Part I: The Irish in Cleveland: One Perspective by William F. Hickey

Chapter 3: Settling in Cleveland

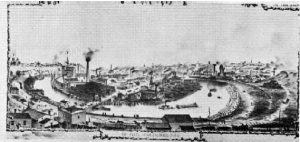

Whatever the toll it took in lives, the Ohio Canal, among other things, made Cleveland a very important city. It transformed it into a strategic location, an exchange point for goods from the South, as well as the East, not to mention foreign shores. In no time long lines of wagons jammed its streets and vessels of every description crowded its twisting river, the Cuyahoga. By 1830, with the canal only a bit more than half completed, Cleveland was on its way to becoming a boom town.

What is Meant by “Irish”

The debate still goes on as to who were the first Irishmen to settle in Cleveland. As the Jesuits are wont to say, argument without a definition of terms is absurd. Thus it 611 comes down to what constitutes an Irishman, the genuine article, as opposed to hybrids such as the Anglo-Irish or Scotch-Irish, which were created by implantation and immigrated to this land from the English fiefdom of Ulster.

In this background piece I purposefully omitted mention of the Province of Ulster for two reasons: first, in the period of Irish emigration it was peopled primarily by non-Irish, and second, so much has been written about it of late that everyone should be familiar with its role as England’s last vestige of an empire. Whether its people had been there for centuries during the migration or merely decades, they were not Irish by the normal ways of measuring a race — language, blood relationships, culture and religion.

However, as to the Irish in Cleveland, we could note that there were men with Irish surnames in the Connecticut Land Company, the organization responsible for the city’s existence. Then, too, is the fact that Cleveland’s first mayor was a man named Alfred Kelley. Another man named McIntyre stoutly defended the city durina the War of 1812, even though the British attack failed to materialize. But these men were not Irish in the true sense of the definition. Irish surnamed, yes, but not Irish in thought, word or action, and especially not in the intangible called culture.

So for the purposes of this work, the Irish will be those who emigrated from the 26 counties that lay outside Ulster and those very few from within who were not of the Orange Order. The Irish are those who followed the way St. Patrick laid out for them and not Good King Billy. While those requirements may seem stringent, they are eminently fair when one considers that 95% of all the peoples who lived on that island fit those standards.

The First Irish in Cleveland

In light of that, it is safe to say that the first Irish to settle in Cleveland were those who came in the early and middle 1820’s. There were only a handful of them and all had come from their labors on the Erie Canal, seeking a better way of life. They had been told that the life of a seaman was to be preferred to that of a canal digger. Only the most adventurous of them were willing to give up their steady work to go chasing such a rainbow, but some did, spurred on by thoughts of material gain, the quicker to get money to send home so relatives could join them here.

Some did manage to land berths on Great Lakes sailing vessels, but most had to settle for jobs on the docks. They didn’t complain; they were lucky to get them. This handful of men was given a little nod by the city’s established citizens, for they were so few in number as to be of no consequence. They stayed in their place by the river’s mouth and few Clevelanders were even aware of their existence.

It was a different matter in the next few years, especially when the summer of 1825 rolled around. The Erie Canal had been completed and the Ohio about to get under way. The Irish began piling into the town in measurable numbers and the reaction among the local Yankees was quite different — they didn’t like the rag-tag men who spoke English with a brogue and were obnoxious in other ways as well. Work on the canal lured most of them away, but by the best estimates of historians of the day and newspaper accounts, close to 200 Irishmen remained as squatters.

Like their pioneering brothers before them, they headed for the docks seeking work. But there was another reason for doing so: the Yankee establishment let them know in no uncertain terms they were not welcome in other sections of the still small, but bustling, community. The attitude of the local residents was understandable, for the Irish were a different breed — foreign, footloose and free-spirited, wild men all.

One can imagine the impact the 200 Irishmen made on the more orderly Yankees, who numbered only about 1,000 themselves. They strongly resented this invasion by rough and tumble, mannerless men, who seemed interested only in obtaining the bare necessities of life and drinking the saloons along the riverfront dry. The Yankees had a decision to make and they made it quickly — they ceded the marshlands at the river’s mouth to the Irish.

Whiskey Island

One must picture that land as it was when the Irish first huddled together on it. When Moses Cleaveland first came upon it, it was a delta and he had some difficulty finding the main channel to the river itself. The fact that he had to come upriver three-quarters of a mile before reaching ground solid enough to stand on gives one a clue as to its composition. One of the men in his company, in writing later about the founding father’s trip upriver, revealed a nice touch of humor. “I could not help but re flect that history was repeating itself,” he wrote, “Moses, like his namesake, was caught in the bullrushes.”

The land around the river’s mouth and for a half-mile south of it was pure swamp, with the exception of a ridge that had been formed by the Cuyahoga’s current as it curved westward on its way to emptying in Lake Erie at a point just east of present day Edgewater Park. It would not be until 1827 that federal funding and engineering expertise allowed local citizens to dig a channel, creating the river’s mouth as we now know it. The Irish, naturally, did the digging.

Since that knoll was the only habitable land anywhere about, the Irish took possession of it and began erecting tarpaper shanties on it. Amusingly enough, that stretch of slightly elevated land was once the “farm” of Lorenzo Carter, the city’s first resident, who had built a still on its easternmost end. The land the Irish settled on had been called Whiskey Island for years before they arrived, but if it hadn’t been, it would have had to have been renamed.

The Irish who squatted there gave a new meaning to the island’s name — they made it a real island of whiskey. In its heyday it boasted of having 13 saloons, a considerable achievement since it was only a mile lona and a third of a mile across at its vtidest point. It was from the first and for many years remained the wildest, bawdiest section of Cleveland.

Whiskey Island was not actually an island, but rather a peninsula. Furthermore, it never was an island, not even when its first inhabitants, the “Irrinons” or Erie Indians, made a permanent camp there in the middle of the 17th Century. It is amusing to note that the French called the Eries “The Cat People,” while two centuries later, Irish dock workers would come to be known as “Iron Ore Terriers” or “The Dog People.” Those two tribes, the Eries and the Irish, would have had a rollicking good time had they the chance to meet, for both were of mercurial temperament, intemperate and amazingly stubborn, especially when it came to admitting the odds were against them.

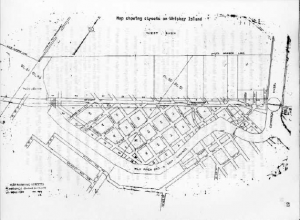

Be that as it may, when Moses made his way through the Cuyahoga’s bullrushes, Whiskey Island was a peninsula jutting westward from where the river’s present day mouth is to about West 54th Street. When the river was straightened to allow nature to assist in the clearing of the sandbars which clogged its mouth, the original entrance to the lake was filled in and the peninsula then became anchored on its western end.

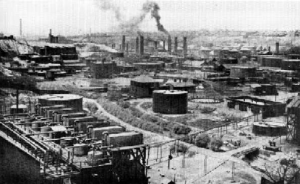

It is now difficult to imagine what a beehive of humanity Whiskey Island was from the 1830’s to the turn of the century. All there is on it now are a number of grasshopper-like machines called Hulett Unloaders, oil storage tanks, a few warehouses, the International Salt Company’s large works, railroad yards and, of course, docks. The only traces of humanity left on the island are remnants of Riverbed Road and footers from a number of houses and business establishments. Oh, what it was in the days of the early Irish settlers!

Whiskey Island was triangular in shape, almost an isosceles but not quite, with its northern boundary as its base. The island’s northern limits were where the Penn-Central mainline tracks now run. The land now north of there resulted both from the action of the lake and the action of men, who carted fill there faster than the lake could reclaim it.

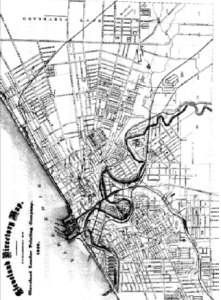

It is even more difficult for one looking over Whiskey Island today to imagine that all told, it had 22 streets crisscrossing it. Any doubts of this can be dispelled by a consultation of early Cleveland area maps. The streets were laid out by a group of ill-fated investors who purchased the land from the estate of Lorenzo Carter. The longest thoroughfare was Bennet Street, which ran the length of the island along its northernmost boundary. It now serves as the roadbed of the Penn-Central mainline tracks.

With the exceptions of Bennet, Albert and Toledo Streets, all others ran northwest-southeast or southwest-northeast, creating the crisscross pattern. Bennet, of course, ran in a West-east direction, while Albert and Toledo Streets ran in a north-south direction. The latter two were at the eastern edge of the island and only one block long. There was also an unnamed alley parallel to and a block west of Toledo Street, which some of the early inhabitants dubbed “Sin Alley.”

As one can imagine, such a pattern determined that streets near the base angles would be shorter than those originating from the apex. Thus, Carter Street on the western end and Elm Street on the eastern were both only 600 feet, or two blocks long. The longest street other than Bennet was Macy, which ran in a southwesterly-northeasterly direction for almost a half-mile. A man walking in a northwesterly direction from the point Macy Street originated would cross, in order, Thompson, Tyler, Baldwin, Pratt and the forementioned Carter Street.

If he were to walk in a northeasterly direction from the same spot, he would cross, again in order, Andrew, Gidings, Union, West, Hickory, Mulberry, Center, Elm, Sycamore and Riverbed Streets. The latter two streets were longer than Elm because the eastern base angle contained an irregularity, which also served as the terminus for two other streets, Willow and River, which actually ran parallel to Macy, but for most of their length were on the south side of the old river bed.

The blocks created by this crisscross pattern were 300 feet square in the center part of the island and, of course, varied in size as the streets drew nearer to the base angles. To be sure, there were some fascinating geometrical shapes in the remaining blocks, including rectangles, trapezoids, parallelograms and a rhomboid or two, all of which were hardly conducive to helping an Irishman find his way home after a night of tippling.

Life on Whiskey Island

It was often said, and with some justification, “that most nights on Whiskey Island were lively ones and when the police answered a riot call, the horses would automatically head in that direction.” The Irish who inhabited Whiskey Island were, indeed, hard-drinking, brawling and often lawless men, but then, they had plenty of reasons to be all three. They were rootless outcasts of society, a shunned and largely despised group of men, who despite their crude ways, Were not insensitive to the injustices that had been heaped upon them from the moment they first set foot on American soil. They had to take out their frustrations on someone and since no one else was available, they took them out on one another.

Many of them had aspirations that went beyond three squares, a place to flop and a bottle of whiskey, and they were to prove that in relatively short order, despite being caught up in a mentality common to oppressed people. The Irish of early-day Cleveland fluctuated between rage and despair and needed their bottles and brawls to stave off madness on an epidemic scale. If it weren’t for the fact that they were able to retain a collective sense of humor, none of them would have made it, for then they didn’t even have the consoling words of a priest to get them through their worst moments.

Whiskey Island was well within what the Yankees called “the fever and ague line.” It was, in fact, the very heart of the swamplands in which resided the dread malaria-carrying mosquito which left its mark upon the Irish who dwelled there. It was the canal story all over again — the only question that remained was which would get to the Irishman’s body first, malaria or diarrhea. Living on that patch of land in the 1820’s took a heap of surviving.

Those early Cleveland Irish and their brothers working on the Ohio Canal in various parts of the state were also plagued by the two-legged variety of creature, the one called man. They were often swindled by hucksters and even more often were victims of a more direct form of thievery. An editorial in the Cleveland Leader, dated June 6, 1826, railed against the unfair treatment afforded the Irish canal diggers, noting that many subcontractors were systematically cheating them out of their pay, meager as it was.

It was the old “company store game,” in which the worker, no matter how long or hard he might labor, finds himself in the position of owing the company money at the end of each month. The canal Irish had little choice but to make their mark on the contractor’s ledger and try to square things the following month, since jail terms for debtors were still the law of the land. It was a feat rarely accomplished, even when abstinence was tried. Nevertheless, things were bound to get better and they did, if one can overlook an epidemic of typhoid fever which originated in the canal area.

New Work on the Canal Boats

On July 4, 1827, the first canal boat navigated the 37 miles between Akron and Cleveland, passing through 41 locks. Although the two northernmost locks, the final links to Lake Erie, were not yet completed, it was cause for great celebration among local citizens, for it meant the city would soon take its place as a trading center of importance. It was also celebrated by the more perceptive Irishmen, as they saw in those flat-bottomed bateaux that plied their way up and down the canal, an escape from digging the canal itself.

They hired on as deck hands and cooks, some even landed jobs as helmsmen. This was the Irishman’s first step in upward mobility, this exchange of a shovel for a hawser, frying pan or ship’s wheel. It was difficult work, but compared to what he had been used to, it was like stealing money.

However, there was one little catch to their new life, but one considered inconsequential by the Irish. One of the principal reasons the Irish were hired on the canal boats had to do with their reputation as excellent brawlers. As the canal became congested with traffic, disputes would arise as to which barge would pass through a lock first when two arrived simultaneously. Since time was money, it became a somewhat important matter. The barge captains solved the problem by the age-old method of limited combat. One man, presumably the toughest, was selected from each barge to do battle for the honor of the boat and, of course, the economics involved.

| 1. St. John’s Episcopal Church | 6. Cleveland Elevator |

| 2. Union Elevator | 7. Glaser Brothers Tannery |

| 3. St. Malachi Catholic Church | 8. Bosfield & People Pail Factory |

| 4. Cleveland-Columbus-Cincinnati Ry Round House | 9. Cleveland Furnace Rolling Mills |

| 5. St. Mary’s of the Flats Catholic Church |

The two appointed gladiators would leap from their barges and engage one another on the adjoining towpath. There were no Marquis of Queensbury rules hampering these brawls, anything and everything was considered acceptable, including biting, gouging and kicking a man’s procreative organs. Ouite naturally, the winner’s barge got to go through the lock first. No more back spasms for the Irish, just a few broken skulls.

The canal workers who opted for the life of a bargeman saw their former ranks filled with yet more Irishmen, who continued to stream out of the ghettos of eastern seaboard cities by the thousands. In 1829 it was estimated that 1,200 immigrants were arriving in northeastern Ohio each month, and a goodly number of them were Irishmen looking for work on the Ohio Canal. Most of these newcomers, however, were shuttled downstate and across the state to the Miami-Erie Canal. They apparently were every bit as boisterous as their brothers who had worked on the Erie and who were presently working on the Ohio. They spent their leisure hours in a village called Providence, and as one citizen of that western Ohio hamlet remarked: “It seemed to make no difference to them (The Irish) that our town was named for the Almighty. Every Saturday night they turned it into hell.”

Moving Out from Whiskey Island: the 1830’s

As far as the Cleveland Irish were concerned, things were looking up a bit. The boom hit in 1830, initiating a full decade of prosperity that was blemished only by the Panic of 1837. The port, hence the docks, bustled, providing more jobs for the men with the brogues. Other laboring jobs opened up also, as the business district, which still fronted on the river, became a thriving center of forwarding and commission warehouses, in addition to the ship chandler’s storehouses that seemed to be everywhere. It was menial work, but it also meant that more Irishmen had a chance at stability.

As the 1830’s progressed, some Irishmen even made it up the hill to the city proper, where they found jobs in the building trades, usually excavating foundations or carrying materials. The newly-arrived Germans, far more skilled in the crafts, latched onto the more artistically demanding and financially rewarding jobs. Digging foundation holes had its hazards. There were cave-ins and sometimes a partially constructed wall would come tumbling down most unexpectedly. One unfortunate Irishman’s death was recorded in the Cleveland Leader on July 7, 1835. It read: “Patrick Shields, an Irish laborer, was killed yesterday by the falling of a building wall on Superior Street. He was single and 34 years of age.”

The 1830’s saw the Irish firmly entrench themselves in Cleveland. They began to occupy both sides of the Cuyahoga, from the mouth of the river up to and a little beyond what is now Detroit Avenue. They also began careers as businessmen. Patrick Malone opened a butcher shop and John Murphy petitioned for a license to operate a public house. Not to be outdone, Thomas Maher opened a greengrocers shop. No tycoons in the lot, but upwardly mobile men, to be sure.

The 1830’s also saw the completion of the Ohio Canal, for in the summer of 1832, a locally owned boat became the first to travel the 309-mile route between Cleveland and Portsmouth on the big river. The day of the Irish canal digger was all but over. Some stayed to dig auxiliary canals that formed a large web of waterways downstate but the main digging was a fait accompli. Many, as noted before, stayed on the canal as deckhands on the barges and began settling down in various towns along the waterway. Descendants of those early boatmen can be found in almost every town of size along the canal, but most notably in the northern section of the state. Any number of Akron, Canton and Massillon residents named Sheridan, O’Brien, Boyle, O’Malley and Sweeney, to mention but a few, can easily trace their family patriarchs to their days as canal boatmen.

The Irish in Cleveland at this time were not numerous, but their numbers doubled in the 1830’s to around 400. Included in that community were increasing numbers of women, sisters of canal diggers who had been sent passage money and urged to make the trip. The footloose were being supplied with hobbling pins and the chance to beget progeny. There would be more than a few friendly Celtic faces to greet the Famine Irish upon their arrival in the late 1840’s. The canal diggers not only carved out waterways hundreds of miles long, they also paved the way for the Irish who came after them.

Not enough can be said for the brawny diggers who survived the poverty, pestilence and ostracism they encountered at every turn. Whatever their crude and boisterous ways, they were the ones who, through sheer grit and a laugh here and there, established the Irish beachhead on the shores of Cleveland and held on against overwhelming odds. They did more than that — they secured the docks and inland waterways for their own kind. May all their shovels rest easily, especially those of the forgotten souls who were unable to leave traces of themselves.

While the action of securing the docks might strike one as an achievement lacking in distinction or hardly being noteworthy, it was, in fact, an exceedingly important accomplishment. It meant the Irish who came after them would have a chance at life. The docks became the be-all and end-all of existence among West Side Irishmen. The fact that the work was grueling, low paying and often dangerous was neither here nor there, for it provided a lifeline and a hope for the future. Besides, when was an Irishman offerred any other kind of work?

Expansion Continued: Irishtown

Within two years after the Famine struck Ireland, the Irish population of Cleveland had soared to 1,024, and more were on their way. The influx of newcomers from the Emerald Isle truly shattered the serenity of the native born. The banks of the Cuyahoga could no longer contain them and the Yankees were forced to code more territory. The Irish moved both eastward and westward along the lakefront. They established a ghetto extending from the shoreline to Superior Avenue in the vicinity of what is now East 9th Street. They also slid westward and filled the area between the Lake and Detroit Avenue to about West 28th Street. No matter, it was all just one form of swamp or another.

From that initial expansion they would go on to establish other pockets of Irish power, east and west, sometimes leapfrogging established Yankee comunities. The Newburgh section is the prime example of this, but in that case, as in all others, they were simply following work opportunities. It should be noted that the Famine Irish had at least one predecessor in the Newburgh area, if we are to believe a letter dated August 16, 1833, written by one Arthur Quinn, who carefully datelined his missive back home, “Newburgh, County of Cuyahoga.” Quinn advised his relatives that “this is a poor man’s country, but unless he has land or can labor hard, he stands a poor chance at success.”

Working on the Docks: The Iron Ore Terriers

When stating before that the docks were “all,” as far as the Cleveland Irish were concerned, ot was my intent to use the word as a collective that included every activity that could possibly be connected tot he docks. The Flats, the heart of Irishtown, was also the industrail center of Cleveland, as well as the commodity exchange center. By 1840 there were four iron foundries located there and a “manufactory” for machine tools and, of course, several shipbuilding companies. The city’s true wealth lay in shipping, and that encompassed a plethora of businesses, all of which held possibilities for employment among the Irish.

Although iron, in one form or another, had been transported to the city for a number of years, the discovery of vast amounts of iron ore in Minnesota in 1852 was to guarantee the Irish of Cleveland solid work well beyond the turn of the 20th Century. Although the precious red mineral wasn’t much at first because of limited need — the first shipments in the 1830’s were of such small quantity that they could be handled in a few barrels on the deck of a passenger vessel — as the city developed into an industrial giant, it was delivered daily, thousands of tons at a time.

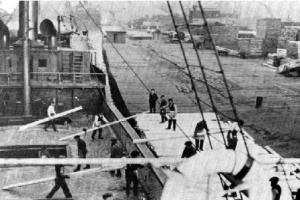

As the foundries and mills expanded, due to advances in metallurgy and the demands of a surging economy, the necessity to build cargo ships specially designed to carry ore became imperative. Hulking wooden vessels were built that were practically all holds, some capable of transporting 300 tons of ore.

It took 100 men four days to put that much ore into one of these vessels and took an equal number of unloaders seven days to clear the holds. By rights it should have taken eight days, for it is at least twice as hard to bring ore up out of a ship as it is to drop it down into one.

The job of unloading those ore-ladden monsters was the sole province of the Irish. It was unbelievingly back-breaking work, every bit the equal of canal digging and probably worse. The first tools the Irish were given to accomplish their task were rather primitive ones — a shovel and a basket. Through the benevolence of the shippers, they soon graduated to the shovel and the wheelbarrow. What made the work unbearable is that it got more difficult as it went along.

The reason for that was simple. The ore was unloaded, quite naturally, from top to bottom. Filling a barrow and running down a gangplank wasn’t too difficult, as long as the ore was near the surface of the hatch. However, as one removed more and more ore, he found himself standing deeper and deeper in the hold of a ship. Now he had to push the loaded barrow up a board plank as well. When he neared the bottom of the hold, he could barely see daylight — he had a long way to go.

Yankee ingenuity came into play within a short time, prodded as it was by economic reasons. The shippers had alseries of platforms erected in each hold, thereby enabling the shovelers to raise ore to the deck more expeditiously. More ingenuity on the part of the shippers resulted in a pulley system being devised, which allowed oversized buckets to be hooked up to a team of mules on the docks. When a bucket was filled, the mules would be spurred into action and their resultant straining would hoist the bucket of ore out of the hold and deposit it on the dock. It was not uncommon for 40 teams of mules to be employed in various combinations on a given day.

Upward Mobility: the 1850’s

During the 1850’s the Irish in Cleveland, those who had come from canal digging chores and those sent here by the Famine, made their first en masse move upward to better jobs. They began employing their native know-how in various ways. One such man was Anthony Aaron Gallagher, a Mayo native who spent his first few years here unloading iron ore. A gregarious man who seemingly got along with men from all walks of life, Gallagher hit upon an idea that was to make him a very successful and powerful man in Irishtown.

He first approached the ship owners and offered to take off their hands the troublesome and time-consuming chore of securing men to unload cargoes. For a commission, he would take full responsibility for the hiring and firing of the Irish stevedores. He must have been a persuasive talker, as the Yankee shipping magnates agreed to give him a chance to prove himself.

Gallagher then made the rounds of the docks, explaining his idea to the workers, pointing out to them that their hit-and-miss chances of obtaining a day’s work would be a thing of the past. He would guarantee the willing and able the security of regular work, providing, of course, that they would keep their end of the bargain by giving him “26 dry days of work each month.” He was careful to explain that they needn’t join Father Matthew’s Temperance League, but merely that they must be sober and in good condition at the morning roll call.

A good many workers thought Gallagher’s idea had merit and agreed to give it a go, however they might have crossed their fingers behind their backs. Gallagher’s system worked surprisingly well, and even more surprisingly he remained a popular man on the docks throughout his career, Irish jealousies notwithstanding. He ran the docks efficiently and kept his bargains, both with the men and the shippers. The vast majority of those who did business with him agreed “he was a fair man.”

\While the Gallaghers didn’t have a monopoly on brains or ambition, another man of that name also did very well in Cleveland. He came to be known as “Holy Water” Gallagher because of his penchant for nearly “drowning” the corpses he attended in his role of undertaker. Though there were no funeral homes in those days, the custom being to lay out the deceased in his bed or in the parlor, Gallagher’s services were required to prepare the corpse, hire the wailers, and see to it that the poor soul was sent off in splendid fashion. He and his business prospered mightily and he became one of the most prominent members of the Irish community.

He was, after all, one of them. When he arrived in Cleveland from Mayo in 1847 at the age of 19, Gallagher completed the transfer of the family from that wind-swept county to the banks of the Cuyahoga. His five brothers had preceded him here, as did his sister Mary, who had come in 1836. Gallagher landed a job unloading iron ore, but after paying the red dust its due for two years, he knew there had to be a better way to make a living. He saved his pennies and bought a horse and wagon and set himself up as an independent drayman.

Using his contacts, his brothers and cousins, Gallagher was soon established in a very successful hauling business. This bit of enterprise, he was to explain later, “Came from a bit o thinking on my part. Someone had to haul the cargoes the ships brought in, why shouldn’t it be me?” No doubt, he must have asked himself another question — Why aren’t there any Irish undertakers? He answered his own question by becoming one and giving up his profitable, but definitely plebian, hauling business.

Another Irish entrepreneur of the day was Captain Patrick Boylan, a descendant of one of the few men who escaped Cromwell’s slaughter of the inhabitants of Drogheda. Boylan’s grandfather and father were pilots in the harbor of the city of Cromwell’s revenge and, as a lad, he was introduced to the sea and its mysterious ways. He became a highly skilled seaman and crossed the Atlantic, first settling in New York in 1852. A short time later he negotiated the purchase of a sailing vessel and brought it to the Great Lakes, using Cleveland as his base of operations. If nothing else he did improve the morale of the Iron Ore Terriers, for it was a proud thing to unload a ship owned by an Irish Catholic, the only such ship afloat on the inland seas.

This was the decade of the Irishman striking out on his own, of attempting to establish his own business. Daniel Donahue, for instance, became the city’s first Irish Catholic dairyman, and his business prospered so well that he was able to purchase 600 acres of land on the far west side of town to increase his milk production. James Clements, who had come to Cleveland in 1843, founded a stone mason business. Peter Daly arrived in this city in 1848 and, though only 18 years of age, started his own hauling business. He, too, had paid his two-year dues as a teamster before making his move, which was solidified by a contract with the Cleveland Rolling Mill Company.

In the Cleveland area there were at least two exceptions to the Irishman’s distrust of land ownership during this era, Daniel Hoynes and James Hickey, both from County Kildare. The two men worked for the Big Four Railroad Company and saw in the land near Olmsted Township a great opportunity. Hoynes was the first to leave the railroad life. In 1847 he bought 600 acres of fertile Olmsted toil and prospered sufficiently to raise a family of 10 sons. Hickey left the Big Four two years later and purchased 1,000 acres in the same township. Both families were to remain tied to the soil for many years.

Shantytown Life in the Late 1800’s

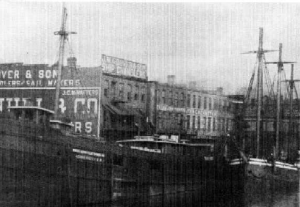

However successful the more daring and ambitious Irish were, the average man of the same community during the middle and latter half of the 19th Century still looked eagerly to the docks for his livelihood. It must be kept in mind that until the industrial explosion occurred in the 1870’s, Cleveland’s great wealth lay in its bustling port. Not only did it serve as a voluminous exchange center of commodities, but also as the Great Lakes’ largest builder of ships. For decades the harbor area was a veritable forest of masts.

The Irish who peopled Cleveland’s West Side lived anything but comfortable lives, and that includes those who regularly brought home a paycheck. Newspaper accounts of the day make much of the squalor that was Shantytown, but little of the fact that well into the 20th Century the Cuyahoga was an open sewer of industrial and human wastes. Disease was rampant and it was only a question of which disease would strike the Irish at any given time. Almost all the plagues emanated from the Flats area, the heart of Irishtown. The principal causes of death there were cholera, diphtheria, scarlet fever and diarrhea infantum.

The Irish dock worker received on the average $8 for his “26 dry days” of labor each month, hardly a considerable sum even in those days and certainly not enough to afford him the more readily available creature comforts, much less anything that could be considered a luxury. His shanties were, indeed, improving and were generally larger in size, thanks mainly to his skill as a liberator of lumber. Of course, that isn’t saying too much, when one considers that almost any edifice erected, say, in the 1850’s, simply had to be larger than a tarpaper shack or clapboard lean-to.

Many of the Irish, who had no place to build their shanties other than on the sides of the hills that sloped down to the Cuyahoga, displayed a certain amount of ingenuity by building homes on stilts. That way, one need merely plumb his floor and anchor his house against the hill, all the while increasing the length of his supports. Such open air basements provided children a great place to play hide-and-seek and wayward men a place to sleep off their night’s indulgence of spiritous waters. The mainstays of the back or side yard, as the case might have been, were the outhouse and the woodshed, with the latter also serving as a place of punishment for recalcitrant or otherwise obnoxious children. The Irish were not a race to pamper children in any given era and certainly not in the mid-19th Century, a time of harsh reality.

In a time when the Irish continued to stream into the city, adding to its seemingly perpetual housing shortage, the modest dwellings of Irish families were continually bulging at the seams. A typical family unit would include the father, mother and normal large brood of children, plus any surviving grandparents and down-and-out relatives many times removed. Sometimes, friends of distant relatives would be given places to rest their weary bodies. It didn’t really matter, the Irish had to take care of their own and they did, in the complete belief that there was always room for one more. Privacy, if it existed at all, was a state of mind and not a condition of reality.

There is a centuries-old adage having to do with the poor always being more generous than the rich, that the less people had, the more willing they were to share their meager goods. While this bit of philosophical thought has encompassed all nations from the earliest days of civilization, the Irish made it a truism. Sacrifice was the key to life on the banks of the Cuyahoga and that included one’s time and consoling words, as much as it did one’s loaf of bread. If any one expression came to the fore in Irishtown, it was the simple phrase “our own kind.” That said it all.

Meals for reasons both economic and by design, were simple and as filling as possible. For a people long-accustomed to near starvation diets, the overwhelming thrust of eating habits was to fill the stomach to the bursting point. The famed “Mulligan Stew” could serve as a prime example of a dish fitting the needs of a 19th-Century Irish Clevelander. It was made from the cheaper cuts of meat, potatoes, of course, and most any kind of compatible vegetable. The makings were thrown into a kettle and simmered until they took on a gelatinous form, the better to stick to one’s ribs. Corned beef and cabbage became synonymous with the Irish, and fish dishes were also favored, with tea as the primary beverage. The chicory-flavored coffee wasn’t too popular, milk, other than a mother’s own, was rightfully suspect (Louis Pasteur was yet to make it safe), and beer was for Germans.

Irish Saloons

There was, of course, another liquid that the Irish drank often and in large amounts. Most people called it whiskey, but among the Irish it was more commonly known as “the creature.”

That was only as it should be, for they saw in that amber-colored spiritous water an almost mystical being, one who had extraordinary power over the affairs of men. While it was true that “the creature” had a cruel streak in him, and woe to the man so foolish as to deny it, he was, in the main, jolly good company, a friend who could perform miracles with a man’s soul, often sending it soaring heavenward at a moment’s notice, to a far better place than most mortals knew existed.

Whiskey often has been called “the curse of the Irish” and few care to argue the point. All one need do to prove the validity of that statement is peruse the rolls of alcoholic treatment centers in major American cities. It is an experience not unlike reading a Dublin phone book and most of those unfortunate souls ended up in such centers as the result of taking just “a wee drop of the creature” once too often. Of course, a “wee drop” in Irish jargon usually means enough to drown a man of another nationality.

Indeed, the 19th-Century Irish loved their saloons. They would sit in them of many an evening and, spurred on by “the creature,” dream their dreams and scheme their schemes, all the while licking physical wounds gained in their labors and mental wounds, courtesy of the Yankee establishment. They would talk of the old country and sing its songs until there wasn’t a dry eye in the place. They would give Victoria Regina a roasting the likes of which she wouldn’t see this side of hell and gleefully predict that her fat derrière would one day be singed by the coals of that nether World. To hell with her Britannic Majesty and all the bloody Orangemen who ever lived. Up with the Pope.

That the Irish who huddled on the banks of the Cuyahoga had more than a speaking acquaintance with “the creature,” can be attested to by the fact that Whiskey Island, a relatively small tract of land, boasted 13 saloons in its heyday. Toward the latter part of the century in question, the Irish supported in generous fashion 24 watering spas that dotted the hill between the docks and St. Malachi’s Church, no mean achievement even for Irishmen.

While much has been made of the race’s fondness for and propensity to indulge in spiritous waters, most of what has been written has told, at best, only half the story. Few historians, and oven fewer social scientists, have done any probing as to the root cause of the drinking problem of the Irish, but then few such men have taken the time to study the painful history of Ireland. The Celts were a boisterous race and they loved nothing better than to attend a feis, a festive gathering of the clans, where much celebrating and merriment ensued.

The Irish drinking problem, however, had its roots in seven centuries of oppression, the most ungodly kind of rapine ever visited upon a race. There has never been a people who suffered so much for so long who did not develop or grasp an already existent mental crutch. The Irish reached for the liquid narcotic which had the power to make any day seem bearable, even if only for a moment or two. If the truth be known, spiritous water saved more Irishmen than it ever ruined, but, unfortunately, those kinds of statistics are never compiled.

It must be understood that in this country in the 19th Century, the saloon was much more than a place to go to forget ones troubles. It was everything to the Irishman, his social club, his forum to exchange philosophical thoughts, to engage in political debates, the stage on which he performed his theater magic, even his town hall platform. What better place could possibly serve him? None, of course, and the whiskey that flowed was merely a glorious fringe benefit.

Though they might be largely illiterate, the Irish in Cleveland, as in other cities in which they settled, were great writers of prose and poetry with their tongues. The saloon was an absolute necessity, because the Irish had to have someplace to let their soul feelings take wings, to prove they were capable of expressing artistic and noble thoughts. It is also quite true that the saloon also served as a dais for their collective rage and they vented their spleens in the direction of the Yankee establishment. That, it should be well noted, was about the only way an Irishman ever counted coup after a skirmish with the local natives.

It was, in fact, in the saloons that the Irish earned their reputation for being quick of mind and sharp of tongue. Some of the exchanges of wit have come down through the succeeding generations and have taken on legendary status. Of course, sometimes a man’s abrasive tongue would bring him back an argument in more solid form — like a fist exploding in his face. Bejayzuz! There were some splendid rows in those quaint forums of debate and many an Irishman woke up the following morning with two very distinct kinds of headache. They didn’t call police vehicles “Paddy Wagons” for nothing.

Again, it wasn’t only the whiskey that made the early Irish in Cleveland a rowdy bunch, but another trait that developed during seven centuries of fending off extermination — the need to be as devious as the given situation demanded. A young curate, who had spent years among them ministering to their spiritual needs, once observed:

Every Irishman who was ever born is two-parts saint and two-parts son of a bitch. An Irishman will finger his beads and talk ceaselessly about going to heaven, yet can never resist the temptation of scratching the nose of the Devil.

There are many who would agree with the good father’s assessment of the race, for who knows better than one’s own kind? Certain traits beget certain actions and over the centuries a collective national character is formed and hardened to the point of reality. It is eminently true that the Irish are not above bending a few rules of church or state, all the while being filled with pious thoughts about the Creator and all his lovely angels and saints.

If the Irish have any trouble with their faith, it’s only because they know it too well and are so fond of it that they feel they can deviate from its tenets, should a particular occasion arise. The Irish are firm believers in St. Francis of Assissi’s assertion that the body is a recalcitrant donkey that inhibits man in his quest for spiritual perfection. Sure, and it’s Brother Ass who prevents the Irish from being a phalanx of solid saints and nothing else. The Irish always have made up for their peccadilloes in a manner that can only be described as grandiose. Consider, for example, that at one time not too long ago, Irish missionaries comprised 27% of the Roman Catholic Church’s world evangelizers. What a staggering statistic that is a nation of six million souls supplying more than a quarter of all those who labored in foreign mission fields. In comparison, Americans represented 6% of the total number of missioners and, at that time, were some 40 million strong.

Politics

While the Cleveland Irish of the 1850’s might rage about their treatment at the hands of the established natives, they were quick to recognize a flaw in those Yankee “Swells.” The owners of the mills they worked in and docks they toiled on had, however begrudgingly, given them the vote. It would only be a matter of time until the Irish would overcome. The Irish saloons took on yet another function — it would be precinct quarters for the Irish who aspired to political office, the base upon which the famed Irish political machine would be built.

It is interesting to note that the Irish in Cleveland were rather slow to develop any real political clout in this community until after the turn of the century. Admittedly, they ran their own turf and often made a difference in a particular elective race, but they didn’t make the kind of splash that their brothers did in other large American cities. In New York, for instance, 18 Irish Catholics were elected to political office as early as 1852. In 1873, with the political demise of William Marcy Tweed, they took over Tammany Hall itself.

There were a number of reasons the Cleveland Irish political clout remained latent rather than becoming blatant. The foremost of which had to do with their numbers. The Yankees and immigrants from other nations were still the large majority. Secondly, the Irish were assigned the anathema role in society, the role blacks have been cast in today. The only other group of immigrants to give the Irish meaningful support were the Germans, who, although they thought the Irish improvident wastrels, nevertheless saw in them something charismatic. It is even more interesting to note that nearly a century later, when the Slavic peoples of Cleveland formed a group to oust the predominant Irish from political office, the Germans alone stood by them. But that is getting far ahead of the story.

Crime

The Irish profile, from the earliest days of their arrival until the turn of the century, was not one, which would lure Yankees to ballot boxes in their behalf. It must be remembered that all through the latter decades of the 19th Century, the Irish of Cleveland were blamed for every major and minor ill that afflicted the city. It was estimated by police officials and trumpeted loudly in all Cleveland newspapers, especially Edwin Cowles’ anti-Irish Cleveland Leader, that 90% of all crimes committed within the city’s boundaries were perpetrations of the Irish.

While that percentage seems exhorbitant, it must be acknowledged that there was a criminal element in Irish society that was an everyday grim reality of life. Since the Irish of the West Side were very much ghettoized, as the result of their own doing as well as that of others, the law-abiding Irish were the principal victims of personal crimes, while the Yankees were the victims of offenses against property. The latter received far more notice from the press than the former, but then, that was to be expected.

Newspaper accounts of the day and the oral history of the Irish community handed down through the generations are in general agreement that most of the crimes would fit into the categories known today as robbery and assault. Groups of thugs would roam the bawdier areas of Irishtown and waylay the careless souls they would come upon. The most notorious of those groups were the McCart and Triangle gangs, whose members plied their nefarious ways in the darkness of night, mostly pilfering goods from the docks and nearby warehouses. There were occasional murders of night watchmen and police, but crimes with attendant fatalities were not the usual occurrence.

The Irish community had a very strange attitude toward the criminal element that lived within it. Some historians have likened it to the “omerta” or silence of the Sicilian immigrants of the early 20th Century, but that really wasn’t the case. The Irish, with their heads full of fantasies, firmly believed there was such a thing as bad blood and those who robbed and mugged were the victims of that affliction. It goes without saying that they also thought that the bastards who preyed on the innocent would go to hell in a handbasket and be tormented for an eternity, so why should they get exercised about such wrongdoing?

A newspaper item of the early 1870’s revealed that however patient the Irish might have been with the criminals who lived within their ranks, they appreciated any discomfort that might come the evildoers way. One day just such a reward came when two gangs (unidentified) settled a territorial dispute by warfare in broad daylight. In no time, a large crowd of Irishmen gathered to watch the head bashing and cheered like mad when the going proved all but fatal to both gangs. The crowd also booed lustily when the police moved in to prevent what appeared to be certain mass murder among Cleveland’s citizenry.

The collective blood-thirstiness on the part of the lawabiding Irish who watched that and other melees usually dissipated by the time the brawls were over and known “bad bloods” were allowed to roam the streets unmolested. There were no vigilante groups in Irishtown, but that is not to say that individual acts of revenge were not carried out, for they were, sometimes in spectacular fashion. One “bad blood” was beaten to a pulp in front of St. Malachi’s Church as Mass was letting out one Sunday morning by an Iron Ore Terrier who had been waylayed by same outside a saloon the night before. Another bad blood was beaten, tarred and feathered and then heaved into the Cuyahoga by three staunch sons of a tugboat captain who had suffered a mugging at the hands of that culprit.

The crime in Irishtown, while real enough in itself, was, as mentioned, exaggerated by the city’s daily newspapers to the point where it seemed no one other than an Irishman ever committed a crime in Cleveland. At first, the anti-Irish publishers were content to detail the squalor of the Irish, but that soon became old hat, not to mention slightly embarrassing, when it was pointed out that not a single Yankee organization had ever offerred the struggling souls on the banks of the Cuyahoga so much as a drop of water to soothe their fevered brows. Dives was calling Lazarus a filthy pig. Squalor didn’t make for interesting copy, so when the crime reports started being issued, the newspapers quickly jumped on the bandwagon of Yellow Journalism. Cowles of the Cleveland Leader was a standout in the category of bias. His loathing of the Irish stemmed from the fact that he could not abide Papists, seeing in them a threat to this cradle of liberty. He was a strange man, for he had in his employ a number of Catholics whom he treated fairly in all regards. Individually, he could deal with them, but the thought of masses of Papists with the right to vote unnerved him to no end. He wrote violently anti-Catholic editorials in the Leader, in which he urged, among other things anti-Catholic in nature, that laws should be enacted to prevent Papists from holding public office in America. Of course, Cowles’ railings were to be expected, for at the time he was President of the Order of the American Union, an organization that had its roots in Know-Nothingism and was dedicated to the suppression of American Catholic civil rights.

The Irish had the book on Cowles, as they did on many another local newspaper publisher. They came to regard the press as just another tool of continuing oppression, a case of more numbers being done on their hard, flinty heads. The attacks on them only served to solidify their ranks and develop an “us against them” mentality that lasted well into this century. It also served to sharpen their collective sense of humor in regards to the local establishment. They were quick to seize upon and enshrine any putdown of the English-Yankee types who ran this or any other city or country.

When word came to them that the father of the noted Irish poet William Butler Yeats had squelched an English journalist, they repeated his words in every bar in Irishtown. For the record, the English newspaperman had asked Yeats Pere if the “Irish problem” would ever be settled? The reply was swift and rather devastating. Said the elder Yeats: “No, it’s insoluble. How can the dullest people in the world rule the cleverest?” So much for Irish coup counting in the 19th Century.

Service Occupations and Some Community Problems

One plus factor that resulted from the on-going Irish “criminality” was that the Yankee community decided that there was something in the adage about fighting fire with fire. Irishmen were invited to be official upholders of the law — to become policemen. A goodly number of them, weary of the work on the docks or some other less than commodious place, responded to the call and most of them did a creditable job. In fact, within a few decades, especially around the turn of the century, it seemed to America that every policeman in every large city in this country spoke with a brogue.

An almost equal number of Irishmen joined the fire-fighting brigades when they came to be formed, work every bit as hazardous as the policeman’s. In a city still largely consisting of wooden frame buildings, fire was a constant threat. Sometimes the Irish made the work doubly hazardous by making mad dashes to the scenes of fires just to get there faster than a rival firehouse. There was a spectacular fire in 1870 that engulfed a large section of the Flats, gutting warehouses, foundries and numerous Irish shanties. A pumper, manned by four Irishman, went careening down the Superior Road hill and into the river with all lives lost, including that of the two horses pulling it. No caution among the Irish once an alarm sounded.

If that weren’t enough for the Irish to handle, a short time later they were visited by an earthquake, one of the few measurable ones recorded in this area. Fortunately, it took no Irish lives, but it toppled their chimneys, rattled their shanties and caused them to wonder what could possibly come next. They didn’t have long to wait. The city fathers thought that the Flats would make an ideal location for a burning shed for the garbage that was collected daily. The refuse from the surrounding hotels, groceries and better homes was deposited in great piles on the river bank for observation by the Irish.

Though it was burned daily, the garbage did little to enhance the beauty of the neighborhood or improve the health of the people who lived nearby. The Irish took umbrage at this display of Yankee high-handedness and created such a furor that the city fathers finally discontinued the practice, opting to hire independent haulers to cart the unwanted decaying matter to less populous places on the outskirts of the city.

Continued Expansion: Lace Curtain and Shanty Irish

The 1870’s were to see the Irish spread ever westward, occupying most of the territory from the lake to Bridge Avenue, as far west as West 65th Street. It was called Gordon Avenue in those days and there wasn’t much beyond it, except for a few scattered farms. By 1880 a new parish, St. Colman’s, was created for the Irish who lived in that section. Thus, the West Side Irish had need for a third church although they were compressed into a territory only 40 blocks long by 20 wide.

By this time the Irish were getting numerous enough to create sections within their own enclave. They were also beginning to separate as to their degree of upward mobility. It was a time for labeling one another. When those who moved up the ladder of success more rapidly began moving into larger frame houses and taking on fancy airs, they were dubbed “Lace Curtain.” They, in turn, referred to there less fortunate brethren as “Shanty” or “Pig in the Parlor Irish.” There were yet other derogatory terms exchanged, some reaching back to events or conduct in the old country, which shows that the Irish felt a measure of success here. An especially insulting term was “Achill Irish,” which alluded to the supposed traitorous conduct of the people who inhabited that island off the coast of Mayo during the bad days.

Though insults were freely exchanged, the rival factions of Irishtown generally made no big deal of the jealousies that existed. There were, to be sure, occasional physical confrontations, highlighted by fistfights and the breaking of boards over one another’s heads, but nothing to get excited about, much less alter one’s way of living.

Of all the Irish who settled here, the most self-conscious were those who lived hard by St. Malachi’s spire. Taunted by the more affluent Irish, that is the ones who could afford curtains in the windows of their residences, the “Angle Irish” became the most chauvinistic of the Irish in Cleveland and by far the most resentful of having their turf invaded.

It was not uncommon for a “Lace Curtain” type, should he chance to meet a lass from “The Angle,” arrange to meet her in neutral territory, such as the corner of West 25th Street and Detroit Avenue. This was to be preferred to enduring real and imagined threats from the lass’ brothers, cousins and even unrelated members of the Angle fraternity. After an evening of courting, he would say his good night at that corner and watch his beloved disappear into the darkness.

While it may sound somewhat ungallant, it made a great deal of sense for two reasons — first, it saved him a possible beating and secondly, there was no need for him to accompany her merely for safety’s sake. No one in any section of Cleveland’s Irishtown could recall an incident of a woman being molested. Men were mugged and robbed, certainly, but a woman — never. It was the code and it was respected even by the bad bloods.

That is not to say that the Irish as a race were miraculously exempted from the fragility of man called concupiscence. They did commit sins of the flesh, as Whiskey Island’s bawdy houses attested, but the molestation of a “daycint” woman was considered the most detestable action of man and one of the deadliest sins it was possible to commit. The Irish view of carnality was almost the equal of the Puritans. Besides, to dispel passion they had “the creature,” which was, more often than not, up to the Job.

Chastity was a virtue held in deep respect by the vast majority of the Irish who lived here in the 19th Century, especially the latter half, and it was by no means meant for women alone. The men were expected to be equally chaste and no double standard would be accommodated — that was for Latins who couldn’t control their emotions and South Sea island pagans who didn’t know any better. Heaven only knows how many times that message came thundering down from a pulpit on high, complete with vivid descriptions of hell’s fires and the souls who would be tortured there for all eternity, all because they had fallen victim to the pleasures of the flesh.

Irish Wakes

As previously noted, the Irish were much concerned with the life hereafter, for they knew in their heart of hearts that a just God had to reward those who suffered their hell on earth, like many an Irishman did, or He would not be a just God at all. Many Irishmen dwelt so much upon their soul’s well-being that they often neglected their temporal welfare. They were caught up in philosophical argument — it really didn’t make a bit of difference what one did or did not accomplish here, eternity was forever. So let the fools and devils take all of earth’s spoils — life was but a brief encounter for the average Irishman anyway. If his work didn’t kill him at an early age, then certainly disease or pestilence would. Maybe even “the creature” might turn on him and send him to his grave.

That was, of course, the reason he took such an abiding interest in the celebration of death. The poor departed souls were finally in good hands, far better ones than ever cradled them here, and they could now rejoice for eternity with God and the heavenly hosts. Such an event as the passing of a good man or woman was proper cause for celebration, as well as for paying one’s sorrowful respects to the surviving family members. It took the Irish to come up with the most perfect combination of joy and sorrow ever invented — the Irish wake.

Out of respect for the deceased, may God have mercy on his soul, the bottles and merriment were kept in those parts of the house where he wasn’t. Any and all other rooms would be utilized because a wake made for a grand time for large numbers of people. The mourners, either familial or hired professionals, were considered no good if their keening did not drown out the noise coming from the other parts of the house. The wails that were emitted from the throats of the mourners were often of such heart-breaking intensity, of such soul-wracking despair that they chilled the blood of those present and sent them scurrying off to the anterooms where the spirits flowed like water from a tap. What’s more, a really good mourner could reach a peak of vocal desolation quicker than one could pour a drink, which added immeasurably to the ambience of the occasion.

The house of the deceased would be a study in black with ribbons of that color affixed to everything in sight, including the door knobs. All the clocks would be stopped at the moment of death and left in that frozen condition until well after the departed souls had been laid to rest. Relatives and friends would keep the vigil all night long or as long as they could remain upright, alternating their attention from the corpse to the back rooms. Conversation and laughter flowed as rapidly as the whiskey, with everyone in attendance expected to remark how good “himself” looked as he lay stretched out on his bed or in a casket in the parlor.

There were times when things got a little out of hand, when the bereaved’s friends would partake of too much spirits and decide that a practical joke was in order. On more than one occasion, the deceased was slipped under the bed and his place taken by a friend or relative. This was an especially effective ploy when the switch was made just before the professionals hired for the evening came in to view the object of their labors. No sooner would they begin their keening than the “corpse” would return from the dead by slowly raising himself to a sitting position and undertake a rapid blinking of his eyes. Needless to say, the mourners would flee in perfectly understandable terror. Such pranks caused a few fistfights now and then, but they were all done in the spirit of good clean fun and never failed as a conversation piece for months after.

The wake brought out one of the many strange quirks that are part and parcel of the Irish character. It seemed that the reprobate evoked a greater amount of sympathy from the gathered clans upon his passinq than the neighborhood saint. Call it the imp of the perverse or what you will, but there was something in the Irish soul that drove them to be more compassionate in their testimony to the scoundrel on his bier and to the members of his family. Such a passing brought out the last drop of an Irishman’s milk of kindness and warm comradeship was the order of the evening. Sometimes the pall bearers would even abstain from spirits, so as not to cause the surviving members of the family additional grief. God well knew they didn’t need any more, after having to put up with the likes of the deceased all those years.

Cleveland Irish During The Civil War

The Irish always have had quirks in their collective character. The local variety was to prove it beyond question in 1863, when a goodly number of them marched off to war and an equal number closed the port of Cleveland by staging a massive strike, a most unpatriotic action, to say the least. No amount of persuasion by the city fathers could bring the Irish to halt their strike that was supposedly denying their brothers the means to do decent battle with Johnny Reb.

The Irish, who were in on the founding of almost every labor union in this area, had picked a most propitious moment to stage such a strike. There were higher wages to be gained and the shippers could well afford them, seeing as how Cleveland was then “The Queen of the Lower Lakes,” the busiest port of any. The shippers thought otherwise and hired scabs from far and wide to replace them. While it seemed a sensible move, it never came off, because the Battle of Cleveland ensued and it took the entire police force of the city to quell the disturbance. The Irish stevedores had much the best of it, according to eyewitness reports, as they had a solid defensive position and “better throwing accuracy.” The age-old axiom of baseball held true — good pitching will always beat good hitting.

Besides, the Irish manning those barricades on the Cuyahoga were in no mood to apologize for their community’s efforts on behalf of the Union cause and the same was true of Irishmen in every city, North and South, in the country. What’s more, there were no draft riots here, as no one needed to be drafted. Cleveland’s Irish volunteered in numbers far larger than anyone suspected they would and they saw action on scores of battlefronts. To get an idea of how many answered Abe Lincoln’s call, all one need do is to study the list of names ofCivil War veterans inscribed on the walls in the display room of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument on Public Square. One-third of all naval volunteers from this area were Irish, which isn’t a bad showing, considering that they comprised only 10% of the population. Nationwide, over 200,000 Irishmen served in the Union and Confederate Armies and the division was roughly 140,000 to 60,000, with the North getting the larger number.

Organizations to Free Ireland: Trouble with the Church

The strangest quirk of all, however, had to do with the Irishman’s willingness to risk excommunication from his church by joining secret societies whose aim was the liberation of Ireland from English rule. Many of them did, in fact, accept excommunication from the church they so firmly believed in, because they considered the cause of their homeland’s freedom everv bit as sacred as their immortal souls. It was not an easy choice for most of them to make and an abundance of anguish followed every such decision to retain their memberships in organizations their bishops had condemned as “socialist-inspired and anti-American.”

No doubt, a bit of explanation is in order. It all began in 1858, when an Irish nationalistic revolutionary movement became a reality on both sides of the Atlantic. The heart and soul of the movement rested in two autonomous divisions of the revolutionary organization — a secret society in Ireland called the Irish Republican Brotherhood and an openly active branch in the United States called the Fenian Brotherhood. The American society, composed of both patriotic visionaries and embittered Immigrants was to be the fund raising unit that would supply the brothers across the tea with guns and other tools of war. The American Fenians also pledged to mount an armed expedition in support of the revolt that was to come.

Since the Catholic Emancipation Act had been passed by Parliament only a few short decades before (1829), the Irish bishops wanted no rocking of the governmental boat, especially by a group of wild-eyed revolutionaries. When Charels Stewart Parnell and others founded the Irish National Land League and encouraged the peasants to withhold rent from their landlords, the bishops, in return for certain favors by English government officials, condemned the plan as immoral — the peasants were guilty of thievery –– and threatened anyone so doing with excommunication.

The American bishops, with a few notable exceptions, followed the lead of the Irish hierarchy — the Fenians and Land Leaguers were to cease all socialistic, revolutionary activity disband their secret societies and concentrate their energies on becoming good Americans. Otherwise they would face excommunication, and that included all members in all such organizations. When the Land Leaguers of Cleveland informed Bishop Richard Gilmour that they saw no need to disband their Ladies Auxiliary, he, in turn, informed them that the ladies would be excommunicated as well.

The Irish have never been an anti-clerical people. They had shared too much mutual suffering with the clergy and had seen too many priests go to the gallows on their behalf for that. However, after the Irish bishops sided with the British government in the mid-19th Century, they lost their affection for men of that clerical rank. The kindest words the Irish accorded their bishops was they had to act as they did, lest the Church would have lost its government dole.

One of the reasons the Irish chose to disobey their bishops, both here and in Ireland, is that a considerable number of priests agreed with their assessment of the hierarchy and backed up their words by joining the secret societies themselves. The freedom of Ireland was at stake after seven centuries of foreign rule and oppression, so the bishops would have to give them a better reason to desist, than mere self-righteous words.

This is yet another reason the Irish here were delayed in their political development. A great deal of their energies were spent debatinq the plausibility of the Fenian movement, if not its efficacy, and there is no doubt that it was the focal point of action on the part of the more important local politicians. Though Americanization was already settling in, half of them remained Irish and Erin was on the threshold of gaining her freedom, so they thought. It would be another 60 years before the English Lion would withdraw his bloody claws from the heart of the Emerald Isle.

The dilemma facing the Irish here, of excommunication due to their participation in secret societies, was solved in the latter half of the 19th Century. The renians bungled their way to oblivion shortly after the Civil War ended, when they attempted to seize Canada and hold it hostage until Ireland was freed. An army of Fenians did invade Canada and captured Fort Erie for a brief spell before retreating back across the border into the waiting hands of the American army. The whole affair was rather comic and the Fenians fell from favor with the mass of sympathizers it had in the Irish communities across the land.

It was to give way to the Clan na Gael, an organization the American bishops didn’t like any better than the Fenians. In due time, however, the Clan na Gael was to give way to the Ancient Order of Hibernians, which, because of changes in the hierarchy and the soft-pedaling of its aims, came to an acceptable status. The Hibernians peaked here in 1900, when they could boast of having 13 full “divisions” ready at a moment’s notice to stage a parade for whatever occasion. Some proof of its acceptance can be ascertained in the fact that no less a clerical personage than John Cardinal Glennan of St. Louis was the organization’s national chaplain.

It was pretty much a case of what the bishops didn’t know would never hurt them. The Clan na Gael was, of course, as dedicated to the cause of Irish freedom as were the Fenians and its members had no intention of abandoning the fight, no matter what the American bishops might say. When they were declared anathema by the Church hierarchy, Clan na Gael members simply infiltrated the ranks of the Hibernians and held great sway within that organization Perhaps infiltrate is not the correct word, for the Clan na Gaelers were welcomed with knowing nods, if not open arms.

Irishtown: 1870’s and 1880’s

Yet another factor involved in the slow political development of the Irish here, and a very important one, is that most of the men and women who resided in the Irish ghetto were primarily concerned with bettering themselves materially, and thus were pursuing jobs with a little more concreteness to them. It must be remembered that the Irish in Cleveland really didn’t begin to make their collective climb until the 1870’s and 1880’s, when they began to move out of the mills and warehouses for better positions.

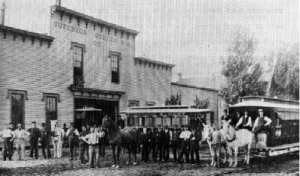

This period saw them become streetcar operators, independent haulers and, of course, members of the city’s safety forces in disproportionate numbers. The quickest-witted and more ambitious members of the Irish community sought white-collar work as soon as they mastered their numbers and learned to read and write. It is interesting to note that Irish women here were among the first of their sex to land jobs as clerks. During the 1890’s they actually outnumbered their male counterparts.

The Irish women were to play another role in the community of business and finance that was noteworthy. After a torturously slow acceptance as worthy workers during the 1860’s, they became much sought after as house servants in the mansions of the wealthy. In the 1870’s, Euclid Avenue ranked with the most beautiful streets in the world and the label “Millionaires’ Row” was one justly deserved. Along what is now between East 9th Street and East 40th Street, the rich built their massive homes, and in almost every one of those show places, Irish girls and women were serving, as they put it, “the Swells.”

Irish women were favored because they were quick to learn the ways of their “betters” and were passably to scrupulously clean. They were also generally loyal to the family they served and no threat to the lady of the house. They had learned their catechisms well and were tigresses when it came to upholding their chastity. Liasons with the men of the household were the extreme exception and not the rule. These women became maids, upstairs as well as down, seamstresses and, in some cases, managers of the household. They were to make a positive impact on those for whom they worked and, by doing so, contributed mightily to the enhancement of their own community.

What of that community in the 1870’s and 1880’s? It was still a grim one. The Cuyahoga, which flowed through the heart of Irishtown, became so polluted from the discharge of 25 sewers and the waste products of adjoining factories and oil refineries that the city health authorities formally protested its despoilment. The mayor, R.R. Herrick, called it “an open sewer through the center of the city.” Precious little was done, however, in the way of cleaning it up, and the Irish had to become accustomed to the smell.

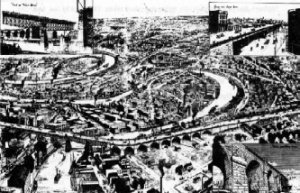

Irishtown at this time was a maze of cobblestone streets, huge piles of red ore and golden grain, and over it all wafted the smell of tarred hawsers and oakum. Factories and mills of every size and description hugged both banks of the Cuyahoga, and shanties had been erected up the hill all the way to St. Malachi’s Church, which served as a beacon of guidance to both ships and men.

Cleveland Irish in Baseball

A strange thing happened in the 1870’s in Irishtown that aided several score of its inhabitants to escape ghetto existense and see how the other half lived. It was a game called baseball, which had come into vogue after the Civil War and caught hold in Cleveland in the years shortly thereafter. A professional team was formed hereabouts called the Forest Citys, and, no doubt because a shillelagh was involved, the Irish took to it with a passion. In no time every brick-strewn lot in Irishtown was literally turned into a diamond in the rough.

While every Cleveland Irishman is acquainted with the feats of Paddy Livingston, who caught for 17 years in the major leagues, 11 with the Clevelands, not many realize that scores of Irishmen played professional baseball from the 1870’s well into the 20th Century. The pay certainly wasn’t good, but the fringe benefits, such as traveling about the country, sometimes as far west as St. Louis, and fairly good food, more than made up for the absence of money. Most important of all, baseball allowed the Irishman a chance to gain hero status, despite his national origin. He was accepted and it sure beat shoveling ore out of a boat.

The team representing Cleveland in the National Professional Baseball League in 1878, for instance, had six Irishmen in its starting lineup. ‘Big Jim’ McCormick was the premier pitcher and his fast balls were caught by one Barney Gillgan, who was described in one journal of the day as being “quick as a cat.” William Philips played first base, Tom Carey was at shortstop, William Reiley played left field and ‘Doc’ Kennedy was in right.

That was not bad for a group of lads who had taken the game up only a few years before. What was to become the American national pastime was already the local Irish pastime and would continue to be for many years. Many solidly Irish amateur teams existed until the 1930’s. Perhaps the last, and perhaps, greatest of them all were the Shamrocks of the 1930’s, a team managed by Will Dehaney, himself a professional ballplayer, and featuring the talents of his five diamond-talented sons.

Other Advances

The 1880’s gave birth to some marvelous mechanical inventions, all designed to speed up the wheels of industry. Among them were an electrically operated gantry, the predecessor to the ultimate unloader of ore boats, the Hulett, which exists to this day, and the newfangled open-hearth forge. Whereas the first mechanical unloaders, and there were several such inventions, could grab five tons of ore at a bite from the hold of a ship, the Hulett, which was to come to perfection in the 1890’s could grasp 15 tons in each of its two metallic claws. Furthermore, it needed only six men to operate it and could do in one day what it had formerly taken 100 Iron Terriers to accomplish.

In 1882 wooden vessels were giving way to those made of iron, and Cleveland was in the forefront of building the ironclads, “the ships that wouldn’t float,” and remained one of the most important shipbuilding centers in the nation. There were good jobs to be had in the shipyards, but they demanded skilled men. The Irish were to learn that lesson the hard way, as the shipbuilders began importing Scot craftsmen directly from the yards of Clyde.

However, things were looking up — there were always the ships themselves, and, of course, railroads were coming into their heyday. So much so, that there was literally no direction an Irishman could look without seeing the advance of the railroads. To the north, on the waterfront, was the Union Depot, 603 feet of solid Berea stone, with engines puffing in and out all day long. Those who lived down river at Irishtown Bend had the dubious pleasure of having railroad tracks in their front yards, the better to serve the mills even further south on the river. An anonymous Irishman, when asked what he had for dinner one night, supposedly said, “the usual — cinders.”