Chapter 3: Themes in African Art

Chapter 3.7 Art and Death

Most traditional African religions do not believe death is the end of being. The deceased will typically be reincarnated into his or her own family as a member of the same gender experienced when living, or, if all goes well, will become an ancestor. But what does becoming an ancestor mean? Not everyone is eligible, for one has to be an adult with children. Those who die in infancy or as youths, those who die childless–none will become ancestors, for the entryway to ancestorhood is through the proper rites performed by one’s children at a funeral. Ancestors are tasked with ensuring their descendants behave according to long-established behavioral precepts. Breaking those regulations incurs ancestral wrath, which can be manifested individually through sickness, misfortune, infertility, or even death, or focused more broadly on a community through farm failures, droughts, or other disasters. Atonement through sacrifice can return life to equilibrium, and divination is usually the force that reveals the specifics of ancestors’ anger and the solution for their forgiveness. Blessings are sought from ancestors as well, and they are invoked and praised when good things happen within the family. In societies that have ancestral altars, these are usually the focus of interaction; otherwise, known gravesites attract sacrifice or alcoholic libations (palm wine, gin or schnapps) may more generally be made to the earth, the site of burials.

Coffins

Most burials (which should not be confused with funerals) were hasty in the past, because bodies rapidly decay in the heat. This initial step used to be a relatively basic affair, except for monarchs or extremely powerful individuals. Burials can still be fairly simple in many cases, with the body wrapped in a shroud or mat. In pre-15th century Jenne, however, corpses were arranged in a fetal position within giant pots; in some parts of Central Africa, they were bundled into giant baskets. After preparation, all were interred, accompanied by prayer.

For the most part, the use of coffins for burials was introduced by Christian missions, and they generally follow a Western format–a wooden box with metallic trim (Fig. 372). Some notable exceptions occur, however. Among the Ngata of northwestern Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as their Nkundu and Toba neighbors, important individuals once had large anthropomorphic coffins (Fig. 373). These occurred in both male and female forms, and were hollowed at the back. The space for the corpse is fairly narrow, but apparently the body was desiccated before being placed within, so these coffins began with skeletal remains. Their coloration of red and white recalling the passage from life to death in the art of the Kongo, members of a fellow Bantu-language group. The practice had ceased by the 1940s.

Early in the 20th century, a nearby ethnic group, the Mongo of the Democratic Republic of Congo, also constructed coffins for their great men, though these were not figurative (Fig. 374). The corpse was dried during the period it took for the coffin’s creation, then placed inside. This large wooden structure. said to have been made for a hunter, was patterned and ornamented with abstract allusions to animals, as well as sticks meant to represent spears.

In the Ga region of Ghana, in Accra’s suburbs, a new direction in coffin-making began in the mid-20th century. Seth Kane Kwei carved palanquins for chiefs; they were carried in them at festivals. In 1957, one client requested a palanquin in the shape of a cocoa pod–a whimsical departure from the standard cloth-covered wooden boxes. The palanquin was converted to a coffin when he died before taking possession of it, and Kane Kwei slowly turned his hand to other fancifully-shaped coffin models. By the time of his death in 1992, his products had become world-renowned, the subject of many photo essays and books. His former apprentice, Paa Joe, had established his own workshop, Kane Kwei’s shop continued under the leadership of two of his sons in succession, and about eight other workshops also took up the mantle. Their coffins often reflect the deceased’s profession (Fig. 375), either literally or metaphorically–a huge fish for a fisherman, a hen for a mother , an onion for a farmer, a soft drink or beer bottle for a woman who sells cold drinks. Their use is very limited–almost all Ghanaian clients are also Ga people, although a branch of Kane Kwei’s workshop is now on the main road just south of Kumase (Fig. 376). Certain Christian sects ban their use within their churches, although exceptions are made for coffins in the shape of a Bible. The coffins are borne aloft by pallbearers in procession, a focal point for lavish funerals, and then are buried. Since the 1970s, some Westerners have purchased coffins for themselves or for museum displays; growing interest after considerable international publicity in the 1990s has led to Internet sales, as well as to tabletop models that require less space for shipping and display. Prices are high, but are on a sliding scale; Ga buyers who actually will use their coffins are charged less. The introduction of this new form and its subsequent growth mirror earlier practices on the continent–an artist introduces a new form or a substantial variation of an established form, gains clients, and imitators emerge. Whether any given innovation will have a long lifespan with centuries of permutations is unknown at the time of its introduction; some new forms vanish within a generation.

Funerals

As occasions that can necessitate great expense, funerals do not always take place immediately after death. In the past, bodies might be buried quickly, but funerals could be delayed for months or years until the resources for the ceremony were gathered. With the advent of mortuaries, corpses can remain resident there until the family is prepared for public celebration. Funerals traditionally are held only for adults who have borne children; others are buried but not celebrated. For those who lived a full life and had many children, funerals can be a rollicking party, complete with musicians, dancing, food and drink, and, in some regions, masquerade involvement. The properly-conducted funerals that ensure ancestorhood also allow the deceased’s property to be distributed according to traditional law; otherwise it may be locked up, ensuring rites are carried out.

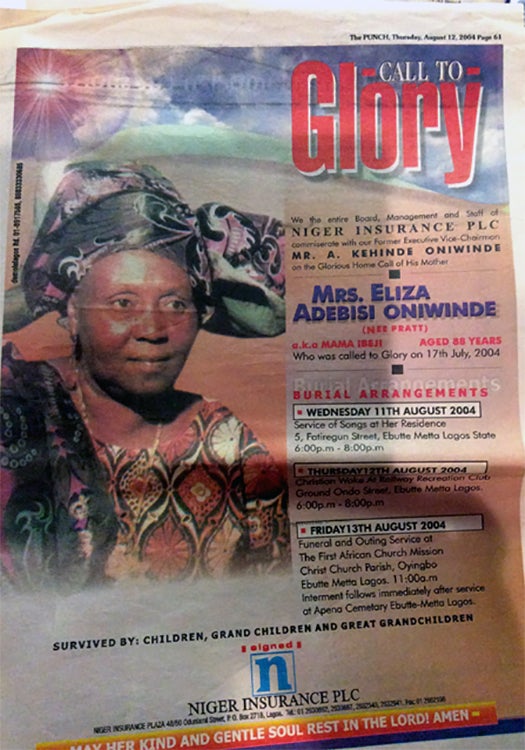

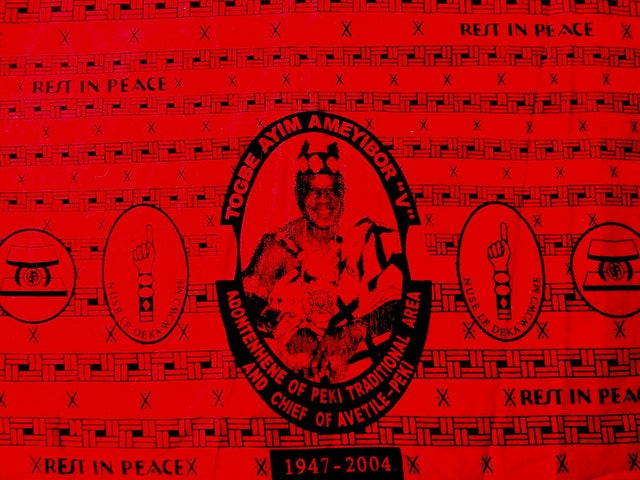

Obituary announcements can occasion great expense. These are made not only by the immediate family members, but by business associates of the deceased or their spouse and can occur in the newspapers (Fig. 377), as videos on television, or, as occurs in Ghana, on billboards (Fig. 378). These not only accord respect to the deceased and their families, but are meant to publicize the funeral so that attendance (even by strangers) will be high and satisfaction with the occasion will spread, enhancing the family’s reputation. Funerary celebrations can often last for several days, particularly if the deceased was a well-known individual.

Funerals can demand special attire. The Yoruba of Nigeria and Benin Republic, among other groups, often decide on a common cloth to be worn by family during a funeral (Fig. 379), or by those belonging to a social club in attendance. This is an example of aso ebi, a group cloth or uniform that can be styled to the wearer’s taste, a practice that extends to weddings as well. Among the Asante of Ghana, funerary cloths made from adinkra, a stamped textile, are worn in mourning colors of red, brown, and black (Fig. 380), women often wearing a headband as well. In some other regions, the family and friends of the deceased may commission a commemorative cloth with the deceased’s photo and birth and death dates (Fig. 381).

Cemeteries and Grave Sculptures

In many parts of Africa, burials take or took place in the home, with distinguished family members often interred in their bedroom. In some places, such as southern Ghanaian cities, public health regulations now outlaw this practice, and cemeteries have become common (Fig. 382), their contents ranging from simple graves to marble slabs with carving. The many British cemeteries along the coast influenced later sites, some of which were created by the British for their own citizens, others for the Ghanaian forces who fought in WWII and other European conflicts (Fig. 383).

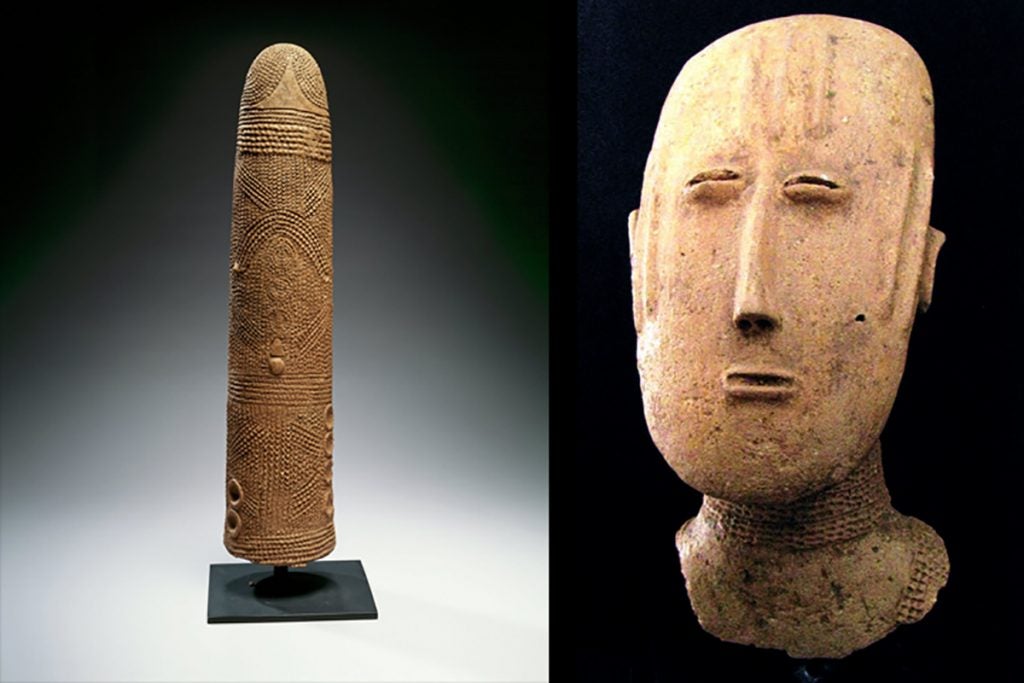

In other regions, cemeteries sited outside the community have long existed, fixing the dead away from the living to avoid unsanctioned interference. In southwestern Niger, near the Burkina Faso border, numerous cemeteries were created from the 3rd-11th century CE. The largest one found so far is the so-called Bura-Asinda-Sikka necropolis,

which contains over 600 decorated graves within a circular area only a little over a half mile in diameter. These were decorated with tubular or hemispherical terracotta vessels, their surfaces often richly patterned, which were surmounted by human heads or figures, including equestrian images (Fig. 384). The faces are abstract and flattened, taking either a rectangular or round form. The phallic vessels sometimes have navel-like protrusions. They were placed with their open side down, and included some grave goods. Excavations have yielded copper-alloy jewelry, beads, weapons, and pottery associated with the burials, the whole suggesting a society of considerable wealth, perhaps due to gold fields in the vicinity.

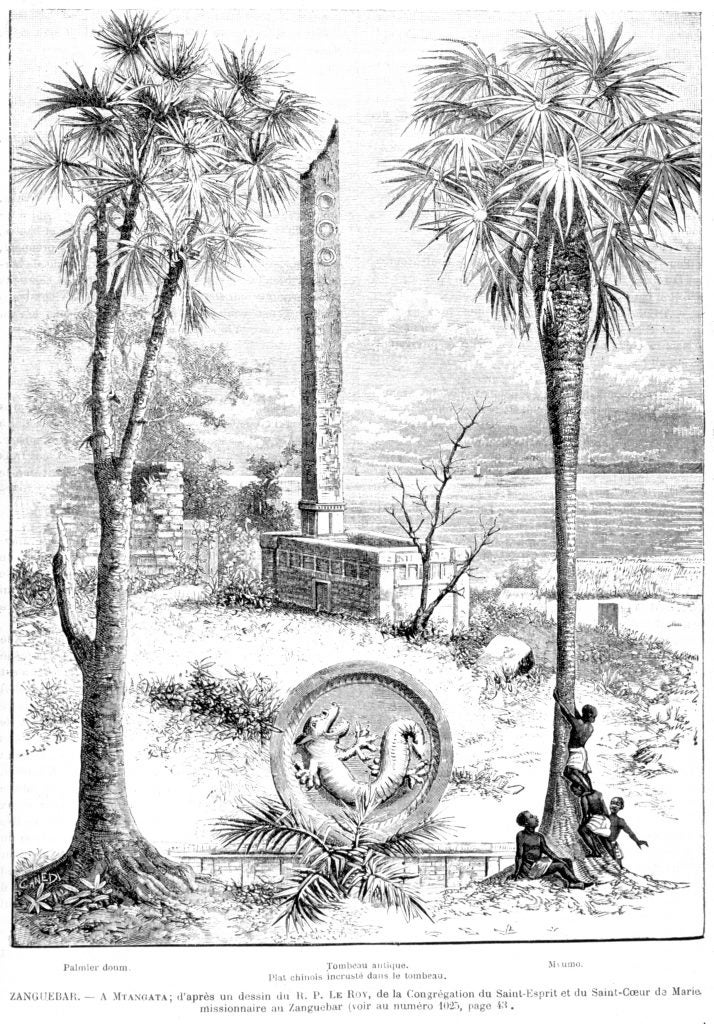

The Swahili of the East African coast have buried their dead in cemeteries for centuries, using rag coral to erect pillars (Fig. 385) or domed tombs for important traders. These were plastered over, the plaster often then carved in geometric patterns. From at least the 13th century, these often had imported porcelain from China or Vietnam pressed into the surface, decorative additions that often spoke to the wealth of the interred and put him in competition with his neighboring traders. In wealthy Swahili homes, similar porcelain was placed in niches, acting not only as exotica, but meant to absorb the malevolence of evil spirits.

A number of East African groups in Ethiopia and Kenya marked graves with both abstract and figurative structures. From the 2nd to the 4th century CE, stelae were erected over the burial places of important individuals as well as the rulers of Axum (also spelled Aksum) in present-day northern Ethiopia (Fig. 386). This state was a regional trading power from about the first century BCE to the 8th century CE, with marine trade featuring ivory that reached into Byzantium, other parts of the eastern Mediterranean, and across the Red Sea; in the 4th century CE, the ruler became a Christian and Christianity was established as the state religion. Although the stelae are often referred to as “obelisks,” they are not; Egyptian obelisks flanked temple entrances and were made in pairs, covered with hieroglyphics, and were topped by a pyramidal shape. Like the obelisks, however, the Axum stelae are monoliths, and have similar heights, ranging from only about three feet high to a soaring 97 feet–the taller ones marked royal tombs. While older examples exist, the large royal markers date from the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, and the carving on their surface replicates the exterior of elite stone buildings, such as

the palaces, including imitations of wooden beams, doors, and windows. Their tops are curved, with nail holes indicating former attachments. Tomb entrances are at the foot of the stelae (fig. 387), but the tombs themselves are empty, having been stripped of valuables long ago (Fig. 388). The use of stone for these tombs, like its use in Nubia to the north, speaks to a consciousness of history and a desire for permanence.

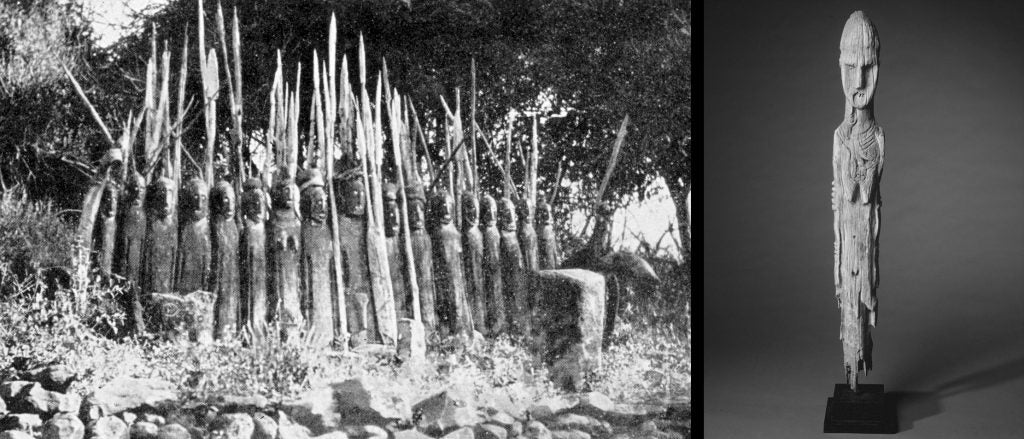

Stone is an uncommon building and sculptural material in most of sub-Saharan Africa. Some places further south in Ethiopia have short stone markers, but use wood for their main burial sculptures. The Konso of Ethiopia’s southwestern highlands live in high, rock-terraced communities surrounded by multiple rock walls. Their culture stresses male egalitarianism, but within their forests they have created burial sites for societal heroes. These are marked by narrow figures (wa’kka) (Fig. 389) of the commemorated individual surrounded by other carvings that represent their wives and the enemies they killed. Meant to be inspirational to their descendants, they are the pride of family members. The nude central figure (Fig. 390) depicts the hero,

who was ceremonially recognized as such when alive. He wears a carved forehead ornament that imitates a metal phallic form (kalacha) worn by heroes, priests, and notables of other nearby people (Fig. 391); these are said to have originated from the severed penises of enemies, stuffed and worn as more temporary trophies. Ostrich shells mark the eyes, while animal bones are used to create teeth. His masculinity is emphasized in multiple ways beyond the kallasha; his weapons are by his side, and statues of his wives flank him. Killed and castrated enemies are shown at the ends of the lined-up figures or in front of them, and an animal from one of the hero’s successful hunts lays before him, as do pebbles that mark fields he owned. The family’s respect is demonstrated by the wa’kka, but the town’s recognition is marked by a cylindrical stone placed in front of the wooden row, which will outlast them. At the time of their erection, the statues are painted red with black eyebrows, but weathering wears away most of the color over time. Protestant missionization, begun in 1954, has greatly impacted the creation of new wa’kka and other customs, despite the fact

that the graves do not conflict with Christian belief. The region, its landscape, generational transition stone stele markers, and the wa’kka themselves constitute one of the UNESCO World Heritage sites.

On the large island of Madagascar, numerous ethnic groups bury the dead in cemeteries that are marked with stone tombs or wooden sculptures. Some of the sculptures, such as figures by the Sihanaka (Fig. 392). are extremely large. The tombs of the sea-oriented Vezo on the western

part of the island, as well as those of the Sakalava who are the region’s larger population, are individually palisaded and kept away from settlements (Fig. 393). Figurative grave markers are also known among the inland Bara.

The Mahafaly, who live in the southwestern part of Madagascar, have a tradition of cemeteries outside settlements, but their decoration has changed substantially over time. Early in the

20th century, highly-decorated graves were reserved for royals. Their burials were marked large stone plots, and groups of carved wooden posts (aloalo) often over seven

feet high were inserted into them. On the platform’s surface were the horns of zebu cattle, the humpbacked breed raised in the area; these were from the zebu slain for the funeral feast. Cattle numbering 1000 were destined for the burial of a ruler who died in 1912; his grave and the 40 aloalo that were erected required six months of preparation. As the century advanced, wealthy individuals were permitted burials made in the same vein. The aloalo are often about six feet tall. Their stems are usually flattened openwork forms carved in geometric shapes that stress crescents and circles, perhaps references to the moon. The finial section often takes a figurative form. Earlier examples mostly depicted cattle, the livelihood of the Mahafaly, or birds (Fig. 394). Later posts include representations of the deceased performing a significant action that took place in his lifetime, or refer to noteworthy objects they encountered, such as an airplane or vehicle (Fig. 395).

As time went on, finial forms expanded (Fig. 396 A), the grave often was surrounded by a cement wall, frequently decorated with paintings, and a house-like structure might be centered within it (Fig. 396 B). As more Mahafaly became Christians, cement obelisks inscribed with crosses and names became de rigueur, their model the monuments from European graveyards (Fig. 396 C); these were also employed by the neighboring Antanosy. Additional late 20th-century Christian graves were still created as stone-topped platforms, miniature house forms bearing paintings of the deceased with crosses erected to the side (Fig. 396 D). Aloalo are still made, although they are usually finished with oil paint (Fig. 397).

Further Readings

Archdeacon, Sarajane. “Erotic Grave Sculpture of the Sakalava and Vezo.” Transition No. 12 (Jan./Feb., 1964): 43-47.

Baumanova, Monika. “Pillar Tombs and the City: Creating a Sense of Shared Identity in Swahili Urban Space.” Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress (April, 2018).

Bonetti, Roberta. “Coffins for wear and consumption: abebuu adekai as memory makers among the Ga of Ghana.” Res 61-62 (Spring-Autumn, 2012): 262-278.

Devisse, J., ed. Vallées du Niger. Paris: Reunion des Musees Nationaux, I993.

Gensheimer, Thomas R. “Research Notes: Monumental Tomb Architecture of the Medieval Swahili Coast.” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 19 (1, 2012): 107-114.

Kreamer, Christine Mullen. Inscribing power, writing politics. Washington, DC: National Museum of African Art, 2007.

Mack, John. “Tomb sculpture” entries. In Tom Phillips, ed. Africa: The Art of a Continent, p. 148. Munich: Prestel, 1995.

Morin, Floriane. “Bura Asinda-Sikka necropolis in Niger.” In African terra cottas: a millenary heritage: in the Barbier-Mueller collections, pp. 106-111; 427.

Nguyen Huu Giao, France-Aimée. “An Encounter with the Konso, the ‘People of the Aurora,’ and a Visit to Their New Museum.“ Tribal Art 15 (No. 58, 1, Winter, 2010): 110-115.

Otto, Shako. “Traditional Konso Culture and the Missionary Impact.” Annales d’Éthiopie 20 (2004): 149-180.

Secretan, Thierry. Going into darkness: fantastic coffins from Africa. London: Thames & Hudson, 1995.

Zhao, Bing. “Global Trade and Swahili Cosmopolitan Material Culture: Chinese-Style Ceramic Shards from Sanje ya Kati and Songo Mnara (Kilwa, Tanzania).” Journal of World History 23 (1, 2012): 41-85.

Effigies, Reliquaries, and Reliquary Guardians

Aside from tombs, there are other objects associated with the dead, some of which begin with the funeral. As mentioned, in the past many funerals took place after burial, since resources needed to be mustered and mortuaries did not yet exist. Some societies employed effigies of the deceased to serve as a focal point for the funeral, since the corpse itself had already been interred.

The Edo from Benin Kingdom would take some hair and nail clippings from the deceased to prepare for a post-burial funeral. Typically, they would then take kaolin “chalk” and mix these with it, modeling a simple human form, piercing the effigy for a woman, adding a penis for a man. At the funeral, the effigy would be “dressed” in cloth and placed on a draped bed for a lying-in-state. Prominent chiefs might have their effigy carved from wood and dressed in pure white cloth. These measures were taken only if the funeral were delayed; the ruler’s corpse, however, was never shown in state. Instead, the monarch’s effigy was prepared as a more carefully carved standing figure dressed with actual beads and cloth (Fig. 398). It was accompanied by courtiers and protected by a parasol during the final day of the commemorative ceremonies.

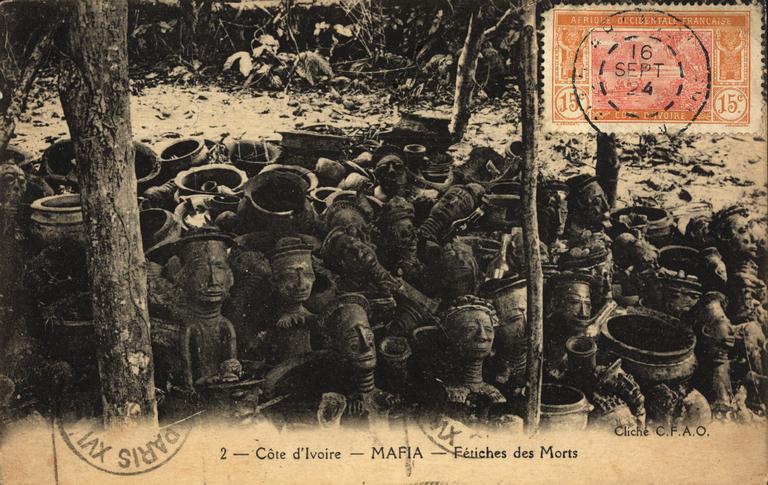

Most of the Akan peoples of southern Ghana and southeastern Côte d’Ivoire (including the Fante, Kwahu, some Asante and others) prepared terracotta pots (often with figurative elements) for funerals until the first half of the 20th century. These vessels–blackened or painted with red, white, and black stripes–held the hair from the family members’ shaved heads, evidence of mourning and cohesiveness; others held specially prepared foods to be shared with the deceased. The objects were left at the family’s “place of pots” (asensie) outside the community, not placed on the grave, with the following prayer:

Here is food.

Here are (hairs from) our heads.

Accept them and go and keep them for us (Rattray, 1927: 165).

Simple shapes were used by ordinary people, while the elite often had pots with relief elements that referred to proverbs or symbolic animals (Fig. 399). Frogs seem to have been a reference to the earth, the resting place of the deceased; pythons, whose colorful patterns are frequently associated with the rainbow, are alluded to in the proverb, “death’s rainbow encircles everyone’s neck.”

Fig. 400. These memorial terracottas come in a variety of styles, dependent on region. All have the lined neck that signifies an attractive feature in the region. Left to right. Upper Left: Queen Mother funerary terracotta head. Akan female or male artist (Adansi or Asante), Ghana, 18th century. H 15″. Detroit Institute of Art, 2006.148. Museum purchase; Ernest and Rosemarie Kanzler Foundation Fund. Public domain. Upper Middle: Funerary royal terracotta portrait head. Akan female or male artist, Ghana, late 19th or early 20th century. H 12″. Brooklyn Museum, 72.49.4. Gift of David R. Markin. Creative Commons CC-BY 3.0 US. Upper Right: Royal funerary terracotta head. Akan female or male artist, Ghana, 16th–18th century. H 12″. Yale Art Gallery, 2010.6.166. Gift of SusAnna and Joel B. Grae. Public domain. Lower row, left to right. Lower Left: Royal terracotta funerary head. Akan female or male artist, Ghana, before 1931. H 6.69″. © Trustees of the British Museum, Af1931,1118.51. Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Lower Middle: Terracotta head originally attached to a body. Anyi female or male artist, Côte d’Ivoire, 18th-19th century. 6 1/8″. Brooklyn Museum, 69.56. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Abbott A. Lippman. Creative Commons CC-BY 3.0 US. Lower Right: Royal funerary terracotta head. Asante female or male artist, Fomena, Ghana, 19th century. H 10.63″. © Trustees of the British Museum, Af1933; 1202.1. Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Akan royals formerly also used terracotta funerary effigies that date back to at least the 17th century, centering on those Akan groups south of the Asante. Both male and female artists constructed these heads (Fig. 400)–the most common form, ranging from a few inches high to life-size–or full figures. These abstracted portraits often included clues to gender and position through hairstyle, but were not usually individualized facially, other than through facial scarification marks. While some had flattened disc-shaped heads akin to those of the aku’aba figures (see Chapter 3.3), others were more naturalistically modeled.

With Christianization, the practice has sharply diminished, but the royal terracotta heads and figures might be carried on palanquins, displayed on thrones at funerals, and wrapped with kente cloth. They were usually accompanied by terracottas representing spouses, servants, and other family members; these not only provided an entourage such as that which surrounded a living royal, but may have replaced sacrificed slaves and favored courtiers who, in centuries past, chose or were chosen to accompany the deceased to the afterworld. After completion of the ceremonies, these heads or figures also usually were taken to the asensie and left there (Fig. 401). Many of these terracotta-filled spots since have been raided by those supplying art objects to collectors.

Most West and Central African groups have strong metaphysical attachments to the places their ancestors were buried, an event that usually accords them “ownership” of that area. Some ethnicities, however, are more recent immigrants to a region, having been pushed out of their homelands due to wars or other pressures. In Gabon, a number of ethnic groups are fairly recent

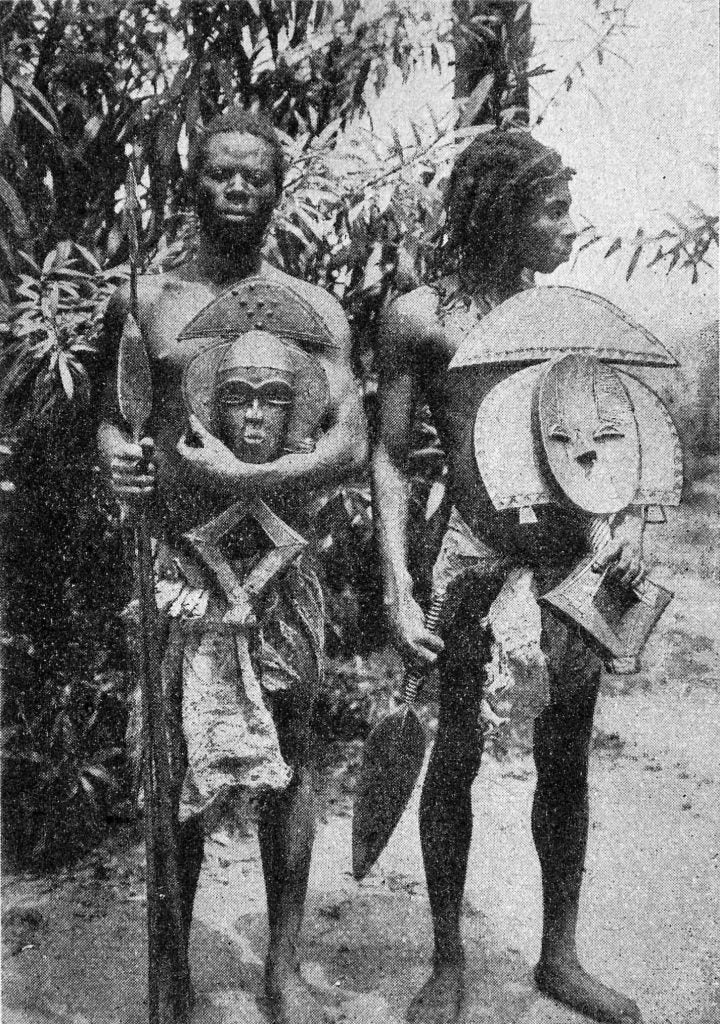

arrivals, having moved into their present territories in the 19th century from original settlements in Chad and the Central African Republic. When faced with migration, they created an ingenious solution–they disinterred the skulls and other bones of important ancestors and transported them to their new home, placing them in basketry, bark, or cloth containers watched over by a wooden or metal figure (Fig. 402). These reliquaries–the same word is used for medieval European containers that housed saints’ bones–thus are considered to have a guardian, for the figure does not represent the deceased. Missionaries and the French colonial government pressured the peoples involved to abandon the practice in the first decades of the 20th century. Although this is no longer a living tradition, the relevant art forms indeed live on–they are among some of the most faked objects in Africa, due to their appeal to collectors.

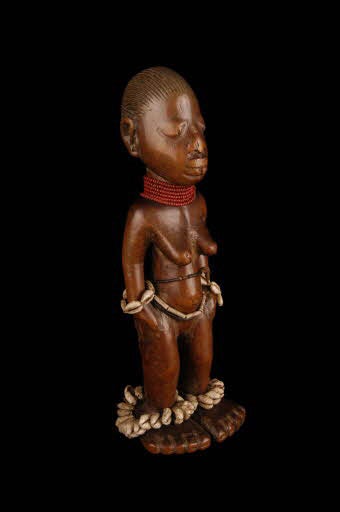

The Fang, who live in southern Cameroon and parts of Equatorial Guinea, as well as Gabon, honored both male and female ancestors with bark box reliquaries (byeri) topped either by heads in the center of their lids or by male or female figures perched on the lids’ edges (Fig. 403). Both had spike-like extensions that were inserted to keep them stable, but some of these were removed in Europe, for the container itself–the vital part of the ensemble

for the Fang–was usually discarded by collectors, as were feathered headdresses and jewelry (Fig. 404). The figures are bulbously muscular, with thick necks, rounded limbs, and short legs (Fig. 405). Their abstract faces frequently

including a heart-shaped depression, the mouth either a simple line on its lower edge or opened to show bared teeth (Fig. 406). The eyes were marked by brass disks that were originally kept polished. The ensembles were kept in dark areas of lineage leaders’ quarters and were sacrosanct–their gleaming eyes served as warnings to women and children to stay away. During initiation, newly-circumcised boys saw the exposed bones for the first time and watched a kind of puppet mime acted out by elders with the sculptures that had been temporarily removed from their sockets. Their curiosity about the forbidden once led new initiates or children told about the custom to create their own imitation byeri filled with monkey skulls, meant to bring luck. Actual ancestral reliquaries were a way of contacting these deceased family members and asking for their protection and blessings, consulting them on questions of importance, and discovering the causes of current problems.

Offerings were periodically made to the ancestors, their bones repainted red, with palm or resinous oil applied to wooden figures and heads that had originally been blackened with charcoal, oil from the seed of the tree Ongokea gor, and copal resin. Some of these sculptures appear to sweat, their surface having a sticky appearance.

Other groups from Gabon similarly protected their reliquaries with even more abstract figures. Although these were first made from wood, their bodies were armored with flattened brass and copper wire and sheet metal, expensive and sheet metal, expensive materials that honored the ancestors. The examples made by the Kota people are among the best-known of these works (Fig. 407). These pieces (mbulu ngulu) were made with both convex and concave faces (apparently by artists operating in the same region) and some were Janus-faced. Both abstract and more naturalistic figures were created (Fig. 408). The neck connected to a lozenge shape which was partially hidden when inserted into the relic basket; the upper part of the lozenge may have represented shoulders while the basket acted as “body.”

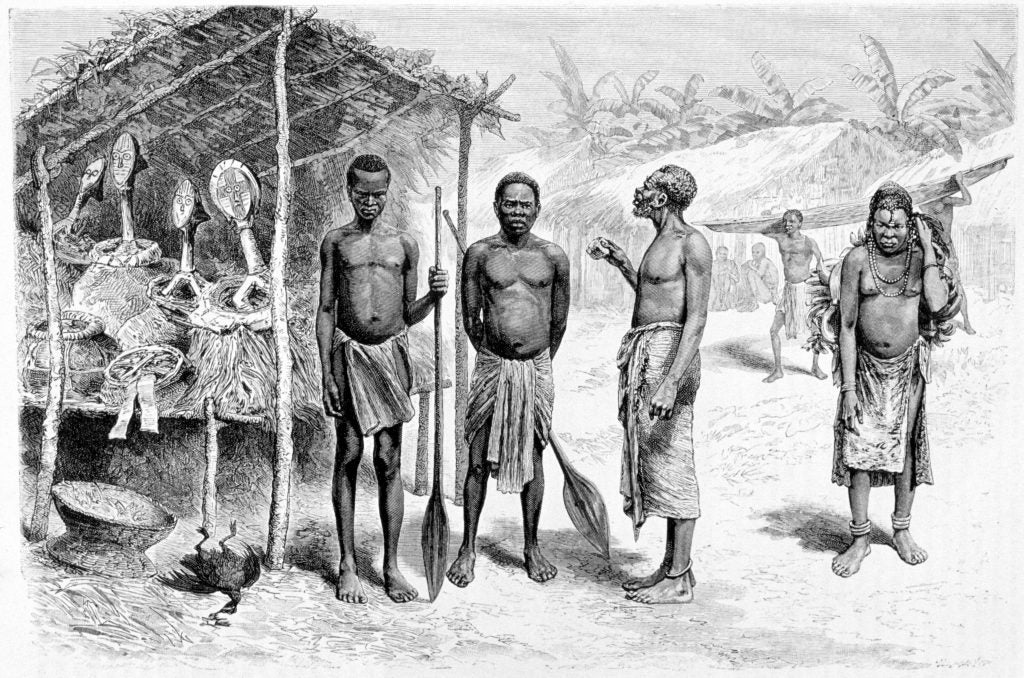

These ancestral reliquaries were stored in a communal shrine outside the community, meant to be accessed only by male initiates (Figs. 409 and 410).

urther Readings

Cole, Herbert M. and Doran H. Ross. The Arts of Ghana. Los Angeles: UCLA Museum of Cultural History, 1977.

Fernandez, James W. Bwiti: an ethnography of the religious imagination in Africa. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982.

Kaehr, Roland, Louis Perrois, Marc Ghysels and Rachel Pearlman. “A Masterwork That Sheds Tears… and Light: A Complementary Study of a Fang Ancestral Head.” African Arts 40 (4, 2007): 44-57.

Lagamma, Alisa, ed. Eternal Ancestors: The Art of the Central African Reliquary. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007.

Martinez, Jessica Levin. “Ephemeral Fang reliquaries.” African Arts 43 (1, 2010): 28-43.

Perrois, Louis, ed. Esprit de la forêt: terres du Gabon. Bordeaux: Musée d’Aquitaine/Paris: Somogy, 1997.

Rattray, R.S. Religion and Art in Ashanti. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1927.

Tessmann, Günter. “Die Kinderspiele der Pangwe.” Baessler-Archiv 2 (1912): 250-280.

Demanding Twins of the Yoruba of Nigeria and Benin Republic

Twins strain their mother’s biological system, and are usually born prematurely, placing their own survival at risk. While Western hospitals and incubators have vastly improved their odds of successfully evading infant death, that jeopardy remained strong throughout much of the 20th century. This was a particular problem for the Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria and the Benin Republic, for not only do they have the

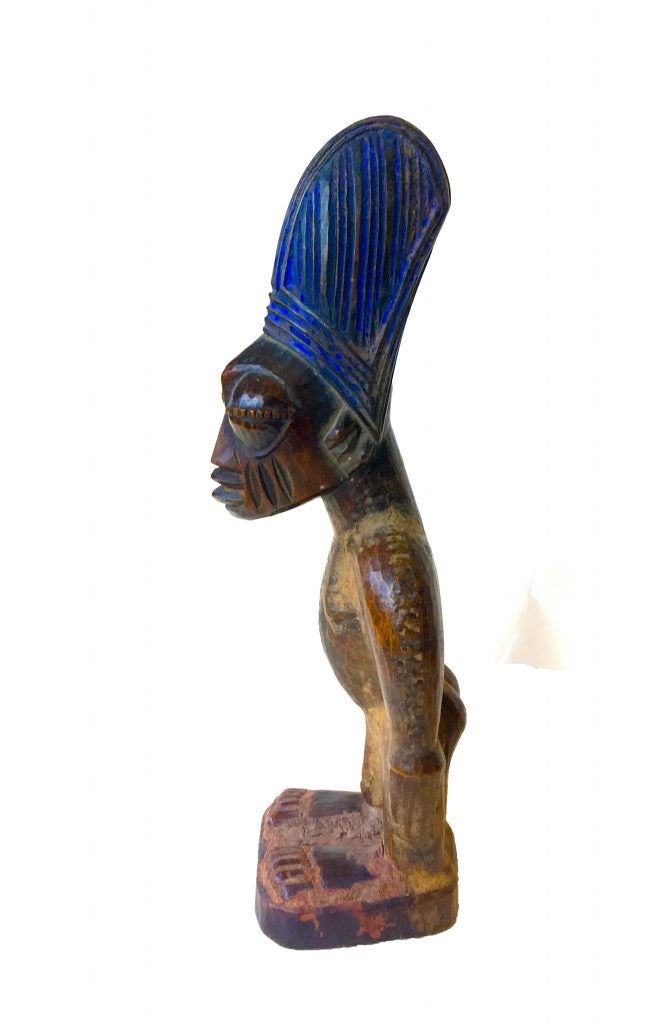

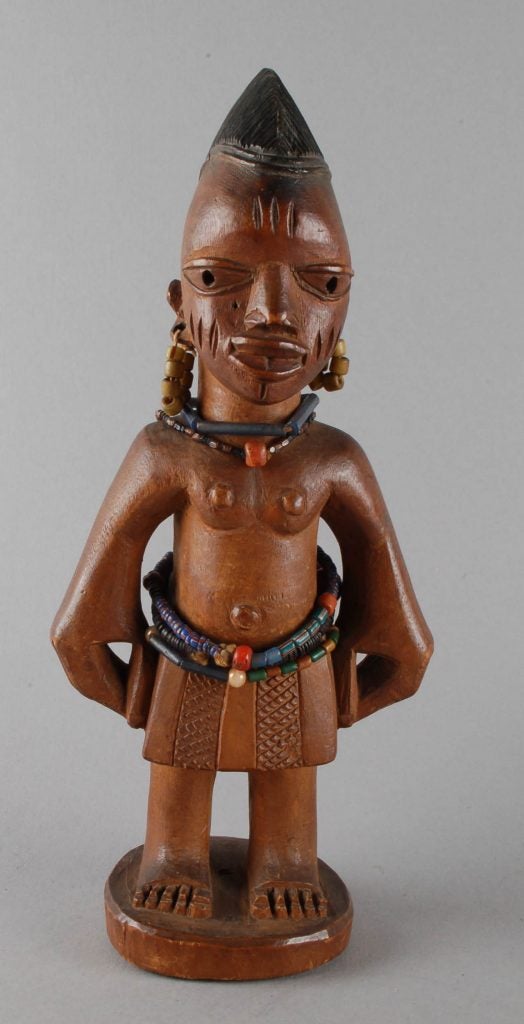

highest fraternal twinning rate in the world, their value for twins extends beyond affection to the supernatural blessings and maledictions twins are able to exert. In many parts of West Africa, twins are valued and considered to have a spiritual dimension unshared by other children. The Yoruba associate them with the ability to bring wealth and other blessings to the family if they are satisfied, and to visit misfortune upon family members if they are not. For living twins, this often means twins receive little treats to keep them content, and are cajoled more than their siblings when upset. However, efforts to keep twins happy are not restricted to living twins, for their powers do not diminish in the afterlife. If Taiwo (the first-born, but considered the junior child, sent by its twin to test the world’s sweetness) and/or Kehinde (the second, but senior, twin) die, their mother will seek a diviner’s advice as to what steps she should take next (see Chapter 3.6). This often led to the prescription of a carved

wooden statue (ere ibeji) to stand in for the deceased twin or twins (Fig. 411).

If one twin lives and wears metal or beaded ornaments that link it to the family deity, its twin’s figure bears these adornments as well. If the mother feeds the living baby, she lightly smears food on the lips of the ibeji figure. When she bathes the living twin, she bathes the statue, and afterward applying oil to both. In the past, red camwood powder was applied to keep babies dry, and many ibeji figures show its presence in unhandled crevices (Fig. 412). When the baby is put to bed, the figure is placed in a horizontal position. When the mother backs the living twin, the figure is tucked into the front of the carrier cloth. Constant handling may erode the carvings’ crisp details; well-loved twin figures begin to lose their facial features (Fig. 413).

Ibeji figures constitute the largest body of Yoruba art. While not as common as they once were, they are still made and used, especially in rural areas. Non-traditional religions have gradually altered ibeji practices; Muslim Yoruba used to freely have ibeji carved, the figures including triangular Islamic amulets at the neck (Fig. 414). Today, in cities where Islam or Christianity

dominate social life, traditional objects are sometimes seen as countrified. Some mothers now substitute plastic dolls for carved wood, or have a living twin photographed and duplicated in a single print so that some surreptitious care can still take place.

These practices continue as long as the deceased twin or twins deem it necessary; they communicate their wishes through the diviner and may be satisfied within a few years of care–or continue to insist on

loving treatment even after the mother dies, passing the obligation to another family member. Once twins accept an honorable retirement, their depictions may be kept at home or taken to a shrine for the deity Shango, the father of twins (see Chapter 4.1).

Ibeji figures are fairly small and depict standing figures on a base, their arms at their sides (Figs. 415). Frontal, the head dominates their proportions, which is stylistically consistent with other Yoruba art. Similarly, the eyes are large within the face, the pupil sometimes marked with a nail or drilled hole. The lips normally are carved as two rectangles or curving rectangles that do not meet at the corner. Facial marks of the specific community are clearly marked on the cheeks, and the hair–often

dressed in a high conical form that alludes to the inner head, site of destiny, is darkened with indigo or the brighter blue of imported laundry blueing (Fig. 416). An occasional figure will wear a carved loincloth (Fig. 417), but normally ibeji are depicted nude, although they sometimes are covered with actual cloth. Their nudity clearly shows that these are adult figures: the male has fully formed genitals, the female has breasts. Yet ibeji are never carved for adult twins who die–they are made strictly for infants or small children. Their adult appearance is an inverted example of ephebism–the child is shown as a full adult, an exercise in idealism, represented as the adults they never became.

Honoring ibeji with garments pleases them because it enhances their status. Tunics with rows of sewn-on cowrie shells (Fig. 418), the old currency, are a sign of wealth. Some twins wear beaded garments and caps (Fig. 419), a sign they are royal family members, for only the monarch and those he favors can wear beaded attire.

Further Reading

Bordogna, Charles. “Ibeji surface analysis.” In Leonard Kahan, ed. Surfaces: color, substances, and ritual applications on African sculpture, pp. 262-271. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009.

Claessens, Bruno. Ere ibeji: Dos and Bertie Winkel collection. Delft, Netherlands: Elmar, 2013.

Drewal, Henry J., John Pemberton III with Rowland Abiodun. Yoruba: Nine Centuries of Art and Thought. New York: Center for African Art, 1989.

Houlberg, Marilyn. “Ibeji Images of the Yoruba.” African Arts 7 (1, 1973): 20-27, 91-92.

Joubert, Hélène. Ibeji: divins jumeaux = divine twins. Paris: Somogy, 2016.

LaGamma, Alisa. “Yoruba Dualities.” In Echoing images: couples in African sculpture, pp. 23-27. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.

Lawal, Babatunde. “Sustaining the oneness in their twoness: poetics of twin figures (ère ìbejì) among the Yoruba.” In Phil M. Peek, ed. Twins in African and diaspora cultures: double trouble, twice blessed, pp. 81-98. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011.

Oruene, Taiwo. “Magical Powers of Twins in the Socio-Religious Beliefs of the Yoruba.” Folklore 96 (2, 1985): 208-216.

Pemberton III, John, John Picton and Lamidi O. Fakeye. Ibeji: The Cult of Yoruba Twins. Milan: 5 Continents, 2003.

Renne, Elisha P. “Twinship in an Ekiti Yoruba town.” Ethnology 40 (1, 2001): 63-78.

Sprague, Steven. “Yoruba Photography: How the Yoruba See Themselves.” African Arts 12 (1, 1978,): 52-59, 107.

Thompson, Robert Farris. “Sons of Thunder: twin images among the Oyo and other Yoruba groups.” African Arts 4 (3, 1971): 8-13, 77-80.

Renne, Elisha P. “Twinship in an Ekiti Yoruba Town.” Ethnology 40 (1, 2001): 63-78.

Funerary Masquerades and Ancestors of the Dogon of Mali

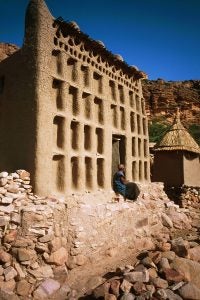

Masquerades are essential to the funerary rites of some of the Dogon of Mali–eligible adult men. The Dogon live in small communities where all residents know each other and death impacts everyone in a personal, interconnected way. Death produces amorphous, dangerous energy that can

harm the living and their crops. Bodies are not buried within the community, but wrapped in a blanket and transported to ancient caves in the cliff face of the steep Bandiagara Escarpment. These caves were earlier

used by the Tellem, “little people” who lived in the region from the 11th-16th centuries, their presence

overlapping with the arrival of the migrating Dogon for about a century. The Tellem apparently lived at the foot of the escarpment, but stored their grain up on the cliff face. They used old granaries (Fig. 420) or the caves as a depository for cloth-wrapped corpses and their personal goods such as headdrests, clothing, tools, and kitchen goods, as well as ritual pottery, sealing these off afterward. Centuries of use in some caves yielded skeletal remains of up to 3000 people. The Dogon similarly use the caves for their unburied dead, hoisting them with ropes up the nearly vertical cliff.

Dakar-Djibouti.

Not all Dogon avail themselves of traditional funerary rites, for many converted to Christianity or Islam in the later decades of the 20th century, and follow the burial traditions of those faiths. For those men who still celebrate a traditional path, however, the actual death is not marked with great ceremony, except for particularly venerable people (Fig. 421). In decades past, the huge Great Mask (Fig. 422)–carried but never worn–was removed from its hiding niche in the cliff and leaned against the house of the deceased. A performer then danced with it, holding it in his hands. This practice, however, seems to be defunct in most villages. The Great Mask itself represents a mystical snake; once, the Dogon say, humans did not die, but transformed into snakes when they reached an advanced age. One elder was interrupted during the process, however, and, startled, spoke–a forbidden act during transformation. Thus death came to the Dogon. The Great Mask (and, subsequently, all other masks) commemorated the event and acted as a sort of lightning rod to gather any negative energy surrounding death, taking it away from the community. The Great Mask also provided a sense of historicity; a new one is carved every 60

years when the sigi festival takes place, marking a change of generations. Old and new Great Masks are kept in a cliffside sanctuary.

Even when the Great Mask remains in its sanctuary, the funerals of notables are marked. The blanket that transported their body to the cliffs is placed near a broken calabash and the deceased’s personal implements, becoming the focal point of a one-day ceremony that brings masked performers into the village. Few individuals enjoy this immediate ceremony. Most deaths share a joint funeral called dama, which is only held every few years for about six days–a collective practice that differentiates Dogon traditional funerals from those of most African groups. The dama celebrates all those who have died since the last dama took place, and shares thus sharing expenses among several families. It is meant to escort the spirits of the dead from the village–partially accomplished through mock battles and rifle fire that suggest the spirits are not eager for the transition. Masqueraders are instrumental in this process, for they accompany the spirits to the other world, dancing on the roofs of those who have lost a relative–mortuary cloths are hung from those roofs–then moving into the village plaza and eventually dancing out of the community’s sight with their invisible companions, now translated into full ancestors.

Perhaps only men are honored by masqueraders because all circumcised, initiated men typically belonged to the awa masquerade society that existed in each village. The awa owns and performs the masquerades. The types any village owns vary, but certain popular ones consistently appear out of the 78 different masquerade types that were recorded in the 1930s. Some are non-objective, while others have human or animal appearances. The number that appear at any given dama vary according to the importance of those who have died, the degree to which Islam or Christianity have displaced traditional religion, and the relative wealth of the inhabitants. Women, concerned with becoming barren, watch the male dama from rooftops or promontories at a safe distance. There are dama for deceased females as well, but they occur without masquerades.

One tall, plank-like mask called sirige (Fig. 423)–which is made from one piece of wood–only appears at the immediate funeral and dama celebrating a man who participated in the sigi rite, an event involving the awa society that only occurs every 60 years. It is the tallest of the masks, made from one tree, and dancing with it requires great dexterity and strength, since the performer touches its tip to the ground in a gesture of respect to the deceased, then must right it again, making circular movements. Although it is attached to the back of his head, he also bites down on a stick within the mask to aid control. Sirige‘s meaning varies

according to the Western scholars who researched it–or according to the Dogon villagers who interpreted it for them. For the French school of scholars, who depended on a specific Dogon man from the Sanga region for most of their information, the mask’s stacked layers represent multitudes of stars–of galaxies–ad infinitum, as well as journeys between the heavens and earth. At the same time, the same individual stated the repeated divisions represent the multi-storied ginna houses that mark each lineage, and some scholar’s interpretations are more likely to limit its meaning to a lineage’s many generations. Structurally it bears some resemblance to the Great Mask, as well as to masks worn by some of the Mossi of Burkina Faso, who belong to the same Gur language group, and may share a common (if distant) origin.

The most numerous mask type at a typical dama is that of the kanaga (Fig. 424), whose performers dramatically sweep their headpiece against the ground as they dance in unison. It is atypical of most African masks in that it is made from more than one piece of wood. While the face covering and vertical strip constitute a single carving, the crossbars are carved separately and attached, as are their short “arms” and “legs”, which are sewn onto the main structure. At least in the well-studied Sanga region, these are typically painted black and white. While the mask’s superstructure resembles the abstract arrangement of lizard or crocodile legs common in West African depictions, French researchers were first told it represented a black and white bird, then that it represented the Supreme Deity Amma, the upper bar simultaneously his arms and an allusion to the sky, while the lower bar dually was the earth and Amma’s legs. Each Dogon mask has a myth of origin and similarly probably has several interpretations, based on the levels of knowledge that are developed from entry into the masquerade society to elderhood within it. Variations in meaning and execution from one village or region to another are also probable.

Some young Dogon men who belong to the awa society dress in costumes and masks that transform them into the nomadic Fulani women that traverse the region with their cattle and family. Others wear masks that represent other human characters, such as hunters, members of additional ethnic groups and more. One of the most significant is the mask called satimbe, which bears a female figure as its superstructure (see Fig. 425) and is the only wooden mask that includes a female depiction. She represents both a particular woman from the distant past and a set of contemporary women born during the sigi celebration who are distinguished by being called the “sisters of the mask”. They are the only women to red fiber costumes in post-death preparations, have masks danced at their brief funeral, and later have masqueraders appear at their dama. The commemorated woman on the mask, Yasagine, was the first Dogon woman to see masking, then performed by another ethnic group. She stole the secret of masquerading from them, and created red fiber costumes for herself and fellow women performers, but was later tricked out of the secret by the males of her community. Her representations range from older, very geometric works to more naturalistic versions.

Animal masks abound: hares (Fig. 426), antelopes (Fig. 427), monkeys of various types, birds, lions, hyenas, baboons, and more. Most have similar sections that cover the dancer’s face, geometric constructions with deep channels marking the eye sockets, the eyes themselves carved through as rectangles or triangles. Like most Dogon maskers, the performers wear fiber skirts and attachments, the sides and backs of their heads concealed by a striped fabric hood. Animal mask origin myths refer to the ways hunters tried to placate the spirits of the animals they had killed, and the dancers often mime their movements and attempts to escape. The walu antelope dancer lowers his horns and charges other maskers, then limps and falls as if shot, while the hare performers hide from the hunter and collapse at the end of their performance. At the same, French researchers suggest, these animals are part of the cosmic mythology relating to creation’s beginnings, the antelope tasked with guarding the sun’s path, while the hare was one of three animals (each symbolizing the peoples of three geographic subregions with ritual alliances) who ate an early impure grain harvest.

Dama performed in the 1930s varied in number from 74 to several hundred masqueraders per

village, but numbers had decreased by the 1980s, where villages might have four to seven masked dancers. Some communities, such as the Muslim community of Songo, last held a dama in the late 1950s. Those masquerade appearances persisting today, however, do not occur wholly as periodic efforts to send the deceased to an ancestral afterlife. Limited but growing adventure tourism has brought outsiders into the previously remote Dogon regions, and abbreviated dama-like displays are now paid theatrical performances, with a significant number of dancers in fresh costumes providing photo opportunities.

Once a non-theatrical dama transforms the dead into ancestors, they join their predecessors to receive sacrifices at altars in the ginna, the home of the lineage head (Fig. 428). There they are represented by a pot, and sacrificed to in the hope that they will assist their living descendants, particularly to ensure a good harvest. Figurative sculpture can also be kept at these altars.

Additional Readings

Bedaux, R. M. A. “Tellem and Dogon Material Culture.” African Arts 21 (4, 1988): 38-45; 91.

van Beek, Walter E. A., R. M. A. Bedaux, Suzanne Preston Blier, Jacky Bouju, Peter Ian Crawford, Mary Douglas, Paul Lane and Claude Meillassoux. “Dogon Restudied: A Field Evaluation of the Work of Marcel Griaule [and Comments and Replies].” Current Anthropology 32 (2, 1991): 139-167.

Davis, Shawn R. “Dogon Funerals.” African Arts 35 (2, 2002): 66-77; 92.

Ezra, Kate. Art of the Dogon. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988.

Griaule, Marcel. Conversations with Ogotemmêli: An Introduction to Dogon Religious Ideas. New York: Oxford University Press, 1965.

Griaule, Marcel. Masques dogons. Paris: Institut d’Ethnologie, 1938.

Imperato, Pacal James. “Contemporary Adapted Dances of the Dogon.” African Arts 5 (1, 1971):. 28-33;68-72; 84.

Imperato, Pascal James. Dogon Cliff Dwellers. New York: L. Kahan Gallery, 1978.

Lane, Paul J. “Tourism and Social Change among the Dogon.” African Arts 21 (4, 1988): 66-69; 92.

Richards, Polly. “Masques Dogons in a Changing World.” African Arts 38 (4, 2005): 46-53; 93.

Egungun Ancestral Masquerades of the Yoruba of Nigeria and Benin Republic

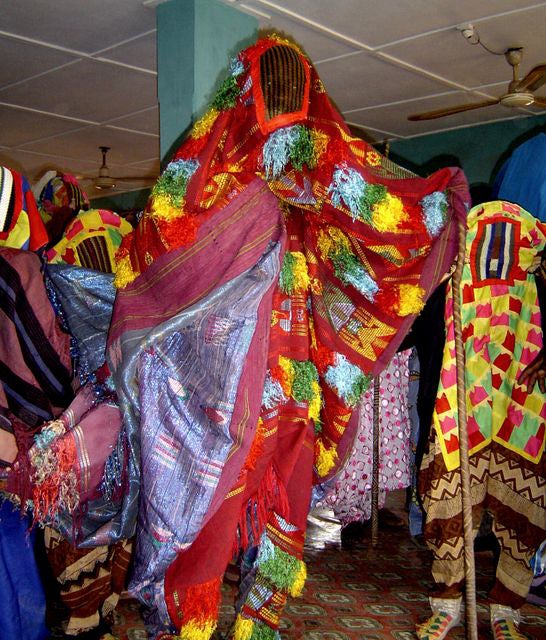

If the Dogon have masquerades performed to escort the ancestors to the other world, Yoruba egungun masquerades bring the ancestors back to this world.

Young men of a lineage don costumes and allow the ancestors to take them over, incarnating them in a concrete form so they can dance with their families, listen to their pleas, and offer their blessings. Family egungun appear at family funerals, but the egungun from the entire town participate in an annual festival, an opportunity to show family solidarity and compete with a show of splendor, expensive cloth, and vigorous dancing. They also appear when an important visitor comes to town, or for community project launchings.

Although the Yoruba, one of the largest ethnic groups in Nigeria, have many masquerade varieties, egungun is the only universal type–it can be found throughout Yorubaland, albeit in differing visual guises (Fig. 429). Nonetheless, its origin is agreed to have been the kingdom of Oyo, to the north of Yoruba territory, There the 19th-century Yoruba historian and missionary Samuel Johnson, himself from Oyo, stated the tradition had been adopted from the Nupe, their neighbors to the north. While the Nupe have cloth masquerades, they do not represent ancestors. Rather, they are witchfinders, as the most important of the royal egungun in Oyo still are. Witchfinding egungun lack the luxury ingredients and colorful juxtapositions of other masqueraders; instead, they tend to be loaded with medicine (Fig. 430) and speak to power rather than aesthetics.

At some point, ancestral incarnations became the focus of the performance and the masquerade spread to other kingdoms through war, trade, or the desire to emulate Oyo’s power and wealth. While we don’t know when this happened, British traveler Hugh Clapperton visited Oyo nearly 200 years ago in 1826 and saw a performance for the monarch that involved a multitude of ancestral egungun, “dressed in large sacks,

covering every part of the body; the head most fantastically decorated with strips of rags, damask silk, and cotton, of as many glaring colours as it was possible.” He stressed the acrobatic nature of the dancing, and also observed a second aspect of the masquerade: the appearance of non-ancestral costumed entertainers known as idan egungun, or miracles. These side attractions are meant to both entertain spectators and impress them with the power of the ancestors. Clapperton viewed performers occupying a giant snake, having mysteriously exited other costumes; he also viewed the performance of a European, who mimed taking snuff and walked around the performance area gingerly. Idan egungun today still include the snake (Fig. 431), as well as a variety of other performances, including dancing mats, Europeans kissing, dancers dressed as women (Fig. 432), or caricatures of non-Yoruba.

Only a few egungun have wooden masks (Fig. 433).

Most of these are associated with witchcraft or those representing deceased hunters. The latter usually show hunters with a hairstyle typical of their past–a loose transverse plait, often with medicinal calabashes tied along the hairline (Fig. 434). Others, from the city of Abeokuta, are more fanciful, depicting the hunter with extended hare-like ears, his forehead again covered with tiny calabashes full of medicines to protect him from animals and the potential spiritual attacks of the forest (Fig. 435). This masquerade headpiece type seems to have originated in the workshop of Oniyide Adugbologe (ca. 1875–1949). On these headdresses, the hunter usually bears a double-headed drum between his ears–the type played by praise singers who might have followed him during his lifetime, since hunters were culture heroes who supplied communities with meat. Behind the drum is a hare or other wild animal, a reminder of the hunter’s prey.

Most egungun, however, are made entirely from cloth, ranging from tight-fitting costumes that cover the head to sack-like configurations to large ensembles with layers of hanging flaps. Some are displays of conspicuous consumption, employing 20 or more yards of expensive fabric such as damask or velvet, dragging it through muddy or dusty streets to show disdain for the expense. Others are of more common fabrics, but often arranged in surprising color combinations or employing a patchwork section on the torso (Fig. 436), a juxtaposition never seen in everyday clothing. The cloth is often contributed by women–although male tailors created the costume–and includes hand-woven Yoruba fabrics as well as imported cotton prints, brocades, cotton laces, and velvets.

A crocheted panel allows the performer to see out while keeping his identity concealed, which is critical–hands are either gloved or, like feet, enveloped in cloth; the latter may also be shod. Cowries–indicative of wealth–or beads may further decorate the viewing panel (Fig. 437), and colobus monkey fur may be attached, since numerous legends attribute the first egungun to this primate, who was advised to create it by a diviner. The most imposing egungun (Fig. 438) are covered with lappets of cloth. Since new layers are added to keep their appearance fresh, they are veritable textile museums, each layer revealing older cloths. These can be box-like in structure, the cloth supported by a hidden tray-like headpiece (Fig. 439). Many of the lappets have sawtooth edging, its meaning ambiguous–although the pattern even appears on the hare-like ears of many of the wooden hunters’ egungun headpieces. Others are hung with metallic bits–sometimes reflective cut-outs, sometimes coins, occasionally Catholic saints’ medals, from a family who had been enslaved in Brazil, then returned to Nigeria after emancipation and incorporated egungun and their adopted religion. The ability to “shine” in performances–which take place in daylight–is shared by many of these masquerades, whether through metal additions, the sequins that characterize egungun from Benin Republic (Fig. 440), or varied types of high-contrast juxtapositions of color (Fig. 441).

Another key aspect many egungun share is their transformative nature. Sack-like costumes are manipulated into different shapes (Fig. 442), while cape-like additions may be removed and twirled

independently (Fig. 443), and some outfits are turned inside out and thus change color (Fig. 444), among other shifts. These are again evidence that the ancestors’ powers have grown to surpass any abilities they had when living. Their family members dance with them, praise them, and make requests or ask questions, demonstrating their belief that more than human agency is at work.

Further Reading

Abiodun, Rowland. Yoruba art and language: seeking the African in African art. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Aremo, P. S. O. “Between myth and reality: Yoruba Egungun costumes as commemorative clothes.” Journal of Black Studies 22 (1, 1991): 6-14.

Drewal, Henry John. “The arts of Egungun among Yoruba peoples.” African Arts 11 (3, 1978): 18-19; 97-98.

Drewal, Henry John. “Pageantry and Power in Yoruba Costuming.” In Justine M. Cordwell and Ronald A. Schwarz, eds. The fabrics of culture: the anthropology of clothing and adornment, pp. 189-230. Chicago: International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences, 1973.

Drewal, Henry John, John Pemberton III with Rowland Abiodun. Yoruba: Nine Centuries of African Art and Thought. New York: Center for African Art, 1989

Drewal, Margaret Thompson and Henry John Drewal. “More powerful than each other: an Egbado classification of Egungun.” African Arts 11 (3, 1978): 28-39; 98-99.

Famule, Olawole Francis. “Art and Spirituality: The Ijumu Northeastern-Yoruba Egungun.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, 2005.

Houlberg, Marilyn. “Egungun Dancers of the Remo Yoruba.” African Arts 11 (3, 1978): 20-27; 100.

Houlberg, Marilyn. “Notes on Egungun among the Oyo Yoruba.” African Arts 11 (3, 1978): 56-61; 99.

Lawal, Babatunde. “The living dead: art and immortality among the Yoruba of Nigeria.” African Arts 41 (4, 2008): 26-31.

Noret, Joël. “Between authenticity and nostalgia: the making of a Yoruba tradition in southern Benin.” African Arts 41 (4, 2008): 26-31.

Pemberton, John. “Egungun Masquerades of the Igbomina Yoruba.” African Arts 11 (3, 1978): 40-47; 99-100.

Poynor, Robin. “The Egungun of Owo.” African Arts 11 (3, 1978): 65-76; 100.

Schiltz, Marc. “Egungun Masquerades in Iganna.” African Arts 11 (3, 1978): 48-55; 100.

Thompson, Robert Farris. African Art in Motion. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974.

Wolff, Norma Hackleman. “Egungun Costuming in Abeokuta.” African Arts 15 (3, 1982): 66-70; 91.

Funerary Practices and Burials of the Kongo Peoples

Although traditional Kongo religion places an all-powerful High God above everyone, he was not worshipped at temples or through a dedicated priesthood. Instead, grassroots beliefs in the supernatural centered around the dead: the nkisi that use spirits of the deceased to do human bidding (discussed in Chapter 3.5), and family ancestors. Elaborate funeral practices

and burials past and present mark the ancestral passageway, one step on the Kongo cycle of birth-life-death-afterlife-reincarnation, a cosmogram often expressed as a crossed circle or a diamond. Not every Kongo sub-group has identical funerary arts, nor have some practices remained unchanged over the centuries. Still, certain ideas about the cycle of life and how high status requires special funerary preparations and post-funerary treatments persist.

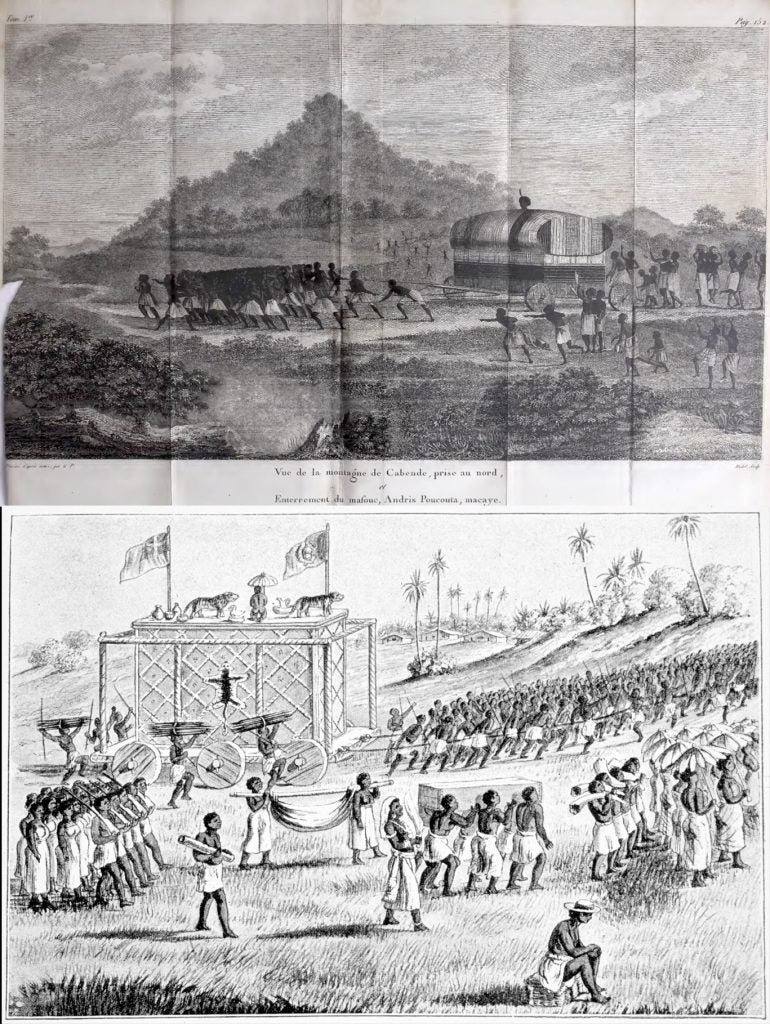

Mats made to wrap corpses often included depictions of the Kongo cosmogram (Fig. 445), a matter-of-fact symbol that accepts death’s inevitability but optimistically includes reincarnation/rebirth. In a display of conspicuous consumption, the bodies of important individuals were often wrapped in many layers of cloth as well as mats, a practice that continued over time but is no longer active (Fig. 446, above). In images from the southern Kongo coastal region–created about a century apart–the corpses of high-ranking leaders were taken to the grave in huge carts constructed by European carpenters and wheelwrights, accompanied by musicians and mourners. The cost was born by their successors (often a maternal nephew since the Kongo are matrilineal) and might require years of preparation, during which time the body was desiccated over a low fire to prevent rotting. The 18th-century version bore a representation of the chief’s head at the top, the cloths decorating the huge bundle having previously been displayed at his funerary bier. The whole structure was taken to the grave and buried, the site marked by two ivory tusks. Andrew Battell, an English trader who visited the royal cemetery just outside the Kongo capital of Mbanza Kongo somewhere between 1590–1610, noted the whole of the burial site “is compassed round about with elephants’ teeth pitched in the ground, as it were a Pale [picketed enclosure], and it is ten roods in compass [14 to 20 yards in circumference].” By the 1870s, even royal graves were marked by a single tusk.

The late 19th-century cortege (Fig. 446 below) similarly required a huge number of men to pull the funerary cart, which was two years in the making. It included two stuffed leopards at the top, as well as a civet skin affixed to the side–symbols of royalty. Like the other cart, a representation of the deceased’s head protruded above, but was shaded by a parasol, surrounded by vessels and utensils. The empty palanquin that once carried the chief was borne by his former attendants, and his wives walked in front of musicians with ivory sideblown trumpets. An honor guard with rifles and other mourner followed.

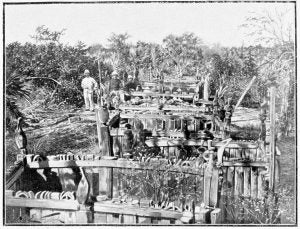

The Kongo-Bwende, a northern Kongo people who live along the border between Republic of Congo and Democratic Republic of Congo, also formerly desiccated the bodies of important men and women. They too swathed the corpses in cloth and mats–sometimes over a hundred of the former–but within a cane framework in human form

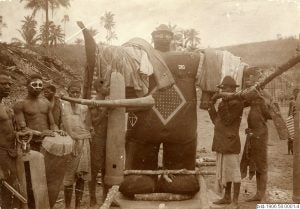

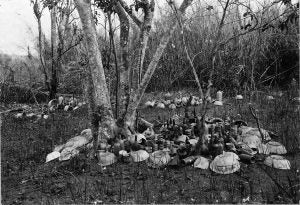

rather than a cart. The encased corpse, enveloped in a gigantic stocky figure, had a red blanket as its final “skin”. The resultant construction, known as niombo, towered over its human escorts (Fig. 447). The niombo had one arm gesturing up, the other down, refers respectively to the fullness of life and the transition to ancestorhood; the cosmogram was sometimes inscribed on its chest. Placed on a kind of litter, it was escorted to its grave by mourners and musicians, then buried. Some examples without corpses–both full size and in miniature–were made for Swedish missionaries stationed at Kingoyi in the early 20th century (Fig. 448), but this burial practice appears to have died out by mid-century. Cemeteries have been a norm for most Kongo peoples for centuries, unlike many parts of Africa. Locating burials outside the community seems to have had its basis in beliefs that the dead should be kept at a safe distance from the living so they translate to ancestorhood rather than linger in the human world. In the 19th century, burial sites often were decorated with grave goods, particularly utensils, bottles, and vessels used by the deceased in their lifetime (Fig. 449).

These were felt to have absorbed some of the deceased’s spirit, and alluded to the watery world of the dead in multiple ways: glass, white porcelain, and white shells have shiny, reflective surfaces that act as synonyms for water, and the whiteness of the last two object types is the color of mourning and the dead, shared with white kaolin/chalk. Some of the vessels on the grave have broken bottoms, a reference to the breaking of life. Grave goods tended to be enclosed by a border, marking what would have been the horizontal placement of the body. This was intended to both protect the living from the power of the dead–the grave is considered a form of nkisi–and to shield the spirit of the deceased from negative forces. These old grave forms usually were accompanied by tree planting. Ordinary citizens were directed to the other world by the trees’ burrowing roots. Rulers’ graves were marked by a specific tree type (Fig. 450) whose name punned on the Kongo words for “king” and “power”, assurances they would live again.

The Kongo-Boma had a gravesite practice operating from about 1850-1930 that varied substantially from that of other Kongo peoples, using a medium that was extremely rare in sub-Saharan Africa: stone. Men and women of importance–and many gained importance in this area along the Zaire River, which was a major trade region during the period–had graves marked with soft soapstone figures. Though often called ntadi, they are more accurately known as tumba(from the Portuguese word for tomb) or kinyongo, both terms also referring to ceramics or other items placed on a grave. While those who commissioned them presumably felt they would serve as permanent markers, over 500 were carted away to European and Democratic Republic of Congo museum collections by the 1970s. If this isolated tradition indeed had its origins in the elaborate tombstone sculptures of 19th-century Europe, the results were acclimatized by local taste and regional concepts of status. Regular categories existed: the mother-with-child, the crosslegged male with head in hand (Fig. 451), the hunter, the drummer. However, some are very idiosyncratic, including inscriptions with names and death dates (indications of literacy), figures praying before a crucifix, execution scenes, or figures in exotic European dress.

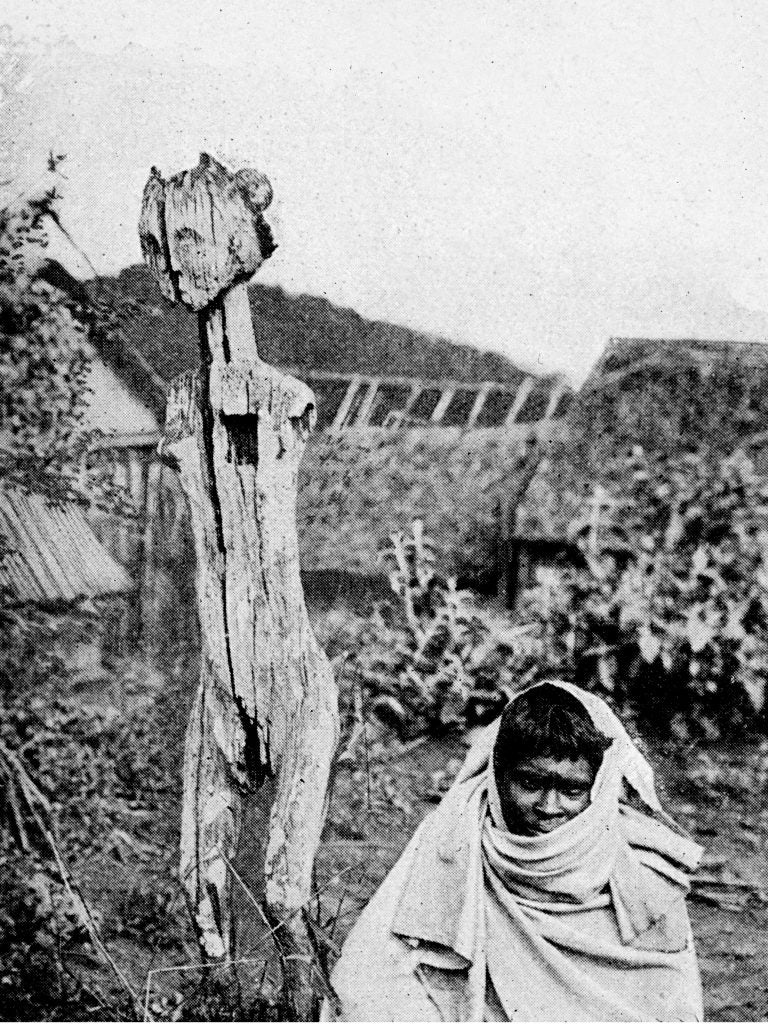

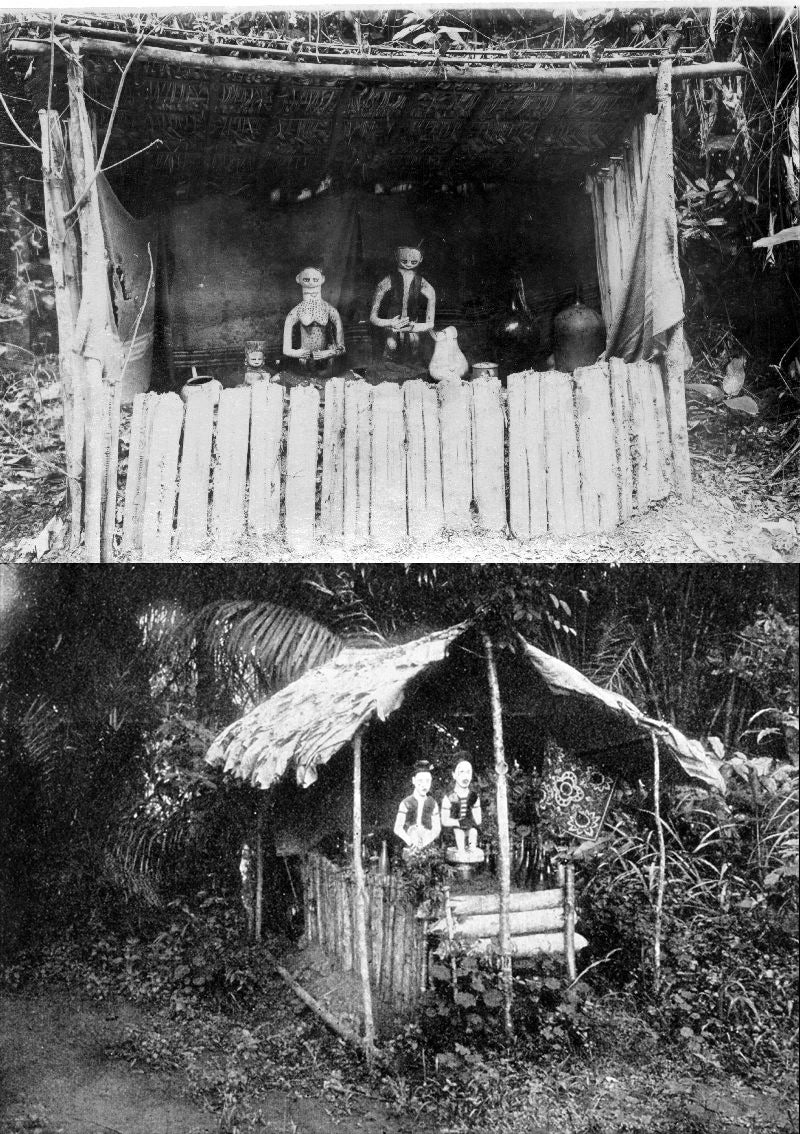

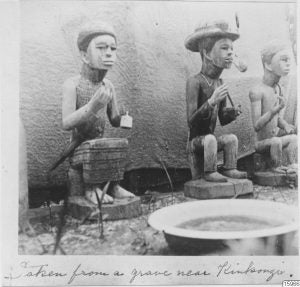

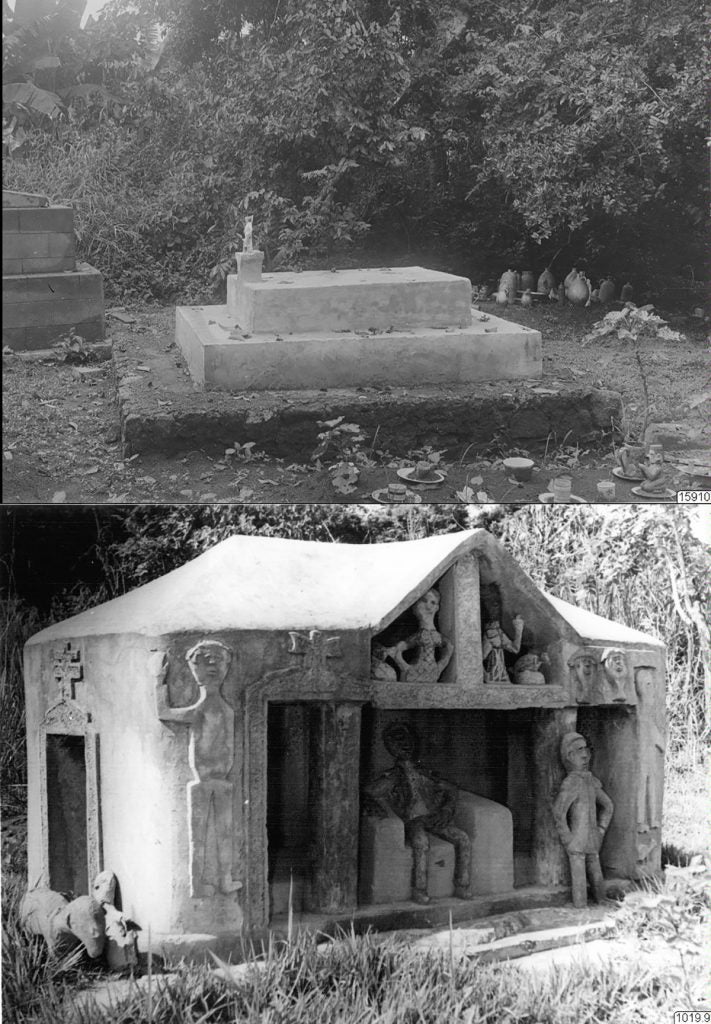

While other Kongo peoples had no tradition of stone grave sculpture, the Kongo-Yombe did mark the burial spots of notables with wooden sculpture (Fig. 452). While the date this custom began is unknown, the practice was ongoing in the late 19th and early 20th century. Miniature palisaded thatched houses, open on one side, were erected over the grave and offerings of food and drink were left for the deceased.

Figures of men and women, their skin painted white, the color associated with the watery world of the dead (Figs. 453 and 454) were within. Many featured men wearing Western pith helmets, trousers, or jackets–“new men” with access to the colonialist cash economy.

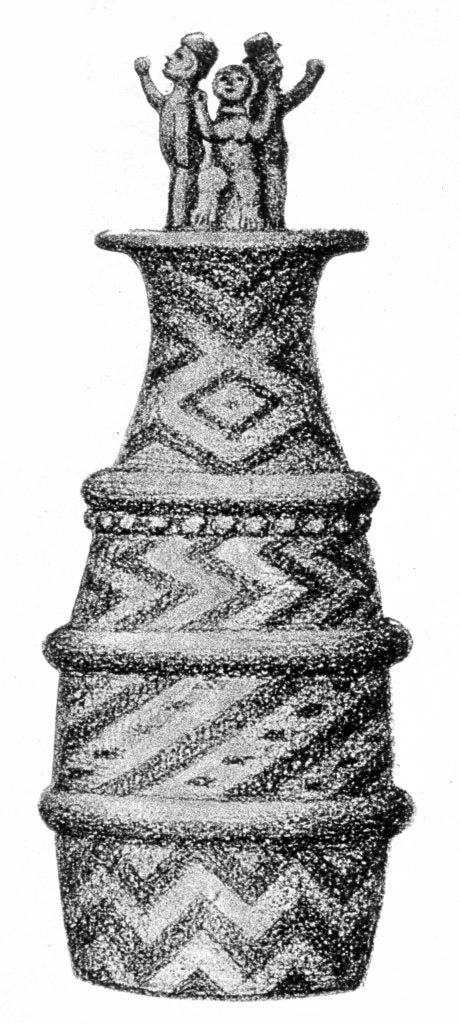

Both the Kongo-Yombe and Kongo-Boma often marked graves of the wealthy and renowned with a terracotta funerary vessel known as a diboondo, made by male artists (Fig. 455). These hollow columns, divided into patterned registers, often included openings on their sides that indicated they served no practical purpose, yet these were references to the void of death and often took the lozenge form of the Kongo cosmogram. Small free-standing or relief figures suggest the presence of mourners or the deceased, depending on their pose, further ornamented these ribbed grave markers, which stand between 12 and 23 inches tall.

As the second decade of the 20th century approached, Kongo trendsetters began to erect grave monuments in the form of Western storied buildings or boats (Fig. 456), and by 1920 the cement that colonialists were using to construct their own tropical houses was also co-opted by Kongo grave artists, who constructed both simple cement tombs as well as elaborate cement structures that could include figures, houses, and other imagery (Fig. 457).

As the century wore on, planes and other motifs appeared, alongside simpler graves faced with reflective white ceramic tiles, their character recalling the white porcelain plates and bowls of earlier graves.

Additional Readings

Allison, Phillip. African Stone Sculpture. London: Lund Humphries, 1986.

Bockie, Simon. Death and the Invisible Powers: The World of Kongo Belief. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Cooksey, Susan, ed. Kongo across the Waters. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2013.

Cornet, Joseph. Art of Africa: treasures from the Congo. London: Phaidon, 1971.

Fromont, Cécile. The Art of Conversion: Christian visual culture in the Kingdom of Kongo. Chapel Hill, NC: published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, by the University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2014.

Jacobson-Widding, Anita. “Funerals in the Lower Congo.” In S. Cederroth, C. Corlin and J. Lindström, eds. On the meaning of death: essays on mortuary rituals and eschatological beliefs, pp. 141-145. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, 1988.

Lagamma, Alisa, et. al. Kongo: Power and Majesty. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.

Scheinberg, Alfred L. “Stone Ntadi sculpture of Bas-Zaire.” African Arts 15 (1, 1981): 76-77.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and the African Americas. New York: Museum for African Art/Prestel, 1993.

Thompson, Robert Farris. “Kongo Influences on African-American Artistic Culture.” In Joseph E. Holloway, ed. Africanisms in American Culture, pp. 148-184. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1990.

Thompson, Robert Farris and Joseph Cornet. The Four Moments of the Sun. Washington, DC: The National Gallery, 1981.