Chapter 3: Themes in African Art

Chapter 3.1 Animals

Why Animals Appear

Animals frequently appear in traditional African art, but they are rarely chosen randomly as simple representations of the natural world. They can serve as accessories indicating status, such as the horse, who is an expensive animal that also elevates his rider above others. Showing a figure atop a horse is a common indicator of a great warrior, even when horses were rare in the area and thus unfamiliar to the artist. Even where horses were known, such as the Oyo Yoruba use of cavalry, the primacy of human beings means that the scale relationship of man to equine is rarely natural–hieratic scale usually ensures man will dwarf animal (Fig. 145).

Powerful animals can serve as metaphors, such as the leopard and elephant who frequently symbolize monarchs or chiefs. These animals often serve as verbal metaphors for powerful figures as well. The Oba of Benin Kingdom, for instance, is referred to as the “leopard of the house,” while his animal counterpart is the “leopard of the bush”. One 15th-century Benin king’s appellation was “the brave ambidextrous leopard who never misses his target.” When this monarch is sleeping, his courtiers say, “The leopard is in his shelter”; if ill, “The leopard is sick in the wilderness.” Why the leopard? Its beauty and deadliness echo those of the ruler. He was traditionally the only individual permitted to take like, though he might designate that right to certain courtiers, including his chiefs who were generals and their commanders. Soldiers wore tunics either made from leopardskin or from cloth with embroidered leopard features, as well as brass hip pendants in the shape of a leopard’s head, confirming the Oba’s sanction to kill (Fig. 146).

Elephants can symbolize the monarch in some parts of Africa, but in the Benin Kingdom they tend to represent powerful chiefs, sometimes those who attempt to rival the Oba. In the 18th century, the Iyase, the leader of the most elite group of chiefs, rebelled and had a contentious relationship with two successive monarchs. When he was finally defeated, the victorious Oba had his artists create several works that showed him standing atop the elephant, emphasizing his triumph (Fig. 147).

As we saw in Chapter Two, some animals represent praise names of specific rulers, as they did among the Fon of Dahomey Kingdom.

Liminal animals, previously discussed, often refer to persons of power who straddle this human world and the spiritual world. Kings, priests, and witches have these abilities, which are often executed at night. Bats, birds, crocodiles, tortoises, mudfish, and pythons often appear in African art with such meanings.

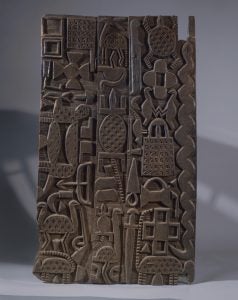

Sometimes a bird is simply a bird, especially when it appears in a context with a mix of other animals, such as on a Nupe door (Fig. 148). However, even when animals reflect creatures from the natural world, they may have contextual layers of meaning. The Zulu, for example, attach high importance to cattle. In the past, cattle represented not only their everyday way of life as pastoral herders, they represented bridewealth, the number of cows a husband had to pay to his new wife’s family. Houses were organized in a ring around the cattle enclosure, and ancestors were buried in the enclosure, with cattle sacrificed at their funerals. Zulu neckrests, used to support the head at night, often included references to cattle horns, since ancestral spirits often spoke to sleepers through dreams (Fig. 149).

In contemporary art, animals may be featured as signifiers of Africa and its exotic elements. An early 20th-century corporate headquarters in Cape Town, South Africa, for example, included African animals on its exterior and interior, distinguishing markers that showed local affiliation rather than extra-continental ownership (Fig. 150). Likewise, contemporary export art often includes images of antelopes, fish, snakes, and other animals as reminders of wilderness and nature.

Additional Readings

Abiodun, Rowland. Yoruba Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Anderson, Martha G. and Christine Mullen Kreamer. Wild Spirits, Strong Medicine: African Art and the Wilderness. New York: Center for African Art, 1989.

Ben-Amos, Paula. “Men and animals in Benin art.” Man n.s. 11 (2, 1976): 243-252.

Ben-Amos, Paula. “Royal Art and Ideology in Eighteenth-Century Benin.” Iowa Studies in African Art 1 (1979): 67-86.

Blackmun, Barbara. “The face of the leopard: its significance in Benin court art.” Allen Memorial Art Museum Bulletin 44 (2, 1991): 24-35.

Nevadomsky, Joseph. “Signifying animals: the leopard and elephant in Benin art and culture.” In Stefan Eisenhofer, ed. Kulte, Künstler, Könige in Afrika: Tradition und Moderne in Südnigeriae, pp. 97-108. Linz: Oberosterreichisches Landesmuseum, 1997.

Roberts, Allen F. Animals in African Art: From the Familiar to the Marvelous. New York: Museum for African Art, 1995.

Saharan Petroglyphs and Paintings

Some of Africa’s oldest art forms feature animals, often clearly in motion, unlike later renditions. The exact meaning of these renditions cannot always be unpacked, but they clearly show keen observations on the part of the artists involved, as well as considerable preliminary practice, possibly through drawing in the dirt first. While we can’t, perhaps, speak of “professional artists” from this period, it seems

likely that specialist artists emerged, since certain works betray a sense of ease and confidence in line and form that are the result of consistent trials and refinement.

A huge expanse of the northern third of the continent is occupied by the Sahara desert, yet it has not always been barren land. While most of it was sand, apparently for millennia, about 12,000 years ago monsoons swept over the area repeatedly, changing it to savannah grasslands that supported giraffes, elephants, lions, hippos, rhinos, ostriches, and a large, now-extinct variety of wild buffalo (Bubalus antiquus). The Africans who lived in the area now part of Niger, Libya, Algeria, and Morocco commemorated these animals’ presence through petroglyphs, or rock engravings, that they ground into rock outcrops with stone tools (Fig. 151). These petroglyphs are the only remaining art form from the period, which ranges from about 10,000-6000 BCE, when the climate shifted and became less moist, no longer able to support these animals.

The smooth, fluid lines of many of these incised drawings belie the tedious nature of the task. The creation of each line would have been a time-consuming procedure. Some images, such as the Dabous giraffe petroglyph (Fig. 152), are life-sized and include interior lines indicating the animal’s markings. They were incised in sandstone, the same material used for the Mt. Rushmore presidential heads, the Great Sphinx, and many other world monuments. Sandstone’s hardness is measured as 6-7 on the Mohs scale (a diamond is 10), so creating these lines was no mean feat. Even the hairs on the spinal ridge are indicated.

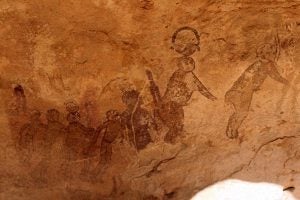

From about 8000-6000 BCE, petroglyph production overlapped with paintings made from natural pigments. The weather pattern had changed; whether the population did as well, or whether their art forms merely took a different direction is unclear, but animals no longer were the center of their depictions. Instead, in this so-called Roundhead Period (Fig. 153), human forms began to dominate. Although their bodies are physically recognizable, they are less skillfully-wrought and naturalistic than the earlier petroglyph animals, and with far less variety in pose. Their heads are featureless and helmet-like, their bulky bodies sometimes showing dotted lines of body paintings. Particular works may show greater sophistication in depicting depth–overlapping and diminution as distance increases–but tend to lack grace.

As the climate continued to shift, so too did the populations and their lifestyle. Reduction in the lush landscape sent

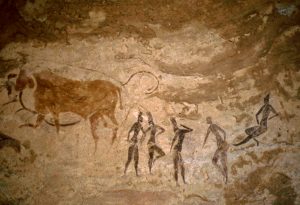

drove certain animals southward, and the emerging savannah grasslands became home to peoples who herded cattle, rather than following a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. They too produced paintings rather than petroglyphs, documenting not only their herds but themselves (Fig. 154). These skilled works also seem to have been the work of specialists, and they gathered earthen pigments, combining them with milk and egg yolk to bind the paint onto rocky surfaces. This period is variously known as the Pastoral, Bovine, or Bovidean Period, dating from about 5500-2000 BCE.

Depictions of people in these images show them in elegant silhouette form (Fig. 155), their heads and other extremities small in proportion. They are situated in informal poses, conversing, relaxing, playing with their children, hunting, and herding. These paintings seem to be neither iconic images nor religious works, yet–like the petroglyphs–we have no absolute knowledge of the motivations behind them. Both the makers of rock engravings and the paintings of the cattle herding period appear to have been nomadic, so they did not mark permanent settlements (although they may have been revisited). Nomadic peoples have periods of idle time between hunts or while the cattle are grazing–did they create these for sheer pleasure? That remains unknown.

That the cattle are depicted on the paintings in specific ways–that is, their marking individualizes them in a portrait-like manner–yet the people remain featureless silhouettes may indicate beliefs that recognizable human images could potentially harm the living. However, cattle are so important to herders that it seems unlikely that, with such a belief in mind, the artists would expose cattle to a similar vulnerability through visual representation. Both people and animals are treated with sophisticated conceptual approaches. They are frequently shown in motion, and depth is suggested both through overlapping and positioning on the surface (i.e., things further away are placed towards the top of the composition).

When the climate continued to dry out, the cattle and their owners also apparently moved south. Paintings of people with horse-drawn chariots (1000 BCE-1 CE), followed by camels and riders (beginning ca. 200 BCE) followed (Fig. 156) as desertification intensified. While animals continued to be somewhat naturalistic, the incoming Berber populations generally distorted images of people or constructed them geometrically.

Further Reading

Bradshaw Foundation. “The World’s Largest Rock Art Petrogylph: Giraffe Carvings of the Sahara Desert.”

Hansen, Jörg W. Tassili: art rupestre dans les Tassilis de l’ouest et du sud algérien = rock art in the western and southern Tassilis, Algeria = Feldsbildkunst in den westlichen und südlichen algerischen Tassilis = arte rupestre nei Tassili dell’ovest e del sud algerino. Paris: Somogy éditions d’art, 2009.

Holl, Augustin F. C. Saharan rock art: archaeology of Tassilian pastoralist iconography. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2004.

Soukopova, Jitka. Chronology, origins and evolution of the Round Head art. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars, 2012.

South African Rock Paintings: Game Pass Shelter

South Africa and its neighbors are also the site of numerous examples of rock art. These are primarily paintings, but their dating range is more encompassing than those of the Sahara. Created by the San peoples, the region’s original inhabitants, they were first made as early or earlier than some of the desert artworks and continued into the 19th century. Until recently, their dating was difficult–it involved flaking off large pigment sections for carbon-dating, which destroyed the works. In 2017, a variation of carbon dating was used. This method–accelerator mass spectrometry radiocarbon dating (AMS)–uses very small sample sizes. Tested at 14 sites, the oldest of these (in Botswana) yielded dates circa 3700-2400 BCE.

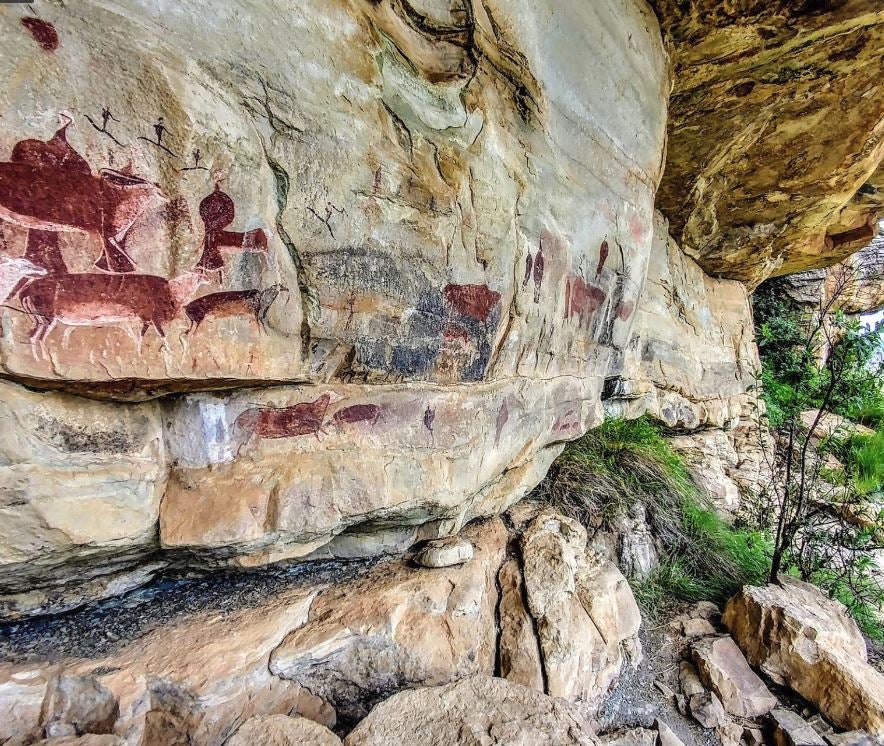

Most southern African rock paintings depict animals and/or peoples, and were interpreted for a long time as descriptive, recording scenes the San artists–who were hunter-gatherers–were familiar with. Not all paintings, however, seemed to depict solely natural scenes. One particular set of paintings, located in the Game Pass Shelter of the Drakensberg mountains (Fig. 157)–a region with the highest concentration of rock art in southern Africa–provided clues that led to a new interpretation of the artworks there and elsewhere.

The San no longer live in this area. White settlers pushed them further west in the 19th century, although they still inhabit Namibia, Botswana, and bordering areas of South Africa. When documented regional San religious traditions recorded in the 19th century were considered in respect to one of this rock outcrop’s paintings (Fig. 157), a new hypothesis

emerged, and this was strengthened by knowledge of the current healing practices of Western San ritual specialists. The latter are able to bring supernatural forces into play by either going into trance during group dances or dreaming in a trance state. Trances are induced by elements that focus on the notion of spiritual potency (n/um)–this could be certain songs, the sacrifice of a particular animal, a particular place. The healer, when participating in a group dance, becomes more and more attuned to the spiritual world and begins to quiver, stagger, sweat, lower their head, and bleed from the nose as they fall into a trance, a process referred to as “dying”. In that state, they touch those with disorders and heal them, or may experience hallucinations that provide insight. Nineteenth-century accounts from the southern San report ritual specialists similarly quivering when apparently asleep, their powers exercising. Besides healers, ritual specialists might have expertise in controlling rain or game, or choose a malevolent path as a sorceror.

Asleep or awake, in trance they are believed to achieve out-of-body experiences involving transformation into a variety of animal forms, some of which are considered more spiritually potent than others. Although San artists painted many types of animals, the eland, the largest variety of antelope (Fig. 158), appears with greatest frequency. Artists painted eland in a surprising variety of poses, including views from the hindquarters, and gave its anatomy more attention than that of other animals, even including modeling through shading and highlights. It is associated with extreme potency, its fat is used in numerous San rites.

One of the Game Pass Shelter’s painted passages–sometimes called the “Rosetta Stone” of San rock art because its interpretation helped decode paintings throughout southern Africa–concentrates on a dying eland with nearby humans (Fig. 158). The San use poisoned arrows to hunt eland; the poison acts on their system by making them lower their heads and turn them from side to side. They sweat, their bodies tremble, the hair along their spine erects, they stagger, and finally collapse in death. This depiction shows the death throes, white dots representing sweat, one front leg bent while the back legs cross in a stagger, the head lowered and turning, and spinal hairs standing straight up. The figures behind the eland, however, demonstrate that this is no simple hunting scene.

One elongated figure (Fig. 159) stands immediately behind the animal, gripping its tail. Its head is antelope-like, not human, and white dots of sweat surround it. Tellingly, its legs are crossed in a staggering position, and white-tipped hooves replace its feet. The spiritual potency of the dying animal has been transferred to the ritual specialist, who is transforming into an eland in his trance state. Behind him are additional figures in various stages of transformation. One bends forward at the waist, another is covered with a tented skin garment (kaross), while a third (Fig. 160) also bears an eland head, sheds sweat, has upright body hair rendered identically to that of the eland, with both hands and feet transformed into hooves. They are therianthropes, metamorphosed shape-shifters who can cross the borders into the spiritual world.

Other paintings in Game Pass Shelter depict multiple elands accompanied by human beings enveloped in skin garments (Fig. 161). These cloaks’ shape mimics the hump of the antelopes, and their heads have already transformed to animal forms, their feet to hooves. Other locations may depict figures who are human and merely wearing skins with the head attached, or even masks (though the San are not known to have ever used wooden masks). The hooves of these figures preclude the notion of a disguise in this case, but there are other San paintings that suggest that even the act of kaross-wearing may have been intended to facilitate trance and transformation.

Game Pass Shelter and the Drakensberg’s other rock art have become a UNESCO World Heritage site when the entire uKhahlamba-Drakensberg Park was so declared in 2000. Although the San were said to no longer live in the area, both government agencies and UNESCO recognize the presence of a local clan that intermarried and assimilated among neighboring peoples in the 19th century in order to survive. Their self-recognition as San–as well as their neighbors’ awareness of their origins–continued. One man recalled coming to one of the Drakensberg caves in the 1920s, his initiator using painting as an instructional aid. Since 2002, a growing number of this “hidden” clan’s members has been using the Game Pass Shelter site in an annual attempt to communicate with their ancestors, limited in part because of site restrictions on fire and the enforced presence of outsiders at a private rite.

Further Reading

The African Rock Art Digital Archive. http://www.sarada.co.za/#/library/

Bonneau, Adelphine, David Pearce, Peter Mitchell, Richard Staff, Charles Arthur, Lara Mallen, Fiona Brock, and Tom Higham. “The earliest directly dated rock paintings from southern Africa: new AMS radiocarbon dates.” Antiquity 91 (April, 2017): 322–333.

Dowson, Thomas. “Debating Shamanism in Southern African Rock Art: Time to Move On . . . ” The South African Archaeological Bulletin 62 (185, 2007): 49-61.

Jolly, Peter. “Therianthropes in San Rock Art.” The South African Archaeological Bulletin 57 (176, 2002): 85-103.

Lewis-Williams, J. David. Believing and seeing: symbolic meanings in southern San rock art. London: Academic Press, 1981.

Lewis-Williams, J. David. “A Dream of Eland: An Unexplored Component of San Shamanism and Rock Art.” World Archaeology 19 (2, 1987): 165-177.

Lewis-Williams, J. David. “The Thin Red Line: Southern San Notions and Rock Paintings of Supernatural Potency.” The South African Archaeological Bulletin 36 (133, 1981): 5-13.

Lewis-Williams, J. David, G. Blundell, W. Challis and J. Hampson. “Threads of Light: Re-Examining a Motif in Southern African San Rock Art.” The South African Archaeological Bulletin 55 (172, 2000): 123-136. 67.

Lewis-Williams, J. David and David G. Pearce. “Framed Idiosyncrasy: Method and Evidence in the Interpretation of San Rock Art.” The South African Archaeological Bulletin 67 (195, 2012): 75-87.

Ndlovu, Ndukuyakhe. “Access to Rock Art Sites: A Right or a Qualification?” The South African Archaeological Bulletin 64 (189, 2009): 61-68.

Prins, F. E. “Secret San of the Drakensberg and their rock art legacy.” Critical Arts 23 (2, 2009):190-208.

Smith, Benjamin. “Rock Art in South African Society Today.” In L.M. Brady and P.S.C. Tacon, eds. 2016. Relating to Rock Art in the Contemporary World: Navigating Symbolism, Meaning and Significance, pp. 127-156. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2016.

The Ciwara of Mali’s Bamana People

The Bamana people of Mali are one of the Mande-speaking peoples, many of whom were part of a succession of empires and kingdoms that persisted until the 19th century. Although the majority of Bamana are Muslim today, as recently as the 1970s a substantial number of Bamana practiced traditional religion, even though Islam and lifestyle changes had already had a significant impact on culture. The Bamana and many of their rural neighbors live in a casted society; that is, to a great extent birth determines occupation and marriage patterns. Farmers–landowners–constitute the nobility; other groups consist of artists/artisans (nyamakalaw, or “power handlers”), while slaves once constituted a third societal category. Daily rural life used to be organized around initiation societies with varied specialized purposes. One, the Ciwara Society, was organized around young farmers and a spiritual connection to the land.

During the planting season, then and now (see video below), young men from their late teens to early 30s clear the fields in communal efforts, drummers and women’s song spurring them on. Up until the early 20th century, male masqueraders danced in the fields, usually in pairs representing a male/female (often with a baby) antelope or in threes–their fertility and the fertility of the fields were linked. Antelope imagery alluded to the supernatural being Ci Wara, a half-human, half-animal spirit that generally adopted an antelope form. He taught agriculture to the Bamana during primordial times until, disappointed with mankind’s behavior, he disappeared into the ground. The masquerade headpieces made in his memory–also called chi wara or tji wara–bear his name, which is also accorded to champion farmers to praise them as they work hard in the fields.

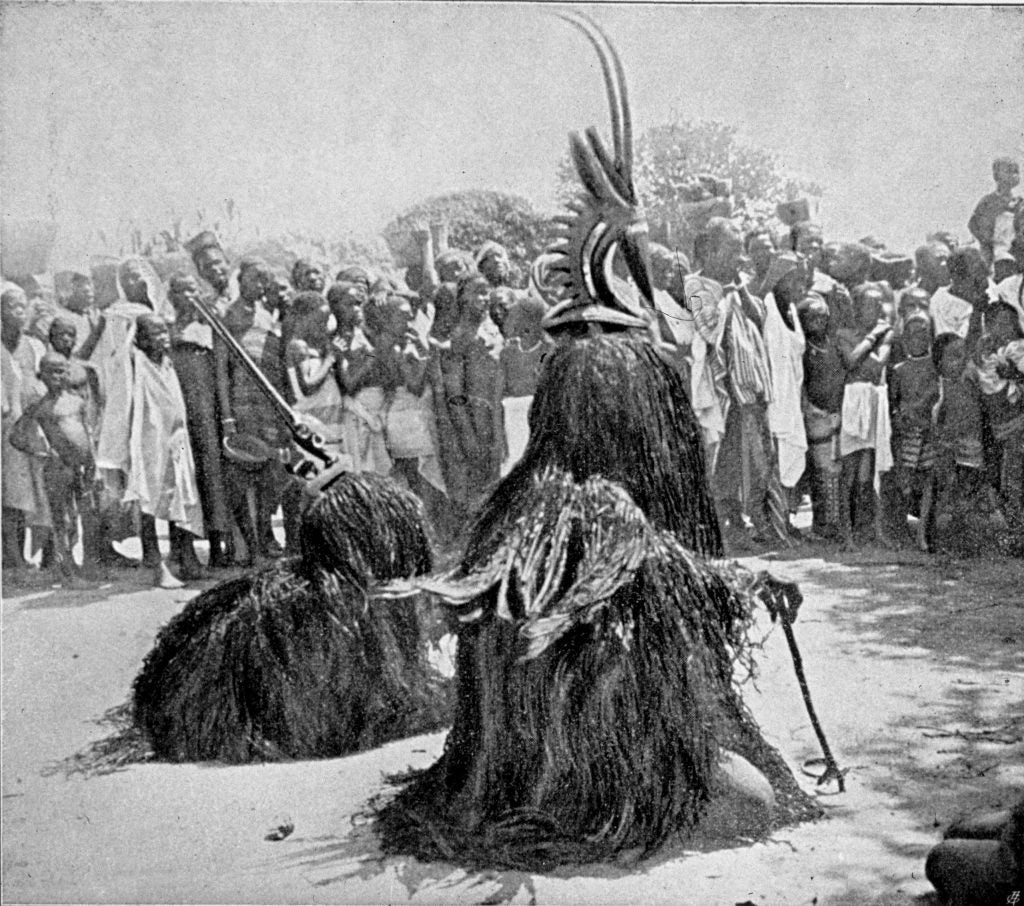

A community’s Ciwara society kept a shrine containing a boli power object that acted as an altar for the spirit of Ci Wara, receiving periodic sacrifices. Masquerades took place before the rainy season, a time when fields were cleared in preparation for planting, as well as during the rains, and at harvest time. Performers danced with their bodies bent forward, holding sticks that represented front legs. The animal carvings were not true masks–that is, they did not cover the face. Instead, they were attached to basketry caps secured to the head, with a fiber costume made from wilderness materials covering both the upper body and face of the masqueraders (Fig. 163); in the Mande Plateau area of south-central Mali, birds’ feathers are added to the costume. When not in use, these masquerade crests were stored in the shrine near the boli, soaking up some of its spiritual power. A small piece of the boli would be buried along the masqueraders’ route and turn the first female crossing it into the champion of the women; the male antelope masquerader would eat her food. Another boli piece was attached to one of the male antelope dancer’s sticks or in the basketry cap on his head, while the masquerader portraying Ci Wara’s wife had a piece of the boli in a leather bag at the back of his waist. These empowered the dancers and probably the community’s farming as well.

By the turn of the 20th century, some communities danced in the village square rather than in the fields, and by the mid-20th century, growing Islamicization and Bamana migration to cities continued to impact the initiation society. Some ritual performances were now solely entertainment, danced in front of the mosque on Muslim holidays. As the initiation society transformed, other farming organizations–both paid and charitable–emerged. Some of these also commissioned antelope masks to perform in the fields just before the rainy season, while others danced in town. Many of these crests looked like the ciwara, since the same artists were responsible for making both. Those sculptors were nyamakalaw blacksmiths, who are the carvers among the Baule, in addition to forging metal objects and acting as ritual specialists (see Chapter 3.5). As the 20th century progressed, field performances of any kind diminished and even disappeared in most areas, although both ritual and entertainment ciwara persisted in the Mande Plateau region into the 1990s and may still exist. Brightly-painted antelopes (Fig. 164) became standard subjects in secular cheko performances by youths that employ masquerades and puppets to entertain young women and the community as a whole. The association of antelope with grace and farming continued, even as its spiritual and specific mythological associations faded.

Older Bamana antelope masquerade crests vary in form and style a great deal, not only from one Bamana region to another, but among artists. Formal typological studies place the vertically-oriented crests (Fig. 165) in the northern Bamana region around the town of Segou. This style has come to typify foreign expectations of ciwara, which have become iconic examples of African art. The male crest is larger, and indeed the performer who wears it is the star performer of the masquerade; the female appears to be present to ensure his recognition as a complete male. Both male and female (and infant male, carried on his mother’s back as a human child would be carried) a human-like nose, much like those found on other Bamana sculptures; the female wears earrings, as many ciwara (but no wild animals) do; some researchers describe the muzzle as bird-like rather than mammalian. The two genders are clearly differentiated, as the penis is prominent. Their upright horns differ slightly, and indeed they are said to represent two separate antelope types (Fig. 166), the male a roan antelope, the female an oryx. Neither image is species-specific nor naturalistic. The heads dwarf the bodies, the legs are short and hoofless, the necks take on a geometric character. Although male roans do indeed have long ears, they have been exaggerated in the carved versions, and the gracefully arching neck is the artist’s creation. They do have manes, but the triangular cut-outs that lighten the mass are pure fancy; while some researchers have stated the resulting zig-zags represent either the antelope’s fits-and-starts path or the passage of the sun, these are no longer general Bamana interpretations, if they ever were. Whereas the actual roan has horns with a clearly backward curve, the carved version’s horns are straight, bending backward at an angle at the top. although this is not inevitable (Fig. 167). While the wooden female crest does have the straight horns of the oryx, she does not otherwise follow its anatomy, and backs her young like a human mother (Fig. 168). Prayers at the outset of the old ritual performances ask Ci Wara the spirit for a bountiful harvest and plenty of new babies, attesting to the association of crop and human fertility.

Horizontal ciwara crests (Fig. 169) originate from the Beledougou region of the western Bamana, who live north of Bamako and the Niger River in Mali. Their construction is very different from the monoxyl carvings of the vertical crests, for they represent a rarity in traditional African sculpture–a carpentered piece that does not come from a coastal area potentially impacted by European approaches. The joint between two pieces of wood always occurs at the neck, where metal staples (or occasionally a metal “collar”) connect them. This is apparently a conceptual rather than a practical choice, for area trees could easily accommodate this size of sculpture. These crests also have diminutive bodies

dominated by head and horns, and are also said to be modeled after roan antelopes. The impressive sweep of the horns, however, turns slightly upward, unlike those of an actual roan. The animal’s tongue is frequently shown, and fine, varied geometric patterns usually cover both head and body. Eyes may be only partially carved, represented instead by inserts of metal studs or beads, and yarn tassels often add textural interest to ears and snout, as do metal, beaded, or shell earrings.

Many horizontal crests incorporate features of other animals, such as a chameleon’s curling tail. Although their tails actually curve downward, artists throughout the continent often portray them this way. Chameleons are often associated with transformation because of their color shifts. Some of these composite animals have curved backs (Fig. 170) that refer to the aardvark (Fig. 171), a clawed animal whose digging abilities mirror those of a champion farmer; the long ears also bear a strong resemblance to those of aardvarks. The textured body may refer to a stylization of the pangolin (Fig. 172),

a scaled mammal that also uses its claws to dig for ants and termites. Other examples may include multiple sets of horns and/or add a human figure (Fig. 173), or stack the head of one species over a second animal (Fig. 174).

The most curious aspect of these horizontal examples is their intentional joinery. Why two pieces of wood? A complex farming/mythological explanation is offered by the Romanian researcher Dominique Zahan: these crests represent an inverted world inspired by plants that flower underground, namely the legumes peanuts and Bambara groundnuts (Vigna subterranea). The border of above and below is marked by the joint, and animals represented above–such as the roan antelope or the goat–are associated with the sun. Those below the join represent the underground realm, and nocturnal digging animals like aardvarks and pangolins. Inverted curling tails and horns? They represent “that one hopes and expects to be able to harvest [groundnuts] easily” (Zahan and Roberts: 2000, p. 42). The point of attachment? Not only does it symbolize the upper and lower aspects of groundnut and peanut growth, it is interpreted as maintaining the balance between paternal and maternal kin in a Bamana region that places greater-

A third set of crests is far more abstract. Its origins may lay in a neighboring group that has influenced the Bamana, in a masquerade similar to ciwara but with separate origins, or to different stylistic choices. Based in the Wassalu region of southern Mali, which borders Guinea and Cote d’Ivoire, this multi-ethnic area composed of Fulani, Malinke, and Bamana mixes apparently impacted the neighboring southern and western Bamana. These crests are called sogoni-kun, and, although they sometimes performed in the fields, their choreography and cloth costumes differentiate them from ciwara. Confusing the matter, however, is the fact that some crests that appear to be ciwara crests are also used in sogoni-kun and bear that name.

These crests often include only a highly schematized indication of an antelope head, often surmounted by multiple sets of horns (Fig. 175). The head often rests on the back of an anteater, and a male or female figure may indicate the “gender” of the paired dancer (Fig. 176).

Additional crest variations are known, some visually aligned to one of the three major forms, others combining horns, figures and animal differences in increasingly abstract modes (Fig. 177).

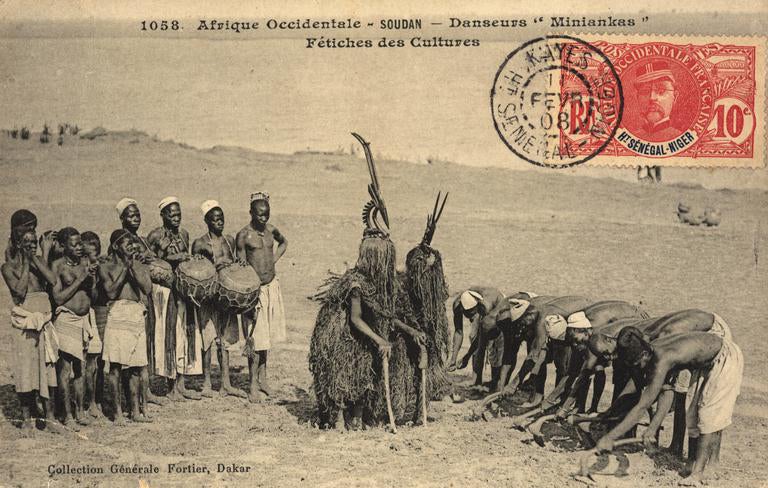

As is the case for some other Bamana masks and practices, antelope crests associated with farming are not necessarily limited to the Bamana. Their neighbors–Mande and non-Mande–use similar crests, examples being found among the Marka, Wassalu, Minianka, the bordering Senufo, and the Maninka of Fouladougou. Even a single image can confuse the issue (Fig. 178), as in the case of this postcard published as Minianka, yet referred to in a 1912 book by a local French official as illustrating an agricultural festival of the Senufo of the Koutiala region. Later publications have used it to illustrate Bamana practices. Many forms of cultural expression cannot neatly be confined by ethnic designations, but they do provide a handy reference point in the absence of

artist’s names and specific provenance, which explains their persistence.

Since the early 20th century, the graceful forms of Bamana ciwara–particular those with vertical orientations–have attracted the attention of Western collectors and artists. Although their use diminished or ceased, outside demand increased, and carvers–both Bamana and other–have matched the export market appetite with tourist art crests that have never seen a field or a performer’s head. For the Bamana, they have become a badge, marking not only their own territory through public sculpture at the gardens of Bamako’s City Hall or locally-produced clothing motifs, but nationally emblazoned as an airline logo (Fig. 179). For those outside the continent, the ciwara have become one of the premier symbols of Africa, one of the few actual African sculptures to grace the Marvel Comics world of Wakanda, a mythical nation (Fig. 180).

Further Reading

de Ganay, Solange. “On a Form of Cicatrization Among the Bambara.” Man 49 (May, 1949): 53-55.

Imperato, Pacal James. “Bambara and Malinke Ton Masquerades.” African Arts 13 (4, 1980): 47-55; 82-87.

Imperato, Pascal James. “The Dance of the Tyi Wara.” African Arts 4 (1, 1970): 9-13; 71-80.

Imperato, Pascal James. “Sogoni Koun.” African Arts 14 (2, 1981): 38-47; 72; 88.

LaGamma, Alisa. Genesis: Ideas of Origin in African Sculpture. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003.

Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington, DC. “Togu Na and Cheko: Change and Continuity in the Art of Mali.” 1989.

Vogel, Susan, ed. For Spirits and Kings: African Art from the Tishman Collection. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1981.

Wooten, Stephen R. “Antelope Headdresses and Champion Farmers: Negotiating Meaning and Identity through the Bamana Ciwara Complex.” African Arts 33 (2, 2000): 18-33; 89-90.

Zahan, Dominique. Antilopes du soleil, Arts et Rites agraires d’Afrique Noire. Vienna: A. Schendl, 1980.

Zahan, Dominique and Allen F. Roberts. “The Two Worlds of Ciwara.” African Arts 33 (2, 2000): 34-45; 90-91.

Animals of the Present: Willie Bester’s The Dogs of War and The Trojan Horse

Willie Bester’s Dogs of War (Fig. 181) is a menacing figure who has torn his lead from any controlling hand. He lopes forward, snarling through his muzzle, his body a conglomeration of metal machine parts, a tin cup, batteries (or dynamite), with a battered but serviceable machine gun mounted on the back. The common steel prevents distractions, urging an examination of the multiple textures that provide the uncared-for look of a true junkyard dog. He is all diagonals, their power and implied activity creating a Terminator-like futuristic effect that spawns anxiety.

The artwork’s name originates from Marc Anthony’s line in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: “Cry ‘Havoc!’, and let slip the dogs of war.” “Havoc” was an actual military order, one that called for complete annihilation. While actual military dogs were used by the Romans, the term also applies to mechanical devices that hold or fasten; “dogs of war” has also come to mean mercenaries. The title does not refer to a declared war; although South Africa had some involvement in the World Wars, the Korean War, and the Namibian War for Independence, its last major military involvement took place internally with the Boer Wars that ended in the early 20th century.

If not a reference to an actual war, is the piece then a commentary on general havoc in South African society? While that layer of meaning may be present, this work is actually an image drawn from an actual event, and the installation this work was a part of scrutinizes the event in multiple ways. In 1998, four years after Nelson Mandela was elected president, some white South African police in a canine training unit set their dogs on illegal immigrants from neighboring countries–and videoed themselves. An investigative television program obtained the tape two years later, showing it to key politicians and broadcasting it; one year later, those involved were sentenced. Bester’s work, produced the year of the convictions, was part of an installation that explored the event in multiple rooms. Its central ensemble, called Who let the dogs out? included a barricaded section through which viewers could become voyeurs of the violent original footage of intent German shepherds, detached police, and terrified immigrants (see the video below; WARNING, it is extremely graphic). The accompanying sculptural group included life-size scrap metal policeman, a dog attacking the victim, and a second policeman with a video camera replacing his head.

The image of the dog took on a great deal of prominence in the apartheid world of South African artists. A potent symbol of police brutality and the will to control, these German shepherds not only appeared in many journalistic photos (Fig. 1820, but also featured in the art of David Koloane–feral, without leashes or handlers–and Norman Catherine–where they were anthropomorphized with human features and police caps. When apartheid ended and Mandela was elected to office a few years later in 1994, South Africa attempted to address its violent past history with a tribunal known as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (1996-1998) chaired by Bishop Desmond Tutu. Its investigation of incidents that took place from 1960-1994 was purgative, and many chose to believe that its confrontations–many broadcast–could be put away. Bester’s Dogs of War and a number of subsequent works continue to rip the scabs off a past that has not vanished. As reviewer Brenda Atkinson wrote in her positive view of the exhibition: “Detractors of Willie Bester’s work are often bewildered by his relentless revisiting of the theme of racial injustice. It’s as if, by refusing to conspire with the soothing discourses of rainbowism and renaissance, he is committing some kind of horrible social faux pas, like revealing an operation scar over dinner party hors d’oeuvres.”

Bester (b. 1956), who grew up under apartheid, neither forgets the ugly past nor its repercussions. He created three versions of another work entitled Trojan Horse. The first two versions were assembled from partially painted recycled materials, stiffly posed and mounted on wheels like pull-toys. These colorful examples were made by 1994, but the third (Fig. 183), created some thirteen years later, has a grimmer, post-industrial look similar to that of Dogs of War, with an automatic weapon again mounted on the animal. Here, too, the animal is more than it seems. Its name does not refer to the Homerian account of Odysseus’s “gift” to the Trojans, but rather to a 1985 police operation in one of Cape Town’s black neighborhoods. There had been anti-apartheid demonstrations there, and the Security and Railway police mounted an operation whereby a truck laden with boxes entered the area, only to have men with automatic weapons appear behind the cartons and fire into the crowd in an incident called the Trojan Horse Massacre. Two children and a young man died, with others wounded. Once more, videotape captured the incident. The perpetrators were investigated years later, in 1988, and thirteen were charged and turned over to the Attorney General of the region, who refused to prosecute. Other efforts at a civil case ended in acquittal. Bester, however, continues to dig up memories of these atrocities from the not-so-distant past. Here he transforms a horse with one leg raised from the typical Western portrayal of a victorious warlord into a vicious reminder of heartless brutality. Other works by Bester can be viewed on the artist’s website, and interviews with the artist can be viewed HERE and HERE.