Appendix C: Researching a Project–Introductory Level

Research problems can vary in scope and direction, depending on an instructor’s directives. Some require developing a thesis and building on evidence to reach a conclusion–others are purely informational summaries. If the desired output is a standard term paper, it needs an introduction and a conclusion, but other formats may demand greater brevity packed with information. This section will not address these critical issues. Instead, it is directed toward the actual research process–how to find the best sources dealing with African art that can answer your questions. For that, you need to at least narrow your subject enough to identify possibilities. Presumably, you are not trying to cover all the art from one area or everything that falls under a specific theme. The ideal sources are those that are as specific as possible; you would not normally start with general books on African art.

Other Sources’ Bibliographies

If you’re at a loss where to start, identify at least one good book or article related to your topic. If something in a “Further Readings” section of this textbook is associated with your project, find that source and go straight to the bibliography in the back of the book or at the end of the chapter. This will get you started. The more recent the source is, the more up-to-date its bibliography is likely to be. While you won’t want to stop with this process, it’s an easy way to avoid getting lost in general materials that will be of little use. Perhaps “Further Readings” provides no lead, or you have found little in the bibliographies you’ve seen. What next?

Library Catalogues, Keyword Searches, and Shelf-Reading

Your library will have an online catalogue, but you need to know that it will only include books and the titles of journals–not the titles of articles. Books can be ideal resources, since they will lead you to other sources. Don’t assume that books that are older are useless–art history is not biology, and many earlier sources may provide valuable information that no one has updated, or they may examine facets of art and culture that have changed, or they may examine exactly what you’re looking for, rather than what a more recent researcher finds interesting. When you’re looking in a card catalogue, try for the keyword search, unless you already know the name of the book or author you’re seeking. You may have to vary your keywords in order to be successful. Perhaps you’re trying to find information on Hausa palaces. By all means, try searching for Hausa palaces. However, if that’s not successful, try Hausa architecture or Hausa buildings. Nothing? Try Hausa art or consider the country, rather than the ethnicity–perhaps Nigerian architecture would work. Nothing? Only then should you check “African architecture.” As you learn more about your topic, your keyword searches may expand.

Once you’ve found some books, locate them on the shelf and stop. There may be other, related sources that are valuable–and they may be next to the book you sought. Shelf-reading just involves looking at the books nearby, for books are shelved logically, and like subjects are often grouped. While the speed and ease of online articles may be comfortable, they are not always your most comprehensive sources. Authors put years of research into books, and often coalesce the findings of their articles in these longer works. They are also frequently indexed, unlike articles, which can make it easier to find the sections you need.

Databases

Databases index sources, but you have to understand what any given database covers–is it for books, for articles, or for both? While some databases are found on your library’s website, others are independent of it. For African art, the two most valuable databases for identifying sources are independent sites that include both books and articles: the Smithsonian Institution’s library catalogue (siris.si.edu) and Worldcat.org. These are both excellent sources; although they overlap considerably, they are not identical. Use keyword searches for both (see above) unless you already know a relevant author’s name. Try search terms relating to an object type, an artist’s name, an ethnic group’s name, a site’s name, and, last of all, a country or region’s name. EXAMINE the searches—ignore one-page articles, since they’re probably just illustrations without text. If you notice your search has produced 15 pages of hits, don’t stop looking after the first two pages–actually spend time and examine the titles of all of the hits, for they aren’t arranged in order of importance or date. You need to know what’s available. Once you’ve found the most likely sources, note the publication info, because you can’t order from either source–these databases just identify sources. Both of these databases allow you to select likely possibilities and email your choices to yourself.

If your relevant sources are books, check your library’s catalogue to see if they own them. If your university library doesn’t own them, but you live in a large metropolitan area, check the card catalogues for your public library system and other nearby university libraries. Some states or universities are part of a consortium that enables you to order books from elsewhere in the region and have them delivered to your school; Ohio, for example, has Ohiolink. Order these sources early, for as the semester progresses, more and more students will be ordering books and the system slows down. In every state, you can use Interlibrary Loan. Your university library probably has a way to sign up for this free service on their website, as well as electronic forms to order materials.

If your relevant sources are articles, your library may have print copies of the journals, or be able to access them through electronic websites on your library website. The most valuable of these databases is JSTOR. Once you input your discovered titles or authors’ names into JSTOR’s search, you may have access to the actual, full article in pdf form. However, every library picks and chooses what journals are in their JSTOR subscription. You may have identified the perfect article, but its journal is not available in your library’s JSTOR or other databases. If that is the case, you can also order articles through Interlibrary Loan (see the paragraph immediately above). You will need all the publication information to place the order. Your library will discover which institution has a copy, and then forward you a pdf of the article once it becomes available. Even obscure journals can usually be located this way, but order early since this may take some time.

The Internet

For almost any project, Internet sources should be avoided absolutely. They are not necessarily written by experts–in fact, they usually aren’t–and they may be riddled with misinformation. The exceptions to this rule are limited–if your topic involves a living artist who has a personal website, that could be a legitimate resource, as could YouTube or other video recordings or posted interviews with the artist. While there’s nothing wrong with consulting a textbook, an encyclopedia, or Wikipedia to get a quick feel for your topic before beginning research, these are not sources to include in your bibliography.

Contextual Material

Since discussions of African art normally require contextual information that places a work or group of works within its society, your research may not be entirely based on art history sources. Useful resources might deal with the religion of the region you’re discussing, or the political structure, or the modes of burial or performance. Investigate supplemental material from anthropology, history, religion, and customs. Travelers’ accounts or colonial memoirs may provide useful quotations or other early information–your best guide to these may be the main sources you’ve found. An author might include a brief quote from an 18th-century book–that book might itself contain many more valuable passages.

How Many Sources?

Your instructor may mandate a minimum number of sources. If they don’t, or even if they do, the real answer is “as many as you need.” Some sources are extremely valuable, going into your topic in great detail. However, your research cannot be limited to one author, no matter how golden they appear. You won’t know whether they are actual experts or are just consolidating other peoples’ work until you see what other writers are producing. A work may initially appear worthless, but for three paragraphs of direct observation found nowhere. The longer and more specific your topic, the more sources you should investigate. It’s a rare topic that benefits from less than five sources; many require twenty or more.

Caveats and Suggestions

Watch out for the following:

- Make sure when you’re hunting for articles that you don’t mistake a book or catalogue review for the book or catalogue. No professor wants a review as a source rather than the book it’s referring to.

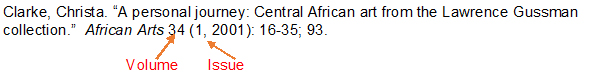

- Make sure you can recognize database sources. A book includes a city, publisher, and a year. A chapter in a book usually includes a chapter title in quotations, as well as a book title with editor, city, publisher, and year. An article can be distinguished from either because its title is in quotes, the journal’s name is present, and it has a volume, issue, year, and page numbers. Interlibrary Loan services require all of the above information in order to fill forms.

- This is a sample article reference:

4. Take a few moments to do some quick research on your author–your best sources for African art will be scholars who have spent time there and have credentials. Maybe they are African scholars with Ph.D. degrees, or foreigners who spent a significant amount of time researching in the continent and are university faculty. A person on a holiday with a blog who wandered into a ceremony is unlikely to know enough about it to provide useful analysis and accurate information. Your professor probably knows the major authors who work on your topic and have done their own research, as well as familiarizing themselves with those also associated with the topic. If you leave such authors out in favor of someone who aggregates information, you are unlikely to strike gold.