Chapter 3: Themes in African Art

Chapter 3.2 Coupling Up

The image of the male-female couple is fairly common in African art. Some couple images represent twins rather than mates, but this chapter explores the former. These do not usually depict specific individuals, but represent a basic adult social unit, a foundation of community. In life, courtship or arranged marriage produces couples.

While these events are not depicted in traditional art, there are traditional art forms that support both processes. Among the Akan of Ghana, for

example, until recently an elaborate decorative comb served as a typical courtship gift (Fig. 184). Its imagery might be generic or pointed–sometimes referring to a defeated suitor, for instance, or including visual notes that signified the would-be husband would be a good provider. Even after marriage, a woman might keep her gifts from old admirers, most of which were meant for display rather than practical use, for they tend to be too large for a comfortable fit in the hand. Wives might additionally receive combs from their husbands after marriage to mark special occasions such as the birth of a child.

Young Zulu women, as well as their counterparts in neighboring ethnic groups, create courtship gifts for young men they fancy. With these they indicate their interest without conversation. These beaded rectangles, usually called “love letters” in English are fairly small, although they may be duplicated to form a necklace (Fig. 185). Although the colors and symbols used by the potential girlfriends and brides have meanings, they are generational and also vary from area to area. Young men may have to have their sisters or mothers help them interpret the meaning and can wear as much beadwork as their female admirers can supply until they make an arrangement to marry.

Wedding gifts related to a new household were popular. In the past, one such standard gift for Nupe brides were terracotta pots. Often these, too, were kept unused, but for a different reason. Bowls, cooking pots, and water containers for daily use were one thing, but wedding gifts were kept aside. Not only did their display constitute a formidable statement about bridal popularity, but the unused pottery could be sold in future if immediate cash was needed. One popular wedding gift was the mange, a smallish, narrow-necked pot for water or palm wine (Fig. 186). In the early part of the 20th century, gifts to princesses or other wealthy women might include flat brass ornamentation on the outside. By the 1960s, wedding guests would buy them from a potter, then take them to a male specialist who would paint them (Fig. 187). By the late 20th century, such gifts were considered hopelessly old-fashioned, replaced by imported Chinese enamel lidded bowls and casseroles.

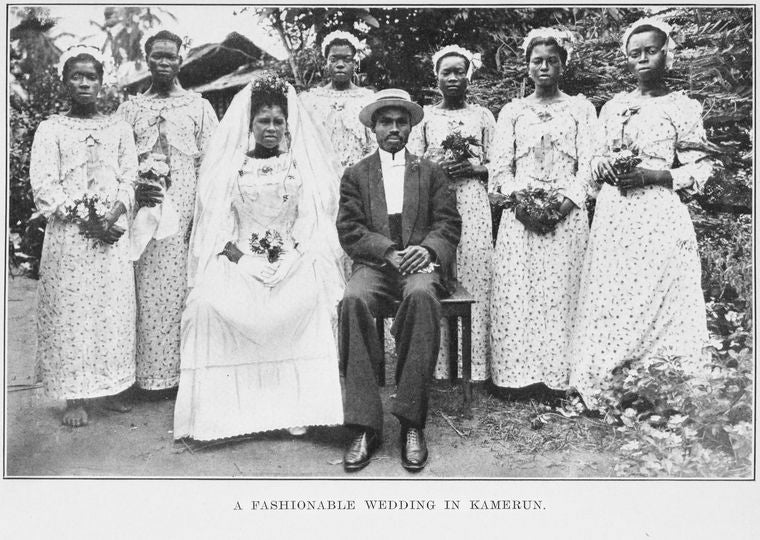

Weddings themselves were and are major family occasions, open to all regardless of invitation. While in the past such celebrations followed traditional law and custom (which usually required “bride price”–a requisite gift that varied from one region to another, but might include livestock, alcoholic drinks, foodstuffs, or cash), contemporary couples often have both a traditional ceremony and a “white wedding”–that is, a wedding with a Western-style wedding gown for the bride, and a suit and white

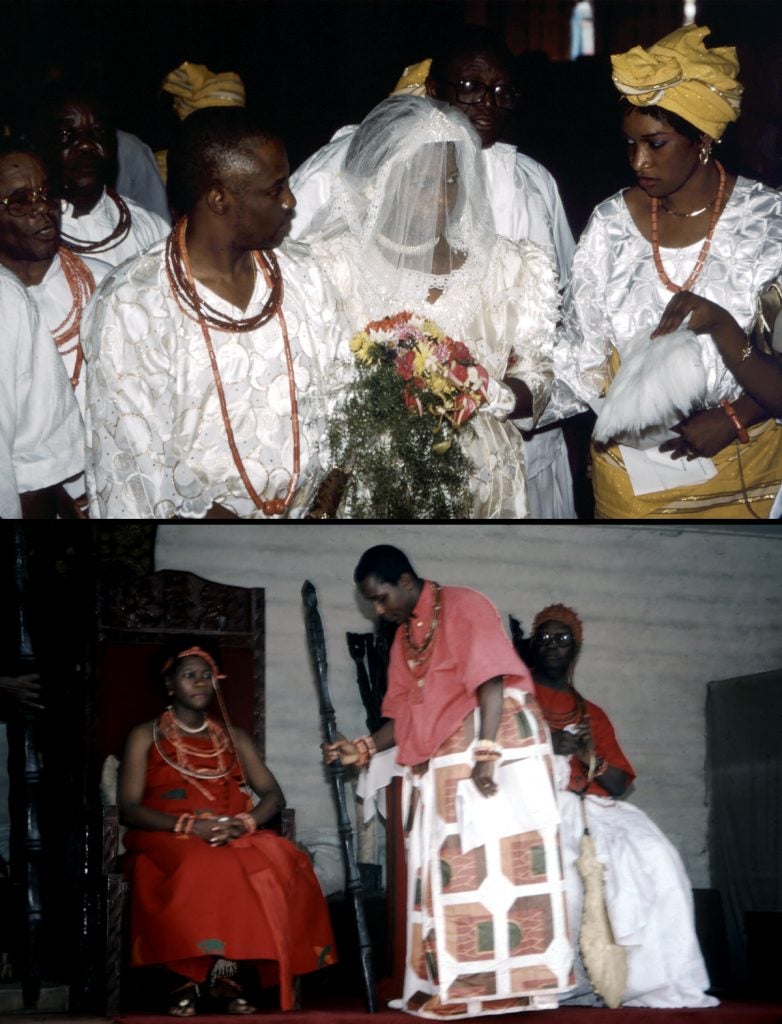

gloves for the groom. Although this adoption of custom began with Christian converts in the late 19th/early 20th century (Fig. 186), it has become very widespread even among non-Christians. Even brides from the most traditional of families may stagger a church ceremony with a traditional one, as occurred in Nigeria’s Benin Kingdom in 1994, when the Oba’s eldest daughter Princess Theresa wed in the Catholic

Holy Cross Cathedral, then shed her gown for traditional attire in a palace celebration (Fig. 189). The Oba of Benin’s two oldest daughters have special weddings, receiving many gifts of beads from their father on the palace dais. Although many Benin brides wear their hair in a beehive-like wedding style imitation of the queens, the Princess could not do so because one of her privileges as the eldest daughter was a coral-beaded headband. This is normally part of chiefly regalia; she, her next youngest sister, and her grandmother (the Oba’s mother) are the only Edo women allowed to wear it.

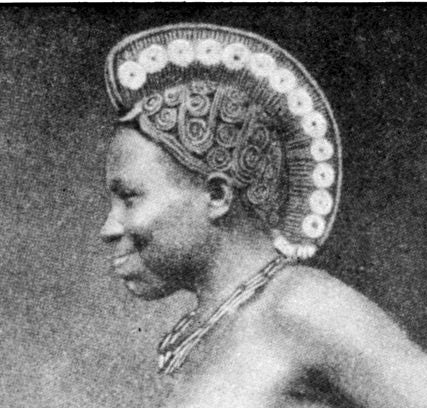

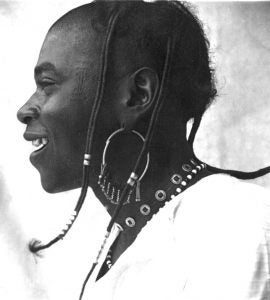

Although high-status versions of traditional wear constitute wedding wear among many African couples, sometimes specific hairstyles or clothing are worn only at the wedding, or during the period immediately following it. Wedding coiffures are usually a female practice, and often used to involve a crest (Fig. 190), since this precluded carrying loads on the head. Avoidance of carrying water or firewood was acceptable and encouraged only for the wedding and labor-free honeymoon periods; sometimes it was reprised during a first pregnancy as well. Certain attire is worn specifically for a wedding in some regions, although this is a fluid tradition that follows its own stylistic changes.

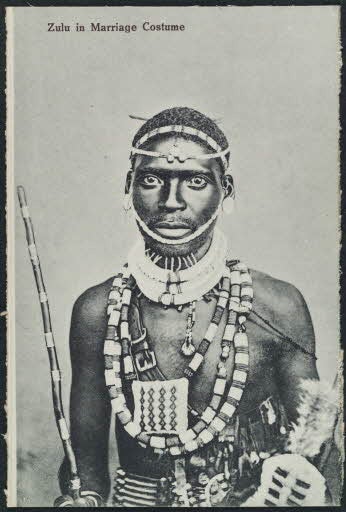

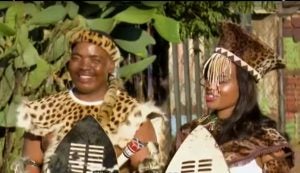

Zulu brides of the late 20th century, for example, transformed cotton blankets with imported glass seed beads, creating splendid (if heavy) multi-colored garments (Fig. 191). In the early 20th century, Zulu grooms wore complex beaded attire created by their brides, dance shields in hand (Fig. 192), and today what appears “traditional” follows neither of these patterns (Fig. 193). Instead, what was once a red-ochred flared hairstyle for married women–not brides–became a wig and then a red hat is transformed for a wedding into a leopard copy of the same form, in line with the groom’s attire, but with an attached beaded veil. Earlier in this 2017 ceremony, the bride wore a white, Western-style gown before changing. Beadwork, however, did not form a major part of either newlywed’s attire.

The sanctioned union created by a wedding is meant to produce children, and occasionally the act of procreation is depicted. Yoruba mirrors with carved frames and covers–a common gift in the early 20th century–occasionally featured the image of a copulating couple (Fig. 194). This was not meant to be a particularly erotic image, but instead a type of visual encouragement to fruitfulness. The motif can show up outside the context of weddings, appearing as one of the carvings on the border of a divination tray or even on a high-status door (Fig. 195), speaking to issues of fertility and sexual health, but also to the matter-of-fact truth that sex is a part of daily life and the continuance of life requires both genders’ cooperation. It can be both licit and illicit, the latter potentially creating problems of some magnitude. Magun, for example, is a well-known type of Yoruba medicine intended to punish unfaithful women and their lovers; secretly applied to a woman by her husband, it makes adulterers unable to disengage after coitus. A diviner or a ritual specialist may have to find a solution for the kinds of frictions and quarrels produced by extramarital sexual activity.

Although erotic subject matter is fairly rare in traditional African art (though not uncommon in 20th-century neotraditional art made for foreigners), recognition of sexuality and its place in marriage certainly exists. Door locks for the Bamana of Mali (Fig. 196) acted as common wedding gifts–the brides’ parents often provided her with a figurative male lock and a door, while a wife often gave her husband a lock in the form of a female figure. no matter the gender of the figure, the lock itself was considered feminine, while the horizontal bar was masculine, and sometimes took a phallic form. The movement of the bar’s slide action during locking and unlocking was conceived of as intercourse, evidence of the created “couple.”

The appearance of a male-female couple can stress the complementarity of the sexes, rather than a husband-wife pairing. While the dual appearances of genders speak to an equivalency of existential value, it does not necessarily translate into societal equality.

Some skin-covered helmet masks or crests from southeastern Nigeria’s Cross Rivers region depict Janus heads or four heads, splitting the genders represented. Although facial features are often styled similarly, the female is usually shown with light skin, while the male has considerably darker skin (see example at Pitt-Rivers Museum, Oxford). Some examples have different hairstyles that further clarify whether they are male and female, while others do not. Sometimes the facial scarification differentiates them. Information regarding their meaning is scarce. Different men’s societies wore them for a variety of functions, including funerals. Are they, in essence, the ideal man–a warrior–and the ideal woman–a nubile graduate of the fattening house? It’s impossible to say with any certainty. Occasionally one will include two females with one man or other idiosyncratic features (Fig. 197), but dual faced normally speak to the male-female pair as the basis of society.

That the concept of the pair shows completeness is visible in many of the continent’s art forms. Architectural features may refer to the couple (Fig. 198), masquerades may contain images of complementary genders (Fig. 199), or figurative sculpture may represent the pair. Marriage is considered one of the benchmarks of adulthood. Even today, it is nearly unthinkable for a person of prominence seeking a government or corporate appointment to be unmarried. This often occurs in art as well, with deities and ancestors frequently shown with spouses. The southern Bamana of the region around Banan and Baninko, for example, have a fertility cult known as Gwan. Its shrine includes a multitude of figures that revolve around a seated female with a child, known as Gwandusu. Her male consort Gwanjaraba, however, must also be present, even though he,

like the baby, is there only to show she is a “completed woman” (Fig. 200). Women seeking a child promise to name the outcome of a successful offering after the figures. In works made for the same shrine by the same artist, he can be smaller than his “wife,” and is sometimes not frontal nor seated, both indications he has less status and dignity.

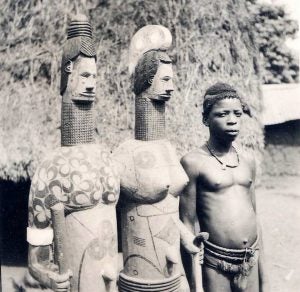

Among the Igbo of southeastern Nigeria, town shrines contained significantly large sculptures of town founders. These community ancestors were remembered more as mythical than as historical figures. They, too, are represented in pairs, accompanied by supporters. Males and females are counterparts of one another, their relative heights reflecting common gender height disparities, rather than a hierarchical relationship (Fig. 201).

Marriage’s creation of a unit is sometimes explicit. A Nigerian sculpture by the Chamba male artist Soompa depicts husband and wife sharing a common lower garment and one pair of legs (Fig. 202). Equivalent in size, the shape of their crested hairstyles is one of their clearest differences. Primary and secondary sexual traits are alluded to, but not emphasized. Instead, their similarities are stressed: elongated cylindrical torsos and necks, as well as identical geometricized facial features.

Similarly, Yoruba edan, metal figures that act as the emblem of the Ogboni (also known as Oshugbo) Society, a group that used to perform judicial and punitive activities in each Yoruba kingdom, equated male and female forms in key ways (Fig. 203). While their primary and secondary sexual characteristics are designated, they are played down–the figures have similar body contours, facial features, and hairstyles. They are literally joined by a metal chain; Ogboni members place the figures on their chest, chain at the back of the neck, when carrying out official duties. Although women cannot take an active role in Ogboni until they are post-menopausal, their importance and powers at that age are seen as equivalent to those of men, and their visual complementarity is sometimes even more extreme–a jawline border often acts as a stylized beard on both figures, a reminder that some post-menopausal women have (albeit limited) facial hair. Scholars may dispute the identity of the figures–Ogboni founders? representatives of the androgynous duality of the deified female Earth?–but suggest that efficaciousness of any significance necessitates the complementary and interdependent principles represented by a male-female pairing. In a sense, the edan Ogboni is a symbolic equivalent of the Taoist taijitu emblem representing the principles of yin and yang.

The visual expression of male-female interdependence transcends any particular couple to become a philosophical construct of gender complementarity. It is expressed in many representations of the couple as a kind of archetype, rather than merely individuals who physically interact. Symbolic unity can be achieved by sharing the same seat, a practice that does not occur in everyday life. In an Asante sculpture (Fig. 204), two figures share a stool–a physical impossibility given the size of these seats. Unfortunately, the object was collected without information. Is this a representation of a married couple, demonstrating their unity? While that might be a logical assumption in some parts of the continent, it is unlikely for the Asante. Most stools are extremely personal, and no one except the owner would ever use a given example. There are, however, state stools that act as thrones, and the Asante and other Akan peoples speak of the enstooling of a ruler or of inheriting the stool. To show a couple sharing a stool may indicate that we are seeing a ruler and a Queen Mother, either the ruler’s actual mother or a designated female relative who acts as a stand-in if she is deceased. Queen Mothers are influential, not only dispensing advice but instrumental in the selection of a new ruler. Perhaps this couple–the female shown slightly taller than the male–represents mother and son, but it is impossible to verify without further information.

A Dogon male artist from Mali produced one of the best-known African representations of the couple (Fig. 205a,b). Like the Asante couple in Fig. 204, the male and female figures share a stool. Their hairstyles differentiate them, but otherwise their genders are played down for a more androgynous effect. While the woman has breasts, they are not overlarge, and the male’s chest protrudes as a solid form in a complementary fashion. Some facial features–arrow-like nose, eyes with metal inserts–are identical. While the male’s mouth is larger, the female’s has a similar amorphous shape. The verticality of her labret is a counterpart to his beard. While their genitalia varies, and the male’s gesture draws attention to the concept of procreation, their body silhouettes replicate one another–his shoulders are no wider, her figure does not nip in at the waist nor flare

out at the hips. A symphony of repeated cylinders, they neither mirror actual human forms nor are distinguished from one another. In this, they are similar to the Igbo, Chamba, Yoruba, and Asante pairs already examined. The essence of their message remains complementarity, which is borne out by the vocational symbols on their backs: man as provider, indicated by his quiver, woman as nurturer, symbolized by her child.

The link between these figures is made manifest not only by the stool, but by physical touch–the man’s arm rests across the woman’s shoulders, creating a strong horizontal that echoes those of the stool’s base and seat. Traditional African art rarely portrays eye contact or touch, even in depictions of husband and wife. Is this an ordinary husband and wife? We do not know the function of this object or similar Dogon pairs–for this is not a unique object (See Fig. 206)–because they have not been made or used since the early 20th century. While these examples are similar in many respects, there are other analogous pieces whose facial style is vastly different or that lack the caryatid stool.

Were they personal objects owned by individuals, sculptures belonging to the extended family’s shrine, works on the shrine of the hogon, the village priestly leader? Were they displayed at the funerals of prominent men or used in a completely different context? Both pairs illustrated here show the couple seated on a stool with figurative caryatids; this refers to the kind of stool only the hogon owned (Fig. 207). Scholars have often referred to the supporting figures as nommo, primordial ancestral beings who brought agriculture to the Dogon and create rainfall. According to a group of French scholars headed by the late Marcel Griaule, such stools are models of the cosmos, the seat representing the sky connected by a central tree (a post) to the base, the earth. That the couple sits upon such a stool both conveys leadership associations and suggests an identity out of the ordinary–that of the primordial couple, or first human beings. Is that indeed their identity? Religious discontinuities since the early 20th century prevent any certainty concerning the exact meaning and function of these and similar works. Despite our ignorance regarding this key information, the object’s imagery does convey key cultural ideas regarding male and female interdependence, equivalent value, and

divergent social roles.

Although polygamy is not uncommon in Africa–particularly among the wealthy–it has rarely been the subject of traditional art. The couple alone can represent the complementarity of the sexes and convey information about roles. A few traditional pieces do address multiple wives, however, as do some contemporary works.

A small group of late 19th-century Igbo terracotta sculptures places the male head of household at the center of a dense figurative cluster. With their masterful handling of surface patterning, these sculptures attest to the skills of a single village, for they were all collected from Osisa, an Ndokwa Igbo community on the west bank of the Niger River. The family head is (Fig. 208) usually flanked by two wives with a carved ivory tusk in his left hand–a reference to his high status as a titleholder–while a member of his entourage beats out a rhythm on an iron gong. He and his wives hold fans; his imported hat also attests to his high position, as do their elaborate hairstyles. Fecundity is underscored; one wife holds a baby to her breast, while some other examples (Fig. 209) show one wife pregnant, the other with a child. The chickens in these works await their fate as sacrificial offerings; the objects were apparently altars dedicated to Ifejioku, the god of yams, the Igbo farming and culinary specialty. Today shrines to Ifejioku (“Ifijioku” in other Igbo areas; a male deity in the Ndokwa region) are small marked-off areas of the ground that support a wooden stake. Human and plant fertility are inextricably linked, and wives, children, and retainers are testaments to the success of a wealthy farmer.

Some artworks refer to polygamy without the physical presence of the husband (Fig. 210). While the image of two women pounding food in a mortar together might depict any two women–mother and daughter, sisters, mother and daughter-in-law–it is usually interpreted as an image of co-wives. A metaphor for smooth cooperation, since a rhythmic alternation of strokes is necessary, such images can speak to the ideal polygamous family, where all members coexist in harmony. When sculptures are part of a performance, however, as these puppets are, the pestles sometimes become weapons as the women’s rivalry is made manifest. Jealousy among co-wives is common.

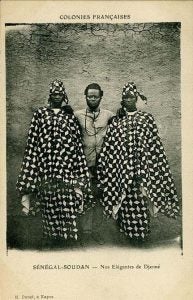

Among West African Muslim families, men are supposed to avert it as much as possible by purchasing their wives the same items, and when these are worn at the same time, the ideal is achieved, if only for a moment (Fig. 211).

In actual domestic settings, household arrangements for husband and wife tend to follow patterns of gender separation. Traditional housing–except for very poor urban dwellers–usually ensures husband and wife or wives have their own houses within a compound (Fig. 212). While a double neckrest (Fig. 213) attests to the incomplete nature of domestic separation, double beds in most women’s houses or rooms are usually meant to be shared with their children, not their spouses. Urban homes in traditional forms, such as those in Djenne, Mali or in Nigeria’s Hausa cities, usually site the women’s quarters in the compound interior, so that the husband’s room has a street or entry view, and passage into the interior of the household is restricted to family or close friends. This has even carried over to modern styles of houses and apartments–as long as it is affordable, a husband and wife/wives will each have their own room. Wealthy men may provide separate dwellings–sometimes in different towns–for their wives.

Observations of modernity and its impact on couplehood have impacted some artists. Each region has its own standards for one gender’s behavior toward the other, but a degree of separation is common, as is avoidance of affection in public. Early in the 20th-century sculptors began to record the odd couple behavior of foreign colonials, who ate together at a table (Fig. 214), walked with their arms around each other, or even kissed in public, all evidence of unmannerly behavior. Later responses to modern couplehood–African and foreign alike–attracted artists’ eyes (Fig. 215) as the impact of European influence–through direct observation, film and television productions–appeared.

Further Reading

Arnoldi, Mary Jo. Playing with Time: Art and Performance in Central Mali. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1995.

Berns, Marla C. “Art, history, and gender: women and clay in West Africa.” The African Archaeological Review 11 (1993): 129-148.

Cole, Herbert M. Icons: Ideals and Power in the Art of Africa. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989.

Cole, Herbert M. and Chike C. Aniakor. Igbo arts: community and cosmos. Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History, UCLA, 1984.

Curnow, Kathy. At Home in Africa: Design, Beauty and Pleasing Irregularity in Domestic Settings. Cleveland, OH: The Galleries at Cleveland State University, 2014.

Ezra, Kate. Art of the Dogon: Selections from the Lester Wunderman Collection. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988.

Ezra, Kate. A Human Ideal in African Art: Bamana Figurative Sculpture. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1986.

LaGamma, Alisa. Echoing Images: Couples in African Sculpture. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.

Lawal, Babatunde. “À yà gbó, à yà tó : new perspectives on Edan Ògbóni.” African Arts 28 (1, 1995): 36-49.

Nzei, Alexander Alezei. “Women and Power: A Case Study of the Ndokwa-Igbo Speaking People West of Niger River, Nigeria.” M.Sc. Thesis, University of Nigeria, 1992.

Roy, Christopher. “Marriage and Eligibility.” Art and Life in Africa website, University of Iowa.

Rites of Courtship, Ceremonial Displays of Wedded Bliss: The Nomadic Fulani of Northern Nigeria, Niger, and Neighboring Regions

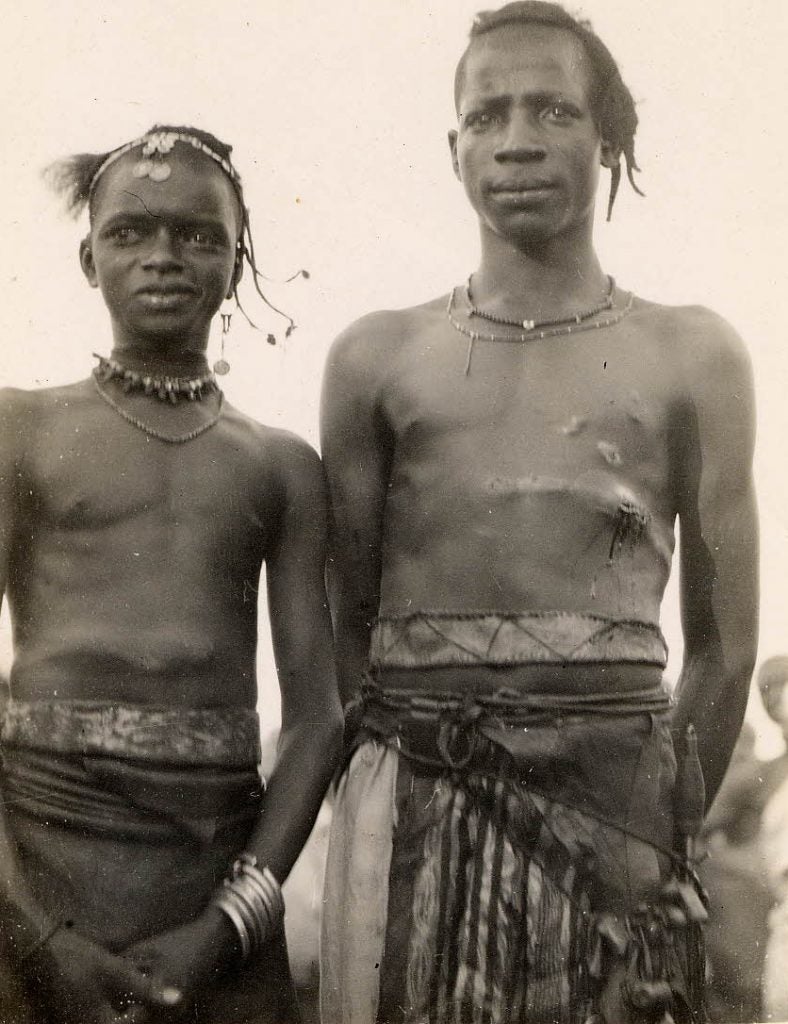

While the Fulani people are spread out among many West African countries and are comprised of both settled and nomadic populations, two contiguous sub-groups of the latter engage in complex but contrasting courtship rituals. The cattle-herding Fulani who live in Nigeria, Benin Republic, and Cameroon, as well as those who live just north in Niger and Chad share a nomadic lifestyle and an interest in personal adornment through hairstyles, jewelry, makeup, and dress, but are segregated by oral history pertaining to clan origins, and by self-perceived differences.

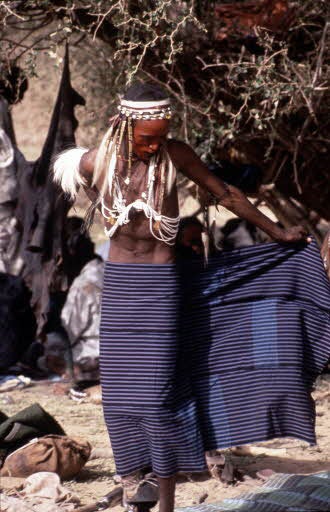

Some aspects of their lifestyle are visually distinguishable, and are particularly apparent during the courtship rituals when the personal beauty of both sexes is the subject of intense effort. As people who are often on the move when new grazing lands are required, their personal possessions tend to be lightweight–the matrimonial bed, mats, calabashes, and personal goods. Their creative efforts therefore become self-directed; individuals themselves periodically become works of art, subject to critique.

Nomadic Fulani in Nigeria, Benin Republic, Cameroon

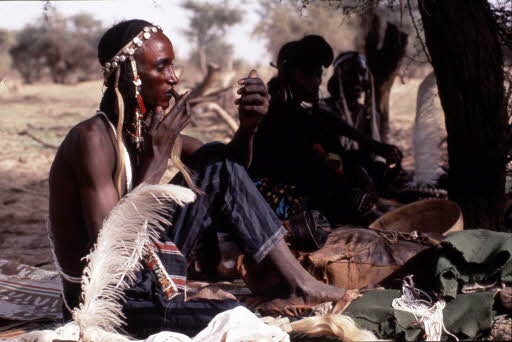

Among those nomadic Fulani who tend to move across a belt that includes northern and central Nigeria,

as well as parts of Benin Republic and Cameroon, male fashions for those who are of courting age have varied considerably over time. Their everyday clothes are usually woven and tailored by the Hausa or are imported. They often wear the straw hats of older men–domed, with a curly or straight brim (meant to accommodate a cylindrical cap and/or turban underneath) or conical (though most conical examples are wide-brimmed) (Fig. 216).

These Fulani youth are subject to changing concepts of the fashionable. Male accessories have included large single earrings (Fig. 217) that had some longevity (Fig. 218), but have long since been out of style, as well as changing jewelry at the neck, arms, and wrists made from beads, leather with brass accents, or imaginative repurposing of imports such as buttons or safety pins. Some males bear facial tattooing (Fig. 216 right), but it is a cosmetic elective rather than an ethnic marker, and is now predominantly a female practice in most regions. On market days, when the often isolated youths visit towns in the hope of encountering Fulani girls, their dressing tends to be more elaborate than when they spend long periods with the cattle, sleeping in the rough.

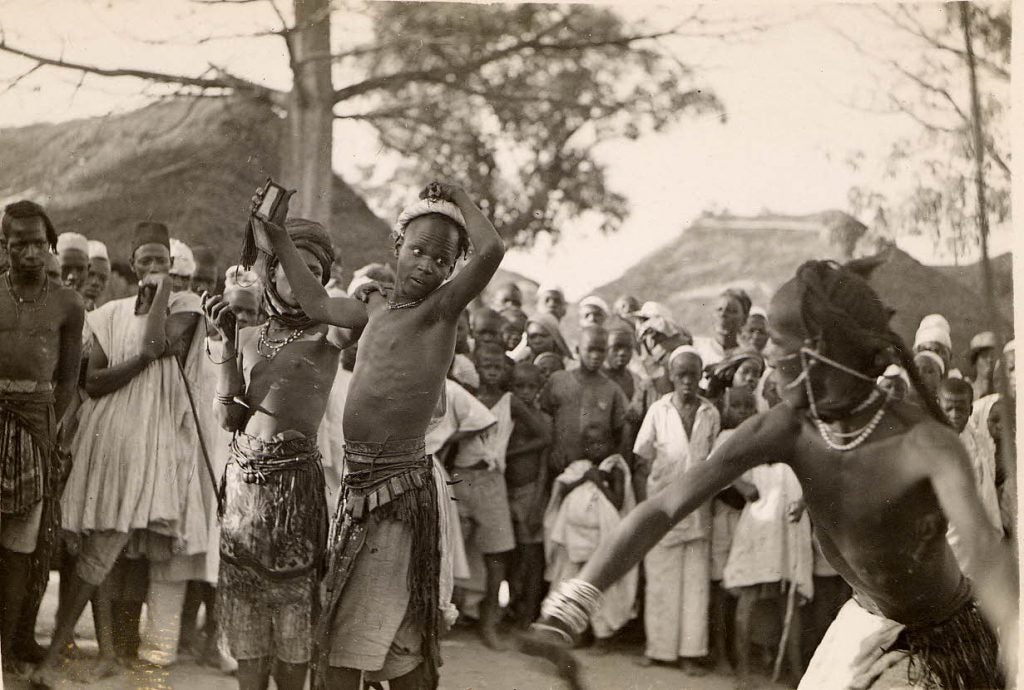

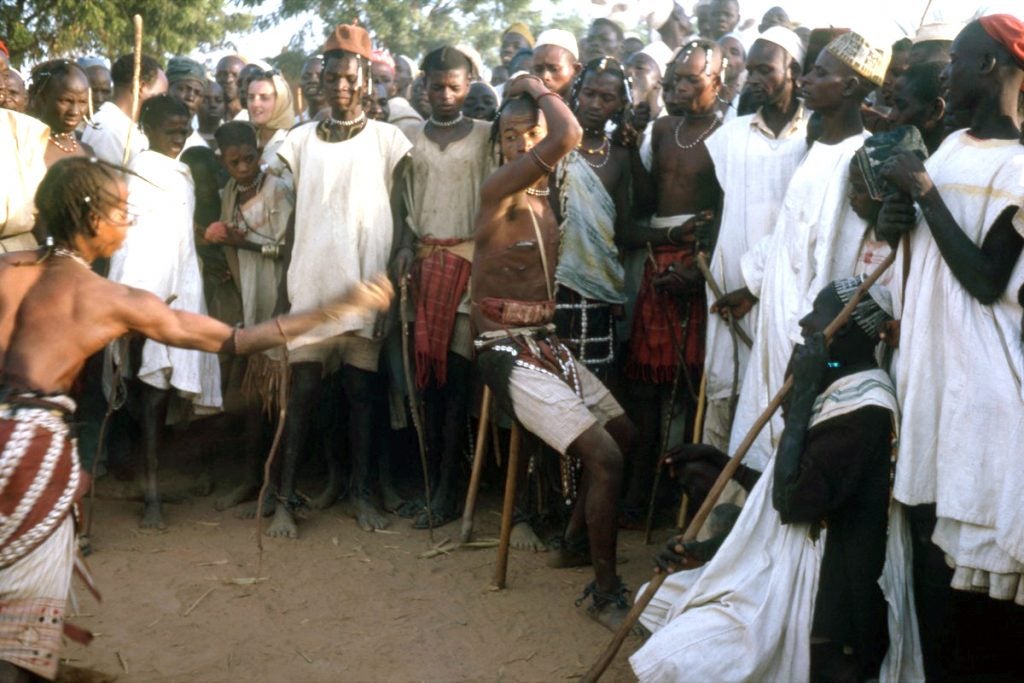

Dressing is at its peak, however, at celebratory times. The biggest occasion for more formal dress is the annual celebration known variously as Sharo, Soro, Goja, or Shadi. Unmarried youths called suka, usually in their mid to

late teens (although this stage can extend until the mid-twenties), meet in paired ritual combat with their counterparts from another community (Fig. 219). Insults are traded by the participants, as well as by female spectators towards rival groups. One youth stands and is whipped by his opponents, often after some feints designed to provoke a reaction. Then, after a recovery period, the initial subject returns the favor. The whips are not leather, but supple tree branches, often with sharpened off-shoots meant to inflict greater damage, the whole prepared with medicine.

The most admired Sharo participants are those who not only show no pain–that is a given; revealing pain will alienate young women seeking husbands–but whose bodies even withstand flinching. The stars of the performance are those who admire themselves in a mirror while receiving blows (Fig. 220), especially if the mirror is held by one of their female admirers. Welts and cuts are

badges of honor (Fig. 221). Willingness to participate, ability to endure with grace even when taunted by girls of the opposing community, and the appearance of diffidence at both the infliction and reception of pain is a key element of Fulani pulaaku, or “Fulaniness.” Endurance is a necessity for the hard life of a nomad, and Sharo underlines the way men face the blows of life.

Sharo dressing has changed considerably in the past century. The 1940s saw suka wearing leather aprons over knee-length shorts, their braids clamped with metal; this remained standard until the 1960s, when they began slipping an abundance of white beads onto their multiple braids (Fig. 222). In the 1990s, copper wire acted like a second coiffure, haloing their heads. More recently headbands or imported hats of various types are a key feature, along with Western shoes and other attire (Fig. 223).

Gaining the favor of girls is intrinsic to Fulani play, even long before the suka stage is reached (Fig. 224). At this stage of life, braids–alien to most of the Fulani’s male African neighbors–are a must. Young women taunted a nomadic youth who had settled in town by saying, “Are you not ashamed to walk around with this head of a farmer?” The youth–Ndudi Umaru, a Jafun Fulani from Cameroon who narrated his autobiography–spoke of suka preparations for the festival:

“A young suka is completely preoccupied with his braids and with girls. He’s never separated from his mirror and his bottles of perfume. He puts salves on his face. He drinks sour milk to which he has added certain powders which are supposed to make him attractive. From his magic belt, he hangs many flasks full of liquid ointments. And he certainly does not forget to obtain ‘the medicine of courage’ from his elders” (Bocquené, [1986] 2002, 120).

Rewards for successful participants include the admiration of peers, elders, and younger boys. The most sought-after result is female willingness to pledge love–innocent for young girls (though perhaps leading to marriage), conclusive for married women.

This endurance contest has been banned off and on in Nigeria, but it is unevenly enforced (Fig. 225). Occasionally rivalries flare up and floggers strike the head instead of the chest, resulting in death and front-page news. Stylized versions without actual blows are a part of some Nigerian state and national cultural festivals. In some parts of Niger, government intervention resulted not in a total ban of Sharo, but an adaption that introduced protective head and chest gear (Fig. 226). This is a considerable departure from remembered practices, but has introduced novel costume elements that may have their own appeal.

Nomadic Fulani in Niger and Chad

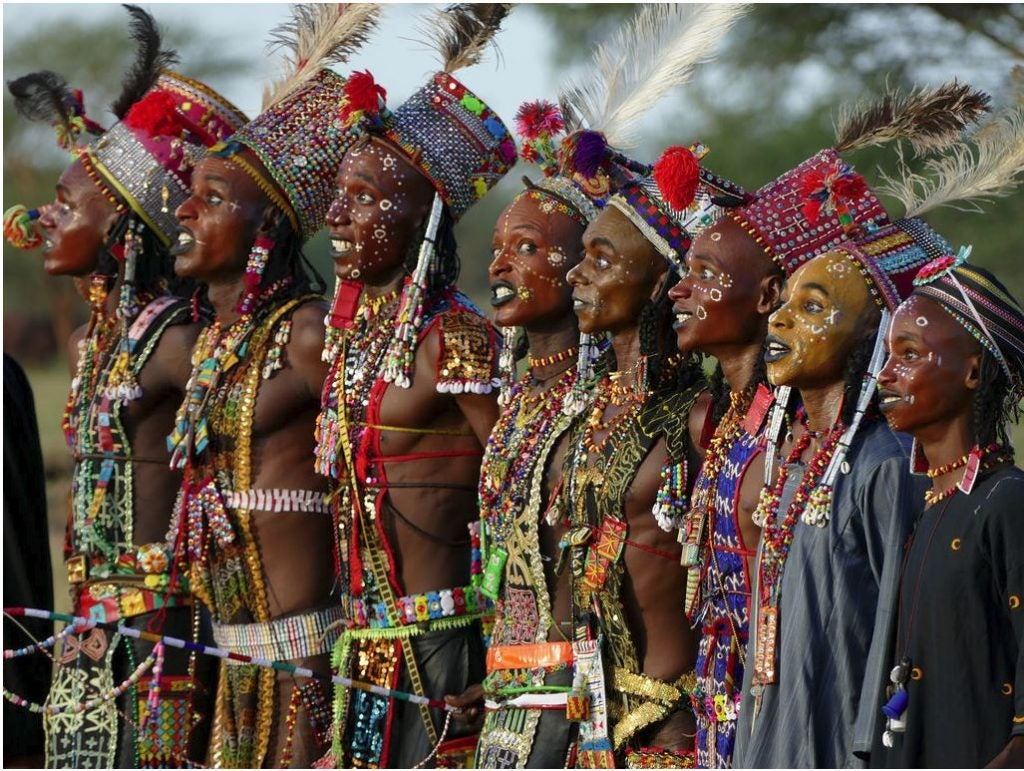

The nomadic Wodaabe Fulani live primarily in Niger, and also have a courtship ordeal of sorts. Known as Gerewol, it involves no physical blows, but puts male pride at stake. Endurance also plays a part in this festival, but in a different manner. Rather than the receipt and administration of physical blows, participants endure exposure to direct sun for most daylight hours during a week of continuous, repetitive dancing. Gerewol takes place far from towns at the end of the rainy season and involves large meetings of two clans. Like Sharo, Gerewol provides opportunities for courtship and marriage, as well as divorce and remarriage. Like all Fulani, the Wodaabe favor first cousin arranged marriages for their initial pairing, but subsequent spouses can be love matches. Polygamy is common and divorce carries no stigma for either spouse. During Gerewol, women may choose to dally with a handsome participant or elope with him.

Fulani appreciation for good looks is socialized at an early age, and small boys are encouraged to admire themselves in the mirror. Gerewol showcases the good looks and charms of young men, but takes these traits much further than those Fulani who practice Sharo. Most nomadic Fulani males and females use tozali eyeliner (ground from antimony, or, more dangerously, galena) on a daily basis–it not only darkens the eyes strikingly, it is said to cut glare and clear the eyes. At Gerewol, however, male participants use additional cosmetics to create an ideal appearance, and also pay careful attention to their clothing and accessories (Fig. 227). Despite rivalry, they assist each other in dressing and making aesthetic decisions. Adult mirrors are constantly at hand and checked regularly (Fig. 228).

Once Gerewol commences, young men begin a series of daily preliminary dances called yaake. Their preparations involve hair neatly braided by female relatives, the polishing of any brass ornaments, a careful choice of attire and accessories, and the application of facial makeup (Fig. 229). The Wodaabe favor a bright complexion, a long narrow face, a long nose, and bright whites of teeth and eyes.

To enhance their natural features and approach the ideal, men create a foundation from clays imported from Nigeria and one region of Niger. Not

only do these yellows (makkara) and reds (kooya) allow them to paint an elongated face within a face–narrow and light–the clays themselves are believed to have inherent medicinal qualities that charm the opposite sex. After applying the base coat, a narrow white or yellow (or white on yellow) stripe is often added from the hairline down the nose, resuming again on the chin. This creates an optical illusion that further lengthens the face, sometimes enhanced by the plucking or shaving of the hairline, as well as the verticality of an ostrich feather stuck in the turban (Fig. 230). Small flowers or dots can be added to the cheeks as an additional embellishment. The eyes are then lined with a dark color, which is also applied to the brows and lips. This substance, which enhances contrast with white teeth and eyes, is also considered to be a medicine. Made from burnt cattle egret bones mixed with butter, this mystical preparation is meant to increase allure. Some Wodaabe use black pigments made from the inside of burnt batteries, and those in Chad have introduced a bright blue as a lipstick color.

Instead of their relatively plain tunics and short pants–or Western attire–young Wodaabe men drastically change their attire for Gerewol. During the yaake dances they wear long open-sided tunics over pants, often with a leather apron visible at the side. In Niger, this attire consists of dark cloths woven by the Hausa and sometimes embroidered with colorful lines, while in Chad tunics are now frequently brighter, embellished with long sequinned or mirrored flaps, the pants with extensively embroidered panels added to the bottom. Chadian Wodaable fashion in recent years has also favored tall multi-colored caps with an abundance of sparkling elements, decorative braid, and yarn pom-poms (Fig. 231). In all regions, amulets are worn around the neck (Fig. 232) or attached to headgear, since rivals from within and without the lineage may try to sabotage a dancer. Medicines directed toward particular dancers are openly buried under the dancing ground in advance; a Wodaabe participant told Ndudi Umaru about other subterfuges, including iron suspended from a cord at one’s back, which would flare out during a twirling step to hit a rival in the genitals, or ostrich plumes dipped in dry hot pepper that could be shaken before a rival, falling into his eyes.

Yaake is danced in a line. While it may not seem strenuous, as it involves stepping in place, spinning,

rising on the toes, and assuming a shivering shoulder movement, it involves constant motion and song. Stylized grimaces show off the whites of the teeth, while eye widening and rolling likewise highlight the brightness and size of the eyes. Participants may break away from the line occasionally for a drink or to arrange a liaison, but they quickly return. They are critiqued for days and often subjected to the insults of old women from the opposing lineage, which they pretend not to hear.

Most Gerewol participants retire from the dance in their late 20s, although some may continue into their 30s. They then assume the role of a sponsor, coaching, grooming, and supervising their favorite, exhorting him to excellence (Fig. 233). The

excitement of the ceremony is so extreme that small boys incorporate it in their daily play, rising on their toes and practicing the facial gestures to the encouragement of the elders.

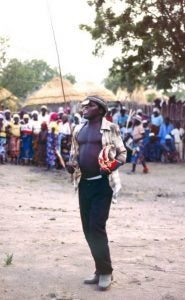

After days of dancing for hours in the heat, some men excuse themselves from the final performance, since only one man will be acclaimed the most perfect specimen, and the potential humiliation may be too much for some to bear. Older men consider body proportions, beauty, charm, and dancing skill, their selection made somewhat easier since much of the individuality of attire is stripped away. All dancers are now bare-chested except for beads, their turbans bearing identical animal tails or feathers, their

lower body swathed in a woman’s wrapper that restricts movement (Fig. 234), each wearing an identical apron topped by beaded strands (Fig. 235). When a consensus is made as to the winner, the elders send a young maiden with attendants forward to announce the winner. She walks in a stylized manner, her right arm languidly rising and falling (Fig. 236), her eyes avoiding the dancers’ eagerness. She approaches, gestures toward the winner, and goes on her way. The selected youth is celebrated, his reputation enhanced.

During the performance, many young and married women alike watch, assessing the performers and deciding if they will marry for the first time or leave their husbands. They too are dressed in their finest (Fig. 237), made from cloths woven by neighboring ethnic groups or imported textiles purchased in the market.

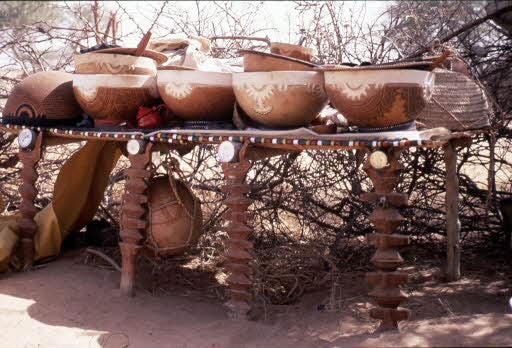

Married women have an aesthetic competition of their own, although it does not involve personal appearance. Instead, it is a curated display of their most precious possessions, calabashes arranged atop their Tuareg-constructed beds. These are not the calabashes women regularly use to transport milk, butter, fried cottage cheese and other specialties to regional markets, nor are they the ones used domestically to store or prepare foods. They are a combination of purchased examples and heirlooms, along with symbolic wedding gifts from mother and mother-in-law.

While some Wodaabe women decorate their own calabashes–often with delicate linear patterns that resemble their facial tattoos–they also buy calabashes from the Hausa and other peoples whose markets they visit (Fig. 238). These lightweight gourd containers are carefully wrapped in fiber pads to prevent damage when the women pack up their household for donkey transport to a new camp.

Wodaabe women are not truly considered married until they bear a child. As soon as they are pregnant, they leave their husbands to return to their mother’s house, where they deliver and remain until the child is weaned. They are not allowed to see their husband until the time of their return to set up a household, and that is when they receive a decorated calabash bundle (elletel) from their mothers, and an even more grandiose one (kaakol) from their mothers-in-law. Amulets are concealed within, and the kaakol is hung over the wife’s bed; men are forbidden to touch elletel or kaakol. These calabash bundles mark a successful accession into approved adulthood, while the individual bowls speak to an individual’s popularity (many were gifts) and taste.

Both bundled and gifted calabashes are displayed at Gerewol for the eyes of other women (Figs. 239, 240, 241), admiration directed not only to the number and exquisiteness of the objects themselves, but to the care in arranging them, often with cloth, dippers, spoons, and basketry covers. No winner is declared, nor does the opposite sex take an interest. They are for the eyes of their peers, a quieter statement of pride in appearance.

Further Reading

Bocquené, Henri. Memoirs of a Mbororo: The Life of Ndudu Umaru: Fulani Nomad of Cameroon [1986]. New York: Berghahn Books, 2002.

Boesen, Elisabeth. “Gleaming like the Sun: Aesthetic Values in Wodaabe Material Culture.” Africa 78 (4, 2008): 582-602.

Bovin, Mette. Nomads who Cultivate Beauty: Wodaabe Dances and Visual Arts in Niger. Uppsala, Sweden: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2001.

Kratz, Corinne Ann. “The case of the recurring Wodaabe: visual obsessions in globalizing markets.” African Arts 51 (1, 2018): 24-45.

Lott, Dale F. and Benjamin L. Hart. “Aggressive Domination of Cattle by Fulani Herdsmen and its Relation to Aggression in Fulani Culture and Personality.” Ethos 5 (2, 1977): 174-186.

National Geographic. “Boy to Man.” 2007.

Pulaku Project, 2010-2011.

Reed, L. N. “Notes on Some Fulani Tribes and Customs.” Africa 5 (4, 1932): 422-454.

Baule Spirit Spouses of Côte d’Ivoire

While the male-female relationship as represented in art and life usually refers to a human pairing, this is not always the case. the Baule people of Côte d’Ivoire believe that before anyone is born into this world, they experienced life in the spirit world. There they had a family–spouse and children–but, once born into the physical realm, they forget about this prior existence. Male or female, they grow up and marry. Some have contented adult lives, but others may show a tendency to have fertility problems or be otherwise troubled, often by a contentious human spouse. After a consultation, a diviner may inform the client that his or her problem is the result of their jealous, neglected spirit spouse. The usual solution is to have this spouse made manifest through a carving, keeping it privately in one’s bedroom and offering sacrifices such as coins, perfume, eggs, or chalk to mollify it. Dreams–those of the human spouse, the diviner, or the carver–allow the spirit spouse to dictate his or her appearance through details of scarification, hairstyle, or stance. One night a week is dedicated to the spirit spouse, with the expectation that erotic dreams will result.

A man’s spirit spouse figure (blolo bla) or a woman’s (blolo bian) can serve as a source of comfort in the setting of a problematic human marriage, and as such have tended to depict the otherworld husband or wife as an idealized spouse. Within the 20th century, Baule ideas of what constituted an ideal husband or wife changed considerably, as the impact of French colonization and post-colonial shifts in the country impacted daily life.

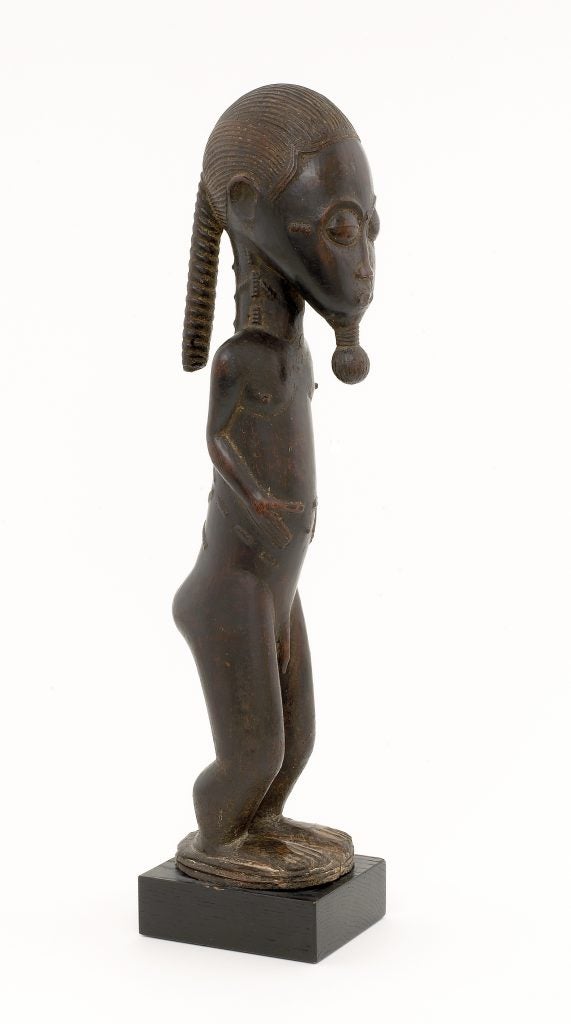

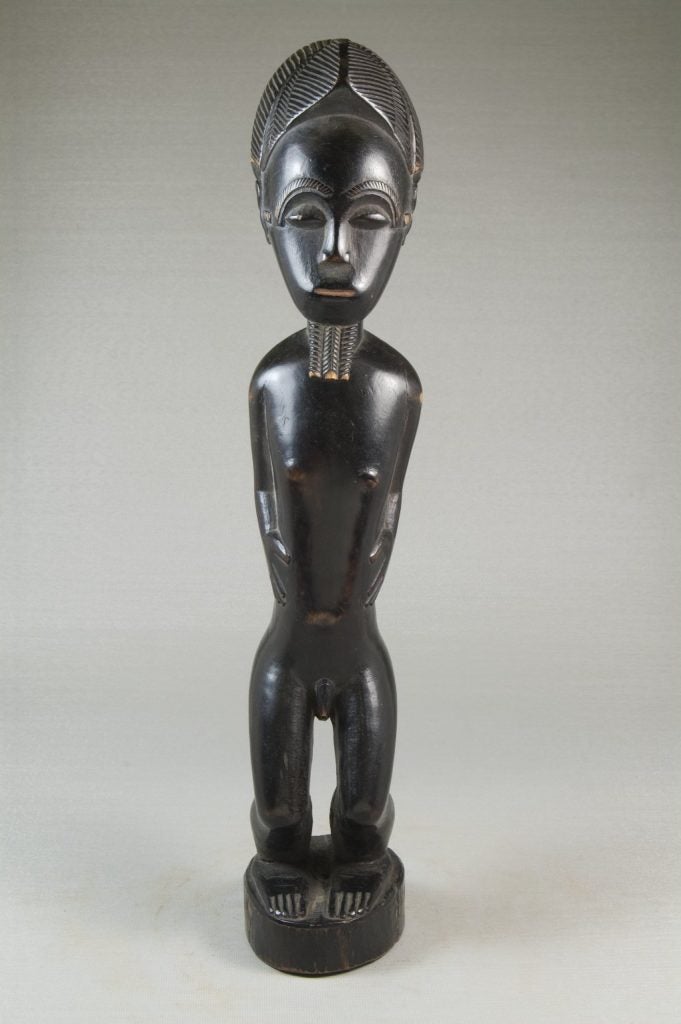

In the late 19th century and first decade of the 20th, the ideal husband was an older, successful farmer. He was an established provider and might be indulgent if wealthy. Blolo bian from this period indicate age through a beard (Fig. 242), here carefully plaited. This particular example has facial features that echo those of some Baule masks: large, half-closed eyes, pronounced brows that join with the narrow line of an elongated nose, and a small mouth. The lower body probably would have been partially covered by an actual loincloth. Although from approximately the same time period, a second male spirit spouse (Fig. 243) is clearly by a different artist. Because of ephebism, the face remains wrinkle-free and the well-developed calf muscles indicate vigor, yet it too depicts an elder, recognizable only by his neatly tied-off beard. The hair is carefully incised and dressed, and scarifications at the temple, neck, and torso beautify the body. A loincloth probably covered this figure as well. Head-to-body proportions are similar in both figures, as are their balance of rounded calves and buttocks.

Some other early spirit husbands showed greater status by taking a seated pose (Fig. 244). Again, dignity and serenity are stressed, the powerful calves belying an incipient belly that demonstrates wealth. Like the other examples, the engraved lines that constitute the hair speak to careful grooming, and conjoined brows and nose demonstrate a tie to the art of other Akan peoples to the east.

After the French colonized the Baule area, many changes transpired, not least of which was a new economy. While farmers certainly remained good providers of nourishment, new desires arose as novelty goods from overseas appeared in the markets and shops. These were part of a new economy, an economy that required French currency for both acquisition of new types of imported goods and the payment of taxes. How to gain French currency? Trading with or working for the French. Interaction with these foreigners required knowledge of their language; the greatest financial opportunities came to those who could join their civil service, a profession that required education in foreign schools and subsequent literacy. One might not marry a civil servant with all of his accomplishments and benefits, but one’s spirit spouse could be a man of such achievements.

By the 1920s and 1930s, many male blolo bian were representations of beardless younger men. Some wore elements of Western clothing, such as a pith helmet and suit, along with Baule facial scarifications. Forced conscription into the French military system In WWI and WWII also became a source of foreign exchange, and uniformed spirit spouses (Fig. 245) continued the trend toward spirit husbands with carved clothing. This continued into the 1950s and 1960s, expanding to include depictions of sportsmen (Fig. 246). Despite dramatic shifts in the ideal man, his grooming continued to be a critical factor. His earlier long hair and intricate beard might be shorn, but the sharp cut-in part and stylish pompadour reflect updated desirability in a new era.

Female spirit spouses display far less variation over time. Although there are some examples from the 1960s on that show women with fashionable dresses or permed styles (Fig. 247), most female representations continued to show a nude woman, sometimes pregnant or breastfeeding, or simply alluding to her fertility by placing her hands on her abdomen (Fig. 248). Her hair is carefully dressed, her facial, neck, and torso scarifications precisely handled, and real beads sometimes ornament her (Fig. 249). The blolo bla‘s adherence to less-changing standards may speak to men’s gender expectations from their wives, spirit or human (Fig. 250). Occasionally, however, a spirit female has appeared with a typewriter, speaking to her literacy, worldliness, and earning power.

More women have recourse to a spirit spouse than men, perhaps because fertility issues are most often attributed to them, or because polygamous homes present rivalry issues that can exacerbate spousal conflicts. Figures are intimately associated with their owners; they can become unimportant if they have not aided in solving the owner’s problem, or if the owner dies.

Baule sculptors also create figures that begin as virtually indistinguishable from spirit spouses, yet represent a completely different type of being from the supernatural world: nature spirits (asie usu). These are conceived of as extremely ugly beings from the bush, carved in an ideal form in order to flatter and placate them. These spirits dwell in the wild, but may maliciously attack those who interact (albeit unintentionally) with them–often hunters or farmers. They inflict illness or other problems and can even possess their human host. A diviner may pinpoint a client’s problems to a nature spirit, and advise a “portrait” of the figure be created and honored. Analogous to spirit spouse figures, the nature spirit will communicate through dreams with artist, patron, or diviner what his or her desired appearance should be. It variously occupies its figure or its owner, who may become a diviner because of their accommodation of one another.

Spirit spouses are caressed, washed, and handled, their food offerings contained by plates or bowls. Nature spirits have sacrifices poured over them, and are rarely touched. Despite these different interactions and the resulting differences in patinas, without collection histories, it is virtually impossible to distinguish the figures of nature spirits and spirit spouses because of their treatment after collection. Early 20th-century French collectors preferred gleaming surfaces, and often removed–not just from Baule works–sacrificial patinas, polishing the cleaned items and making it difficult to reconstruct their usage. Some nature spirits are represented by couples (Fig. 251), which alleviates the puzzle, while others still have something of their original sacrificial patina. Without these clues or information about a specific object’s use at the time it left Côte d’Ivoire, a Baule figure’s function remains uncertain.

Further Reading

LaGamma, Alisa. Art and Oracle: African Art and Rituals of Divination. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

Ravenhill, Philip L. Dreams and Reverie: Images of Otherworld mates among the Baule, West Africa. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996.

Vogel, Susan M. Baule: African Art Western Eyes. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997.

Vogel, Susan M. “People of Wood: Baule Figure Sculpture.” Art Journal 33 (1, 1973): 23-26.

Love in the Age of AIDS

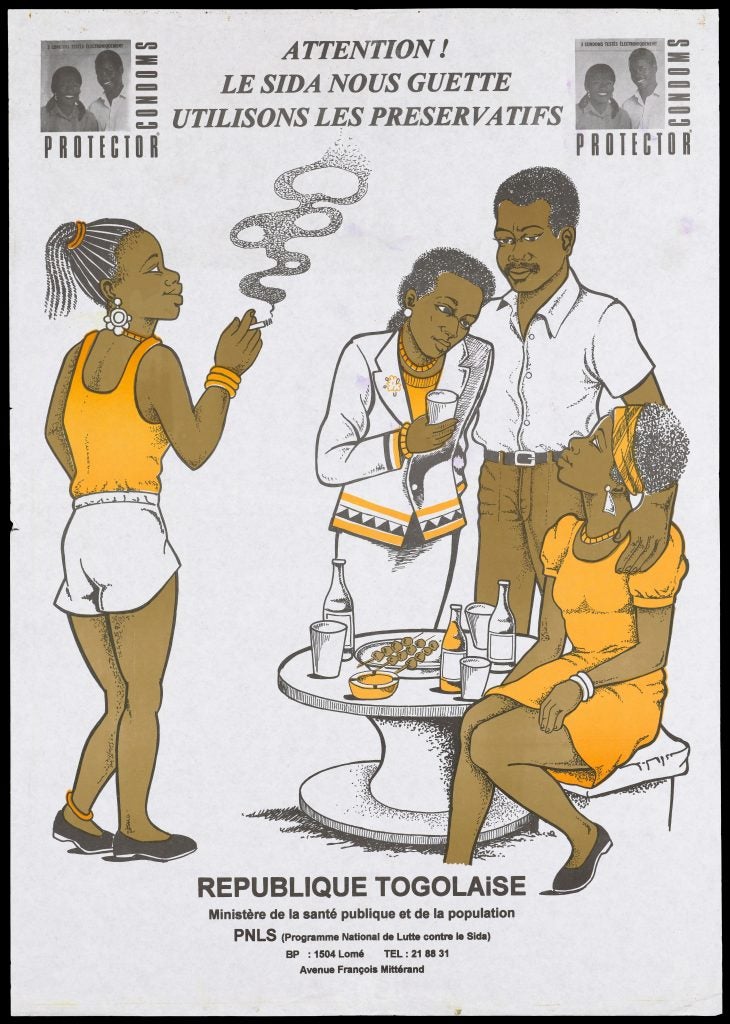

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS in English; SIDA in French) and its HIV-positive predecessor were first recognized in Africa in the early 1980s, quickly becoming a pandemic that affected all parts of the continent, but became particularly prevalent in southern African nations. Public health management was a necessity in order to change behavior, prevent its spread, avert isolation of those affected, and draw attention to medication and other management procedures. Many different educational initiatives arose, from banners in Lagos’ international airport that read “Stay protected–wear a raincoat” (a euphemism for a condom) to illustrated leaflets and posters. The latter were particularly encouraged, as they attracted attention and could be “read” by non-literate individuals (Fig. 252). This continuing effort has helped encourage and support African graphic designers.

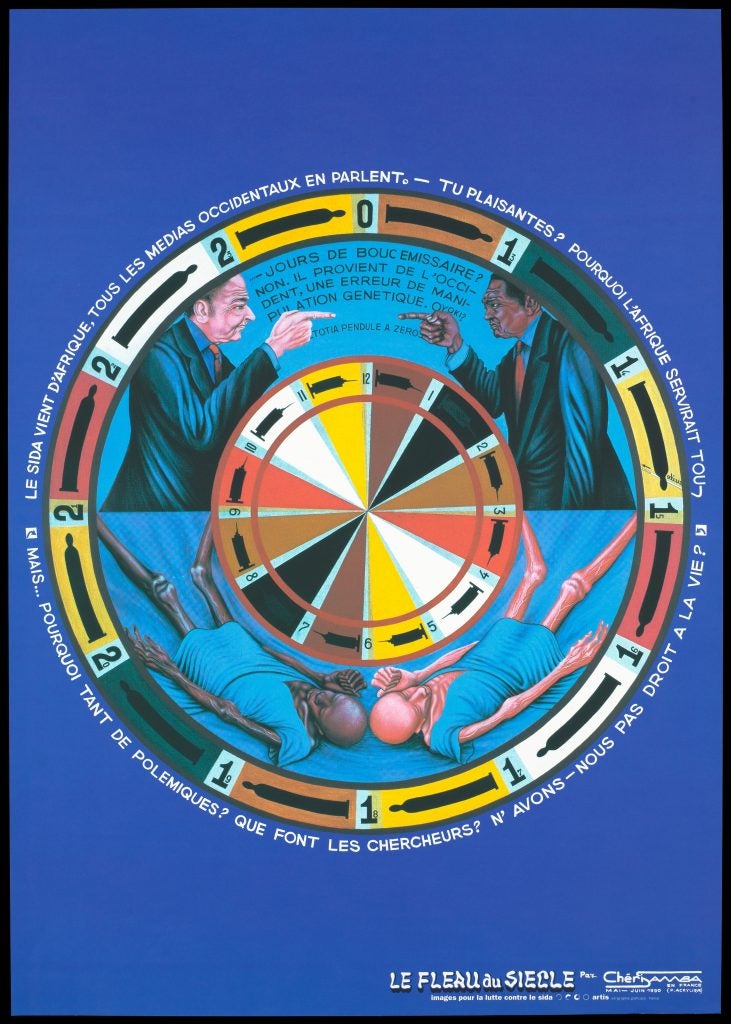

Numerous popular urban painters in the Democratic Republic of Congo have addressed both AIDS itself as well as issues of infidelity that cause its spread. Chéri Samba and his younger brother Cheik Lédy (who died of AIDS in 1997) both addressed these issues in their paintings, amidst other themes that deplore corruption, winks at sexual matters, and salient observations about urban lives. Samba created a poster for an exhibition on AIDS-related art in 1990 (Fig. 253). The inscriptions–a familiar inclusion in Samba’s paintings–refer to the argument between European and Congolese officials. Where did AIDS come from? The Westerner in the print states that the disease came from Africa: “all the Western media say so.” The poster’s African counterargument: “Are you joking? Why is Africa always scapegoated? No, it’s been proven to be from the West, an error of genetic manipulation.” The painting is set up like a dartboard with two dials, one bearing condoms, the other syringes. In the board’s lower half, two emaciated AIDS patients, their complexions the inverse of the men in suits, wonder: “But . . . why all the polemics? What are the researchers doing? Don’t we have a right to life?” Samba’s style, on the border of realism and caricature, often illuminates social issues dealing with issues of male/female behavior, or–in this case–their consequences.

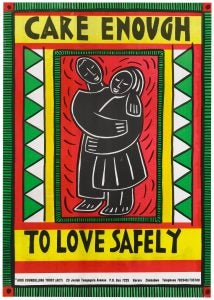

Concerns about the effects of infidelity are reflected in both commercial and personal art forms. Numerous works stress family responsibilities or a loving relationship as a form of protection (Fig. 254). A professional designer created this example, and it is meant to be eye-catching through its use of bright, saturated colors and clear message.

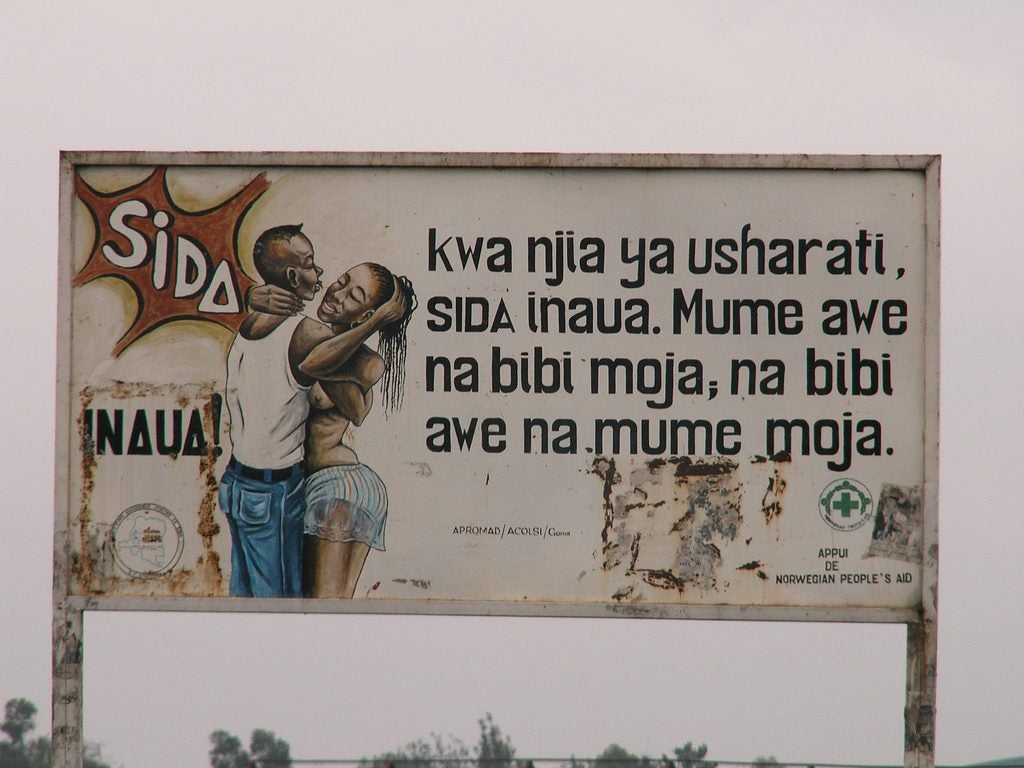

Urban artists create some of the public signage meant to reduce AIDS, and they often stress avoidance of prostitutes and the use of condoms. The ways in which these artists characterize males and females tend to concentrate on transactional couples (Fig. 255). This billboard’s fairly naturalistic imagery dwells on the woman’s exposed breast, transparent skirt, and makeup, although the man remains fully dressed. Salacious imagery is meant to draw the male viewer’s attention, but the cautionary message takes up most of the composition, perhaps out of concern the viewer might miss the overall import in favor of a seductive focus.

The “original couple” of Adam and Eve may be the reference for the central motif on a wall in Gabon (Fig. 256). Bucolic nature scenes with wild animal signifiers flank what appears to be a foreign couple gazing at each other longingly under a tree. They seem to be a tropical, updated (and more discreetly clothed) version of Adam and Eve, the white dove hovering over them suggesting the presence of the Christian Holy Spirit. Their presence is distinctly tied to the concept of temptation–though mangos, rather than apples, are the forbidden fruit–since the inscription above them states “Conscience controls desire.”

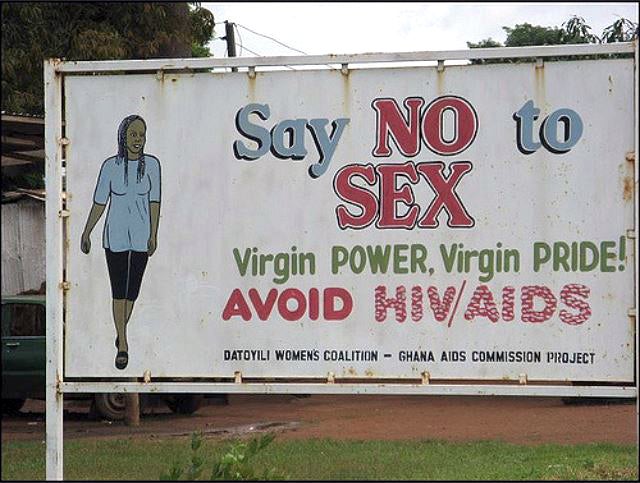

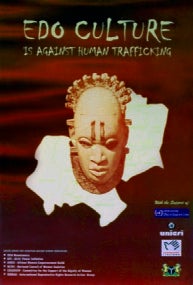

Visual efforts to curb the disease often encourage girls to remain chaste (Fig. 257), often harking back to regional social mores of the past, which may have since become antiquated within their respective cultures. The artist who painted this billboard has clothed his virgin in attire that would have been considered scandalous not long ago–tight bicycle shorts might prove a deterrent to access, but long or short pants were considered provocative in many regions through the 1990s. The power of past traditions is even put to use to discourage young women from being lured into the European sex trade (Fig. 258), with the 16th-century face of Queen Mother Idia directing a stern look at any young women who might be contemplated departures from traditional moral codes.

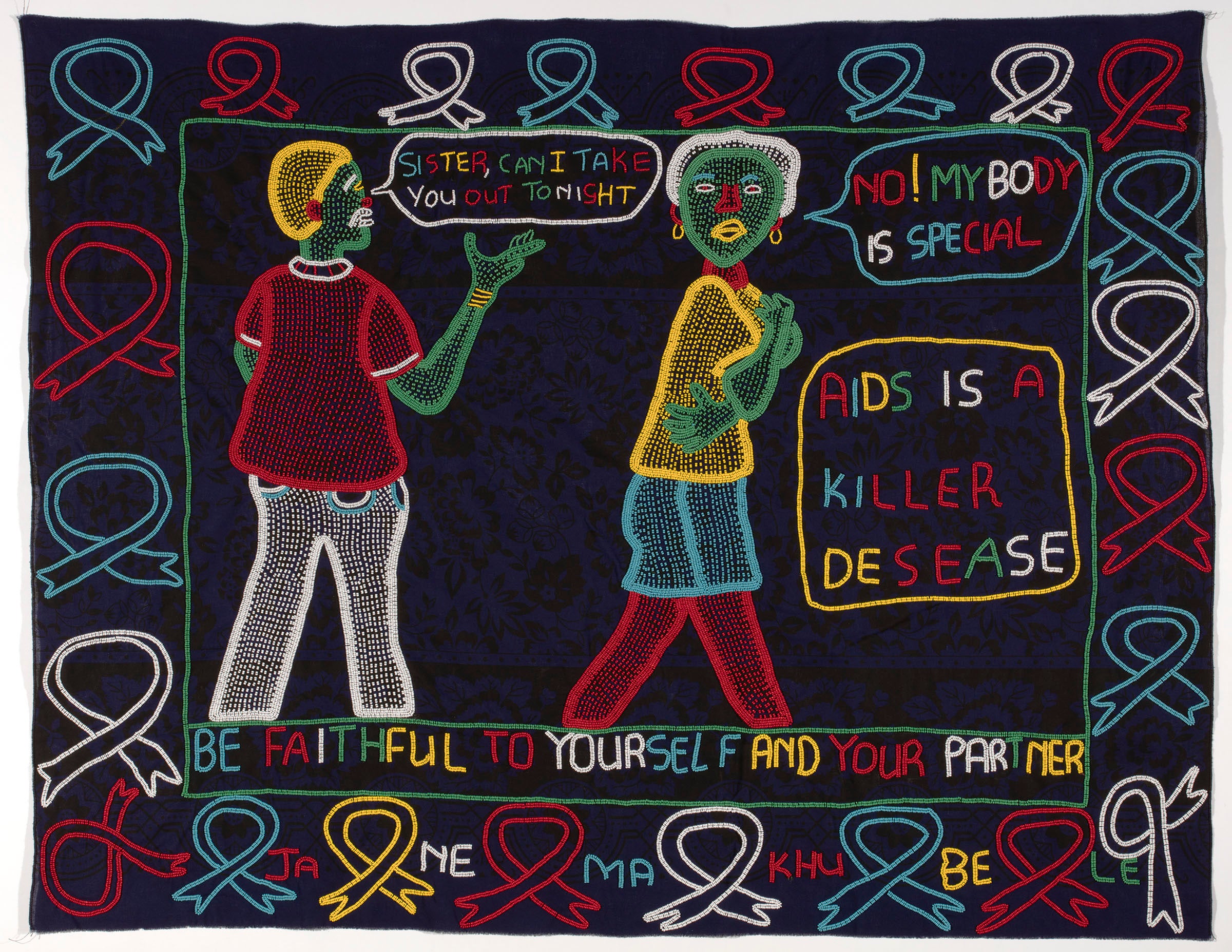

More personal is a beaded wall hanging by Jane Makhubele, which speaks to a chaste young woman who is protecting herself from potential disease (Fig. 259). The central image is bordered not only by beaded versions of the red HIV/AIDS ribbon, but by turquoise, yellow, and white versions as well. These integrate the work’s colors, although the red ribbon is the symbol meant to promote awareness of the disease and solidarity with those affected. Many South African female producers of beaded souvenirs include the red ribbon on dolls that depict married Zulu women (Fig. 260). Here the ribbon appears on the doll’s beadwork, a message perhaps exhorting all couples to remain faithful.

Further Reading

Adéjùmọ, Àrìnpé Gbékèlólú. “Family health awareness in popular Yorùbá arts.” In Toyin Falola, ed. Africans and the politics of popular culture, pp. 261-274. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester, 2009.

“Les artistes africains et le SIDA = African artists and AIDS.” Revue noire no. 20 (March/April, 1996): 82-83.

“Les artistes africains et le SIDA = African artists and AIDS.” Revue noire no. 21 (June/July, 1996): 82-90.

Lunda, Violet Bridget. “Of abstinence, virginity and HIV AID: the language of female empowerment in Botswana advertisements.” In Susan Arndt, Susan, ed. Theater, performance and new media in Africa, pp. 187-200. Eckersdorf, Germany: Breitinger, 2007.

Melville Herskovits Library of African Studies, Northwestern University Library. “Communities Uniting to Fight HIV/AIDS in Africa” online exhibition. 2002.

Njogu, Kimani and Mary Mugo-Wanjau. “Art and health promotion: creativity against HIV and AIDS.” In Kimani Njogu, ed. Cultural production and social change in Kenya: building bridges, pp. 187-213. Nairobi: Twaweza Communication, 2007.

Roberts, Allen F. “‘Break the silence’: art and HIV/AIDS in KwaZulu-Natal.” African Arts 34 (1, 2001): 36-49, 93-95

.