Chapter 3: Themes in African Art

Chapter 3.4 Art and Youth Initiation

Youth Initiation and Associated Practices

Many parts of Africa have no youth initiation. Zones that include it are concentrated in Central Africa, South Africa, parts of Africa, and far more limited sections of West Africa. Some areas that do include youth initiation involve associated art forms that are limited to body decoration and special dress. Others, however, involve masquerades, initiation objects, or decorated lodges.

Youth initiation marks a transition from childhood to adulthood, and typically began by removing children from familiar surroundings where they slept with their mothers, their close playmates limited mostly to relatives. They are frequently plucked from this environment abruptly, often under circumstances they find mysterious and frightening, and swept away to an initiation camp situated in the wilderness or “bush”, a place they have always been warned to avoid due to wild animals and frightening spirit inhabitants. Although each gender encounters initiation in its own camp, usually during a different time period, they share an abrupt, painful beginning to the experience: circumcision for boys and excision (sometimes referred to as female circumcision) for girls. These operations signalled a symbolic death of participants’ childhood.

Though performed by experts, these operations are completed without anesthesia or painkillers, a traumatic event that serves to bond those who undergo it. Many members of the cohort may have been virtual strangers before initiation, but this first exposure to the wider world of community introduces the participants to the citizenship that will be part of adulthood.

Some areas where female initiation was once common have abandoned it due to international pressure regarding excision, often called female genital mutilation (FGM), a procedure involving the removal of some (part of the clitoris), most (clitoris and labia minora and/or majora), or all of the external genitalia. By 2016, the United Nations reported that excision was illegal in twenty-eight of Africa’s 54 countries. Illegality is not always been enforced, however, and social and marital pressures in favor of excision are particularly strong in some parts of the continent, and immaterial or never applicable to others. Circumcision is legal everywhere, and practiced nearly universally, whether in infancy or during initiation.

Male initiation does not necessarily occur annually, so the ages involved vary. Generally, initiation takes place between the ages of 8 and 18, though circumstances may extend these bracketing ages. Time spent in the camp now takes several weeks; in former times, it extended over a period of months or years of isolation from the larger community. After healing, boys’ education began. Training incorporated oratorical prowess in the use of proverbs, vocational education in carving, farming, weaving, fishing, or boys’ education began. Training incorporated oratorical prowess in the use of proverbs, vocational education in carving, farming, weaving, fishing, or other skills, sex education, the creation and use of supernatural and practical medicines, local history, psychological management of the opposite sex, and instruction in esoteric matters. Upon completion of their education, the initiates were reintroduced to society, their orientation now directed toward the world of men and fellow initiates.

One of the major male initiation zones cuts across a large swath of Central Africa, sweeping across many ethnicities in the Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Angola and Zambia. Masquerades are a major feature of initiation in this area, and performers were involved

in snatching the boys from their homes to the camps, training them, fetching food from the initiates’ mothers, and reintroduction of the boys to the community. Among some groups, such as the DRC’s Yaka (Fig. 296), the initiates themselves wear masks upon their graduation. They, too, often include references to sexuality or to proverbs.

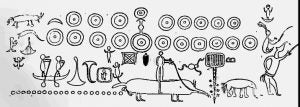

At this stage, some ethnic groups such as the Nkanu (Fig. 297) created stall-like display elements near the camps; these are no longer made. Their elaborate background graphics have symbolic meanings, acting as a mnemonic device for initiates that include references to virility and fertility. Other motifs are leadership symbols or refer to daily life.

Chokwe Male Initiation in Angola, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo

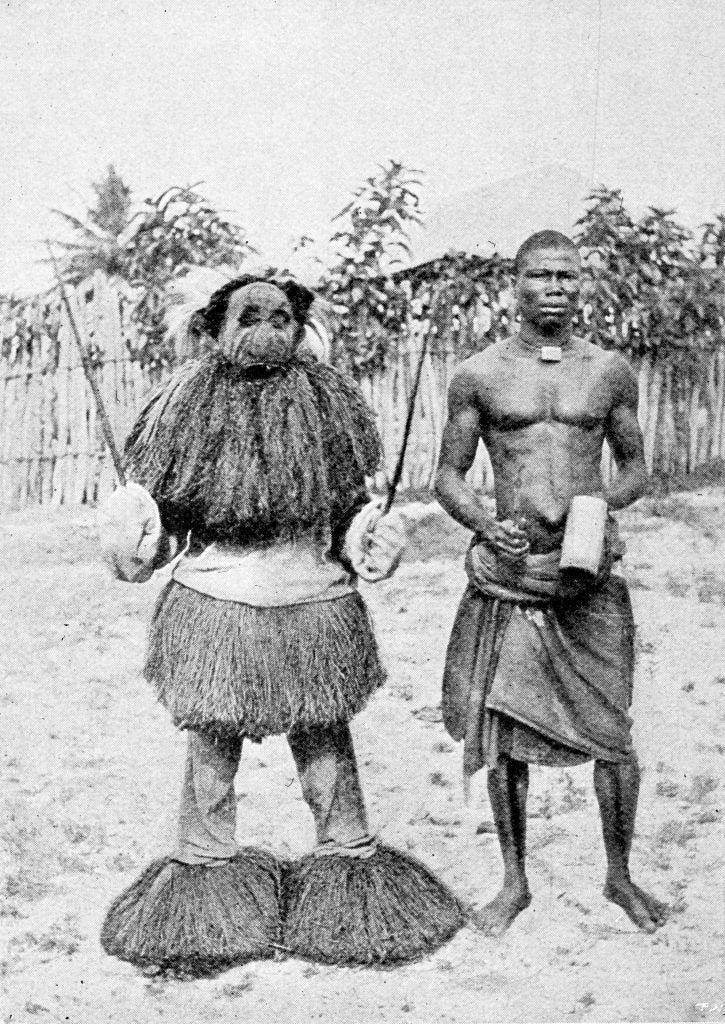

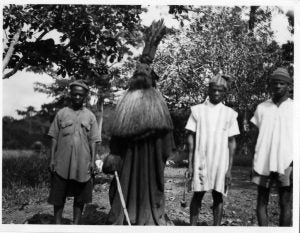

The Chokwe are one of a number of peoples that once formed part of the Lunda Empire, and, like many of their neighbors, they practice male youth initiation that incorporates masquerade performances. Male initiation requires that boys, whose orientation has been strictly towards their mothers and family members, be snatched from their familiar environs and taken to the bush, a fearful place they have always been warned against. This is not usually an annual event; the initiation process (mukanda) depends on the local demographics, economic circumstances, and the decisions of elders. When the catchment of boys of the appropriate age (about 8-15 years old) from neighboring villages is deemed adequate, male society members will prepare the initiation camp. The removal of the initiates is not immediate; their families will recognize the advance signals, although the children will not. Masquerades enter the villages and perform, then leave. Some time later, certain masqueraders will return and carry the boys away to their symbolic “death”.

These initiation masquerades (mukishi) (see video below) include numerous stock characters that are described as ancestors. Some have human traits (the chief, the beautiful maiden), while others represent protective and sometimes aggressive spirits whose human qualities are less evident. For example, Fig. 298 (known as chikuza) bears a tall, phallic-shaped projection and is compared to a particular kind of grasshopper of the same name with a similarly extended head. It functions as the camp leader, protecting the camp and the boys, and it has further associations with successful hunting and fertility. Miniatures of this mask often appear in divination baskets.

Before boys are initiated, they believe these figures are spirits; one of the secrets their initiation makes them privy to is the fact that men make and perform the masquerades, and they too will learn how to do so. Before this and other layers of knowledge are revealed, however, the newly-arrived boys go through a painful introduction to manhood: circumcision. Their first few weeks at the mukanda camp are quiet, for the boys are believed to be vulnerable to malevolent forces, as well as health risks. They sleep in pens bound tightly by upright sticks so they cannot turn in their sleep and injure their healing penises. Their ordeal bonds them to fellow initiates, some of whom had been complete strangers. As the weeks go on, older men begin to train them in occupational tasks, as well as verbal abilities, sex education, psychological management techniques, and other skills they will need to be adult males and useful citizens. In addition, they learn complex dances, a secret pictograph system, and other esoteric knowledge. They are subject to absolute discipline. They do not leave the camp, which is regarded as a living being whose

body is its wooden retaining wall, with “eyes” made of shaped vegetation that project upwards, and “ribs” made from additional projections. The circular enclosure’s one entrance is closed off at night, and the boys are circumscribed by multiple rules, including a single place for urination. The masqueraders go back and forth to the village to collect food for the boys from their mothers, an act that not only provides sustenance but reassures the women that their sons are alive and well.

A designated circle within the camp is the area where the masquerades are made and kept. The netted costumes are crocheted from bush fibers, and the masks themselves are made by stretching barkcloth (felted by beating the bark of a particular tree) over a reed framework, sealing it with resin, then painting it, typically in black, red, and white. Some of the masks are extremely large, but the materials keep them lightweight. Because these masks are not carved, however, their facial features are not crisp, nor can they always attain complete symmetry.

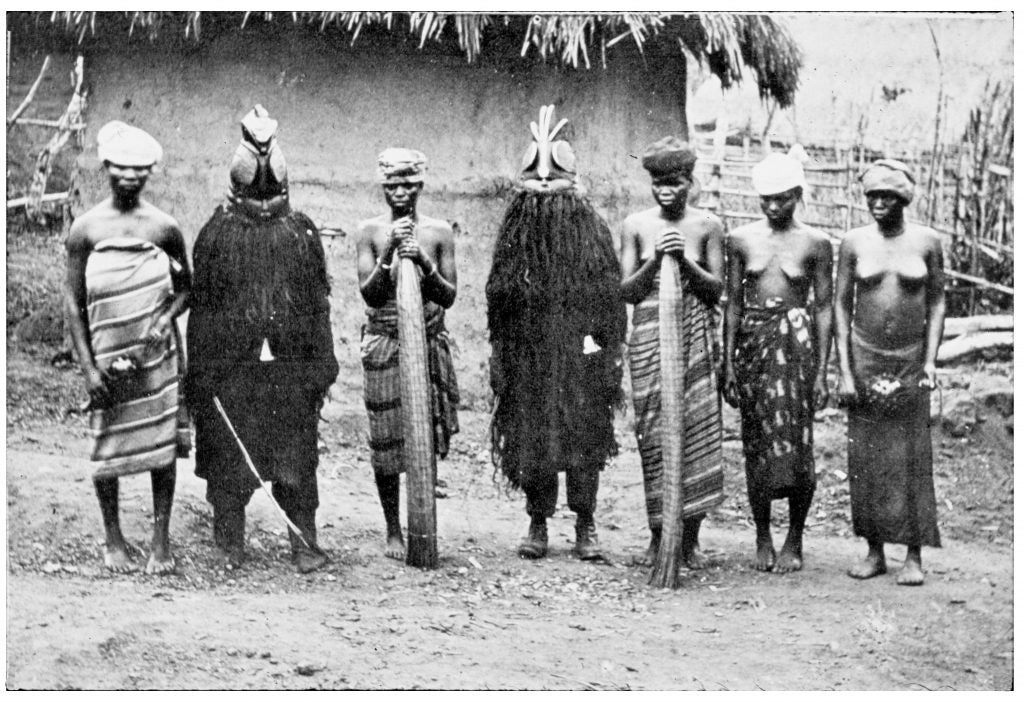

The chihongo mask (Fig. 299) represents a Chokwe chief. Although the performer’s arms and chest are encased in a tight crocheted shirt,

a cloth wrapper (a sign of towns and civilization) covers their lower limbs. In contrast, many non-humanoid mukishi wear full raffia skirts at the waist. Two prominent features of the chihongo mask are the large semi-circular projection from the jaw and the large curving headdress (Fig. 300). These can also be seen in wooden masks that depict the chief (Fig. 301). In wooden versions, the semi-circular section is cantilevered from the chin, jutting out horizontally. Despite its rigidity, this form indicates the beard of an elder in both wooden and bark/resin examples. The curving headpiece, here made from feathers, imitates the curving form of the crowns Chokwe chiefs once wore (Fig. 302). The masks’s eyes typically are conceived of as coffee bean forms set into deep eye sockets that connote age. Wooden masks were once worn by the chief himself or a designated male family member; along with a “female” masquerader (performed by a male), it went from village to village collecting taxes. After the respective colonial governments banned the practice, since they wanted the taxes themselves, wooden masks switched functions and were used for entertainment dances. Some mukanda

camps employ a few wooden examples now, but resin/barkcloth versions are still more typical.

When training is complete, the initiates are reintroduced to their communities. They enter in initial silence, escorted by the masqueraders, dressed in uniform style with hats and decorative patterns on their faces, arms, and torsos (Fig. 303). They sit in state, bowls in front of them to collect appreciation money from well-wishers. They later dance and interact with the townspeople, accepted as those who have put childhood behind and are now oriented to adulthood and the world of men. They will no longer sleep in their mothers’ houses.

After the initiation season has concluded, senior men set the camp alight, burning it and the barkcloth masks; wooden examples, if in use, are taken away and stored until the next initiation.

Female Initiation among Cross River Peoples, Nigeria

In southeastern Nigeria and neighboring border areas of southwestern Cameroon, girls underwent initiation, albeit in their own homes, rather than a bush camp. The main peoples who held this tradition were the Ejagham, Efik, Efut, Boki, and Ibibio, although some of the easternmost Ijo and southeastern Igbo who bordered the Ibibio practiced it as well. Although this initiation practice has not entirely disappeared, its occurrence has been severely impacted by both the impact of Christianity and state laws in Cross Rivers State (though not in Akwa Ibom state, home of the Ibibio, nor the Igbo states) and a 2015 federal law that have banned excision. Virginity tests at the outset of seclusion are an affront to some participants, and initiation’s coming-out ceremony requires bared breasts. Christians frown on body exposure; girls have also been convinced this is a backwards practice. Excision marked the beginning of initiation, and enforcement of the laws is somewhat spotty–nearly half the Ejagham aged 15-49 are said to have undergone the procedure. Because it is illegal, however, and initiation is so closely identified with it, the public face of initiation has been sharply diminished or even vanished in some areas. In others, however, it continues without including the now-controversial operation.

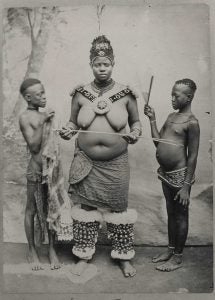

In the early 20th century through the 1970s, however, Cross River female initiation was common (Figs. 304, 305). A special room in the initiate’s household was prepared for her seclusion; if she had a sister or cousin also being initiated, they might share a room to alleviate boredom. This room was referred to in English as the fattening house. Although girls in the same area might begin the process simultaneously, they did so in their own compounds, usually acting as a group only at the outset and conclusion. Initiation usually began when a girl was about 12 or 13 years old (although it could take place later), and might continue from for several weeks or several years–even up to seven–depending on the family or fiancé’s wealth. Among some groups, fiancés were permitted to visit initiates, who might give birth while in seclusion, but other ethnicities insisted on virginity until seclusion ended. Sometimes a particularly well-loved bride might be returned to the fattening house after the birth of her first child, to return her to robust health. In the last quarter of the twentieth century, it was usually abbreviated to a period of about five weeks.

During the fattening house period, girls’ lives changed abruptly. From a very active life that required them to perform multiple chores–including fetching water for the household repeatedly on a daily basis–they were encouraged to sleep and rest, their only exercise the dances they were taught to perform. Meals that had been reasonable but light on meat became rich feasts that were served throughout the day, with herbal medicines administered to aid digestion. If a girl had not yet reached menarche, this lifestyle shift often prompted it. Daily life became a combination of instruction from elderly women who went from house to house to visit the initiates, feeding, sleeping, practicing dancing, and being pampered through massage, the application of white cosmetic kaolin clay or black vegetable dye in patterns, red camwood powder, hairdressing, and other traditional cosmetics. Instruction focused on child care, nutrition, and how to manage a husband, but also included some esoteric knowledge, folklore, and medicines. The regional practice of nsibidi, a pictographic system of communication, was sometimes inscribed on their skin–particularly the symbol for love and marriage (Fig. 306).

The vanished maidens not only grew physically and educationally, they underwent a period of rest and pampering unknown to small children and married women. Their skin grew pale from the absence of the sun, and they became mysterious objects of speculation. Dory Amaury Talbot wrote that Ibibio villages at the turn of the 20th century erected “bundles of frames” at the entrance to the marketplace, each one marking an initiate, so that strangers would know how many marriageable girls would be emerging. When the girls finally ended seclusion, they walked through the market, coiffed, made-up, and wearing jewelry and other adornments. Younger female relatives accompanied them as maids, fanning them and running errands. They held a new parasol to guard them from the now-unfamiliar sun’s glare, and received admiration and suitors. Many Efik women–even in the first decades of the 20th century–had studio photographs taken, since Calabar was a cosmopolitan enough city to support this trade.

Girls who had passed successfully through the fattening room were the pride of their families and the symbol of incomparable beauty and ideal

womanhood. While their rites were not usually accompanied by any arts other than body painting, jewelry, and hair designs–with occasional idiosyncratic drawings by the maidens themselves (Fig. 307) –they were the subject of numerous artists’ work in a variety of contexts. Ibibio girls carried dolls that represented initiates (Fig. 308) While their wide hips and thick thighs were emphasized, they do not actually represent corpulent women. Rather, the emphasis is on their youth and beauty, as well as their perfect coiffure. Ibibio puppets, used for adult entertainment, include the fattening house maiden as a stock character, often the subject of satyr-like pursuit in morality plays. Even Ibibio cloths that form part of funerary shrines can feature the initiates–whether to represent the deceased’s daughter, or just to beautify the textiles with her presence (Fig. 309).

The Ejagham and Efut peoples made some of the most elaborate and beautiful representations of fattening house girls. The former represented them in multiple forms: skin-covered helmet masks, often Janus or four-faced, that usually represented both males and females–the latter always with much fairer skin; skin-covered crests that could represent initiates at the peak of beauty (Fig. 310); and elaborate carved and painted headpieces that women supported on their heads during female society performances, their faces exposed. The crests were multi-media structures, the skin stretched over a wooden carving, and bone or cane depicting teeth that had been chipped, a fashion in the early 20th century. Multiple men’s societies used crests such as these, so without case histories, it is difficult to know exactly how a particular mask functioned, except to recognize the admiration initiates were held in, even in non-initiation contexts. Although the knack of making skin-covered masks died out in the late 20th century, some men’s societies still own old examples or make similarly carved and painted masks. In general, crest masqueraders dance in male-female pairs.

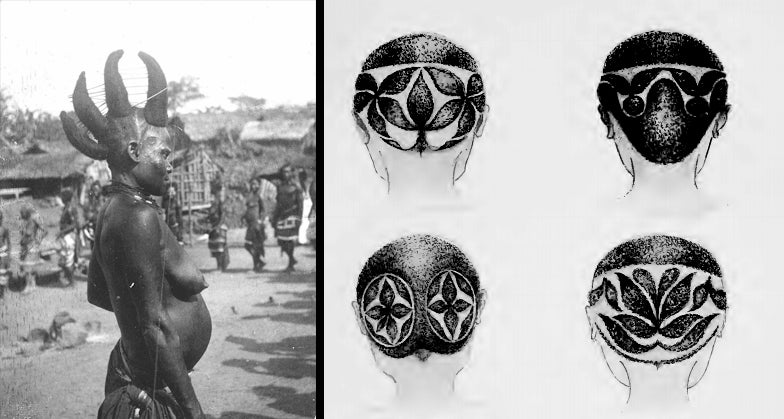

Efut crests can often be extremely naturalistic (Fig. 311), their skin gleaming like that of the oiled initiates. This work, in particular, adheres to human anatomy, the eyes fitting into a socket, the cheekbones rounded, and the mouth curving in a slight smile. The rows of holes along the hairline originally had inserted pegs representing hair wisps that had been rolled into balls. The elaborate hairstyles on skin-covered crests depicting initiates certainly seem exaggerated, yet the actual hairstyles worn by some Cross River women in the early 20th century make the inspiration clear. Horn-like coiffures could stand nearly a foot high, held upright by porcupine quills; sections of the hair were shaved to produced varied designs (Fig. 312).

Even among those who no longer retain the fattening house custom, some costume elements, such as the Efik use of elaborate brass comb ornaments, have been retained as traditional marriage attire (Fig. 313) or as part of folkloric costume for cultural dance troupes. Adaptations of the dances the maidens once learned for their coming-out now appear in cultural performances and music videos as expressions of heritage, as seen in the clip below.

Contemporary artists such as Victor Ekpuk, himself Ibibio, can still be inspired by the image of the lovely young woman. Like earlier artists, he has featured the silhouetted head of the mbobo initiate, recognizable by her distinctive hairstyles, in a series of paintings.

Male and Female Initiation in the Guinea/Sierra Leone/Liberia Region

Initiation for both boys and girls is still very prevalent in a band of ethnic groups in Sierra Leone and Liberia, as well as a corner of Guinea. The initiation societies continue long past youth, for a majority of adults belong to the men’s and women’s societies, and those who do not belong have something of an outsider status. Initiates to Poro, the men’s society, tend to be between 8 and 14, while those initiating to the women’s society–called Sande by the Mende and many other groups and Bondo or Bundu by the Temne–are usually closer to puberty. Initiations are not held annually, however, so some outlier initiates may be younger or older than the bulk of the group. Both groups are removed from their homes and taken to a bush camp, but initiations for both sexes don’t occur at the same time, and the camps are distinct from one another, with warnings along paths to members of the opposite sex to stay away.

Poro of Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea

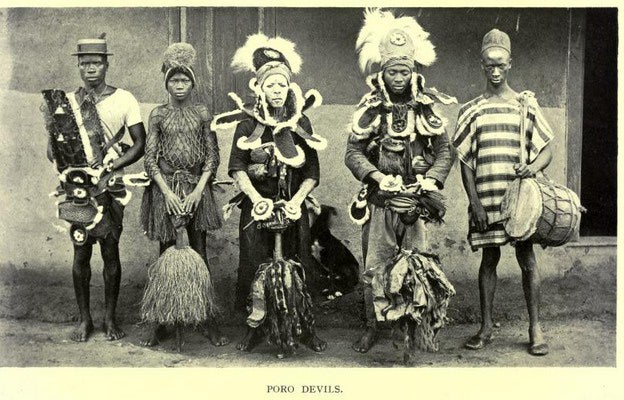

Like other male youth initiations, Poro begins with circumcision and a period of healing when boys are considered vulnerable to evil intentions, as well as possible infection (Fig. 314). Protective chalk (kaolin) is often applied to their faces and bodies, and instruction in verbal ability, professions, medicine, family management, esoteric knowledge, dance, and other subjects commences afterward. Multiple masquerades are associated with Poro, but they differ in appearance from one ethnicity to another. For the most part, these do not include wooden masks, but involve some kind of cloth and/or leather headpiece and a voluminous undyed raffia costume. They represent the spirits who embody the medicinal power of the society.

For the Mende, one of Sierra Leone’s biggest ethnic groups, gbini (Fig. 315) is the most highly-ranked of the masquerades. It appears at Poro initiations when the son of a paramount chief enters Poro, and it also dances at a paramount chief’s funeral. Its headpiece is modeled after a chief’s crown, a cloth and leather cap covered with talismanic amulets (Fig. 316). Its costume includes an apron-like section of leopardskin, and other pieces of leopardskin may form additional sections; like many parts of West and Central Africa, the leopard is particularly associated with rulership. Mirrors and cowries–the precolonial currency–often decorate the cloth further, the latter affirming its high status.

Goboi, another high-ranking masquerade, is similarly structured with a headpiece that imitates a chiefly crown, but it has a leather, rather than a leopardskin, apron. Wooden amulets bearing protective prayers in Arabic (for the Mende are predominantly Muslim) are hung on its back. While it also appears at paramount chiefs’ funerals, it participates in all Poro intakes and often also performs at cultural events (see 2017 video by Ngombu-Kabu below).

A number of lesser masks are also critical parts of the Poro system, such as nafali (Fig. 317), the messenger of goboi, whose headpiece is now made from cloth and yarn. Its quick dance steps are a particularly notable part of its performance.

The falui, a warrior spirit who sold one arm to further empower his medicine, wears a feather-topped conical cloth headpiece and a cloth costume embellished by raffia ruffs (Fig. 318), while the gongoli (Fig. 319), the only Mende Poro mask made from wood, is oversized and misshapen, often with swollen features. Considered ugly, it plays the role of a comedian, interacting with members of a crowd.

Other ethnicities with Poro include a variety of masqueraders. Those with wooden masks generally represent minor entertainment spirits, like the gela masks of the Bassa (Fig. 320) or the gbetu masks of the Gola (Fig. 321), which grow in a telescoping way when dancing. Both of these depict genderless spirits, yet the carved components are “female” with women’s hairstyles and delicate features, as are certain minor Poro masks worn by the Vai and other regional groups.

The only Poro wooden mask that represents a major spirit can be found among the Toma of Guinea (known over the border as the Loma in Liberia). This landai mask (Fig. 322) takes the shape of a composite animal, its ears, eyes, and nose taking human form, while its open maw is that of a crocodile, although fringed with fur, and its head is crowned with a tight bundle of feathers. This duality of animals and man represents the “great bush spirit” and a mythical founding ancestor, their combined wisdom and power guiding and protecting the society. The landai masquerader chews kola nuts that turn his saliva red; as this dribbles out from the mouth, it resembles blood. The masquerade snatches up boys when the time for initiation camp has come, sweeping them under the raffia and dancing them away to attendants, much to the boys’ alarm. Their menacing jaws and actions are referred to as “eating the initiates” who are said to die, only to be reborn after the completion of their initiation, their new scarifications said to have been created by landai‘s teeth.

The angbai (Fig. 323), another Loma mask, is also worn almost horizontally on the performer’s head. It similarly acts as an escort to initiates, although Neil Carey suggests it was used primarily for the second level of initiation that adult men participated in. This example’s extreme abstraction and simplification are typical. The mask required many rituals for consecration and originally may have been encrusted with a sacrificial patina.

During the 2014 peak of the ebola outbreak in the region, Poro and Sande initiations were suspended so that disease communication in the relatively close quarters of the sacred groves of the societies, as well as blood exposure due to circumcision, excision, and scarification, might be arrested. This suspension has since been lifted.

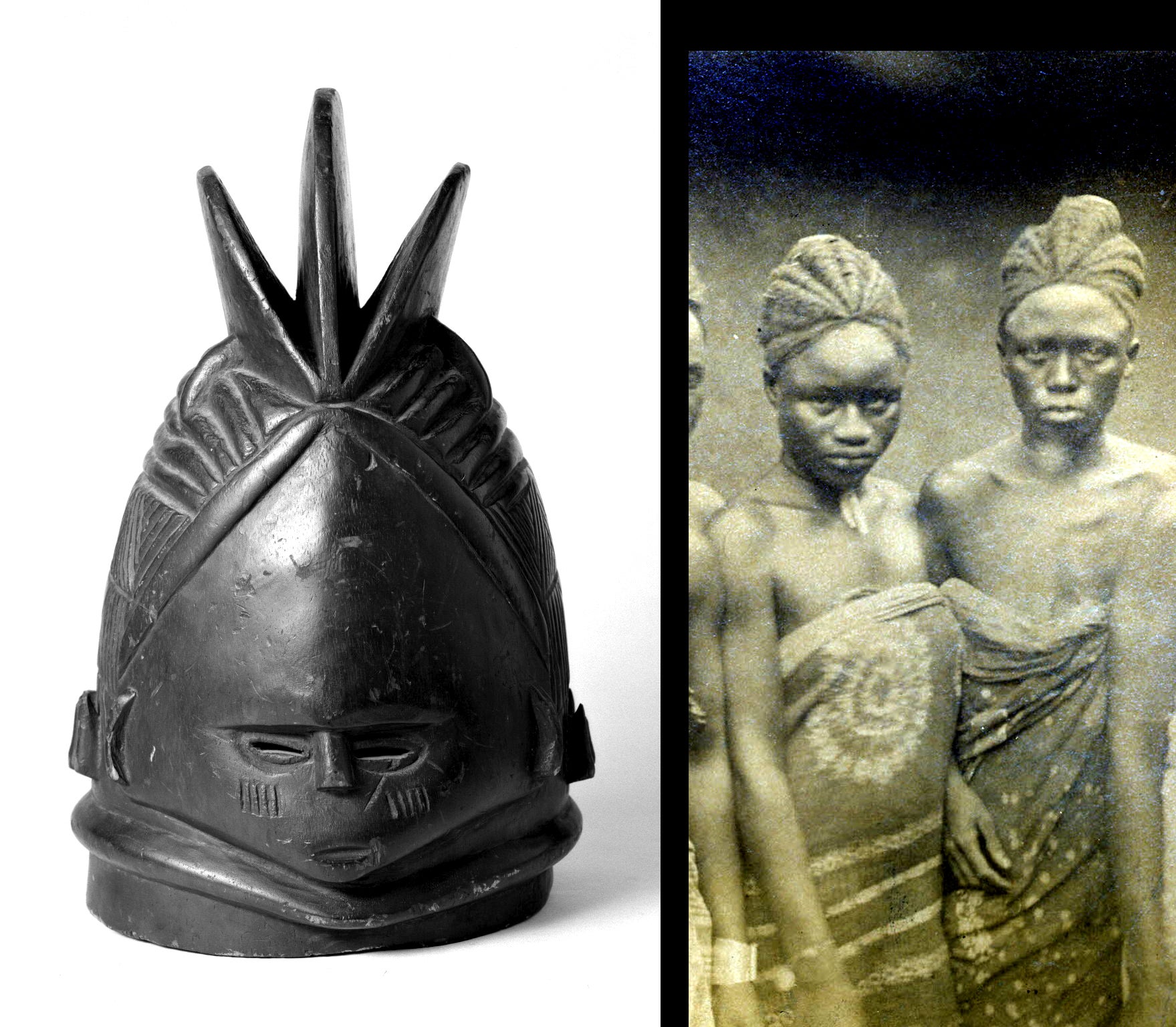

Sande and Bondo/Bundu of Sierra Leone and Liberia

The women’s secret society, known as Sande to the Mende and Bondo or Bundu to the Temne and Bullom and some other ethnicities, is Poro’s female counterpart. Although originally initiation took place at puberty, since 2007 Sierra Leonean laws have required participants be at least 18 years old. This not only encourages completion of secondary school, it permits acquiesence or rejection of the excision that remains the standard beginning of initiation. Unlike the disappearing practices of the Efik of Nigeria’s Cross River region, the Sande/Bondo groups are still very active. In 2016, UNESCO estimated that 89.6% of females between ages 15 and 49 were Sande/Poro members and had undergone excision, while the continuation of the practice was supported by 69.2% of women and 46.3% of men. Liberia’s situation is similar; 44.4% of the female population are from areas that practice Sande, and they have been excised.

The regional women’s society is unique in Africa, in that its tutelary female deity, a water spirit, is personified by a masquerader who is also female. Not fearful like the Poro masquerader, she (or they; an initiation camp can include several such masquerades, performed by exceptional dancers; see video below) escorts the initiates to their bush camp, keeps them company during their months of excision and training, and brings them back into town at the completion of their studies. These performers may also dance at civic or community occasions.

Although regional variations occur, the masks worn by performers are generally helmet masks (Fig. 324) that fit completely over the dancers’ heads. The wood is usually darkened with vegetable dye and polished to a sheen with palm oil or shoe polish, indicating well-cared for dark skin. Necks–thick, so the performer’s head can wear the mask–are creased, lines on the neck being considered particularly appealing (Fig. 325), much like Americans consider a dimple to be. Intricate hairstyles (sometimes archaic) are a hallmark of these masks (Fig. 326 ), inevitably reflecting the beauty of an ideal initiate.

Beauty is considered less of the happy accident of the features one is born with than it is the care and good grooming that any woman can employ to maximize attractiveness. Beauty is also exemplified by behavior. Researcher Sylvia Boone noted that the masks can be a teaching tool: ears are larger than mouths so that graduates might listen more than they speak; foreheads denote honesty and generosity, so they are portrayed as large and broad; modesty requires downcast eyes.

Like the Poro Society, Sande employs a special mask in its repertoire when a chief’s daughter is being initiated (Fig. 327). This example includes a European-style crown like those introduced by the British in 1896 as regalia for high-level Sierra Leonean chiefs; its projections also bear a resemblance to the flaps on the dancing costumes of Poro boys (Fig. 314). A parasol emerges from the top of its head; while Sierra Leonean chiefs do not generally use these, they are particularly popular among the Asante, whose paramount ruler the Asantehene lived in exile in Sierra Leone from 1896-1900, when he was transported to the Seychelles Islands. These large state umbrellas may have impressed Mende artists with a second royal symbol.

Sande also has a comic relief masquerader, just as Poro does. Called gonde, humor is associated with its performance, for it clowns with spectators and dances gracelessly, inverting the dignity, beauty, and the ideal image of the sowei. The gonde mask is usually an old sowei mask that has suffered termite or other damage and has been retired from its original function. It can be unevenly painted, negating its aesthetic qualities, or wear a multi-colored raffia costume, rather than the dark fiber of a true sowei. It can also be newly carved with deliberate asymmetry or other grotesque qualities (see a gonde image HERE).

Further Reading

Alldridge, Thomas J. The Sherbro and its hinterland. New York, The Macmillan Company, 1901.

Baeke, Vivian. “Let the masks dance!: circumcision among the Yaka, Suku, and Nkanu of southwestern DRC.” In Julien Volper, ed. Giant masks from the Congo: a Belgian Jesuit ethnographic heritage, pp. 58-79; 87; 147-151. Tervuren, Belgium: Royal Museum for Central Africa, 2015.

Bastin, Marie Louise. “Ritual masks of the Chokwe.” African Arts 17 (4, 1984): 40-45; 92-93; 95-96.

Boone, Sylvia Ardyn. Radiance from the waters: ideals of feminine beauty in Mende art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

Bourgeois, Arthur P. Art of the Yaka and Suku. Meudon, France: A. et F. Chaffin, 1984.

Bourgeois, Arthur P. “Yaka masks and sexual imagery.” African Arts 15 (2, 1982): 47-50; 87.

Carlson, Amanda. “Masquerading by women: Ejagham.” In Philip Peek, ed. African folklore: an encyclopedia, pp. 244-246. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Falola, Toyin, ed. Victor Ekpuk: connecting lines across space and time. Austin: Pan-African University Press, 2018.

Gottschalk, Burkhard. Bundu: Bush-devils in the land of the Mende. Düsseldorf: U. Gottschalk, 1992.

Grootaers, Jan-Lodewijk and Alexander Bortolot, eds. Visions from the forests: the art of Liberia and Sierra Leone. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2014.

Herreman, Frank and Constantijn Petridis. Face of the spirits: masks from the Zaïre Basin. Ghent: Snoeck-Ducaju, 1993.

Jordán, Manuel, ed. Chokwe!: art and initiation among the Chokwe and related peoples. Munich/New York: Prestel, 1998.

McClusky, Pamela. Art from Africa: long steps never broke a back. Seattle: Seattle Art Museum in association with Lund Humphries, 2002.

Nicklin, Keith. “Nigerian Skin-Covered Masks.” African Arts 7 (3, 1974): 8-15; 67-68; 92.

Nicklin, Keith. “Quest for the Cross River skin-covered mask: methodology, reality and reflection.” In Karel Arnaut, ed. Re-visions: new perspectives on the African collections of the Horniman Museum, pp. 189-207. London: Horniman Museum and Gardens/Coimbra: Museu Antropólogico da Universidade de Coimbra, 2000.

Nicklin, Keith and Jill Salmons. “Cross River Art Styles.” African Arts 18 (1, 1984): 28-43; 93-94.

Phillips, Ruth B. Representing woman: Sande Masquerades of the Mende of Sierra Leone. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1995.

Röschenthaler, Ute. “Honoring Ejagham Women.” African Arts 31 (2, 1998): 38-49; 92-93.

Siegmann, William and Judith Perani. “Men’s masquerades of Sierra Leone and Liberia.” African Arts 9 (3, 1976): 42-47, 92.

Siegmann, William and Cynthia E. Schmidt. Rock of the ancestors: nama k ni: Liberian art and material culture from the collections of the Africana Museum, Cuttington University College, Suakoko, Liberia. Suacoco, Liberia: Cuttington University College, 1977.

Talbot, D. Amaury. Woman’s mysteries of a primitive people: the Ibibios of Southern Nigeria. London, Cassell, 1915.

Talbot, Percy Amaury. In the shadow of the bush. London: William Heinemann, 1912.

Other Aspects of Youth

While traditional art may include babies or backed toddlers to indicate motherhood, represent

mourned infants or show marriageable youths as evidence of an ideal, children depicted on their own are exceedingly rare. Some contemporary artists, however, feature them as elements in a crowd or as the main subjects, whether as ordinary youngsters or in special roles, such as child soldiers. At times they bear the weight of metaphor, as in some of Yinka Shonibare’s art (Fig. 328). His Champagne Kids installation featured a party of revelers, many clutching champagne bottles with globes as heads, who frolic while they precipitate a global financial crisis without a care in the world.

Peju Alatise is no less metaphorical in her work “Flying Girls,” an installation that formed part of Nigeria’s first pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale (Fig. 329). Here, however, the metaphor is less global in impetus, though sadly just as universal in application. The life-size group of eight naturalistically rendered winged girls, surrounded by a swirl of birds, stand in a second swirl of leaves. Based on a novel Alatise wrote, it speaks to the plight of housegirls. Such children work as childminders and maids, either in the homes of wealthier relatives for the price of their feeding, or brought by brokers to strangers’ homes, their meager salaries sent to their parents with the broker collecting their own fees. Subject to long hours, beatings, and sexual assault, their hard lives lead to dreams of a life of freedom and possibilities where they can soar above their drudgery and abuse, joining the birds who may only be other winged teachers or stand in for powerful women who straddle the boundary between this world and the supernatural realm.

Many of Alatise’s works explore the multiple difficulties that face young girls whose lives are circumscribed by family, culture, and religion. Social roles that compel marriage and motherhood as the only acceptable female destiny are referred to in High Horses (Fig. 330), the girls’ hidden faces speaking to their sublimation of personal dreams and expression. Orange Scarf Goes to Heaven (Fig. 331) speaks to Alatise’s own experience as a 16-year-old. As they arrived at the Musli prayer ground, the bright headscarf she wore barred her from entry, and she was informed that drawing attention to oneself through attractive clothing and accessories was a punishable offense for females, both in this world and the afterlife. In the triptych, Orange Scarf is the cynosure of her peers’ attention, their body language conveying their surprise, aversion, and condemnation–not only because she has avoided the “purity” of their white attire, but because she dares to be a non-conformist. In this work, Alatise demonstrates that female independence and self-determination must battle not only males, but other females. Her Orange Scarf’s rejection of the norm may have been without premeditation, but her heterodoxy sets her in opposition to those girls in other African cultures who participate in initiation.