Part I: The Irish in Cleveland: One Perspective by William F. Hickey

Chapter 1: A Brief History of Ireland

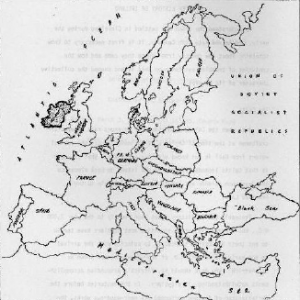

To understand the Irish who settled in Cleveland during the early, middle and late 19th Century, it is first necessary to know something about the country from whence they came and how the centuries of troubled existence on that island shaped the collective character of its peoples.

The Celts

Just when the Celts, a considerably advanced race of warrior craftsmen at the time of Christ’s birth, moved across the channel waters from Gaul is not known with any certainty. What is known is that Celtic legends relating to the island go back almost to the days when Abraham was leading the Chosen People to the Promised Land.

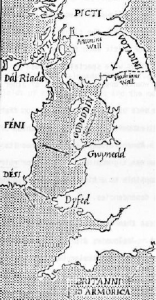

Traceable Celtic history dates back roughly to the year 2,000 B.C., but for reasons purely romantic, most scholars have tended to set their historical timetables to coincide with the arrival in the early 5th Century A.D. of the man who became known as St. Patrick. Why this should be, Patrick’s astounding accomplishments notwithstanding, is a mystery. In the centuries before the Christianizer of Ireland performed his near-wondrous works, the Celts had established themselves as overlords of Britain and Gaul, as well as the island of their real destiny.

Their strength in numbers and skill in battle enabled them to range far across the continent of Europe. Indeed, their war cries rang through many an Alpine valley, including those that now form parts of northern Italy and Yugoslavia.

Their success on various fields of battle stemmed from their advanced status as craftsmen as much as it did from natural ferocity. The Celts’ finely-honed metallic axes scattered the Teutons and others unfortunate enough to get in their way. But it was not only a case of superior numbers and arms winning the day, however, for the Celts were a thinking people, capable of instituting and altering battle plans as the occasion demanded. We can glean this from the very word by which they came to be identified — Celtoi, meaning “the clothed people,” indicating they considered themselves superior to the naked Teutonic tribes that sought to share the continent’s western regions with them. In other words, the Celts had long given up the practice of painting themselves blue and hanging naked from trees.

By the time Caesar’s legions invaded Britannia, civilized society in Ireland was already ancient, at least as advanced as the Greeks and, in many ways, similar to the heroic life Homer so notably recounted in his epic tales. Like Greece, Ireland possessed an honored class of bards, men who were categorized into sixteen divisions and whose astonishing memories could store away thousands of verses of romantic narrative. The bards were veritable walking libraries.

The core of Celtic society was the clan. Traditionally, all members of a particular clan were related and bore the same name. As their learning and skills developed over the centuries, other names began to surface within the clans. The name Hickey, for example, came from the Celtic word for healer. We can assume that the ancient Hickeys were specialists whose skill was the dressing of battle wounds and the treatment of other maladies.

Normally, the size of the clan was based on fighting strength, with each such unit expected to field 30 companies of 300 men — the equivalent of a Roman legion. Each clan had its ri or king, and above the clans was a group of over-kings or ruiri, who, in turn, were responsible to a high king, who held sway over all of Ireland and its dependencies.

It would be less than truthful to say that Celtic society was without blemish. Jealousies did exist between over-kings and among clans, and many spectacular battles were fought. However, more often than not the clans lived in reasonable harmony, drawn together by their common basis of language, culture and code of laws. Traditions were so strong among the Celts that internecine warfare could be halted by the high king declaring a period of national festivity.

The Celts, also like the Greeks, early on in their history abandoned their primitive form of religion and adopted a number of native divinities, thereby launching the relatively sophisticated era of Druidism. For centuries the Druids were the elite members of Celtic society, the soothsayers, magicians, and repositories of all learning in the days when no man on that island could write.

Saint Patrick

Thus, into such a land, already comparatively advanced in the material fields of arts and crafts and the metaphysical field of religiosity, came the influence of Christianity, whose outstanding representative was the aforementioned Patrick. Though it is not generally known, there were Christian settlements in Ireland even before Patrick was held as a slave there, but they were confined to the southern tip of the island and were of little consequence.

While much has been written of Patrick’s escape and subsequent triumphant return to the island, a good deal of it has been romanticized to the point of absurdity. What he accomplished needs no adding to, for his deeds have come thundering down through the centuries on their own merit. History, however, demands an accounting without flowery froth.

Whatever his personal gifts or his ability as a proselytizer, Patrick was, above all else, a very practical man as he went about his self-appointed task of converting the Celts to Christianity. Having been held captive by them for six years, he knew their language, their customs and their peculiarities of character, and he used this knowledge at every opportunity.

The bell is supposed to have been taken from St. Patrick’s grave in 552, at which time it was placed in a shrine. The bell is of thin sheet iron coated with bronze, and it has an iron clapper. The bell is known as the Bell of the Will. Nothing remains of the original shrine; the present shrine was ordered by the archbishop of Armagh sometime between 1091 and 1105. The shrine can be dated this precisely because the name of the archbishop and of the high king of Tara are given in an inscription in Irish on the back panel.

His overall strategy to win their minds and hearts was as sound as it was simple. He went straight to the rulers, the ri and the ruiri, with his message of the Good News. Knowing their penchant for debate, he engaged in near-endless exchanges of thought, all the time remaining the friendly persuader. At length, he convinced them of the validity of his teachings and, once that was accomplished, he further induced them to lead the way in spreading the Gospel of Christianity throughout Ireland. Then he merely stood back and collected the clans like so many sacks of ripe grain.

That he was one of the Church’s most remarkable men goes without saying, for what better attests to that fact than his conversion to Christianity of a warlike nation of people without the spilling of any measurable amount of blood? It must be noted, however, that Patrick did not live to see his work completed. It took another full century following his death in the late 5th Century to rid Ireland of its last vestige of paganism.

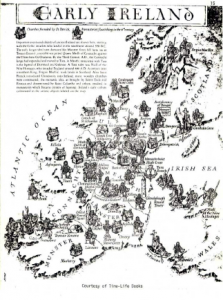

Interestingly enough, this famed missionary left no personal monuments. What he did leave proved to be a far more glorious testimony to him than all the monumental bric-a-brac might ever have been: he left the Church firmly established in Ireland, and that institution soon began creating scholars the likes of which the world has rarely seen. It was these followers of Patrick who became the saviours of Western civilization and culture for a period of almost four centuries, while mainland Europe foundered through the Dark Ages.

Irish Scholarship and Missionary Work

This period was easily the most magnificent in Ireland’s long history in terms of recognizable accomplishment. Accredited historians have come to a general agreement that it was these Irish scholars who kept the lamp of civilized learning burning brightly, while those of Rome and Byzantium dimmed to a flicker.

Nor did the Irish scholars content themselves with mere acts of knowledge preservation, for whenever the heathen storm raging over Europe subsided in the least, they would come pouring out of the island’s monasteries and launch their fragile ships in an easterly direction. To all parts of Europe they travelled, urged on by Christian zeal and the knowledge that they alone were the repositories of civilized life and learning.

The magnificent Columcille, who was by birth a king but chose to become a saint, was only one of Ireland’s leaders in missionary work. From his fortress on the island of Iona went scores of teachers and preachers who ultimately restored Christianity and civilization to the continent. Clement went to Gaul, where he was to tutor Charlemagne, Boniface went to the land that became Germany, and Gall became the Apostle of the Swiss. These are just a few of the better known ones, but there were so many it is probably unfair to name any without naming them all. Let it suffice to note that in Germany today 55 Irish saints are venerated, 45 in France, 30 in Belgium, 13 in Italy and 8 in Scandinavia.

Irish scholarship during this period was considerable by any standard. St. Simeon the Stylite was not content to teach advanced mathemetics in the usual manner, but preferred to do it by verse. Virgil of Carnolia insisted that his mathemetical computations proved that the earth, of necessity, must be an orb. Brenden the Navigator immediately set sail to test that theory and, by so doing, added substantially to man’s knowledge of geography.

The Norman Invasion

Ireland’s centuries of glory, alas, were to come to a bitter end, so intensely unpleasant, in fact, that it is almost without precedent on this earth. While some historians trace the woes of the Irish to the Viking incursions of the 8th and 9th Centuries, history does not support their collective thesis. It is true that the Norsemen were successful enough in their repeated invasions of Ireland to establish permanent settlements attempt of the Vikings to expand their sphere of influence. The coastal settlements were never more than a blemish on the face of Ireland.

It wasn’t until the Norman invasion of 1171 that the Celts first tasted the butterness of wholesale military defeat. Ironically, Ireland’s downfall was, for all practical purposes, brought about by an Irishman. It all began after a dissolute brute of a king, Dermot Macmurrough, was chased out of Leinster for ravaging the fair wife of the Lord of Brefny. Tought she apparently did not mind the ravaging, her husband and his clansman did, and Dermoy was forced to flee the country. He ended up in Acquitaine, where he won the favor of Henry II, who seized upon Dermot’s grievances as an excuse to utilize a Papal bull of authority over for ravaging the fair wife of the Lord of Brefny. Though she apparently did not mind the ravaging, her husband and his clansman did, and Dermot was forced Ireland that was given to him by Pope Adrian IV, who was the only Englishman ever to sit on the throne of Saint Peter. For the record, his name was Nicholas Breakspeare.

Henry induced two of his barons then residing in what is now Wales, Richard de Clare and Earl Pembroke, the famed “Strongbow” of history texts, to launch an attack on the Emerald Isle. The Normans came on horse and foot, their suits of armor gleaming in the sunlight, their guidons flapping in the coastal breezes and their vast array of modern weaponry combining to form an awesome spectacle. Now it was the Celts’ turn to feel the despair attendant to facing a foe with superior arms and greater manpower.

Though the first flush of victory rested easily on the Normans, they found holding onto their conquests quite another matter. While the Celts might have been routed, they displayed a remarkable talent for regrouping quickly. What’s more, they also displayed a tenacity of will that let the extravagantly plumed Normans know that the subjugation of Ireland would be no easy task, but rather a long and costly one, paid for in rivers of blood.

Adding to the woes of the conquering Normans, jealousies soon erupted within their ranks. More accurately, Henry II became annoyed by the less than grateful attitude of his newly rich barons and ordered them home for an accounting of the spoils. At the same time, the remnant Viking settlers rallied to the cause of their former foes, the Celts, and joined them in their incessant guerilla warfare, an art the Irish were never to forget.

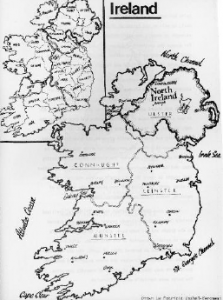

This was all too much for the proud Henry II to bear, so he led a mighty army across the Irish Sea, determined to subjuqate all the wild men who inhabited the island, no matter what they called themselves or from whence they originally came. Henry’s army made that of his barons look like a scouting party. The Irish chieftains, stunned by this show of Norman strength, particularly by the quality of the armament, sued for peace. Not all of them, of course, for that would have meant forsaking the national trait of ignoring overwhelming odds in a foe’s favor. Rory O’Connor, the high chief of Ulster, refused to surrender to the Norman usurper and put up such fierce resistance that Henry II was content to hold only Leinster and Munster.

Lessening English Influence

However, even those two provinces were soon to slip from his grasp. Henry II helped this come about with his complicity in the murder of Thomas ‘a Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury. His return to England to face a Papal Inquiry set in motion a debilitation of the Normans left behind. They began to lose their identity as conquerors and began an assimilation of Irish ways. They soon, in fact, were absorbed by the people they had so recently conquered.

This occurred, one might note, in spite of Henry’s stringent laws designed to prevent that very possibility. For instance, the penalty for a Norman fraternizing with the Irish was rather severe. Anyone caught so doing was to be “half-strangled, then disembowled while still alive,” and woe to the hangman careless enough to break a neck, thereby allowing the perpetrator of such a crime a relatively merciful death.

Incredible as it might seem, despite that law and others equally formidable, the Normans continued to take up Irish ways, to the point where they adopted the native dress, language and names, not-to mention the principal cause of all this — to take Irish wives. In a relatively short time the barons and lesser rank Normans were so transformed that they actually aspired to become Irish chieftains.

The government in England naturally took a dim view of the Norman turn of character and in 1295 issued yet another decree forbidding such goings-on. Not only was the statute published in vain, it served a purpose directly opposite its intent — it hastened a series of self-defense alliances among the Norman-Irish chieftains and the traditional Celtic leaders.

The seduction of the Norman overlords continued unabated in the ensuing years and the people in Ireland gained a respite from English interference in their affairs, thanks largely to certain events which distracted the English considerably — The War of Roses between the houses of Lancaster and York, to mention one. In fact, at the time Henry VII assumed the throne, English influence in Ireland was limited to the County of Dublin and parts of Meath, Louth and Kildare.

The ascension of the seventh Henry to the throne marked three centuries of English rule in at least some parts of Ireland and, all things considered, the whole effort was a stand-off. While Norman banners did, indeed, float over the Irish countryside, the pride paid in blood and defecting sons was a princely one.

In 1494 Henry VII determined to do something about the Irish problem once and for all time. He decreed from that moment to perpetuity, English law would be the operative one in the land and, needless to say, the Irish code of laws would henceforth become inoperative. This action only served to stiffen resistance and inspire rebellion anew. The dismayed Henry VII decided that the damnable island was not worth the trouble of subjugating it and appointed the Earl of Kildare to rule it as he saw fit.

Unfortunately for Ireland, Henry VII’s successor, the noted Defender of the Faith, Henry VIII, was of a different mind. HO enticed a number of Irish nobles to visit his court, seized them and had them thrown in the Tower. When the sons of the nobles took to the field against the treacherous Tudor Kingi he had a surprise in store for them, a weapon of ultimate horror called the cannon. The rebellion was crushed and the instigators hanged. That was Henry VIII when he was a moderately compassionate man — before the Reformation.

The Effects of The Reformation in Ireland

That movement of reform, carried out principally by Henry VIII and his daughter Elizabeth 1, added a new dimension to the trials and tribulations of the Irish people under English rule. The Irish heretofore had only been an enemy on the battlefield, now they became even more of a threat to the throne — they were living examples of Papist thought, word and action. In other words, they were anathema to the new Church of England.

The Act of Uniformity, which Elizabeth I ran through an obedient Parliament in 1560, decreed that only one liturgy was acceptable, that of the Church of England. The penalty for any overt objection to the new religious scheme was death, with the manner of execution varying according to the sentencer’s particular creativity of mind. Most were not creative and the hanging tree became the symbol of Irish doom.

The number of unspeakable atrocities committed in the name of the Virgin Queen will never be known, but they were carried out daily on a people whose only crime was that they despised foreign rulers and their attempts to force on them a religion they found wanting and odious. The Irish cherished freedom and the right to worship as they pleased, namely the now thousand-year-old tradition of the Roman Catholic Church.

The seizures of men and property under Henry VIII and Elizabeth I impoverished the people and Church in Ireland, but could not extinguish the spirit of either. The faith of the people remained intact and the Church was primarily responsible. In caves and on hillsides, by privet hedges and along the byways of Ireland, mendicant friars and priests by the hundreds preached the faith oftheir fathers in their fathers’ tongue. Wherever they went throughout the length and breadth of Ireland, these men of God found a people more than eager to hear their words and to honor them.

The Church was primarily responsible. In caves and on hillsides, by privet hedges and along the byways of Ireland, mendicant friars and priests by the hundreds preached the faith of their fathers in their fathers’ tongue. Wherever they went throughout the length and breadth of Ireland, these men of God found a people more than eager to hear their words and to honor them.

Though the English tried mightily to snuff out what they considered the last flickerings of Roman Catholicism, their efforts only served to kindle the embers of faith into a raging flame. No sooner would one priest reach the end of his earthly journey at a hanging tree, than another would appear as if by magic. As often as not, the new priest was a lad who only a few years earlier had received his catechetical instructions through a privet hedge and then slipped off to the continent to study for his holy orders.

There were other reasons to slaughter the Irish, to be sure. Appropriating their land was one of the principal ones, but any excuse would do in a pinch. When the habitants of Munster, for instance, proved an irritant to their English landlords, the Crown, in the form of Sir William Pelham, wreaked havoc upon them. He later boasted to Elizabeth I “that the local citizenry had been reduced to the point where they now prefer death by the sword to starvation.”

Oliver Cromwell

As proficient as Good Queen Bess’ minions were at devastating the natives, their efforts paled in comparison to those of a commoner who came along a century later — Oliver Cromwell, a name that will live in infamy as long as one Irishman draws breath anywhere on the face of the earth. While he was certainly not the first man of power to attempt the extermination of a race, hit try at genocide ranks with the very best. It was, for instance, much more noteworthy than that of Walter Devereaux, Earl of Essex, who sought to please Elizabeth I by destroying thousands of Irishmen.

Of course, there are those who insist the Irish brought it on themselves by their repeated refusals to accept the lot accorded them by the English. Rebellion, armed and otherwise, was an ever-present reality in all corners of the Irish countryside. In 1649 Cromwell was placed in charge of a large army, one well-equipped and trained, and dispatched to Ireland to subdue, for all time, its obstinate people.

After landing at Dublin, Cromwell turned northward and fell upon the coastal city of Drogheda. He smashed its defenses and laid it waste. Then he got down to the grisly business at hand, the implementation of his plan of conquest — take one stronghold at a time and then kill every man, woman and child who survived the onslaught. With 8,000 foot soldiers, 4,000 horse soldiers and the latest weaponry at his disposal, his goal seemed achievable.

Alas, even Cromwell tired of the slaughter. It wasn’t that he had objections to it, it was just that it was so time-consuming that it reduced his overall efficiency. He came to realize that at his present rate of conquest and extermination, he would reach old age before completing the task at hand. He devised a method of speeding things up that, while more subtle, was nevertheless as brutal. It has been known for centuries in the civilized world as slavery.

He divined that Irish women, girls and even young boys could be gotten rid of quickly and profitably by packing them on ships headed for the Crown’s colonies in the West Indies, where the planters and soldiers were already tiring of a steady diet of dark-skinned women. In all, over 30,000 women and children of Ireland were dispatched to Jamaita and other Caribbean ports of call, while an additional 4,000 were sent to the ripening colony in Virginia.

As for the men, their fate was little better. Nearly an equal number of them, especially those from the routed armies of the mightier Irish chieftains, brought a fetching price from the continent, where royalty knew the value of good fighting men. The armies of Poland, Spain and France were soon set rattlina by the presence of tall, fair-skinned Irishmen, whose valor was assured.

But when even these methods could not rid Ireland of the Irish, Cromwell was driven to rage and finally despair. It was at this time that he issued his famous cry, “Go to hell or Connaught.” Thus, the remaining Irish were to be herded on a reservation and kept there at all costs, the better to prevent them from havina any influence on the new settlers the Crown was bringing over daily from Scotland and other sections of Britain.

It was no garden spot that Cromwell picked for the Irish to spend their future existence. Connaught, a desolate, wind-swept corner of northwestern Ireland, was described by one historian of the time as “a province with not enough wood to hand a man, water enough to drown him or earth enough to bury him.” As Nelson Callahan suggests in his accompanying piece, a case might be made for hell.

Some of the more stubborn Irish refused to be transplanted and took to the woods and mountains in other provinces, living lives that have been described as “of wild brigandage.” Whatever price the Crown put on their heads, they survived, attended to spiritually by their privet hedge guidance counselors and, no doubt, by a host of magical fairies, the very same wee people who were wont to play tricks on those bent on harming the Irish. They did a terrible thing to Cromwell’s soldiers in Connaught, for instance. Within 40 years of their arrival in that province, not one of their children could speak a word of English.

Cromwell was by no means the last of Ireland’s tormentors. There were so many who followed him that it would take a tome just to list their names. What must be remembered is that from the time of Henry VIII to Victoria Regina, the tormenting centered on the Irishman’s religious beliefs and practices — his Roman Catholicism.

The Force of Religion

When Nelson Callahan points out the fact that the Irish were “culturally Catholic,” he is not only stating the case correctly, but with kindness. The true Irish from Patrick’s day on have been steadfast Catholics to the very marrow of their bones and no other race has so willingly paid such a fearsome price to retain its religion.

The Irishman’s fidelity to his faith was and remains astounding. He has clung to his Catholic ways with a tenacity unmatched in the past. It was, in fact, this very clinging to the faith of their fathers that enabled the Irish of the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th Centuries to overcome the persecutions, the poverty and pestilence visited upon them by their enemies, be they of barbaric or of royal bloodlines. They refused to be either annihilated or converted. The deep religious convictions of the Irish people gave them invincible strength. They were deprived of their leaders, their churches, their schools, their lands, their houses and their language, yet as a nation they swung forward, bound together in a triumphal march unprecedented in history.

So that one might better understand this triumphal march, it should be noted that in 1672, after Cromwell had wreaked his evil will upon the Irish, they numbered but a million souls. A century and a half later, when the Irish were to disperse themselves worldwide, the nation numbered seven million, having overcome wholesale slaughter, starvation, not to mention dispossessment of their very homes. As an anonymous Irish historian wrote over 200 years ago: “The fools, the damned fools. They thought that by conquering our land they could as easily conquer our spirit. The fools, the damned fools.”

The Complex Gaelic Language

The language known as Gaelic, which the People of Ireland themselves refer to as “Irish,” is an ancient tongue, one of the Indo-European group to which English also belongs. It is not, however, an easy language for English-speaking persons to master. Its grammar is complex. Gaelic nouns, for example, are like Latin ones in that they change their ending according to their use in the sentence. Because the language has dropped many syllables since it was given a written alphabet in the Eighth Century, and because multiple-letter combinations can make a single sound, many modern words contain letters which are not pronounced. This volume makes no attempts to utilize accent marks used in the Gaelic alphabets. Below are some common Gaelic words, and some words used in this book, with their phonetic equivalents:

Erie (Ireland): “Airuh”

Erinn go bragh (Ireland forever): “Airin go braw”

Dail Eireann (Parliament of Ireland): “Dawyl Airun”

Sinn Fein (Warriors of Destiny): “Shin Fane”

Aghaidh (face): “Eye”

Fleadh cheiol (music festival): “Flahkyoil”

Insert by the courtesy of Time-Life Books, Inc.