The Congregational Church of New England. The early settlers could not go home except in disgrace for failing to keep the covenant. In the case of Cleveland’s early settlers, the covenant was one of money and community as much as of Covenant in Spirit with God and neighbor.

In any case, the settlers stayed, enduring cholera, fever, family tragedy through premature death, dreadful winters, homesickness and separation from the dynamics that were forming the Eastern Seaboard into the United States. However, they were free to organize themselves into a confederation which could apply to Congress for statehood, which they did in 1803. The statehood petition of Ohio was granted that year and ratified by the other states, and thus Ohio joined the Union; The effort in Cleveland was accomplished through great statesmanship by men like Alfred Kelley and Thomas Worthington, and the process of gaining statehood was based on a political device the settlers recalled from their youths on the East Coast, the town meeting.

All of this caused a very tightly-knit Yankee community to become extremely proud of itself, homogeneous and confident in its future in the Connecticut Western Reserve. On the other hand, it all but guaranteed the failure of later non-Yankee arrivals in the Western Reserve to become a part of this community for perhaps the entire remainder of the Nineteenth Century. These facts are important since they provide significant background to understand the several ways in which the Irish immigrants in Cleveland, confronted by the original Yankee community, turned in upon themselves and how these Irish struggled to maintain their ethnicity, or how some failed to preserve any ethnic consciousness, between the years 1845 and 1899.

The Great Famine and the Subsequent Emigration

It seems that just as the recall of the Nazi years in Europe precipitates in Jews everywhere a profound sense of anguish (and rightly so), so the recall of the Great Famine in Ireland between the years 1845 and 1853 produces a similar anguish in Irish people even to this day, allowing of course for the fact that the details of this catastrophe are dulled both by time and by some romanticism. One hesitates to pause for any length of time to describe the Famine, but at the same time it must be noted that it was the sole and pivotal cause of Irish immigration to the United States in the middle of the last century.

There were some Irish who had come to this country in the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Some of them were Catholics but very few. The English Penal Laws for Irish Catholics, which were not abrogated until 1829, all put precluded the Catholic Irish from even thinking about such a violent break with their past, bad as that past was. Moreover, the traditional clanishness of the Irish family made the prospect of emigrating even less likely. There were laborers who came here In the 1820’s to work on the canals of Ohio, but they came from Belfast. Many of these people had been drafted by the English from the poor in the South of Ireland to work on the channels of Belfast. Once these were dug, they were free to return to the poverty from which they had come, or to emigrate from Belfast to work on the canals in America. Some did emigrate, only to find that the fevers and the inhuman conditions with which the canal workers lived in Ohio brought them an early death.

Cemeteries along the Ohio Canal at places like Peninsula reveal the marked graves of a few of these men; most of them, however, were buried in unmarked graves. They seldom married, they had no time for courting, and there are few descendants here today who can trace their roots back to these early Irish Catholic canal workers. Their story is basically a tragedy about which, except for the research of William Hickey, has yet to be written.

It was a different thing with the Famine Irish. They were free to emigrate if they could raise the money to do so. The pattern of their stories was much the same for all. They were driven by a sense of desperation and a very real fear that the very tight family, deprived of its livelihood by a suddenly unproductive land, might become extinct. They did not particularly want to leave Ireland; they knew little, if anything, about America other than the hope that it might allow them to survive. No other immigrant group came to this Country moved by such a crisis and with such reluctance than did the Famine Irish.

Statistics perhaps tell the story best. There were over eight million people living in Ireland in 1845; by 1853 there were five million people living in Ireland. Eighty-five percent of those who left Ireland listed their place of designation as the United States. In the subsequent half century, another three million Irish came to America although it is true that in the Famine years more Germans came to the United States than Irish, for every German who came here, 33 remained at home. The unique thing about the Irish emigration is that during a fifty-year period one of every five people emigrated.

This massive flow of Irish immigrants to America had special characteristics. Most of the people who left were young, usually between age fifteen and thirty-five. Thus the very young and the elderly were left behind, hoping that the emigrant would earn enough money in his first year here to bring the rest of the family out to America. There was a certain urgency in ail of this. In the presence of the Famine, a family generally liquidated all its assets, and sent out its strongest member who had the burden of finding and keeping a job in America. He, or often she, was expected to earn enough money to bring the rest of his family to this country within a year. The time limit was important since there was very little left for the family in Ireland to live on once it had sold all its possessions. Most families could not last much more than a year without starving. This procedure placed a great burden on the one chosen to go to America first. Often enough, he or she failed. Sometimes the problem was an inability to get a job; sometimes money earned to be sent back to Ireland was squandered on alcohol, and sometimes illness precluded any saving of money. As a result, families waiting in Ireland died, and the quilt of the first immigrant was so overwhelming that the immigrant was rendered useless in his new country, which was hardly the land of milk and honey about which he had dreamed.

The voyage to the United States on the Cunard Sailing Ships for the Famine Irish was of special importance. The conditions on these ships were the worst encountered by any immigrant group. The whole ordeal cost $37 in steerage. The immigrant was expected to bring enough food to last the six weeks journey from Queenstown to New York, Boston, Philadelphia or Montreal. He was to buy fresh water, when it was available, from the ship’s captain. He was allowed only two hours a day on deck. Worst of all, in the steerage of these ships, deadly and contagious diseases often sprung up; sometimes only one in ten survived the voyage. The survivors landed here ill and feeble, hardly able to begin the backbreaking work which was all that was available to them in their new-found land.

Arriving in Cleveland

By 1848 the Famine Irish knew that there was no place for them at the ports of arrival on the Eastern Seaboard, so they began to drift inland looking for the jobs on the frontier that would sustain them. They worked on the railroad being built from New York to Chicago by Commodore Vanderbilt. They stopped in cities such as Cleveland, Chicago, Pittsburgh and even St. Louis, to settle down to do the laboring jobs which were opening up in these places. In these cities the Irishman’s labor was wanted; his presence was not wanted.

Cleveland was such a city. In 1855 the Locks at St. Marie were opened and the city suddenly became a boom town. Iron ore could be cheaply brought to the docks on the Cuyahoga River where it was processed into steel. Strong men were needed desperately to unload the ore boats (by wheelbarrow), which were arriving daily at the docks; even stronger men were needed to work in the steel mills, which in 1855 were located in Newburgh, south of Cleveland. The jobs in these places fell to the Irish immigrants, the least skilled of all European peoples. Thus the early Irish settlements were located near the docks on the near West Side; here they formed St. Patrick Parish on Bridge Avenue in 1853. Or the Irish settled near the steel mills in Newburgh where they formed the parish of The Holy Name in 1854.

Thus, the early Irish immigrants in Cleveland were already twice displaced. They had found no room and no opportunity for work at the cities on the Eastern Seaboard where they had first tried to settle. It became clear to them very quickly that the jobs were in the rapidly developing Midwest. Raw physical labor was the primary requisite, and this gift they were willing and able to trade on the open market for the opportunity to work.

They probably got here on the railroad, sometimes by helping to lay tracks for the New York Central which came through Cleveland in 1849. In any case, the vast majority who settled in Cleveland stayed. But in Cleveland, the Irish who were Catholic found a situation which resembled to a remarkable degree the same caste system they had known and fled from in Ireland. They had jobs, but there was little chance of upward mobility, mostly because of their lack of skills and their own lawlessness. Moreover, at the top of the system were the Yankees who recalled for the Irish the landlords from whom they had sought to escape in Ireland and whom the Irish firmly believed were close kin to the people who had oppressed them for close to two centuries in Ireland.

For their part, the third generation Yankees or Wasps or whatever one chooses to call them, saw in the arrival of the Irish, to Cleveland the beginning of a vast threat to their American enclave. Perhaps no city in the United States had its serenity broken as violently as did Cleveland by the first Irish immigrants. The disparity between these newly arrived immigrants and the native American was dramatic.

The Irish were at least culturally Roman Catholic; the native Clevelanders were not, and feared greatly the possibility of a segment of the people being dominated by the Papal States, the Church of Rome, and its Pope.

The Irish had no skills, were total strangers to the developing industrial revolution, and were generally illiterate, although they spoke the English language. This latter fact was to their advantage over later immigrants, but to their disadvantage with the native Americans who were bewildered to find people who spoke English well but who could not read nor write it, and who apparently never comprehended that it was their ancestors in England who had promoted illiteracy in Ireland.

The Irish were the first large group of immigrants who were not Wasps to arrive in Cleveland. Thus, neither they nor the native Americans had any previous memory of patterns of acculturation in which they could find hope of becoming “like us” or “like them,” depending on one’s point of view.

The Famine Irish in Cleveland were at first remarkably unruly. It has been stated in the Cleveland Leader, a notoriously arti-Irish newspaper, that between 1850 and 1870, 90% of the violent crimes in Cleveland were done by Irish.

The Irish had no previous experience with representative government, orderly town meetings or consensus in decision making, and yet they were given the vote with little preparation or knowledge of issues. The native Americans saw the Irish voting power and the Irish reputation for revolutionary tactics in the presence of tyranny in Ireland as a positive threat to the whole system of state and national political life.

The immigrant Irish found, when they arrived in Cleveland, no organized societies of their kinsmen to welcome them, nor were there any agencies which could even help them think through the trauma of immigration. Nearly all ethnic groups that arrived in Cleveland after the Irish found such agencies or organizations.

The voyage across the sea all by itself had to be an event loaded with fear and risk. Babies were born aboard ship, mothers and fathers died aboard ship, and the whole event for each of the survivors became an experience one never spoke of once in America. It was hardly the passage for which the immigrant might have hoped, and by the time he arrived in Cleveland he surely must have wondered whether the whole attempt at making a new life was worth it. The native Americans understood none of this and were genuinely puzzled at the total rootlessness and consequent psychological disorientation of the Irish immigrant.

Due to the laws of Catholic suppression, most Irish immigrants had never been able to own property in Ireland. At first they saw no value whatever to owning property in Cleveland, hence their instability in the city. Also, because of the Famine, they generally refused to settle on farmland, which was often almost free to the Germans who had arrived in the Western Reserve as early as 1848. For the native American, ownership of land and the frugal management of it were central values, and indeed virtues.

Without making any attempt to excuse the fact, it must be admitted that the Famine Irish arriving in Cleveland (and perhaps many Irishmen descended from them) had a serious problem, either real or potential, with the abuse of alcohol, which in 1847 in Cleveland was easily as cheap as water. For the descendant of the Puritan living in Cleveland at that same time, sobriety was one of his most cherished virtues. For him, any lack of sobriety among the Irish was much more than a troublesome annoyance; it was a sin which he simply could not tolerate. And thus did the Famine Irish encounter the native American, rooted in New England Puritanism, in Cleveland.

Early Irish Settlements in Cleveland

And what happened? Power was in the hands of the nativeborn American in Cleveland. His reaction to the Irish immigrant followed several somewhat predictable stages, First, he generally withdrew altogether from any part of “his” city in which the Irish settled. Thus he consigned to the Irish territory which he had once felt was his own, or areas which had previously been uninhabitable. On the West Side he gave the Irish the territory near the Cuyahoga River, including a peninsula running along the shore of Lake Erie which the Indians a half century earlier had abandoned because of its fever breeding swamps. It was called Whiskey Island, and it soon became a major shantytown, honeycombed with saloons and infested with prostitutes. Next the Irish were given the west side of the Cuyahoga River bluffs and there built a ghetto of tar paper shacks, pictures of which still exist in Cleveland’s Main Library. This area was called Irishtown Bend. And on the East Side of the river, where the mercantile city was beginning to bloom, the Irish were forced into ghettos along the shore of the lake or in the swampland north of what is today the financial center of the city but what was in the 1840’s and 1850’s considered out of town, east of East 9th (or Erie) street and north of Superior Avenue. In 1845 the area was generally considered unhealthy. It too was mostly swamp.

These areas of Irish settlement became so densely populated that they had to be noticed by the native Americans of Cleveland, and indeed they were noticed, the newspapers of the day gave a graphic picture of the scene, condemning the squalor, crime and general lack of good citizenship displayed by the Irish. There was, however, no effort to help the new immigrants and no sympathy evidenced for their plight: there were no organized programs of public health, sanitation, adequate housing, job opportunity or even any hope on the part of the native Americans of Cleveland that the immigrant Irish might ever become useful citizens of their new land and city. Quite the contrary was true. Political forces already in motion in other cities of the country, in the form of the Nativist American Movement, came alive in Cleveland, and all sorts of laws which have been well described by Carleton Beals in his book The Brass Knuckle Crusade became part of the legal and punitive system in Cleveland. The immigrant Irish responded with more violence and with a deep interior hopelessness.

Development of the Catholic Diocese of Cleveland

Then a vastly significant, and for the immigrant Irish, a providential event took place which was, this writer believes, to ultimately shape their whole destiny in Cleveland.

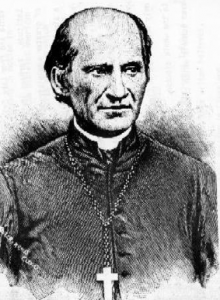

Far away in Rome on April 9, 1847, Pope Pius IX, at the request of John Purcell, Bishop of the Diocese of Cincinnati, which up to that time embraced all of the State of Ohio, divided the Cincinnati Diocese and created the new Roman Catholic Diocese of Cleveland. To be bishop of this new diocese, the Pope named Father Amadeus Rappe, a French-born missionary priest who had come to work on the Ohio Mission in 1840 at the request of Bishop Purcell, and who had been laboring among the struggling Irish workers in the Toledo area. They were engaged in digging the new canal connecting the Wabash River in Indiana with the Maumee River near Toledo, and among them, because of his special concern for the problems of the Irish, Rappe had developed a good reputation.

The new Diocese of Cleveland extended from Indiana to Pennsylvania and from Lake Erie south to the fortieth parallel of North Latitude. Perhaps in retrospect, Rome might have chosen a man of greater administrative ability, but Rappe was a good man, a simple priest of the people, and was remarkably aware of the needs of his people. When he came to Cleveland to take possession of his See he found seventeen churches in the whole diocese, only one of which was in Cleveland, Saint Mary’s of the Flats on Columbus Road at Girard Street (demolished in 1886); he found only one priest in Cleveland, and less than twenty-five priests in the whole diocese. There were no Catholic institutions, not even schools which could be called parochial.

As soon as he got to Cleveland, however, the new bishop began a remarkable building program which was, at first, designed to aid the most urgent needs of his Irish people. In Cleveland alone during his first ten years as bishop, Rappe, with the help of money he collected in France:

- Built a new Cathedral to replace Saint Mary’s. It was located at East 9th and Superior, occupying the ground where the remodeled Saint John Cathedral stands today. It was begun in 1848 and was completed amid great rejoicing by the Irish people of the East Side in 1852.

- Established Saint Patrick’s on Bridge Avenue in 1853 for the Irish on the West Side.

- Began a convent school for girls in 1850 under the direction of the Ursuline Sisters in an old mansion on the south side of Euclid Avenue near East 6th Street. He had persuaded these nuns to come from France to take this missionary charge.

- Established an orphanage in 1851 on the West Side at Fulton and Monroe Streets and staffed it with a community of sisters he founded as an offspring of the French Ursulines. It was to care for the Irish children who survived the immigration voyage but whose parents did not. Connected with the orphanage the bishop began a hospital under the care of these same sisters. The hospital failed for a time, but was opened for good with the aid of money Publicly subscribed by the whole Population of Cleveland in 1864. Bishop Rappe called it Saint Vincent Charity Hospital, and he staffed it with the Sisters of Charity of Saint Augustine who had begun the orphanage. This was the first public hospital in the city; it was opened originally to care for wounded Union Army soldiers who were generally discharged when wounded in the Civil War and sent home to find medical care as best they could. There was none in Cleveland until Charity Hospital was opened. The hospital marked a radical departure from the Catholic policy in the new Diocese of Cleveland which up to this time cared only for its own people. This was the first sign of a developing diocesan maturity, albeit thrust upon the diocese by the Civil War.

Bishop Rappe lived a block from his new cathedral on East 9th Street and was, in fact, pastor of this cathedral parish. This parish was in his time the largest parish in the diocese, and was a territorial, which is to say, an English speaking parish. This meant that all the Irish immigrants on the East Side belonged to the parish, and for them the bishop developed a specific policy. The Irish immigrants in the cathedral parish were to acculturate with their American neighbors as best they could. They were to seek as soon as possible such things as steady jobs, frugality, home ownership and what we might call upward mobility. Only in the matter of temperance did the bishop permit the cathedral Irish to form their own ethnic society.

That rather popular society took the name of Father Matthew, the Irish-born temperance crusader who had preached a mission at the Cathedral in 1851, at which thousands, including the bishop himself, took the temperance pledge. It would seem that these people kept this pledge; crime among the Irish suddenly decreased. They began to become home owners and to develop a sense of frugality urged to deposit or invest their money by the existence of the bishop’s bank (which lasted no more than a decade). It took no more than a generation for the Irish on the East Side to see themselves as upwardly mobile and capable of competing for jobs, not with one another, but with the native-born Yankee Clevelanders. They accepted the urging of Bishop Rappe that they should no longer see themselves as Irish or even Irish American, but simply as American.

Any priest stationed at the Cathedral during Bishop Rappe’s time who saw himself as an Irish leader in an Irish parish was quickly transferred to the most rural parish which could be found where he was told to practice his nationalism among farmers. A case in point was that of Father T.P. Thorpe who, while at the Cathedral in 1864-65, became active in the Fenian movement. His efforts got him transferred in 1866 to Norwalk, Ohio. The Cathedral and two new parishes which were founded in the decade between 1855 and 1865, Saint Bridget’s on East 22nd Street near Charity Hospital and the Immaculate Conception at East 41st and Superior, each comprised totally of Irish immigrants, were to be American at once.

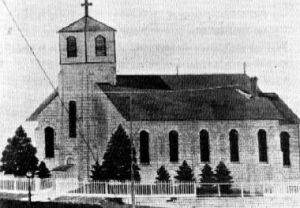

Saint Patrick Parish

This was not the case at all on the West Side. To be first pastor of Saint Patrick’s on Bridge Avenue in 1853 the bishop appointed Father James Conlon, an Irish-born, quiet, conciliatory man whom the bishop seems to have trusted implicitly. Conlon organized his parish as an Irish parish from the very beginning. He encouraged the preservation of Irish culture more by tacit approval than by any other means, but he made it quite clear during the twenty-two years of his pastorate at Saint Patrick’s that his people were Irish Catholics. They were not to go to worship at the German Church of Saint Mary’s on West 30th Street nearby, nor were they to mingle with their native American neighbors. Above all, Conlon felt, his people were not to marry nor even to, “keep company” (his words) with the Yankees. Catholics were to marry one another. In this he seems to have succeeded; in no year during his pastorate does one find more than two religiously “mixed marriages” in the parish records of St. Patrick.

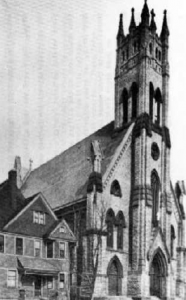

At Saint Patrick’s there were Irish literary, dramatic, cultural and musical societies as well as a temperance society. There were Irish benevolent societies in the parish as early as 1855, and most importantly perhaps, the people at Saint Patrick’s were urged by Conlon to build their church as an exact duplicate of one he had known as a boy in Ireland. It still stands, although Conlon did not live to see it completed, a gaunt high-ceilinged building in sharp architectural contrast with the warm French Gothic design of the original Saint John’s Cathedral. If all of this meant that the people of Saint Patrick’s were to sacrifice upward mobility to preserve the clannish neighborhood of the parish, Conlon seems to have said, “So be it.” Thus, not one, but three generations of Saint Patrick’s men continued to work as laborers on the docks unloading the ships coming to Cleveland laden with the newly discovered iron ore from Minnesota. Or they found employment in the new steel mills rising in the flais near the parish. Their neighborhood stayed tightly Irish nearly halfway into this century; it was proud, independent and aloof, long after James Conlon died in Charity Hospital in 1875.

Saint Malachi Parish

Perhaps none of this could have continued had an Americanist of the persuasion of Bishop Rappe succeeded Conlon or had pastors of an Americanist bent founded the parishes split off from Saint Patrick’s. This was, in fact, not the case. In 1865 Bishop Rappe appointed Father James Molony to begin a new parish east of Saint Patrick. He called it Saint Malachi, and it embraced the poorest of the poor in what came to be called by old Clevelanders, “The Angle.” This parish overlooked the docks as did Saint Patrick’s, but was closer to them, indeed within walking distance of the men to their work. Molony, himself a quiet man like Conlon, remained pastor of Saint Malachi from 1865 to 1903. Toward the end of his life he came to be regarded, perhaps because of his remoteness from his people, as something of a neighborhood saint. He permitted this Irish reverence for himself and held his parish together, not so much by force of positive leadership, though he gave that in a quiet way, but rather because of this reverence in which his parishioners held him.

In any case, Saint Malachi became an even more intensely Irish parish ghetto than did Saint Patrick, so much so that the territory of the parish was more or less closed by force to all outsiders and remained so until after the death of Father Molony in 1903. Second and even third generations of its sons and daughters married one another and remained members of the parish by building additions to the rear of their parents’ homes, or by buying houses made vacant by the deaths of older parishioners.

Summary of Differences Between West Side and East Side Parishes

Here then is a summary of the early differences between the West and East Side Irish communities: first, the East Side Irish immigrants of the 1850’s and 1860’s, had really only one parish to which they could belong. The pastor of that parish, Saint John’s Cathedral, was the French-born bishop who desired that the Irish people of the parish should become American as soon as possible. He continued this policy in the two Irish territorial parishes which he founded as offshoots of the Cathedral and appointed as pastors of these parishes men who he felt would extend and reinforce this policy. But on the West Side he permitted Father Conlon and Father Molony to go their own way in union with their people; thus both their parishes became centers of Irish nationalism in the absence of any acculturating leadership.

Second, when Father Conlon died with his parish church uncompleted, Bishop Rappe’s successor, Bishop Richard Gilmour, sent to Saint Patrick’s a priest who had developed a modest reputation as a builder in Youngstown a decade earlier, Father Eugene O’Callaghan. While he completed the building of the church Father Conlon had begun at Saint Patrick’s by heroic effort Father O’Callaghan drew the parishioners together during his three year pastorate (1877-1880) by appealing to their Irish nationalism and sense of community which had been rooted in the parish since Father Conlon’s time. O’Callaghan never was an Irish nationalist himself in his previous assignments; indeed he was even more of an Americanist than Rappe, but at Saint Patrick’s he adapted himself to the character of his people and to their aspirations, and encouraged their Irish nationalism, albeit without much heart. When the church at Saint Patrick was completed in 1880, O’Callaghan promptly resigned the parish, which was by that time second in size only to the Cathedral (Saint Patrick had thirteen hundred families, the Cathedral two thousand families), and founded at his own request Saint Colman’s parish at West 65th Street near Lorain Avenue. Here he spent the last twenty-one years of his life serving the most neglected of Cleveland’s Irish poor who had immigrated to the city after the second major famine in Ireland in 1878. At Saint Colman he had no choice but to continue his policy begun at Saint Patrick. He encouraged his people to preserve their Irish heritage in every way they could, and indeed Saint Colman remained an Irish parish and community right up to World War II, forty years after O’Callaghan’s death in 1901.

One might speculate that this occurred for two reasons: O’Callaghan’s people were so poor that a nostalgia for the land of their birth was often all that sustained them, and Bishop Gilmour was not at all the Americanist Bishop Rappe was. Although he wished the Cathedral parish to be American, he never imposed this view on pastors of any ethnic parishes. Indeed, the Bishop founded many of these ethnic parishes, and unlike his predecessor he encouraged the non-English speaking parish. Hence he hardly could stifle the same aspirations of the English-speaking ethnics at Saint Patrick’s and Saint Malachi’s.

A third difference between East and West Side parishes is that, quite unlike the newly formed parishes of the native born Irish on the East Side which continued Bishop Rappe’s policy, the major West Side Irish parishes of Saint Patrick and its offshoots, Saint Malachi and Saint Colman, all continued, each for reasons which were somewhat similar, the Irish character which was present at their founding, right up to our own time. One need note only that the annual Saint Patrick’s Day Parade, begun in 1875 as a purely West Side Irish event (it did not become a downtown demonstration until 1878) continues to have its origin in the West Side Irish American Club and in the Gaelic Civic Society. Both organizations are led today by Irish who live on the West Side and who seek, at least in this somewhat flamboyant way, to recall their heritage in Cleveland, a heritage they have kept alive, if only one day a year.

The fourth and final difference is that during the crucial years of the maturing of the Famine Irish on the East Side, that is to say in the period between 1875 and 1895 when the children of the original Irish of the 1840’s and 1850’s were beginning to marry and to move out of the parishes of St. John’s Cathedral, St. Bridget and Immaculate Conception, they formed new parishes which were to continue the logical consequences of Bishop Rappe’s Americanist policies. These new parishes were St. Aqnes at East 79th and Euclid in 1893; St. Thomas Aquinas at Superior and Ansel Road in 1898; St. Edward on Woodland Avenue at East 69th Street in 1885; and St. Philomena on Euclid at Wellesley in East Cleveland in 1902.

In spite of the fact that all these parishes were mostly Irish in makeup, they were American in style. Perhaps a major contributing cause for this was the fact that these new parishes also embraced the American born children from the German parishes of the East Side, St. Peter’s at Superior and East 17th Street and St. Joseph on Woodland Avenue at East 24th Street. These people, relegated by Bishop Rappe to a secondary role in the Cleveland Church until they could learn the language and culture of their new land, seem to have desired to become as much American as did their Irish neighbors on the East Side. A pastor in one of the new East Side parishes could hardly feel free to imitate the style of the Irish parishes on the West Side.

Father Gilbert Jennings, who founded St. Agnes parish in 1893, is a case in point. Jennings was born in Ravenna, Ohio, in 1856 of Irish-born parents. He was ordained in 1884 and immediately assigned at pastor in Jefferson, Ohio, the home of Josh Giddings and Senator Ben Wade, who were instrumental in founding the Republican Party in 1856. When he was assigned to form the new parish of St. Agnes, Jennings brought with him some unique ideas on parish administration and organization. Influenced by his experience with the Yankees in Jefferson and by the radical Americanism of Archbishop John Ireland of Saint Paul, and Bishop John Lancaster Spalding of Peroria, both of whom lectured at St. Agnes frequently, Jennings adopted the town meeting theory of village government to parish administration. All the people were invited to meet and decide on parish policy. They formed a covenant with their pastor and with one another before God, mirroring the style of the Congregational Churches of the Yankee a half century earlier. They agreed to tithe in order to construct their new church buildings, thus eliminating the frequently obnoxious system of collection by envelope and family pew rent in vogue elsewhere in the diocese.

Jennings favored a parochial school and built one, but only after he reminded the people that the school had to be excellent and not a mere Catholic alternative to the public school. He opened the first kindergarten of the diocese in his school and laid special emphasis on adult education in the parish to continue the upward mobility of his people. In his public addresses, specifically in one given at the graduation exercises at the University of Notre Dame in 1907, he asked for the first time the question echoed by John Tracy Ellis forty-nine years later, “Where are America’s Catholic intellectual leaders?”

Jennings saw his parish as a community of resources to be used by all his people to enable them to move beyond the middle class laboring-man model of the West Side Irish. He urged his parishioners to become involved in the professions, in government, in social leadership and to bring to these enterprises a Christian presence. Many of them did this and in doing so doomed Father Jennings parish: as soon as they began to achieve wealth comparable with that of the Yankees, St. Agnes’ original parishioners moved out into the new and exclusive suburbs of Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights. By 1941, when he died, Jennings had seen his parish go from a tight community of upward bound young Irish and German families to an incipient slum of boarding houses and tenements which would one day become the Hugh area. If this disturbed him, he never showed it. On the contrary, he seems to have been proud and happy that his people were doing so well in the city; he enjoyed conversation with them when they came back to visit him to give him donations to pay for the great stone and marble church he built unwisely in 1916, the precise year that his people of wealth were beginning their exodus to the suburbs. This church, beautiful as it once was, was demolished in 1975 for want of financial support.

East and West Side Differences in the Twentieth Century

The twentieth century saw some startling changes in the attitude of ethnic consciousness among Cleveland’s Irish population. For some, newly found wealth and upward mobility had finally brought many third generation Irish to a position where they completely forgot or denied their Irish heritage. For them, the immigrant church was ended. They moved to the suburbs and gave great loyalty to their churches. However, they no longer saw themselves as Irish Americans, but simply as Americans. There are great numbers of descendants of the original East Side Irish who now live in the eastern suburbs. They often can trace their names back to the founding families of the first East Side parishes, the Cathedral, St. Bridget, Immaculate Conception, St. Edward and Holy Name. But for them, St. Patrick’s Day passes unnoticed or is observed at the Cleveland Athletic Club as they vaguely recall some heritage long since forgotten. They resemble more often than not the Wasps with whom they try to compete, usually without success. A visit to the West Side Irish American Club would be for most of them unthinkable. Perhaps this is a pity.

But for a second group, generally rooted in the near West Side parishes, acculturation and assimilation have not come so completely. St. Patrick’s Day and its parade belong to them; they continue to support the West Side Irish American Club. They keep alive at least some semblance of their heritage in their dances, their radio programs, their contact with relatives in Ireland and a sense of the community their ancestors had experienced in their old parishes. Sixty years ago their ancestors actually aided the Irish Rebellion in Ireland and they poured considerable money into the process of the formation of the Irish Free State. Significantly, many of these West Side Irish who now live in Cleveland’s western suburbs are related to one another and are aware of these relationships. Weddings of their children, more often than not, have a tendency to show a familial focus on the transmission of a heritage. Funerals, and the wakes that go with them, continue to be the occasion of a gathering of the clans and the remembering of past days. It still is difficult for a young person to break out of the clan, and if he should do so, he usually feels alone and suddenly rootless.

Now what is one to make of all this? To a considerable degree, a basic and radical difference in mentality between East and West Side Irish exists to this day. Surprisingly enough, the truth of this difference has been tested by the black man. It was he who on the East Side replaced the second and third generation Irish in their strongest parishes — at St. Agnes St. Thomas, St. Aloysius and St. Philomena. Many factors are involved in this phenomenon but perhaps a major part of it is that the East Side Irish were willing to sell their houses to the black man when they moved out. On the West Side it was clear that to sell one’s home to the black man was, and still is, regarded as a betrayal of one’s neighbors and of the community.

This seems to be precisely the point of difference between East and West Side Irish today. Neighborhoods change slowly on the West Side, because they are to a far greater degree “communities” than those on the East Side. These West Side communities are rooted in church affiliation which one must see as church or parish centered.

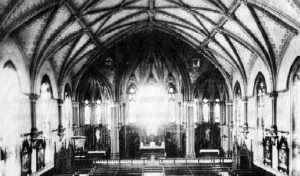

For example, rarely does one find the equal of the sense of community generated by the building of Saint Patrick’s church on Bridge Avenue between 1877 and 1880.[1] When the people of Saint Patrick’s found they could not afford to build the church Father Conlon envisioned for them before his death in 1875, they sought, under the leadership of Father O’Callaghan, to do the work themselves. The church, which is of momumental proportions, is built of Sandusky limestone because O’Callaghan could obtain that stone free from a quarry in Sandusky. The people organized themselves into teams in which every man who was able participated. They cut the stone themselves, and even used the wagon of the local undertaker to transport the stone from Sandusky. The whole project took two years; each trip took one week — over 100 trips were made. The church was under roof by late 1878; then those who had been stone cutters earlier became the carpenters, glass workers, altar builders and plasterers.

The whole project was pretty well completed by 1880, and much of the work of the builders remains visible to this day. One notices that the stones are poorly cut and that the roof, which is really a giant A frame, covers over a set of fine clerestory windows which the builders installed but could not devise a way to roof properly — they had no architect. Even the pillars in the church tell a story. To get wooden beams to support the roof, Father O’Callaghan sent buyers to New York to purchase the main masts of the Cunard sailing ships which were being dismantled in favor of the new transatlantic steam ships. These were the very sailing ships which had brought the original Famine Irish to this country. Once they were in place holding up Saint Patrick’s roof, the people of the famine time could look at the pillars and recall their own immigrant experience, an event which they had seldom if ever allowed themselves to think about until it was made so graphic to them.

Thus their church, which they had built by hand, and their past were all symbolically visible as they worshiped. Both had generated a remarkable sense of community and of recall. The building itself held the people to the neighborhood for years: no East Side church built by contract could achieve this sense of neighborhood and community of service, no matter how expensive or ornate its style. In spite of its classic beauty and design, and its cost, the great stone church at St. Agnes held very few of its original people to the neighborhood. In fact, it was demolished in 1975 by the Diocese of Cleveland because it, as with St. Thomas church, had become a useless financial burden to the Diocese.

On the East Side upward mobility was predominant in the minds of both priests and people; churches, no matter what their wealth, were in the long run irrelevant. This was not true on the West Side where selling one’s home to move to the suburbs seemed to have been an abandonment of one’s heritage as well as one’s peers. It may well be that all of this is changing today. Yet still the West Side Irish who have moved out from their immigrant parishes seek the same sense of community in their new parishes in Lakewood, Rocky River and West Park, Fairview, North Olmsted, and Bay Village much more so than do the Irish of the East Side.

By contrast, the East Side Irish are today generally invisible as ethnics as they blend with their equally invisible fellow ethnics in Cleveland’s East and Southeast suburbs. These Irish people, who more often than not can trace their roots back to the parishes of the Cathedral, St. Bridget and Immaculate Conception, have little or no sense of their ethnic background. They continue to seek an ongoing upward mobility. Their parishes are large and usually impersonal and they often fit perfectly the description given by sociologists to the modern suburban Wasps who also have forgotten their roots — the “rootless Americans.”

Somehow the pattern on the East Side for the Irish in the long run seems to resemble that of the native Americans on the East Side, probably by imitation. If so, then one must conclude that the Wasps have unconsciously achieved the thing their ancestors could never achieve in three centuries in England with regard to the Irish, the total eradication of Irish nationalism and ethnic consciousness. If this is so, one also must conclude that the Wasps achieved this incredible result at the price of the loss of their own ethnic consciousness. The Wasps have been forced into the role of the paradigmatic group by countless social, political and religious pressures as they live in the presence of the vast diversity of ethnic groups, all of whom have come to Cleveland since the time of the Connecticut Land Company. For this reason, the Wasps of today fail to lead the city politically in spite of their long-standing wealth in the community. Occasionally one of them will venture into Cleveland politics as did Seth Taft in a mayoralty election, only to be badly defeated by a black man like Carl Stokes, or a man whose origin lies in the non-English speaking community like Ralph Perk.

Because the Irish and the Wasps on the East Side are so similar and so locked in competition with each other, they seem unable to form any kind of political coalition. The West Side Irish, who to this day are more united in their ethnicity and their Politics, are still not numerous enough to win with a candidate of their own the office of Mayor of Cleveland. They can produce Congressmen like Jim Stanton and Michael Feighan to represent them in Washington, but they have produced no mayor of Cleveland.

Thus we see that the contrast in vision regarding acculturation begun by Bishop Rappo on the East Side and Father James Conlon on the West Side over a century ago have contributed profoundly to the fundamental difference which remains to this day between the East and the West Side of Cleveland.

However, the East Side Irish today cannot claim any real success in their competition with the Wasps. Many East Side Irish have achieved considerable personal wealth. That wealth does not really match proportionally the wealth of the descendants of the original Western Reserve families. For the most part the East Side Irish have always disdained politics; the Wasps have not. But they are seldom elected. If social acceptability is what the wealthy East Side Irish seek, they have failed in this also. One searches in vain for any significant number of Irish names in the membership lists of the clubs of prestige on the East Side. Very few families of Irish origin belong to the Union Club or to the Country Club, both of which require new members to pass a board of review.

The issue is more than one hundred and twenty years old. The Wasps will not socialize with the people whom they never accepted, the Irish. The East Side Irish have no club to receive them as peers among peers, and for them to join the West Side Irish American Club would be an unthinkable step backward. Indeed, they have lost their heritage and they cannot relocate it at the precise time when, at least socially, every other ethnic group in Cleveland is rediscovering its heritage and exploiting it.

None of this is presented to extoll either the West Side Irish or the East Side Irish. It is simply a set of observations about both groups and an effort to raise the question as to whether either was right. This writer suspects that each was right in the course they pursued insofar as each had at least achieved the goals they (or their clergy) set for themselves a century ago. It is the sense of identity for the future, about which we shall speak later, that causes one to wonder.

- This writer has noted this phenomenon in his book (Alba House, 1971). ↵