Chapter 3: Themes in African Art

Chapter 3.8 Portraiture

What Constitutes a Portrait?

“Portrait” seems a straightforward word that is easily categorized, but it is a more flexible category than one might first imagine. Many people would

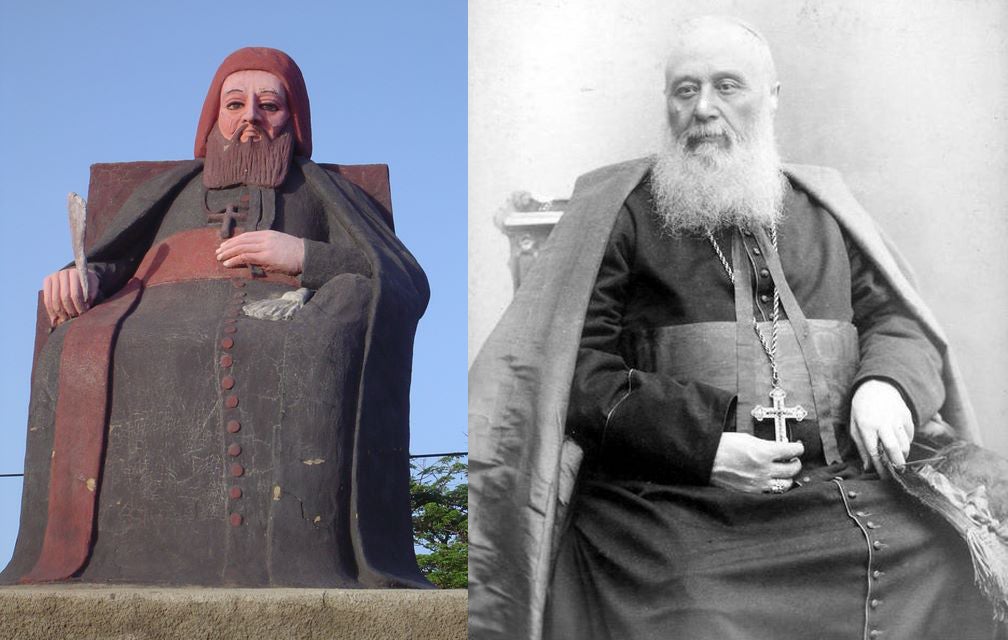

define the term as a likeness, whether in two or three dimensions: something that captures a person’s face, in particular, in a recognizable form, that can serve as a physical surrogate to fix them in memory. While there certainly are African portraits that fit this criterion, most are contemporary works: photographs, paintings, or sculpture. Even these works may not be exact portraits, for photo retouching, generalization, or idealization can mask signs of age or other flaws and details visible in person, as occurred in a Ghanaian statue of Cardinal Lavigerie, founder of the Catholic order of the White Fathers (Fig. 458). The sculptor regrew and colored the subject’s hair, shifting his position in the source photograph to a frontal placement that affords more dignity.

If we consider “portrait” more broadly as an aide-memoire, something that we recognize as a stand-in for a particular person, the image does not need to replicate an individual’s appearance in full–it is enough that the viewer conjures them up when viewing the work. Numerous traditional artworks do this through a variety of techniques: the naming (whether verbal or not) of an object; a concentration on certain traits evoking the individual that do not include the facial features, such as hairstyle, facial marks, or clothing associated with a particular social role; an object or emblem that is so closely identified with an individual that it can stand in for them; or a generic-looking abstraction that, through physical proximity to grave or ancestral altar, assumes the role of the “face” of the deceased.

Other possibilities exist. Even in contemporary terms, the photo of an empty room may convey the personality of an individual, as can a non-objective combination of color, line, and shape. However, even when a work is figurative, it is not necessarily a portrait. It may instead be a general image of male or female with no intention to be identifiable with a specific person. With that in mind, let’s consider a range of portrait types–some traditional, some contemporary–both briefly and as case studies.

A Range of Traditional Portrait Variations

We’ve encountered certain portrait types earlier in this book, many related to commemoration. Both Akan terracotta memorial heads (mma) and figures, for example, and Yoruba ibeji figures, memorialize specific individuals, yet their physical resemblance to the individual may be extremely limited. In the case of the Akan, only royals were represented in this way (Fig. 459), their portraits displayed at their funeral. The works themselves ranged from extremely flat, very stylized heads to more rounded and fairly naturalistic examples, often from the same places and even archaeologically found at the same level. Though the best portrayals were attributed to artists who knew the deceased, observed them on their deathbed, and summoned their image when gazing into a bowl filled with liquid, they were neither intended to fully resemble an individual or simply idealized them. Resemblance might be confined to a hairstyle, and idealism not only resulted in ephebism, but in the broad flattened forehead, pronounced eye sockets, lined neck, and gleaming skin (attained by the use of mica dust or burnishing) that the Akan favor in life. However, another practice–that of deception–demonstrates that, for the Akan, nothing could be more of a portrait. Deception of harmful spirits is conducted among newborns, and also occurs with the memorial heads–misleading facial marks might be temporarily applied to trick spiritual malefactors from recognizing the individual and deflecting evil.

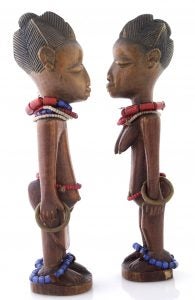

Despite Yoruba disinterest in the specific physiognomies or body types of deceased twins, close identification between an ibeji figure (Fig. 460) and the individual it represents remain. Research among the Yoruba, for example, found that Yoruba mothers of deceased twins were unable to dispassionately discuss the appearance of the figures that represented them. They so closely identified the figures with their children–even years after their death–that an objective evaluation of the works as carvings was impossible for them. The figures idealize the infants, not only in terms of hairstyles and facial features, but by turning them into full adults, something that never occurred in their worldly lives.

Many African portraits bear generic visages, but bear other markers that indicate they are portraits of a specific individual, as well as supernatural markers that do the same. The Bushoong rulers of the Kuba Kingdom, for example, had themselves commemorated by large wooden figures (Fig. 461) that were normally kept in a royal shrine with powerful medicines, and were rubbed with oil to keep them revitalized. Considered his double, it offered both protection and fertility, and was kept in his wives’ quarter, placed near a wife about to give birth. After a ruler’s death, a new monarch would sleep in its presence during his ascent to the throne; former wives would take charge of the sculpture afterward. The ndops‘ facial features and hairlines were consistent and impassively expressionless, as a monarch was expected to demonstrate complete self-control in public. The figures are fleshy, speaking to the king’s prosperity, good living, and health. Each portrait sits on the low box throne and wears the projecting beaded crown, the shoulder rings, the crossed cowrie bands that form key components of the far more complex royal attire; all bear a ceremonial knife in the right hand. What individualized these portraits was the key symbol (ibol) placed in front of the ruler and associated with him. For example, the mancala game introduced by the first monarch appears on his statue and exemplifies the life of ease and leisure time his reign produced.

Similarly, the leaders of Kalabari Ijo trading houses are remembered in portraits not by their life-like facial features, but through the masquerade

associated with their house. Two of the surviving examples (Fig. 462) depict the heads of rival firms; these screens served as shrines in trading company meeting houses, where these important corporate ancestors were sacrificed to weekly for the firm’s continued success. These shrines both left the region in the early 20th century when a zealous local Christian threatened their destruction; others continued to be made in the region and stand a century later. Both of these examples are shown in the seated pose of a dignitary, flanked by a hieratically-scaled entourage that reinforces their importance. Their facial features are simplified and generic, the bared teeth a sign of male aggression.

All were probably dressed originally, as the figures in the right-hand example are, and emblems of power and attached heads probably decorated both as well. It is, however, the headdress of the leader that symbolically identified him, for it represents the masquerade figure he danced when alive. The masqueraders themselves covered their faces and chests with cloth; women and children were meant to believe they were otherworldly water spirits. Because the meeting houses were off-limits to the uninitiated, the screens could reveal the human identities of those trading house leaders who wore them, their secrets ensured. At left, the business leader wears the feathered and tasseled headpiece of the alagba masquerade, which several houses perform. He probably originally bore the alagba masquerade’s knife in his left hand, holding a carved ivory tusk in his right. At right, the leader wears the European ship headdress for the masquerade known as bekinarusibi (“white man’s ship on head”), and holds a staff and decorated tusk. Both of these masquerades are still performed and are even commemorated by contemporary artists.

Sokari Douglas Camp, a British-trained Kalabari artist, has created a series of welded-steel water spirit figures, including that of bekinarusibi (Fig. 463) and alagba. Although both works are abstractly treated, Camp’s work is far more naturalistic in its head-to-body proportions, while the ancestral screen emphasizes the figures’ heads. The Kalabari Ijo name for these pieces, duein fubara, is translated as “foreheads of the dead,” the foreheads of the living being associated with their guiding spiritual force. Carved masks and ancestral screens both are both intended to give the living some control over powerful spiritual forces, compelling or persuading them to favor those who honor them through sacrifice and entreaties, serving as communicative tools.

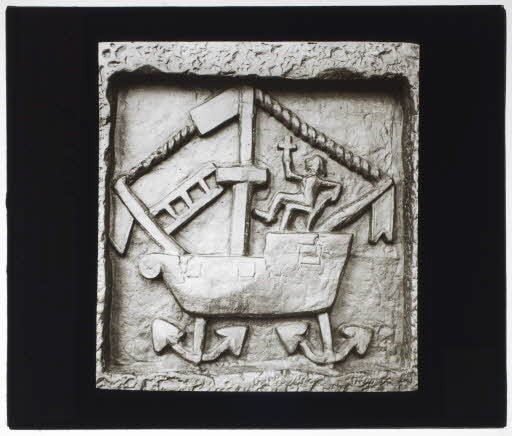

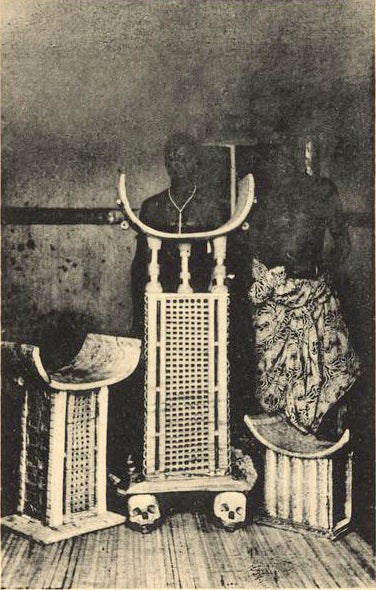

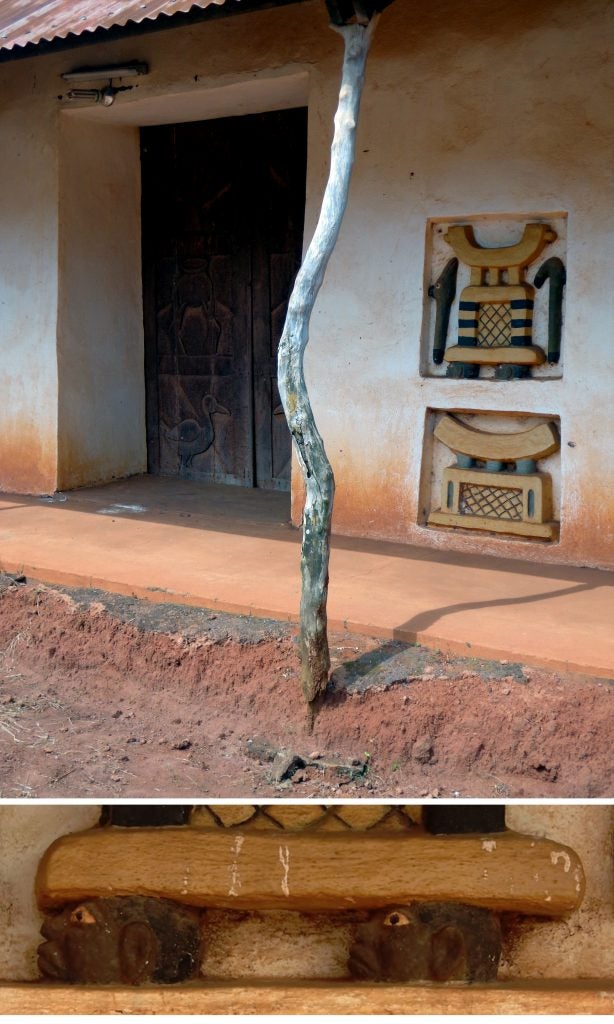

Symbolic portraits can go much further than representations of symbolic masks on the head of abstracted figures. For the Fon of Dahomey Kingdom in today’s Benin Republic, each king had multiple visual badges that represented him on banners, parasols, or even architecture. These might not even include human figures; rather, they represented powerful proverbial names he acquired during divination early in life or specific events that occurred in their reign. The monarch Agadja (reigned 1718-1740, for example, was represented by a foreign ship (Fig. 464). Due to his conquests of the coastal states, he became the first Fon ruler to maintain direct trade with

Europeans. While some 19th-century monarchs were represented by large anthropomorphic sculptures that referred to their emblems (see Chapter 2.5), non-figurative objects also served as conceptual portraits–namely, their actual thrones (Fig. 465). These had attendant priests who held parasols over them when they were periodically on public display, and some were depicted on buildings within the royal palace compound. Although Ghezo’s actual throne rested on the skulls of his enemies, their modeled clay portrayals showed it on freshly-severed heads (Fig. 466), a reminder of his power and prowess.

Some traditional portraits are less symbolic. While not naturalistic, they include scarifications and other features that can be personally identified with the subject. Baule masquerades, for example, include several types of sacred performances, as well as some whose expression is directed toward entertainment. These feature portrait masks (mblo) of both males (Fig. 467) and females (Fig. 468)–often acclaimed dancers–though both are danced by men. Women’s portraits are more common, and are usually commissioned by spouses or male relatives. Such masks are usually danced by a family member with the portrait’s subject participating as well. Even after infirmity or death make the latter impossible, other family members may step in to continue the performance across generations. The performance is an occasion of a dramatic reveal; the mblo step out concealed by a cloth enclosure, revealed briefly in an entrancing blitz of beautiful cloth, graceful features, and superior dancing before being wrapped and stored in the dancers’ room until another occasion warrants their appearance. While these Baule masks are not spiritual in nature, their performance when important visitors arrive, on holidays, and at (mostly

female) funerals contributes to the social cement holding members of the community together.

Among the Dan of Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire, carved portrait figures were prestigious representations of a favored wife of a wealthy man, and were named after her. Upon receiving the commissioned sculptures, the patron would host a party to display the work to friends and family, for it further enhanced his reputation and status within society. At subsequent parties, the work would be displayed or shown to selected guests privately for a small fee. They are no longer being made for this purpose, and seem to have been a phenomenon of the late 19th/early 20th century.

The works (Fig. 469) are considered portraits because they replicate the cosmetic scarification patterns of an individual’s body, as well as ethnic facial markings, but Dan idealization of female beauty means they all usually have finely braided hair, a long creased neck, a high forehead, full lips, kaolin makeup in the eye area, a sharp chin, lowered lids, and the sharpened teeth that were once fashionable, their appearance very like the masks that represent the graceful deangle masks. Many have full breasts–their shapes meant to be personally identifiable as well as a sign of fecundity; others bear proof of fertility through a child tied to the back. The figures are shown standing; although many are now nude, they originally wore loincloths made from hand-woven textiles (Fig. 470). Occasionally male figures or male-female couples were commissioned.

One of the most acclaimed Dan sculptors of the early 20th century–Zlan/Sra–was actually from the neighboring ethnic group, but was sought out for his portrait figures (Fig. 471) and other carvings by Dan, Wee, and Mano clients in both Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire. One of his numerous wives, Sonzlanwon, accompanied him when he traveled for commissions. She is remembered for not only plaiting the intricate raffia coiffures for his figures, but for actually blocking out his carvings for him or completing the whole figure herself. This was a stunning exception to the general rule against African women carving; the artist had many male apprentices during his lifetime, and the Dan, in general, prohibit women from carving, stating infertility will be the result. Zlan himself is said to have appeared in a dream to one of his nieces who had taken up wood sculpting, warning her of the consequences. She ceased, resuming only after she had borne all the children she intended to have, though her work is now done clandestinely.

Dan women sometimes commissioned their own portraits, though as finials of oversized spoons (Fig. 472) rather than standing figures. Again, only a wealthy woman would do so–and only upon public acclamation as a woman of outstanding generosity, the recipient of a village ward’s title (wunkirle–“woman that acts at feasts”) that recognizes her superior actions. As one who feeds initiates, farmers preparing the fields, those attending major events, and guests, she is identified at public celebrations by carrying her large spoon, accompanied by an entourage. Together they distribute rice, coins, or candies to the gathered crowd. Her spoon, however, is not a mere prestige object like the portraits men commission. Instead, it–like Dan masks–is considered the abode of a spirit who cooperates with the woman to help her achieve, and thus sacrifices are made to dedicate the object. It has its own name; it is not named after the owner. Such spoons do not always bear facial portraits, however; they may instead show muscular, capable legs, ram or other animal heads, hands, or abstract elements. Most common are the portraits of the spoons’ original owner, whom the activating spirit sought out as a favored associate. When a wunkirle decides to retire, she chooses her successor and passes the ladle to her, so a wunkirle may actually be using a ladle that bears her predecessor’s portrait, rather than her own.

Photographs and their Impact

The impact of African exposure to photography–which in some parts of the continent was felt within a decade of its invention–has been extensive. Large framed portraits are a mainstay of interiors in many countries (Fig. 473), and are the products of photo studios that continue to grow in number. They are the focus of contemporary obituaries, and often carried in funerary processions or displayed at funerals. As Western collectors and scholars grow increasingly interested in the history of African photography, the work of photographers who once had humble neighborhood operations, such as Malian Seydou Keita, has been promoted to international status (see HERE). As such, most African studio photographs follow many of the precepts of traditional art: they focus on human beings rather than, for example, landscapes and they

generally are formal in pose and facial expression.

Photographs are printed on materials other than paper. Factory-made commercial cotton textiles, often wax prints that employ resist techniques often employ portraits of individuals within medallions, as well as drawn motifs and patterns (Fig. 474). These usually commemorate anniversaries of various kinds, birthdays, or funerals, but can also mark state visits. Although special commissions, they are reasonably priced and often purchased for groups to sew as “uniforms” for specific occasions where they wish to express visual solidarity.

Photographs have also impacted other mediums. At the turn of the 20th century, the British had colonized Nigeria, and both military and civil service offices in Lagos included photographs of the queen–much as such offices today include framed photos of state governors and the head-of-state. They also included newspapers from Britain, many of which published photos and illustrations that included her. In southwest Nigeria, particularly in Lagos and in Abeokuta (49 miles away) some artists began producing portable wooden sculptures of the monarch (Fig. 475). While these tended to end up in European hands and were later disseminated to museum collections, their original patrons and artists may have been a specialized group of Sierra Leoneans resident in Nigeria, there known as Saros. These individuals were the offspring of enslaved Yoruba that had been intercepted by the British during the 19th-century slave trade before trans-Atlantic shipment. After the British rescued Yoruba, Kongo, and individuals from other African groups stowed upon slave ships, they deposited them in their West African colony of Sierra Leone, already the new “homeland” of poor blacks rounded up in London, Jamaican rebels who had been exiled to Nova Scotia, and black Loyalists who had fought with the British during the American Revolution. Those Sierra Leoneans with Yoruba origins were educated in British schools, many became Christians (even as prominent missionaries), and their lifestyle was frequently

Europeanized, to greater and lesser degrees. Some of these individuals remembered their families’ origins, and, as British colonization spread and steamships permitted easy travel between colonies, many moved back to those parts of Nigeria under British control.

Familiarity with British images of the monarch (Fig. 476), whether on souvenirs or in printed form, inspired numerous images based more on photographic likeness than on generic physiognomy. Victoria’s full cheeks and heavy lids are personalized, even as her body type ranges from slim to thick in various examples, and her head-to-body proportions retain an emphasis on the head. Details of her clothing are carefully delineated, from her hanging sleeve to folded fan to drop earrings. Although numerous depictions focus on the queen’s small coronet and Honiton bobbin lace veil, this artist provided her with a larger crown and concentrated on the rosette furbelows of her bodice. Familiar with European female dress because many church-going Saro women had adopted it, this artist and others provided Victoria with shoes, unseen unless the sculpture is upended. Such figures confirmed the owners’ identity as members of the overseas British Empire and under its monarch’s protection. The scholarly suggestion that these sculptures may have particularly resonated with female patrons seems sound; they were often independently wealthy traders who valued the freedom of movement British overlordship provided.

A later colonial work (Fig. 477), carved some decades after the monarch’s 1901 death, shows more of an awareness of earlier sculptures than the photographic model. The Yoruba sculptor Thomas Onajeje Odulate has used employed his consistent style to create a generic figure, individualized only by her carved name and certain costume details–her lace veil, high-status headgear that is neither coronet nor standard crown, and fan. Inventive departures, such as the sculpture’s bust-length, the high collar, and application of officer’s epaulets, marry with certain Yoruba stylistic traits, such as oversized eyes. Odulate’s works were sold as souvenirs to Britons living in Lagos, and usually depict the colonialists, along with some of their African employees. This prolific artist was already working in Lagos as an

artist by the early 20th century, and this may have been part of a personal revival of foreign figurative types he had seen at the beginning of his career.

Many vernacular or urban painters have been heavily influenced by photographs, particularly those seen in billboards and other print advertisements. The visible use of light and shadow to make a flat photograph look three-dimensional could be copied in pencil or with paint, acting as a kind of portable instruction in realism. This particular importance of the face in capturing a likeness could be taken from readily available newspaper images, even when the artist never met the subject. Likeness can be essential; depending on the meaning of the work, identifiability of the subject can be critical, and may be reinforced by text.

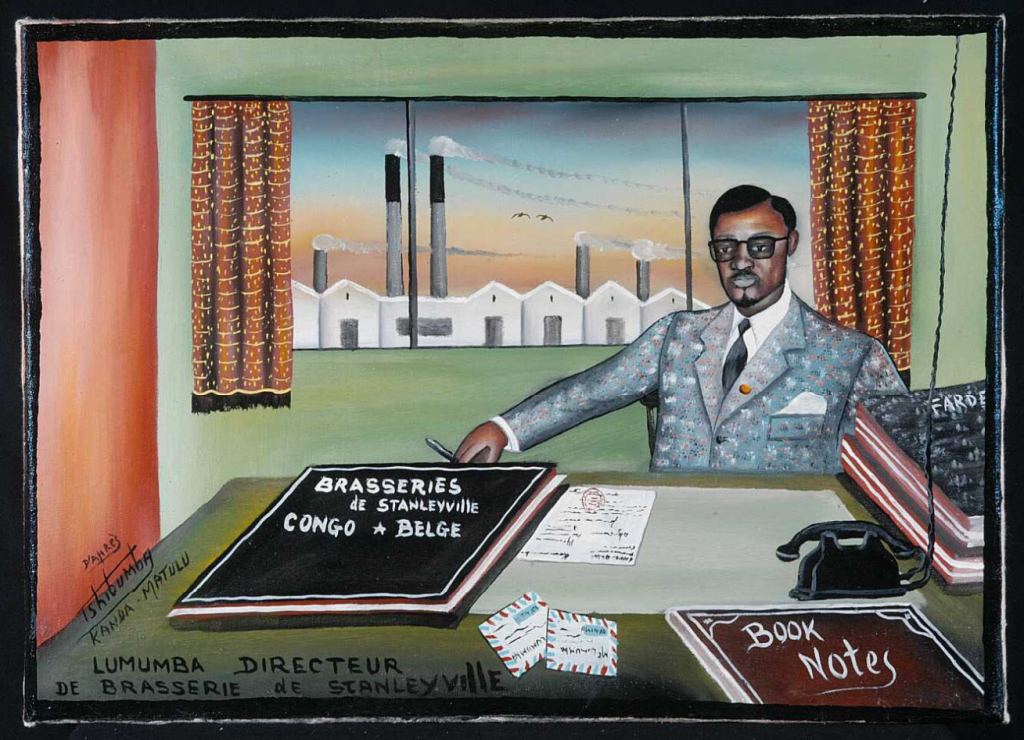

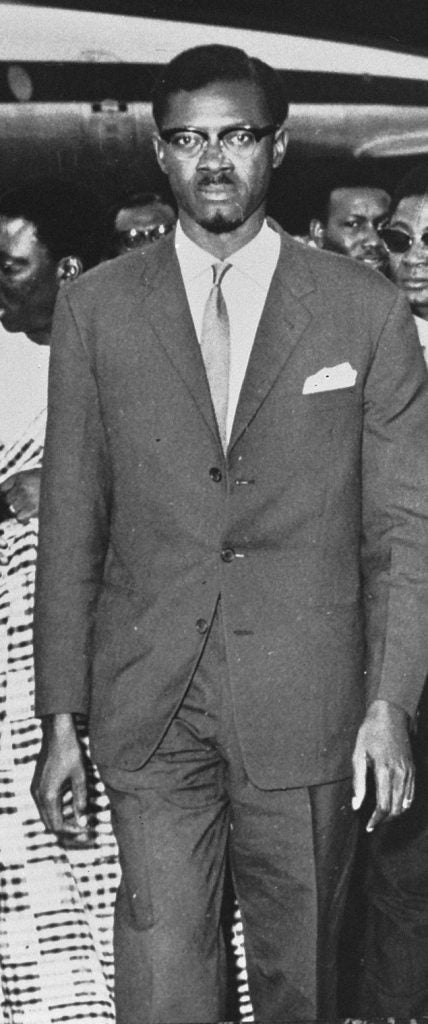

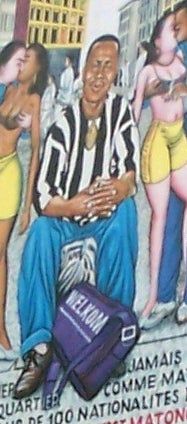

The artist Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, who was based in Lubumbashi (then Élisabethville), Democratic Republic of Congo, created a series of 18 paintings that examined Patrice Lumumba’s place in the history of his country. The narrative of these works, made in the 1970s, begins before Lumumba’s political career took off. One shows Lumumba in 1957-1958 as a brewery director after an earlier stint as a salesman and postal service employee (Fig. 478). Despite the painting’s reference to Stanleyville, the brewery was actually in Léopoldville.

Of greater importance is the recognizable depiction of Lumumba (Fig. 479), and the environment that underlines his prosperity, education, and modernity, portraiture techniques with a long history in Europe, but absent in older African art. Aspects of Lumumba’s traits are generated by the window view of the factory itself, his stylish suit, the telephone and letters that indicate his constant communication with other important figures, and the ledgers and books (one in a foreign language, demonstrating his cosmopolitanism) that cover his desk. He first became an independence leader and then the DRC’s first prime minister–in office for a little over two months before an army rebellion

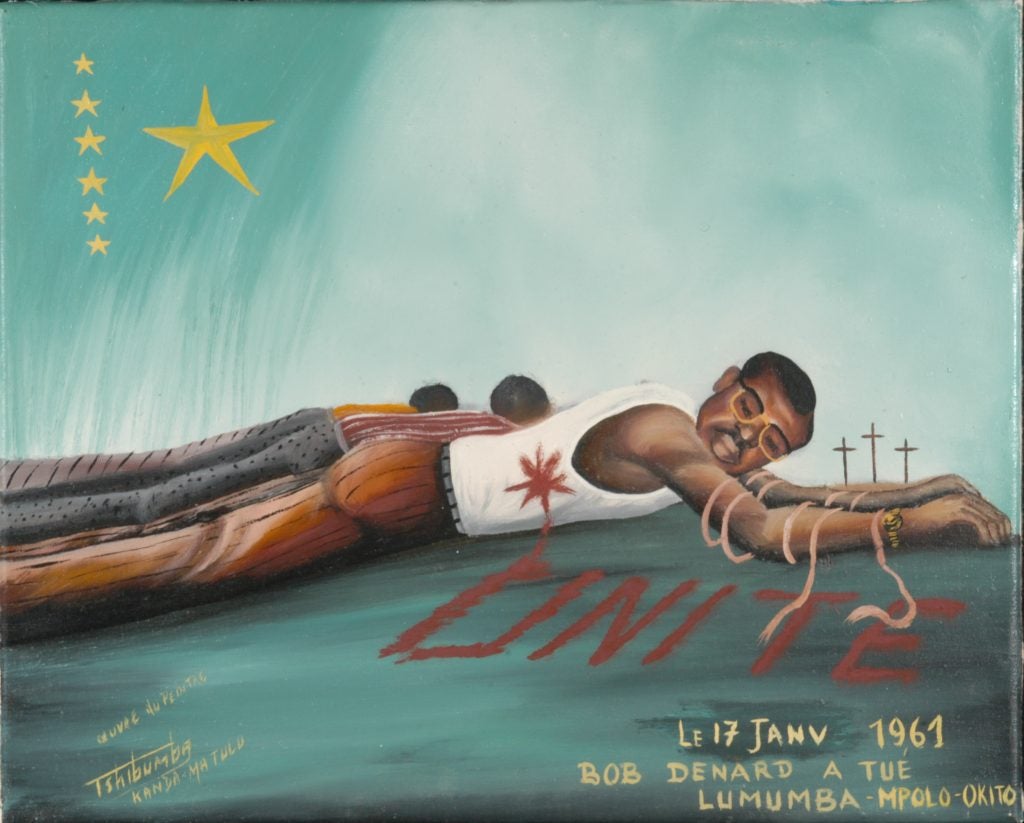

and a secessionist movement involving natural resources caused the country’s president to dismiss him and six of his ministers. With foreign involvement and support, Lumumba’s former chief-of-staff, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, engineered Lumumba’s death as the latter planned to create a new government, and became head-of-state himself from 1965 to 1997. Tshibumba Kanda Matulu was not present at the execution, nor were there any photos Lumumba’s secret death by military firing squad alongside Maurice Mpolo, who was to be his Minister of Defence, and his former Senate Vice-President Joseph Okito. The artist turns Lumumba’s face to the viewer to verify his identity (Fig. 480), including his trademark razor part, glasses, and facial hair. Through the crosses in the background and the wound in Lumumba’s side, the artist expressed widely-held views that Lumumba was a martyr to the cause of his country’s unity, underlined by the word itself, spelled out in blood. The painter’s political convictions and visual documentation are thought to have led to his own demise; under Mobutu’s rule, he was last seen in 1981, believed to be the victim of Mobutu’s ruthless silencing of verbal and visual criticism. Each of the images draws attention to a particular incident in Lumumba’s life, and each is a portrait of the man at a specific moment, reimagined by the artist.

Contemporary portraiture includes a variation whose origins in Western art represent a radical change of direction in Africa: the self-portrait. No patron would have paid for an artist’s image in the past; even now, that cost is likely borne by a Western collector or museum. Still, the self-portrait permits not only an intimate capture of physical appearance (Fig. 481), but also allows a psychological self-study. Even when wry or confessional, these revelatory images expose their subject. One of the most consistent producers of the self-portrait is the vernacular painter Chéri Samba, whose earliest works include examples in fashionable sportswear surrounded by an autobiographical text, in a stylish sitting room (here), or caught between rival who want his paintings (here). He has explored infidelity and questions of love (here), interrogated his own

place in the world of African and modern art (here), depicted himself consulting a ritual specialist after experiencing difficulties, and tracked his appearance after six decades without airbrushing his growing wrinkles and receding hairline (here). Together, his self-portraits create a fuller picture of the man than any other African artist.

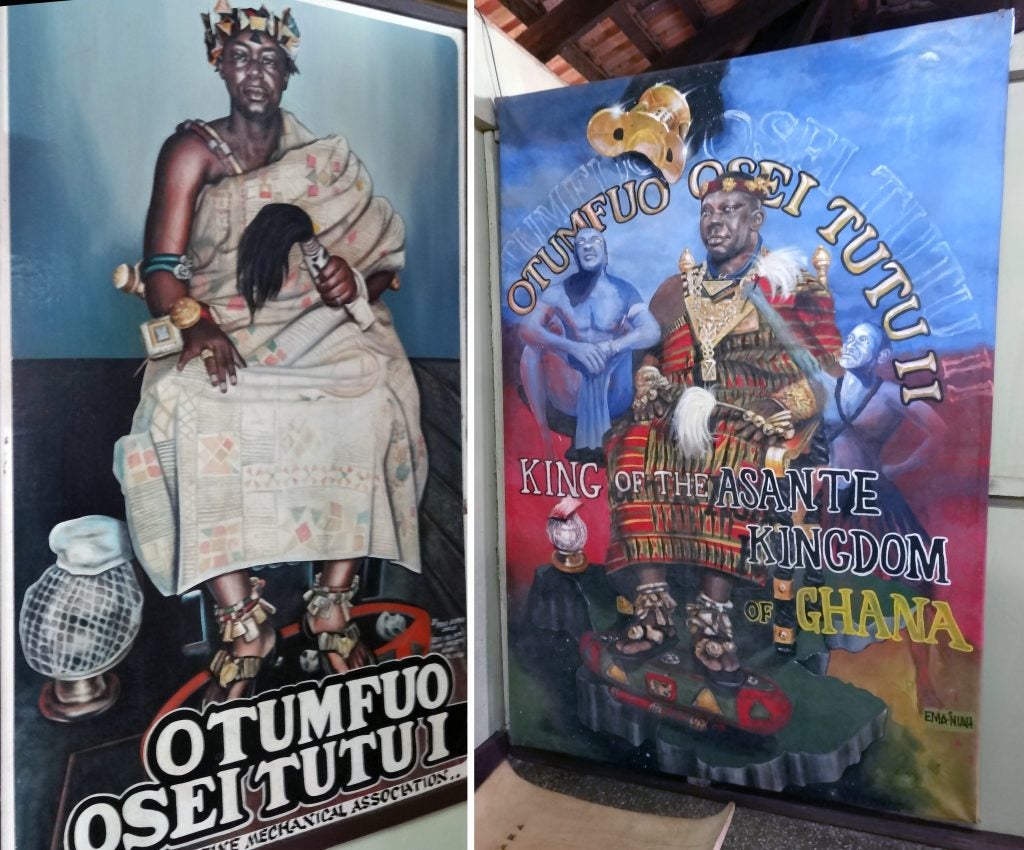

Sometimes images can appear to be realistic likenesses, yet they remain imaginative recreations of historical figures whose facial features are unknown. Two contemporary paintings depict two Asantehenes, the monarch who ruled Ghana’s Asante Kingdom (Fig. 482). One is currently ruling, having ascended the throne in 1999. The artist may have seen him at a public event, and most certainly has viewed him on television and/or newspapers. As his physiognomy is well-known, a likeness in this contemporary mode is both expected and attainable. His earlier namesake, the first ruler of a unified state that incorporated other Akan, ruled long before photography and his facial features are unknown. Using an unknown model, the painter has given him a plausible face, the portrait made complete by the addition of jewelry, prestige cloth, footrest and crown suitable to the monarch. In both cases, the name of the monarch is added to remove any doubt about the subject being depicted.

In the Cameroon Grassfields, carved figures represented monarchs and their wives, and were kept in the treasury to be brought out and admired on state occasions (Fig. 483). These were fairly abstract works, identified with their subject through naming rather than facial recognition. But colonizers and missionaries brought cameras to the area, and

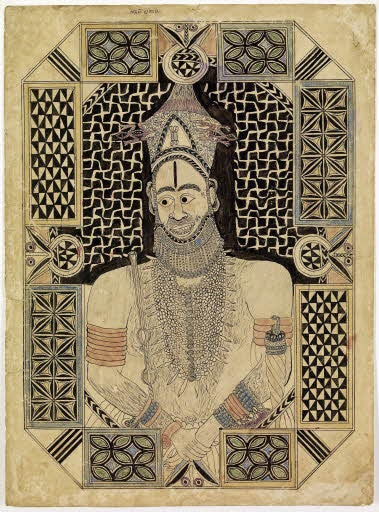

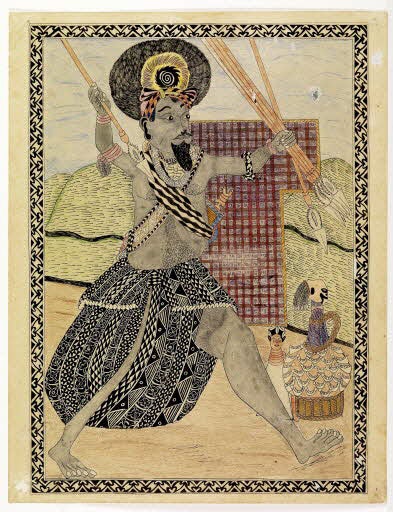

both rulers and citizens became the objects of their gaze and documentation. In the Bamum kingdom of Fumban, Sultan Njoya (ruled ca. 1886-1933)–himself the subject of numerous photographs (Fig. 484)–encouraged a new direction in portraiture, which his cousin Ibrahim Njoya led. These portraits on paper documented past rulers and famous courtiers. Like the Asante rulers, recent ones could be likenesses, but rulers who lived in the more distant past were only verbally described, required the artist to construct an appearance. Ibrahim Njoya’s half-length portrait of one of his ancestors, the monarch Mbuembue (Fig. 485), shows him with a slightly-tilted head, looking away from the viewer. Many of the markers of his rank are like those found on

older carvings that replicate actual objects, such as his beaded “beard” and crown, as well as his jewelry, but his head-to-body proportions are natural, unlike earlier figures. His facial features are fairly naturalistic, but there is no interest in shading in order to increase a three-dimensional effect, like that of a photograph. Instead, flatness is emphasized through the screen-like devices that surround the monarch. Their strong graphic patterns mimic designs and symbols found on royal cloths (ndop) and woodcarvings; one, the double-headed snake, is particularly associated with Mbuembue. While these framing devices have been compared to European photograph frames, the latter generally bear one consistent pattern rather than an assortment, and they do not intrude on the image itself. Instead,

here it seems almost as if the ruler is peering out from a screened window frame.

The popularity of Ibrahim Njoya’s drawings led to a school of followers and copyists, extending into the second half of the twentieth century. Many of these have expanded their repertoire of subjects and included action scenes (Fig. 486). This work contains environmental references, something not found in traditional work. Though proportion and anatomy may not be completely accurate, realistic representation is again attempted, even though both of these portraits depict a long-dead ruler whose appearance is known only through verbal description. Multiple diagonals reinforce a sense of action, the warrior filling a composition that is edged with a frame-like border. Symbols reinforce the figure’s identity; the ndop cloth (Fig. 487) shows he belongs to the royal family, while the calabash bottle decorated with enemies’ jaws (Fig. 488) emphasizes his expertise and valor as a warrior.

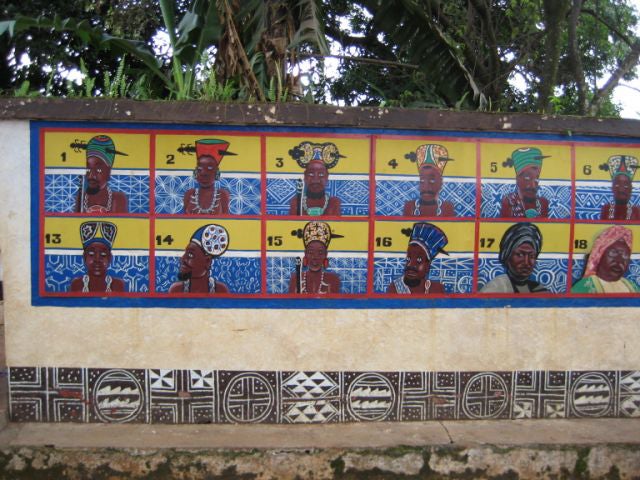

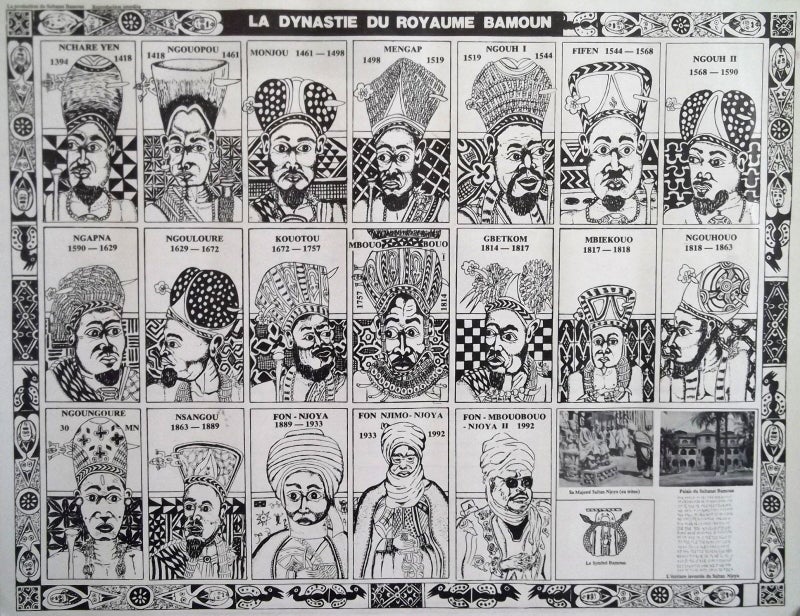

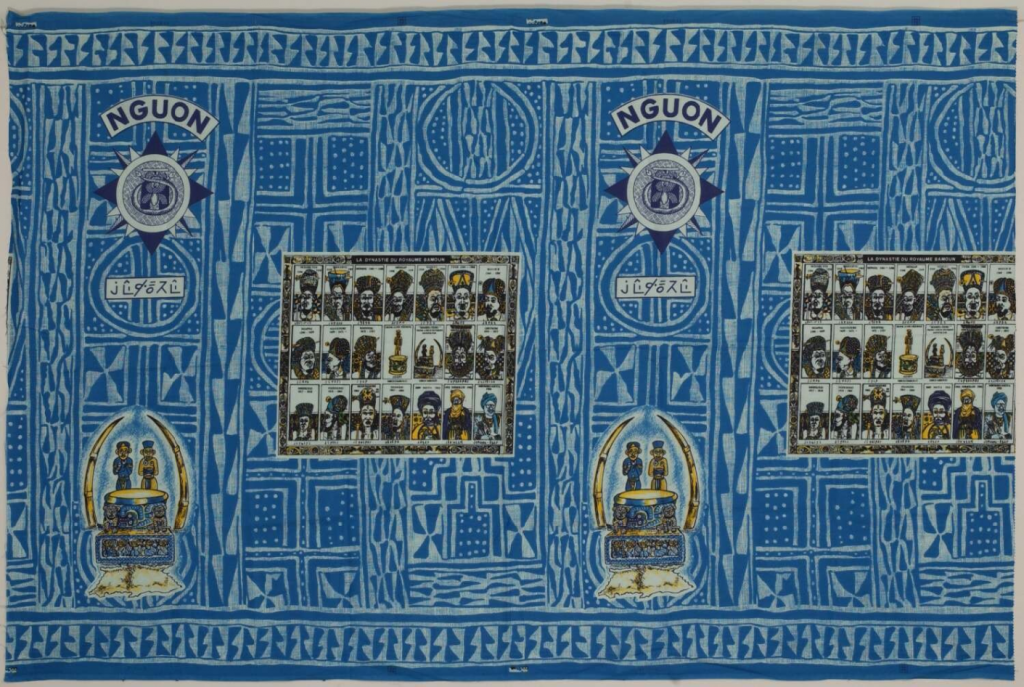

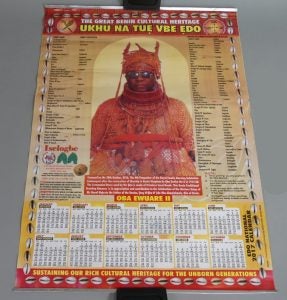

The local popularity of historical figures’ representations has continued, though not always in identical forms. Foumban’s palace complex includes an outer cement wall that bears the rulers’ images bordered by painted ndop motifs (Fig. 489). Mass-produced posters that depict of all of Foumban’s rulers (Fig. 490) also boost citizen’s pride and promote a unified historical record. Similar serial portraits offer a more public way for individuals to show their pride. They can wear a printed cloth bearing former monarchs’ portraits (Fig. 491), against a mechanically-reproduced ndop cloth background that also includes motifs of Njoya’s throne, lettering in the alphabet he created, and other symbols.

At times what seems to be clearly a portrait is not really a portrait at all, and may instead constitute a complex examination of history and identity. The

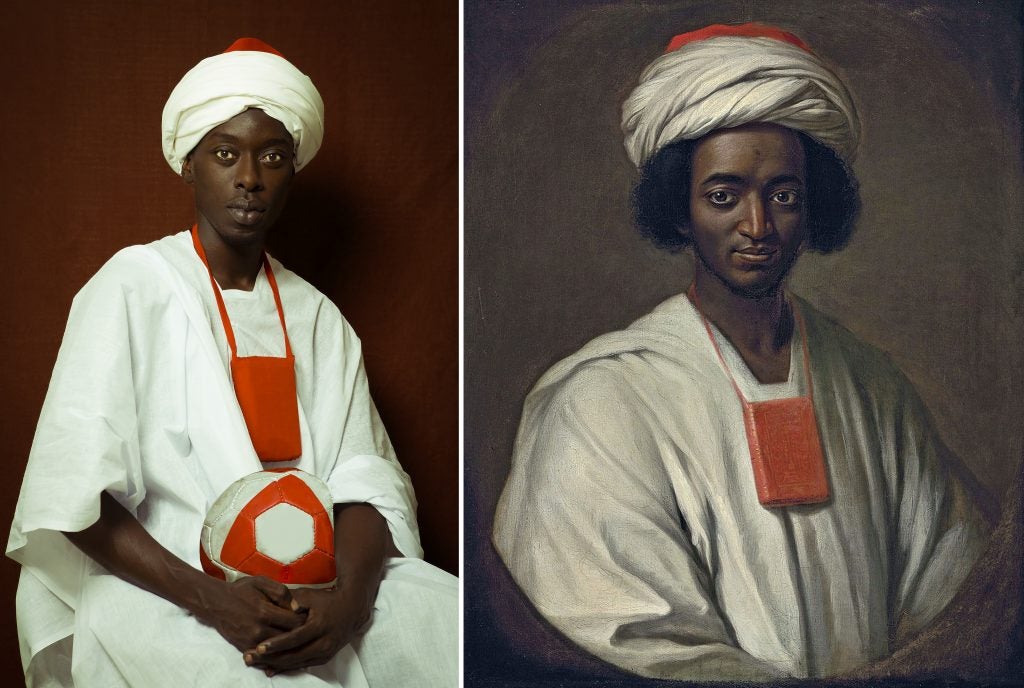

artist Omar Victor Diop, a Senegalese photographer who began his career in fashion photography, has created a series of such works entitled “Project Diaspora.” Its individual components show Diop himself in historical attire, mimicking the composition and poses of African figures in European painted portraits, but he acts as a consistent everyman, rather than showcasing his own appearance or personality. In a dozen-and-a-half works, he considers displaced Africans past and present, the former including figures from the 16th-19th centuries, such as St. Benedict, Juan de Pareja, Frederick Douglass, and others. While some were born in the Americas, most were from Africa but transported to Europe, the New World, or India, then commemorated by artists there. One of the works puts him in the guise of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo, a Fulani prince from present-day Senegal who was captured while traveling, shipped to the United States and enslaved in Maryland (Fig. 492). His literacy in Arabic and a series of letters written on his behalf saw him released from bondage, taken to Britain, and formally given his freedom. He dictated his autobiography, interacted with members of London’s aristocracy, worked with the British Museum on their Arabic manuscript collection, and returned first to Gambia and then home. Rather than merely drawing attention to the historical figure and his life through a reenaction, Diop shows Ayuba holding a soccer ball, an accessory consistent with other photos in the series, their subjects clad in goalies’ gloves, clutching a referee’s whistle, or carrying soccer boots, trophies, or duffle bags. By connecting these historical figures to contemporary soccer players working for clubs throughout the west, he highlights the dual worlds for Africans and their descendants in all periods: while some may be adulated for their skills and accomplishments, racism can snake out and overturn any sense of security or comfort they might feel in adoptive lands in the blink of an eye.

Interview with Omar Victor Diop.

Further Reading

Adams, Monni. “18th Century Kuba King Figures.” African Arts 21 (3, 1988): 32-38; 88.

Anderson, Martha G. “Ancestor memorial screen (duein fubara): Kalabari Ijo peoples, Nigeria.” In William A. Fagaly, ed. Ancestors of Congo Square: African art in the New Orleans Museum of Art, pp. 214-215. New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art, 2011.

Barley, Nigel. Foreheads of the dead: an anthropological view of Kalabari ancestral screens. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988.

Blier, Suzanne Preston. African vodun: art, psychology, and power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Blier, Suzanne Preston. “King Glèlè of Danhomè. Part one, Divination portraits of a lion king and man of iron.” African Arts 23 (4, 1990): 42-53; 93-94.

Blier, Suzanne Preston. “King Glele of Danhomé. Part two, Dynasty and destiny.” African Arts 24 (1, 1991): 44-55; 101-103.

Blier, Suzanne Preston. The Royal Arts of Africa: The Majesty of Form. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998.

Borgatti, Jean M. and Richard Brilliant. Likeness and beyond: portraits from Africa and the world. New York: Center for African Art, 1990.

Cameron, Elisabeth L. “Coming to Terms with Heritage: Kuba Ndop and the Art School of Nsheng.” African Arts 45 (3, 2012): 28-41.

Claessens, Bruno. “Prestigious ladles: spoons of the Dan.” In Marla Maples, ed. African art from the Leslie Sacks collection: refined eye, passionate heart, pp. 248-249; 293; 295; 297; 299; 313. Milan: Skira, 2013.

Cornet, Joseph. Art Royal Kuba. Milan: Edizioni Sipiel, 1982.

Diop, Omar Victor. “Project Diaspora.”

Donner, Etta Becker. Hinterland Liberia. London: Blackie and Sons, 1939.

Drewal, Margaret Thompson. “Portraiture and the construction of reality in Yorubaland and beyond.” African Arts 23 (3, 1990): 40-49; 101-102.

Faber, Paul. The dramatic history of the Congo as painted by Tshibumba Kanda Matulu. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, 2004.

Fabian, Johannes. Remembering the present: Painting and popular history in Zaire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Fischer, Eberhard. African masters: art from the Ivory Coast. Zurich: Museum Rietberg: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2014.

Fischer, Eberhard. “Self-portraits, portraits, and copies among the Dan: the creative process of traditional African mask carvers.” In Christopher D. Roy, ed. Iowa Studies in African Art I, pp. 5-28. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 1984.

Fischer, Eberhard and Hans Himmelheber. The Arts of the Dan in West Africa. Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 1984.

Fischer, Eberhard and Hans Himmelheber. “Spoons of the Dan (Liberia/Ivory Coast).” In Lorenz Homberger, ed. Spoons in African art: cooking-serving-eating-emblems of abundance, pp. 28-40. Zürich: Museum Rietberg, 1991.

Gilbert, Michelle. “Akan Terracotta Heads: Gods or Ancestors?” African Arts 22 (4, 1989): 34-43; 85-86.

Grootaers, Jan-Lodewijk and Alexander Bortolot, eds. Visions from the Forests: The Art of Liberia and Sierra Leone. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2014.

Johnson, Barbara C. Four Dan Sculptors: Continuity and Change. San Francisco: The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986.

Kingdon, Zachary. “The queen as an Aku woman?: reassessing “Yoruba“ Queen Victoria portrait figures.” African Arts 47 (3, 2014): 8-23.

LaGamma, Alisa. Heroic Africans: legendary leaders, iconic sculptures. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.

Loumpet-Galitzine, Alexandra. “Ibrahim Njoya (c. 1890-1966): master of Bamoun drawing.” In N’Goné Fall and Jean Loup Pivin, eds. Anthology of African art: the twentieth century, pp. 102-105. New York: D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, 2002.

Loupet-Galitzine, Alexandra. “Reconsidering patrimonialization in the Bamun Kingdom: heritage, image, and politics from 1906 to the present.” African Arts 49 (2, 2016): 68-81.

Piqué, Francesca and Leslie H. Rainer. Palace Sculptures of Abomey: History Told on Walls. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute and the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1999.

Preston, George Nelson. “People Making Portraits Making People Living Icons of the Akan.” African Arts 23 (3, 1990): 70-76; 104.

Rosenwald, Jean B. “Kuba King Figures.” African Arts 7 (3, 1974): 26-31; 92.

Quarcoopome, Nii O., ed. Through African eyes: the European in African art, 1500 to present. Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 2010.

Schemmel, Annette. “Antecedents: the emergence of modern art in Cameroon.” Visual arts in Cameroon: a genealogy of non-formal training, 1976-2014, pp. 47-101; 319-331; 379-396. Bamenda, Cameroon: Langaa RPCIG, 2016.

Smith, Alison. “Yoruba artist, Nigeria: figure of Queen Victoria.” In Artist and empire: facing Britain’s imperial past, pp. 188-189, 244. London: Tate Publishing, 2015.

Sprague, Stephen. “Yoruba photography: how the Yoruba see themselves.” African Arts 12 (1, 1978): 52-59; 107.

Steiner, Christopher B. and Jane I. Guyer. To Dance the Spirit: Masks of Liberia. Cambridge, MA: The Peabody Museum, 1986.

Thompson, Robert Farris. “Of genre and the Queen Victoria.” In Black Gods and Kings, Chapter 17. Los Angeles: University of California, Museum and Laboratories of Ethnic Arts and Technology, 1971.

Thompson, Robert Farris. “Esthetics in traditional Africa.” In Carol F. Jopling, ed. Art and aesthetics in primitive societies, pp. 374-381. New York, E.P. Dutton, 1971.

Vansina, Jan. “Ndop: Royal Statues among the Kuba.” In Douglas Fraser and Herbert M. Cole, eds. African Art and Leadership, pp. 41-53. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1972.

Heads from Ile-Ife: Portraits to Symbols

Does naturalism in human representations always indicate the portrait of a particular individual? This is not a frequent question when dealing with older African art, where generic faces are the norm. When we consider

the 15th-century brass, bronze, and copper heads of the Yoruba city of Ile-Ife, however, it is apropos. One crowned head was uncovered in 1910, ostensibly from a sacred grove (Fig. 493). In 1938-39, however, additional larger heads were recovered from one location, the Wunmonije Compound, during an emergency archaeological rescue prompted by the digging of a house foundation (Fig. 494). Altogether there are three smaller, crowned examples (Fig. 495), while 16 are life-sized and uncrowned (one was found in Ado-Ekiti, about 47 miles away). Scholars have suggested the small holes at their hairline indicate a real crown was once attached to these larger heads, however.

These heads are far more realistic than most African artworks from the pre-colonial period; their modeling faithfully recording the hollows and projections of the face in natural proportion. Similar naturalism can be found in the many terracotta heads and figures found throughout the city, some dating to a few centuries earlier. Idealism is likely present–for it is unlikely all the subjects would have been about the same age when they were depicted–yet a high degree of individuality manifests in most heads

(Fig. 496). This does not, however, guarantee that the heads replicate the physiognomy of the specific men they were intended to represent, particularly when the age factor is considered.

Whom do the heads represent? The general scholarly and palace consensus is that they represent historical monarchs whose official title was the Ooni of Ife. The land on which they were found is remembered as once having belonged to the palace grounds, the palace’s structure and boundaries having shifted through centuries that periodically saw it abandoned due to war, then rebuilt. Copper or copper alloys–an expensive metal that was the privilege of monarchs during this period–was used. The smaller heads bear beaded crowns of a type that appears on select male figures in metal and terracotta, as well as on metaphorical animal heads that mark a partially-excavated royal grave. Not all scholars agree; art historian Rowland Abiodun believes that representations of the ruler, considered a semi-divine being, would have been an instance of lèse-majesté before the 20th century.

What purpose did the heads originally serve? This remains open to argument. One theory suggests they were used in funeral rites as an effigy of the deceased, nailed to wooden bodies that were then dressed, with actual crowns temporarily attached to the larger heads. While no such effigies are used today, the Yoruba kingdom of Owo has documented the use of life-size wooden figures for the funerals of prominent persons, though not for their monarch. In the Benin Kingdom of the Edo, which has a historical relationship with Benin, such effigies have been documented for the ruler, his mother, and certain prominent chiefs. However logical this possibility at Ife might seem, contemporaneous full figures all show Ife male dress consisted of wrappers that left the chest bare (except, in some cases, for beaded necklaces); robes in the region seem to represent fashion changes from later centuries. Nails did punch through the necks of the figures–some remained in a few cases–so they do seem to have been attached to something made from wood, whether a body or another type of support. Most tellingly, the style of the heads remains too consistent

to document a period covering sixteen reigns; they seem to have been made in a single generation. Another theory suggests they served as temporary supports for the royal crowns of the Yoruba states founded by Ife. Up until the early 20th century, when an interregnum occurred in these kingdoms, selection and preparation of a new ruler could take up to three years. His ascension to the throne had to be approved by Ife and, in the past, this could have resulted in those state crowns being kept at Ife from the time one ruler’s death occurred and the next monarch was approved. An additional scholarly interpretation is that the heads represent powerful chiefs, lineage heads from two dynasties whom a particular monarch integrated under his rule.

We cannot be sure these heads were ever portraits in the sense of individualized, accurate images representing a particular person, regardless of their naturalism. However, their imagery has come to represent a kind of portrait of Ife (Fig. 497), of Yoruba history, of Nigeria, and of Africa as a whole (Fig. 498), as Ife’s imagery has spread internationally in everything from Romare Bearden works to Brazilian park ornamentation (Fig. 499). They variously represent Ile-Ife as the place the Yoruba style as the place the world began in primordial times, or the birthplace of a complex artistic and religious culture that can match that any existing elsewhere.

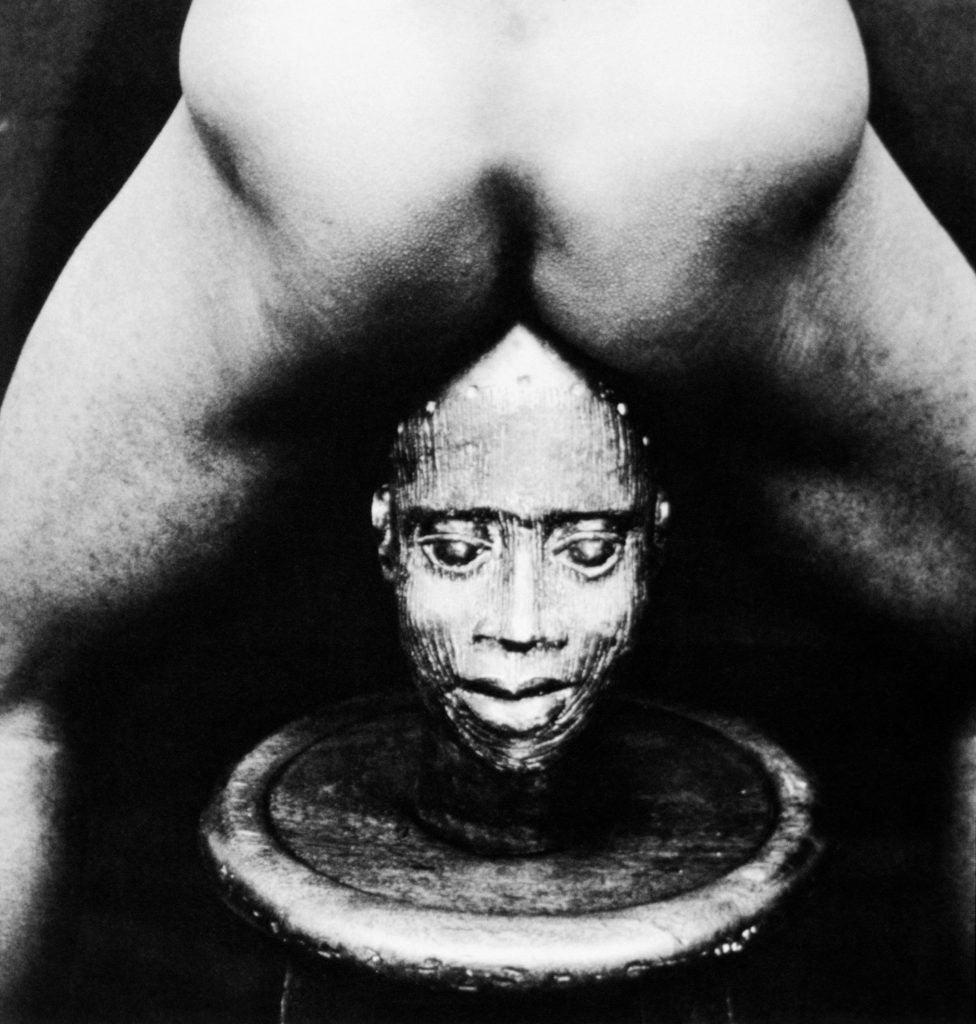

They have not been without their controversies. Rotimi Fani-Kayode, a Yoruba-born photographer whose career blossomed in London, featured an Ife-

style metal head in his image “Bronze Head” (Fig. 500). This work’s subject matter has an autobiographical aspect, for Fani-Kayode’s family, which fled with him to London when he was a child, was from Ile-Ife. His father, Chief Victor Remilekun Fani-Kayode, was a prominent lawyer involved with Nigeria’s independence movement. He was Deputy Premier of Nigeria’s Western Region when a coup ousted him from office, followed by a counter-coup and the beginning of the Nigerian Civil War. In addition to a prominent political career, he was a traditional Ife chief; Rotimi Fani-Kayode stated his family was in charge of Ife’s Ifa shrine, though his familiarity with it was limited, due to his upbringing in Britain. As a gay man, he was rejected by his family; diagnosed with AIDS, he faced other bigotry in London. This work, one of few that explicitly reference Yoruba art, shows a nude male torso, its head, torso, and lower legs cropped, in close conjunction with a reproduction of an Ife head. Various scholars–as well as Fani-Kayode’s partner, artist Alex Hirst–have suggested the figure is either being penetrated by the head or giving birth to it, interpretations that consider complex interweavings of spirituality and gender fluidity. They usually note that the display of bare buttocks is a deliberately rude gesture; might not the figure equally be excreting the head, since its orifices are deliberately shadowed and vague? If so, is Fani-Kayode relegating the restrictions and proscriptions of culture to toxins that need to be expelled? Below the head is a round form that likely is a Cameroon Grassfields stool, everything but its seat shrouded in shadow. Its form and its raised border recall Yoruba Ifa divination trays (see Chapter 3.6), the site of priestly interpretation of one’s problems, one’s past, and the sacrificial acts needed to return life to equilibrium. Whatever its correct interpretation may be, “Bronze Head” is ambiguous in its relationship with the Yoruba past. It does not embrace received culture.

Another replica of an Ife head (Fig. 501) drew international attention as one of the “archaeological artifacts” that English artist Damien Hirst included in his panned 2017 exhibition “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable.” Among the “ancient” objects purportedly recovered from the fictive shipwreck of a first-century vessel filled with treasures, it is an anachronism, as are the coral-incrusted inclusions of the Aztec calendar, Mickey Mouse, and Optimus Prime. The Ife work, however, was singled out by Nigerian artist Victor Ehikhamenor, who was exhibiting at the nearby Venice Biennale. In a series of tweets that went viral in the art world, he suggested future Nigerians would be told the work originated with Hirst, and that it was unattributed cultural appropriation, despite references to Ife in the catalogue and exhibition panels. Perhaps worthy of greater comment is Hirst’s (or his team of creators) laziness in examining actual Ife heads, whose “hair” treatment and profile crania are very different. Nonetheless, Ehikhamenor’s reclamation of a head Hirst labeled as “Golden Heads (Female)” drew attention to the ever-evolving notions of portraiture.

Further Reading

Abiodun, Rowland. “A reconsideration of the function of Àkó, second burial effigy in Òwò.” Africa 46 (1, 1976): 4-20.

Abiodun, Rowland. Yoruba art and language: seeking the African in African art. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Bailey, David. “Photographic animateur: the photographs of Rotimi Fani-Kayode in relation to black photographic practice.” Third Text no. 13 (Winter, 1991): 57-62.

Blier, Suzanne. “Art in Ancient Ife, Birthplace of the Yoruba.” African Arts 45 (4, 2012): 70-85.

Blier, Suzanne. Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba: Ife History, Power, and Identity, c. 1300. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Borgatti, Jean M. and Richard Brilliant. Likeness and beyond: portraits from Africa and the world. New York: Center for African Art, 1990.

Drewal, Henry John and Enid Schildkrout. Dynasty and Divinity: Ife Art in Ancient Nigeria. New York: Museum for African Art, 2009.

Drewal, Margaret Thompson. “Portraiture and the construction of reality in Yorubaland and beyond.” African Arts 23 (3, 1990): 40-49; 101-102.

Dumouchelle, Kevin D. “Beyond the body boundary: queer(y)ing the photographs of Rotimi Fani-Kayode and Samuel Fosso.” In Charlotte Baker, ed. Expressions of the body: representations in African text and image, pp. 63-93. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2009.

LaGamma, Alisa. Heroic Africans: legendary leaders, iconic sculptures. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.

Moffitt, Evan. “Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s Ecstatic Antibodies.” Transition No. 118 (2015): 74-86.

Nelson, Steven. “Transgressive transcendence in the photographs of Rotimi Fani-Kayode.” Art Journal 64 (1, 2005): 4-19.

Poynor, Robin. “Ako figures of Owo and second burials in Southern Nigeria.” African Arts 21 (1, 1987): 62-63; 81-83; 86-87.

Willett, Frank. “On the Funeral Effigies of Owo, Benin and the Interpretation of Life-Size Bronze Heads from Ife, Nigeria.” Man, n.s. 1 (1966): 34-35.

Willett, Frank. Ife in the History of West African Sculpture. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967.

Willett, Frank with Barbara Blackmun. The Art of Ife: A Descriptive Catalogue and Database (electronic CD-ROM). Glasgow: The Hunterian Museum, 2004.

Bringing Photos to Life: J. A. Green as Inspiration in Benin City and Buguma

Many African portraits are less an individualized representation than they are projections of a

particular position or status. In the Benin Kingdom, for example, brass casters produced heads representing kings for royal ancestral altars (Fig. 502). For any given era, these were produced in fairly identical pairs or sets of pairs. When placed on a ruler’s altar, they were intended to portray glorified kingship, rather than represent a particular monarch. The coral netted crown had to be an accurate portrayal (the design varied over time), but during any given time period, the ruler’s facial features were idealized and generic, indistinguishable from those on any other figurative depictions. This had changed by the late 20th century, when photography’s popularity began to affect the casting guild’s art (see Fig. xxx). Photos themselves had been popular for many decades, and homes of both royals and commoners were filled with large framed photographs of family members. Like photos, calendars depicting the Oba (Fig. 503) or members of clubs and other organizations are still a staple of interior decoration.

Since the British invasion of 1897, all Benin monarchs have been photographed. Oba Ovonramwen was the first to undergo this process, and did so through a series of images taken as he was being transported to Calabar, exiled by the British. Although J. A. Green, an Ijo photographer, captured him in multiple poses and outfits, the best-known photo today is the one that depicts him seated on the deck of the S. S. Ivy, a British steam yacht, backed by three soldiers of the British-run Niger Coast Protectorate Force (Fig. 504). While these men were ostensibly the Oba’s guards, they are posed like the courtiers and pages who would have stood in his presence at court. Although his seated frontal position, expensive embroidered robes, and sober demeanor mark him with dignity, his bare head and the absence of all coral beads would have been unthinkable just a year before. The photograph commemorates the solemnity and extreme sorrow of this moment in Benin history, particularly the sight of the chains at his feet.

Despite its commemoration of a low point in Benin history, this photo has provided source material for several bronze sculptures in the form of relief tablets (Fig. 505). The artist who made this example, Uyi Omodamwen, is a member of the Omodamwen family, well-known brassworkers based in Benin City. Although the family constitutes part of the hereditary royal brass casting lineages, its members live outside Igun Street, where guild members traditionally work and stay, and own their own foundry. This work was commissioned by Stockholm’s Etnografiska Museet, but additional examples of this same subject were produced by other family members. They take the form of 16th-century plaques, although they are in much higher relief. The naturalistically treated Oba shows signs of age and specificity, unlike examples from centuries ago. His proportions, however, are compressed, probably due to the visual confusion generated by the photographic combination of his frontal gown and seated pose. Omodamwen’s interpretation included other shifts. He standardized the height of the guards and removed the background, but retained the shackles on the Oba’s ankles.

Those shackles vanish in a public sculpture of Oba Ovonramwen that stands in Benin City’s King’s Square, just outside the palace. This naturalistic work was modelled after

a different Green photo of the Oba bound for exile (Fig. 506). The artist aged the monarch and trimmed his hair. More tellingly, he placed the oba on a throne instead of a deck chair, removed his smile, and added a coral bracelet. Although the artist’s name is unlisted, he seems to have been academically trained, the work’s conservatism suggesting his training took place in Nigeria. This same photograph served as a jumping-off point for artist Osaretin Ighile, who created a life-size reinterpretation of the photo made from found objects. The Oba here is assembled from wood,

metal, and plastic, the open-worked crates reminiscent of the original deck chair’s wickerwork. Detritus forms his wrapper and spills over into the environment—is it a comment on Westernization and the negative effects of consumerism, a process introduced with the colonialism that followed Ovonramwen?

Not all contemporary portraits of this historic monarch are based on Green’s photographs. A brass sculpture by the Omodamwen workshop plucks the Oba from the S. S. Ivy and places him in a canoe, accompanied by one of his wives and her attendant, a chief, four Britons, and two Ijo or Itsekiri paddlers (Fig. 507). Ignoring the British confiscation of the royal corals, the artist depicts the Oba as the central figure, his dignity upheld by his full beaded regalia and his stoic, unmoving frontal position. A more recent public sculpture in King’s Square (Fig. 508) shows the monarch before the British invasion, accompanied by two leopards (one now damaged), along with a chief and a page bearing ceremonial weapons. In a nod to contemporary prudishness, the once-nude page wears a loincloth.

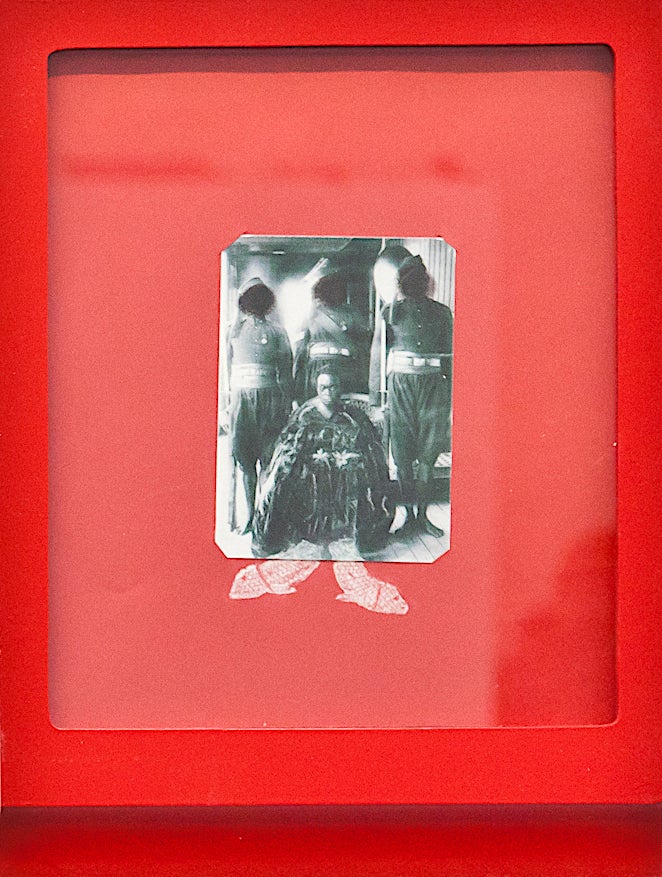

A simmering brew of nostalgia, indignation, and veneration activates the work of another

expatriate Edo artist, Leo Asemota, a photographer, performance and installation artist, and videographer. As part of The Ens Project, a performance/installation/series project, the London-based artist encased a reproduction of Green’s photo in a red shadowbox, forefronting the color associated with power, war, and death, naming it Behold the Great Head (Fig. 509), a reference to the sacred head of the Oba, which is honored in the annual Igue ceremony. In a semi-ritualistic practice, Asemota used two substances–coal and imported “chalk” (white kaolin)–to alter the image. The guards’ faces are erased by the coal, a material the artist associates with Britain’s 19th-century industrialization and subsequent drive for colonization. “Chalk”–a substance used in ceremonies to signify joy, peace, and all things good–is used to add mudfish to the oba’s feet, aligning the photo to some 16th-century plaques and later bronzes (Fig. 510) that return the monarch to his status as a semi-divine being (for more concerning this association, see Chapter 4.6).

Green, who appears to be the first Nigerian professional photographer, has continued to influence artists, not only in Benin City, but in his hometown of Bonny. There his photographs of prominent turn-of-the-century Ijo chiefs have been transformed into life-sized paintings and public sculptures, examples of the impact of portrait photography on contemporary African art. He is not alone; other painted portraits based on photographers’ work–whose impact is increased by colorization and aggrandizement–decorate private and semi-public spheres as well (Fig. 511).

Further reading

Anderson, Martha G. and Lisa L. Aronson, eds. African Photographer J. A. Green: Reimagining the Indigenous and the Colonial. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2017.

Anderson, Martha G. and Lisa L. Aronson. “Jonathan A. Green: An African Photographer Hiding in Plain Sight.” African Arts 44 (3, 2011): 38-49.

Blackmun, Barbara Winston. “Contemporary contradictions: bronzecasting in the Edo kingdom of Benin.” In Gitti Salami, ed. A Companion to Modern African Art, pp. 389-407. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2013.

Blackmun, Barbara Winston. “Obas’ Portraits in Benin.” African Arts 23 (3, 1990): 61-69; 102-104.

Curnow, Kathy. Iyare! Splendor and Tension in Benin’s Palace Theatre. Held at The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology; with entries by Halpern-Rogath Art History Seminar participants, 2008. Cleveland, OH: 2016.

Gore, Charles. “Casting Identities in Contemporary Benin City.” African Arts 30 (3, 1997): 54-61; 93.

Kaplan, Flora S. “Fragile Legacy: Photographs as Documents in Recovering Political and Cultural History at the Royal Court of Benin.” History in Africa 18 (1991): 205-237.

LaGamma, Alisa. Heroic Africans: legendary leaders, iconic sculptures. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.

Nevadomsky, Joseph. “Casting in Contemporary Benin Art.” African Arts 38 (2, 2005): 66-77; 95-96.

Nevadomsky, Joseph. “Contemporary Art and Artists in Benin City.” African Arts 30 (4, 1997): 54-63; 94-95.

Nevadomsky, Joseph. “Iconoclash or Iconoconstrain: Truth and Consequence in Contemporary Benin B®and BrassCastings.” African Arts 45 (3, 2012): 14-27.

Nevadomsky, Joseph. “Photographic Representations of the Oba in the Contemporary Art of the Benin Kingdom.” Critical Interventions 9 (3, 2015): 219-229.

Ogene, John. “The Politics of Patronage and the Igun Artworker in Benin City.” African Arts 45 (1, 2012): 42-49.

Plankensteiner, Barbara, ed. Benin: Kings and Rituals. Ghent: Snoeck, 2007.

Spring, Chris. “Leo Asemota’s: The Ens Project.” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art No. 44 (May, 2019): 78-92.

Staples, Amy J. Fragile legacies: the photographs of Solomon Osagie Alonge. London: Giles, 2017.

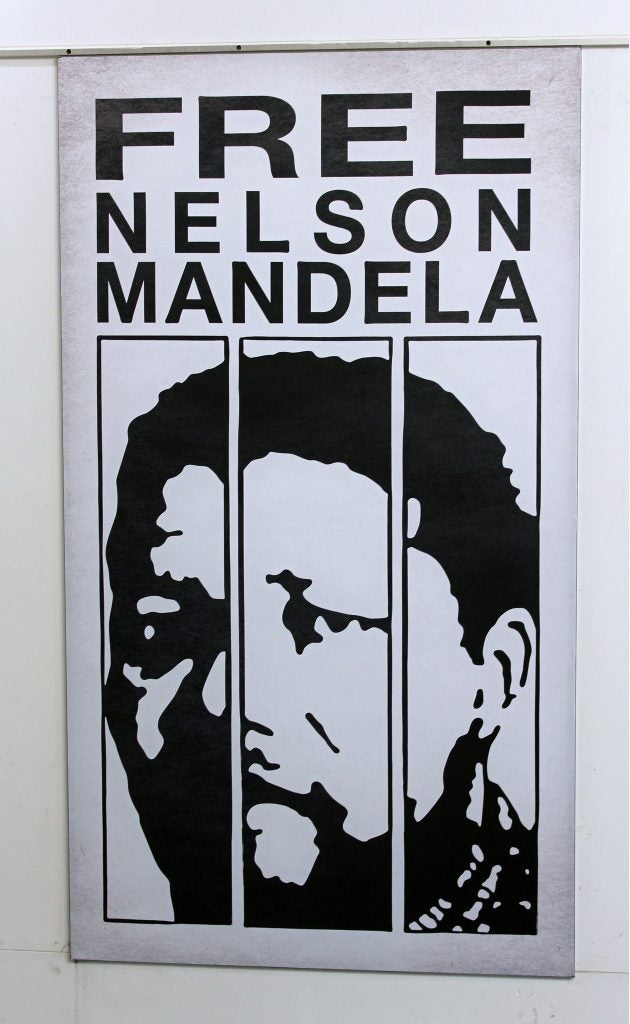

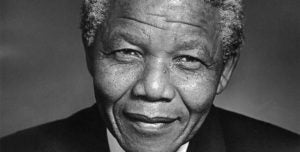

The Most-Recognizable African: Nelson Mandela

The late Nelson Mandela, spearhead to apartheid’s end and a new inclusive South Africa, probably had and has Africa’s most identifiable face. From the t-shirts and posters (Fig. 512) bought by supporters worldwide during his prison years to the work of international photojournalists during his presidential tenure decades later (Fig. 513).

Sculptures and paintings of him abound, in and out of his homeland. Of those in South Africa, both formal and informal examples memorialize him.

While his grave includes no statuary, several naturalistic public sculptures stand in major South African cities. The Johannesburg statue was the first erected, located in Mandela Square, a plaza in the upscale Sandton region, adjacent to an elite shopping complex (Fig. 514). Unveiled in 2004 when the square was renamed after ten years of democracy, it shows Mandela dancing in a casual shirt–an unusual pose for a former head of state.

Eight years later, one of the same artists created a large Mandela sculpture at Naval Hill in Bloemfontein (Fig. 515). Erected on a platform, it stands in a game reserve in the middle of a city, and was commissioned by a black millionaire as part of a plan for future tourist development. This work frames Mandela more politically. Facing the site where his African National Congress party was founded, he looms over the city from its highest point. Dressed in a suit,

his left hand is raised in the anti-apartheid salute of solidarity, pumped to the word “amandla” (“power”), to which crowds responded with “awethu” (“to the people”). Both dress and gesture were recorded by countless cameras upon Mandela’s 1990 release from Victor Verster Prison.

Mandela’s publicly-funded sculpture (Fig. 516) on the grounds of Pretoria’s Union Buildings–the seat of the South African government–was dedicated at the end of his mourning period, which coincided with South Africa’s Day of Reconciliation. The tallest of his naturalistic statues, its smiling mien and open-armed gesture are meant to show his embrace of the entire population. Its prominent position required the displacement of an earlier monument to a prime minister.

The most recent of the realistic Mandela sculptures (Fig. 517) stands on the balcony of Cape Town’s City Hall, on the very spot where he made his historic speech after his prison relief. His clothing and accessories of the day were reproduced, and he holds a page bearing the first paragraph of his talk in both print letters and braille. Jointly funded by the city and the Western Cape government, it was dedicated the year of his centenary.

While all three of these sculptures mark sites of post-apartheid triumph, one of the most poignant Mandela sculptures is erected along the roadside just out of Howick in KwaZulu-Natal province (Fig. 518). Composed of 50 irregular pieces laser cut from steel sheets, the verticals

align and transform into a representation of Mandela’s face when they are approached via a landscaped path. The work, entitled Release, was erected across from the very spot where Mandela was arrested in 1962 after 17 months of evading capture via disguise and relocation. Viewed from some angles, the rods are reminiscent of prison bars; the artist remarked that the “fifty columns represent the fifty years since his capture, but they also suggest the idea of many making the whole; of solidarity.” Interestingly enough, the focused image shows Mandela not as he was at the time of his arrest, but as the Nobel Peace Prize winner and elder statesman of his later years. The face was composited from numerous Internet photos and a film frame of Mandela, fleetingly manifested–much like the fugitive’s brief moment here before disappearing into confinement for 27 years.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tN6XOG7kcWY

Further reading:

Campbell, Kurt. “To Think as a Boxer.” Transition No. 116 (2014): 120-127.

Laing, Aislinn. “Sculptors ordered to pull rabbit out of Mandela’s ear.” The Christian Science Monitor, Jan 22, 2014.

MacDowell, Marsha and Carolyn L. Mazloomi. Quilts: conscience of the human spirit: the life of Nelson Mandela: tributes by quilt artists from South Africa and the United States. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Museum, in association with the Women of Color Quilters Network, 2014.

Marschall, Sabine. “Commodification, tourism and the need for visual markers.” In Landscape of memory: commemorative monuments, memorials and public statuary in post-apartheid South-Africa, pp. 317-346. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

Miller, Kim and Brenda Schmahmann, eds. Public Art in South Africa: Bronze Warriors and Plastic Presidents. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2017.

Nahas, Dominique. “Evocations and Commonalities.” Ceramics: Art & Perception issue 84 (2011): 94-95.

Schmahmann, Brenda. “An arresting portrayal: Marco Cianfanelli’s Release at the Nelson Mandela Capture Site.” African Arts 51 (4, 2018): 56-69.

Shull, Jodie A. “A Passionate Vision in Steel: The Art of Marco Cianfanelli.” Sculpture Review 65 (3, 2016): 24-31.