Main Body

6. Romanian-American Organizations and Institutions

Fraternal Lodges

When the Romanian immigrant left his village for a new life in America, he was a peasant, a farmer as were his ancestors for centuries.

When he arrived in the United States, he was suddenly thrown into the turmoil of a hectic industrial world. There were no preliminaries to prepare him for this sudden change.

In the 1900’s industrial safety was still in its infancy in rapidly developing United States. When large masses of unskilled immigrants flooded the mines and steel plants, accidents were frequent.

Father Aureliu Hatiegan, among the first Romanian priests to arrive in this country from Transylvania, was pastor of St. Helena Romanian Catholic Church of Byzantine Rite in Cleveland when he wrote these lines to his fellow Romanians in 1907:

In America many of our Romanian brethren leave their homes in the morning full of life and hope and in an hour or two are taken to a hospital crushed to death or with the loss of a limb. Sometimes this is the fault of the victim but many times the fault lies with the bosses who have little respect for the fate and safety of the immigrant.

When a Romanian worker died, very often his fellow Romanians had to “pass the hat” to collect the cost of a modest funeral.

It soon became apparent to immigrants that some sort of organization was needed to protect workers against accidents and other tragedies. Thus, the idea of the fraternal lodge was born.

The remarkable thing about the Romanian lodges and churches in the United States was that their founders were peasants and workers, at that time fresh from the villages of Transylvania and Bucovina. What they lacked in formal education was compensated for by their determination to succeed at all costs.

Although few of the early Romanian immigrants spoke English or had any experience in conducting organizations, they had the important assets of common sense and the willingness to experiment.

In today’s affluent society, with its high hourly wages, it is hard to imagine the hardships of Romanian immigrants in the early 1900’s when wages in factories and mines hovered around $1.50 per day for 12 hours’ work.

Yet, from these miserable wages, the first Romanian immigrants were able not only to take care of their daily necessities and save a little but also to establish fraternal societies and churches.

It is hard to imagine that the first monthly dues at an average Romanian fraternal lodge amounted to 15 cents per month. From these modest fees, a death benefit of $80 was paid to the surviving family.

The first Romanian organization in the United States was the “Carpatina Club” of Cleveland, formed on November 2, 1902 under the chairmanship of Pavel Borzea.

By coincidence, a similar group was established on the same day in Homestead, Pennsylvania, under the name of “Vulturul” (The Eagle) under leadership of Ilie Martin.

Both the Carpatina and the Vulturul societies still existed in 1975. Martin, the man in Homestead, instigated the movement to establish a central organization for the various Romanian societies in this country. Such a central organization was founded at a meeting in Homestead on July 4, 1906, adopting the name, Union of Romanian Societies of America.

From the modest start of 14 branches in 1906, the Union grew to a membership of 15,000 in 1925 with about 60 branches in various states. Due to the return of many members to Romania and the deaths of the older Romanians, this membership became smaller year after year. In 1975, the Union’s membership was 5,000 in 44 branches.

The progress of the Union of Romanian Societies of America was not made without difficulty. Unfortunately, religious issues helped to start many misunderstandings among the Romanians.

It should be noted here that the majority of Romanians belong to the Eastern Orthodox faith. A considerably smaller number are Catholics of Byzantine Rite, known as “uniates.”

The first Romanian priest to arrive in Cleveland was Dr. Epamimonda Lucaciu, a famous name in Transylvania. He reached Cleveland in the fall of 1905. Besides organizing St. Helena Parish, he started publishing a Romanian language weekly, the “Romanul” (the Romanian).

In 1906 the first Romanian Orthodox priest arrived in Cleveland. He was Father Moise Balea, who later became known as the founder of most Romanian Orthodox parishes in this country.

Like Father Lucaciu, Father Balea also edited and published a weekly, “America.” These two newspapers, “Romanul” and “America,” voiced the major religious differences between a Uniate Catholic and an Orthodox priest. Bitter feelings were aired, and when “America” was sold by Father Balea to the fledgling Union of Romanian Societies of America, the controversy continued in lodges and societies.

In a short time two major factions developed. The one around the weekly “Romanul” was led by a small group of priests and intellectuals. The other was supported by tavern keepers and factory workers. The few Orthodox priests forgot their religious differences and joined the Uniate priests.

It should be noted here that the Romanian immigrants who came to America from Transylvania and Bucovina nurtured bitter memories of the so-called “intellectuals” in the Old Country. The “gentlemen” in the Austrian and Hungarian-ruled provinces usually were Hungarians and Austrians, that is, enemies of the Romanian peasants.

This aversion for the “city slickers” was brought to America, too, with the result that Romanian workers felt uneasy in the company of “gentlemen-intellectuals.”

In the factional fight between the intellectuals and the workers, the group around the weekly “Romanul” accused the leaders of the new Union of Romanian Societies of America as being incapable of leading a central organization.

On the other side, leaders of the Union of Romanian societies counterattacked by claiming that the intelligentsia among the Romanians in America represented nobody. They hinted that members of the small intelligentsia group were too friendly with the Austro-Hungarian consulate. Spokesmen for the Union time and again repeated that the leadership should go to the representatives of the workers and not to the intellectuals.

This controversy continued with great bitterness even up to 1912. At a special meeting of the Union held in Cleveland on December 19 of that year, the delegates of the various lodges held their discussions amid loud disturbances.

The presiding officer, George Grama, finally told the delegates: “Those siding with the priests, please sit with them. Those siding with the workers, sit with us.” Three delegates joined the priests, the rest joined the workingmen’s faction.

The result of this factional fight was the adoption of Paragraph 4 of the Union’s bylaws which states: “Priests, clergymen and other intellectuals shall have no right to be elected officers of individual lodges or of the central Union.”

The introduction of Paragraph 4 into the bylaws of the Union of Romanian Societies of America had a fateful effect on the relations between Romanian workers and the Romanian intellectuals. The cleavage was never repaired. The intransigent attitude of the two factions went so far that on the evening of the day when Paragraph 4 was adopted in the bylaws of the Union, friends of the priests attacked the building of “America,” damaging walls and breaking windows.

In spite of these conflicts, the Union of Romanian Societies enjoyed progress and growth, so much so that in 1917 the central organization had 13,000 members in the country.

Presidents of the Union of Romanian Societies, who directed the central organization from 1906 on, in order of their term in office are: Ilie Martin of Homestead, Nicolae Barbul, Dumitru Spornic, Ioan O. Popaiov, Vasile Lapadat, Aldea Candea, Vasile Vladutiu, George Grama, Ioan G. Hoza, Ioan Pacurar, Ioan N. Serb, Nicolae Dragos, George Fulea, Pantilimon Chima and Paul D. Tomy.

Opponents of the Union of Romanian Societies succeeded in organizing 12 lodges which were centralized in the League of Romanian Societies of America, with headquarters in Youngstown.

In 1927 the Union of Romanian Societies of America and the League effected a merger and since then the central body had been called the Union and League of Romanian Societies of America. With headquarters in Cleveland, it has a national membership of 5,000.

Adam A. Prie of Alliance and Cleveland was the first president of the newly merged Union and League. At his election the delegates to the convention apparently overlooked the meaning of the famous Paragraph 4 of the bylaws since Prie was the first president of the Union and League with a college education. He was a graduate of Mt. Union College in Alliance.

Prie was followed in the presidency by John L. Spornic, Nicolae Balindu, Joseph J. Craciun, S. S. Fekett, Peter G. Nicoara, John C. Coman, George Dobrea, Eugen Popescu and John Popescu.

The story of the Union and League of Romanian Societies of America is important because this central organization and its official organ, “America,” were the leading factors in all cultural and patriotic manifestations of Romanians in this country.

Since nearly all its members came from Transylvania and Bucovina, the Union and League worked feverishly to promote the idea of a united Great Romania. During World War I the Union and League and “America” organized the National League to work in the political arena for the formation of a United Romania. Much money was donated to the Romanian Red Cross, the Romanian Navy and to the cost of several monuments in Romania.

The influence of the Union and League extended into many and varied activities.

Members of the Union and League from the neighborhood of Youngstown formed the Romanian Volunteers in the U.S. Army to fight in France.

The Union and League lead a group of several hundred America-Romanians to the tenth anniversary celebration of the Union of All Romanian Lands, held in Bucharest in 1929. Delegates were received with pomp and ceremony by the Romanian royal family and the government in Bucharest.

Perhaps the greatest role of the Union and League in the lives of Romanians in America was its steadfast support of “America,” the official organ of the central group. Hundreds of Romanian workers, who came to this country with very little education, perfected their knowledge of reading and writing by faithfully reading “America.”

Other noteworthy Romanian organizations in the United States were the five Macedonian Romanian groups in New York, Woonsocket, Rhode Island, Bridgeport, Connecticut, Boston, Massachusetts and Manchester, New Hampshire. Members of these organizations started coming to America in 1900 from Albania, northern Greece and Serbia. The first group was the Farsarotul in New York, founded in 1903.

Jews from Romania formed their own lodges and religious organizations, mostly in New York. There has been little, if any, contact between Romanian Jewish groups and the Romanians of other persuasions.

Romanian socialists and communists had, until recently, small sized organizations in about 15 industrial cities of this country, the largest being in Detroit.

Religion and Parish Life

In the mind of a Romanian his religion and his nationality are closely interwoven.

In the Old Country most of the Romanians were ruled by foreigners who found all sorts of ways to harass their Romanian subjects. For a Romanian the place of refuge, spiritual comfort and consolation was the church.

Like his fellow Romanians in Europe, the Romanian immigrants in this country belonged to two principal Christian faiths. The majority were Eastern Orthodox and the minority were Catholics of the Byzantine Rite, known popularly as Uniates. The latter recognized the authority of the Pope of Rome. The Orthodox have their own Patriarchs.

In the Old Country, village life revolved around church holidays and events closely connected with religion: christenings, weddings and funerals. This close relationship with religion was brought to this country by all Romanian immigrants.

In the Old Country every village had its church and priest. On arriving in the United states the Romanian immigrant found no churches and no priests of his own.

Besides the shock of being forced to change overnight from farmer to industrial worker, the Romanian immigrant, like all newcomers, had to suffer an additional shock — to be without a church.

Some did go to churches belonging to other nationalities but the language was strange and the Romanian newcomer did not feel at home.

Even though many immigrants planned to return to their European homes “once they saved a thousand dollars and the fare” most felt they needed a church here.

The late Nicolae Mihaltian, one of the earliest Romanian settlers in Cleveland, recalled the days when the Romanian immigrants had to live without the benefit of churches and priests. His favorite story was about Easter in Cleveland in 1900.

According to Mihaltian, who died in 1940, Easter was celebrated in Cleveland in 1900 in an unusual way. The Romanians, 12 in number, had gathered early on Easter morning in a rooming house on Herman Avenue, Cleveland’s West Side, where the first Romanian immigrants settled.

Some of them milled on the sidewalk, some talked about the inspiring church services that surely must be taking place in their villages in Transylvania.

Others brooded in different corners of the rooms, saying “if we could only have some Easter Bread,” called in Romanian Pasti. On Easter morning all Romanians partake of this sacred bread.

But there was no Pasti for them in Cleveland. There was a Roman Catholic Church in the neighborhood, it is true, but these newcomers dared not enter there for they knew neither the form of worship nor how to ask in English for the traditional Pasti.

One of the 12 suggested to celebrate the Resurrection in the great outdoors. Going northward they crossed E. 65th Street to a field where the Hill Clutch Company now stands, went over the railroad tracks and stopped on the shore of Lake Erie.

They noticed wild grape vines that had just come into budding. The grapes were most welcome to the Romanians for they represented the element of wine in the Holy Communion and the buds symbolized resurrection.

They ate some of the buds, imagining they were eating Pasti, embraced and kissed each other with tears of mixed joy and sadness in their eyes. Then they said “Christos a Inviat” (Christ has Risen) to each other, as it is done in Romanian churches.

Thus was the first Romanian Easter celebrated in Cleveland. It can be easily imagined that similar scenes took place in other places settled by the early Romanians.

No description of early religious life among Orthodox Romanians in the United States can be adequate without relating the story of Father Moise Balea, the first Romanian Orthodox priest to arrive here. He left his mark on many communities, and his contributions are discussed in more detail in the following chapter.

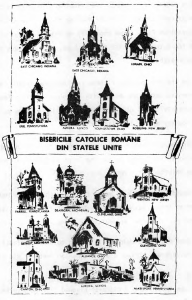

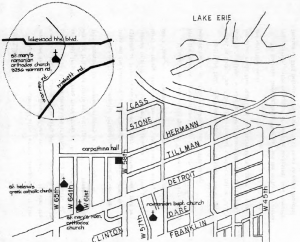

Ever since the Carpatina Club began functioning in 1902 and the first two Romanian churches, St. Mary Orthodox and St. Helena Catholic of Byzantine Rite, were established some 70 years ago, Cleveland has emerged as the center of Romanian life in the United States. The churches played a leading role in making Cleveland the major center.

Detroit, for instance, has a larger Romanian population than Cleveland, but Cleveland has retained its reputation as the Romanian center. As immigration goes, the Romanians arrived rather late compared to the older immigrant groups, like the Germans, Czechs, Italians, Poles and Slovaks. The Bohemian National Hall at 4949 Broadway was already five years old when the first appreciable Romanian group began its trek to Cleveland.

Besides the economic necessity of forming mutual aid lodges, the new Romanian immigrants also looked with some envy at the colorful parades and other celebrations staged by the older immigrant nationalities.

The earliest Romanians settled on the West Side along Detroit Avenue between West 45th and West 65th streets and Lake Erie. It was an area heavily populated by the Irish who were not particularly fond of their new neighbors, the Romanians.

The West-Side Romanians came from central Transylvania. Most of the Romanians who settled on the East Side, along Buckeye Road, were natives of the eastern counties of Transylvania.

Why did Romanians come to Cleveland? Cleveland had a reputation as a prosperous industrial city where employment was easy to find. A second, but nevertheless important, reason was that the West-Side Romanians were well acquainted with the Transylvanian Saxons who preceded the Romanians to Cleveland. It was easy for the Romanians to find old friends and fellow villagers among the West-Side Saxons.

In the 1900’s Cuyahoga County’s population of 439,000 found ready employment in the rapidly growing industrial plants.

Following in the footsteps of the Saxons, the West-Side Romanians began working in the plants north of Detroit Avenue along the lake shore. These plants included Hill Clutch Company, Walker Manufacturing Company, Westinghouse and the shipbuilding and ore docks.

Almost imperceptibly the West-Side Romanians began to displace the Irish from the Detroit-W. 65th area.

It was not long before the first Romanian churches were built in this neighborhood. These first parishes, St. Mary’s and St. Helena’s, were the first Romanian religious organizations in the United States.

There has always been a quiet rivalry between the faithful of St. Mary Orthodox Church and the parishioners of St. Helena Catholic Church of Byzantine Rite as to which was the first established in this country. Following are the historical facts concerning this rivalry and the reader can make his own choice.

About 50 Orthodox believers met at 164 Herman Street on August 28, 1904 and after many discussions decided to formally organize “St. Mary Orthodox Parish in Cleveland.” The first parish council and officers were also elected. Although the parish was formed, a church could not be erected and dedicated until the fall of 1907.

On the other hand, St. Helena Catholic Church of Byzantine Rite claims priority because it was the first to erect its church which was dedicated on September 16, 1906, a year before St. Mary Orthodox Church was erected. The parish of St. Helena was organized November 19, 1905.

St. Mary’s

The first officers of St. Mary Romanian Orthodox parish in Cleveland, elected on August 28, 1904, were confronted with enormous difficulties in transforming a dream into a reality. They were: Vasile Dobrin, president; George Puffu, vice president; Axente Gherman, secretary; Simion Herlea and John Lazar, treasurers.

Rev. Fr. Vasile Hategan, present pastor of St. Mary’s has published a story of the founding of St. Mary’s in the Golden Jubilee souvenir book of St. Mary’s, August 15, 1954. It reads in part:

The officers of the new parish sent a petition to the Archbishop of the Romanian Orthodox Church in Sibiu, Transylvania (then ruled by Hungary) in which they asked that the new parish be recognized and that a priest be sent to administer to the spiritual needs of the people.

Church authorities in Sibiu responded by sending a young priest, Father Moise Balea who arrived in Cleveland in November 1905, bringing with him the basic religious books for a new church. These books, like the Gospels, were signed by Elie Miron Cristea, who in time became the Patriarch of Greater Romania.

Father Balea’s arrival caused great joy among the Orthodox faithful. Services were held in various halls in the neighborhood, but soon the idea of having its own church building was promoted by the Romanian group.

Father Balea took the initiative of buying a lot at 6201 Detroit Avenue in the midst of the growing Romanian neighborhood. After ardent discussion among the members as to what kind of a church building should be erected, Father Balea proposed that a replica of the Orthodox Cathedral of Sibiu should be built in Cleveland at the cost of $25,000. The majority of the small parish then earned about $1.50 per day and they could not imagine spending $25,000 for a new church. The majority of the members expressed their opposition to the big church by saying that most of the Romanians would return to Transylvania. These people asked, “For whom shall we build a big church since we shall return in a few years to Romania?” The anti-big-church group won and a small edifice was erected at the cost of $7,500.

The opponents of a big church building were helped in their arguments by the severe economic depression which characterized the year of 1907. The newly arrived Romanians were frightened of the future and did not want to get into a debt which they felt they could not pay. Dedicated in the fall of 1907, the smaller church building served the parish until August 21, 1960 when a new church was built at 3256 Warren Road.

After the first building was dedicated at 6201 Detroit Avenue, Father Balea, a disappointed man because he lost his big-church-building plan, resigned and left the parish.

He transferred his attention and energies to other localities populated by Romanian immigrants, and, under his guidance and at his urging, about 20 Romanian Orthodox parishes were formed in various parts of the United States.

At the parishioners’ request, another priest was sent to America by the Orthodox church authorities in Transylvania. He was Father John Podea. Under his pastorate the newly built church, which during the 1907 depression was lost to the mortgage holding bank for nonpayment of interest, was repurchased from the bank.

When Father Podea resigned his pastorate in 1911, a new priest came from Transylvania, Father Ilarie Serb. In a short time more Romanian Orthodox priests arrived but this influx of priests was stopped by the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

On September 1, 1906, Father Balea founded “America,” the Romanian language weekly in Cleveland which later became a daily. On the masthead of the new weekly Father Balea placed the following note: “Published when I have time, disposition and money.”

He sold “America” on July 4, 1908 to the Union of Romanian Societies of America and ever since this publication has remained the official organ of the organization.

From Cleveland Father Balea went to pastorates in other cities until he finally settled in Detroit in 1935. He died suddenly on December 23, 1942 at the center of the Romanian Orthodox Episcopate in Jackson, Michigan.

When the outbreak of World War 1 in 1914 stopped the influx of priests from Transylvania and Bucovina, Romanian parishes in America were forced to accept church cantors who were ordained by Russian Orthodox bishops.

Until 1918 all Romanian Orthodox parishes led an independent parochial existence. It soon became evident that the establishment of a higher church authority would be necessary. Bishop Policarp Morusca came to this country from Romania in 1935 and from then on a stricter control was introduced in all Orthodox parishes.

The war years of 1916-1919 brought considerable prosperity to the Romanian workers’ group. Earning higher wages, they were able to donate more to their church. On May 4, 1918 the entire debt of St. Mary’s was paid up and the parish proudly announced that it had $1,226 cash in its treasury. Through the generosity of its more affluent members, the church also acquired two large bells.

In March 1915 St. Mary’s parish sent three delegates to a church congress in Youngstown. At this conclave the Romanian Orthodox parishes in the United States decided to leave the jurisdiction of the church authorities of Transylvania and become canonically connected with the Patriarchate of Bucharest.

It should be kept in mind that in the fall of 1918 the people of Transylvania voted unanimously to become part of the Old Romanian Kingdom, thus creating a Great Romania.

The prosperity of the War years induced many Romanian immigrants to invest savings in homes and other properties since they could not return to Romania while the war lasted.

At the end of World War I, large numbers of Romanians in Cleveland and other American cities hurried to return to Great Romania in the hope that with their hard earned American dollars they would be able to insure for themselves a carefree life. However, on arriving in Romania, many people became convinced that life in Great Romania was not like life in a free America.

St. Mary’s parish in Cleveland lost half of its members during the immediate postwar years. However, with the gradual return from Romania of former parishioners, St. Mary’s parish in Cleveland once again was placed in a more favorable position to develop its services and enlarge its facilities. In time a parish house and a recreation hall were erected.

After the return to Romania of Father Ilarie Serb in 1914, the parish was served by the following priests until October 1, 1928 when Father John Trutza became paster: Fathers Octavian Muresan, Teofil Rosca and Ilie Pop.

With the coming to Cleveland of Father John Trutza, St. Mary’s parish evolved a new and vigorous life. Under Father Trutza’s guidance a number of auxiliary groups were formed within the church to help maintain and raise the spiritual, cultural and social standard of the parishioners. Father Trutza helped to organize the National Organization of Romanian Orthodox Youth. He helped to make a name for the Romanians of Cleveland by his participation in civic affairs.

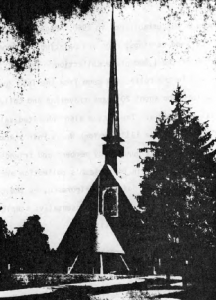

In March 1954 the former Regnatz property at 3256 Warren Road was purchased for $100,000 and work to build a new church began.

The new church is modeled after a traditional wooden church seen in the mountain districts of Transylvania. The cost exceeded $400,000 which included the cost of the cultural building adjacent to the church. The school building has 12 rooms to serve the educational needs of about 185 Sunday school pupils.

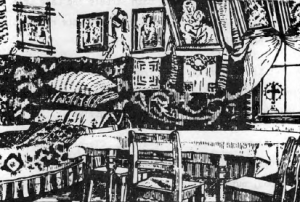

Parishioners of St. Mary’s Orthodox Church in Cleveland are particularly proud of the beautiful ethnographical and folk art museum located on the second floor of the cultural building. This is the only ethnographical museum of such dimensions in America and the only Romanian one outside Romania.

The museum was established in 1960. Peasant costumes, weavings, embroideries, wood carvings, rugs and paintings by Romanian masters form the core of the 1,000 piece collection. The first important group of items in the collection came from the late Mrs. Anisoara Stan of New York who spent 20 years traveling and collecting folk art material in Romania. The museum also inherited valuable pieces (copper plates) from the 1939 New York World Fair’s Romanian Pavillion. The rest was donated by members and friends of St. Mary’s parish. Also noteworthy in the museum’s collection are works by Romania’s most celebrated painter, Grigorescu; by the country’s foremost sculptor, Oscar Hahn and representative samples of paintings by Luchian and other Romanian artists.

Besides the unique ethnographical museum, St. Mary’s parish boasts a library of 2,000 books in the Romanian language.

Since the greatest progress in the life of St. Mary’s parish came during the pastorate of the late Father Trutza, it is only fair to mention that the church committee, under the presidency of Virgil Suciu was a most valuable ally of this distinguished leader. After serving St. Mary’s parish for 27 years, Father Trutza died on December 11, 1954.

In 1955, Father Vasile Hategan was called to Cleveland from New York where he served for 14 years as pastor of St. Dumitru Romanian Orthodox Church. He is the first Romanian Orthodox priest in America born in the United States. He pursued his theological studies in Romania and was ordained into the priesthood in New York by the late Archbishop Athenagoras, who later became world famous as the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople (Istanbul).

St. Mary’s parish is under the jurisdiction of the Romanian Orthodox Episcopate of America, headed by Archbishop Valedan Trifa, with offices in Jackson, Michigan. The Episcopate was established as a Diocese on August 25, 1929 at a general church congress held in Detroit. Administratively, the Episcopate is governed by the church congress and the Episcopate Council, both presided over by the bishop and constituted from representatives of the parishes.

Canonically the Episcopate is under the jurisdiction of the Orthodox Church in America. “Solia,” the official organ of the Romanian Episcopate; is printed in both English and Romanian.

Besides St. Mary’s, there is a smaller Romanian Orthodox parish in Cleveland, known as Bunavestire Church. This parish was organized in 1936 when a small group separated from St. Mary’s to form their own congregation. Their present location is at 3300 Wooster Road. Canonically Bunavestire Church is under the jurisdiction of the Romanian Orthodox Missionary Episcopate of Detroit which, until recently was under the Romanian Patriarchate of Bucharest, Romania.

St. Helena’s

Religious life for Romanian Catholics of Byzantine Rite in the United States began with the formation of St. Helena parish in Cleveland on November 19, 1905. The term “Catholic of Byzantine Rite” has been used in the United States only in the past two or three decades. When the first Romanians started coming to Cleveland in the 1900’s, members of this faith were known as Uniates signifying that they were united with Rome. Their religious services, language and church customs were, however, similar to the Eastern Orthodox.

The Uniate Church in Transylvania was established in 1700 but it remained in a minority compared to the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Like all Romanian immigrants to this country, the Uniates also considered the formation of parishes and churches one of the first priorities in their new land.

Interestingly, the Romanians were assisted in their endeavor by a Hungarian Catholic priest, Father Carl Boehm, pastor of St. Elizabeth Church on Buckeye Road, the first Hungarian Catholic Church in this country. Father Boehm noticed on his many visits to hospitals that the number of Romanians in Cleveland was growing. He informed Bishop Fredrick Horstman, head of the Cleveland Catholic Diocese of this and suggested that the Romanians be helped to organize a parish of their own.

In due time the Romanian Uniates contacted Bishop Horstman and asked his help. It just so happened that a Diocesan Seminary professor, Father T. C. O’Reilly remembered that while studying in Rome, he became acquainted with a Romanian seminarian “who should be graduated this year.”

Based on this information Bishop Horstman wrote to Bishop Vasile Hossu in Blaj, Transylvania and asked that this young seminarian be sent to Cleveland, after his ordination to the priesthood.

Bishop Hossu sent Father Epimamonda Lucaciu to Cleveland in the fall of 1905. Father Lucaciu, son of a Romanian national hero in Transylvania, was well known among Romanians for his fight for the Romanians’ rights in Magyar-ruled Ardeal.

Father Lucaciu was 28 years old when he arrived in Cleveland. Under his guidance the first Uniate Romanian parish was organized under the patronage of Saint Helena on November 19, 1905.

John Dringu and Marcu Lazar Were authorized to compile a list of all Romanian Uniate faithful in Cleveland and a church council was elected: Father Lucaciu, president; John Coman, treasurer; John Vladutiu, secretary; and Ovidiu Borza, Ilie Lupu, Nicolau Lupescu and Vasile Vinti, curators. Ion Aron, Ioan Carja, Nicolau Doctor, Petru Campean, Nicolae Lupu, Costache Caplea, Petru Minai and loan Serban were elected senators in the church council.

At this first meeting it was decided that the monthly membership dues be 50 cents “if he can afford it.” In 1905 the average daily wage for the immigrant worker was ten cents per hour.

In reporting the formation of the new Romanian Uniate parish, the Catholic Universe in its issue of December 1, 1905 wrote:

The only Romanian priest of the Greek-Uniate Rite in Ohio is Dr. Epimamondas Lucaciu, D.O., a brilliant young clergyman who arrived in Cleveland a few weeks ago with the purpose of organizing a parish among his own people in this city. Father Lucaciu is only 28 years old and has spent most of his life, as student and priest, in Rome. He speaks several languages, conversing in Latin as fluently as if it were his mother tongue and is rapidly familiarizing himself with English.

With a loan of $1,800 from Bishop Horstman, the young parish purchased a lot at 1367 W. 65th Street.

At the meeting of the new parish on December 25, 1905 the treasurer reported $208 in the bank. The church council was so happy about Father Lucaciu’s work that it awarded him a monthly salary of $30, with the proviso that in case the treasury got poorer, this salary would be “open for new negotiation.”

On May 24, 1906 the church council, headed by Father Lucaciu as president and Ion Aron, the cantor, as vice president, signed a contract with a builder for the erection of the church to cost $5,000.

While the new church was being built Father Lucaciu conducted religious services in a nearby Roman Catholic Church.

The History of St. Helena Church, published in 1911 mentions that in the early years of the parish, there was a bitter controversy between the Uniates and the Orthodox; the controversy was led by Father Moise Balea, an Orthodox, on one side and Nicolau Barbul, a Uniate, editor of “Romanul” on the other.

Father Lucaciu left St. Helena parish on December 29, 1907 for Aurora, Illinois where he organized a Romanian Uniate parish.

He was succeeded in Cleveland by Father Alexander Nicolescu, a distinguished professor from the Blaj Seminary in Transylvania. He was a man of superior culture and spoke several languages, among them English. He served St. Helena Parish until July 4, 1909.

During Father Nicolescu’s pastorate the United States suffered one of its most serious economic depressions. Romanian immigrants of that period were reluctant to apply for any aid anywhere. They were ashamed of their poverty and hunger was not far from the door of many. From his own resources and with the aid of understanding friends Father Nicolescu was able to provide free loaves of bread to his needy parishioners. Often Romanian families had nothing else to eat but the loaf of bread provided free by Father Nicolescu.

Meek and unassuming, Father Nicolescu helped to organize Romanian Uniate parishes in Youngstown, Alliance and Farrell. Returning to Transylvania in late 1907 he was appointed archdiocesan secretary and then bishop of Lugoj and Metropolitan of Alba Iulia-Fagaras, the highest post in the Transylvanian Romanian Catholic Church of Byzantine Rite. He died in Blaj in 1941.

Father Nicolescu was followed in the pastorate of St. Helena parish by Father Aurel Hatiegan, a well educated and pleasant young priest. Much of the progress of the parish occurred during Father Hatiegans’ tenure.

After World War I he planned to return for a visit to Romania. On the way to embark on a ship in New York he died suddenly on March 3, 1921. He is buried in the cemetery of St. Basil Uniate Church in Trenton, New Jersey.

Father John Spatariu served the parish from July 10, 1922 to September 23, 1928; and Father Victor Vamosiu from March 1930 to May 1933. On July 1, 1934 the leadership of the parish was assumed by Father George Babutiu, the first American born Romanian Uniate priest, who received his ecclesiastical education in Rome.

Besides his work with St. Helena parish, Father Babutiu was a strong supporter of the Cultural Association of Americans of Romanian Descent and was greatly responsible for the success of the organization’s publication, “The New Pioneer.”

After the totally unexpected death of Fr. Babutiu in 1950, Father Mircea Toderici became pastor of St. Helena and was still serving the parish in 1975.

When the posts of the parish priests of St. Helena were vacant, the parish was under the leadership of Father John Vanca, the venerable pastor of Most Holy Trinity Romanian Catholic Church of Byzantine Rite on Cleveland’s East Side.

During the pastorate of the various priests, numerous improvements were made on the buildings of St. Helena Church, parish house and recreation hall. A large recreation hall was added to the parish facilities during 1975.

Most Holy Trinity Church

The second Romanian Catholic Church of Byzantine Rite is Most Holy Trinity Church, formerly of 2650 E. 93rd Street, serving Romanian Catholics living on Cleveland’s East Side. The church has recently been moved to the Far East Side.

Most of the East Side Romanians came from the counties of Bihor, Satmar, Salaj and Maramures, situated on Romania’s western border, next to Hungary.

East Side Romanians settled in the midst of the Buckeye Road Hungarian neighborhood because many of the Buckeye district Hungarians had come here from the same general area from which the East Side Romanians came. It was natural that old neighbors and friends would gravitate to the same vicinity.

The history of Most Holy Trinity Romanian Catholic Church of Byzantine Rite is closely associated with the name of the late Father John Vanca who organized the parish in 1912. Father Vanca was known for his tireless work in bringing the East Side Romanians together. He was a kind and generous man whose tolerant attitude toward all religions was well known.

The old church building was dedicated July 4, 1916 and its parish hall served for many years as the social center of East Side Romanians.

In recent years the neighborhood around the church has lost most of its Romanian population, necessitating its move. The old time Romanian settlers and their American-born children followed their Hungarian neighbors to the southeastern suburbs.

The Cleveland Romanian Baptist Church

The only protestant denomination among Romanians in America is the Baptist. The Cleveland Romanian Baptist Church (established in 1912) is located at 1416 W. 57th street.

The first Romanian of Baptist faith in the United States was Teodor Selegean who arrived in Cincinnati on July 19, 1903. He was followed by Dumitru Neag who also settled in Cincinnati.

The small group of Romanian Baptists in Cincinnati became affiliated with the Lincoln Park Baptist Church under the leadership of a Romanian, Reverend Rista Igrisan, a native of Pecica, County of Arad in Transylvania.

By 1910 the little Romanian Baptist group grew to 48 members and they organized their own congregation. They bought a church building for $4,500 at 1991 Central Street in Cincinnati. This was the first Romanian Baptist Church in America.

As more Romanian immigrants arrived in this country, the number of Romanian Baptist groups also grew. Slowly but steadily, Romanian Baptist congregations were established in more cities. Most of the founders and early members of the Baptist churches came here from the western fringe of Transylvania.

The largest Romanian Baptist group is in Detroit, with three churches. Other Romanian Baptist centers are in Cleveland, Akron, Chicago, Gary, Alhambra and Riverside, California and Hamilton and Windsor, Ontario.

Little Romania

The West Side neighborhood along Detroit Avenue, which in time developed into a “Little Romania,” was predominantly Irish when the Romanians started coming in the early 1900’s. Relations between the older Irish and the newcomers were strained to say the least. It is said that Irish children threw stones at the Romanian “greenhorn” who, the Irish said “could not even speak English.” Eventually the Irish accepted the Romanian neighbors in a happier spirit.

In many instances genuine friendship developed between the Irish and the Romanians. A good example is the story of Marty Kilbane, an Irishman who acquired so many Romanian friends that he learned to speak Romanian fluently. It was a daily sight to see Marty go to the offices of “America,” the Romanian daily, buy the day’s issue and in the evening read it to his Romanian neighbors.

Kilbane’s knowledge of the Romanian language and his friendship with the Romanians served him well when he became a teller in the bank at the corner of Detroit Avenue and W. 65th street.

Until the 1950’s the land between W. 45th Street and W. 65th Street on both sides of Detroit Avenue was a self-contained “Little Romania.” Without walking more than 15 minutes from their homes, Romanians could find facilities that satisfied all their physical and spiritual needs.

The Romanian language daily “America” and the national fraternal organization, Union and League of Romanian Societies, were formerly located at 5705 Detroit Avenue, an address known to every Romanian in the United States. If a Romanian wanted to find the whereabouts of a friend or relative, an advertisement in “America” would surely bring results.

The two basic Romanian organizations were first housed in a frame structure built in the 1900’s. A modern, stone and brick addition was erected next to the old building in the 1930’s but in the 1950’s both buildings were sold for economic reasons. The sale of this property coincided with the diminishing membership in the Union and League and reduction in the number of “America” subscribers.

Presently, the Union and League has offices in the Williamson Building in downtown Cleveland and “America,” the semi-monthly, is printed in Detroit.

That Little Romania was indeed self-contained is illustrated by the following items.

St. Mary Romanian Orthodox Church was located at 6201 Detroit Avenue. When a new church was built at 3256 Warren Road, the old St. Mary’s was sold to a Russian Orthodox parish consisting mostly of post-World War II immigrants.

St. Helena Romanian Catholic Church of Byzantine Rite was located at 1367 W. 65th street. The parishioners decided to remain at the old place and today the group is enlarging the social facilities of the parish.

The Romanian Baptist Church is still located at its old place, 1416 W. 57th Street.

No story of the Cleveland Romanians can be written without mentioning the old “Carpatina” Hall, 1303 W. 58th Street. Carpatina Hall was not only the home of the fraternal lodge of the same name, but, in the old days, the social center of young and old Romanians of Cleveland. Many a brilliant ball was held there, and Romanians from allover Ohio gathered there to enjoy the concerts and plays given on the Carpatina stage. Artists from Romania always found a warm welcome there, and could be assured of a full house for any and every performance. Jim Popa, a good shoe repair man by trade, was leader of the popular Romanian orchestra which played in the Carpatina Hall.

Romanian grocery stores, butcher shops and other businesses were not only places of commerce but also social centers where shoppers exchanged news and gossip. Following is a list of Cleveland Romanian merchants in the 1920’s who helped make Little Romania a world unto itself.

Bakers: Dan Radu, Carpatina Hall; George Beldean, Herman Avenue and W. 53rd street.

Bankers: Dan Barza, Romanian Savings and Loan, 5501 Detroit Avenue; Elie Barsan, Pioneer Savings and Loan Company, 6701 Detroit Avenue.

Barbers: George Vuje and John Lengel, 5509 Detroit Avenue; Costica Vasilescu, 1282 W. 58th Street.

Bookseller and music supplier: George Motoasca, 5218 Detroit Avenue.

Confectioners: John Streza, 1344 W. 58th Street; John Steff, Herman Avenue and 65th Street.

Doctor: Dumitru Albu, Detroit and 65th Street.

Grocers and butchers: John Coman and Julius Ersay, Detroit Avenue and W. 52nd Street; John Catana and John Cismas, 1297 W. 57th Street; Mircea Luca and Ilarie Heprian, 1338 W. 58th Street; Samoil Milea, Herman Avenue and W. 65th Street; John Paraschivescu, 5426 Detroit Avenue; George Voik, Tillman Avenue.

Restauranteurs and tavernkeepers: Mihail Barza; John Cracium, 5535 Detroit Avenue; Alex Gabriel, 5415 Detroit Avenue; John Sherb, 5709 Detroit Avenue.

Shoemakers: Nick Mihaltian, 5105 Detroit; Mike Vulcu, 1368 W. 54th Street.

Tailors: S. N. Barbul, 5818 Detroit Avenue; John Rothman, 5308 Detroit Avenue.

The Boardinghouse

Young Americans of Romanian descent today find it hard to comprehend the hardships experienced by the early immigrants, between 1895 and 1914 when large scale immigration ceased.

Take, for instance, the history of the Romanian boardinghouse, the first social and commercial enterprise catering to the needs of the immigrants from Transylvania, Bucovina and other Romanian lands.

To fully understand the role of the boardinghouse in the lives of the Romanian immigrants it is important to note that in the early days of immigration most of the Romanian newcomers were male adults. Fear of an unknown new country, uncertainty for the future and the fact that most Romanian immigrants intended to stay in America only a few years were a few of the reasons why most immigrants came to this country without their families.

The few Romanians who brought their wives with them soon discovered that keeping a boardinghouse for their co-nationals brought in more money than working (at times irregularly) in factories. However, considering the long hours of work necessary to take care of 20-30 boarders and the lack of labor saving machinery, the boardinghouse keeper did not have an easy life.

The average Romanian boardinghouse was a two-story frame building with seven or eight rooms. The building was usually near the factory district, in Cleveland, near the factories located north of Detroit Avenue in the general area of W. 65th Street.

On the ground floor of the frame building were a large kitchen, a large dining room and the “front parlor.” On the second floor were the bathroom and the bedrooms.

The average number of residents in a Romanian boardinghouse ranged from 20 to 35, but in a few instances the number hovered around 50. This meant that practically no one slept alone in a bed and that often day and night shift workers in turn occupied the same bed.

The boarders knew each other’s names and were familiar with the Old Country villages from which each had come. Village loyalty was very strong among those who came from the same community in Romania. Later, when fraternal benefit lodges were organized, the people from the same village or county usually voted for candidates for lodge offices who were from the same village.

There were two kinds of boarders: those who lived “in company” and those who paid full board, called by the newcomers as “foreboard.” The company boarders paid $3 monthly each, for bed, washing and cooking, with the cost of food divided among members of the company. The foreboard man paid from $8-$12 monthly for lodging, laundry and three meals a day. The foreboarders were considered the aristocracy of the immigrants.

The boarders carried their lunches to their workplaces in “pails” which were made ready the preceding evening, except for the coffee. A typical lunch pail consisted of black coffee, two sandwiches or two slices of bread, one pork chop or sausage, one pickle; two eggs and an apple or a banana.

Except on Sunday and Monday mornings, breakfast in the average Romanian immigrant boardinghouse in Cleveland usually consisted of beef stew or scrambled eggs and coffee.

Regular Sunday noon fare was noodle soup and meat, homemade bread (in the very early days) and pork meat with dumplings. On Sunday evenings the Romanian boarders usually ate meat with sauerkraut.

Friday nights in some Romanian boardinghouses the usual fare was sausage with puree of dried white beans (rasole frecata). The usual evening meal on other days consisted of soup and fried meat or stew.

If a boarder wanted to wash down his evening meal with other than water, he could get from the boardinghouse keeper portions of “cow-and-calf,” meaning whiskey and beer which cost five cents for the whiskey and five cents for the beer.

When at home, the boarders ate at a long oilcloth-covered table that stood in the middle of the dining room, seated on long benches on either side of the table. Before each meal the oldest man present usually recited the Lord’s Prayer.

At the end of the month the boardinghouse keeper bought a four-gallon keg of beer and treated his boarders to free beer. This gesture, known in Romanian as cinste, was a regular feature of every boardinghouse. If some boardinghouse keeper forgot this duty, he soon lost some of his boarders.

After supper the men gathered around the long dining room table on which they put a three-gallon keg of beer and read letters received from home or sang the plaintive Romanian songs called doine. Some men improvised poems and sang the words to the tune of some well known doina. These poems usually expressed great nostalgic sadness about living in a strange country, far away from family and friends.

In every Romanian boardinghouse there was someone who could play the shepherd’s flute. He was the most sought-after man in the group since he was useful not only at regular get-togethers but also at such important events as weddings and christenings.

Besides the man who knew how to play the shepherd’s flute, another boarder who played an important role in every immigrant boardinghouse was the letter writer. He wrote the letters for those in the house who could not write well. The same man was also the one who was asked to read the letters which came from the Old Country.

Most Romanian immigrants made great efforts to save money out of their meager earnings, usually not more than $1.50 per day. Each resident in a Romanian boardinghouse kept a wooden box under his bed. In this he kept a slab of smoked bacon which he ate sitting on the bed. He often kept his money in the box, because few immigrants trusted banks in those days.

When a group of boarders decided to move to another boardinghouse, the moving was accompanied with music, the boarders marching down the middle of the street, led by a flute-playing friend.

The story of the immigrant boardinghouse would not be complete without emphasizing the extraordinary hard work of the boardinghouse keeper’s wife. Doing the laundry for 30 men, without labor saving machines, preparing every night, after supper, the lunch pails for 20-30 people and raising a family in addition to this made for extremely long working hours for the couple keeping a boardinghouse.

Life for the early Romanian immigrant was hard. Many American-born youngsters of Romanian descent today enjoy a better life because their immigrant parents and grandparents worked unbelievably hard in their early years in this country.

The Saloon

After the boardinghouse, the second commercial enterprise undertaken by venturesome Romanian immigrants was the saloon, which the Romanians called salon. It was the only enterprise which required a relatively small investment and little experience. A man needed a decent reputation and about $300-$500 with which to pay the annual liquor license.

The building in which the saloon was located belonged to one of several brewing companies. The saloonkeeper had to pay the month’s rent on the first of the month, and the bill for the beer and the whiskey, at the end of every week.

The saloonkeeper did not need a bartender’s manual to please the appetites of his customers. There were only two kinds of drinks served: beer and whiskey. The prices were established by the breweries and were uniform in all saloons. Usually the beer cost five cents and a small glass of whiskey five cents.

It was in the saloon that the early Romanian immigrant worker found refuge and a place of rest. In his boardinghouse he often had to share a bed with another man; and, with 20-30 boarders in the house, there was not much chance for rest.

It was the saloon that served as the stage for many impromptu singing bouts, consisting of nostalgic doinas and irredentist patriotic songs expressing the bitterness of the Romanians against the foreign rule in their homelands: Hungarians in Transylvania and Austrians in Bucovina.

Like the boardinghouse keepers, the saloonkeepers became leaders in the growing Romanian immigrant community. The saloonkeepers learned English faster than the factory workers and they soon acquired a reputation for having useful contacts with local politicians, councilmen, policemen and similar officials.

Local politicians were especially glad to have the friendship of the saloonkeepers because the innkeepers were able to influence the neighborhood on any issue that came before the public.

Since the early immigrants did not trust banks very much, the saloonkeepers also played the role of the banker. They kept the immigrants’ savings in their strong boxes and also loaned money to Romanian customers for steamship tickets with which to bring spouses and relatives to America.

Every saloon had a larger room where weddings could be held. At times religious services were also celebrated here by priests who visited the town periodically. It was not until 1904 that the first “permanent” Romanian priests began arriving in America.

The very idea of forming some sort of organization for the aid of the sick and needy and for funeral expenses was born at meetings in boardinghouses and saloons. For many years most of the Romanian immigrants were young men without families. When someone died — and many were killed in work accidents — the surviving Romanians used to pass the hat to collect the $40 needed for funeral expenses.

A Romanian Wedding in 1905

In the early days of Romanian immigration nearly all the newcomers were young unmarried adult males between the ages of 17 and 28. Few married men brought their wives with them, mainly because the husband had money for only one fare.

It is easy to understand that the most appreciated, most important additions to any Romanian immigrant group were women. The unmarried young Romanian women who had the courage to come to America alone, did not stay single very long. There were plenty of suitors for each girl.

A wedding was quite an event among our early immigrants. It was not only a joyous occasion for the groom and the bride but also offered an opportunity to all members of the local Romanian group to relax and break the monotony of never ending lonely days.

There is no comparison between the Romanian weddings of 70 years ago and those of today. Like everything else in those days, the immigrants’ weddings were modest. To American-born grandchildren of Romanian immigrants, the stories of the early Romanian weddings are like fairy tales.

Seventy years ago invitations to a Romanian wedding were made by friends of the couple-to-be with personal calls on other Romanians living in various boardinghouses.

After the church ceremony the wedding feast was held in the nearby saloon’s largest room. The food and drink served were the same as that served at weddings in the Old Country: soup, stuffed cabbage and chicken stew or roast chicken, whiskey and beer.

Wedding gifts were usually cash. Most of the gifts were one dollar bills or silver.

Today’s Romanian weddings differ very little from American weddings. They roll out the white carpet from the altar to the church entrance with flowers everywhere; but the wedding gifts are not one dollar bills.

Mrs. George Goske, a school teacher in Parma, was Cornelia Porea before her marriage, daughter of early Romanian immigrants. She has written a vivid account of her parents’ wedding in Warren, Ohio about 70 years ago. The description fits any Romanian wedding of that era in any city.

Mrs. Goske writes:

Two 17-year-old girls in Agarbiciu, Transylvania, talked excitedly about the many stories they had been hearing from the few Romanian men who had just returned from America.

It seemed to the girls that everybody in America was rich.

One of the girls was Maria Fagetian, my mother, and the other girl was her friend, Anica Lazar. The girls came from large families and it was hard for their parents to feed six or seven hungry mouths.

After listening to the wonderful tales from rich America, the two girls decided to go to the United States.

Maria remembered that her uncles, Ion and Vasile Lupu were in Youngstown, Ohio and surely they would be glad to see her.

And so, in 1903 Maria and her friend Anita set out from Transylvania to America.

At that time the Romanian colony in Youngstown was small and was grouped around the saloon owned by a kindly hearted Saxon from Transylvania who spoke Romanian and who was helping Romanian newcomers find work and shelter.

Maria and Anica looked up the Saxon saloonkeeper who directed the two girls to the boardinghouse where the two uncles lived.

Maria thought herself quite fortunate when a German speaking family, Mr. and Mrs. W. D. O’Connor hired her as a maid at the “enormous” salary of $2.50 a week and room and board and a few clothes.

On her free half day Maria visited her uncles in their boardinghouse and in time met a young man, John Porea, who hailed from Medias, Transylvania.

When work became scarce in Youngstown, John Porea sought work in Cleveland but kept up correspondence with Maria in Youngstown. Wishing to wait no longer for Maria, John returned to Youngstown and the wedding date was set for August 5, 1905.

John Porea was 20 years old and earned $1.65 for a 12 hour workday. His wages were higher than the other Romanians who earned only $1.25 per day.

Maria, too, was given a raise by the O’Connor family and now she earned $3.50 a week.

The morning of August 5, 1905 was bright and clear and the two went to the courthouse for their marriage license. The clerk had difficulty with the spelling of the two names but eventually the license was issued.

Since there was no Romanian priest at that time in the town, the young couple was married by a kindly old Russian Orthodox priest. The procession from the church to the boardinghouse was short. There were just two horse and buggy carriages to carry Maria’s two uncles, the bride and groom and a friend of the groom, Laurentiu Dopu.

Neither Maria nor John had much money to buy fine wedding clothes. Maria wore a “Gibson” girl dress with a full skirt, large sleeves and a soft white collar. The dress was white with small blue flowers through it and her veil was topped with a large white wax flower. There was no bridal bouquet, yet the outfit was an expensive one, Maria thought. It cost $3.50.

John Porea wore his best dark suit and he bought a white shirt for the occasion, that cost him 50 cents. He felt elegant in his dark wedding suit; it cost $8.

The wedding feast was held in a large room lent for the occasion by a lady from Agarbiciu. Almost 200 people came to see an old fashioned Romanian wedding. A close relative, Theodore Coman and his wife, Sophia accepted to be the nashi or sponsors of the couple.

Among the wedding guests were many Romanians for whom this was their first opportunity to meet other Romanians from Transylvania. One woman created a small sensation with the “American” coat she wore. She was greatly envied by the other guests who were still wearing the clothes they had brought with them from the Old Country.

Before the feast began the newly married couple was taken to a nearby photographer for their wedding pictures. A number of these pictures were to be sent to relatives in Romania as proof that Maria married a handsome man.

Main dishes at the wedding feast were the traditional chicken stew (tocana de gaina) and stuffed cabbage. Then there were simple pastries and an Easter Bread kind of colac.

All Romanian weddings, to this day, have a master of ceremonies whose role is to praise the bride and groom and their families and to tell amusing stories about the bridal couple. In the case of John and Maria Porea, the master of ceremonies was Laurentiu Dopu who had watched over Maria ever since she came to America.

In his speech he told of the bravery of the bride who came alone to America to seek her fortune. Properly embellished, Mr. Dopu’s story brought tears to the eyes of the wedding guests. Mr. Dopu also spoke of the virtues of the groom and promised that both Maria and her husband would eventually return to Transylvania, with good reports about America.

When the toastmaster finished his speech, two men walked around the tables in the room to receive wedding gifts for the couple.

Modern married couples of Romanian descent who often get cash wedding gifts in the thousands of dollars, will be shocked to learn that John and Maria Porea on their wedding day in 1905 received the “magnificent” sum of $92 — after they paid the expenses of the wedding feast.

Most of the gifts were 50 cent pieces. The sponsors of the couple, Theodore and Sophia Coman, contributed $10 and there were two other gifts of $5 each. But it should be remembered that the wedding guests at that time worked for $1.25 a day.

The meal was accompanied by beer from several kegs and wine from a few five-gallon jugs. Two fiddlers and a clarinet player furnished the music for the Horas and the Sirbas danced with great enthusiasm by the participants.

The first thing purchased by Maria was a large table which cost 75 cents. This was the first piece of furniture the young couple bought for their two-room living quarters.

After a few years, John and Maria Porea went back to Transylvania for a few months but they returned to the United States. They found that the root of their married happiness was in America.

Today Romanian weddings are much like American weddings. But the wedding feast is usually held in a Romanian church hall, and the menu is sure to include stuffed cabbage, besides other foods. Also, after the bride and groom dance their first dance, the guests usually dance the Romanian traditional Hora, Sirba and Invirtita.

Funerals

In the early days of Romanian immigration, Romanian funerals were simple, cheap (around $100), and served to bring together all members of the Romanian colony whether they knew the deceased or not. Attending the funeral of a fellow Romanian was a must.

Wakes were held every evening, before the funeral. The religious part of the wake was called saracusta officiated over by a priest and a cantor. In the old days after the saracusta the men retired to a back room where they usually played cards until early in the morning. The women stayed in the room where the body was laid out and exchanged news and gossip.

Since there were few churches at the start of Romanian immigration in America, the funeral service was held at the home of the deceased. Before the casket was sealed, a photograph was taken. It was customary, and it is still so today, that from the cemetery the mourners returned to the bereaved family’s home to partake of the pomana, that is, remembrance feast. This was either a complete meal or just sandwiches.

At intervals of six weeks, six months and one year following the death, the family arranged for a requiem or memorial service called parastas held on Sundays in the church following the Liturgy.

After the parastas was over, a large cake-like bread was cut in small pieces and, with a little wine, offered to the people. As the people partook, they said, “May his soul rest in peace.”

Present day customs of the Romanians in America are greatly affected by social changes but in religious forms and customs the Romanians still cling tenaciously to their traditions.

The Two R’s

Most of the Romanians who came to America around 1900 could read and write well but some were not so fortunate. To this minority America gave a great gift: the opportunity to learn how to read and write. This was important for many reasons, not the least of which was that it enabled an immigrant to read personally the letters which came from the Old Country and to write replies without asking a more literate fellow boarder to do it.

Romanian peasant families in Transylvania and Bucovina were burdened with large families. In many households the children were needed to work on the fields and to care for the farm animals; schooling was secondary. School attendance was not enforced by the Hungarian and Austrian authorities who cared little whether their Romanian subjects attended school or not.

News of the world penetrated the villages slowly. Only a few persons in each village were regular newspaper subscribers. It was customary for small groups of villagers to meet on Sunday afternoons near the church or the school where a literate peasant or the teacher would read the newspapers aloud to the assembled.

This custom was continued to a certain degree in America, too, but it did not satisfy the Romanian newcomers. They wanted to read the papers themselves, and this is why the Romanian language publications were important.

As the number of Romanians in the United States grew, Romanian language publications began appearing like mushrooms after a good rain. Both competent and incompetent individuals who imagined themselves saviors of the Romanian nation initiated newspapers without having studied the economics of the publishing business. Consequently, many newspapers and magazines disappeared from the market.

The two newspapers which existed the longest were “Romanul” established in Cleveland by Father Epamimondas Lucaciu, pastor of St. Helena Romanian Catholic Church of Byzantine Rite, in 1905, and “America,” the weekly founded on September 1, 1906 by a newly arrived Romanian Orthodox priest, Fr. Moise Balea. The purpose of “America” was to give news and to “defend the principles of the Orthodox Church.”

Before “Romanul” and “America” saw the light of day in Cleveland, a man named Liviu Prasca of Cleveland organized a stock company in 1903 to finance the publishing of a Romanian language newspaper. When the stock was unloaded on the immigrants, Prasca disappeared with the money, and the paper, “Tribuna,” ceased publication.

From the beginning of large scale Romanian immigration to this country 75 years ago, 36 different Romanian language newspapers and magazines have been published in the United States.

With the gradual disappearance of the older generation, the number of Romanian publications sharply declined, and there are now only eight publications, five of which are official organs of churches and fraternal groups. None are dailies.

The oldest Romanian paper is “America” established in 1906, the official organ of the Union and League of Romanian Societies of America, headquartered in Cleveland. For about 30 years “America” was a daily; today it is a semi-monthly.

At the height of its prosperity, in the 1920’s, “America” as a daily had a circulation in excess of 21,000. Presently, as a semi-monthly, this figure is about 6,000.

The other good-sized semi-monthly Romanian publication is “Solia” (the Herald), issued by the Romanian Orthodox Episcopate in America at 11341 Woodward Avenue, Detroit. Circulation of “Solia” is also around 6,000.

The Association of Romanian Catholics of Byzantine Rite issue a semi-monthly, “Unirea,” at 2371 Woodstock Drive, Detroit. “Luminatorul” is a Romanian Baptist monthly, published at 9410 Clifton Boulevard, Cleveland. A relatively new semi-monthly is “Credinta,” organ of the Romanian Orthodox Missionary Episcopate, 19959 Riopelle Street, Detroit.

Privately owned are “Drum” (Road) quarterly, 215 Valley Drive, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Boian News Service, 300 E. 91st Street, New York, New York; and “Micromagazin” monthly, 18-47 26th Road, Astoria, New York.

The Arts

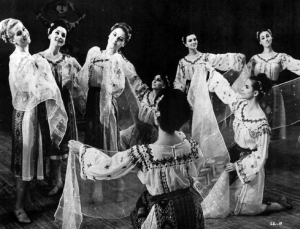

Before the 1930’s, when first generation Romanian immigrants were still living in relatively large numbers in Cleveland, Romanian language theatricals and concerts were great favorites of the Romanians.

Old timers in Cleveland today will remember the visits of the Ionescu-Ardeal theater group. The group gained wide popularity among Romanians here for their artistry and because they specialized in things artistic from Transylvania and Bucovina.

When Greater Romania became a reality at the end of World War I, Romanians in America were feverishly anxious to enjoy artistic programs presented by the new visiting Romanian artists.

Jean Nestorescu, a well known Romanian violinist came to America in 1921 and enjoyed a successful tour of many American cities. Cleveland Romanians were glad to see that Nestorescu settled here in 1922.

In January 1923 the famous Romanian composer, director and violinist, George Enescu arrived in this country and conducted symphony orchestras in New York, Philadelphia and other large American cities. He made his first appearance in Cleveland in February 1924 conducting the Cleveland Orchestra. During successive years Enescu visited Cleveland many times. Whenever he came Romanians from all over Ohio assured the Cleveland Orchestra of a full house.

More information on this great Romanian is presented in Chapter Nine. An imposing statue of Enescu can be seen in the Romanian section of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens. It is a gift of the present Romanian government and was brought to Cleveland be the Romanian Cultural Garden Association.

Although today’s English speaking young Americans of Romanian ancestry are not as familiar with Romanian music as were their grandparents and parents, nevertheless the orchestras playing at Romanian social functions still have a repertoire of Romanian dance numbers. It would be hard to imagine a Romanian dance today, with second and third generation Americans on the dance floor, without the traditional Romanian numbers such as the Hora, Invirtito, Batuta and Hategana.

\