Chapter 3: Themes in African Art

Chapter 3.3 Motherhood

To be a mother marks female social completion in Africa. Without it, one is not quite an adult, or certainly not an adult who receives full respect. As Chapter 3.7 indicates, without children one cannot have a traditional funeral nor become an ancestor. While these issues relate to men as well as women, infertile men can acquire children through cooperative wives who ensure they become pregnant; women do not have that option. In practical terms, women who are not mothers may be divorced or have to accept a co-wife. They have no support in their old age, for that is the duty of children, and–if their husband dies–they even may not have a place to live. Even those who are wealthy and self-sufficient suffer if childless. Even those who are unconcerned about financial support or ancestorhood have to endure the pity or mockery of family members, friends, and acquaintances. Babies born after a longed-for conception often bear names that reflect their mothers’ anxiety. These Edo names from Nigeria’s Benin Kingdom are among many examples that reflect joy, triumph, and satisfaction in a successful delivery after the pain of barrenness. They pointedly refer to previous distress and are meant as retorts to those who might have tried to block their pregnancy or had made fun of them: Oghiomwanghaghomwan (“When one’s enemy looks at one”), Omoigiate (“Child protects one from shame”), or Aganmwonyi (“A childless person has no glory”).

Training to be Mothers

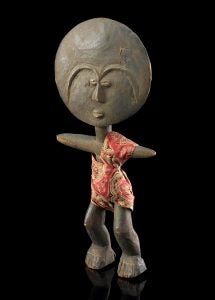

In many parts of the continent, girls have received doll-like figures to care for–not as playthings when they are children, but as teenagers preparing for marriage (Fig. 261). This sometimes occurs during initiation practices, when their attentiveness may be assessed. Several related matrilineal groups from Tanzania share the tradition of mwana hiti (Fig. 262), a figure a girl receives from a female relative in her father’s family before her initiation seclusion. Alone in a small structure, it serves as her sole companion, and she “feeds” it, washes and oils it, decorates it with seed beads at neck or hips, and otherwise tends it like the infants she hopes to have. All mwana hiti are female, as their breasts indicate, since female children are especially desirable in order to increase the size of the matrilineage. Upon completion of initiation, she emerges

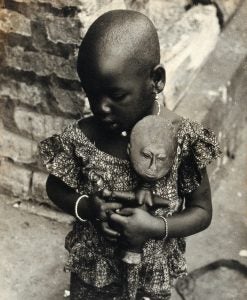

to dance, the figure tied around her neck. In the early 20th century, teenage Zulu girls used to carry dolls (Fig. 263), often attached to a cord worn over their shoulder. They initiated romantic relationships by gifting a favored boy with the doll; when apartheid formally began in 1948 and many sweethearts were separated because of migrant labor, young women in the countryside would have studio portraits of themselves holding their dolls, which they would then send to their boyfriends in the city–an effort that created a fictive family for him to concentrate on concerning future marriage plans.

Searching for Motherhood

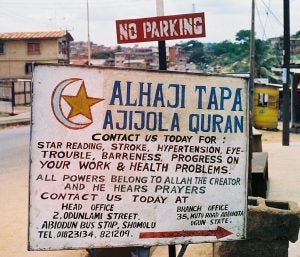

Women with conception problems frequently seek help from Western physicians, diviners, and ritual specialists (Fig. 264) or through intercessions with ancestors, deities, or other entities. Sometimes general visual exhortations to fertility exist; rulers’ stools in the Cameroon Grassfields region usually include animal references, and the frog–symbol of fertility and general increase–is a common motif (Fig. 265), since the royal household must grow as well as those of his subjects.

This huge Baga masquerade, known as D’mba (Fig. 266), depicts an older woman who has suckled many children, her breasts now fallen and flattened. Not considered a denizen of the spiritual world, she epitomizes womanhood. Although she appears at the deaths of the prominent and at important secular occasions, D’mba appears in conjunction with agricultural activities and weddings, which suggests general fertility associations. Women throw rice (the chief crop) at her, and men and women alike slap her breasts, a gesture said to enhance fruitfulness.

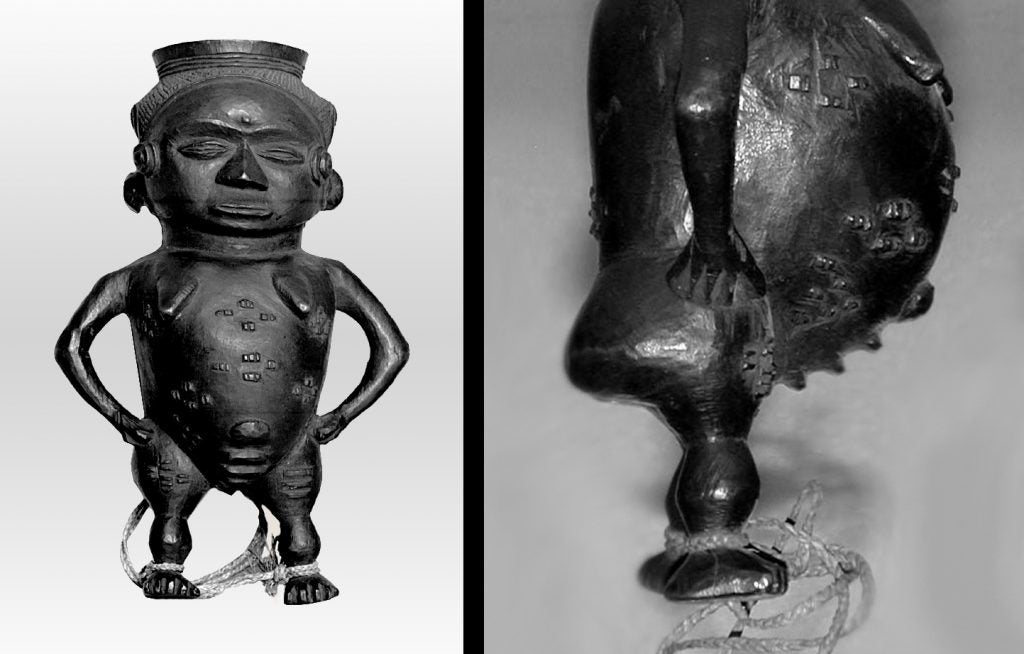

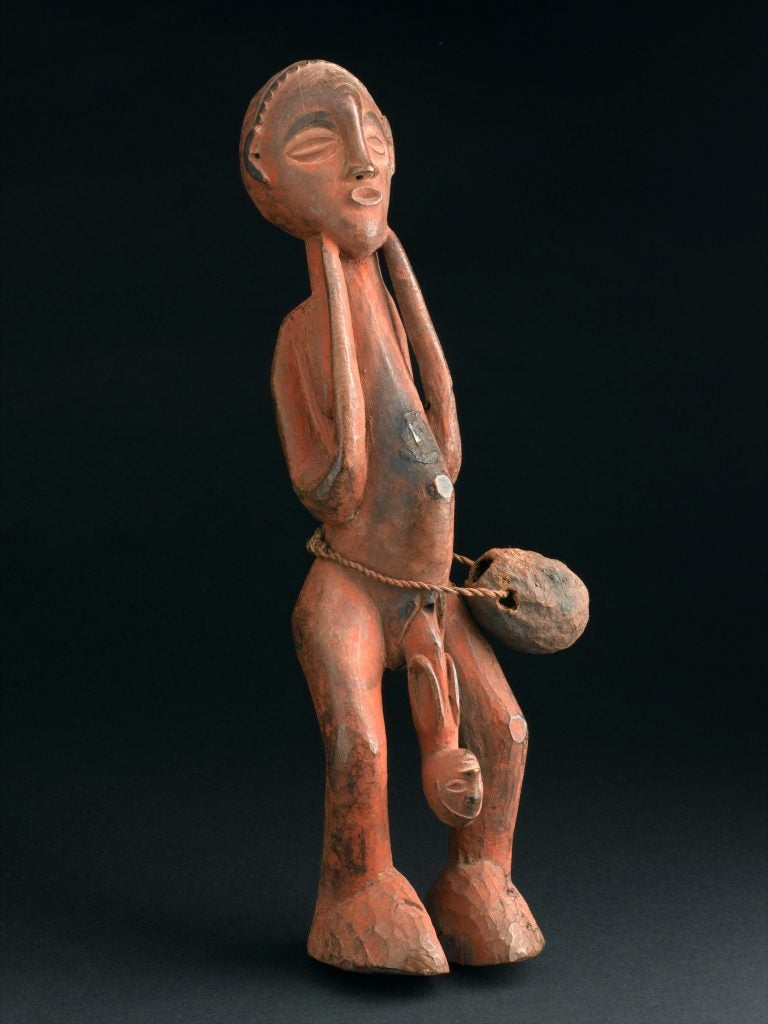

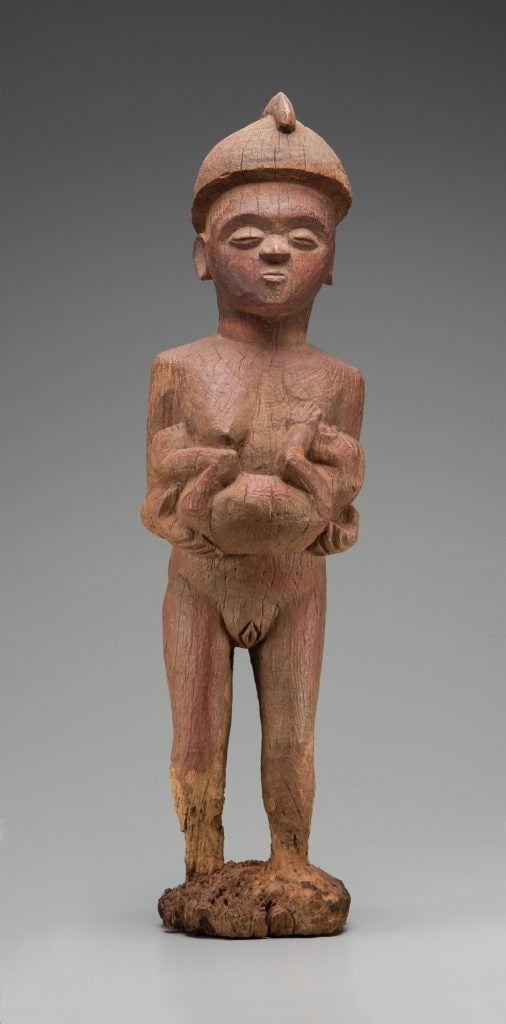

They might travel to shrines of great repute in order to redress the issue. A particular Kongo nkisi figure (Fig. 267), its activating medicines (see Chapter 3.5) originally sealed off with a mirror, was probably meant to aid those seeking pregnancy. These figures, which may take male, female, or animal forms, are carved to house a spirit of the dead who will do the bidding of the living; medicines placed in a torso cavity and sealed with a mirror or a shell activate the work, and are prepared to specific recipes that match the power figure’s specific intended purpose. Unless the information about function was recorded at the time of collection, we don’t normally know a figure’s goal. However, in this example, the mirror seems to have lost its silver backing and we can see into the cavity. The medicines within the female figure (her hairstyle indicates gender) include kaolin chalk carved into the form of a mother with a baby, among other ingredients, suggesting fulfillment through maternity.

In southern Ghana, Akan women (including the Asante and Fante) who had difficulty

conceiving went to priests who might suggest they have an

aku’aba figure (Fig. 268) carved and blessed They then carried it tied onto their backs like a real baby. The figures were female, since Akan society is matrilineal, and the family grew and thrived with the birth of girls. They are stained dark, with heads that are usually oversized, circular, and extremely flat, dominated by a forehead that takes up at least half of the face. Most have abstract features consisting of an arching unibrow that unites with a small nose, little or no mouth being indicated. Eyes generally take a coffee-bean form. These features are similar to many of the terracottas used to represent the deceased at funerals (see Chapter 3.7). The flat, large forehead is considered a desirable physical trait, and mothers gently massage infant’s skulls to achieve this. Many aku’aba have long necks bearing a series of parallel, raised ridges; these are the artists’ interpretation of a natural phenomenon seen elsewhere in West Africa–natural creases at the front of the neck (though shown as encircling it) that are considered especially appealing. The oldest figures appear to have been heads and necks attached to a cylinder with tiny breasts. Later, stubby side-stretched arms became standard and then legs became a common feature (Fig. 269).

When pregnancy occurred, the prospective mother continued to carry the aku’aba in order to ensure her child would be healthy and beautiful, just like the figure. After a successful delivery, the mother might take the figure to the shrine where it was dedicated. An accumulation of such figures indicated the shrine solved infertility problems, and ensured other clients would feel reassured by its success rate. Some mothers, however, kept their figures and might give them to children as playthings. Although they did not begin their lives as dolls, that could be the end result (Fig. 270).

Figurative Christian aids to conception also existed. Catholicism has had a periodic impact on the Kongo since the late 15th century (see Chapter 4.2). Associated artworks include numerous crucifixes as well as Madonna images, but depictions of saints are clearly dominated by a particular individual: St. Anthony of Padua. While St. Anthony was born in Portugal, and it was the Portuguese who first brought Catholicism to the area, this does not explain his dominance, particularly since missionaries from many other countries came to the region. Although known in the United States as the saint who is entreated to find lost objects, his associations in Europe are quite different. He is implored by maidens who seek a husband, and–probably his chief attraction for the Kongo–his intercession will bring children to the barren. A church at the Kongo capital was named for him, as was a brotherhood of laypersons, and he appeared on pendants and other art objects. Usually depicted in his Franciscan robes, holding the infant Christ and a book (for Christ would appear to him while reading), his image would have stood in Kongo churches or homes as a focal point for prayers for pregnancy. The museum that owns one example (Fig. 271) recorded that it was handed down within a family and used “in fertility rituals.” St. Anthony was so venerated that a Kongo female royal, Dona Beatriz, claimed she was his reincarnation when she made a bid to reunite all the Kongo kingdoms under her leadership in the 18th century.

Woman as Vessel: Pregnancy

If numerous art forms to encourage pregnancy exist, images of pregnancy itself are less common. Sometimes sculptures allude to gravidity by showing a woman’s hands on her gently swelling stomach, but late pregnancy is occasionally depicted. This Wongo palm wine cup (Fig. 272) is likely a visual pun linking the concept of woman as a container to an actual vessel.

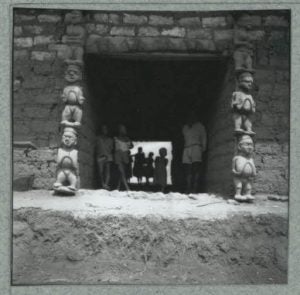

The one area where unambiguous pregnancy is actually unexceptional is the Grassfields region of Cameroon, home to numerous related ethnic groups. Here a palace door surround’s imagery might solely consist of pregnant women (Fig. 273) and freestanding figures often represent the same condition (Fig. 274).

Two far-flung ethnic groups, the Yoruba and the Makonde, perform masquerades by male dancers performing as pregnant women. These are not the focus of either performance, but represent one human type among many roles. The dancers from both cultures accomplish this by wearing not only a headpiece, but a body plate that includes both breasts and belly (Fig. 275). Both are lifelike in proportion, offering a smooth expanse that can be enlivened by tattoos or scarification, depending on the origin (Fig. 276). Makonde examples occasionally even include the linea nigra, or pregnancy line, for greater verisimilitude.

Parturition

Depictions of imminent or actual childbirth are fairly rare throughout the world, and have been so throughout history, although exceptions certainly occur. In Africa, these can show the partial emergence of the child, whether in the

constructed setting of a maternity clinic, as in some Igbo mbari houses, or as stand-alone figures such as this Zombo sculpture (Fig. 277). The latter realistically shows the remaining swollen belly, the facial expression stylizing the pain of the moment in a gesture the neighboring Chokwe use to indicate surprise. Sometimes delivery is merely part of the panoply of life a multi-figure work includes (Fig. 278).

Some of the most unusual childbirth scenes have been found at the deserted city of Jenne-Jeno in Mali, unfortunately without context since they were excavated illegally. One shows a woman delivering a snake (Fig. 279), her mouth in an atypically stretched rictus of pain. Another snake emerges from one ear, and breakage suggests an additional serpent exited the other ear as well.

Snakes appear with great frequency in the terracotta sculpture of Jenne-Jeno. Sometimes they appear to attack individuals, squiggling aggressively over their bodies and heads. At other times, an individual has a snake or snakes resting on them, yet their posture shows only co-existence and indifference. The snakes suggest the powers of a ritual specialist that may be sent out after a victim or stay at hand, waiting for a task. That a woman is giving birth to a snake, however, seems outside this interpretation unless we are witnessing a mythological occurrence or a snake as the representation of a person of power. There has been a suggestion that certain Jenne-Jeno images, this included, relate to the Sunjata epic and the founding of the Mali Empire. If so, the snake may represent Sunjata’s birth.

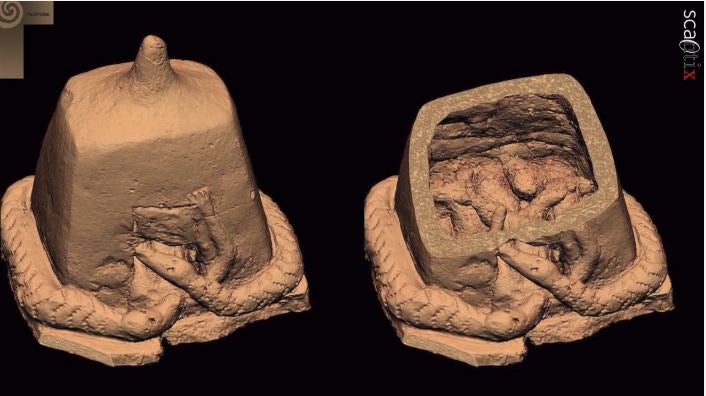

Certainly mystical snakes appear in other Jenne-Jeno terracottas in connection with human sacrifice. One snake is shown with human feet sticking out of its mouth before a final swallow–the size ratio indicating an unnatural occurrence. Another depicts a shrine or other structure encircled by giant serpents who are about to enter; a human arm reaches out from the sealed door (Fig. 280). Medical imaging revealed that the interior of the building is neither solid nor hollow. Instead, it is filled with seven small decapitated clay female figures, several of whom are pregnant.

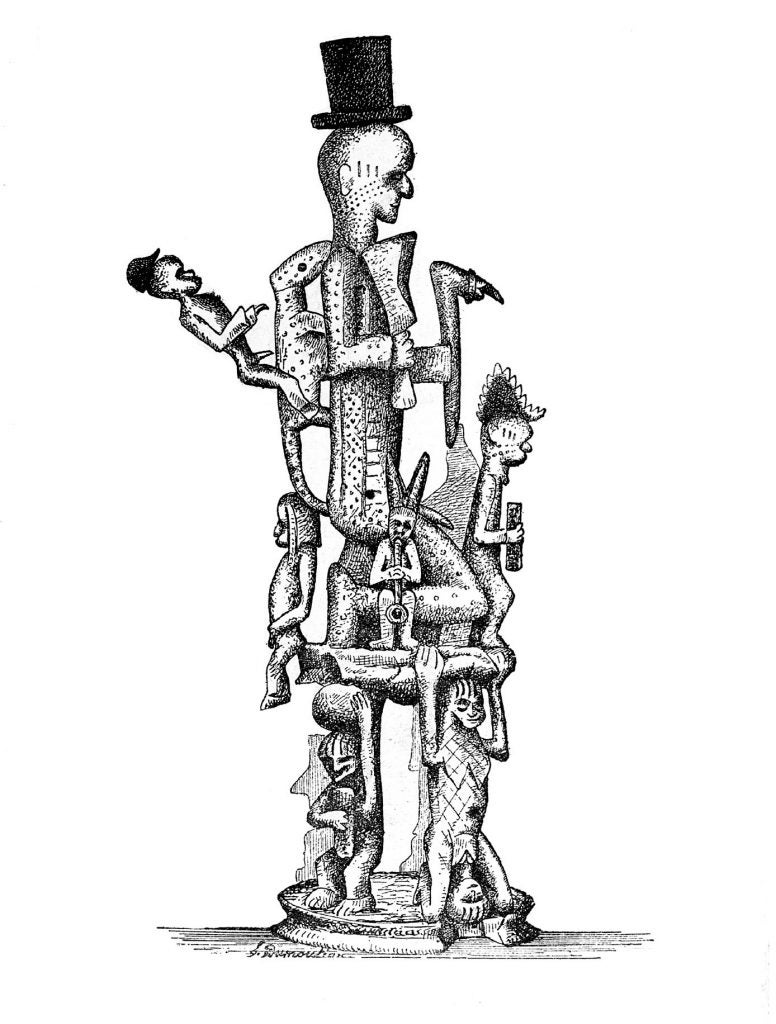

Yet another Djenne sculpture depicts one of the most unusual subjects in African art (Fig. 281). Not only do we see a woman about to give birth, stretched out horizontally, we see her in the company of her husband, who supports her shoulder and bends solicitously over her; he is non-frontal. In most African cultures before the advent of Western doctors, it has been traditional to exclude men from the birth process. Either a midwife or experienced woman assists in birth; some women have given birth on their own, particularly if away from others at a farm. If these features were not enough to make the work distinctive, when at a New York auction house to be put up for sale it was discovered that the tiny figure of a baby was placed inside the “womb,” suggesting the work may have had a mystical purpose related to childbirth–invisible aspects of African artwork are often related to ritual practices.

Mother and Child

Maternity figures are among the most common sculptural types found in Africa, attesting to the critical importance of motherhood. Their various functions may differ, but there are relatively few variations in pose and activity.

Many depictions show breastfeeding, the child held in the arms (Fig. 282) or on the lap (Fig. 283). These two figures have distinct uses: the Eastern Pende example was probably flanked one of the doors of a high chief’s kibulu ritual structure, a place of great secrecy that was inaccessible to most. She (along with a second figure, probably male) was attached to a panel and served as a spirit sentry to protect the ruler from malevolent rivals. The presence of the child shows she is a complete, mature woman. Slightly larger sculptures can decorate the kibulu roof peak; these can take many forms, but since the mid-20th century the maternity figure has been the most popular. The Bamileke figure served a different purpose. Although some similar figures commemorate important individual women in the royal family, those works normally include more jewelry to emphasize their status. This figure appears to have been brought out at court whenever twins were born. Their presentation before the sculpture was accompanied by a sacrifice. Twins are viewed as having special powers of good fortune and healing, and, after infancy, one was sent to the palace to serve the ruler (among the neighboring Bamum, both were sent). There twins had multiple roles, including special participation in a ruler’s installation of a ruler and as guardians of the royal burial sites. Their parents took on a special title, operating as priests or diviners.

Despite the physical bond of breastfeeding, most sculptures that depict it show figures who are not looking at one another, a feature shared with most other maternity images. This does not imply any actual lack of interaction or affection, but is merely a convention to convey dignity and self-control. The rarity of mother and child eye-contact makes its occasional appearance startling (Fig. 284). This dynamic sculpture does portray a seated royal

woman nursing, yet she turns her body towards the baby and looks directly at him, creating a sight line that unites them even more than her encircling arm and breast milk. Like many Bamileke works, it is infused with vigor, here created by the non-frontal posture, asymmetry, and the series of

diagonals created by the thighs and lower legs, the lifted foot, and the bent arms. The energy created by the lines can be seen from every angle, and the not fully smoothed surface adds to the work’s vitality. This sculpture was created by a known artist–Kwayep–on the ruler’s commission. It depicts one

of the royal wives first child for the monarch, and would have been commissioned not just because of any affection he may have felt, but because Bamileke rulers were not fully recognized and allowed to use their title of “Fon” until they had had a son and a daughter while in office. Statues of royal wives and mothers were exhibited outside the palace during major court ceremonies, and possession of sculptures and other art objects added to the status of the Fon.

Sometimes the identities of mothers are ambiguous. While the nursing mother in a Senufo sculpture may appear to represent a human mother, some Central Senufo maternity figures represent Katyeleeo or Maleeo (Fig. 285). This Great Mother/Ancient Woman is the female aspect of deity whom the Poro men’s society honors during initiation (including a passage through a tunnel likened to her birth canal). As members of the Poro, they may state that they are “about their Mother’s business.” In works from this tradition, the “child” is the initiate, drinking in the Great Mother’s wisdom.

That is not, however, the meaning of all Senufo maternity images. The Fodonon Senufo (for the Senufo, spread out over three countries, incorporate many distinct populations such as the Fodonon) have a female secret society known as Tyekpa that acts as a counterpart to Poro. Like Poro, Tyekpa plays a significant role in its members’ funerals, a time when sculpture enhances the prestige of the deceased and the women’s society to which she belonged, just as it does for male funerals where Poro officiates. Tyekpa figures, which are comparable in size to Poro sculptures, are carried aloft by members and displayed; multiple figure types are not restricted to a nursing mother, but these are a common category. It is unclear whether the Tyekpa nursing figure (Fig. 286) represents the Great Mother or not; some other Tyekpa figures represent champion farmers, young women, and other members of the citizenry, and she may be a human mother.

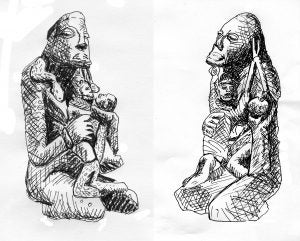

Incomplete information hinders understanding of some maternity figures. Although many may be indications of the value placed on fertility, others, such as Senufo Poro figures, do not refer to human mothers at all. While the Jenne-Jeno terracotta figure of a woman bearing a snake may be human–albeit with a supernaturally-charged “child”–another Jenne-Jeno figure seems likely to be an otherworld being (Fig. 287). Initially, this sculpture may appear to be an ordinary kneeling mother with two slightly older children scrambling over her, but one of the children has a beard and wears trousers–they are clearly adults, despite their juvenile behavior. The mother remains impassive, despite the snake crawling over her shoulder–her nonchalance seems to speak to her familiarity with spiritual forces. Her hold on dignity is challenged by the fact that she is not frontal; her head inclines slightly to one side, for each son grabs the handle of a forked implement that grasps her ear. The instrument is a blacksmith’s pincers, the tool he uses to grip and draw red-hot metal.

The identity of this huge woman who towers over men, enfolds them in her protective embrace, and suffers their antics is uncertain. Because of its location along the Niger River, Jenne-Jeno was an important walled trade city that drew multiple ethnic groups and was part of both the Ghana and Mali Empires. Occupied by at least 200 BCE, it was deserted ca. 1400 for reasons that remain unclear, and a new town of Jenne arose less than two miles away. We don’t know the ethnicity or gender of the terracotta artists, nor if they departed from the immediate area or converted to Islam and stopped making figures as a result.

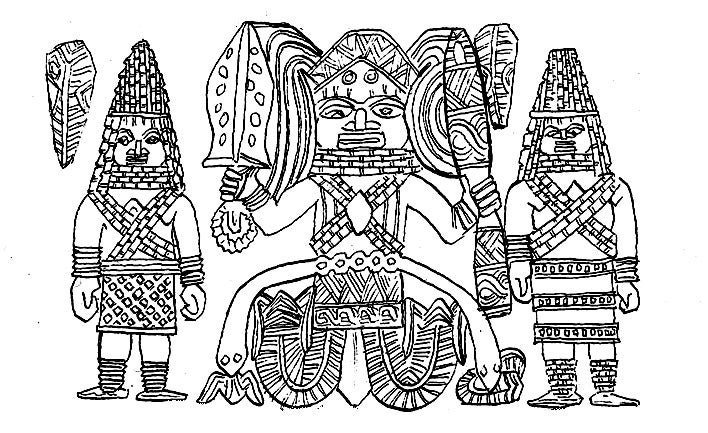

Some scholars see stylistic links between the terracottas of Jenne Jenne and works by Dogon artists (Fig. 288), who live about 128 miles away. Although oral history states the Dogon migrated to their present home centuries ago, their linguistic relationship is with the Senufo and other Gur language group members to their south. Jenne today is home to Songhai, Bozo, Bamana, Fulani and other peoples; the Bozo and Bamana are Mande peoples, and blacksmithing has special associations to them, as well as to their Gur and Senufo neighbors. All these regional ethnicities are casted societies. Smithing is a hereditary, casted profession with associated social roles involving spiritual powers and supernatural manipulation, and seems to have been in place by the 13th century, perhaps coalescing at the beginning of the Mali Empire. Mande blacksmiths state they have an origin that differs from that of other Mande, and, although they speak Mande, they retain their own vocabulary in a distinctly different tongue.

Could this Jenne-Jeno sculpture refer to mythical beginnings for blacksmiths? Bamana and other belief systems about foundational myths vary from region to region, and deepen as one advances within men’s societies, but some of the many stories about primordial beings refer to Muso Kuroni, the original woman, a creator who also embodies chaos, and who is identified with sorcery. Ndomajiri, the first blacksmith, is also the stuff of myths, the stable counterpart of chaos and master of ritual medicine. While we cannot be certain that this female figure is somehow the “Mother of the Blacksmiths”, that she is a spiritual entity with some kind of blacksmith connection is supported by evidence within the piece itself. Knowledge of its original placement–a shrine? a blacksmith’s forge?–would have provided further context, but unfortunately is unretrievable.

Most maternity images, even when they represent otherworld entities such as Baule spirit spouses, are more generic in appearance. Women are shown with children as evidence of their completion of adult responsibilities and their assured place in the world.

The appearance of their children is an accessory that proves their worth and reinforces their status; the child is a necessary but minor player in the visual world. Children may be held laterally (Fig. 289), sit on the lap, be on a hip (Fig. 290), or be carried on the back (Fig. 291). Most children find backing soothing, as they can hear their mother’s heartbeat clearly. While many babies are silent accessories, artists assign others greater prominence. Carved Yoruba babies seem interested in the world around them, frequently straining against their carrying cloth in order to obtain a better view (Fig. 292).

Most images of mothers with their children show them either as infants or toddlers, and are formal in their poses. Some of the earliest depictions of mothers, however, depict a range of children’s ages, as well as clearly playful behavior and interaction. A Sahara rock painting, for example, shows a crawling child as well as his older companions. Despite the silhouette approach, their body language conveys actions and interactions still visible in every family (Fig. 293). Other Sahara images from the same era show a mother laying on her back, raising her child up in an exuberant gesture, or two juveniles standing next to an adult and holding hands.

Another notable exception to maternity imagery is found in Nigeria’s Benin Kingdom. While its Edo royal court artists did represent the Iyoba, or Queen Mother, in ivory and brass, she was usually sculpted either alone or with her girl pages. She appears with her son only on the ivory tusks that decorated royal ancestral altars (see Chapter 3.7), but he is depicted as a reigning adult, not as a baby or child. She flanks her son, her image duplicated to preserve symmetry (Fig. 294). Her presence is protective; on some other tusks, she holds mystical mirrors that deflect harm directed at her son. Other kinds of maternity images did not occur in Benin court art, although the large unfired clay images that form altars to Olokun, the deity of the sea and riches, often represent one or more of his wives holding a baby (Fig. 295), a more conventional way of showing the maternal bond and continuity of the lineage, whether human or supernatural.

Further Reading

Blackmun, Barbara. “Who Commissioned the Queen Mother Tusks?: A Problem in the Chronology of Benin Ivories.” African Arts 24 (2, 1991): 54-65, 90-91.

Bouttiaux, Anne-Marie and Marc Ghysels. “Scrofulous Sogolon: Scanning the Sunjata Epic.” Tribal Art 19 (2, no. 75, 2015): 88-123.

Cole, Herbert M. Icons: Ideals and Power in the Arts of Africa. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989.

Cole, Herbert M. Maternity: mothers and children in the arts of Africa. Antwerp: Mercatorfonds, 2017.

Curnow, Kathy. At Home in Africa: Design, Beauty and Pleasing Irregularity in Domestic Settings. Cleveland, OH: The Galleries at CSU, 2014.

Drewal, Henry J. and Margaret Drewal. Gelede: Art and Female Power among the Yoruba. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1983.

Felix, Marc Leo. Mwana Hiti: Life and Art of the Matrilineal Bantu of Tanzania. Munich: Fred Jahn, 1990.

Gagliardi, Susan Elizabeth. Senufo Unbound: Dynamics of Art and Identity in West Africa. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2014.

Glaze, Anita. “Woman Power and Art in a Senufo Village.” African Arts 8 (3, 1975): 24-29, 64-68, 90-91.

Grunne, Bernard de. Djenné-Jeno: 1000 Years of Terracotta Statuary in Mali. Brussels: Mercatorfonds, 2014.

Homberger, Lorenz, ed. Cameroon: Art and Kings. Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 2008.

Jolles, Frank. African Dolls/Afrikanische Puppen: The Dulger Collection. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2011.

Lamp, Frederick. Art of the Baga: A Drama of Cultural Reinvention. New York: The Museum for African Art, 1996.

MacGaffey, Wyatt. Astonishment and Power. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993.

McNaughton, Patrick R. The Mande Blacksmiths: Knowledge, Power, and Art in West Africa. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1988.

Ross, Doran H. “Akua’s child and other relatives: new mythologies for old dolls.” In Elisabeth L. Cameron. Isn’t s/he a doll?: play and ritual in African sculpture, pp. 42-57. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1996.

Sieber, Roy and Roslyn Walker. African Art in the Cycle of Life. Washington, DC: National Museum of African Art, 1987.

Strother, Z. S. “Eastern Pende Constructions of Secrecy.” In Mary H. Nooter, ed. Secrecy: African Art that Conceals and Reveals, pp. 156-178. New York: The Museum for African Art, 1993.

Thornton, John. The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684-1706. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998.