Chapter 1: Orientation to Africa and its Art

Chapter 1.4: Contemporary African Art: Materials, Gender and Training

“Contemporary African art” is a portmanteau term that includes variants that often have little in common. The art that falls into this category may be as recent as yesterday or over a century old. What “contemporary African art” shares is an adherence to at least two of the following: changes in materials, changes in patronage, changes in function, or changes in training, usually all instigated by culture contact via the colonial experience, then developing and adapting according to African interests. Contemporary art began in cities where colonialism first manifested, and spread throughout Africa. This category breaks down into three broad subcategories: export art, urban/vernacular art, and academic art. Issues relating to materials, gender, training, and patronage vary within each subcategory.

Export Art

Export art constitutes art produced for foreigners who are not near neighbors. It is often called tourist art, but much of it is not sold to tourists, but to brokers whose sales are overseas–the buyer never even meets the original seller and has no direct contact with the artist. Sometimes actual visitors to Africa or expatriates do directly commission works while on the continent, but most export/tourist art is via indirect commission, with sellers providing feedback to the remote artists: “This “x” type of sculpture sold well,” “They liked “y” sculpture, but preferred it in black rather than tan,” “The extra-large version of “z” type of sculpture sold out almost immediately–make more of that.” While some export works were made specifically for foreign patrons in the distant past, such as the late 15th/early 16th century ivories made for the Portuguese in Sierra Leone and Nigeria’s Benin Kingdom, their early date will (somewhat arbitrarily) exclude them from the “contemporary” category. The late 19th-century beginning of colonialism will mark the start of our contemporary export art subcategory.

Initially, early pieces were relatively few in number in most places and were made by traditional artists. Although they may have introduced new themes and had a decorative function, their style generally conformed to local traditional practices (Fig. 70). As artists assessed the new market and the interests of early colonial civil servants, military men, missionaries, commercial agents, and collectors, they began to adjust their habitual practices more drastically for foreign patrons. They produced different kinds of objects–toys, tables, book-ends, decorative pieces, teapots and dishes)–that foreigners desired. Some of the themes were completely new, references not only to the foreigners themselves, but to Christianity. Most of the materials, however, remained familiar (wood, brass, terracotta), and gender norms associated with materials were consistent with traditional practices. These artists trained traditionally, and simply expanded their market and output while still taking commissions from local patrons.

In areas where there were few traditional arts to inspire foreign commission, new industries sometimes sprang up. The Kamba of Kenya, for example, made relatively few non-domestic wooden objects before colonialism. As the number of British settlers grew, supplemented in post-colonial times by the visits of tourists and military rest and recreation personnel, the Kamba supplied the desire for exotic souvenirs by producing realistic animal figures and other carvings for export sale (Fig. 71), an industry that has grown to include buyers like overstock.com and Pier One.

Demand for certain art has outstripped suppliers’ abilities to source carvings. Asante figures meant to induce fertility are turned out in huge numbers, some with major variants in size and proportion, or with painted surfaces, or with fans attached to the head (Fig. 72). A good number of these are not made in Ghana, home of the Asante, but are produced in Kenya.

Urban or Vernacular Arts

Some contemporary art forms are made purely for local use, and have practical functions. The artists who create them do not emerge from the world of traditional arts, nor did they study art or architecture academically. They may, however, have undergone an apprenticeship. Their mediums tend to have been introduced from outside, usually in the 19th or 20th century. Although their products may be found anywhere, these art forms first developed in cities. There is no agreed-upon term for these objects, but urban art or vernacular art call to mind contemporary creations such as photography, advertising sign painting, carpentered furniture, cement houses, and some cement sculpture. With the exception of photography, the artists who produce vernacular art are men, and male photographers outnumber female ones.

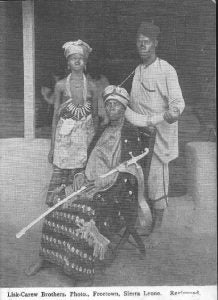

Photography appeared in Africa not long after its creation in France in 1839. By the end of the 19th century, Europeans were not the only photographers on the continent. The African American photographer Augustus Washington (b. ca. 1820 – d. 1875) brought his daguerreotype skills to Liberia when he settled there in 1853, and to Freetown, Sierra Leone by 1857. Numerous African photographers established studios (Fig. 73) and by the turn of the 20th century, photographic portraits had developed into a popular new aspect of wealthy individuals’ domestic decor. In the 20th century, affordability spread this art form throughout society (Fig. 74).

The late 20th century saw the beginnings of academic and public interest in African studio and photo-journalistic photography, and this continues to grow. Numerous publications and exhibitions concerning African photographers have increased in number and popularity, including a recent Smithsonian Museum of African Art exhibition on Chief S.O. Alonge (2014-2016), a recent book by Martha Anderson and Lisa Aronson (African Photographer J. A. Green [2017]), and continuing exhibitions of Malian photographers Seydou Keita (HERE) and Malick Sidibe (HERE) have enchanted viewers with their bold patterning and both formal and candid shots. Scholars and collectors continue to seek out lesser-known early 20th-century studio photographers’ work, as well as those who are still taking portraits.

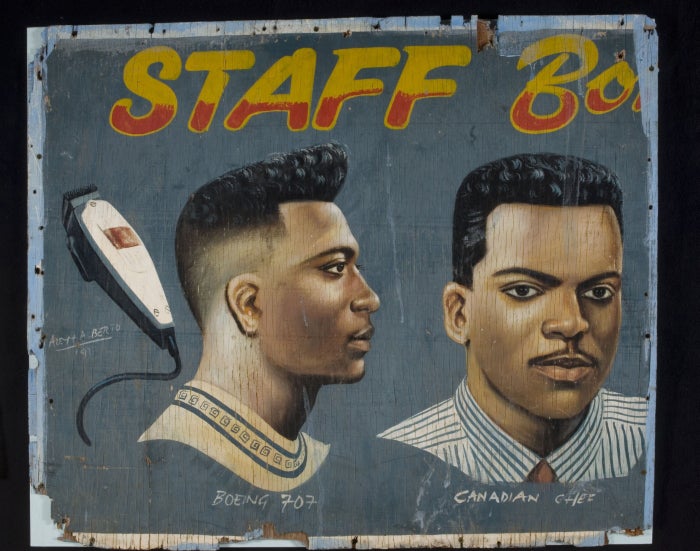

Sign painting is another vernacular art form that usually begins with apprenticeship. Although the use of signs as a form of advertising has a long history in the West, it did not begin in Africa until the economic system began to shift in colonial times. When open markets were the only economic forum, traders did not usually sell goods in the same place daily; they circulated from place to place, each with its own market day. Those selling the same type of goods clustered together, and customers forged relationships with particular vendors. When colonialism began, foreign commercial agents opened brick-and-mortar stores that might be scattered throughout a town. African shopkeepers soon joined them in an endeavor that coincided with the introduction of Western-style schools and literacy. Signboards on the stores themselves or those that advertised a business’s location became a familiar sight (Fig. 75). These were usually painted with commercial paint on wood. As the 20th century wore on, large international businesses used photo-mechanically reproduced billboards and banners to advertise, and in urban centers today often use electronic billboards, but many small businesses still employ sign painters. These painters often also paint scenes or emblems on the tailgate of large trucks (Fig. 76), as well as motifs and mottos on the side. In the last quarter of the 20th century, some sign painters began to create works that stand alone and are meant to be hung in the home.

Most sign painters are literate and frequently include words in their paintings, even those that are not advertisements. Having been influenced by foreign advertisements, they generally incline to either caricatured figures or very photorealistic ones, though some show a shaky sense of anatomy in places or a lack of perspective in depictions of furniture or buildings, as well as people who may be out of scale with one another or some of the objects around them (Fig. 77). The works tend to show motion, naturalistic proportions, and a desire to portray correct anatomy and individualized physiognomies–all traits avoided by traditional art and inspired by photography and ads.

Vernacular sculptors usually work in cement, as do some academically-trained artists. They create a metal armature and apply the cement, modeling it almost as if it were clay. Generally, these artists make memorial sculptures to stand on tombs, although sometimes they produce figures for men’s meeting houses (Fig. 78), drinking establishments, or yard decoration. They are meant to be eye-catching, and are usually painted in life-like colors.

Vernacular sculptures are also inspired by photographs and can be extremely accurate in terms of physiognomy (Fig. 79). Although sometimes head-to-body proportions are not quite naturalistic, efforts to create a realistic, usually life-size,

effect are present. Like traditional sculpture, usually the emphasis is on dignity, with important personages formally positioned, while attendants (if any are present) turn.

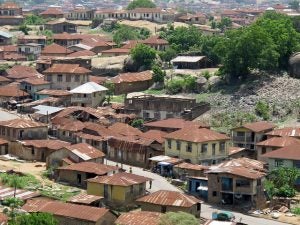

In Africa, urban architecture–except for skyscrapers–is usually the product of professional builders rather than architects. For most parts of sub-Saharan Africa (the work of Songhai, Hausa, Ethiopian, and Swahili masons being notable exceptions), multi-story buildings were introduced by African returnees or colonial powers. Bricks, sometimes plastered over, were introduced by colonists when they built government structures and their own houses in the late 19th/early 20th century, as well as by Africans who had had professional training and experience in the Brazilian construction trade before returning home after emancipation in 1888 (Fig. 80). Their Brazilian-style buildings are mostly in Lagos, Nigeria, Porto Novo and Ouidah in Benin Republic, and in parts of southern Togo and Ghana, and inspired later locally-made story buildings made from cement blocks, often with openwork elements (see Fig. 78). Today’s standard vernacular building material is cement blocks, with burnt bricks a less frequently used alternative.

In the late 19th century, European traders began to sell corrugated metal sheets as a roofing material to Africans as a replacement for thatched roofs. Despite its heat conductivity, proclivity to rust, and noisiness during rainfall, its cost initially made it a status symbol. The first adopters were monarchs and wealthy individuals, and, as prices dropped over time, this roof type became ubiquitous (Fig. 81). Thatch is rarely seen in urban areas today, and many rural areas have abandoned it as well. Roofing has moved forward to new status materials that do not rust, consisting of aluminum panels (Fig. 82).

Workshop and Academic Art

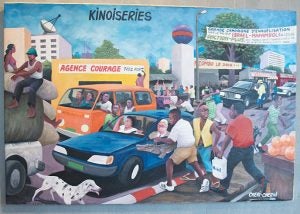

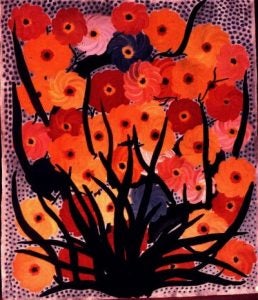

Europeans introduced education relating to arts and crafts as early as the late 19th century, when mission schools included new techniques such as carpentry and Western-style embroidery in their curricula. In the first half of the 20th century, some individuals pursued art studies overseas (often in the colonial “mother country”) at art schools and universities. At the same time, some foreigners resident in Africa began art workshops in painting and/or sculpture for interested individuals, some of whom had little or no formal schooling. They supplied paint, brushes, and canvases or other Western materials, and–to greater or lesser degrees–suggestions regarding subject matter and style. Because of their international connections, these workshop leaders were able to arrange for their artists’ works to be exhibited outside the continent and achieve international recognition. Although numerous workshops of this type were active (and some still are), particularly prominent examples were the Poto-Poto school of painting in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, instituted by Pierre Lods in 1951; the school of Lumbumbashi in Democratic Republic of Congo, established by Pierre Romain-Desfossés in 1946 (Fig. 83); and the Mbari Mbayo clubs at Ibadan (1961) and then Oshogbo (1962), Nigeria, led first by Ulli Beier and Suzanne Wenger, and then by Ulli and Georgina Beier. The artists and sculptors in these enterprises generally painted in an abstract manner in tune with Western sensibilities, but with localized subject matter. Almost all workshop artists were men, with some notable exceptions, such as Nigeria’s Ladi Kwali, a ceramicist.

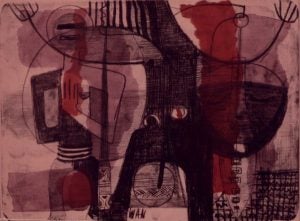

Once African universities and polytechnics began proliferating, degree-granting art programs emerged. Expatriates and those Africans who had studied art abroad were the initial instructors, and curricula followed Western models. Painting and drawing, prints (Fig. 84) sculpture (with chisels and hammers for stone, as well as the use of welded steel, plaster, fiberglass and cement), ceramics (with glazes, pottery wheels, and kilns), textiles (with Western-style looms), photography, graphic and industrial design, and architecture (using steel, glass, and poured concrete) became standard tracks of study, and no gender restrictions for artists existed. A woman might be a sculptor, a man a potter. Works were divergent in style, but abstraction (at least to a degree) tended to trump realism.

Some African artists continue to train at overseas art schools or universities. These institutions’ training has expanded beyond the curricula of the 20th century, and students are involved in creating installations, performance pieces, and multimedia experiences. The 21st-century trends in overseas schools have pushed identity exploration and politically-charged subject matter, and artists who undergo this education often produce works that are vastly different in spirit and appearance from their Africa-trained colleagues. Because these artists are familiar with the art business in major Western cities, they begin their careers knowing that cultivation of relationships with reviewers, dealers, galleries, and curators can have a major impact on their progress, and are aware of grants, fellowships, residencies, and competitions that will increase their prominence. In order to escape from obscurity in the midst of many other artists, they often parlay their “Africanness” in line with art world trends. Similarly, artists whose parents are African but were themselves brought up overseas (or relocated there in childhood) often find Africa-focused style, subject, or rhetoric to be effective routes to recognition (Fig. 85). Departure from this distinction is not always met with a positive response.