Chapter 4: The Impact of Religion and Hierarchy on African Art

Chapter 4.6 Kingdom-based art

Larger states generally gained their territories through the exercise of power, and kept it through enforced taxation. A broad tax base enabled the central power to accumulate wealth, often expending it in ways that reinforced the members’ elevated status–dress, architecture, and large public ritual events. Wealth was accrued through agriculture and trade, or control of the latter with taxes or surcharges added.

The largest African states were in the savannahs on the desert fringe–areas that could feed themselves and support horses, enabling the central authority to collect taxes and keep borders secure. Many of these states, such as Mali, Bornu, or the Hausa kingdoms, were Muslim, but hierarchy still distinguished the nobility from commoners through architecture, household goods, and personal dress. Forest kingdoms, such as the two covered in this chapter, tended to be smaller because tsetse flies prevented horses from living long, and both trade and war required more strenuous passage through the forest, as well as the risk of foliage serving as enemy cover. Forest kingdoms, however, were fertile suppliers of foodstuffs and also often stockpiled valuable goods such as ivory, kola nuts, or other items in high demand. Social hierarchy was expressed artistically in additional ways that included hieratic scale in sculpture, extensive use of figurative sculpture in wood, terracotta, and more luxurious materials, and the adoption of motifs, object types, or fabrics that reflect novelties resulting from long-distance trade.

Kingdoms may appear to be led by a single individual, but courts also consist of advisors and attendants with positions that run from minor to very major indeed. Art has often been used to reinforce such hierarchies, distinguishing the monarch from even his highest chiefs through ranked levels in architecture, jewelry, textiles, and particular materials. Many kingdoms had or have sumptuary laws that outline who is permitted to wear what (or build what), with consequences for those who attempt to flout regulations.

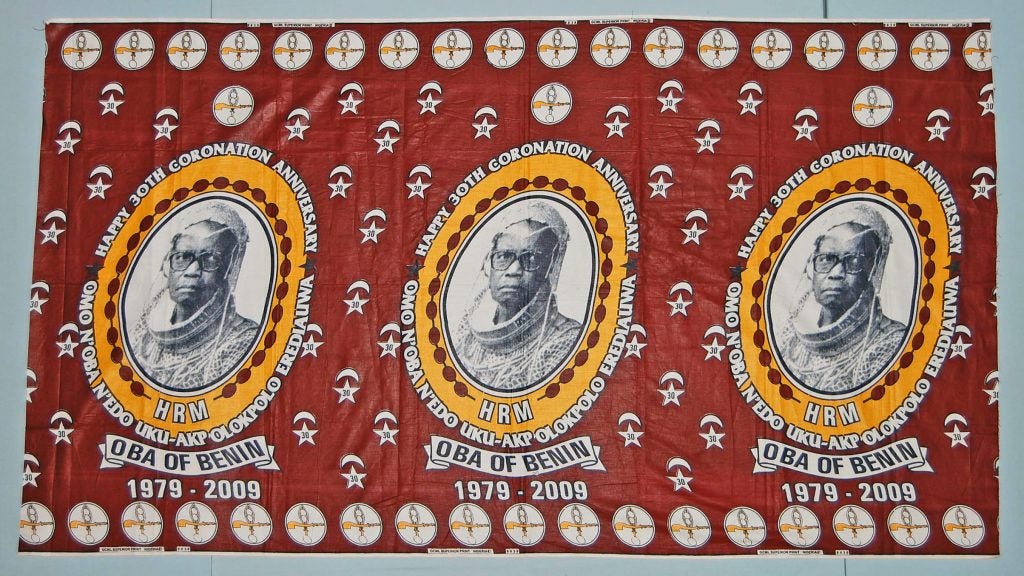

With the advent of European colonialism, rulers were stripped of their powers to tax their own people, wage war, carry out capital punishment, and enforce laws relating to major crime disputes. In some polities, such as the old kingdom of Dahomey, monarchs had their titles taken away, and were permanently dispossessed of their palaces (Fig. 813). In other states–particularly those colonized by the British–monarchs retained their titles, palaces, and the right to settle land disputes and minor cases. They were paid like formal civil servants, a practice that continued after independence. In Nigeria, monarchs are ranked as first, second, or third-class traditional rulers, receiving stipends from the government as well as overseas medical check-ups, vehicles, and other gifts that vary according to their status. Although their civic powers are sharply diminished, they retain a great deal of spiritual and royal authority, and are still major patrons of the arts, receiving additional income through land distribution, arrangements with corporations within their domain, and appointments to various companies’ boards-of-directors.

The Asante State

The Asante had one of the best-known empires in West Africa, with art that was primarily made to support the state and an individual’s status within its hierarchy. No masquerading occurs, and figurative sculpture was limited, consisting primarily of wooden fertility figures (Chapter 3.3), combs (Chapter 3.2), and occasional maternity images, as well as funerary terracotta portraits (Chapter 3.7).

Birth of Asanteman (the Asante State)

In the year 1600, southern and central Ghana was occupied by numerous ethnic groups, as it is today. Many of these peoples–especially those living in the central or western areas of the coast

and inland, shared a common language, and many traditions. Although all of them are Akan peoples who speak Twi, they were subdivided into independent small states that were frequently in conflict with one another. One state might vanquish another and force them to pay tribute until one day the tables would turn. One such group of Akan peoples were the Asante, who had been forcibly brought under the control of the Denkyira state to their southwest. The various Asante clans each had a head, as did the clans of their neighbors under Denkyira hegemony. In the late 1600s, one of the Asante leaders, Osei Tutu, had the close support of a powerful ritual specialist, Okomfo (priest) Anokye, who is said to have come from another region. All the Asante clans and those of neighboring groups met to decide on a leader and plan how they might defeat the Denkyira. To avoid internal discord, Okomfo Anokye announced that leadership would come from the heavens, and that a Golden Stool would descend onto the lap of the destined paramount ruler. It appeared and settled on Osei Tutu’s lap, confirming divine will, and he became the first Asantehene, or monarch.

To empower the stool and ensure that it represented the united state, Okomfo Anokye is said to have sacrificed a man and seven pythons who disappeared into the stool, then applied a concoction made from the attendant chiefs’ hair and nail clippings, binding their vows of loyalty to it. Stools are felt to absorb part of their owners’ souls; the Golden Stool represents the soul of the Asante nation, and is its most sacred symbol. No one sits on it; it has its own throne and is rarely seen, creating a powerful mystique (Fig. 814). Its symbolic supremacy is still expressed through textiles, paintings, and sculpture (Figs. 482 right and 815).

Okomfo Anokye insisted those under him bury their state swords–a symbolic gesture that acknowledged their fealty–and inserted a state sword in the spot where it happened, stating that as long as the sword remained there, Asante would prosper (Fig. 816). In 1701, Osei Tutu I and Okomfo Anokye defeated the Denkyira, wresting their control over the coastal town of Elmina, one of the Akan kingdoms settled by the Fante. Elmina had become a major overseas trading state, for the Portuguese–who had reached the region in 1471–had erected a stone fort there in 1482. By Osei Tutu’s time, the Dutch had taken it over. With Denkyira’s defeat, the Asante had an international trade outlet and expansion of the state through acquiescence and conquest quickly expanded the kingdom’s borders beyond those of the Asante until they controlled much of inland Ghana and part of its coast. The byproduct of expansion was the enslavement of those who fought the kingdom, a factor that saw many 18th-century Akan sent to Brazil, Surinam, Jamaica, the United States, and other destinations in the Americas. Some populations, such as the Baule, fled in advance of Asante growth, migrating into what is now Côte d’Ivoire.

Foreign interest in the region was centered on gold, and the Asante controlled its alluvial extraction, preventing European penetration from the coast for centuries. While considerable raw gold was exported to Europe, the Asante retained and worked gold in the form of cast jewelry and gold foil-covered wooden objects, its possession and display governed by rank. Because of European thirst for gold, they had traded arms to obtain it, and the Asante were well equipped with guns and gunpowder.

By the beginning of the 19th century, the English were the key stakeholders along the coast and at Accra, with the exception of Elmina. In an effort to collect intelligence and manipulate the Asantehene into creating a road to Cape Coast and signing a treaty with the British, they sent Thomas Bowdich to Kumase. In 1817, he became the first European to enter the Asante capital. His first impression of the royal quarter’s splendor was as follows:

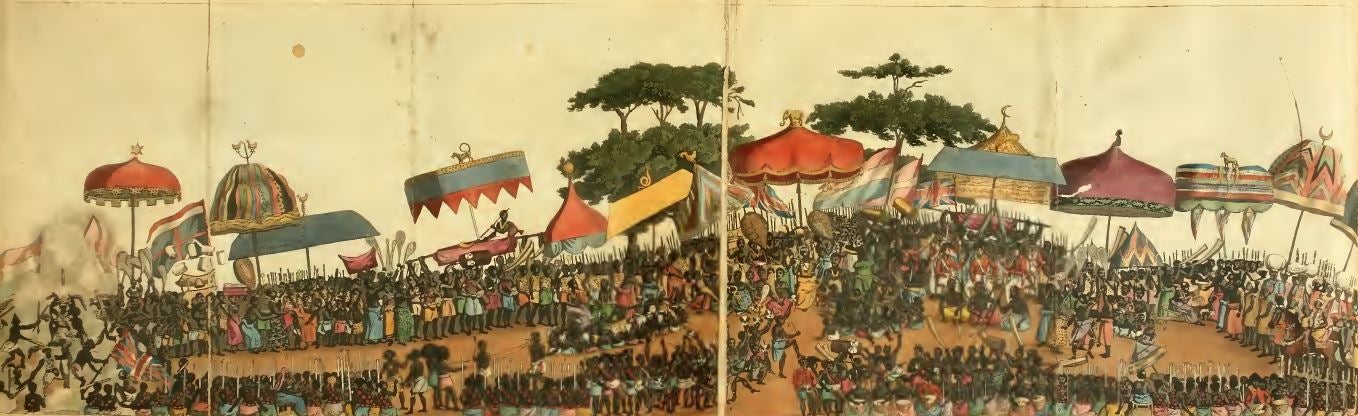

“an area of nearly a mile in circumference was crowded with magnificence and novelty. The king, his tributaries, and captains, were resplendent in the distance, surrounded by attendants of every description, fronted by a mass of warriors which seemed to make our approach impervious. The sun was reflected, with a glare scarcely more supportable than the heat, from the massy gold ornaments, which glistened in every direction . . . At least a hundred large umbrellas (Figs. 817 and 818), or canopies, which could shelter thirty persons, were sprung up and down by the bearers with brilliant effect, being made of scarlet, yellow, and the most shewy [sic] cloths and silks, and crowned on the top with crescents, pelicans, elephants, barrels, and arms and swords of gold; they were of various shapes, but mostly dome; and the valances (in some of which small looking glasses were

inserted) fantastically scalloped and fringed; from the fronts of some, the proboscis and small teeth of elephants projected, and a few were roofed with leopard skins, and crowned with various animals naturally stuffed . . . The caboceers [officials], as did their superior captains

and attendants, wore Ashantee cloths, of extravagant price from the costly foreign silks which had been unravelled to weave them in all the varieties of colour, as well as pattern; they were of an incredible size and weight, and thrown over the shoulder exactly like the Roman toga; a small silk fillet generally encircled their temples, and massy gold necklaces, intricately wrought;

suspended Moorish charms, dearly purchased, and enclosed in small square cases of gold, silver, and curious embroidery. Some wore necklaces reaching to the navel entirely of aggry beads [expensive glass beads made in West Africa]; a band of gold and beads encircled the knee, from which several strings of the same depended; small circles of gold like guineas, rings, and casts of animals, were strung round their ancles [sic] (Fig. 819); their sandals were of green, red, and delicate white leather; manillas, and rude lumps of rock gold, hung from their left wrists, which were so heavily laden (Fig. 820) as to be supported on the head of one of their handsomest boys. Gold and silver pipes, and canes dazzled the eye in every direction. Wolves and rams heads as large as life, cast in gold, were suspended from their gold handled swords, which were held around them in great numbers; the blades were shaped like round bills, and rusted in blood; the sheaths were of leopard skin, or the shell of a fish like shagreen (Fig. 821) . . . [the king] wore a fillet of aggry beads round his temples, a necklace of gold cockspur shells strung by their largest ends, and over his right shoulder a red silk cord, suspending three saphies [Islamic charms, purchased from peoples to the north] (Fig. 822) cased in gold; his bracelets were the richest mixtures of beads and gold, and his fingers covered with rings; his cloth was of a dark green silk; a pointed diadem was elegantly painted in white on his forehead; also a pattern resembling an

epaulette on each shoulder, and an ornament like a full blown rose, one leaf rising above another until it covered his whole breast; his knee-bands were of aggrey beads, and his ancle strings of gold ornaments of the most delicate workmanship, small drums, sankos, stools, swords, guns, and birds, clustered together; his sandals, of a soft white leather, were embossed across the instep band with small gold and silver cases of saphie ; he was seated in a low chair, richly ornamented with gold; he wore a pair of gold castanets on his finger and thumb, which he clapped to enforce silence. The belts of the guards behind his chair, were cased in gold, and covered with small jaw bones of the same metal; the elephants tails, waving like a small cloud before him, were spangled with gold (Fig. 823), and large plumes of feathers were flourished amid them. His eunuch presided over these attendants, wearing only one massy piece of gold about his neck: the royal stool, entirely cased in gold, was displayed under a splendid umbrella, with drums, sankos, horns, and various musical instruments, cased in gold, about the thickness of cartridge paper: large circles of gold hung by scarlet cloth from the swords of state, the sheaths as well as the handles of which were also cased; hatchets of the same were intermixed with them: the breasts of the Ocrahs [young male attendants who purified the monarch’s soul], and various attendants, were adorned with large stars, stools, crescents, and gossamer wings of solid gold” (Bowdich, 1819, pp. 84-89).

The Architecture of the Past

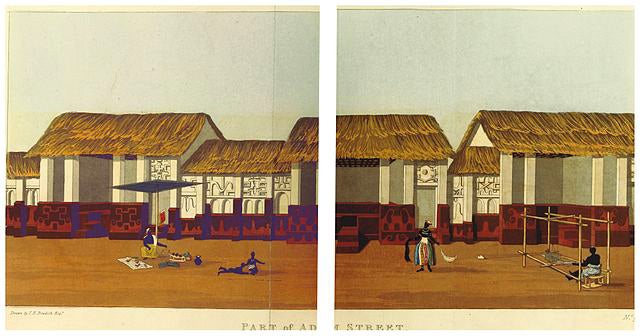

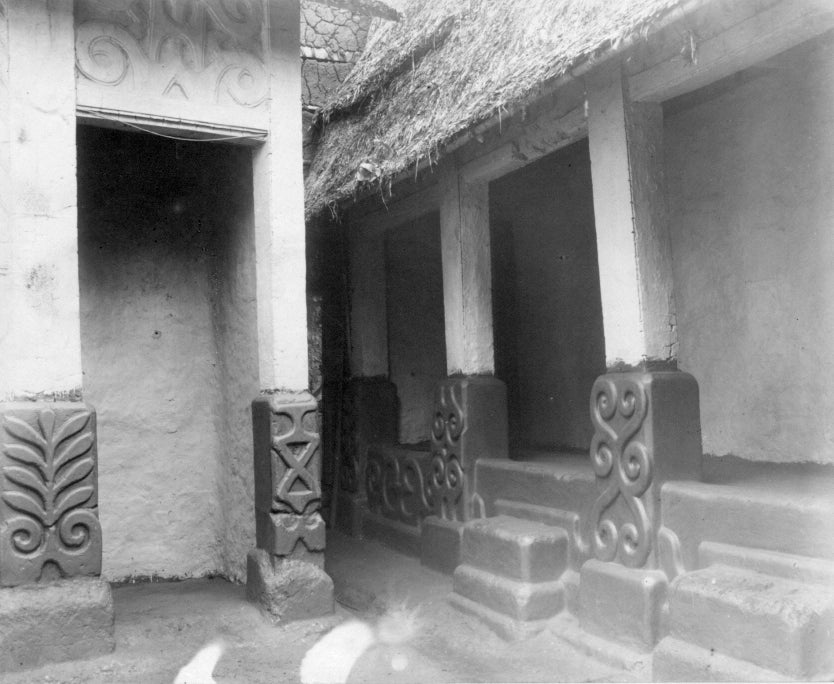

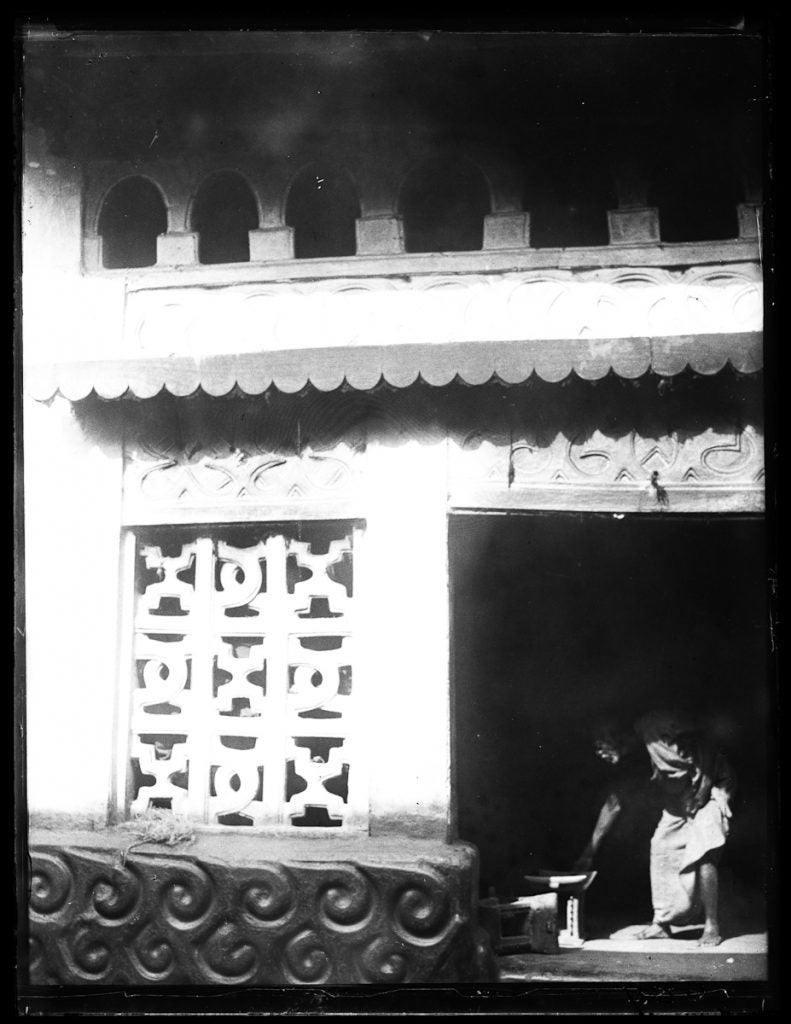

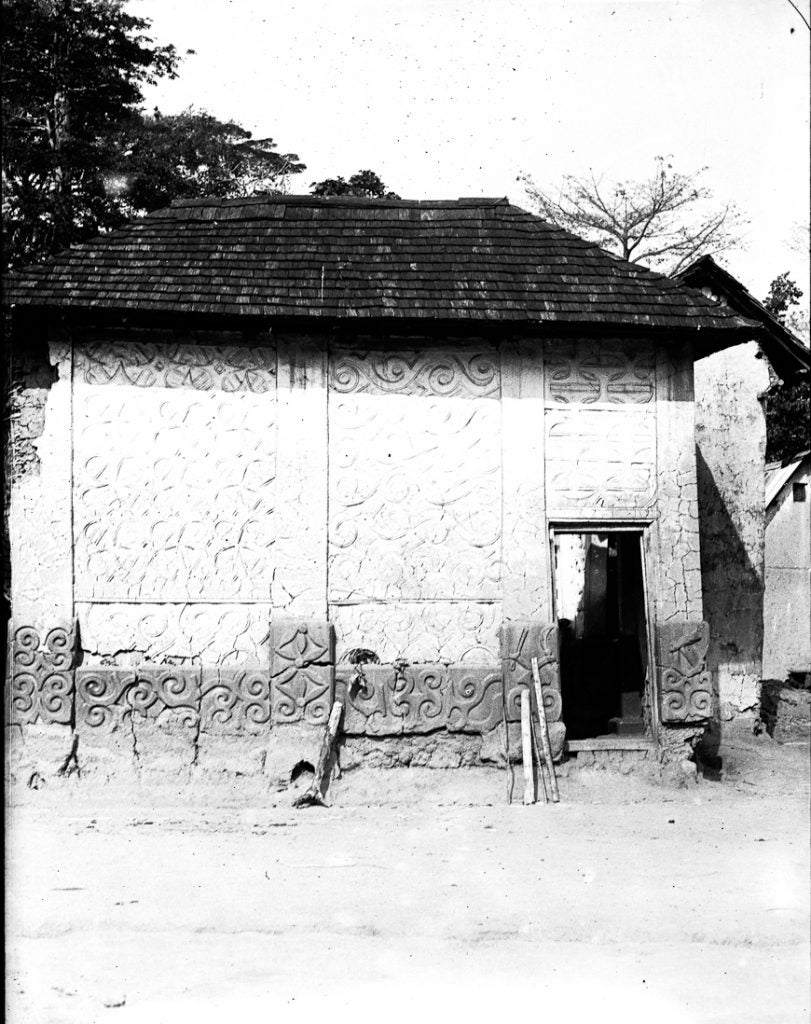

The Kumase Bowdich saw was an elegant city. Made from earth-filled and finished reed constructions, houses were white-washed with chalk, composed of courts without windows on their outward exteriors, which provided privacy (Fig. 824). Many aristocrats occupied two-story homes, which were unusual in pre-colonial Africa, requiring reinforcement through interior pillars. Only the nobility had open rooms on the street side of their houses (Fig. 825). These semi-public spaces allowed them to be accessible to clients and observe the activities of the neighborhood. Wealthy homes included relief decoration on their surface, formed by packing reeds into the mud of the wall when it was wet, then using more clay to plaster over the form.

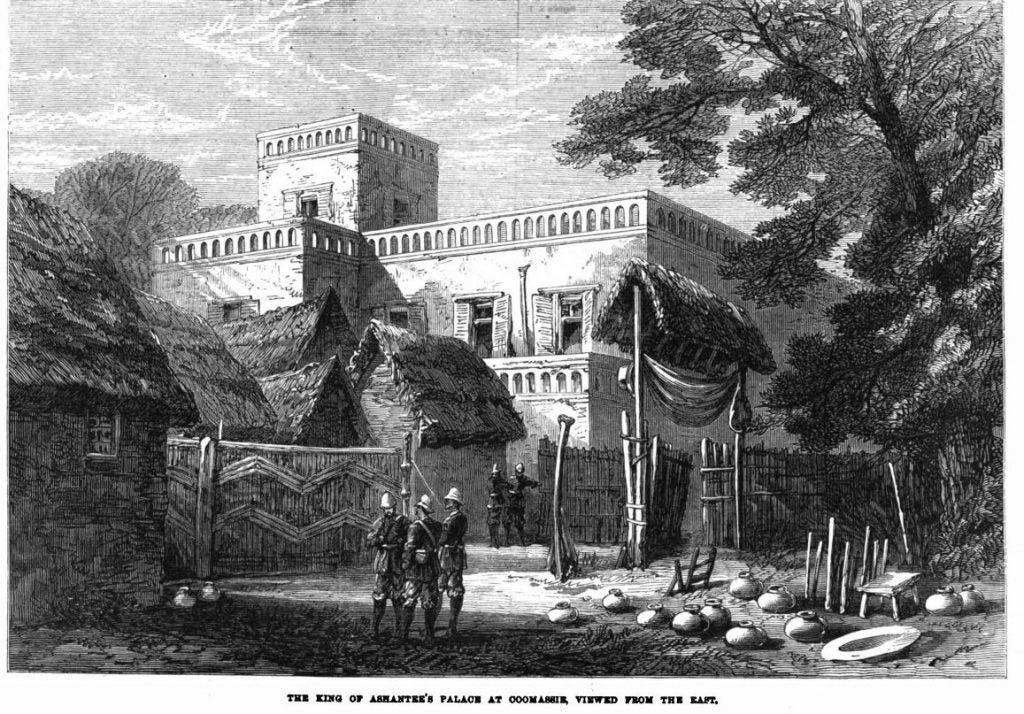

The palace covered five acres, consisting of multiple courts composed of the standard four rooms placed around a central courtyard. It differed from ordinary homes by its scope, functions, and decoration, not its design. Some palace courtyards could hold 300 people, and Bowdich noted the presence of the “King’s garden, an area equal to one of the large squares in London.”

The Asantehene discussed ambitious building plans with Bowdich, mentioning a proposed new residence with a brass roof, ivory pillars, and gold window and door trim. After looking at prints and drawings of European buildings, he finally decided to add a two-story European-style stone structure that acted as museum and storehouse (Fig. 826), rather than living quarters. Elmina craftsmen, used to constructing such buildings, carried the stones

The pillar supports display multiple symbols, some of which still appear on adinkra stamped cloth and contemporary architecture. The leafy form at the extreme left is known as asaya or fern, and is variously interpreted as a symbol of endurance or defiance. National Archive, UK. CO 1069-34-122. Public domain.

from the coast to Kumase, about 140 miles away.

The British, eager to have exclusive trading rights with the Asante and get access to the direct source of gold, tried to enforce the treaty Bowdich had persuaded the Asantehene to sign. This led to a string of five wars between the British and the Asante in the 19th century; there had been several earlier conflicts regarding coastal settlements. The Asante vanquished the British at several key battles, but when the latter invaded Kumase in 1874, they looted the Asantehene’s stone structure of its gold artifacts, then leveled it with dynamite, also destroying many of the palace’s older clay structures. The rebuilding of the latter took place immediately (Fig. 827), but struggles over the monarchy had returned both the palace and Kumase to a state of disarray within a decade. Continued conflict with the British led the Asantehene Prempeh I to be deposed and exiled in 1896, the palace left in disrepair. In 1901, an ill-advised visiting British Governor of the Gold Coast demanded the Golden Stool be brought out for him to sit on, precipitating the Queen Mother of one of the Asante towns to rally troops and hold the British in a two-month siege. When it ended with the arrival of troops from the coast, the British had finally established colonial rule after a long period of resistance.

When they finally felt comfortable in their control, they allowed Prempeh I to return to Ghana, then to Kumase. Initially, they referred to him as a private city. They then refused to acknowledge him with his actual title, referring to him as Kumasihene, or ruler of Kumase. Finally, they accepted the public insistence on his position as Asantehene. The year after they built a two-story stone house for the British Governor in Kumase, the same foreign construction company erected a new palace for the Asantehene (Fig. 828), but they located it in a former suburb, since the old palace site had been built up as a commercial district in the intervening years. The new palace had a two-storied symmetrical style like that of the governor’s house, though the British consciously made the palace slightly smaller in an attempt to impose their own hierarchy and authority and supplied a columned portico instead of the governor’s arched entryway. The Asante footed the bill, which amounted to 3000 pounds (the equivalent of about $250,000 today). In the early 1970s, soon after Asantehene Opoku Ware II came to the throne, he built a new palace next door in the then internationally-popular concrete Brutalist style. The current monarch, Asantehene Osei Tutu II, renovated it after he came to the throne in 1999 (Fig. 829), changing its facade to an arched exterior similar to the old colonial governor’s house.

The Splendor of Gold and its Place in the Hierarchy

The foundation of Asante wealth was the gold whose extraction they controlled. Gold dust was common currency, and even at the beginning of the 20th century, young men who were getting married were given a set of brass goldweights, scales, spoons, and storage boxes to countercheck those of merchants. Goldweights were in existence throughout Akan territory since at least the 15th century. They were made to set measurements, and encompassed a greater range of subject matter than most African traditional art, ranging from the strictly geometric patterns that seem to have been the earliest type (Fig. 830) to objects from daily or palace life to complex, almost anecdotal depictions of individuals, objects, or animals in action (Fig. 831).

One type of brass vessel served as larger containers for gold dust. The forowa, usually a round lidded object made from sheet brass (Fig. 832), was more often used to hold shea butter, a cosmetic pomade, but it could be used to store medicinal substances, currency, or beads.

Gold served as foreign exchange, but much of it was used for regalia at the royal courts of both smaller Asante states and at Kumase. Goldsmiths were expert at working the soft metal, flattening it into thin sheets that could be applied over wood or casting it in the lost wax method (Fig. 833).

Its prestige enhanced a multitude of items. Bowditch referred to some of the window

frames of Kumase aristocrats being rimmed with gold, while even the humble calabash could become ennobled by flattened gold wire decoration (Fig. 834). State objects either included gold ornaments–rifles often had gold additions on their stocks–or were made of wood covered with sheet metal. These included both objects assigned to key courtiers or those used for the ruler. Often these decorations were visual versions of proverbs meant to remind rulers or the public of certain realities, admonitions, or desired behavior.

Sheet gold-covered finials decorate the huge parasols of state umbrellas belonging to paramount chiefs (Fig. 835). This depiction of a porcupine encapsulates two proverbs symbolic of the Asante state, which was formulated as a warrior state–the very word “Asante” is said to mean “because of war.” Both proverbs refer to the porcupine’s quills as innumerable, like warriors: “Kill a thousand, a thousand will come” and “The porcupine fights from all angles.”

A set of officials (okyeame) found at both the Asantehene’s court and lesser Asante courts are responsible for both the implementation of proper protocol and the diplomatic relaying of messages between the ruler and supplicants. Wooden staffs topped by proverbial imagery–again, carved from wood and usually covered with sheet gold–act as their badge of office at public ceremonies (Figs. 836). This example, once attached to a long wooden rod, includes a common image still found on many staffs. It depicts two men seated on Akan stools seated at a table that bears a bowl of food; one reaches to eat, the other looks at him thoughtfully. This illustrates the aphorism “Food is for the owner, not the hungry man.” This is an admonition to those who coveted the kingship. The Asante do not inherit from father to son; as a matrilineal society, titles pass from uncle to a maternal nephew, but there is no automatic choice through seniority. The Queen Mother–who may be the actual mother of the late ruler, or a relative on his

mother’s side that he appoints to that position after his actual mother’s death–plays a vital role in the choice of the next ruler, and plays a vital advisory role during her reign. The finial’s figures show head-to-body proportions that are close to 1:7, but still elongate the neck to an unrealistic length. The neck is creased–an attractive trait here, as it is in Sierra Leone and many parts of West Africa–and the men in suits have faces that are far less flat than those of the aku’aba fertility figures or terracotta heads. The okyeame usually have a group of staffs at hand, the property of their matrilineage, and select whichever one they feel is most appropriate to a given occasion. Today some of these proverbial finials are painted rather than gold-covered (Fig. 837), and their staffs may likewise be painted with metallic paint.

As previously mentioned, state swords–which are both carried in processions before a ruler and rested against his palanquin or litter–have their own proverbial cast gold ornaments (Fig. 838). These can be exquisite in execution (Fig. 839); this spider example alludes to Ananse, the Asante trickster hero of folk tales. Many proverbs refer to Ananse; a different but popular depiction of a spider in a web (that is, an expert spinner/weaver) equates to

the English saying, “Don’t try to teach your grandmother to suck eggs,” scolding someone for

presuming to offer advice to someone with more experience.

The bulk of gold was meant for personal adornment at public occasions, and it still fulfills that role (Fig. 840). Both an expression of wealth and power and an expression of spiritual vitality, it marked rank

and protected it. Rulers’ regalia, as well as that of their family and attendants, were adorned with it, as the latter reflected the prestige of the former. Rings (Fig. 841), bracelets (Figs. 842 and

843), and necklaces were worn in abundance by those of high standing, and were melted down and recast when change was desired.

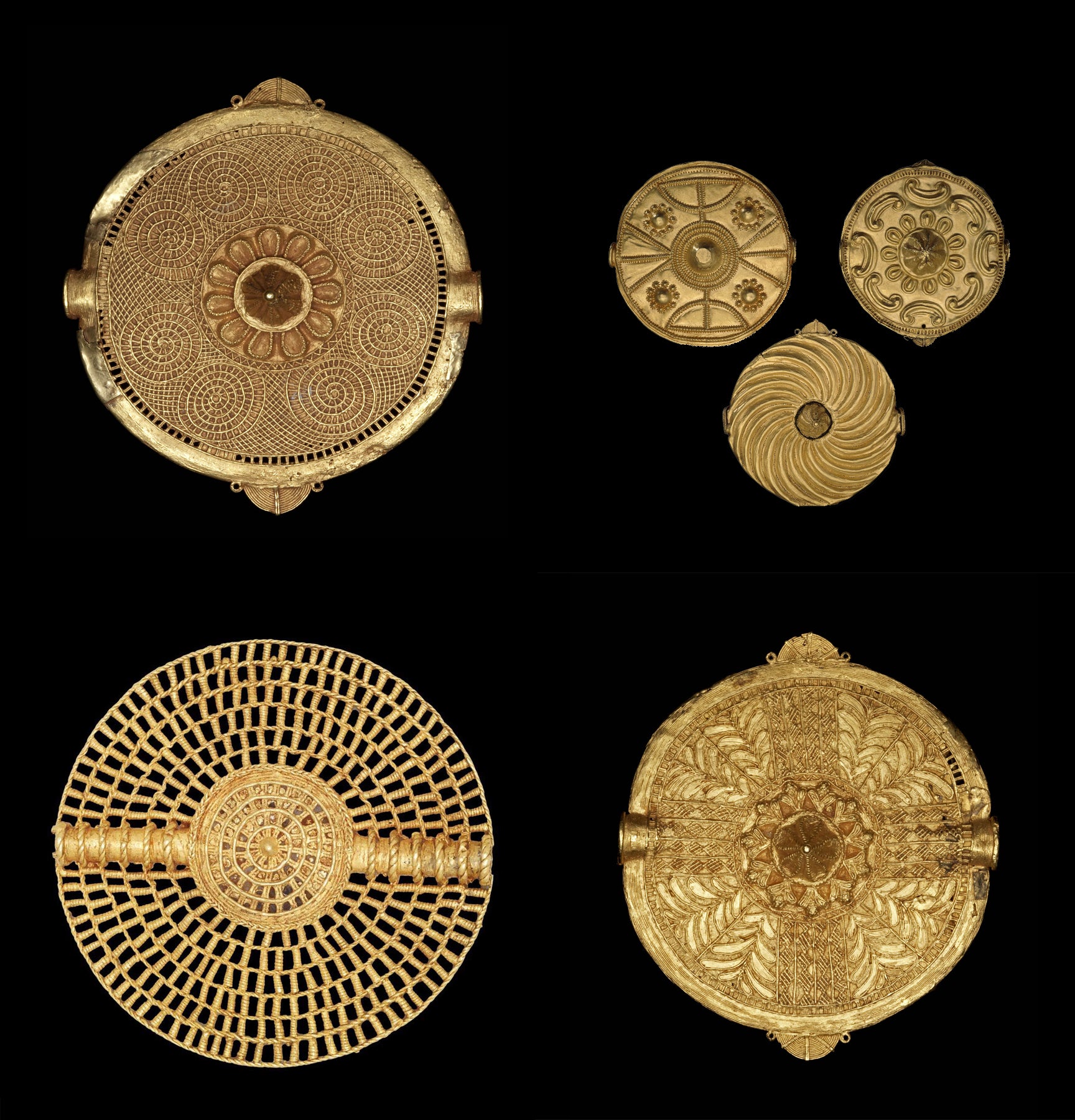

One expression of the goldsmith’s skill was the so-called soul washer’s badge (akrafokonmu), a circular pendant suspended on the chest from a cord. Sun-like, its decoration took many directions. Individuals who wear it can be male or female, and included several high-ranking courtiers, such as some swordbearers (Fig. 844). They are particularly associated with the okra (“soul washers”), good-looking young people who were born on the same day as the ruler, offered him some spiritual protection, and were charged with the duty of renewing his soul through specific rites.

Doubled akrafokonmu are worn by female courtiers who hold the royal flywhisks, but they are increasingly seen at funerals. The chief mourner often wears two, suspended side-by-side. Their shape and central projection heighten their resemblance to abstract breasts, representing the fertility of the ruler and the abundance of his matrilineage. In independence-era Ghana, there has been a democratization of certain objects and materials formerly restricted to the nobility–at least outside the immediate palace environment–that are become prominent at times of family display, such as female puberty rites, maternal public outings after a first birth, and funerals. The double-disc necklace is now often the gift from one spouse to another when the recipient’s parent dies, in consolation for that individual’s now-parentless status (Fig. 845).

All akrafokonmu discs, which can be smithed or cast, exhibit a multitude of types of decoration (Fig. 847). Their techniques vary–some are cast, while others are repoussé sheet gold Some are purely geometric in their motifs, while others incorporate references to ornate European patterns of the late 18th and early 19th century, a period when a desire for trade brought many luxury imports to the court.

Swathed in Substance and Meaning

Jewelry is not the only status marker that distinguished the dress of the ordinary Asante person from that of the nobility. Many aspects of dress were also subject to sumptuary laws, as well as affordability. Today many of the rules governing dress have relaxed, and daily clothing, as opposed to court attire, may be sharply differentiated, but prestige attire can still be distinguished. Sandals, for example, are an everyday item for many (Fig. 848) today, though in centuries past many individuals walked barefoot. Examples bearing gold ornaments or wooden ones covered with gold foil are still worn at ceremonial occasions by rulers–whose feet are forbidden to touch the ground–and their chiefs(Fig. 849). At palace occasions, one removes one’s sandals before approaching an individual of higher rank as a mark of respect.

Sandals, like so many items that make up Asante regalia, often have proverbial associations. In a formal procession, a ruler’s courtiers display his various sets of sandals as they walk before him, conveying a variety of non-verbal messages. These sandals can take on even more fanciful formats, as their leather soles are sometimes cut in the shape of animals (Fig. 850). Some show further status escalation, the leather itself being covered in sheet gold (Fig. 851).

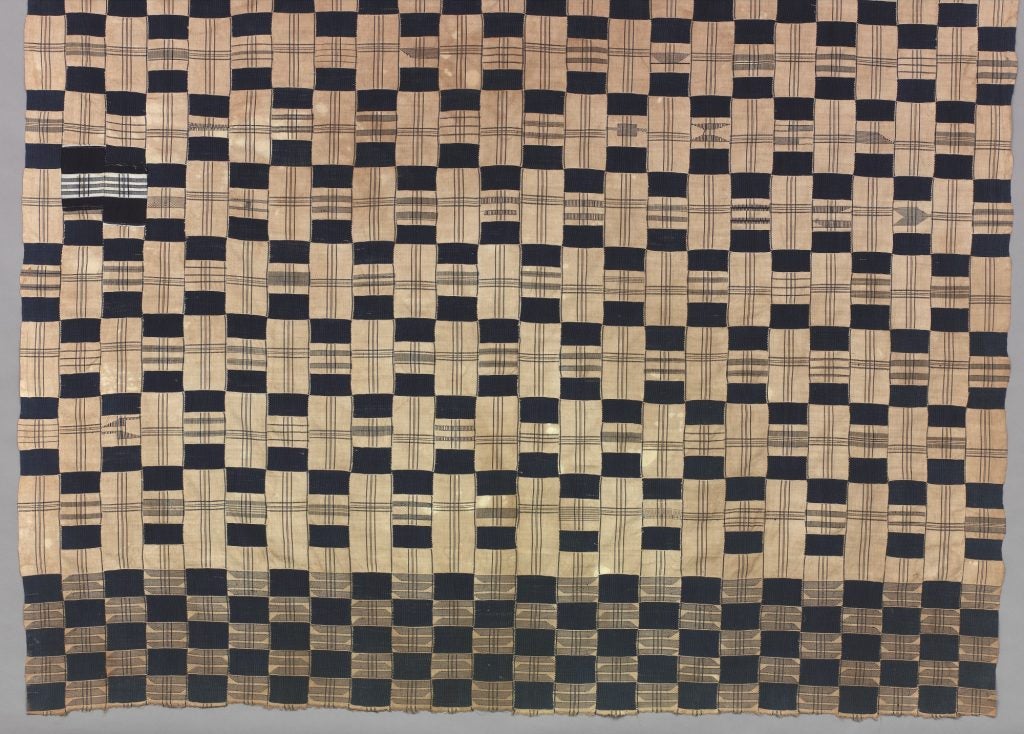

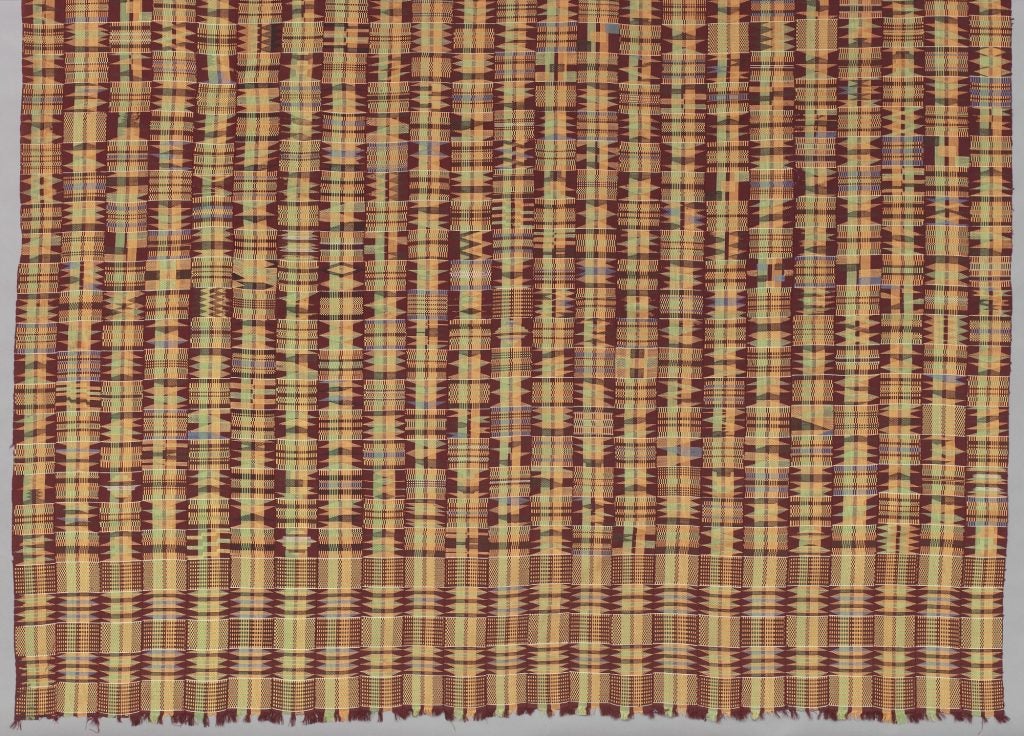

The Asante are known for their exquisite narrow-strip weaves, known as kente (Fig. 852). These include some of the most complex patterns in Africa, and are commonly made of cotton. Some, however, are made from silk, a practice that began centuries ago when imported silks were picked apart thread by thread in order to redye them and create textiles more satisfying to local tastes. Although these are still made, they very are expensive,

so rayon threads create a third version. The Asante sited the royal weavers at Bonwire, a village that is now a Kumase suburb. In centuries past, they produced certain cloths that were exclusively for the Asantehene, as well as others for royal family members and the nobility (Fig. 853). Each pattern has a name and symbolic associations, and over 300 exist. Since the early 20th century, kente‘s use has been democratized, and new patterns and color combinations continue to develop (Fig. 854). The most complex silk cloths remain costly, and are commissioned.

The proportions of finished cloths differ for men and women. Men’s cloths, worn by aristocrats like a toga over the left shoulder (Fig. 855), are generally about 8′ wide and 12’ long, while women can wear the traditional cloth tied above the breasts and falling to the ankles (sometimes with a shawl), as a waist-tied wrapper with a blouse or shirt, or tailored into a blouse and skirt.

Kente has become internationally known as not only a Ghanaian symbol, but more generally as a representation of Africa and African heritage internationally. This journey began as early as 1960, when head-of-state Kwame Nkrumah wore it in New York to address the United Nations, an event widely covered by the press. That year Ghana also gifted the U.N. with an oversized kente wall hanging, its pattern known as tikoro nko agyina, or “one head does not constitute a council.” The world-wide craze for kente peaked in the United States in the 1990s, when demand was so high that some Asante women at Bonwire defied tradition and began to weave like their brothers and fathers. Most abandoned this within a decade, due to social pressure and the production of printed imitation cloths.

A second type of valued cloth is adinkra, a cloth whose symbolic decoration is traditionally stamped onto a plain-colored cloth, which may be hand-woven or imported. Adinkra‘s origins are said to lie in the state of Gyaman, in what is now Côte d’Ivoire. Their ruler’s name was Nana Kofi Adinkra, and the Asante viewed his attempt to copy the Golden Stool an outrage. They conquered and annexed his state, bringing him to Kumase for execution, where his patterned cloth drew interest and is said to have developed into a new Asante textile form in the early 19th century. If this story is indeed true, it is puzzling, for the defeat of Gyaman is said to have occurred in 1819, yet Bowdich took home a heavily-patterned adinkra cloth (Fig. 856) from Kumase two years earlier. Whatever its origins, adinkra production is centered in the village of Ntonso, just outside Kumase.

Adinkra stamps (Fig. 857) are made from calabashes, and the dye that is used is made from a specific tree bark that is pounded in a mortar, then boiled down for a week until it has a tar-like consistency. Clothes are then sectioned off with a comb-like implement, and varied stamps traditionally are used to fill in the resulting rectangles (Fig. 858). Today stamps are larger than they were a century ago, and silk-screening with traditional dye is now the most popular technique to create wearable textiles; this also permits innovations in motifs (Fig. 859).

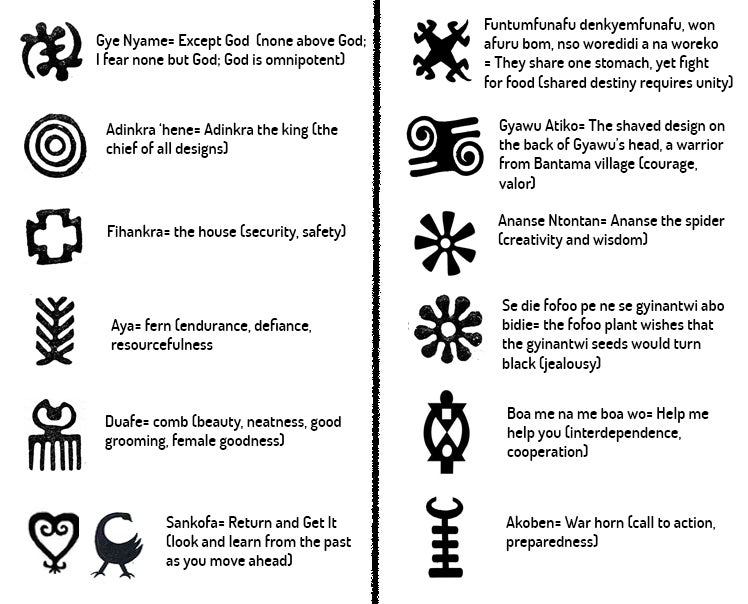

Nonetheless, the communicative symbols of the past are still extremely popular. Each has a name and, like other Akan arts, an associated proverbial meaning. While there are several hundred adinkra motifs, those in common use are more limited in number (Fig. 860). They form a symbolic vocabulary that allows dress to communicate, as does the background color of the chosen

cloth. Black or red adinkra cloths are used for funerals, while white or bright colors are used for celebratory purposes, including festivals and Sunday church services (Fig. 861). Because of their technique, even the most complex of these cloths are far less costly than kente.

Adinkra symbols have a life that has expanded throughout the Akan world, and appear on both old (Figs. 827and 862) and new architecture (Fig. 863), architectural features (Figs. 864, and 865), jewelry, plastic chairs (Fig. 866), and other domestic items.

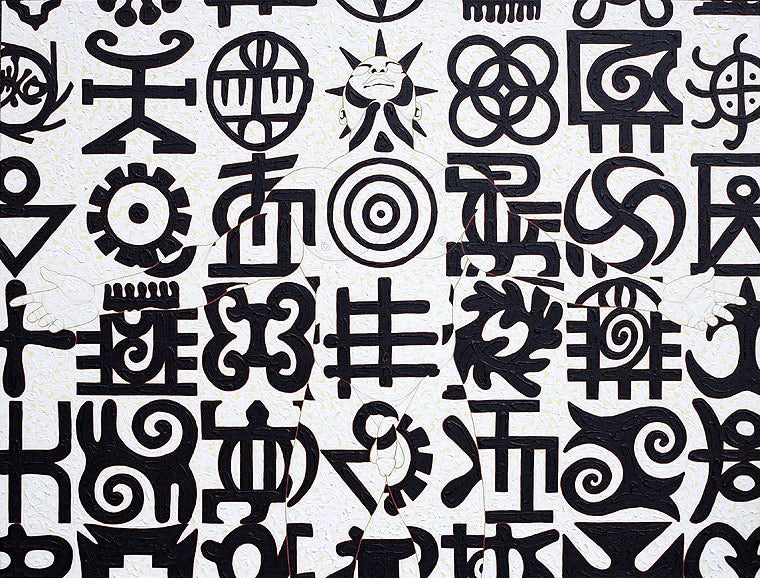

Adinkra iconography has become a regular feature of certain Ghanaian artists’ works. Several painters who teach or taught at Kumase’s Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) incorporate adinkra symbols into their non-objective works, either mixed with other motifs or as emblematic repeats that become the focus of the work.

Such artists may be well-known regionally and have influenced younger generations of painters; some have also garnered international recognition through overseas residencies and awards. Their external reputation as African contemporary artists, however, pales in comparison to that of Kwesi Owusu-Ankomah, and exemplifies how the internal/external directions of contemporary African art can affect artists of the same background but differing trajectories.

Owusu-Ankomah (who uses his surname exclusively) is an Akan artist who grew up in one of the Fante communities in coastal Ghana. He attended art school in Accra, then left for Germany when he was in his twenties, and has remained Bremen-based since then. There he developed his style that earlier featured monochromatic red or blue compositions with muscular human representations and rock art or adinkra references, and now concentrates on large-scale black and white canvases that include transparent, almost invisible, naturalistic and idealized male nudes that exist within a forest of flat symbols. The majority of these symbols are adinkra motifs, but Owusu-Ankomah is interested in graphic communication, and also includes road symbols, trademarks, Chinese ideograms, and Japanese kamon crests, among other signs (see here for the Mitsubishi trademark at right, or here for several mandalas).

His painting Free (Fig. 867) was one of three created for London’s October Gallery to commemorate the Bicentenary of the Parliamentary Abolition of the Atlantic Slave Trade in its exhibition “From Courage to Freedom” in 2007, its title a reference to Frederick Douglass’s 1845 autobiography. This exhibition, which also included commissioned works by El Anatsui and Romuald Hazoumé, is just one example of the high-profile projects the artist has been involved in. October Gallery, which represents Owusu-Ankomah, is one of the premier showcases for contemporary African art, and its imprimatur ensures the international museum and collectors’ world will be aware of its artists’ work. Owusu-Ankomah’s musings about global symbolic interconnectivity, philosophy, and beliefs in extraterrestrial impacts on pre-Egyptian cultures make him press-worthy, as does his extolling of the “microcron,” which he describes as “the symbol of symbols,” key to secret knowledge. In short, his access to the international art world (although he exhibits in Ghana as well) is extensive, sustained, and curated, bringing adinkra not only to museum galleries but to other popular spheres. Through the auction of his official painting Go For It, Stars (and its subsequent high-end art poster) he entered the sports world in the 2006 World Cup FIFA Art Edition Project, when Germany hosted the World Cup. The world of couture saw his entry when Giorgio Armani adopted his symbol designs for T-shirts in a 2007 (PRODUCT) RED collaboration intended to benefit the fight against HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis in Africa. High-profile projects like this have exposed adinkra motifs to more people than ever before, even if they cannot identify the symbols by name or meaning.

Seats of Power

The Asante, like most other Akan groups, consider stools to be something beyond places to sit, although most can also fulfill that basic function at one point in time. Domestic stools belong to an individual and are identified with that individual. When an Akan person sits on their stool, it is believed to absorb something of their

essence (sumsum), a phenomenon that increases with every use. When not occupied, stools are turned on their side so that malevolence cannot seat itself.

The intimacy between a stool and its owner is palpable. Ordinary citizens–men, women, and children–used to receive stools at key points in their life: at the point they began to crawl, demonstrating they survived the vulnerable stage of infancy, at the time of a girl’s puberty rites, at the time of marriage. Some of these practices have fallen by the wayside; puberty rites are not often practiced in the same way, with the girl seated on her new stool, for example. The basic shape–a monoxyl structure with a flat base, intervening support element, and a slightly curved, rectangular seat–is fairly consistent, but supporting elements have varied from the abstract to representations of persons, animals, and inanimate

objects. Particular shapes and decoration once gave some indication of ownership and occasion. Although some stools could be used by either gender (Fig. 868), a husband usually gave his new bride a stool with a perforated cylindrical support and pillars at the edges (Fig. 869). Size and other salient details differentiated these from others that might belong to specialized officials (Fig. 870), priests (Fig. 871) or chiefs (Fig. 872).

Chiefs’, rulers’, and queen mothers’ stools differ from those of ordinary citizens in type, purpose, and potential decorations. Most of all, they differ in intent, taking on a significance beyond that of the individual. Title stools represent a titled position and serve not only as a

throne but as a rallying point for community constituents. They embody the state, not just the titleholder. The Asantehene and other major rulers and their mothers own multiple stools of varying complexity, often carried before them in processions (Fig. 873). Some monarchs and queen mothers have stools decorated with gold or silver repoussé bands (Fig. 874); others bear attached bells and ornaments. A select few are more thoroughly metal-plated (Fig. 875) or

bear figurative or proverbial supports (Fig. 876). While most restrictions regarding sumptuary regulations are no longer in operation, state stools that appear to copy famous state stools would still be problematic, unlike those owned by ordinary people from once-forbidden designs.

In 1927, Rattray described 31 stool types and their meanings, noting he was only selecting a limited sample of a much larger stool repertoire. As the 20th century progressed, many more variations emerged: trucks, cocoa trees, drummers, and other subjects. While rulers and courtiers still regularly commission stools, those who are less palace-oriented do not buy them as frequently as they once did. Nonetheless, the stool as a symbol of unity and nationhood still stands, and has expanded into new environments. The entry gate of KNUST takes the shape of a stool (Fig. 877), as does the official office and residence of Ghana’s president (Fig. 878), the building called variously Flagstaff House or Jubilee House, constructed on the former administrative site of the colonial British Gold Coast government.

While new rulers’ ascension to their thrones is referred to as “enstooling,” rulers do not always sit on their thrones when they are on public display. Instead, one of several types of backed chairs is usually their seat of choice. These developed from different types of imported European wooden chairs whose leather seats and backs were attached with brass tacks, but they are lower than most foreign versions. These would have first been used at the coast, then traded inland and reproduced locally in both areas. Asimpim (Fig. 879) (“I stand firm”) are thought to be the oldest of the three. They are also the most common, owned by even minor rulers. Hwedom are similarly armless wooden chairs, but they are larger and painted black, their struts carved in imitation of lathe-turned wood, and usually bear silver or gold ornaments; the Golden Stool itself uses one as a throne (Fig. 814). The last takes the form of a European folding chair as its prototype, though it does not itself collapse. This is the akonkromfi (“praying mantis”) (Fig. 880); it and the hwedom are less common and used solely by those of highest rank.

Spiritual Spots and Substances

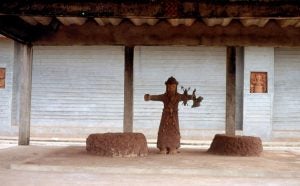

Akan traditional religion centers belief on the High God Nyame, and simple altars to him–composed of an offering bowl placed in the branches of a small stripped tree– were once ubiquitous.

Religious observances centered on other deities and the ancestors. Those deities most honored with temples and priests were those associated with the Tano River, whose source is in Techiman and flows southward, eventually forming the border between Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. Only ten of the old temples survive, and they now serve as both religious structures and museums under the protection of the Ghana Museums and Monuments Board (since the 1960s) and UNESCO’s World Heritage List. The key ingredient of shrines is a brass basin filled with sacred water, but kente cloth, state swords, and other regalia items also serve as decoration.

Shrines were built on the same model as the domestic house–four buildings around a courtyard. Exteriors might be whitewashed and plain (Fig. 824) or decorated with relief designs (Fig. 881). These structures had open porches on the interior (Figs. 882 and 883). One held drums, another shrine furniture, a third the shrine essentials. The kitchen rounded out the designated areas.

Free-standing sculpture was not a standard aspect of shrines, although they might serve as a repository for successful aku’aba fertility figures (see Chapter 3.3) or the occasional figure.

Because of the disruption and looting that took place during the Anglo-Asante wars and subsequent colonialism with wide-scale adoption of Christianity, the original function and location of the relatively few Asante figures are uncertain. This sculpture depicts an Asante Queen Mother (Fig. 884) seated on a throne, her sandaled feet elevated. She and her baby have slender bodies with elongated torsos and legs, their faces flattened like aku’aba figures, their simplified features stressing brows and nose in a similar way. Because the Asante are matrilineal, the female line is essential to royal continuity, and the Queen Mother’s political role is a critical one. This might have once stood in a shrine meant for a queen mother’s protection, or have been part of an ancestral stool room.

While stools in use–royal or not–are carved from light-colored wood, after death the stools of the great take on a religious function. Intentionally blackened by egg yolk

and soot, the stools of rulers, chiefs, and queen mothers are placed in a joint lineage stool room. After the death of their owners, they are consecrated and invoked, so that the activated souls of the deceased enter the stools and can remain active on behalf of the royal families. Blackened stools are the focus of offerings and prayers, providing protection to their descendants. Placed on their side on animal skins on an elevated earthen altar, they are removed and carried in public procession when another stool is added to their number (Fig. 885).

Further Reading

Appiah, Peggy. “Akan Symbolism.” African Arts 13 (1, 1979: 64-67.

The Benin Kingdom

Nigeria’s Benin Kingdom offers an unusual opportunity to examine the pace of change in African royal art, both in terms of object types and style, for it

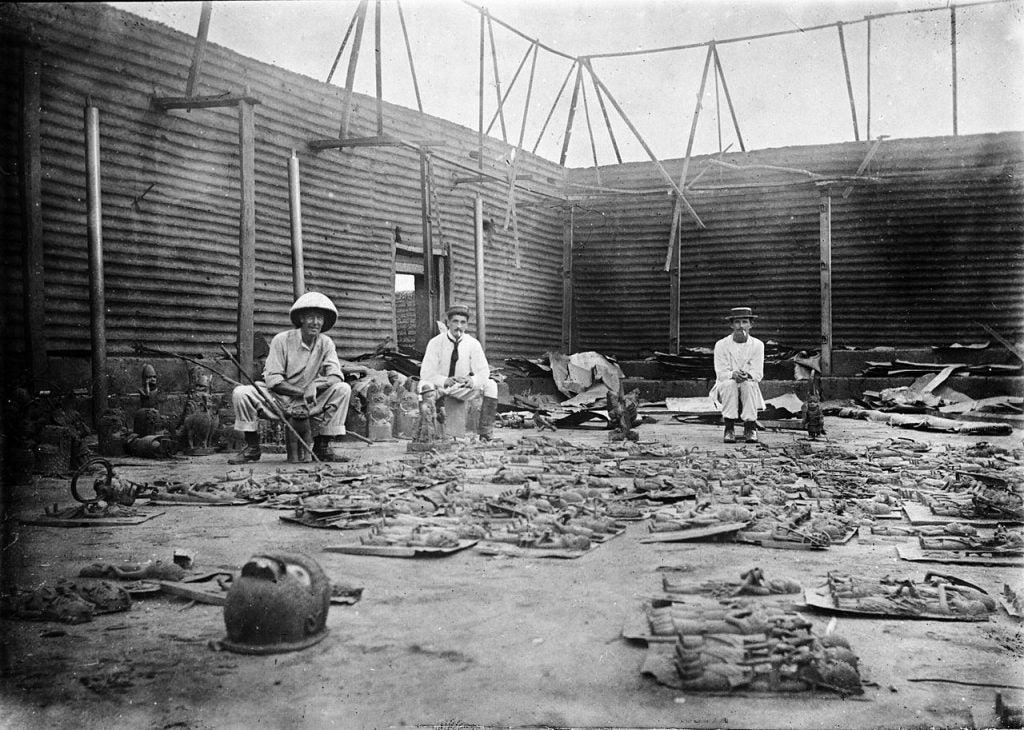

is the only African polity outside of North Africa, Nubia, and Ethiopia with 500 years’ worth of extant court art. This is due both to the materials palace artists most commonly used–brass and ivory–and the fact that Benin never endured a successful invasion until the British conquest in 1897. This began with an ill-advised effort by Britain to secure exclusive trading rights with Benin. A signed treaty to that effect–poorly understood and undesired by the Edo officials involved–did not have the desired effect. An ambitious British colonial officer decided to take advantage of his superior’s holiday and advance toward Benin City in order to argue for royal adherence to the treaty. He was warned to delay his trip, since he had timed it during a festival period when foreigners were excluded from the city. Ignoring this advice, he and a few Europeans marched ahead, accompanied by a large contingent of African carriers. Some Benin chiefs, indignant at his disrespect toward their monarch, intercepted the officer and his party, killing most of them. In retaliation, the British mobilized the Royal Navy, invaded the kingdom, and took over the capital. Thousands of objects from the palace, shrines, and other structures were stripped and shipped to London for auction (Fig. 886), ending up in private and public collections around the world. After a trial that saw the involved chiefs hanged and the monarch exonerated, they nonetheless exiled the Oba of Benin for the remainder of his life. In his absence, they razed parts of the palace grounds for new roads, administrative buildings, and living quarters, and set up their colonial government. In 1914, the exiled Oba’s son was allowed to take the throne as Oba Eweka. He rebuilt the palace–albeit on a smaller site–and the hereditary royal guilds began to cast brass and carve ivory and wood once more to decorate the palace and ornament the bodies of the monarch, his chiefs, and other aristocrats.

The Palace, its Altars and Royal Ancestral Shrines

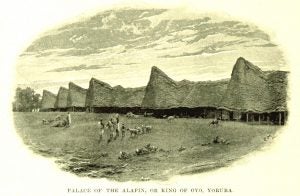

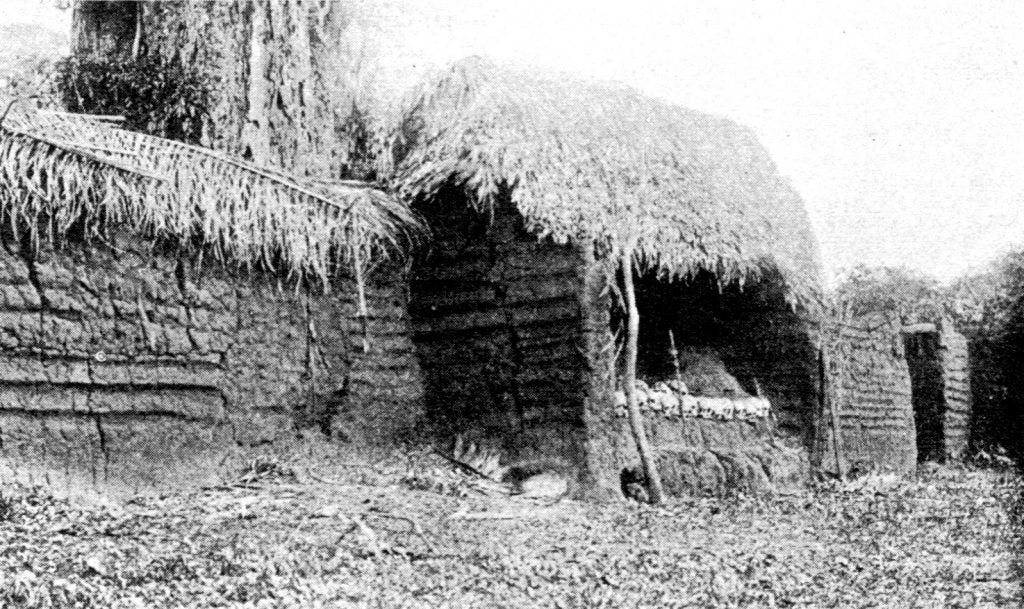

The current dynasty, which has been on the throne since about the late 13th or early 14th century, replaced an older dynasty that seems to have ruled since the 11th century. The newcomers built their palace on the cemetery of the indigenous rulers, laying claim to the land through its ancestors; this rite, however, was reenacted with each ruler “buying” the land from the representative of its autochthones. While this original earthen palace is long gone, we know it followed a building pattern that still exists: a walled royal compound consisting of multiple buildings constructed around open courtyards, their thatched roofs overhanging a walkway around the rooms themselves. By the 15th century, each monarch customarily built a new residential courtyard and reception hall when they came to the throne. They were eventually buried in their residential courtyard, with a royal ancestral altar constructed over the site. Annual ceremonies honoring past rulers took place in succession, each occurring in the courtyard of the Oba being celebrated.

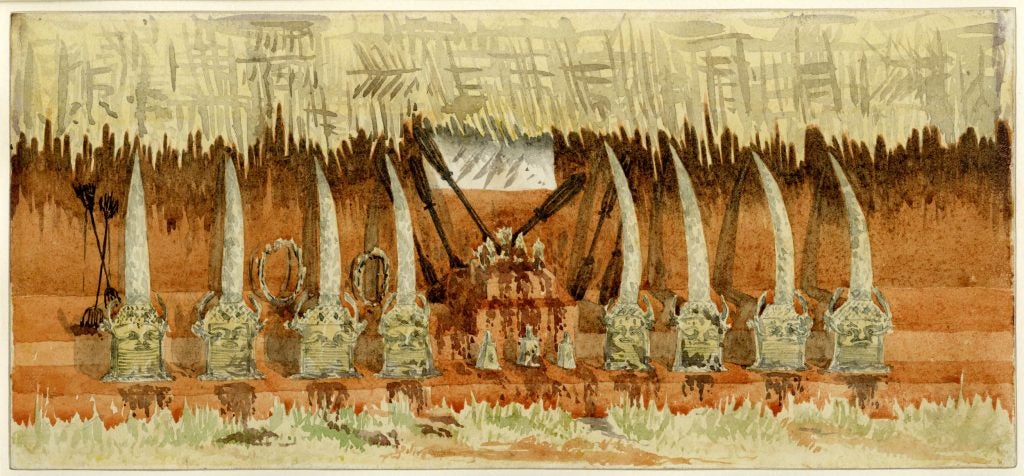

In the 16th century, Oba Esigie erected his own royal quarters, and their appearance was partially recorded by a royal brasscaster (Fig. 887). Though the use of hieratic scale emphasized the court attendants more than the building, we still have a sense of the structure and its galleries. The latter were supported by wooden pillars, four of which appear in the plaque. Each post originally had four brass plaques nailed to each side of its surface. The partially-broken plaque also refers to

several other key palace features. One was the existence of non-functional towers that are reminiscent of those marking major entrances of Yoruba palaces (Fig. 888). Another was the use of nailed wooden shakes, rather than thatch, for the roofing, a technique foreign to West Africa, and a third was the attachment of a snake and a bird (now missing) to the side and top of the tower. Like successive rulers, Oba Esigie used this prominent structure to project his wealth and innovative tastes.

Seventeenth-century palace visitors commented on the vastness of the palace. The Dutch publisher Olfert Dapper compiled information by an anonymous mid-17th century Dutch East India Company trader who had been resident in the area. He described the palace complex:

“The King’s court is square and stands on the right side of the town when you enter the gate [which leads] from Gotton [Ughoton, the river port where European ships docked]. It is easily as big as the town of Haarlem and enclosed by a wall of its own, similar to the town wall. It is divided into many fine palaces, houses and rooms for courtiers, and it contains beautiful long square galleries [other contemporary authors mentioned three or four] about as big as the

exchange at Amsterdam, some bigger than others, resting on wooden pillars, covered from top to bottom with cast copper, on which deeds of war and battle scenes are carved [actually cast]. These are kept very clean. Most of the palaces and royal houses in the court are covered with palm-leaves instead of shingles, and each is adorned with a turret tapering to a point [tapered, but actually flat-topped], upon which are skillfully wrought copper birds, very life-like, spreading their wings.”

Subsequent centuries showed continued innovations and changes. An 18th-century heavy brass box demonstrates that the shingled roof still protected the roof of some parts of the palace and snakes and birds still topped towers (Fig. 889). Despite fires that occasionally destroyed sections of the palace, particularly during an early 19th-century royal power struggle, by the late 19th century the palace continued to be a huge complex, with Oba Ovaramwen introducing the novelty of corrugated metal roofing, as well as imported inset mirrors in his own quarters. Retained, however, was the centuries-old tradition of horizontally-grooved walls, a palace tradition that was shared with honored chiefs (Fig. 890).

When the palace was rebuilt on a smaller scale in 1914/15, its earthen structure lacked towers but was mostly thatched by leaves used only for the palace. Unfortunately, a fire destroyed the structure and, when it was rebuilt in 1922, it was completely roofed by metal.

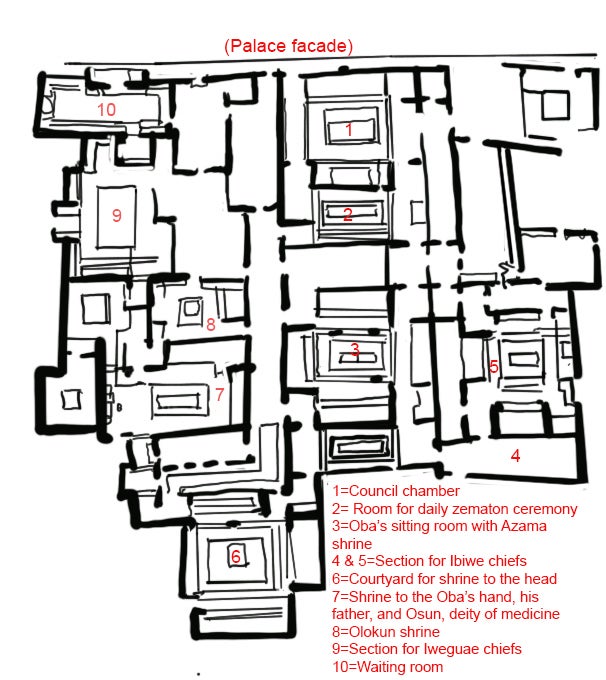

Subsequent 20th-century additions included some cement structures, air conditioning, and a billiards room. The interior includes sections dedicated to each of the palace’s three chiefly societies (and off-limits to non-members), as well as the harem and private living quarters. Its warren-like structure allows privacy and reflects organic growth over time (Fig. 891). The palace’s latest incarnation occurred in 2016 with the ascent of Oba Ewuare II to the throne. This Rutgers-educated former ambassador to Angola, Sweden, and Italy paved the palace forecourt, created a new facade, and had his own reception court and living quarters constructed as a two-story mansion (Fig. 892). A new main entry in a similar style, with the horizontal grooves referencing traditional royal and aristocratic architectural privilege, replaced a simpler gate (Fig. 893). Nonetheless, earthen sections of the building were not razed–they are simply not visible to the casual visitor.

As the limited floorplan above of an earlier layout indicates in part, the main palace includes numerous shrines to the deities of the waters and wealth (Olokun), medicine (Osun), iron and war (Ogun), the national deities (Uwen and Ora), the guardian of the Oba’s children (Azama), and others, including the monarch’s head and right arm. Additional shrines are found on the royal compound’s grounds, while other royal shrines are visible elsewhere in the city and throughout the kingdom. While photographs of more recent interior palace shrines to deities have not been published, images of older shrines are known–if imperfectly identified (Figs. 894 and 895). The reason for the latter is due in part to poor collection of information by the British colonists, and in part to a continuing diminution of traditional worship practices. The High God

Osanobua is the subject of many exclamations of shock or surprise. His major shrine was constructed in a basilica-like form in the 20th century on the site of what is believed to be a late 15th/early 16th-century Catholic church (Fig. 896). Numerous state and private shrines to Olokun, deity of the sea and wealth, still exist, as do private shrines to Eziza, the whirlwind, or Ogun, god of iron, technology, and war. However, some of Benin’s former major deities, such as Ogiuwu, god of death, and Obiemwen, goddess of fertility and farming, no longer have public shrines in Benin City. Catholic, Protestant, and Pentecostal churches abound, as do mosques. A Hare Krishna temple can be found in Benin as well.

Within the palace, the royal ancestral altars are key sites of veneration. Originally built individually in the residential courtyards of the various monarchs, they were reconceived in the early 20th century by Oba Eweka II. The 1897 destruction of the palace, subsequent parceling of its property, and the 17-year gap in occupation meant that some former altar sites now stood outside palace walls. His solution

was to build a large freestanding courtyard in the forecourt. Within it, most monarchs were honored by a single altar, while the altars of Obas Adolo and Ovaranmwen were erected independently on a gallery. Since then, they have been joined by those of Obas Eweka II, Akenzua II, and Erediauwa (Fig. 897). This gallery acts as the dais during many major ceremonies, and the seated Oba thus visibly and metaphorically has the backing of his royal ancestors.

Because the British had ripped the former altars of their treasures, the hereditary carving

and casting guilds had to create new altar decorations. Although brass and ivory objects are their best-known aspects, the only essential element for all altars–royal and commoner alike–are the ukhurhe wooden and occasionally brass staffs that lean from the earthen altar against the wall (Fig. 898). Ukhurhe are carved in imitation of the segmented form of a particular shrub’s branches, and represent the segments of a continuing lineage. When an Edo man “plants” (buries) his father, an ukhurhe must be placed on his ancestral altar. Royal ukhurhe usually end in a clenched hand or a hand clutching a mudfish; elephants and other finials sometimes top them. Chiefs and citizens use ukhurhe topped with a human head. Deities’ shrines also bear the staffs, but they are usually thicker with human figures interrupting the shaft. All ukhurhe are actually rattles; each includes a chamber with a trapped rattle. When holding and praying with the staff, it can be stamped on the ground or shaken to attract the attention of ancestors and deities.

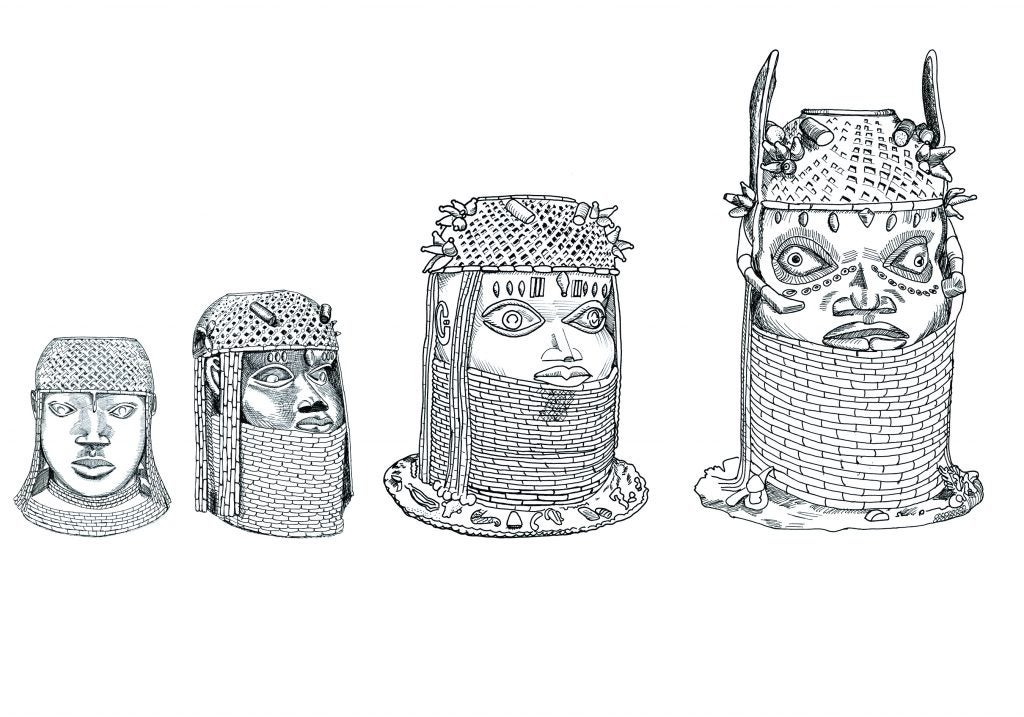

Shrine furniture includes brass heads of monarchs. These were placed in pairs or sets of pairs on and beside the altars (Fig. 899) and are not intended to be portraits of the deceased. They are emblematic rather than individualized, with an emphasis on the high status conferred by the beaded collar and crown, and on the powerful stare conveyed by iron-inset irises–the latter would have been intensified by their darkness contrasting with the surrounding brass.

Over the centuries, these heads became thicker, larger, more numerous, and progressively more abstract, their anatomy devolving as their eyes became increasingly stylized and huge (Fig. 900). Their stylistic progression remains fairly consistent within a given period (Fig. 901). The earliest examples from the 16th century have a sense of cheekbones and eye sockets, although there are abrupt transitions at the flattened bottom of the nose or the indentation on the upper lip. Their beaded collars are lower and rounded, and their crowns are made from beaded netting, with long hanging strands. By the 17th century, their beaded odigba collars (worn by the Oba and some chiefs) tightened and covered the chin, the crowns bearing sewn-on ornamentation of single beads and rosettes, with both beaded strands and braids hanging to each side. The face starts to keel, angling outwards from the eyes, and the former male scarification of three keloids over each brow is indicated. During the 18th century, the exaggeration of both eyes and keeling continue, and a circular extension creates a base bearing relief decorations of sacrifices. The 19th century saw the

addition of “feathers,” vertical crown extensions that flank the temples and curve forward. Many examples include two beaded strands that curve forward in front of the eyes. In the early 20th century, the revived guilds generally followed 19th-century structure and style, but the foreheads lengthened and the faces flattened, the ears becoming more circular. One late 20th-century head abruptly shifted to a naturalistic representation (Fig. 902).

Heads of the 18th and 19th century supported carved ivory tusks; some 17th-century examples may have similarly done so, but 16th-century heads probably are too thin and light to have done so, unless the tusks were very small. Surviving tusks are from the 18th and 19th century; palace fires seem to have destroyed some earlier ivories, and burn marks are evident on some extent pieces. Ivory was a royal monopoly, and added further status to the object. The tusk probably refers to the vertical extensions (oro) on some of the crowns, a feature shared by some priest-chiefs’ headgear. All call attention to the head itself, the most critical part of the body. Seat of many senses, it guides the body and houses destiny. The tusks’ low-relief imagery shows stacked registers (Fig. 903). Figures of humans are all vertically-oriented, as are many of the animals. Unlike most Benin art forms, tusks often feature both women and men–although the women in all media were restricted to depictions of the Oba’s mother (Iyoba) and her attendants. The tusks’ meaning can be deciphered by their references to specific rulers, both in their human form and as fish-legged representations of Olokun, deity of the sea and counterpart of the monarch (Fig. 904).

Before the British stripped the ancestral altars, the variety of additional decorative sculpture was considerable, and included representations of courtiers who woke the Oba, hornblowers who accompanied him during processions, equestrian figures and Portuguese with guns and other weapons. Although these had their origin in the 16th century, later casters copied them for subsequent graves–their style, however, reflects that favored by contemporaneous heads (Fig. 905).

While these sculptures were discontinued in the 20th-century revival, the idea of a central figurative group on a rectangular base–the aseberia, which seems to have been an 18th-century innovation–has continued. Unlike the heads, these brass tableaux are individualized by emblems, though not by facial features. One aseberia, for example (Fig. 906), depicts Oba Ewuakpe, a late 17th-century monarch who holds a spiritually-charged pestle in his right hand. Meant to negate curses, it is his identifier on both this altarpiece and on carved ivory tusks (Fig. 904). Ewuakpe suffered the rebellion of his subjects and was driven from the palace, forced to work for a living. It was only though through his literally self-sacrificing wife that he was able to regain the throne. Here he is shown with few royal accoutrements–he wears a hat, rather than the beaded crown, and his high color, anklets, and other necklaces are far more limited than the usual kingly regalia. He is supported by two

attendants whose facial marks and lean bodies suggest they are foreign slaves, rather than loyal courtiers. Nonetheless, his return to the throne marked an upswing in monarchical control, and his successor commissioned this work to honor Oba Ewuakpe, alluding to both his downfall and recovery.

Monarchs are not the only ones who are honored with metal objects on their ancestral altars. Beginning in the 16th century, rulers created ancestral altars to their mothers, as well as their fathers. The Iyoba, or queen mother, receives her title a few years after her son took the throne. She is the only female chief, and technically belongs to the group of chiefs who are self-made men and made up the bulk of generals in past centuries–but she does not attend their meetings. The Iyoba has her own palace, chiefs, and attendants but traditions state she cannot see her son after her accession. At the time of her death, she is celebrated with a dance performed only for the Oba, and she–like the monarch–is represented by a funerary effigy (Fig. 907). Altars are set up in her honor at her own palace and the Oba’s palace. Pairs of brass heads depicted her with a “parrot’s beak” hairstyle, its shape mimicking that of the hats her chiefly group wears; a netted bead

covering holds it in place. Like the royal ancestral heads, only later examples ever supported ivory tusks, and the images grew more and more stylized over time (Fig. 908). Fewer examples exist.

Aseberia (Fig. 909) were also made for Queen Mothers, as were brass roosters (Fig. 910). The latter were among sacrifices made to male ancestors, on the altars of Iyobas because they became, in a way, honorary men. Ukhurhe also stood on their altars, as did ivory figures of female attendants.

The altars of commoners–with the exception of the brasscasters, who can own terracotta heads–bear only carved wooden ukhurhe, but those of chiefs are more distinguished. In the past, wooden representations of ram or antelope heads decorated chiefly altars, the animal displaying the valued male qualities of aggression and tenacity (Fig. 911). An 18th-century French observer described the tomb of a “big man”: “On the top are placed beautiful elephant tusks each weighing forty to fifty pounds, well carved with images of lizards and snakes. These tusks are set on crudely carved wooden heads of rams or bullocks.”

In the first half of the 19th century, chiefs received permission to decorate their altars with wooden representations of chiefs’ heads (Fig. 912). These show chiefs wearing odigba beaded colors and coral headbands with a vulturine eagle feather. Their tiered hair shows, and the three archaic scarifications men once wore occur over the brow, inlaid (like the pupils) with a darker wood. Those chiefs of high status were granted the privilege to add sheet brass strips, evidence of strict controls over this prestige material.

Although some powerful chiefs added ivory tusks to their altars in the late 18th century, this is rare today. Likewise, only a limited number of chiefs are allowed to create altars for their mothers. These are decorated with ukhurhe–shorter than those used for male ancestors–wooden hens (Fig. 913), and wooden sculptures of female attendants.

One type of brass head has been confused with those found on royal altars (Fig. 914). These do not, however, represent Benin royal ancestors, despite the use of valuable metal and the color of beads worn at the neck. They are not crowned, and the Oba is never seen bare-headed. Instead, they are permanent depictions of high-ranking defeated enemies, whose actual heads were taken in battle. They bear four, rather than three, keloid scarifications over each brow, the mark accorded a Benin female or a foreign man. A photo taken in the late 19th century shows two such heads hanging from a medicine staff in the palace (Fig. 915); similar staffs were carried into battle. While some of these heads date from the 16th century, they continued to be made through at least the 18th century, reminders of glorious victories.

Prestige Materials: Coral, Ivory, Brass, and Red Ododo Cloth

The red and pink coral beads that Oba Ewuakpe lost and regained are one of Benin’s most striking dress elements. First imported by the Portuguese in the late 15th century, they were eagerly purchased, perhaps because reddish-brown stone beads made from jasper or chalcedony already served as marks of high status, and coral’s brighter color and status as a luxury import made them equally desirable. Red is a key color in Benin symbolism, as is white. White is associated with peace, prosperity, coolness–white kaolin “chalk” paints parts of the palace interior, and anoints people during ceremonies as a sign of luck, while ivory is also white. Red is associated with blood, war, power, and things threatening. The Edo categorize colors as white, black, cool (blue, green, violet), or hot (red, yellow, orange). Brass (when kept polished) is thus red, as are coral beads.

No one wears or owns more coral than the Oba, whether marine coral or stone “coral.” His regalia (Fig. 916) includes not only a selection of crowns, bracelets, anklets, necklaces, the high beaded collar called odigba, and crossed chest bands, but also coral-ornamented shoes, flywhisks, and netted beaded wrappers and shirts (Figs. 917 and 918). Because these items are heavy, most are not worn on a daily basis. A cloth cap can serve as crown, and netted garments are reserved for festival appearances. A coral circlet (ikele), coral bracelets and anklets are, however, standard.

Chiefs are awarded an ikele when they take a title, and also own an assortment of bracelets, anklets and necklaces, as well as a beaded headband. The high odigba collar, however, or one of half height, is awarded to only certain titleholders. The Oba’s wives and children own ikele and coral ornaments, and chiefs’ wives and children are allowed to wear coral necklaces and bracelets. The royal wives, chiefs’ wives, and brides also wear coral ornaments in their hair when they wear a special ceremonial hairstyle that features a bee-hive arrangement with braided arches (Fig. 919).

Coral beads have amulet-like protective powers, as well as prestige. Those belonging to the royal family and the chiefs are recharged during a palace festival by the sacrifice of a cow. In centuries past, a slave was sacrificed over them, a rare occurrence that spoke to their significance and power.

Ivory is another precious material that is normally restricted to the Oba. It also is a medicine–literally. The carvers’ guild keeps all ivory shavings, for they are critical ingredients in certain mystical preparations. Because the color white represents peace and joy to the Edo, ivory has assumed those associations. For centuries, the Oba has worn ivory armlets at the wrist (Fig. 920), as well as pendants at the waist.

Among the latter are some of the most prized art objects from Benin: a 16th-century pair of waist pendants that represent Idia, the mother of Oba Esigie (Fig. 921). Their matching grain confirms they were made from the same tusk, and the same artist carved them. Though a pair, they are not absolutely identical, as indicated by the row of heads at the top and the flat area below the beaded collar. Idia was recognized as a witch, and Esigie honored her in multiple ways since she used her supernatural powers in multiple ways to secure and hold the throne for him. In these two pendants, she is idealized and shown in her prime. Accorded the privileges of a high chief, she wears a collar of beads at the neck, but the artist could not replicate the special hairstyle she wore on contemporaneous bronzes (Fig. 908) because the thinness of the ivory section would have prevented a forward projection, and it would have proved an irritant to the wearer. Instead, her hair is dressed in short, upright braids, each topped with a bead (Fig. 922), and, at the front, a mass of drilled projections, now worn down. An arching row of either Portuguese heads or Portuguese heads alternating with mudfish lays in a transverse crest at the top of her head. Their prominence speaks to the assistance a handful of armed Portuguese gave to Esigie in several wars early in his reign. Their association with the mudfish–a liminal animal associated with the deity of the seas, rivers, and wealth–on one of the pendants is one of many pieces of evidence that they, too, were considered Olokun’s creatures because of their sea travel and exotic luxury goods. Small pieces of brass inlay various details of the work, but originally iron was inserted in the irises, around the eyes, and in two strips between the brows, as also occurs on brass heads of both the Oba and his mother. The two vertical lines are a stylized frown; combined with the other iron, it demonstrated the power inherent in the Iyoba’s gaze because of her supernatural abilities. The four worn relief vertical marks over the brow mark the face as female.

These were not the only two face pendants that represented Idia. As breakage and loss occurred, they were replaced by other versions. Some had iron-inlaid “frowns,” but none had the delicate brass inlays of these earlier versions. Even today, stylized faces are part of the royal ceremonial regalia (Fig. 921). Past Obas valued even the damaged versions, though he no longer wore them. When the British invaded, they found them in a wooden chest inside the Oba’s bedroom.

Brass has always been a valuable material, controlled by the monarch. Its reflectivity and–according to Edo terminology–reddishness have accorded it power, and its rarity before direct contact with Europe established it as a luxury metal. Obas have used it

not only for royal altarpieces, but for architectural decorations, like the plaques that once

decorated Oba Esigie’s reception hall, or the brass snakes on palace towers, or objects that decorated the royal interiors, or ceremonial containers (Fig. 922).

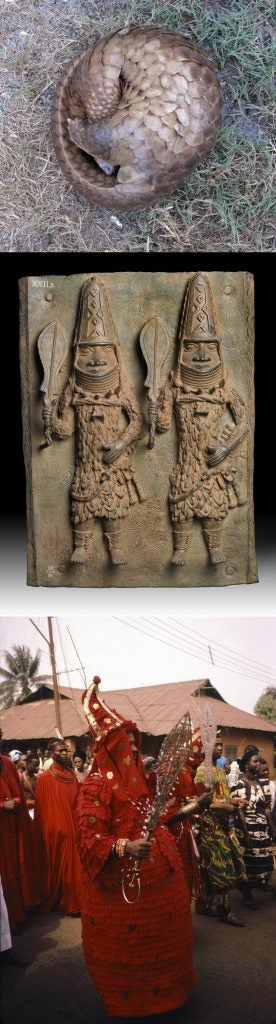

The plaques–over 800 were once nailed to the wooden posts that supported the courtyard roof of his reception hall–demonstrated the Oba’s great wealth and taste to any visitor. These rectangular plaques featured numerous subjects: primarily courtiers (Fig. 923), relatively few images of the Oba himself (Fig. 938), numerous animals–especially mudfish, snakes, crocodiles, leopards, and birds, the Portuguese, and a few inanimate objects. Most depictions of people are formal, frontal, and iconic; when multiple figures appear, their faces are shown identically, and hieratic scale indicates their relative importance (Fig. 923). Less-dignified individuals were sometimes experimentally placed in a three-quarter, turned pose, a treatment most often accorded to the Portuguese, whose foreign printed sources probably served as models for the

position. Other unusual treatments that seem to have a foreign impetus are references to foliage (Fig. 924) and even to action, which occurs in a handful of battle scenes (Fig. 925).

While courtier depictions ranged from the monarch and his noblemen to guild members (Fig. 926) and even low-ranking page boys, no women appear on the plaques. The plaques include highly unusual examples of still life depictions in African art–fans, gongs, aspects of ceremonial attire, a bag, a leopard pelt–but they are formally presented, without environmental

references (Fig. 927).

Brass had many personal uses for the aristocracy. Monarchs have also consistently granted many chiefs the privilege of wearing brass armlets (Fig. 928) and hip pendants, as well as other accessories, all marks of royal favor. Chiefs’ wives and women with minor palace titles stick thin brass “feather” ornaments into their okuku beehive-style coiffures.

Most Benin brasses in museum collections have darkened through oxidation. In Benin, however, most are polished at least annually with lime juice and sand in order to maintain their sheen.

Ododo is a red cloth associated with the Oba, very high-ranking chiefs, and certain masquerades. It was imported by the Portuguese, its prestige associations cemented by its priciness, sumptuary laws, and its red color. While the original ododo was made of felted red wool, the textile’s near unavailability has led to substitutions of other varieties of red cloth.

Related Benin legends talk about the introduction of coral beads, brass vessels, and ododo to the kingdom. Some say they were wrested from the palace of Olokun, god of the sea and wealth, by Oba Ewuare in the 15th century, while others claim his right-hand man Okhuaihe was their procurer. This likely stemmed from a more prosaic occurrence. The Portuguese had landed at the coast and initially made contact with the Itsekiri people to Benin’s south. Some foreign trade goods found their way to the Benin court, and the Oba probably sent one of his courtiers south to discover the source and direct the Europeans to Benin’s port of Ughoton.

High-ranking chiefs often own special gowns used today only for palace ceremonies. Made of ododo, they have a long history; some of Esigie’s plaques show war chiefs wearing them for a festival, holding their ceremonial eben dancing swords. Made from overlapping scalloped strips, their surface is petal- or feather-like, but they actually represent animal scales–the scales of the pangolin, a mammalian anteater who curls itself into a ball when threatened (Fig. 929). When thus protected, as an Edo proverb states, “Even the leopard can crack its teeth on the pangolin.” As such, this garment, known as “pangolin skin,” reminds the monarch and spectators that chieftaincy at their level is not to be taken lightly. In their progress through chiefly ranks, they had to combine political cunning with supernatural medicine for self-protection. If the Oba tries to dispose of them, he may find it difficult or impossible.

Precious materials–coral, brass, ivory, and ododo–are frequently on display at palace ceremonies, as can be seen in the video below.

Symbols of Power

Like many African societies, Benin’s imagery is a rich reflection of metaphors drawn from proverbs, divination, and other oral references. The pangolin is only one example; Benin art is full of significant depictions that have meanings beyond the obvious. The chiefly armlet in Fig. 928, for example, includes representations of both mudfish and Portuguese heads. Both refer to the watery world of Olokun, lord of riches, because of their associations with water, and the Oba is considered Olokun’s counterpart on earth. One of his thrones shows interlocked mudfish (Fig. 930), a reference both to Olokun and his own liminality.

The Oba himself is identified not only with Olokun, but with the leopard, who shares the Oba’s beauty and fierceness. The Edo view the feline as the king of the forest, or bush; one of the Oba’s praise names is “leopard of the home.” So strong is this identification that there are many leopard euphemisms that refer to the monarch:

“the leopard is in the shelter’ (the Oba is sleeping) or “the leopard is sick in the bush” (the Oba is very ill). Royal guilds for capturing, taming, and sacrificing leopards existed in the past, and depictions of the feline could be found in many secular forms. The palace contained both sculptures of leopards and leopard vessels (Fig. 931). They appeared on numerous plaques with and without bells at the neck, the marker of the domesticated cat. On both castings (Fig. 932) and carvings, a leopard attacking an antelope stood for the Oba’s destruction of his enemies. Only the monarch had the right to take life, but he conferred this right to his military officers, frequently with visual markers. Some wore actual leopard pelts on their chests, while others bore cloth tunics embroidered so their whiskers and eyes made the feline correspondence evident (Fig. 933). Both the Oba and certain military chiefs wore leopard head pendants at the waist or hip, though the mediums differed (Fig. 934).

Similar pendants representing crocodile heads were also worn, and multiple representations of the reptile were found on courtyard plaques (Fig. 935) as well. The crocodile is viewed as Olokun’s military enforcer, but a proverb also refers to the Oba’s tenacity: “When a crocodile grips its prey, it doesn’t let go.”

Snakes frequently appear in Benin art as well: on the palace turrets, on plaques, emerging from the nostrils of ritual specialists on brass heads, pendants, and vessels, and on other objects. Most Benin animal portrayals are not species-specific, so it is often difficult to know which variety of snake is depicted. Poisonous snakes are often associated with

ritual specialists and their medicinal powers, said to extend to their breath. The puff adder is allied to riches, while the non-poisonous python–since it is at home in the water as well as the land–is part of the world of Olokun. Two royal thrones are supported by snakes that are presumed to be pythons (Fig. 936), their surfaces covered with land and water animals. While the seat of the earlier example bears two crocodiles

and two mudfish, as well as patterns, the later version is covered with blacksmith’s tools, simian faces, an elephant with trunk-hand, and two pythons who have swallowed a human being each, a fist protruding from each mouth. While the meaning of some of the imagery remains obscure, each includes references to supernatural medicines and to power. In form, they do not resemble the modern throne, but they have a wooden analogue in the shape of stools still owned by priests and chiefs acting in a priestly capacity (Fig. 937). These stools are also supported by two intertwining pythons, and frogs–a reference to medicine–frequently appear in relief on their bases. It’s possible that the thrones were used by the Oba during altar activities, rather than at public festivities.

Mudfish frequently appear on Benin art. Plaques show them–as they do other fish–swimming in the water, as well as coiled and skewered, the way they’re smoked for sale and consumption. But Benin has many varieties of mudfish. While all are related to the water, and all constitute liminal animals, only one type carries an electrical charge. This electrical mudfish is associated with the Oba, because he is said to have the power to shock and awe those in his presence, just as the mudfish physically shocks individuals. Frequently the Oba is depicted with mudfish legs, a feature that aligns him with Olokun, ruler of the waters, his divine counterpart (Fig. 938). This is a glorifying image; here, the Oba shows his mastery of his bush counterpart, the leopard. Carved tusks and other ivories frequently show him similarly holding crocodiles. However, these images hold two messages: one stresses the divine nature of the ruler, the other reminds him of a cautionary tale.

In the early 15th century, Oba Ohen was on the throne. He chafed at the control the chiefs had over him, even restricting his movement outside the palace by confining him with a constant entourage. At night, he snuck out of the house and even went outside the city walls. While the Oba can marry just about any woman he chooses, he is forbidden to marry his relations and the offspring of a few other families. A young woman from one of these families caught his eye, and he began to court her surreptitiously. One of his chiefs was suspicious of his nocturnal movements and followed him. When he saw he crossed a bridge, he confronted him the next day, but the monarch claimed he had stayed at home all night. The chief collected a slow-acting mystical poison and placed it under the bridge, cursing it: “This shall harm no one but the royal one who denied; if he crosses the bridge, may it strike him.” He also vowed to discover what the monarch was up to. The Oba almost was caught by a search party, but was warned by a young palace page who was standing watch outside the young woman’s house. He quickly dressed the two of them in a cloth and stuck some feathers in it, dancing out of the house with the page, and bringing her into the harem in the guise of a masquerade (see video below).

The Oba didn’t need to leave the palace again, but the chief continued to watch him carefully. One day the Oba felt a numbness in his lower legs. They grew rubbery, and he could no longer walk. One cannot sit on the throne with a severe physical disability, and he was concerned for his survival. He convinced his pages he was transforming into Olokun himself and instructed them to keep his secret. He had always waited for his chiefs to enter his meeting room before coming in himself, but now he would already be seated before the first chief appeared, and wait until they departed before leaving for his private chambers. The poisoner thought his medicine had worked but wanted to be sure. He hid when the chiefs were dismissed and saw the pages helping the Oba move. Oba Ohen caught him spying, however, and executed him. The chiefs were suspicious since their colleague had never left the palace, but the monarch denied he knew anything about the chief’s fate. Rebellion was in the air. The chiefs dug a pit before the throne and covered it with a handsome mat. As the Oba approached it on a meeting day, the mat gave way and he was trapped. The chiefs entered the room and stoned him to death with rocks painted white to resemble lumps of chalk. Because of the awe the Oba inspires, he is said to never drink or eat–except for chalk, the substance of joy and purity. In this way, regicide had an innocuous yet cynical face–his chiefs were “feeding” him. Every year during a ceremony, high-ranking chiefs mime an inquiry for their missing chiefly leader, and the Oba then shrugs, as if to say, “I don’t know.” Through both ritual and imagery, the monarch is reminded that, great though he is, even he must pay for the consequences of his actions.

Masquerades and Ceremonies