Main Body

4. Romanians in the United States

The Civil War

It is uncertain how many Romanians came to the United States before the 1890’s, but historical records show that during the Civil War five Union Army officers were of Romanian origin.

Captain Nicholas Dunca was born in Jassy, in the Romanian province of Moldova. He had taken part in the 1848 revolution in Italy, and a few years later, he emigrated to the United States. When the Civil War broke out, Dunca enlisted in the 8th Regiment of Volunteers of New York State.

His devotion to military discipline was much appreciated by his superiors; so much so that before the battles of Centerville on July 18, 1861, and Bull Run, July 21, 1861, he was appointed to the rank of captain.

In 1862 Duncas’ regiment distinguished itself in the Battle of Cross Keys, Virginia, and Captain Dunca fell mortally wounded. He is buried in the churchyard of Union Church at Cross Keys.

The story of General George Pomutz is more elaborate. Pomutz was born in 1828 in the town of Gyula, Hungary, a few miles west of the present Romanian-Hungarian border. He was Romanian by birth and Eastern Orthodox by religion.

His well-to-do parents sent him for higher education to Vienna, Austria and St. Etienne, France. In Vienna he fell in love with the daughter of a noble family, but the girl’s parents opposed their marriage. The couple fled to Hungary and Pomutz joined the army of Louis Kossuth who led the Hungarian revolt against Austria in 1848.

Together with other officers of the defeated Kossuth army, Pomutz and his wife came to the United States in 1849. In this same year, the name of Pomutz appeared on the rolls of the Pythagoras Lodge of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Free Masons of New York.

When the Pomutz couple’s money began to run out, they joined a group of Kossuth exiles in New Buda, Iowa. Pomutz’ wife abandoned him in 1860.

Heartbroken at his wife’s action, Pomutz sought forgetfulness in the Civil War. On October 10, 1861, he joined Colonel Reid in organizing the 15th Regiment of Iowa Volunteers and soon received the rank of captain.

His early European military education now became helpful to the Union Army. General William Bellknap, later Secretary of Defense, praised Pomutz for his military ability. Pomutz distinguished himself in the battles of Shiloh, Corinth, Vicksburg, Atlanta and Savannah. Although severely wounded at Savannah, he eventually recovered.

At the end of the Civil War, on February 16, 1866, President Andrew Jackson named Pomutz consul general of the United States in Russia’s capital, St. Petersburg, where he remained until he died. Before his death Pomutz was promoted to the rank of brigadier general by President Rutherford B. Hayes.

Three other Romanians served in the Union Army during the Civil War, but their stories are less known than those of General Pomutz and Captain Dunca.

Emanoil Boteanu, born in 1836 in Moldova, in his youth became an officer in the army of Al. I. Cuza who sent him to the United States when the Civil War broke out. Boteanu’s mission was to observe the war and to report his observations to Cuza.

Arriving in Washington, Boteanu presented himself to Secretary of State William Seward, who placed him in the Army of the Potomac in February 1865. Boteanu took part in the Battle of Richmond on April 2, 1865 and was present at the surrender of General Lee on April 9, 1865 at Appomattox.

His reports from America were published in the Romanian Army’s official publication during 1865. Boteanu returned to Romania and took part in the War for Romanian Independence as commander of the sixth Dorobanti Regiment in 1877-1878.

Another Romanian who fought in the Union Army was Eugen Alcaz, a native of Moldova. The ruler of this principality sent young Alcaz to France where he graduated from the military school of Metz.

He crossed the Atlantic Ocean in a sailboat, volunteered for the Union Army and was wounded in the Battle of Bull Run. Returning to Romania, Alcaz was named colonel in the Army of Cuza.

On returning to civilian life Alcaz was among the founders of textile mills in Neamt and Bohusi. He died in 1892 in Moldova.

Eugen Ghika was born in Romania in 1840 to Nicolae and Ecaterina Plagino. When he heard of Lincoln’s appeal for volunteers, Ghika came to New York and volunteered to serve in the Fifth New York State Regiment.

He was wounded in his first battle. After he recovered Ghika was promoted to the rank of captain. While in the hospital recovering from his wounds, Ghika reported to the “Buciumul” newspaper in Bucharest the death of Captain Nicolae Dunca, among the first Romanians who volunteered for the Union Army.

At the end of the Civil War Ghika returned to Moldova where he was elected member of the Senate. By marrying Jeanne Katherine Kesco, Ghika became a brother-in-law to Milan Obrenovic, King of Serbia. In his old age Ghika retired to his estate at Asau-Comanesti where he died on December 20, 1914.

The Major Immigration Period

The majority (75 percent) of Romanians who came to the United States were from Transylvania. The second largest group came from Bucovina and only a very small percentage, not more than eight percent, came from the “Old Romanian Kingdom” composed of Muntenia and Moldova.

When the Romanians started their immigration to this country en masse, during the period between 1900 and 1914, Transylvania was ruled by Hungary and Bucovina was part of Austria. In other words, only those Romanians left their homes to come to this country who were subjects of either Hungary or Austria.

In both the cases of Transylvania and Bucovina, the great majority of the Romanian immigrants were peasants, coming from rural communities and unskilled in industrial work.

Although the lot of the Romanian peasant in the “Old Romanian Kingdom” was not among the best in the world; he preferred to stay at home. At least his rulers were Romanians.

Besides the unfriendly and hostile attitude of the Magyar government toward the Romanians under their rule, another factor was responsible for large-scale Romanian emigration from Transylvania. In Transylvania many villages and regions are shared by both Romanians and Saxons. The latter were colonized there 800 years ago. The German speaking Saxons of Transylvania had easy access to newspapers from Germany and the story of fabulous America soon became familiar in Saxon villages.

Newspapers from Germany which reached the various Saxon villages and towns of Transylvania were full of advertisements for cheap travel to America from the ports of Hamburg and Bremen. Austrian papers, printed in German, praised the advantages of sailing to America from Fiume, at that time ruled by Austria.

The name of “Missler” soon became a household name among those who were dreaming and planning to go to America. It was the Missler travel and labor agency in Germany which worked the hardest to bring cheap labor to fabulous America.

The Missler organization had large hotel-barracks in Hamburg where would-be immigrants to America could stay until places were found on some ship going to New York, Boston or Philadelphia, with New York occupying first place in the minds of the Romanians.

The cost of steerage passage was around $30 to $40. As many as 50-80 persons slept in the large steerage halls. Food was served in military style with the passengers lining up, dish in hand, slowly marching to the large kettles from which ship attendants would dispense simple food.

Even at its best, steerage accommodation was far from being comfortable ahd the ocean trip lasted from three to four weeks, depending on the size of the vessel.

On arriving in the Port of New York, all immigrants spent some time at Ellis Island where immigration inspectors examined the newcomers.

Both Transylvanian Romanians and Saxons came to America in the hope of saving enough money to pay debts incurred in the Old Country and, upon returning to Transylvania, to buy land and build a new house.

America was also a magnet for all who resented the debasing economic and political treatment meted out by landlords and Hungarian officials in Transylvania and by the Austrians in Bucovina. Also, hundreds of young men fled their homes in Austria-Hungary to avoid long years of service in the Austrian emperor’s armies.

The common aim among Romanian immigrants was to work hard and save “one thousand dollars and the cost of the passage” (Mia si Drumul). It was the hope of most Romanian immigrants that with the money they could assure themselves a comfortable life in Transylvania. That is the reason why so many failed to make long range plans to stay in America.

Nearly all Romanian immigrants came here from the countryside of Transylvania and Bucovina. Their sudden transition from farm laborers to industrial workers was a great physical and emotional shock for most of them.

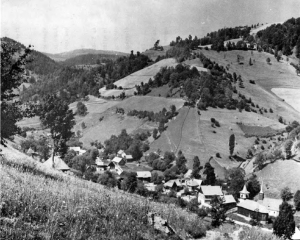

Lack of English and nostalgia for their home villages and families contributed greatly to making the new Romanian immigrants feel isolated and ignored in America. Early immigrant literature printed in almanacs and newspapers reflected almost exclusively the nostalgia of the Romanian immigrants for the green valleys and modest villages in the Old Country.

The boarding house keepers and saloon proprietors played an important and interesting role in the settling of the Romanian immigrants in different cities. Except for those who came to a relative who emigrated earlier, most of the Romanians came to the address of some Romanian boarding house or saloon. If the immigrant came here through a labor agent working for some factory or mine, the newcomer would be greeted at the railway station and then taken to the agent’s favorite Romanian saloon.

The arrival of new immigrants among the people who settled here earlier, was always a solemn occasion. Once the newcomer’s meager belongings were placed in a secure place, and sleeping accommodations were found, the “Old timers” would gather around the new arrival and bombard him with questions about the Old Country. How is life there now? Who died in the village and who is getting ready to emigrate to America?

How fate, a casual address and some friend’s letters were responsible for selecting a place in the new world is illustrated by the Romanian settlement in Ilasco, Missouri.

None of the Romanians who went to Ilasco had any idea where the place was in America. It was enough that it was in the United States.

It seems that a Transylvania Saxon from the town of Vintz came to the United States in 1900 and after some wandering around the country finally settled in Ilasco, Missouri where he worked in the cement mines of Portland Cement Company.

In due time he began sending letters to his relatives and friends in central Transylvania, bragging about the “riches” one can earn in fabulous America. He reported that for 12 hours’ work he earned the sum of $1.50 per day. To the relatives in Transylvania this meant seven Crowns, one dollar having the value of five Crowns.

At that time, in 1900, seven Crowns were the wages for a whole week’s work in Transylvania. Just imagine, one can earn as much money for one day’s work in America as one did in six days in Vintz.

It did not take long for a few adventurous Romanians to copy the Saxon’s address in Ilasco, borrow $30 for the ocean passage and leave for America.

Since they knew no one in America except the man in Ilasco, they went there directly from New York. The train ride took the last of their money.

In a year or two the Ilasco, Missouri Romanian colony was big enough that a fraternal lodge could be formed. Old timers remember a black man in Ilasco who spent so much time among Romanians that he learned Romanian. It was this black man who often read the letters from the Old Country to the Romanian immigrants who did not know how to read.

Although in the Old Country nearly all Romanian immigrants were peasant farmers, on arriving in America they found that it was more practical to work in mines and industrial plants. Consequently they gravitated to the industrial centers of the country, mostly on the eastern seaboard of the United States. Ninety percent of the Romanian immigrants sought homes in the cities, near their places of work, in the vicinity of industrial plants.

It was indeed remarkable how the Romanian immigrants of peasant stock, dedicated for generations to agriculture, adapted themselves to industrial life in America. Only a small number are still farming and sheep herding in Montana, Wyoming and in North and South Dakota today.

Among the industrial states, Ohio, Pennsylvania; Michigan and Indiana have the largest number of Romanian communities. In order of their numerical importance, following are the states and communities in which Romanians settled and worked:

OHIO: Cleveland, Youngstown, Canton, Akron, Alliance, Cincinnati, Lorain, Warren, Massillon, Campbell, Salem, Niles, Toledo, Lisbon, Struthers, Martins Ferry, Zanesville, Bridgeport, Girard, Hubbard, Cambridge, Yorkville and Barberton.

PENNSYLVANIA: Philadelphia, Homestead, McKeesport, Pittsburgh, Sharon, Farrell, New Castle, Erie, Woodlawn, Elwood City, Universal, Altoona, New Salem, Union, Scranton, Harrisburg, Zelienople, Windber.

MICHIGAN: Detroit, Highland Park, Flint, Lansing, Grand Rapids, Kalamazoo and Pontiac.

ILLINOIS: Chicago, South Chicago, Aurora and West Pullman.

INDIANA: Indianapolis, East Chicago, Gary, Hammond, Terre Haute, Fort Wayne, Clinton, Kokomo, Indiana Harbor.

NEW JERSEY: Trenton, Roebling, Florence, Perth Amboy, Camden, Newark, Jersey City, Hoboken, Elizabeth, Passaic, Patterson, Mount Holy and Woodbury.

MASSACHUSETTS: Boston, Southbridge, Worcester, Webster and Blackstone.

CONNECTICUT: Bridgeport, North Grosvenor, Dale and Torrington.

CALIFORNIA: San Francisco, Los Angeles, Sacramento, Pittsburgh, Riverside and Florin.

MINNESOTA: St. Paul, South St. Paul, Minneapolis, North Hibbing and Duluth.

WISCONSIN: Milwaukee, Madison and Racine.

WEST VIRGINIA: Wheeling, Weirton, Thorpe, Follansbee and Whitman.

NEBRASKA: Omaha, South Omaha and Hastings.

MARYLAND: Baltimore and Hagerstown.

RHODE ISLAND: Woonsocket.

COLORADO: Denver and Pueblo.

WASHINGTON: Seattle, Tacoma and Spokane.

MONTANA: Helena and Butte.

OREGON: Portland.

IOWA: Clinton, Bettendorf and Sioux City.

NEW YORK: New York City, Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, Buffalo, Tonawanda, North Tonawanda, Rochester, Watertown, Middletown, Niagara Falls, Elmira and Canton.

The cities and towns listed have had and still do have Romanians in reasonably large numbers. There are cities like Miami, Florida where Romanians have moved only recently, after their retirement from active work. Individual Romanians can be found in almost every part of the country. Some live totally isolated from the rest of the Romanians.

Relative latecomers to this country, the Romanians’ economic development was slower than that of immigrant groups who entered America before 1890. For years the saloonkeeper was the most prosperous man in any Romanian community. He was followed by the grocer. It can be stated with reasonable accuracy that until about 1915 the boardinghouse keepers, saloon owners and the grocers were the most respected laymen in an average Romanian community.

No exact figures can be given to represent the number of Romanians who emigrated to the United States. Statistical data furnished by the U.S. Census Bureau is not accurate on this point because most Romanians from Transylvania (the majority) were recorded as coming from Hungary, and those from Bucovina were legally citizens of Austria.

When they entered the country, they were listed as either Hungarians or Austrians. Judging from membership in Romanian fraternal societies, churches and other reliable data, it is conservatively estimated that about 120,000 Romanians emigrated to the United States from 1895 to 1914.

World War I and Afterwards

The start of World War I in 1914 stopped the Romanians from coming to America. From the start of the war in 1914 until the end in 1918, because the Romanians were, legally, citizens of Hungary and Austria, they were without any communication with their homes and families in the Old Country.

The higher wages paid during World War I and the inability to send money to the Old Country helped Romanian immigrants save money. Thousands planned to take their accumulated savings to the Old Country at the end of the war. The money was to be spent on buying land, building a new house or opening some sort of store. In other words, the returning immigrant was ready to spend the rest of his days in the Old Country as a landowner or storekeeper.

Besides wishing to enjoy the highly valued American dollars in their Old Country home towns, the Romanian immigrants were prompted to return by the historic new fact, that the Peace Treaties of 1919 made possible the union of Transylvania, Bucovina and other Romanian lands; until now under foreign rule, with the Old Romanian kingdom.

The union of all the Romanian lands into one political unit was a dream nurtured by the Romanians for centuries. Romanians in America collected much money to help the creation of Greater Romania, and when the dream became a reality, thousands left America to become landlords in Romania.

The rush for Romanian passports needed to return to the Old Country was considerable, and the small Romanian Legation in Washington was hard pressed to keep up with the demand.

Legally, the Romanians applying for passports were Hungarian or Austrian citizens when they left the Old Country some years previously. Changes in European boundary lines and the formation of Greater Romania made the same people Romanian citizens.

The figures given below for the number of passports issued to returning Romanians do not tell the whole story because some Romanians had acquired U.S. citizenship and were traveling to Romania on American passports.

From August 1 to December 31, 1919 the Romanian Legation in Washington issued 2,560 passports to Romanians returning to the Old Country.

In 1920 the number of such passports grew to 7,136. By 1921 the number decreased to 2,568. In 1922 only 1,205 passports were issued to returning Romanians and in 1923 the figure fell to 691.

The above figures clearly indicate that as time passed and Romanians in America became better informed about living possibilities in Romania, fewer Romanians returned to their birthplaces. The Romanian standard of life simply could not compete with the American.

The return of so many Romanians to Romania had an interesting effect on the lives of children born in some Romanian families. In many cases parents who decided to return to the United States left their children to be cared for and educated in Romania. Usually the grandparents assumed responsibility for the youngsters.

Some of the children remained in Romania until they graduated from high school. Upon their arrival in America many such American-born Romanian young people had to work hard to lose their Romanian accent.

Hundreds of American-born children of Romanian parents who returned to the Old Country grew up in Romania, and when war clouds appeared on the horizon in the late 1930’s were unable to return to the United States.

For a few years after the end of World War II, the communist government of Romania refused to permit these American-born people to leave Romania, but in recent years, the situation has greatly improved. Today any person born in America but living in Romania can return to the United States without too much trouble.

To the Romanians living in the United States; the situation in their homeland established by the Peace Treaties of 1919 was especially significant: they had a taste of real freedom in this country and they were anxious to enjoy freedom in a United Romania, too.

It bears repeating that the Romanians in Transylvania had endured the oppressive rule of the Hungarians and Austrians for centuries. Leaders of peasant uprisings against Austria and Hungary were cruelly executed by the oppressors and became heroes to the Romanians of Transylvania and Bucovina.

In free America, the Romanian immigrants gave their lodges the names of the Old Country folk heroes, Avram, Iancu, Horia, Closca and Crisan, to show their dislike for the foreign rulers.

In Romania, the desire of thousands of American Romanians to enjoy the newly established freedom of Transylvania and Bucovina was cleverly exploited by a number of banks. They sent emissaries to the United States, who visited most of the more important Romanian settlements, soliciting deposits for their banks in Romania. Advertisements published in the various Romanian papers in the United States urged Romanians to send their savings to the Old Country. The 1925 Almanac, published by the “America” Romanian daily in Cleveland carried the advertisements of 15 banks from Romania, all soliciting savings deposits from America

With each succeeding year, however, the number of such advertisements dropped due to the gradual devaluation of Romanian currency and the collapse of many banks in Transylvania.

Another sensitive problem affecting Romanians in this country who were legally subjects of Austria and Hungary was the action of fledgling Romanian organizations in using the Romanian colors on their flags.

Most Romanian immigrants still had their families and relatives in Transylvania and Bucovina Hungary and Austria, and they could have suffered more than unpleasantness for the action of their kin in America.

Using the Romanian colors of red, yellow and blue in Transylvania and Bucovina was a crime. In America, however, Romanian immigrants were quick to use the forbidden colors on their flags.

The first Romanian organization to defy the Austrian and Hungarian law was the Romanian Club of Cleveland. The greatest pride of this small group was that it was the first Romanian organization in America to use the Romanian colors in 1903.

To make sure that friends and relatives in Transylvania took notice of this brave act, a group photograph of the members gives not only their names but also their home villages. They were: John Morar, Costica Tahopol, Dumitru M. Barza of Saliste; Simion Baraza and his wife from Sebes; Nichifor Barza of Ghertan; Nicolae Mihaltian and wife from Sebes; Dan Borzea of Ghertan; Marcu Lazar, George Opincar, Ilie Martin of Saliste; Vasile Dobrin, Ilie Apolzan of Sebes and Peter Vitalar (birthplace unknown).