Chapter 3: Themes in African Art

Chapter 3.5 Art and Medicine

“Medicine” means multiple things in Africa. There are Western medicines, administered through injections and pills, meant to cure diseases and manage chronic conditions. There are African medicines that do the same thing–decoctions from roots and leaves meant to treat yellow fever, poultices from leaves that draw out materials from wounds, and other treatments that involve efficacious herbs and other substances. That, however, is only one type of medicine. Medicine is the English term also used for substances, made to recipes, that use supernatural powers to effect change–not necessarily changes that involve health. There are innumerable types of medicine, each created to a specific formula and activated through incantations, usually by a ritual specialist: medicines for love, exam success, disposing of an enemy, making someone impervious to bullets, becoming invisible to your lover’s spouse, becoming pregnant, preventing a specific disease, becoming a witch, fighting witchcraft, punishing errant wives, and countless others. While there are specifically Christian and Muslim medicines (covered later in this book), traditional medicines are usually made from natural substances and include botanical matter, crystals, metal, particular animal skins, claws, teeth, quills, horns–aggressive and protective parts–and objects whose names are homonyms for a desired result.

Medicines can be used in a variety of ways. One can bathe in an herbal preparation, for example, then go to sleep without rinsing or drying. One can drink a preparation, or wear a garment or ring that has been literally cooked in a boiling decoction. The skin can be cut and a powder rubbed in, or, in the case of one Edo medicine from Nigeria, it can be rubbed with leopard fur to make those encountered respond with respect and fear. It can be ground finely and blown at a rival, heated to produce invisible barriers, or placed over a door to “tie up” prospective thieves. Most commonly, it can be encased in a leather packet as an amulet and worn, either under the clothing, around the neck, or attached to clothing (Fig. 332) or headgear. Medicines can become polluted by certain practices or encounters, but can usually be “woken up” by certain prayers and other preparations. While none of these medicines necessarily constitutes an art form, art objects can encase medicines or depict them (Fig. 333), as well as represent the medicine owned by an individual or group, such as the Poro or Sande societies’ description of their masquerades as the physical manifestation of their hale, or medicine.

Bamana Art and Medicine: the Komo mask

This Bamana Komo headpiece (Fig. 334) is vastly different from the smooth, polished, graceful forms of Bamana chi wara antelope crests. Its surface is crusty and irregular, its cracks revealing nothing of the wood underneath. Although animal-like, it cannot be identified with any particular creature. While the antelope horns, wild boar tusks, and porcupine quills suggest land associations, the performer’s costume is made from hand-woven cloth covered with (depending on the region) vulture, chicken, hornbill and/or guinea fowl feathers (Fig. 335), the whole spread over a cylindrical reed framework that disguises the body. This inclusion of the realm of the air makes the identity of the “animal” represented even more ambiguous, and some headpieces include additional bundles of feathers. Its open maw threatens to devour observers, yet no eyes are visible. Its multiple textures are one of its chief characteristics, yet they do not invite touch. These masks are empowered by the sacrifices that have obscured the headpiece’s original wooden structure, and by the medicines that provide its textures. Their forms are fairly consistent (Fig. 336), differing mostly in the presence or absence of ears and teeth, as well as the number and type of attached medicines. The works fit on the upper part of a wearer’s head, much like a hat. It remains unclear whether the feathered costume covered the face or not. The face remained visible in the few photos of Komo performances that exist, but most of these were staged; there are reports that both headpiece and costume were periodically raised on a pole during the dance.

The process of carving requires ritual sexual abstinence on the part of the artist as an essential preparation for work, as well as communion with a nature spirit they have a personal relationship with. The initial wooden carving has somewhat stubby horns, as these are only meant to act as supports for the attachment of real horns. Repeated sacrifices add nyama, the power in all living (and some inanimate) things, that empowers the mask. The blacksmiths must obtain the horns, tusks, quills, and other medicinal defensive/aggressive animal parts to add to the wooden core; these animals’ deaths release nyama, a powerful, unpredictable force that blacksmiths can control and direct. Medical imaging of certain Komo headpieces has revealed that the horns can even have additional medicines inserted before attachment–both visible and hidden dangerous forces are in operation. Porcupine quills are associated both with protecting wisdom and with piercing weapons such as arrows. Birds, the source of feathers, considered communicative partners in divination and be capable intermediaries between prepared individuals and spiritual knowledge. The extended maw may depict an exaggerated hyena’s jaws, dually alluding to hyenas’ perceived ability to consume sorcerors and the senior Komo members’ ability to transform into hyenas to this end.

The blacksmiths who make and use these headpieces play important roles in Bamana society, although non-blacksmiths sometimes prefer to keep a social distance from them. Like other Mande peoples, the Bamana are a caste society, with farmers forming the landed aristocracy and other occupational groups (nyamakalaw) having distinctive social positions. Blacksmiths, whose wives are potters, are not only metal workers, but also wood sculptors. Besides these artistic roles they are medical experts, diviners, circumcisors, and ritual specialists who produce and administer medicines, and for that reason, they are considered both powerful and potentially threatening. Having consumed and bathed in medicine most of their lives, they literally embody medicine.

Since the mid-20th century, Islam has had a profound effect on many of the various Bamana men’s societies and their associated arts (see chi wara in Chapter 3.1). Nonetheless, the blacksmith-led men’s society known as Komo is still active today. Its purpose is to protect members and society as a whole, and one of its chief goals is to detect and destroy malevolent sorcerors, including rival Komo who might test a performer’s own supernatural abilities during the dance. The Bamana are not the only makers and users of Komo–the Tagwa Senufo of western Burkina Faso obtained the right to Komo, still performing songs in the Bamana language, so the source of any given headpiece is ambiguous without collection data.

The Komo members who wear masks do so only in the presence of men who have paid for the simplest Komo initiation level, the one that allows viewing of a performance. The masquerade is anathema to all but a few special women; other women must not view it, although they may hear the sounds and songs of the performance (see video above). Divination takes place when the masquerader is dancing; he answers members’ questions through songs in an instrument-distorted voice, which are then interpreted by an associate.

When not in use, the mask is kept in a dedicated Komo structure, and it will usually be buried there after its owner’s death. Some, however, are hidden before that point, the owner’s expectation being that a relative or other Komo member may advance to a state that will make them capable of using the mask. Its location will then be revealed in a dream. The Komo structure holds other power objects, including the portable altars known as boli (Fig. 337). Like the Komo masks, boli have encrusted surfaces, built from layers of sacrificial blood, food, herbs, kola chewings, honey, and

alcoholic drinks. While their core may be wooden, medical imaging has revealed that some include cloth, nails, bones, and vegetable matter. They serve as portable altars, and high-ranking members can direct their concentrated nyama towards a situation or an individual. Their vague form–here somewhat bovine, sometimes hippo-like or anthropomorphic–recalls the ambiguous, mysterious identity of the masks. Their very lack of clarity suggests the secrecy in which they, as well as Komo’s activities in general, are held.

alcoholic drinks. While their core may be wooden, medical imaging has revealed that some include cloth, nails, bones, and vegetable matter. They serve as portable altars, and high-ranking members can direct their concentrated nyama towards a situation or an individual. Their vague form–here somewhat bovine, sometimes hippo-like or anthropomorphic–recalls the ambiguous, mysterious identity of the masks. Their very lack of clarity suggests the secrecy in which they, as well as Komo’s activities in general, are held.

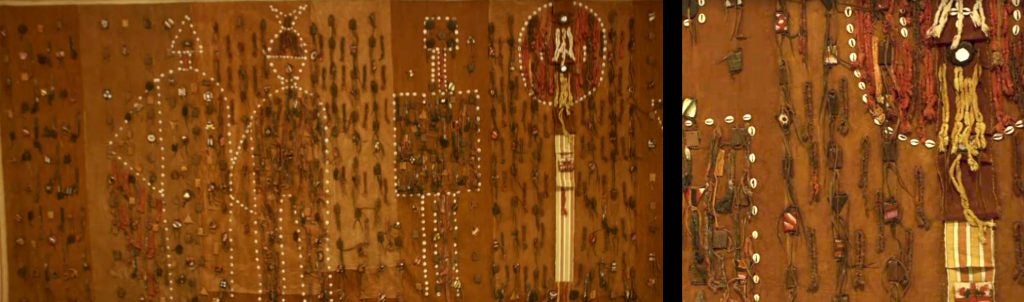

In their role as ritual specialists, blacksmiths make medicines for themselves and others. Some of the most visible Bamana medicines are in the form of leather covered amulets that are sewn to the tunics of hunters. Male hunting associations can include members of any caste, so farmers and blacksmiths can each be hunters. They still rid the region of threatening animals, but they are prepared before facing the natural and spiritual danger to be found in the bush, a place of nyama; in the past hunters were also warriors, since they were trained to use guns and other weapons, move stealthily, be observant, and be medicinally prepared. Their distinctive amulet-laden garments were worn primarily at gatherings of their society, when hunters’ bards would sing the praises and biographies of great hunters, living and dead. The tunics are laden with a variety of visible and invisible medicines, many in leather-wrapped duiker antelope horns. The underlying garment can be plain cotton that began as white, but was washed in a mordant; the color is associated with blood (Fig. 338). The rawhide strands that hang on the surface are also medicine. They have been soaked in the saliva of healers, their words carrying nyama. Other tunics begin as bogolonfini, or mudcloth–cotton that was woven by men, then pattern-dyed by women (Fig. 339).

Abdoulaye Konate (born 1953), an academically-trained artist from the Bamana region, used hunters’ shirts and their talismans as inspiration for his huge Homage to Mande Hunters wall hanging (Fig. 340), an early creation. It magnifies the standard tunic until it takes up a whole wall. Its brown color echoes that of the “cooked” in medicine, and its surface picks out abstract forms in cowrie shells, the whole covered with spaced amulets and rawhide strands. Konate, educated first at the Institut National des Arts de Bamako, and later at Havana’s Instituto Superior de Arte, works predominantly in cloth, his creations sometimes covering a whole floor. Many of his works from the 1990s and 2000s included amulets (gris-gris in his French titles), as this video of one of his exhibitions shows.

Additional Readings

Brett-Smith, Sarah C. The Making of Bamana Sculpture: Creativity and Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Diamitani, Boureima Tiékoroni. “Observing Komo among Tagwa People in Burkina Faso: A Burkinabe Art Historian’s Views.” African Arts 42 (3, 2008): 14-25.

Gagliardi, Susan Elizabeth. Senufo Unbound: Dynamics of Art and Identity in West Africa. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art/5 Continents Editions, 2015.

Konkouris, Theodore. “Recalling the Past in Song: Mande Hunters’ Musical Ceremonies.” In Fiona Larkan and Fiona Murphy, eds. Memory and Recovery in Times of Crisis, Ch. 7. New York: Routledge, 2018.

McNaughton, Patrick R. “Bamana Blacksmiths.” African Arts 12 (2, 1979): 65-66; 68-71; 92.

McNaughton, Patrick R. The Mande Blacksmiths: Knowledge, Power, and Art in West Africa. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1993.

McNaughton, Patrick. “The Shirts Mande Hunters Wear.” African Arts 15 (3, 1982): 54-58; 91.

Nkisi of the Kongo Peoples

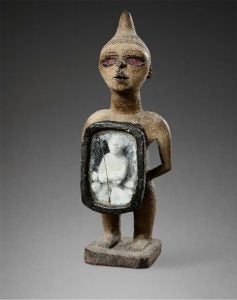

Belief in the powers of the dead, as well as in the powers of the living to exercise some control over them, have led to the production of many impactful Kongo sculptures. Their appearance demonstrates collaboration between sculptors, ritual specialists (here called nganga), and clients. Many Kongo medicines (nkisi) are non-figurative, composed of ingredients connected together, or hidden within cloth bundles, bottles, or pots (Fig. 341). Figurative nkisi often incorporate these same types of ingredients or are hung with them; they address similar goals.

These power figures (Fig. 342) or nkisi most commonly take the form of male or female figures, as well as single or Janus-headed dogs; occasional simians also exist. When the sculptor created a figurative nkisi, he carved a cavity in its torso, with additional cavities sometimes placed on the head, elbow or back, and medicine packets or attachments connected to it on the surface level. The nganga, after determining the work’s specific purpose, would gather the appropriate ingredients to lure the spirit of a dead person to take up residence in the sculpture and carry out the appropriate tasks.

These ingredients varied according to function, but one consistent inclusion was earth from a powerful person’s grave or another gathering place of spirits of the dead, such as a stream bottom. These substances lured the spirit and made it feel at home. Such spirits were not ancestors with family connections to the makers or users of the nkisi, but those who were effective in life and could use their abilities to new ends.

Other ingredients included objects whose names were puns associated with characteristics that reinforced the nkisi‘s capability and metaphors for desired qualities or actions. Once the substances were inserted, they were sealed from view with resin and, usually, a mirror. The mirror was synonymous with water, for the dead were housed in a world under the water. The nganga could use the mirror as a divination device, peering into the spiritual world to discover the causes and cures for specific situations.

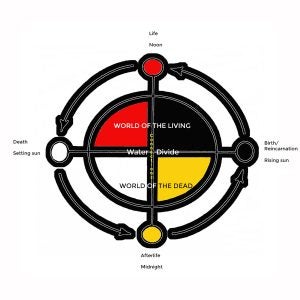

Kongo philosophy posits a spiraling trajectory of life that is graphically represented as a cosmogram (Fig. 343). In it, this world and the spiritual world are divided by a horizontal line that represents a permeable barrier of water, while a vertical line marks the interconnectivity of the living and the dead through individuals such as the nganga and beings such as those inhabiting nkisi. The cosmogram appears on burial mats, marked the ground for oathtaking, White, the color particularly associated with the dead, and red, the color of violence, transition, and the power of the prime of life, often mark nkisi faces or the edges of their mirrors.

Like most Kongo figurative art, nkisi are fairly naturalistic (some examples extremely so), although their head-to-body proportions are unnatural, often set at 1:3 or 1:4. Although they can look somewhat ominous, particularly when their medicinal attachments remain, They assumed different poses, accoutrements, and accessories because their purposes differed. While some were healers, devoted to curing specific maladies, others hunted down thieves and miscreants or inflicted disease on enemies.

Numerous works share traits that provide partial symbolic meanings and clues to their functions. The medicine pack of a female nkisi in the Wereldmuseum Rotterdam lacks silvering and allows observation of its ingredients (Fig. 344). Chief among them is a miniature figure of a mother with child, painted white with kaolin, as well as white spiraling shells and stones. These elements suggest the nkisi was dedicated to conception, for the fetus is compared to a snail in its shell. This work is considered to be associated with “the below,” the world of water, coolness, the color white, healing, and afflictions of the lower body.

Another nkisi in Liverpool’s World Museum suffered some damage to a medicine pack on the head that revealed its contents; the figure’s torso cavity was also x-rayed. Ingredients attached to the head included magnetite crystals, a small snake, charcoal, and a bird of prey’s egg; the torso pack also seemed to include crystals. Information supplied by the collector suggests this nkisi‘s resident spirit was associated with “the above” and violence. Some of its medicinal ingredients alluding to aggressive animals who attack with great swiftness. Named “Chcôca”–those nkisi with known abilities were known by personal names–its attacks were said to cause swelling, sores, and rheumatism.

Many examples include or once included feathered headdresses. These indicate associations with “the above”, the realm of both raptors and violent lightning strikes, suggesting an nkisi inhabitant capable of swooping down on victims and exercising retribution. A number of power objects show the figure chewing on a root. This is an action that appears on numerous depictions of monarchs (Fig. 345), and indicates a form of impartial justice aided by the munkwiza (Costus lucanusianus) root or vine that could detect witches and defy death. It was an insignia of rule, indicating continuous growth and revival, and was included as an ingredient in the ruler’s nkisi of investiture. When he pointed it at someone, they would swell up and die, so this nkisi‘s use munkwiza is likely linked to his powers to harm and the ability to identify witchcraft. Some nkisi have bamboo attachments–the gunpowder-stuffed “night guns” of Fig. 341 above–that similarly attack witches and sorcerers. Hunting nets are components of still other nkisi. On one level, they suggest the binding of unseen forces, but they also indicate a spirit who can track down individuals and visit them with retribution.

.

Some of the most visually striking power figures are known as nkisi nkondi, or hunting nkisi (Figs. 346, 347, 348). These can bristle with nails, each indicating a contract with a client seeking to punish someone who has committed a crime, broken an oath, or otherwise offended. The insertion of iron is meant to awaken the in-dwelling spirit to track the offender and inflict pain, disease, or death, unless restitution is made. The varied textures and altered silhouettes of these figures attest to the role of clients’ in the figures’ appearance: they no longer look as they did when they left the artists’ hands or even the nganga‘s hands, but demonstrate the results of many transactions.

Male nkisi were often paired with female nkisi, or with dog representations, since the latter are said to live in a village at the border of this world and that of the spirits, their hunting skills particularly suited to tracking the guilty (Fig. 349). A better understanding of any specific nkisi requires its case history and knowledge of its medicines; fortunately, some were collected with this information, although the vast majority were not (see hotspot images below for individual biographies). Those whose powers were particularly potent were known by their personal names

Small nkisi might be owned by individuals, such as warriors who traveled with them for their divinatory abilities. Others were owned by nganga, or by communities, those considered particularly efficacious drawing pilgrims from hundreds of miles away who were eager for their cures or punishing abilities. Wary about the power the Kongo invested in nkisi, the Portuguese began seizing them in their territories in the last decade of the 19th century, while the Belgian and French officials (as well as missionaries, both European and Kongo) similarly stripped Kongo nkisi from their shrines. Although this pattern was not new–both written and visual allusions to the destruction of Kongo “idols” occurred in the 16th through 18th centuries, conducted by both Christian Kongo kings and foreign missionaries–the depredations during the colonial period have now reduced medicine to non-figurative forms.

Additional Readings

Bassani, Ezio. “Kongo Nail Fetishes from the Chiloango River Area.” African Arts 10 (3, 1977): 36-40; 88.

Fu-Kiau, Kimbwandènde Kia Bunseki. African cosmology of the Bântu-Kôngo [1980]. Brooklyn, N.Y. : Athelia Henrietta Press, 2001.

LaGamma, Alisa, ed. Kongo: Power and Majesty. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.

MacGaffey, Wyatt. Art and Healing of the BaKongo Commented by Themselves. Stockholm: Folkens Museum/Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991.

MacGaffey, Wyatt. “The Eyes of Understanding Kongo Minkisi.” In Astonishment & Power: Kongo Minkisi and the Art of Renée Stout., pp. 20-103. Washington, DC: Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, 1993.

MacGaffey, Wyatt. “Franchising minkisi in Loango: Questions of Form and Function.” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics nos. 65/66 (2014/2015): 148-57.

MacGaffey, Wyatt. Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2000.

Thompson, Robert Farris and Joseph Cornet. The Four Moments of the Sun. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1981.