Chapter 3: Themes in African Art

Chapter 3.6: Art and Divination

People throughout the globe try to make sense of their world through a variety of methods meant to tap into an unseen sphere, whether through the Chinese I Ching, European tarot cards or Inca spider divination. African divination frequently has the same recourse: using a random method to tap into the order of the spiritual world in order to determine problems’ causes and cures. Specialist diviners are apprenticed, trained and then become masters. Their clients are often from areas some distance away, for local diviners might employ intelligence relating to the client’s family or work situation, while a stranger is truly dependent on their methods of accessing the spirit world. Many different divination methods exist; some African peoples themselves have multiple methods. Not all, however, employ art objects. Dogon diviners from Mali, for example, draw boxed diagrams into the sandy soil, arranging sticks, symbols, depressions, and food within its cells (Fig. 350). They activate their process through words, calling upon a fox to manifest answers to clients’ questions. When the fox comes to feed, he disarranges elements in the diagram, and the diviner reads these traces to interpret the problem at hand.

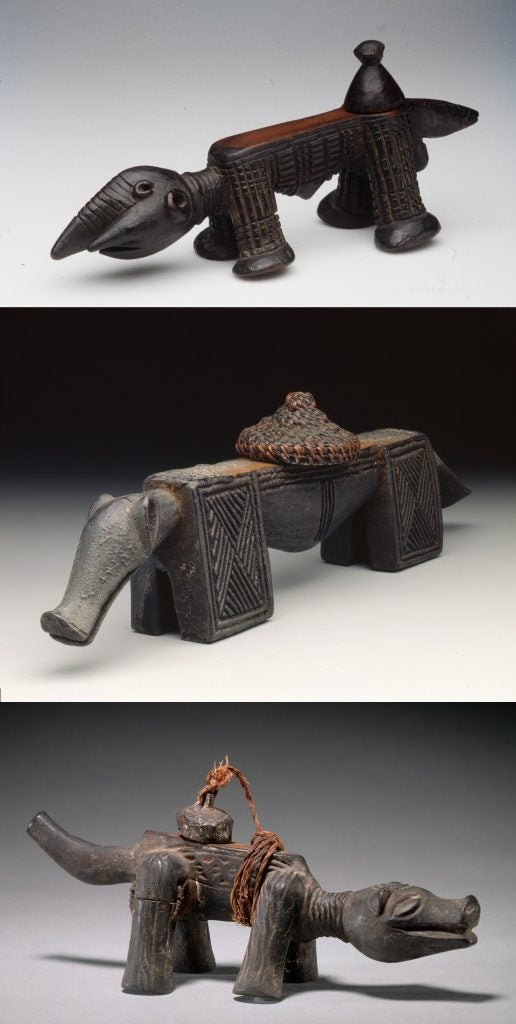

Some African divination methods use objects to access the other world. Diviners among the Kuba of the Democratic Republic of Congo employ friction oracles (itombwa) that artists carve in the shape of animals, often dogs , but also crocodiles, wild pigs, and elephants (Fig. 351); rarely a human figure (often placed horizontally and mounted on four animal legs) forms the instrument. Diviners use them to commune with nature spirits to diagnose illnesses’ causes and cures, catch malefactors, or isolate other issues troubling the community. Although wild animals are associated with the bush, and thus with the realm of nature

spirits, the common appearance of the domesticated dog relates to his hunting abilities, in this case through supernatural means. When a session begins, the diviner applies oil or water to the animal’s smooth back, then rubs the back with a utensil while asking a series of questions, Because of the moisture, the utensil moves smoothly; when the diviner chances on the appropriate issue, however, it will stop abruptly, a revelation from the other world. Extensive use creates a depression and a patina resulting from the oil and red pigment. Geometric patterns, which commonly decorate Kuba boxes, cups, pipes, and non-figurative objects, frequently ornament the animal’s body. The animal is usually abstracted. Although its legs usually lack definition, the position of head and tail convey a sense of alertness. Many of the Kuba’s immediate neighbors use similar divination forms, and other types of friction oracles are known further east in Central Africa.

Chokwe diviners from Angola, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo employ baskets or other containers filled with small objects when they perform divination (ngombo ya cisuka). Some of the objects are natural–twigs, claws, teeth, stones, seeds–but others are carved in the form of human beings, masqueraders, or are manufactured articles (Fig. 352). Together they constitute a miniature replica of human social life through symbolism and allusion. The diviner tosses the basket and reads the resulting configurations. Although objects have independent meaning, the ways in which they touch, overlap, or otherwise interact are essential to his interpretation. The diviner calls upon a specific ancestor to aid him in his endeavors, invoking him by shaking a rattle, as the video below shows. In the course of the divination, additional ancestral and nature spirits may intervene.

Senufo Divination in Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso

The Senufo have several different forms of divination. The most common type, however, may be that practiced by female specialists. Known as sandobele, they are a sub-set of the Sandogo women’s society. Each matrilineage designates one or two members to become diviners, but others can be driven to take up that occupation because they have annoyed a nature spirit who then makes them fall ill. This sends them

to a diviner who advises the client to form a working partnership with the nature spirit by learning to be a diviner herself. Occasionally men become diviners through this same route. Nature spirits (madebele) live in an invisible society similar to that of human beings, inhabiting the bush outside towns and farms. This can bring them into conflict with humans, but they can also form alliances with individual sandobele, and mediate between them and the other world to detect the causes of problems and return the latter’s clients’ to equilibrium. Many of the problems result from unsanctioned sexual contact of members of the matrilineage, which can lead to ancestral annoyance. Managing the human and spiritual consequences of these kinds of fractious transactions requires standby family specialists from Sandogo. Working with madebele in challenging. They are capricious, quick to anger, swift to punish, but trained sandobele know how to mollify them via proper care and respect, and persuade them to assist in a kind of friendly partnership.

Sandobele work with their clients in a specialized small office; these may be part of their own home or erected next to the house where twins were born. Male-female twins are valued by the Senufo and appear as the mythological children of the progenitors of the human race. More importantly, Senufo diviners seek to work through them because, since they share a womb, they are considered the conduits of perfect communication that does not require speech; likewise, twins can communicate with spirits. Diviners rely upon both the spirits of deceased twins in their own families and those of their clients to relay messages from the other world, and attempt to mirror both their client and relevant spirits as they work, thus becoming pseudo-twins themselves. They sit on the ground, legs stretched out, facing a similarly-posed client, and hold one of the client’s hands during the divination process. Their shifting twin-like behavior (cycling between reflections of the client and the spirit) creates an atmosphere of affinity and accord that smoothes communication and facilitates answers to the clients’ problems. During divination, sandobele wear brass rings and bracelets (Fig. 353), usually paired and often bearing images of pairs, adding to the twin theme.

Twinned images are a basic part of sandobele divination. All diviners work in the presence of a figural pair (tugubele), an example of which can be seen HERE. These represent idealized madebele twin spirits (for nature spirits are believed to actually have feet that face backward; some are hairy or have oversized heads or other odd features) that take up temporary residence in the figures as they interact with the diviner. A musical invocation–the madebele cannot resist music–lures the nature spirits to the divining site and puts them in a receptive state.

During the course of her session, she takes out a group of small, jewelry-like brass objects, as well as various objects such as cowrie shells, nail polish containers, pens, and dried kola nuts. She casts these from a container, then interprets their fall with the guidance of spirits. Although many of the tiny brass elements are figurative, one of the key inclusions is a miniature bracelet decorated with a python, the messenger of spirits–an object frequently worn in multiples by a diviner, herself a messenger, or by those Senufo troubled by nature spirits.

The nature spirits are attracted by beauty–music and aesthetic objects pull them magnetically. Diviners upgrade their objects as they become more successful, and twinned figures are among commonly depicted objects. Though small, they are carefully modeled, their appearance seen in the diviner’s dream and communicated to a brasscaster who uses the lost wax casting technique. This pair (Fig. 354) has the long torsos of the much larger Senufo wooden sculptures used by the men’s Poro Society (though it shares a name with the men’s society of the Poro/Sande complex in Sierra Leone/Guinea/Liberia, it is a completely separate entity). In an effort to attract more spirits and ensure their cooperation, sandobele also commission decorative wooden carvings that play no role in divination, but simply upgrade the work environment for all concerned. Frequently these status sculptures are equestrian images (Fig. 355) that both attest to the diviner’s reputation and skill and speak as references to power. This example stresses more rounded forms than many Senufo carvings, but its rider clearly dominates the horse through hieratic scale; his steed merely reflects his own elevated position and is said to represent the bush spirits’ mobility as they move from their invisible homes to the diviner’s human world.

Once divination provides a diagnosis of the source of a client’s problems, a cure is presented. This commonly takes the form of a prescription that is worn: a painted cloth garment, brass amulets tied at a child’s ankle or waist (Fig. 356), or brass jewelry–particularly rings (Fig. 357) or bracelets–worn by adults. Through their attractiveness, these appease irritated bush spirits, and are meant to ensure the client and spirit troubling her remain on amicable terms.

Additional Readings

Gagliardi, Susan. Senufo Unbound. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2015.

Glaze, Anita J. “Senufo Ornament and Decorative Arts.” African Arts 12 (1., 1978): 63-71;107-108.

Glaze, Anita J. “Woman Power and Art in a Senufo Village.” African Arts 8 (3, 1975): 24-29; 64-68; 9.0.

LaGamma, Alisa and John Pemberton III. Art and Oracle: African Art and Rituals of Divination. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

Peek, Philip M. “Couples or Doubles? Representations of Twins in the Arts of Africa.” African Arts 41 (1, 2008): 14-23.

Suthers, Ellen. “Perception, Knowledge, and Divination in Djimini Society, Ivory Coast.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, 1987.

Ifa Divination Arts among the Yoruba of Nigeria and Benin Republic

The Yoruba have many different divination practices, but value Ifa divination as their most complex and accurate practice. This form of divination is mathematically-related, relying on an extensive body of oral poems and narratives. These correspond to a numerical combination the diviner produces either by using a divination chain (opele) with eight “seeds”–these may be actual seedpods or cast brass or ivory pieces (Fig. 358)–or by using a more complex set of equipment that employs numerous art objects. The latter method allows the diviner to display more costly equipment that underscores his success and is upgraded as recognition of his skills becomes widespread. With the opele method, the diviner casts his chain numerous times, noting whether the positions of its eight markers are “open” or “closed”. In the second method (Fig. 359 and video below), the diviner passes 16 palm nuts from one hand to the other, noting whether he is left with an odd or even number of nuts in his hand, making corresponding binary marks in sawdust or sand on a carved wooden board in front of him. Both methods produce one of 256 possible configurations, which in turn allow them to recite an associated poem and draw upon related oral literature to interpret the throw. As such, both methods use randomness to access a cosmic order that will define the root cause of a client’s problem and offer a spiritual solution. The Yoruba, whose traditional religion includes both a High God (Oludumare) and uncountable lesser deities (orisha), associate Ifa divination with the orisha Orunmila (or Ifa), who epitomizes wisdom, purity, and moral order.

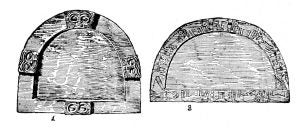

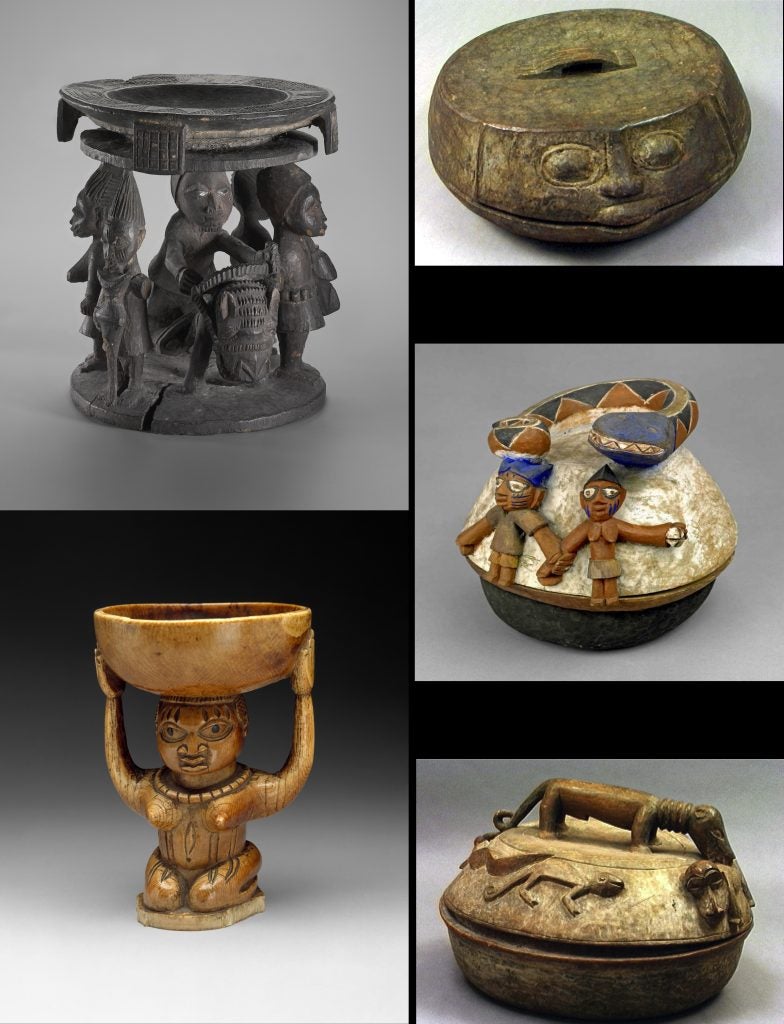

In the more complex Ifa divination method shown in Fig. 359, associated art objects include a wooden tray (opon Ifa) (Fig. 360) and a tapper (iroke Ifa), as well as a container to hold the sacred palm nuts (agere Ifa) and, usually, a free-standing representation of what appears to be a human head (Fig. 361). The trays are most commonly rectangular or circular, although there are lunette or half-circular versions as well (Fig. 362). The reverse side of the trays is plain, except for a centrally located carved depression that mimics the board’s shape–this allows the sound of tapping the board at the center to be magnified. For the Yoruba, the trays always have a raised border that typically includes at least one carved face as well as either geometric motifs, segmented sections with figural or animal representations, or a combination of the two. The face that appears on most boards may only be represented once (positioned across from the diviner), or can appear in multiples (usually multiples of four). It represents not Orunmila, but another orisha known as Eshu. Although the orisha are usually personified, Eshu is the only one who is typically represented in art. A friend to Orunmila, he represents chaos in opposition to Ifa’s order. With chaos, however, comes opportunity, and with divination and the sacrifices it prescribes is a chance to change outcomes. Eshu is considered the gatekeeper to the other world, guardian of the crossroads that mark the division of our world and the spiritual world, and the small head that many diviners own also represents him. Before any sacrifice or interaction with the other world, Eshu must be invoked.

The diviner (babalawo) begins his session by spreading the sawdust on the surface, marking a crossroads on it, and tapping the center with his iroke (Fig. 363). His invocations to Eshu and Orunmila are followed by references to other deities and to deified diviners of the past; some of the carvings on the trays’ borders are touched during the references to now-deceased diviners. Depending on the complexity of the tray, the carvings may be arranged symmetrically or asymmetrically.

A tray in the Musée du Quai Branly (Fig. 364) has a rare double border. The outer section is composed solely of abstracted birds shown in a birds’-eye view. Birds appear frequently in Yoruba art; as a liminal animal, they often portray those with powers to cross between the boundaries of our world and those of the spiritual world–these include diviners and other priests as well as the monarch and witches. They may be portraying how all people of power prostrate to Orunmila, or they could also (and simultaneously) refer to the birds that ultimately consume the sacrifices clients make in order to placate the spiritual or human causes of their problems.

The inner ring prominently features one representation of Eshu’s face, his oversized, bulging eyes conforming to general Yoruba style. The rest of the inner border is separated into discrete segments that function independently. The representation of a pipe-smoking profile figure with a long hairstyle is another reference to Eshu, who appears often sucking his thumb, smoking, or playing a flute, all phallic references that allude to his preoccupation with sex. He completely fills his mall section of the tray, as do the other motifs. There are numerous animal references: a mudfish (another liminal animal), a python devouring a four-legged, long-tailed animal of uncertain species (animals attacking or devouring one another are common tray sights, and may allude to human behavior); a crab, crocodile with mudfish, and a quadruped. An interlace motif completes the border.

Divination trays can vary significantly in their degree of decoration and the type of motifs they bear. Painted decoration is usually a feature of trays from the Benin Republic, although many of those remain unpainted as well. Eshu heads can range stylistically from the fairly naturalistic to considerable abstraction, and whether or not the head protrudes onto the board itself can be a regional indicator.

When diviners begin to use the trays, they may only be able to afford tappers (iroke Ifa) made from wood (Fig. 363, left). Nonetheless, this is carved in the shape of the tip of an elephant’s tusk, to imitate the upgraded ivory version. While some iroke only display small patterned bands at the base, while a few are conglomerations of multiple stacked figures. The overwhelming majority of tappers incorporate a nude kneeling woman. Sometimes her head is elongated so that it fills the implement’s tip (Fig. 363, middle), while at other times the plain tip appears to emerge from her head. In either case, its conical form mimics the supposed shape of the invisible inner head, the seat of destiny–a distortion that can frequently be seen in other Yoruba sculptures. The kneeling posture is one of reverence; Yoruba women greet in this position, and its supplication aspect can soften hard hearts, making it an effective position for begging favors from the orisha. Women’s nudity–here a reference to purity rather than with erotic overtones–is considered particularly efficacious for prayer and curses, a reference to the particular power women hold because of their life-giving abilities. The figure may embody humanity pleading the orisha for a “good head,” one that will guide them to a successful life; it simultaneously recalls women’s beauty and ability to please the deities, useful when one wishes to placate them and steer the course of events. Certain iroke position the figure in mid-implement, the tip being carved into the form of a somewhat abstracted bird (Fig. 363, right). Here the message references some women’s mystical “bird power” (ẹyẹ)–prophetic ability owned by witches who can transform themselves at night to accomplish both malevolent and benevolent deeds. Such women are considered to have power that equals that of the deities, and they may also have to be placated through sacrifice if found to cause a client’s problems.

Kneeling women also often beautify agere Ifa, often acting as caryatid figures for the containers that hold the sacred palm nuts (Fig. 365). These bowls are not always supported, and their decoration can encompass any feature of daily life, as well as references to animals with proverbial or symbolic associations (Fig. 366). Agere may portray weavers, birds, a copulating couple, or even the babalawo himself in the act of divination. As the most elevated of the babalawo‘s implements, an agere commands visual attention, and may be commissioned by the diviner himself or be a gift from a grateful client.

The equestrian is a popular agere caryatid figure. When he wears a shirt or tunic, he represents the northern Yoruba warriors of bygone days, and is a symbol of power, victory, and dominance. Bare-chested, he represents the diviner himself, willing to travel long distances in the pursuit of knowledge. He is the visual embodiment of one of the Ifa divination verses, in which Orunmila himself declares that diviners will ride horses.

A babalawo might also own a complex beaded necklace (Fig. 367), beaded attire to wear at a festival occasion (Fig. 368) and a beaded bag for equipment storage (Fig. 369). These items often favor asymmetry and considerable abstraction, traits not usually part of Yoruba sculptural arts. Those who have received royal recognition are more likely to own beaded accessories, since beaded attire (beyond a necklace or bracelet) are usually restricted to the monarch and those he favors. Yoruba rulers normally have a group of royal diviners who consult Orunmila regularly on their behalf.

Ifa divination systems and their close cognates can be found among many neighboring peoples, including the Nupe, Edo, Itsekiri, Isoko, Igbo, Igala, Fon, and Ewe. Most, however, employ the opele divination chain rather than art objects, or use a very simplified board with no or minimal decoration. The Fon of Benin Republic are an exception, but since many Fon objects seem to have been made by Yoruba artists, their pedigree is complicated (Figs. 370 and 371).

Additional Readings

Abiodun, Rowland. “Ifa art objects: an interpretation based on oral tradition.” In Wande Abimbola, ed. Yoruba Oral Tradition, 421-469. Ile-Ife, Nigeria: Dept. of African Languages and Literature, University of Ife, 1975.

Abiodun, Rowland. “Woman in Yoruba Religious Images.” African Languages and Cultures 2 (1, 1989): 1-18.

Abiodun, Rowland. Yoruba Art and Language. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Abiodun, Rowland, Henry J. Drewal and John Pemberton III, eds. The Yoruba artist: New theoretical perspectives on African art. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994.

Drewal, Henry J. “Art and Divination Among the Yoruba: Design and Myth.” Africana Journal 14 (2-3, 1987): 139-156.

LaGamma, Alisa. Art and Oracle: African Art and Rituals of Divination. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

Peek, Philip M., ed. African divination systems: ways of knowing. Bloomington: University Press, 1991.

Pogoson, O. I. and A. O. Akande. “Ifa Divination Trays from Isale-Oyo.” Cadernos des Estudos Africanos 21 (2011): 15-41.