Part I: The Irish in Cleveland: One Perspective by William F. Hickey

Chapter 2: The Period of Emigration

With that historical background in mind, it is now possible to zero in on the long-suffering but ever rebellious people who immigrated to America and, of course, eventually to Cleveland. This background material is also supplied as a refutation that “the Irish had no history in the 18th and 19th Centuries,” which were the two principal periods of their immigration to the United States. Ireland had a history, but one many people would like to forget, especially British historians.

What is particularly sad about the period of their immigration to these shores is that it occurred, as we have seen, when the people of Ireland existed in quiet misery. It was their low point in learning, in the fields of arts and crafts and, most notably, in physical well-being. While it is a pity that it was not Columcille’s scholars who were coming here, it is even to the greater glory of those illiterate and impoverished Irishmen that they did so well once they established themselves here.

They came to America in such numbers that the extent of their migration boggles the mind. Consider the fact that between 1800 and 1900 over four million sons and daughters of Ireland crossed the Atlantic to begin a new life here. There has never been anything quite like it before or since, and it gives further evidence to the desperate condition of life in Ireland. As historian Carl Wittke put it: “It would be difficult to find another country where the causes of large-scale migration were so compelling as in Ireland in the 18th and 19th Centuries.”

It would not only be difficult, it would be impossible. Forgetting for the moment the Irishman’s hatred of his English oppressors and his even more intense hatred of the “foreign” religion they insisted he adopt, the average Irishman was fortunate to find any kind of work at all. When he did, he was paid six pence a day and one meal or eight pence with no meal. He lived in a sod hut of one room, which was perpetually cold, damp and filthy. More than that, he had absolutely no future in a land controlled and, for the most part, owned by absentee landlords. Little wonder he emigrated.

The First Irish Immigrants

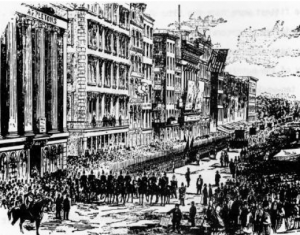

The first record of Irish on American soil, other than those unfortunate women and children who were sent by Cromwell to amuse the planters of Virginia, is marked in the log of the year 1654. Quite appropriately as things turned out, the Irishman’s entry to the new world was made possible by a ship called “The Goodfellow,” which deposited 400 of them on the docks at Boston. No doubt, they preferred the wilds of the unknown continent to their expected treatment at the hands of Cromwell.

The occasion of the landing of this “horde” of Irishmen sent the Yankee natives into a state of outrage and they immediately called for laws that would prevent a repetition of what had occurred. No welcome mat for the Irish in America, but then, what else was new? They weren’t even welcome in their own country, so there was no point in going back. They were here and they intended to stay, no matter how the Yankees felt about it; stay they did, despite the continued railing of the Bostonian proper and otherwise. They clung like so many barnacles to the wharves and pilings along the waterfront. To say that they prospered would be to stretch truth to the breaking point, but they did multiply, and 83 years after setting foot on American soil, they staged the first St. Patrick’s Day parade this country ever witnessed. Needless to say, there has been a Paddy’s Day parade down Boston’s streets since that eventful March 17, 1737.

From the time “The Goodfellow” first “greened” America, the Irish came steadily to these shores. They did not come in large numbers like their brothers of the Famine, but in a trickle. The nation’s first census in 1790 showed that 44,000 Irish lived here. Enough numbers of them had taken root by the time of the Revolutionary War that their presence was felt, and appreciably so by the colonists opposing the dictates of George III.

Students of history should be aware that the most common surname in the Continental Army was not, as one would imagine Smith or Jones, but Kelly. There were, to be exact, 696 men named Kelly in the ranks of George Washington’s inelegant but feisty army. What contribution did they make? Let Washington’s adopted son Custis tell it:

The aid we received from Irish Catholics in the struggle for independence was essential to our ultimate success. in the War of Independence, Ireland supplied 100 men for every single man by any other foreign nation. Let America bear eternal gratitude to Irishmen.

America, of course, was not quite ready to go that far, for the Irish were, after all, Papists to the core and therefore a threat to the nation’s pursuit of liberty and Protestant approach to life. The Irish would bear watching, and the best method of facilitating that would be to keep them in their place — in the inner city ghettos. The Irish, with enough exceptions to prove the rule, kept their place. They also kept these things close to their hearts, and the collective organ continued to smolder.

The conditions under which the Irish lived in the larger cities along the eastern seaboard were nearly, but not quite, as wretched as those they sought to escape from in their homeland. It was a cruel case of poverty and disease, followed by more poverty and disease. There was no work too menial for them to do and they did it. Despite the dreadful day-to-day existence they suffered, they saved what pennies they could and sent for brothers and sisters back in Ireland. That action alone gives one a remote clue as to what life was like in that “Little Black Rose of a Country” across the sea.

The typical Irish boarding house was a brick building three to six stories high that was filled “with runners and shoulderhitters” that preyed on the inhabitants. These ruffians, who worked out of the mandatory grog shop on the first floor, all spoke with brogues and spent their days either flim-flamming or strongarming the vulnerable newly-arrived. Yet life was still better here than at home.

Those just off the boat would be taken to one of these tenements and afforded space in the basement or “bag room.” Whole families would be piled atop one another in these dank cellars until death or some other horror emptied a room upstairs. Then the newly-arrived would be allotted one room that, more often than not, would be without ventilation of any sort and would reek with the stench of the previous family’s filth. Welcome to America.

A New York cotton buyer, who had just returned from a trip through the South, wrote in 1801: “The Negro slave on the plantations of the South lives under better conditions than most of the Irish in New York. He is also treated more kindly.” However true that might have been at the time, the downtrodden Irishman of the big city ghetto had a lot more going for him than the slaves in the South. Foremost, he was a free man, free to move about whatever his economic deprivation. Thus he was allowed to struggle, and that is all the Irishman ever wanted out of life. Let all the cotton buyers in New York lament his condition, the Irish were no slaves.

Besides, the Irishman had his first–floor grog shop where he could gather with his friends and display his sense of humor and social amiability, “shoulder-hitters” or not. Every such “Little Dublin” had social clubs that were usually given names that showed the Irishman was well aware of his status in the new country. There were, for example, a good number of clubs with the title of “The Far Downs.”

Mass Migration

The first sizable immigration to America came in 1816, when 9,000 Irish men and women made the crossing. In 1818, when the number doubled, vessels began to be chartered specifically for the purpose of transporting Irish immigrants. They came to be sorely needed, because by the year 1832 some 65,000 souls boarded them, heading for these shores.

Often these Irish were debarked in Canada, either at New Brunswick or Quebec, since many of the first waves of Irish came on Canadian lumber ships, the owners of which saw in those Irish bodies a suitable return cargo. It was profitable for both parties — the ship owners made money and the Irish found it an easy matter to enter the United States. It wasn’t difficult to walk across the border, and the Canadian debarkees soon gave New England a Celtic look. In a few decades they would take control of the once Yankee stronghold.

It should also be noted that the mass migration of Irish was more than welcomed by the English, both at home and in Ireland. They saw in that movement a lessening of the “Irish problem.” One London newspaper ran an editorial headlined “Good Riddance,” which went onto say that “the departing Irish were marauders whose lives were profitably spent in shooting Protestants from behind hedges.” It went on to describe the emigrants with such choice words as “vermin,” “snakes,” “scum” and “demons of assassination.”

The emigration of the Irish, while steadily increasing after 1830, exploded during the years of the Great Famine. It began in 1845, when an unusually cold and wet winter, followed by a like spring, created the conditions for a blight of the potato crop throughout the land. Since the Irish diet consisted mainly of two foods, potatoes and fish, the failure of the potato crop left the inhabitants little choice but to emigrate.

In 1847 a young English Quaker, who had gone to the city of Westport to aid the stricken Irish, wrote: “It is a strange and fearful sight, like what we read about in history books of beleaguered cities; its streets crowded with gaunt wanderers, sauntering to and fro with hopeless air and hunger-struck look, a mob starved and almost naked.” The sensitive young Quaker was fortunate that he did not tour the Irish countryside, for the sights there would most certainly have done damage to his psyche, especially the thousands of green-mouthed human corpses who had been reduced to eating grass to still their pangs of hunger. If that weren’t enough, the sight of men picking rotting flesh off the bones of their dead neighbors would surely have done it.

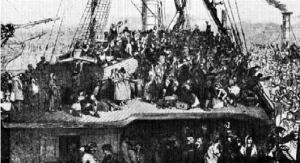

Just a glance at the passage figures of the Irish fleeing the Famine reveals the sharp increase in emigration. In 1846, 92,484 boarded packets for America. In 1847, 196,224 followed. In 1848, the number dipped to 173,744, but rose sharply the next year, when 204,771 left their native soil. In 1850, the last of the years considered to be a part of the Famine, 206,110 men, women and children made the crossing. In addition to those who came to these shores, untold thousands of others made their way to Australia, New Zealand, various South American countries and even to England itself.

One can get an idea of the hazards Of crossing the Atlantic, which were willingly faced by millions of Irishmen seeking freedom from want and oppression, from a letter written by one who had made just such a journey. In 1848 John Holland wrote:

Our ship was 10 weeks on the seas from Queenstown to Gros Isle, an island that lay below Quebec City, which is used as a quarantine center. Out of a total of 225 passengers, only 35 set foot on shore. The rest found their grave in the ocean, my two brothers among them. I have been told that 12,000 Irishmen have died at Gros Isle this year alone.

While the mortality rate on John Holland’s ship was well above average, deaths from disease, which spread lightning-like among the Irish in the fetid holds, often claimed half of those who boarded ships in English and Irish ports. The men, women and children in those holds were generally in a weakened condition to begin with and they had no medical help aboard ship. Often, they did not even have the comforts of the dying, as priests were scarce and those at hand greatly overworked. There were simply not enough hours in a day to administer the last rites to the multitudes needing them.

It was, of course, a case of survival of the fittest and the fittest were none too fit. A lifetime of deprivation, culminated by several years of actual starvation is not exactly the best preparation for a mid-19th Century sea voyage. That any of the nutritionally-deprived Irish survived those tight to ten-week crossings is testimony to the ongoing resourcefulness of the human body. Nor should the strength and attributes of the mind be discounted in any way, for the mental anguish expressed by the incessant keening over the loss of loved ones was only the tip of the Irish iceberg of sorrow.

If it weren’t for the intensely held faith of those suffering souls in steerage, not one of them would have been able to exist this side of madness. Despair, that black whore of the soul, was ever flitting about those in the holds, but their belief in the teachings of their Church held that seductress at bay. “Christ crucified,” they chanted, “May our crown of thorns be enjoined with Yours.” While certainly a lament, the ejaculation was also a rallying cry of sanity among the Irish voyagers. One of the principal reasons the Famine Irish preferred America to the British Dominion lands, aside from the fact that many of them had relatives here, was that they remembered it was American ships that brought what little relief there was to Ireland.

Irish Catholics in New York City, for instance, sent $800,000 to their native country in 1846 alone. It should also be noted that a number of Protestant denominations in this country made contributions of money and foodstuffs to the stricken Irish, something the starving people of Erin were not likely to forget.

Moving West: The Erie Canal

Whatever their penchant for long-suffering, the ghetto Irish came to realize that they had to leave the rat-infested tenements in which they dwelled, in order to survive. The death rate among them was horrendous even for those days of primitive medicine, but even more than that, they had no future in a place where a dozen men applied for every job that opened up.

The Irishman’s first chance to escape the ghetto was provided by a man named DeWitt Clinton, who as Governor of New York, championed the cause of the Erie Canal and turned the first shovelful of dirt himself in 1817. The Erie Canal, a dream 368 miles long, stretching from Rome, New York, on the Hudson River to Buffalo on Lake Erie, a bridal ribbon of water that would marry the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes afforded the Irish of the eastern seaboard a chance to push inland, to breathe fresh air. Later, the expansions of the railroads would do the same for other Irishmen, but for now, the Canal would suffice.

The Irish in New York and from as far away as Boston and Baltimore came pouring out of their tenements at the first sign-up call. So many were to follow the original 3,000 signees that they made the digging of the big ditch a private Paddy affair. The work was back-breaking, the pay low and the living conditions poor. So what else was new? A job was a job and the Irishman couldn’t afford to be choosy.

As noted, there were so many Irishmen involved in the digging of the Erie Canal that all the canal workers, whatever their national origin, were called either “Longfords” or “Corkonians,” depending upon from which area in Ireland the majority of the workers in a given encampment came. According to one digger, however, there was one plus factor about the work — it was the first time an employer in America hadn’t lied to an Irishman. The work, indeed, was back-breaking, the pay low and living conditions poor.

Just clearing the adjoining towpaths was difficult enough, but the digging of the canal itself was something else again. The Erie was an ambitiously planned ditch. It was to be 40 feet wide at surface level, sloping to a width of 28 feet at the bottom of its four-foot depth. When one fashions such a ditch 368 miles long, it means that a great deal of dirt has to be moved megatons of it.

Conditions for Canal Workers

In return for their labor, the canal diggers received 30 a day for 12 hours on the job, plus board and lodging. The board consisted of coffee and hardtack, with a little sowbelly (bacon) for breakfast, a lunch of bacon, bread and beans, and a dinner of stew, in which the potatoes outweighed the meat. While the meat was often maggoty, the potatoes were always good and what more could an Irishman ask for, other than a good jigger of whiskey at day’s end. Whiskey was, of course, part of any labor contract involving Irishmen, even those negotiated in the cities.

As far as the lodging was concerned, the diggers were provided with army tents, circa War of 1812. It was true the tents were of good size, but they were hardly comfortable, especially when a dozen men were crammed into each one. The canvas abodes were suffocating in summer and icebox cold in winter. In spring it was said that a man could easily drown in one. But oh, those lovely autumn days, those golden, hazy days of late September and early October — they made life worth living.

The Westward-Ho Irishmen soon discovered it was not the wear and tear on their back muscles that was dangerous, but the wear and tear on their insides by creatures they knew nothing about. They were called microbes by the people who knew about such things, and very few people did. Those invisible creatures came to be highly respected, if not feared, for they disabled more Irishmen than all the lower back spasms ever suffered by men the world over.

The deadliest microscopic foe was left by the mosquito, that pesky creature whose sacs dripped with malaria juices. There were, of course, no men the likes of Colonel William Crawford Gorgas, who eradicated the yellow fever among those who dug the Panama Canal in the early 20th Century. The Irish were left to their own devices — a daily jigger of whiskey and rosary beads. Sad to say, neither proved adequate for the occasion and hundreds of diggers went to their eternal reward at an early age from the banks of the Erie Canal.

The second microbic foe caused diarrhea, which while not as deadly, was nevertheless debilitating to an extreme degree. There is simply no way a man can perform hard labor 12 hours at a stretch if his intestines are water-logged. There is an accompanying weakness, not only of the body, but of the mind that prevents a man from exerting his will. Most of the contractors on the Erie Canal, good Christian gentlemen all, could not see the necessity for paying wages for no work. They opted to dock a man’s pay, rather than get caught up in Christ’s parable about the workers in the vineyard.

Chief Engineers Office Chesapeake & Ohio Canal;

Cleveland, 19th April, 1880.

To the Contractors for the Completion of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, Their Agents, and Sub-contractors.

You are directed not to employ upon your works any of the following named persons, viz: —

Lawrence Burns, mason

Richard Keefs, stone cutter

Nicholas Huges, stone cutter

George Biggs, stone cutter

James Mulligan, stone cutter

Henry Carter, mason

Dennis Nolan, mason

Jeremiah Reide

Lawrence Swift

John MeSweeny

Thomas Nugen

John McGinty

Edward Conner

James Watson

Michael Keenan

Patrick Murray

Michael Cunningham

Martin Rudy

Patrick Bannan

Petrick Murray

Peter Lavelle

Huge McCaffry

Edward Riely

Mark Kilroy

Patrick Roach, and

William McCormick

Charles B. Fisk, Chief Eng.

Blacklist of Workers, mostly Irish, On the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal

There was yet another microbe who regularly visited the canal sites, whose sole purpose of existence was to disrupt the Irishman’s work habits. It was the germ latter-day physicians would label diplococcus pneumoniae. About 75 varieties of pneumococci are known, and the Irish working on the Erie managed to catch most of them. Admittedly, bouts with this germ tended to be seasonal affairs, mostly in the winter and early spring, but they were serious enough to send many a Paddy to his grave.

Statistics, at their very best, remain boring. Numbers of Irishmen who died while digging the Erie Canal are boring, for they are merely numbers. The mind, in fact, can accommodate any number or series of numbers of deaths and other tragedies. It is only when those stark figures are personalized that the mind feels uneasy. One worker, Timothy Geohagan by name, wrote to his sister in Ireland, telling her of his life and job in the brave new world. “I don’t know, dear Sister, if any of us will survive, but God willing, we will live to see a better day,” he wrote from his tent near Utica in 1819, “Six of me fmiltentmates died this very day and were stacked like cordwood until they could be taken away. Otherwise, I am fine.”

What is remarkable about the letter is that Timothy Geohacan got someone to write it for him and some historian to punctuate it. Although the canal diggers were largely illiterate, they provided those who could write a steady source of income, for letters from workers streamed across the Atlantic. One such hired writer wrote the following to a friend:

I was writing a letter for this poor Paddy and the Paddy wants me to tell the folks back home that he has meat three times each week. When I asked why he wanted me to write that, seeing as to how he got meat three times a day, the Paddy told me that his folks would have a hard enough time understanding him getting meat three times a week and would think he had gone daft if he told the truth.

Though an inordinate number of Irishmen died beside that 368-mile stretch of water, their passing was no more than a ripple in the construction sea that was the Erie Canal. No sooner would an Irishman be buried in a shallow, unmarked grave than two would apply for his job. In other words, while it might have been a watery trail of tears for some, it was equally a stream of hope and ambition for others.

It is interesting to note that during the two years before the Erie Canal was completed in 1825, the main topic of conversation among the Irish who labored on it was that a new canal was rumored to be in the making. Best of all, it was to be in nearby Ohio country and almost as long as the Erie, which meant at least eight years work with steady pay and no questions asked about one’s ancestry. Things were looking up for the survivors of the first big ditch.

The Ohio Canal

It was, of course, no accident that the digging of the Ohio Canal commenced the same year that the Erie was completed. There were all kinds of wrangles among members of the newly-formed Ohio legislature as to its route through the state, but in the end the start of the canal depended primarily on the availability of men to dig it. In the summer of 1825, upwards of 3,000 Irishmen, all skilled with the shovel, were standing by, just waiting for the sign-up call. It came on July 4th of that year, when the first ground was broken downstate near Newark.

The Irish, veterans of the Erie and a goodly number just off the sailing ships, made their way to almost every point of the proposed route the 308-mile canal was to travel between Cincinnati on the state’s western boundary and Marietta greenhorn would find his final resting place along the banks of the Ohio Canal.