Chapter 2: Analyzing and Discussing African Art

Chapter 2.5 Contextual Analysis

Normally art history requires a combination of both contextual and stylistic analysis, because artists often use style to support the ideas they wish to communicate. A knowledge of the specifics of a culture and its art is necessary to contextual analysis, as its name implies, whereas stylistic analysis can be applied to objects completely unfamiliar to the viewer. In a contextual analysis, the manner in which the stylistic elements, principles of design, and “rules” support meaning are usually elucidated. In traditional African art, the way an object is used is also discussed. For traditional pieces, the aspects a viewer should address are threefold: style, meaning, and function. Depending on the artwork, these may be addressed equally or one or two may require greater emphasis in a discussion.

For the purpose of teasing out the three threads of a contextual analysis of a traditional African sculpture, phrases will be color-coded, with dark turquoise marking stylistic observations, red marking those of meaning, and purple indicating function.

This unusually large-scale [stylistic] sculpture (Fig. 142) represents Glele, the monarch [meaning] of the Fon people of Dahomey from 1858-1889. Half-animal, half-human representations are rare in sub-Saharan Africa, but several 19th-century Fon monarchs were represented this way [stylistic]. Also atypical [stylistic]–particularly for royals–are the figure’s break with frontality (it twists slightly at the shoulders), active pose, and lack of self-composure, [stylistic] its bared teeth speaking to ferocity rather than the dignity of most royal representations [meaning]. Some of these surprising features are due to the artwork’s purpose. Although it was part of the public display of the king’s wealth during an annual ceremony, it functioned as a royal bo or bocio, a power object activated and reinforced by mystical medicine [function]. Brought to the battlefield, it was believed to influence the outcome positively, its aggression underlined by the bared teeth, the two swords it originally held [meaning], and its forward momentum. Its sense of dynamism is reinforced by the diagonals of upper and lower legs, arms, and inclining chest. The tail helps balance the gesturing arms, its curves mirrored by the rounded rump, calves, shoulders, and the back of the head [stylistic]. The head and torso represent those of a lion, although they are far from naturalistic, only leonine via the teeth and the wavy lines representing the mane on the torso and the back of the head [stylistic]. Each king had several associated symbols that derived from divination configurations that took place even before his reign. These became his “strong names”, monikers of praise that might appear as statues, appliqued umbrella motifs, or other forms of visual, as well as oral, expression. One of Glele’s names was “lion of lions,” and the lion appeared on many of his objects [meaning]. Only in this sculpture, however, was it anthropomorphized, its life-size royal alter-ego absorbing and deflecting evil intentions and actions. Believed to have the powers of locomotion, it could take measures to strike down enemies and protect the state and the throne [meaning].

Could other aspects of the sculpture be discussed, such as its breeches, the type of swords it once held, and why the artist’s rendition of a lion holds little resemblance to the actual animal? Certainly. Even the proportions of how much discussion is devoted to style, meaning, and function can differ, as long as the essential points are covered.

Our contextual analysis of contemporary artworks is partially dependent on how clearly the artist communicates his message, or discusses it in interviews.

Sometimes cultural context may be self-evident, but the artist may obscure his or her meaning intentionally, drawing on personal symbolism that may not be shared with scholars or art journalists.

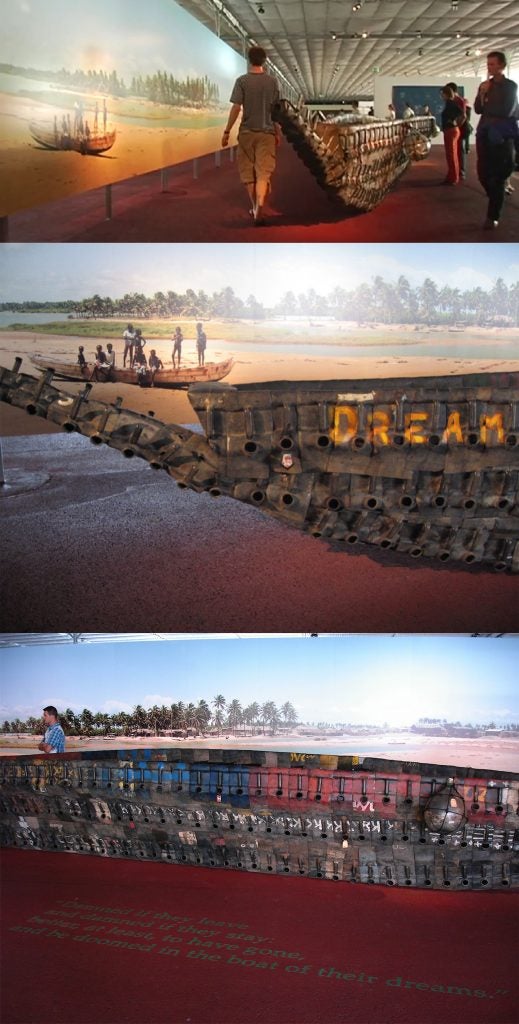

This installation (Fig. 143) places a large boat against a huge photo mural of the West African coast. The vessel is assembled from plastic jerry cans, used locally to transport petroleum. Its name, “Dream”, is inscribed on the prow. Romuald Hazoume has frequently reused these containers in his art, using single ones turned on their side to represent masks or faces with round open mouths, the handles serving as a long rectangular nose [stylistic]. He has also employed them in installation layouts, sometimes as literal references to the illegal and dangerous Beninois trade in petroleum across the Nigerian border. Here he comments on the desperation of some poor Africans who, trying in vain to obtain visas to emigrate to Europe, pay huge sums to be smuggled, first to North Africa, then across the Mediterranean, often losing their lives along the way. Hazoume also refers to his own dream–that the Benin of the photo mural should have good schools, potable water, dependable politicians, and be a safe and progressive country whose citizens have no desire to leave [meaning]. In interviews, he has commented that he doesn’t want to sell this work, but would prefer to exhibit it in Benin and elsewhere in Africa as a goad to those in power to improve the lot of their citizens and bring Africa onto the world stage in a positive way [function].

The above analysis has little to say about style. Its only comments actually refer to other works the artist has created using the same materials, albeit to a different purpose. It is almost entirely a discussion about meaning. Function might be summed up as “art for a didactic purpose.”

Comparing and contrasting two artworks is again a useful way to elicit observations that might not immediately come to mind when viewing a single work. Contextual comparisons also examine style, meaning, and function, although any given pair may favor one or two aspects over another. Points of comparison might be found in style or in meaning or in function–the viewer has to consider the two works to tease out where the comparisons lay. Contrasting aspects usually become easy to spot.

A full comparison can be found in the two works below (Fig. 144). In order to make it useful, we’ll use one of the single works whose context we’ve already discussed, and another whose style we’ve analyzed, adding contextual information. Again, the descriptive text is color-coded to clarify which parts of the comparison focus on style (turquoise), meaning (red), and function (purple). Editorial comments that are not part of the analysis are highlighted in yellow and placed in brackets. Terms in bold exemplify how a reader can be reminded that a comparison is being made–the two works are not simply discussed separately.

While these works both represent monarchs of sizable kingdoms [meaning], their interpretations are drastically different. [the author then has to make a choice of what to stress first] The Benin sculpture emphasizes the monarch’s dignity and status [meaning] through his frontality, stillness, hieratic scale, and the presence of an entourage [stylistic]. His great wealth is alluded to by the brass used to create the sculpture, as well as his profusion of expensive imported coral jewelry, brocaded wrapper, and the pestle staff in his right hand balanced by the stone axe head in his right, a relic of the god of death that has the ability to make his words manifest [meaning]. These last two objects underline his duality; he has earthly power and supernatural power as a divine king [meaning]. Although the monarch of Dahomey was also a divine king, his sculpture emphasizes only his forceful aggression, used to protect his country and slaughter his enemies [meaning]. The diagonals of the figure’s arms, legs, and forward-leaning posture produce a sense of movement, unlike the permanence provided by the multiple verticals of the Benin work [stylistic]. This figure once held a sword in each hand, his sharp teeth underlining his ferocity [meaning]. The court art of both kingdoms sometimes depicts rulers who are part-human, part animal. Here the Fon monarch is half-human, half-lion. While the Benin ruler is shown here in human form, he is sometimes portrayed with mudfish legs, an allusion to his identification with Olokun, god of the sea [meaning]. Both portray specific kings. This is Benin’s Oba Ewuakpe, who restored the wealth and prestige of the monarchy; he is identified by the decorated pestle in his right hand [meaning]. The Fon sculpture represents Glele, one of whose praise names was “Lion of Lions.”[meaning] The two works’ very different usage influenced both their materials and expression. The Ewuakpe bronze acted as the central decoration of his ancestral altar, a portrait [function] of his eternal qualities as a royal ancestor: his posture and expression remain serene and untroubled [meaning]. Glele’s representation, on the other hand, properly represents the confrontational readiness and potential violence [meaning] necessarily to a royal bo, a power figure reinforced by supernatural medicine that was mounted on a rolling cart. While displayed at the king’s annual tribute ceremony as a reminder of his supernatural and worldly power, its presence on the battlefield was both psychological–heartening the Fon troops and demoralizing and confusing the enemy–and mystical, for it was believed to be able to move on its own to destroy opposing forces [function].

Again, this analysis could further develop style, meaning, or function. The Benin figure has greater mass, the Dahomean sculpture demonstrates the artist seems unfamiliar with the structure of an actual lion’s head. Other lion representations of Glele could be mentioned, or how deceased Benin monarchs were honored at their altars could be discussed. No comparison of head-to-body proportions was included, nor were textures discussed. These could have been added to the comparison, but a discussion of the meaning of the two works and the main elements of design that support that meaning is critical. Neither that discussion nor the purpose of the two works should be excluded.