Chapter 3: Themes in African Art

Chapter 3.9 African Art as Inspiration

African art has inspired Western artists since the early 20th century, when Paris- and Berlin-based avant-garde artists first admired what they perceived was the carvers’ “freedom” from naturalism. They, of course, were unaware that African artists were operating under the stylistic constraints of their various cultures, their abstract stylizations taught to apprentices just as naturalism was taught in European academies. Nonetheless, their fascination with African sculptural forms (accompanied by a lack of understanding and interest in their meaning) shifted the direction of Western art history (Fig. 519). Artists such as Picasso (click here) bought masks and figures from French second-hand shops, where the families of colonial officers discarded them, or visited the ethnographic galleries of the Trocadero Museum, where the Dahomean war booty was deposited. While such early 20th-century European works were not exact replicas of African art, they adopted certain formal principles of stylization without direct interest in the cultures that produced them.

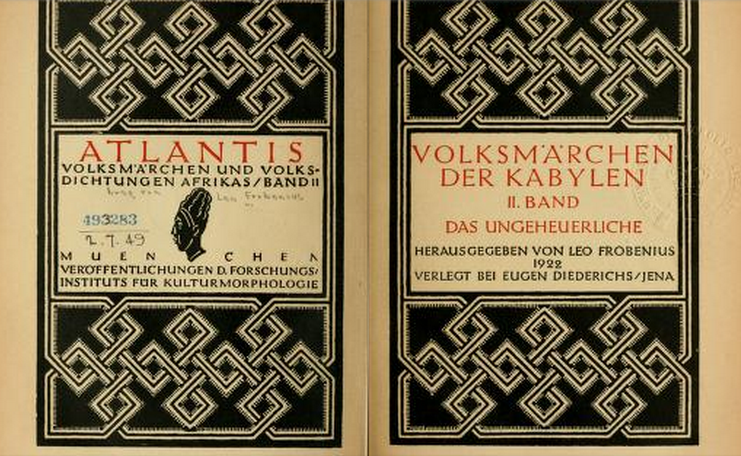

The interest generated by African art in the early 20th century extended to furniture and graphic arts as the Art Deco movement became more popular. Books with African subject matter used modified African designs for their endpapers (Fig. 520), and designers such as Pierre Legrain adapted African seats and headrests for high-end customers (Fig. 521) who may have been unaware of their inspiration, but were drawn to their sleek lines and luxurious materials.

A concurrent meaning was not always missing from this kind of stylistic mimicry and adaptation, however. African American artists, in particular, have often married African style with their own content, ranging from the self-referential to the didactic. Hale Woodruff, for example, was inspired to produce a set of murals–The Art of the Negro–at Clark Atlanta University’s library that examined parallels, convergences, and the history of the intertwining of African and European art to produce African American art. One of the murals–Muses (Fig. 522)–depicts two titular figures hovering over artists ranging from a San rock painter from South Africa to Woodruff himself. One muse is a marble-like Greco-Roman male, the other a wooden African female sculpture of ambiguous style.

Contemporary artist Willie Cole uses found objects to recreate famous African artworks, benefitting from improvements in scholarship and publication numbers in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Using bicycle parts, he channels Picasso’s 1942 assemblage of bike seat and handlebars to form a bull’s head, instead turning his attention to the African antelope in his Tyi Wara series that mimics the forms of Bamana masquerade crests. Some employ chairs to the same effect. Cole uses women’s high heels for additional assemblages, some of which also call to mind African sculptures.

Some American dress designers evidenced an interest in African cloth and styles in the 1920s, inspired by the first major exhibitions of African art in the United States (Fig. 523), although their impact was limited. Since the 1960s, however, inspired by publicity about the clothing of the representatives of the newly-independent Africans at the United Nations, the rise of the Black Power Movement, and youthful Peace Corps workers returning from Africa, American fashion has seen periodic trending of actual or adapted African textiles and fashion styles. These have included Asante kente cloth, which swept through a range of products in the 1990s and left its legacy in the graduation stoles of many African American students (Fig. 524), as well as Bamana bogolanfini and Senufo mudcloth (Fig. 525) styles that became popular in the early 2000s.

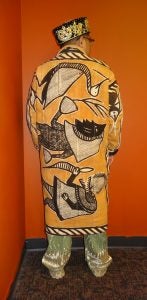

Films, stage shows, and videos set in Africa have also stimulated the imagination of working on Western productions, and by the late 20th-century scholarship had enabled art directors to access a wealth of imagery from the Continent. Disney’s Broadway production of The Lion King (1997) won director Julie Taymor the Tony for both Best Direction of a Musical and Best Costume Design. Her costumes included references to multiple cultures’ textiles, clothing, and body arts (Fig. 526). Many films set in Africa relied on generic military gear for films about warfare. A few, such as the British epic Zulu (1964), carefully reproduced African period costume, or, in the case of Out of Africa (1985), Maasai dress providing a backdrop for early colonial 20th century. Kenya’s Maasai and South Africa’s Zulu have frequently added exoticism to movies (Fig. 527); they are semi-familiar tropes that have become semi-recognizable to Western viewers via their colorful beads and herdsmen’s rural lifestyles.

When filmmakers attempt the creation of imaginary African countries, their source material often veers off into lesser-known regions or becomes a potpourri of cultural elements. Coming to America (1988) was a box office hit, and its fictional Zamunda mixed elements of West, South, and East African costumes and architectures for their contemporary fantasy royal court (Fig. 528).

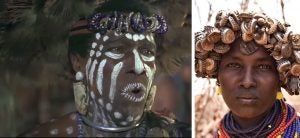

The considerably and justifiably less popular Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls (1995) included outrageously inaccurate scenes that would not have been out of place in earlier, racist 20th-century movies like Abbott and Costello’s Africa Screams. Some of the costumes and makeup were based on the peoples of Ethiopia’s Omo River Valley near the Kenyan border–however, they were jumbled together with the body paint of the Surma worn with the bottle-cap coiffures of Dassenech women and feathered headdresses from another region altogether (Fig. 529). The intention of this combination is to create a “primitive” appearance without dignity in order to produce in the viewer a sense of alienation that firmly places Africans on the other side of a self-Other divide, with admiration ruled out.

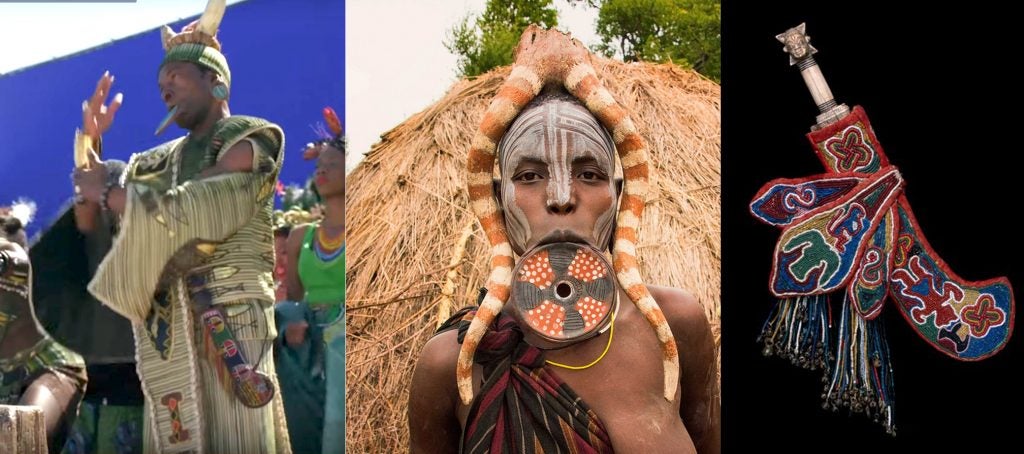

Black Panther (2018) is the first major film set in Africa to have an African American design team, and their research took them on pre-production trips to South Africa and Kenya, as well as library and museum forays into dress, makeup, and architectural sourcing from Mali, Ethiopia, Lesotho, Ghana, Nigeria, Namibia, Uganda and elsewhere. According to the comic book the film is based on, the fictional country of Wakanda is located at the juncture of Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Rwanda, but sets and costumes reference many parts of the continent, the designers taking a mix and match approach (Figs. 530, 531, 532). Their intention, like that of Deborah Landis, the Coming to America designer mentioned above, is to emphasize the beauty and diversity of African dress. In this, they were heavily influenced by a number of sources unavailable when in 1988 when Landis worked. The collaborative, full-color, large format photo books by Angela Fisher and Carol Beckwith, such as African Ark (1990), African Ceremonies (1999), Faces of Africa (2004), Dinka (2010), and Painted Bodies (2012) provided plentiful material for visual mining, as have numerous art history exhibitions and publications.