Chapter 1: Orientation to Africa and its Art

Chapter 1.2: Gender, Materials, Techniques in Traditional Art

THE PATH WITH ROOTS: TRADITIONAL AFRICAN ART

Traditional African art restricts the use of certain materials to a specific gender—in most cases. Because it’s a huge continent, many aspects aren’t absolute, but apply to most cultures outside of North Africa. An examination of materials and techniques will elucidate the least and most flexible aspects of artists and fixed gender.

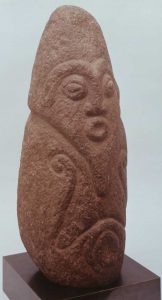

Carving: Wood, Ivory, Stone

Carving is a subtractive sculptural approach. Artists remove material when they carve. Worldwide, the most common carving materials have been wood (Fig. 13), stone, and ivory. South of the Sahara, stone is the least common of the three, but it stone carving does occur in a few regions. Because of its rarity, its use is worth noting; it has the most durability and longevity of the three materials. Ivory is a luxury material. Although it was readily available in many parts of Africa, its use was usually restricted to rulers, aristocrats, or those recognized for special achievement. Wood was the most common carving material, although it became rarer in arid regions.

Men exclusively carve wood, ivory, bone, and stone, all subtractive substances that require sections to be removed in order to create the desired form. They usually are also responsible for cutting down the tree that yields their material, usually with a prayer or small sacrifice to honor the spirit housed within.

Sometimes the chosen wood is mandated by the type of object. In general, lightweight woods are used for masquerades to lessen the dancer’s burden, while artists select denser, weightier specimens for figures meant to be termite-resistant. The traditional artist’s toolkit formerly consisted of a set of differently sized adzes and knives for finishing work. The adze (Fig. 14). chops into the wood and towards the artist, a motion not unlike that of the African farm hoe, whose shape it mimics. Artists work directly into the wood without preliminary drawings, blocking out the basic forms, then refining them. In nearly all cases, objects made from wood are monoxyl, that is, made from a single block of wood, rather than joined by glue, pegs, or nails.

Wooden sculptures are frequently painted. While traditional artists often employ manufactured paints today, colors made from botanical and mineral sources were standard in centuries past. Even when the wooden surface remains unpainted, handling and the application of oil and pigment may change the surface color; this also can occur with ivories. This result from handling isn’t produced by the artist, but by the owner, and is intentional. It is known as a patina, and can also develop from sacrificial materials poured on the artwork (Fig. 17). Neither worn paint nor insect damage constitutes a patina.

Scientists can approximate the age of both wood and ivory through the Carbon-14 dating or radiocarbon dating technique. This testing can only be used on substances that were once alive: bone, charcoal, wood, ivory, textiles made from cotton, wool, linen, silk, etc. The method checks the decay rate of carbon-14, a radioisotope, to determine age. While fairly effective for dating items from the distant past, it cannot easily distinguish an object made in 1700 from one carved in 1850; the plus or minus accuracy diminishes as one approaches the present. One exception, however, occurs. Items whose carbon-bearing material was alive after 20th-century nuclear testing and the explosion of fossil fuel use show a different profile, so these recent items have artificially higher radiocarbon levels. Stone objects, being inorganic, cannot be tested with radiocarbon dating, nor any other scientific method to date, although the age of the rock itself can be geologically determined.

Why is carving restricted to men? Most artists don’t articulate the reasons, attributing this to custom from time immemorial. However, the practice seems to stem from dual beliefs: women may become infertile if they work with objects used in sacred contexts and their bodies during menstruation have the power to neutralize the supernatural medicines that often activate masks or figures.

Metalworking

Metal arts are also restricted to male artists. Some artworks are forged; that is, metal is heated and then hammered into a given shape. Iron is most often treated in this way, and the method itself limits the complexity of shapes produced. Works created this way are usually simplified (Fig. 18)

Thin sheet metal, such as brass or copper, can be decorated by pressing designs into the surface (chasing), creating dots on the surface (stippling) or hammering designs outward from the back to create a relief (repoussé). These methods create an embossed effect (Fig. 19).

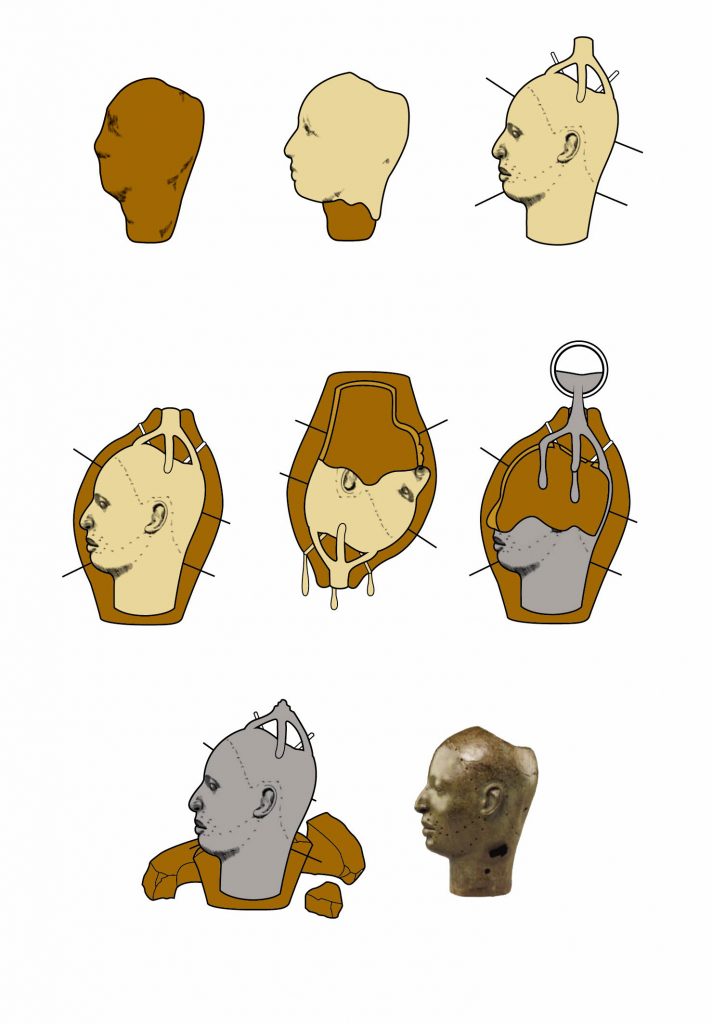

The use of molten metal poured into molds can produce more complex results. Some molds can be reused, resulting in solid metal objects such as coins (Fig. 20). Since a solid metal form and a hollow one look identical, a desire to conserve valuable metals led to a one-use mold technique meant to produce hollow sculpture: the lost wax casting technique, also known as cire-perdue.

To produce such a casting, the artist begins with a lump of clay, shaped loosely like the desired result. The artist covers that core with a thin layer of malleable beeswax and works details into the wax with a tool. Sometimes the wax is rolled between the palm to form wax “threads,” which can then be coiled or hatched, producing a raised texture. Sprues and vents are then attached to the wax. Both are wax cylinders; the sprue will eventually become the channel where liquefied metal enters the mold, while the vent provides an exit for any gases. The artist then applies a fine, semi-liquid layer of clay to the wax surface, making sure it fills all crevices. He then packs clay around the object, including all but the ends of the sprues and vents. This outer pack of clay is called the investment, and it is allowed to air dry. At this point, the object looks like a dry clay lump. Placed in a fire, it is positioned so that the liquefying wax will run out. The wax itself is what is “lost” in the process, although the artist usually collects the liquid run-off for reuse. The lump now has the following three layers: the clay core, a gap where the wax once was (including empty channels were the sprues and vents were), and the outer investment. Metal has been heated in a crucible and is poured into the sprue channels until all empty spaces are filled. The metal is left to cool, and the outer clay mold is cracked off. The sculptor then files down the metal sprue projections and cleans the surface. He may choose to remove the clay core or leave it in place (Fig. 21).

For most of Africa before the 20th century, brass and bronze—both copper-based or cuprous alloys—were the most

valuable metals, for these alloys depended on imported or long-distance trade components. Copper itself does not flow readily, so sculptors usually add other metals to form alloys for smoother castings: copper plus tin makes bronze (Fig. 22), while copper plus zinc makes brass. Gold was exploited in Senegal and what is now Ghana, as well as in parts of southern Africa, and can also be cast through cire-perdue. Relatively little silver occurs in Africa; its use in art (Fig. 23) typically derives from imported metal, particularly the European Maria Theresa thalers, first minted in the 18th century.

Metal itself cannot be scientifically dated, but if the clay core remains in a sculpture, that core’s firing date can be determined through thermoluminescence or TL-dating. This procedure ascertains when certain materials such as clay were heated, measuring the object’s radiation since firing. It permits more accuracy than carbon dating.

Terracotta Sculpture and Pottery

Working with clay is an additive approach to sculpture since forms are built by adding more and more clay and modeling the form with fingers and tools (Fig. 24). Modeling is a more forgiving art, because corrections can occur until the material hardens. Although unbaked clay can be molded into a variety of forms, heavy rain will turn an unprotected figure back to soil. In order for clay pots or sculpture to become permanent, they must be fired or “baked.” In Africa, this means they are placed in an outdoor pit after sun-drying, usually with a group of similar pieces. Light brush is positioned around the works, then firewood is stacked over the whole and set alight, burning throughout the night. After firing, works are referred to as terracotta pots or sculptures. They retain their earthen color, but this can be altered by swishing them in a variety of hot liquids impregnated with bark or other vegetable matter, by coating them with white kaolin clay or paint, or through long exposure to smoke (Fig. 25). After firing, a piece may break, but it is permanently fixed.

In almost all of Africa, women are the potters. Often this is not just a personal enterprise, but a group endeavor in villages that specialize in this art form. People use domestic containers for water, cooking, and storage, as well as incense burners, pipes, and other objects. Although imported goods and local plastics have intruded on their sales, potters still have a healthy market. Some terracottas are meant for shrine use, and these frequently have more elaborate and sometimes figurative decoration (Fig. 26). A few cultures are exceptions to the female potter rule; Hausa men make pots, and there are both male and female potters among the Kongo, Dogon, Mossi, Cameroon Grasslands.

Terracotta sculpture can be made by men or women, depending on the area. Akan women, for example, are known to have created terracotta figures, while Edo men made terracotta heads in the Benin Kingdom.While we cannot be sure which gender made the Nok terracottas from Nigeria—the oldest extant sculpture south of the Sahara—or the much later Bura terracotta figures and heads from Niger, it seems likely that men made terracotta sculptures in those cultures with brasscasters, since they first model in clay and wax before casting their forms (Figs. 27, 28).

Whether pots or figures, objects made from clay have to dry thoroughly before firing, since any moisture trapped within will expand and cause the object to explode. For this reason, larger clay figures have to be hollow in order to maximize drying. Traditional African pottery is fired in the open at relatively low temperatures, not in a kiln. In sub-Saharan Africa, unlike Asia or the West, the pottery wheel is not used, nor are glazes applied.

Thermoluminescent or TL-dating dates terracotta, just as it does the fired clay core that remains in some metal castings. Dating pottery was the primary reason for its development.

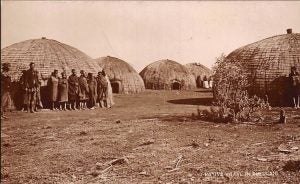

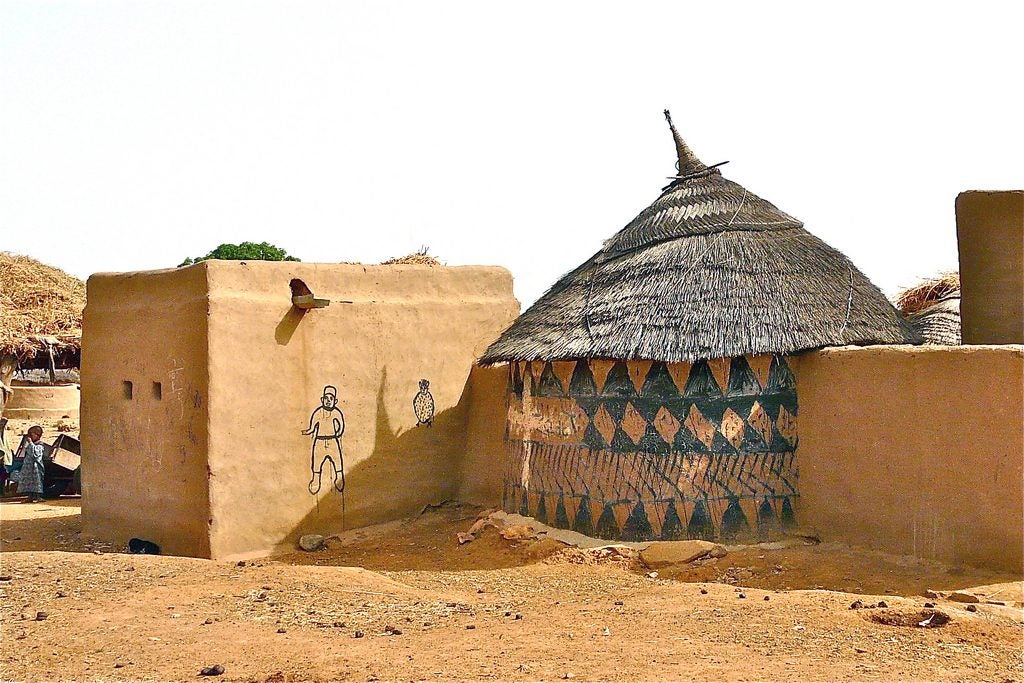

Architecture

Traditional African architecture is extremely varied in material, shape, and decoration. Permanent materials like stone (Fig. 29) are rarely used. Sun-dried clay bricks or fiber (Fig. 30) were the most typical construction mediums. Men are typically the builders, except for nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples, where women are responsible for rapid construction. The gender of those who paint the walls or model relief decoration varies according to region.

Sun-dried brick plastered with mud allows near-total construction freedom (Fig. 31): round or rectangular buildings, built-in furniture, wall niches, screening elements–all are possible. Thick walls help keep heat out despite the intense sun, and thatch directs rain away from the walls. Maintenance is required, however. If abandoned, the eco-friendly structures will break down.

Free and available, clay can create sculptural structures the same color as the surrounding earth, integrating buildings into their environment in an organic way. Roofing depends on geography. Areas with heavy rainfall have steeply pitched thatched roofs, while those in arid zones can be flat-roofed (Fig. 32).

In most parts of the sub-Saharan continent, specialized architects were unnecessary; every member of the appropriate gender knew how to build, and families and neighbors cooperated. In those regions dry enough to allow two-story buildings, such as northern Mali or the Hausa regions of Nigeria and Niger, specialized masons developed, since engineering knowledge was needed.

Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Elaborate surface decoration might take the form of mud relief or paint. Natural pigments are still used in many areas, while bright commercial colors have replaced them elsewhere (Fig. 33).

Families usually lived collectively in compounds, houses grouped together with both communal and gender-specific spaces. Most activities, including cooking, took place outdoors, so interiors were reserved primarily for sleeping and storage.

Painting

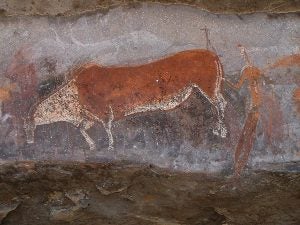

Although some of Africa’s earliest surviving art consist of paintings on rock outcrops in the Sahara Desert and in South Africa, traditional painting is otherwise uncommon–other than coloring sculpture, ornamenting the skin, or decorating house walls.

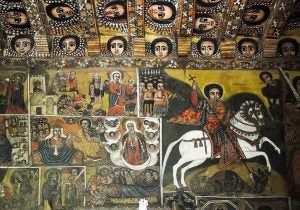

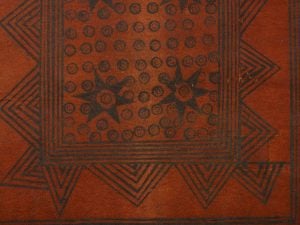

There are two exceptions, both of long-standing. One is a Christian painting tradition in Ethiopia, where church frescoes, panel paintings, illuminated manuscripts, and illuminated healing scrolls are part of a monastic tradition. Illuminations are tied to writing traditions; they are the painted illustrations that are part of hand-written documents or books. The other is found throughout Islamic Africa, and consists of abstract geometric illuminations for the Koran and prayer books (Fig. 36). This, too, is a specialty of religious scholars.

Textiles

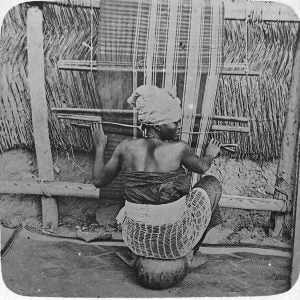

In many parts of West Africa, men weave textiles in cotton, silk, rayon, or wool after women spin the threads. Weavers then stretch the warp (the threads that form the foundation for the weft to cross) horizontal to the ground for a distance of many yards (Fig. 37). The loom is set up with one or more heddles, a mechanism that pulls a particular set of threads out of the way; weavers use their feet to manipulate them. During the weaving process, artists use shuttles, canoe-shaped wooden receptacles that hold the weft threads. They toss one or more of these (depending on the amount of colors used) back and forth through the channel(s) the heddles produce.

The resultant cloth consists of a long narrow strip between one-and-a-half and six inches wide (Fig. 38). These strips are eventually cut to a standard length and sewn together side-by-side to form much wider cloths; typically ten strips form a sizable cloth. Referred to generally as narrow-strip cloth or men’s weaves, these textiles are worn by both men and women. The weavers are professionals and often set their looms up in a group within public areas. Vendors sell unsewn strips in the market to reassure buyers they are not purchasing second-hand cloth.

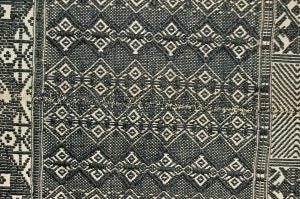

Narrow-strip cloth can be a plain, one-color weave. Stripes have historically been popular (Fig. 39), frequently made in a combination of undyed white cotton and varying shades of indigo blue. Imported dyes and threads have permitted a broad spectrum of colors. In some areas, weavers produce extremely complex patterns, such as the Senegalese weavers of manjak cloth (Fig. 40) or the kente (Fig. 41) produced by the Akan of Ghana and the Ewe of Ghana and Togo.

Women rarely weave in West Africa. All the exceptions are within a contiguous area, suggesting a common origin with a local spread: Yoruba, Nupe, Hausa, Ebira, Northern Edo, and Western and Akwete Igbo women all weave. All of these with the exception of the Igbo region also include male weavers, but until recently female weaving has been an income supplement, rather than a full-time profession.

Women use a completely different type of loom than men (Fig. 42), and generally weave individually at home. Their looms are set up vertically and produce a much wider cloth; two or three strips are enough to form a wrapper when sewn side-by-side (Fig. 43).

In Central Africa, men weave unspun fibers of the raffia palm to make flexible, lightweight cloth. To do so, they use a vertical loom (Fig. 44) and often leave the material undecorated, although dyed fibers can permit a plaid effect. In the past, this kind of raffia weaving was more widely practiced than it is today. Now it is best known among several groups in the Congo, as well as among the Ibibio of southeastern Nigeria.

Though the loom technology is not identical to that used by women, it is possible that the men’s vertical loom may have been adopted by women when raffia weaving was abandoned. Women’s use of a vertical loom is thought to have originated in one of the areas of Nigeria where it is still practiced, and spread to the others when women were enslaved. Linguistic studies of the words associated with parts of women’s looms support this idea of the technological expansion of the vertical loom.

In the Congo region, women often decorate the plain raffia cloth that men make via pile embroidery (Fig. 45). They sew a series of loops with tight spacing onto the surface, later cutting them to produce a plush surface like velvet. The effect can be elaborate, with dyed threads producing multi-colored effects or variations in the surface depth.

Another textile variety–barkcloth (Fig. 46)–was also formerly more widespread, though it still occurs in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, and Madagascar. Men remove the inner bark of wild fig trees, boil or steam it, then pound it until the fibers interlock, forming a felt that cannot unravel. Sometimes vigorous pounding produces holes, disguised through decorative patching.

Woven cloth, whether hand-woven or imported, can be further decorated through a variety of techniques. These include tie-dye (Fig. 47), stitched (Fig. 48), or starch resist, all of which shield part of the cloth from dye to produce a pattern. Cloths can also be stamped with designs.

Embroidery and Sewing

With the exception of the all-over plush embroidery of raffia cloths in Central Africa, embroidery is traditionally a male art and a full-time profession. Widely practiced in West Africa, it primarily decorates male clothing (Fig. 49). In East Africa, Swahili men’s caps are usually embroidered, as is women’s clothing in Ethiopia.

Before the advent of the sewing machine, the sewing together of strips of cloth or the tailoring of shaped garments was also a strictly male profession.

Beadwork

Many of Africa’s earliest archaeological sites include beads, attesting to a long-standing value for beads as both jewelry components and clothing elements. Some of the earliest locally-made beads were made of hand-drilled stone or shell, but glass beads were manufactured at least as early as the 11th-15th century in Ife, Nigeria. Beads were a major import even before direct trade, but European contact created an influx of beads in coral, glass, and later plastic.

Beadworkers vary in gender according to the area. In many parts of West Africa they are male (Fig. 50), while in East and South Africa women produce both beaded jewelry and clothing (Fig. 51).

Leatherwork

The gender of leatherworkers depends upon the ethnic group. In most parts of Africa, leatherworkers are men. Their work often involves appliquéing leather cut-outs onto skin backgrounds, weaving leather strips into decorative panels (Fig. 52), or creating leather cut-outs that reveal another color below.

Among the Tuareg of Algeria, Mali, and Niger, however, leatherworkers are women. They belong to the Inaden, the artisans’ caste, and create decorated saddles, cushions, sword sheaths, and bags (Fig. 53). They sell some of their leatherwork to the neighboring Fulani people, and likewise purchase some leatherwork from the Hausa.

Body Arts

In many parts of Africa, the body itself has been an art form, with human creativity altering hair and skin. Though this has taken place in many parts of the continent, it is particularly prominent among nomadic people.

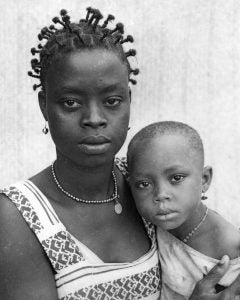

Hair can become very sculptural (Fig. 54) and can communicate not only fashionability but also ethnicity, marital status, particular professions, and achieved status. Normally hairdressers of the same gender (often friends or family members) create coiffures. Sculpture frequently depicts archaic hairstyles that are no longer worn.

Some past hairstyles for brides or wealthy women underlined their special status through crests that made it impossible for them to carry headloads, demonstrating that someone else in the household did the physical labor.

Many styles are plaited against the head, creating complex graphic patterns (Fig. 55), sometimes in combination with coiled hair or free-falling braids.

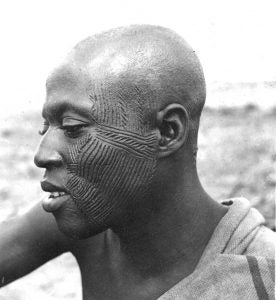

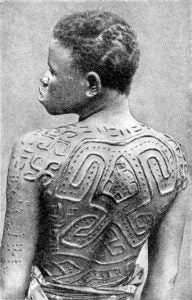

Skin can be altered both permanently and temporarily. Scarification (also known as cicatrization) is a permanent method and falls into three general categories: ethnic markings, cosmetic scarification, and medical scarification. Ethnic markings were once widespread (Fig. 56) but have been outlawed in many regions. Specialists used to mark the face of children in a pattern shared by other members of the ethnic group; herbs were applied either to raise the skin or sink it, as well as to prevent infection. Many artworks bear these facial marks. Cosmetic scarification (Fig. 57), which has also died out in most regions, was mostly a female practice and generally took place during the teenage years, as its intent was to invite touch for courtship purposes. Styles changed over time and it too often appears on sculptures. Medical scarification usually occurred during childhood, and was more random than regular in appearance. It marked the insertion of medicines to cure conditions such as convulsions, and was generally performed on the neck and shoulder region.

Another permanent alteration of the skin occurs via tattooing. Tattoos are not multi-colored, but dark due to the insertion of vegetable carbon under the skin. With the exception of West Africa’s Fulani (Fig. 58) and the Makonde of East Africa–where both genders can have facial tattooing–these marks are usually borne only by women as a cosmetic practice which has gone in and out of fashion. Tattoos usually consist of

geometric patterns on the arms, chest, or back.

Temporary skin decoration for women in some parts of Africa consists of the application of henna (Fig. 59). This is derived from a cultivated plant that is dried and powdered, then applied as a paste and left to dry overnight. When washed off, the dark red or black stain remains for about a week; it can be used as a nail stain as well. Other plant extracts are also used to similar effect.

Body paint (Fig. 60) allows frequent change and invention, and is made from natural pigments.