Chapter 1: Orientation to Africa and its Art

Chapter 1.3: Training and Patronage in Traditional Art

Apprenticeship

Artists’ training affects the style of their work, as do the demands of their patrons. When consistency is valued over novelty, regional or chronological stamps are apparent, allowing recognition of an art “type”. Apprenticeship–the traditional method of African art education, as it was in most of the world for millennia, favors consistency.

Whether or not traditional artists individually choose their vocation or live in a region where art is a family profession, most still undergo an apprenticeship. This training usually commences in childhood; many apprentices relocate to live with their master. If art is a family occupation, another male relative, rather than their fathers, will usually train the boys. This is meant to provide a stricter, more formal environment for learning.

Apprentices are expected to carefully watch the work of their master, but initially, their work is menial: sweeping up, bringing lunch, sharpening tools. As the years pass, the complexity of an apprentice’s tasks increase, but following the master’s methods and style remains critical (Fig. 61). In a way, the master and his apprentices constitute a brand; customers want works with the master’s distinctive stamp. This is only possible if the advanced apprentices mimic his style so that their individuality remains submerged. Since apprenticeship lasts ten years or more, this kind of patterned training becomes second nature, especially since apprentices are trained as copyists. That is, they are not asked to base the carving of a figure on an actual human being, but rather on an already sculpted piece.

An apprentice usually graduates to an assistant before becoming a master himself. At that time, he is unlikely to abandon his training to strike out in a completely different direction, for that education is internalized and reflexive. He may, however, cultivate individual touches or create new themes or object types, but the degree of novelty he introduces is dependent on the market. Art is his livelihood, not a romantic creation. If his creations are rejected, he loses income. While this may favor a conservative approach to artistic change, it certainly does not prevent creativity within established parameters.

Most African artists throughout history were in essence part-time professionals, working in the dry season and farming during the rainy season. Some wealthy kingdoms, however, required so many objects that rulers established hereditary royal guilds to supply works to the monarch and his chiefs. Although these may persist (Fig. 62), their customer base usually has expanded beyond royal courts alone, and not all family members may pursue the same vocation today.

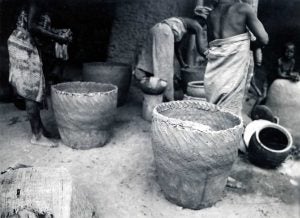

Female apprenticeship is usually more informally arranged than its male counterpart and is normally family-based, girls learning from their mothers or other women within a compound (Fig. 63).

Stylistic Consistency

Many artists have signature ways of working, which are recognizable if one examines them carefully. When they work with assistants and apprentices, some of those features–along with object types–typify the group, which is known as a workshop. It may be difficult to distinguish the hands of particular artists within a workshop, but that pursuit is part of connoisseurship.

Although there will always be variations, consistent approaches towards works throughout a region–the way eyes are treated, body proportions, the way cloth designs are organized, the shapes of pots–put a stamp on that region. The products of artists in a large ethnic group may have discernable generally joint traits, reveal commonalities that pin down a region or a city, and further exemplify aspects of a workshop or individual hand. Recognizing these varying degrees of consistency requires exposure to many works, careful observation, and good memory skills. There will always be anomalies and outliers, but “typical” works provide handy baselines for recognition.

Let’s examine a type of sculpture Yoruba carvers from Nigeria have produced for over a century: a presentation container depicting a kneeling woman holding a chicken that is actually a lidded bowl (Fig. 64). Four examples are shown here, all from the first half of the 20th century. Two are from the same workshop but were made by different artists (a, c). One (c) demonstrates lesser skills, if the coiffure is examined; the facial features on each differ, though they are in the same “family,” but the fowl’s comb is identical as is the treatment of its feathers as a series of flat bands. Another work (b) initially seems to share strong stylistic similarities, although it comes from a different region, but the chicken feathers bear extensive engraving (as do the woman’s tattoos), and the baby’s proportions are vastly different. The fourth (d) has a bulging forehead and eyes none of the others bear, as well as significantly larger ears. She bears no child, and a large face is carved on the front of her chicken container.

Yet the distinctive object type is the same, as are certain characteristics. That is, there is something discernibly “Yoruba” about the works, although there are stylistic differences even within the same workshop.

Is this true of all areas? No. Some artists are idiosyncratic, others live in multi-ethnic areas and adopt stylistic treatments from outside groups, so much so that the overlapping factor is very strong.

Factors for variants within an ethnic group can also be the result of politics and history. Nigeria’s Igbo people lived in independent city-states until the advent of colonialism and were often at war with one another. Although some object types functioned identically, their styles displayed a spectrum of difference from fairly naturalistic to extremely abstract.

The ikenga personal men’s shrines (Fig. 65), all made by Igbo artists from a relatively small sector of southeastern Nigeria, vary significantly in their approach to these figures, and there are many more variations in existence. While ikenga from a single community or cluster may share stylistic traits, the radius of a similar set is fairly small.

Patrons and Commissions

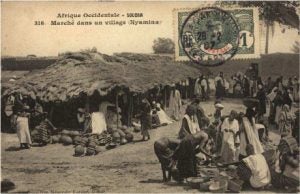

In New York, an artist might create a painting, then enter a public exhibition to display and sell it, or establish a relationship with a gallery for the same result. Traditional African artists work very differently, as most artists have throughout history all over the world–they produce most work only when a customer arranges for it and a price is agreed upon. That way they waste neither time nor materials in the hope of finding a customer. Most traditional sculpture was made by commission, which necessitated face-to-face preliminary conversation between artist and patron, with discussions about complexity and details worked out in advance. Only “lesser” items with constant sales were made in advance and stockpiled for guaranteed sales at a market: mortars, pottery (Fig. 66), cloth, decorated calabashes. Because the makers of these objects are not necessarily the vendors, buyers are only indirect patrons, and the artists receive at most only second-hand feedback from vendors about their objects’ reception.

Direct patrons typically are either individuals, representatives of a collective such as a masquerade society, or aristocrats and royals. Often they are members of the artist’s own community, although an artist’s reputation might result in a commission at some distance.

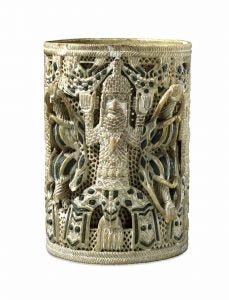

Prices generally vary according to size, complexity, and material. When kingdoms were independent states, certain substances like brass, ivory (Fig. 67), or specific bead types were sometimes limited to the ruler or nobility. Regulations of this kind are known as sumptuary laws.

Access to status materials, the cachet of employment by an influential monarch, and rewards that might include women, livestock, or property were attractive aspects of royal commissions. Some artists, like the Yoruba sculptor Olowe of Ise (ca. 1873-ca. 1938), worked primarily for royals throughout their lives, even without the existence of a royal guild system.

Olowe serves as an example of an artist who departed from many of the norms of his society’s art (Fig. 68). He was unusually adventurous in his approach to form, freeing some of his relief figures almost entirely from the background, creating tour-de-force carvings with elements such as a head trapped within an openwork enclosure (Fig. 69). Although many aspects of his style were consistent with those of other Yoruba artists (bulging, enlarged eyes; conical heads), he elongated many of his figures’ necks to an extreme degree, left the mouths open and teeth showing on some

figures, and created others with much closer-to-natural head-to-body proportions than most Yoruba work. Lastly, some of his work includes curious cultural ambiguities, with the monarch’s wife sometimes shown taller than he is, or the king and a British District Officer depicted as equals. Both instances break the traditional protocol for social hierarchy.

Olowe’s name is known, unlike that of many traditional African artists working in the past. Although their identities may have been familiar in their community or region, those who took their works out of Africa in times past were uninterested in collecting that information. Some names have been recovered through research and others might still be researched and published, but many are lost forever.