Chapter 4: The Impact of Religion and Hierarchy on African Art

Chapter 4.3 Islam and Art

Islam arose in the 7th century in what is now Saudi Arabia, the result of the monotheistic teachings of the Prophet Muhammed. It quickly spread across the Red Sea to North Africa, where it was already established later in that same century in Egypt, reaching the westernmost regions in the 8th-12th centuries. It rapidly spread southward in East Africa, displacing Christianity in the Sudan’s Nubian states, and attempting unsuccessfully to do so in Ethiopia. In West Africa, its expansion was linked to traveling merchants from North Africa plying the trans-Saharan trade, Islam becoming the dominant religion from the 8th to 15th centuries across much of the Western Sudan–at least in its cities and royal courts. It now prevails in much of the continent

While the Koran–like the Torah and the Bible–condemns idolatry, it does not explicitly forbid the creation of figurative art. There are, however, numerous references in the Hadith, or the collection of statements by the Prophet Muhammed, that proscribe images of Allah, the Prophet Muhammed, and other prophets. Over time, this has generally meant that figurative art itself has been banned by many Muslim societies. Although Turkish, Persian, and Mughal Indians, in particular, have historically produced paintings of human beings, these were uncommon in Africa.

In Senegal, however, popular urban paintings often depict the local Sufi Muslim saint, Amadou Bamba Mbacke (1853-1927). Known as Bamba, he founded the Mourides Brotherhood, which supported equality, peace, and work in an atmosphere of fraternity; Sufi practices emphasize mysticism, spiritual discipline, and meditation. Initially arrested and exiled by the French, they later awarded him the Legion of Honor. Stories about his miraculous works and piety still inspire painters of both murals (Fig. 635)

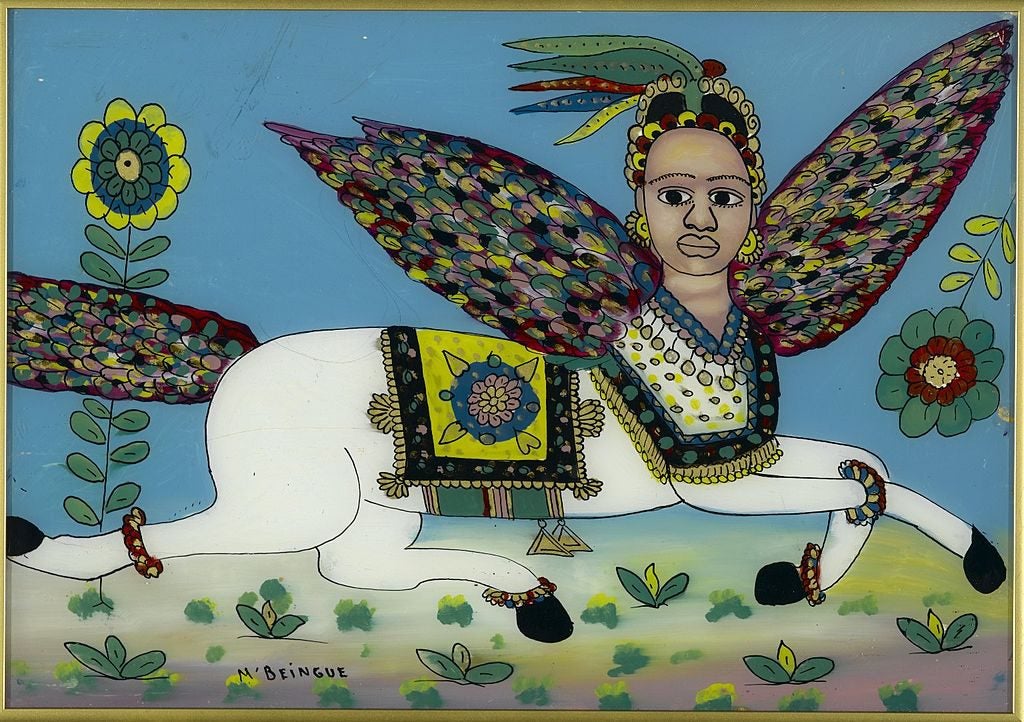

and glass panels; his Senegalese followers today number over three million–more than a third of the country. Popular painters in Senegal, as well as other parts of West Africa, frequently create images of Al-Buraq, the mythical winged white steed that carried the Prophet Muhammed from Mecca to Jerusalem and the heavens and back again (Fig. 636).

Beginning in the 20th century, Senegal and many other predominantly Muslim countries developed art schools where figurative art was taught and spread; urban and academically-trained photographers also produce many figurative images. Nonetheless, the arts of African Muslim regions has traditionally

é

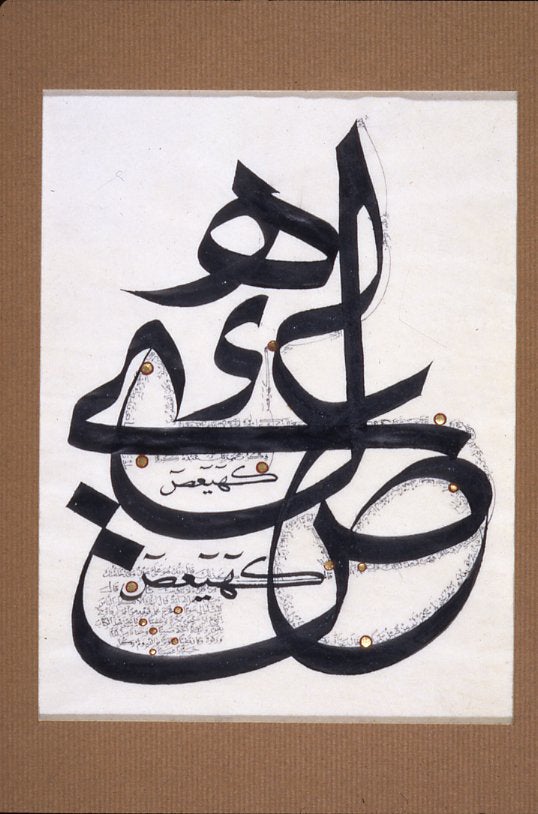

abjured figurative art in favor of architecture and two-dimensional works that stress calligraphy, pattern, and geometry. Even some academic art movements, such as the Khartoum School in Sudan (Fig. 637), have stressed creative ways to employ calligraphic references in non-objective paintings. Calligraphy (“beautiful writing,” from the Greek) has long been a critical art form for Muslims throughout the world. Being literate is an essential part of becoming a scholar, and prayers remain in Arabic no matter where the Muslims concerned are based.

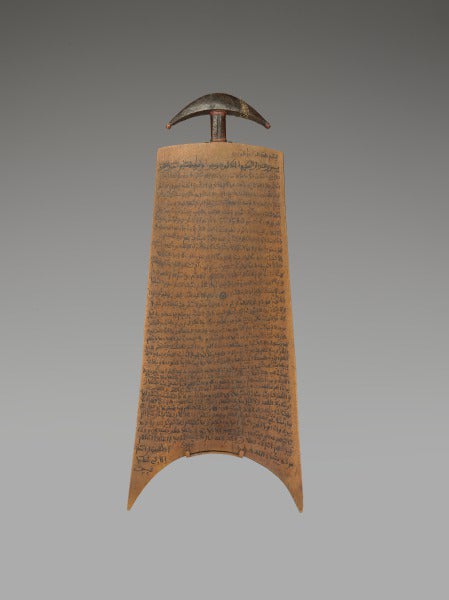

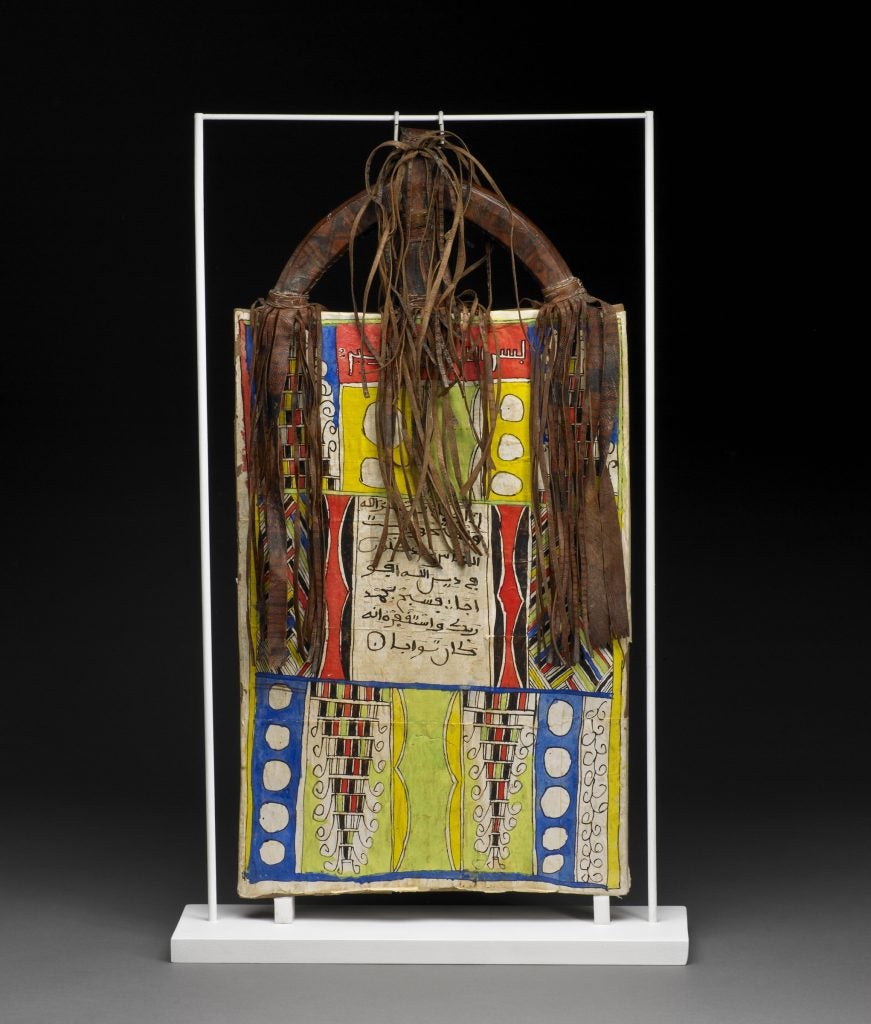

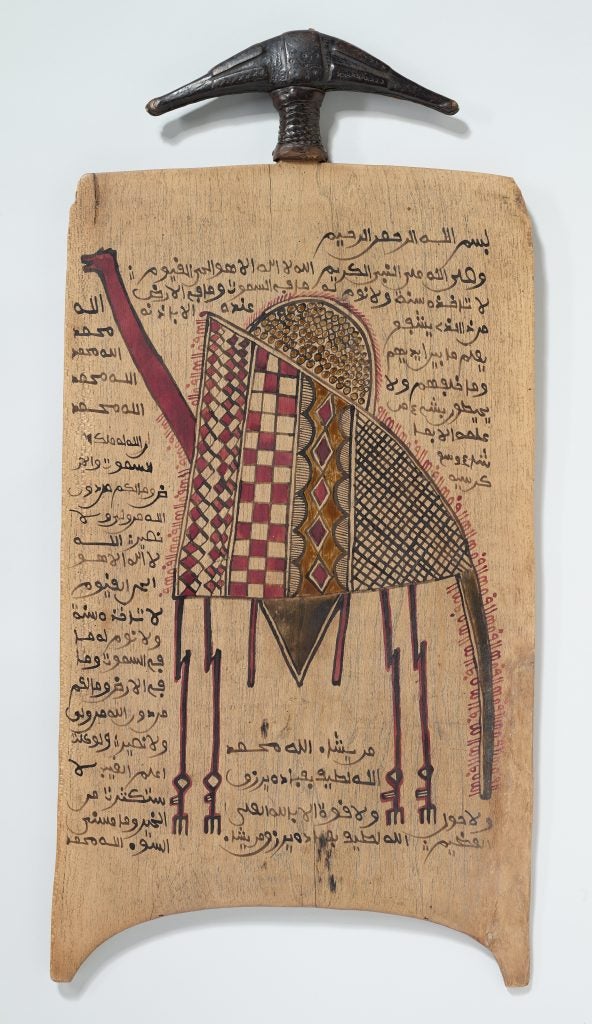

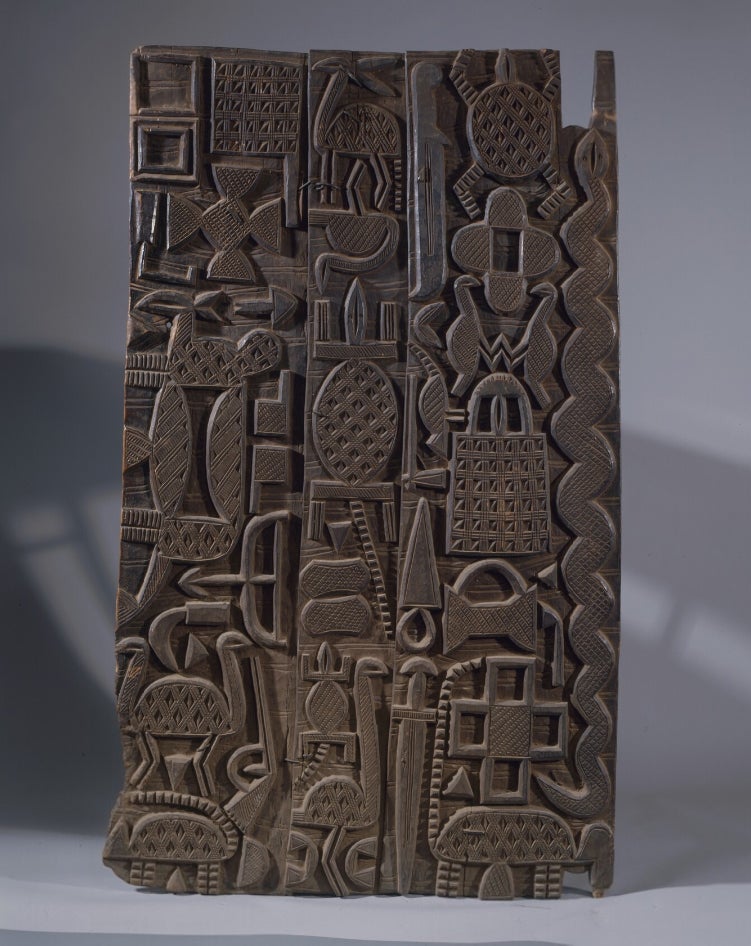

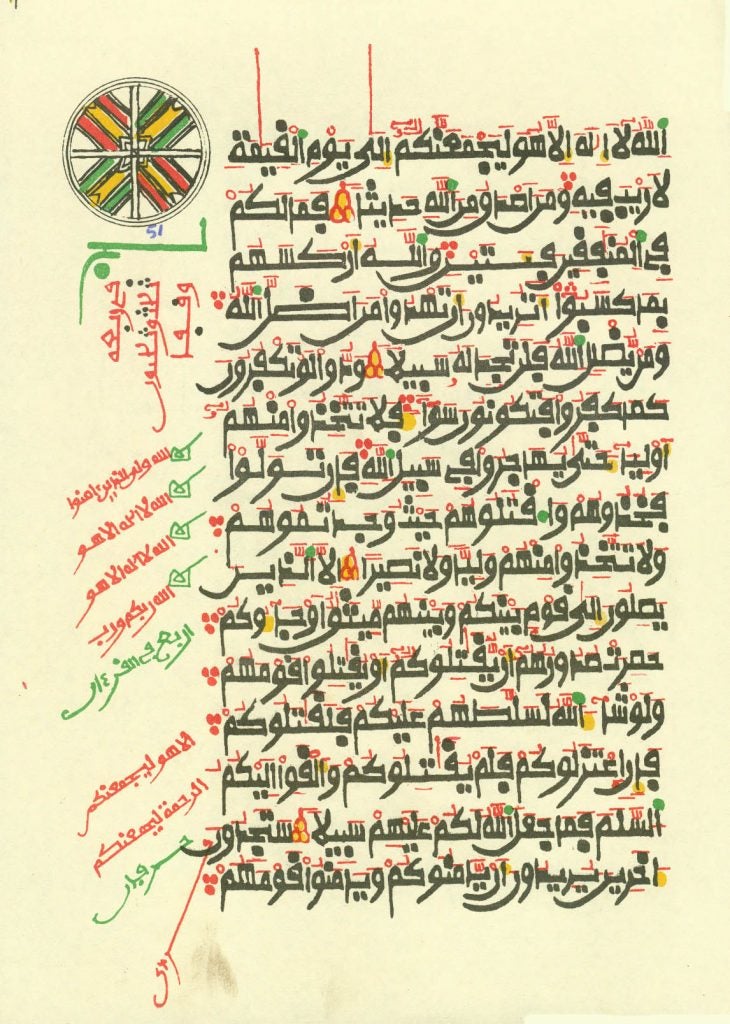

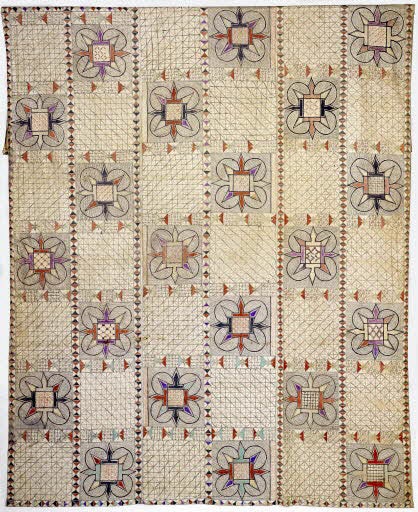

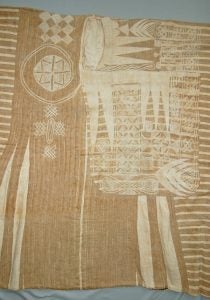

In Africa, Muslim children often attend Koranic schools, frequently in addition to other kinds of Western education. They initially learn to recite prayers and then to write them, often in vegetable-based ink that can be washed off their wooden Koranic slates at the end of the school day, making them fresh for further use (Fig. 638). In the hands of mallams or marabouts (the English and French terms, respectively), experts in the use of prayers as medicines or amulets, prayers written on slates in vegetable ink are rinsed off and the water collected for patients to drink. In Nigeria and some other West African countries, some Koranic slates by those who have completed their studies become advertisements for the calligraphic skills of the teacher who created them (Figs. 639 and 640), the slate itself becoming a motif visible in architecture, textiles, and other mediums as a reminder of the piety of maker and user (Figs. 641, 642, 643).

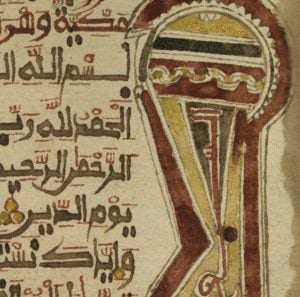

As Muslim students’ scholarship progresses, they learn to recite the entire Koran by heart, and those who wish to become teachers perfect both their calligraphy and the kinds of geometric motifs (Fig. 644) that form a part of the marginalia of manuscripts, for a “graduation” project for advanced students is a handwritten and decorated copy of the Koran (Fig. 645). These are usually loose sheets kept between two covers, the whole protected by a leather bag. Old centers of Islamic learning, such as the mosque-oriented medieval universities at

Timbuktu, Mali, had libraries filled not only with Korans and Koranic commentaries, but hand-copied books that were treatises on science, medicine, geography, and mathematics.

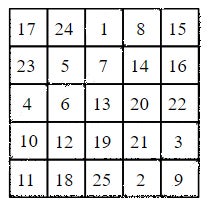

Some Muslim scholars pursue esoteric studies that seek to extract particular medicinal forms of protection from the Koran and the 99 names of God. These date back to early times and come from a common pool shared by Jewish kabbalists and Ethiopian Coptic debtera, and employ a geometric convention known as a magic square inscribed with numbers that add up to the same sum whether examined vertically, horizontally, or diagonally (Fig. 646). Even if the maker is not literate nor mathematically-versed, imitation of the square and associated writing are considered to be efficacious.

By invoking God, using sacred geometry, and employing written prayer, talismans’ configurations vary according to situation–protection against enemies? illness? hunger? They are inscribed, folded, and sewn into leather packets to be worn as amulets (Fig. 647). While such amulets are frequently worn by children and adults alike, they can also hang around the necks of horses, valuable animals whose welfare directly affects their owners (Fig. 648). Prayers and magic squares can also be written on fans (Fig. 649), cloths, or other items that might afford protection. Even non-Muslims, such as the Asante, might purchase and wear these amulets or talismanic items (Fig. 650)–not because they believed in Islam, but because they saw writing as a magic element.

Because the power of the written word was believed to be so compelling, it appears that some of the curvilinear patterns seen in some West African men’s embroidery and even in certain architectural reliefs, particularly around doors, may derive from Arabic letters, even though they are illegible and no longer considered protective devices. Just as some illiterate mallams might “write” prayers in an unreadable script to create amulets, it seems that masons and embroiderers similarly attempted to protect the body or the entrance to homes, even though

this impetus is no longer remembered.

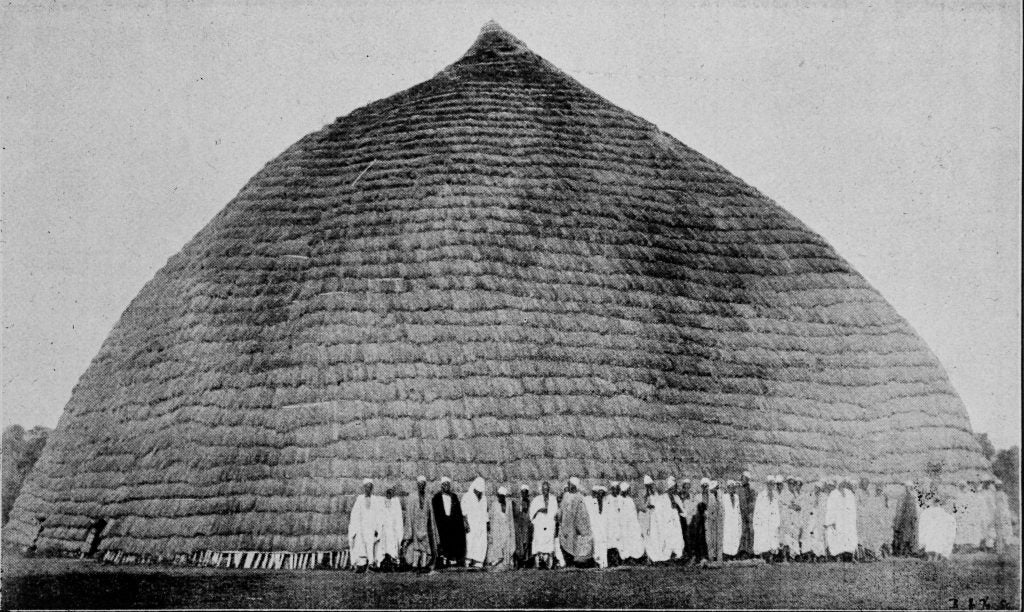

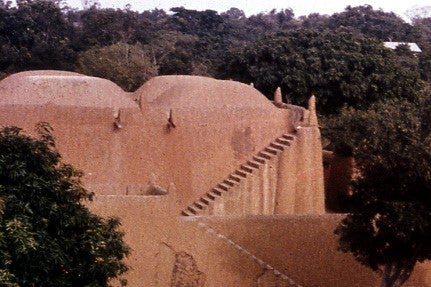

Hausa and Nupe embroidery, in particular, both include a motif which is prominent on both the front and back of men’s gowns: the square within a circle (Fig. 651 at left). This geometric form is one that not only shows up in amulets, but it also became the basis for numerous 18th and 19th-century Fulani mosques in Guinea. Initially, Fulani mosques in the Futa Djalon region were modeled after the thatched round earthen houses of the settled Fulani, which in turn mimicked the temporary fiber structures of nomadic cattle-herding Fulani. These round structures were atypical of mosques worldwide–although the only feature a mosque requires is an indication of the direction of Mecca, where congregants face when saying their prayers. This is typically marked by a niche known as the mihrab, which Fulani mosques share.

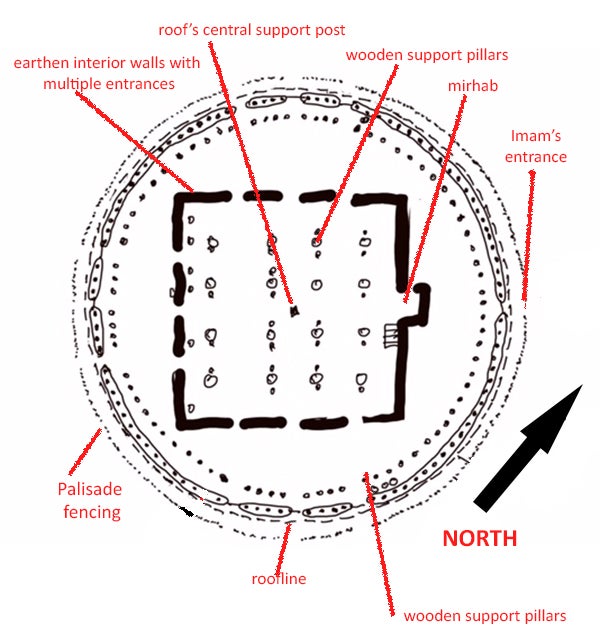

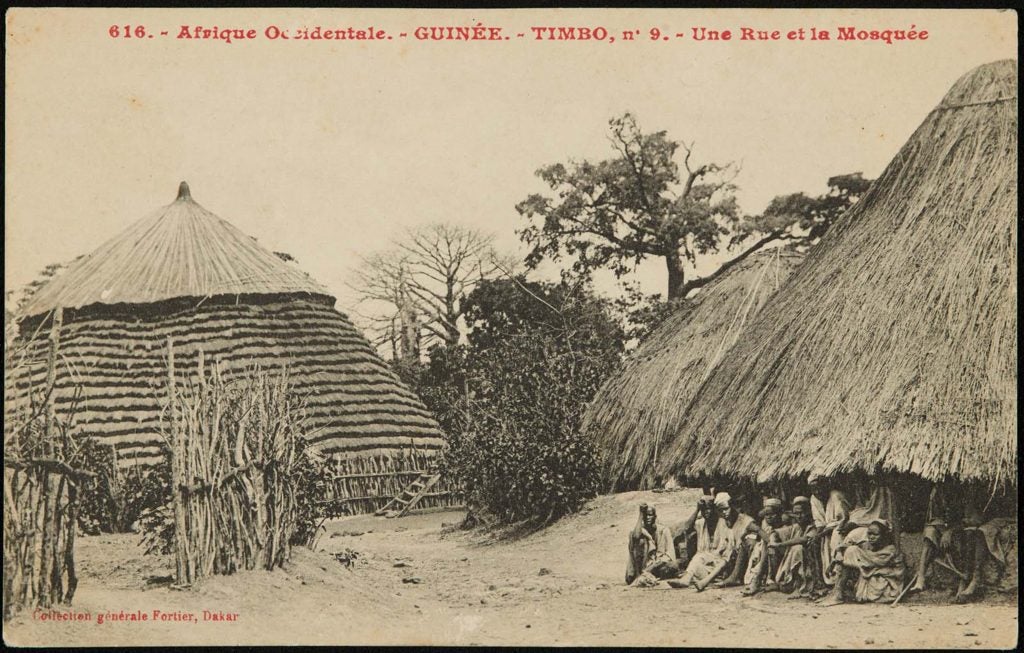

In the mid-19th century, El-Hadj Umar Tall, the Sufi scholar and jihadist leader who created the Toucouleur Empire, designed a mosque in Dinguiraye (Fig. 651), conceiving of it as a magic square in a talismanic drawing. While it was rebuilt after fires in both 1862 and 1904, it is presumed to have kept to the same plan when reconstructed. Its step-thatched roof descended nearly to the ground, surrounded by a circular palisade–both features that emphasized its similarities to nomadic dwellings–with these two concentric circles hiding the square earthen building within (Fig. 652).

Many mosques in the region adopted this form of the circled square, such as the main mosque at Timbo, the capital of the Fulani state of Futa Djalon in the 18th and 19th centuries (Fig. 654). The town marks one of the major dispersions of Islam in West Africa, and is still an important religious center. Begun in about 1727, its original earthen and thatch mosque consisted of multiple round buildings whose stepped thatch roofs and earthen walls were similar to those of the homes of the region’s settled Fulani. The earth and thatch materials of the later structure at Timbo were constantly renewed until 1949, when stone walls replaced earth. The roof kept its shape but was tiled until 1978, when sheet metal replaced it. In 2016, the venerable building itself was replaced by a mosque whose form imitates those of the Middle East and was apparently financed by the Nigerian Embassy in Guinea. Similar progressions have marked other large regional mosques, such as those at Kébaly, Labé, Lélouma, and elsewhere–to the degree that few of the older mosques now survive outside those in villages. Even the Dinguiraye mosque has been demolished. Although the current building (Fig. 655) retains a round form (unlike other Guinea examples), it bears no real resemblance to the original with its two slender minarets, glass windows, and arched portico. The square interior–meant to reference the Ka’aba at Mecca–has vanished.

That square within a circle that appears so prominently on Hausa and Nupe embroidered robes may ultimately tie the motif back to Guinea and the earlier circled square mosques. Despite the distance between Nigeria and Guinea, the late 18th/early 19th century saw Fulani scholars from Guinea take over the leadership of both Nupe and Hausa kingdoms in a series of coups and palace machinations (see below).

African mosques do not have to be enclosed structures. Many workplaces, for example, include dedicated spaces delineated by cement curbs (Fig. 656), with a notch or bump-out serving as their mirhab, the required indicator of the direction of Mecca.

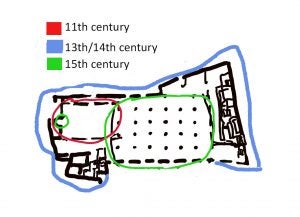

African mosques can vary considerably in their forms, and have done so in the past as well. Some continue their former appearance, while others have adopted foreign forms or struck out in new directions. A now-abandoned Swahili structure, the Kilwa mosque at Tanzania’s off-shore island of Kilwa Kisiwani is a fairly rare example of a sub-Saharan precolonial stone building, and the oldest extant mosque in East Africa (Fig. 657). From the 13th-16th century, this small island was a center of Indian Ocean trade, its wealthy merchants dealing in precious metals, jewels, scent, ceramics from Persia,

China, and the Middle East, ivory and slaves. Made from fossilized coral and originally plastered, the mosque went through several phases of construction (Fig. 658) for expansion. Unlike many mosques, it has no courtyard; the building was meant to accommodate all worshippers, and did so through the use of true arches

and vaults that allowed for fairly large open spaces, albeit with pillars (Figs. 659 and 660). The original mosque, built in the 11th century, was fairly small, but the vaulted portion and other additions were made in the 14th century under the rule of a wealthy sultan, including East Africa’s first true dome that retained its preeminence in size for centuries. Partial collapse of sections of the addition led to its reconstruction in the 15th century, which made it the largest mosque in East Africa; minor additions occurred in the 18th century. Ablutions (wudu)–the sacred cleansing of hands, feet, forearms, head, mouth, ears and nose–often require fountains (or today, taps), and at Kilwa water storage tanks supplied the ablutions areas, with rough stone flooring allowing the feet to be pumiced. In the 19th century, the island was essentially abandoned due to trade shifts, but its mosque and elaborate palace fortress have become UNESCO World Heritage sites, and further sites are being excavated.

Although earth was the favored mosque building material throughout much of West Africa, resulting in structures that appear to grow from the

surrounding earth and have a commanding sculptural presence (Fig. 661), many of these structures have since been replaced by stone or concrete. Some have forms inspired by foreign models. A number of mosques in coastal southwest Nigeria and the Republic of Benin were built in the late 19th/early 20th century by African returnees from Brazil. Born in these regions, they were transported by the slave trade and some left the Americas for Africa after Brazil finally ended slavery and manumitted all laborers. A good number of the returnees were trained builders, masons, and carpenters, and built plastered stone homes in the Brazilian mode of two or more stories in Lagos, Porto Novo, and other coastal cities. Some were Muslims, and participated in the creation of mosques that followed the pattern of Brazilian Baroque churches (Fig. 662), which they had also built: two towers–now for the call to prayer rather than bells; a basilica floorplan with a mihrab where the altar would have been, a central peaked roof usually decorated with curving roofline volute, pilasters and engaged columns, plasterwork relief decoration (Fig. 663), and, frequently, the use of pastel colors.

International travel and other considerations have also resulted in mosques based on foreign models, general or specific. Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia (originally built as a Byzantine church) has served as the prototype for at least two mosques. One, the central mosque of the Nigerian city of Ilorin (Fig. 664), is built on the historic site of the city’s first mosque, built in the early 18th century. It has had its current form since the late 20th century, with its formerly bright blue domes changed to gold in a 2009 refurbishment which saw the addition of a portico and additional peripheral domes. A second, more recent reworking of the Hagia Sophia was constructed in Accra as Ghana’s National Mosque (Fig. 665), and was built by the Turkish

government. Other historic mosques in Egypt, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere have also served as models for more recent structures in Africa.

Ablutions and Mats

A mosque can be created merely by tracing a cement outline on the ground with an indication of Mecca’s direction. Two other features necessary for prayer are associated with cleanliness: water for ablutions and mats for the standing, kneeling, prostration, and seating prayer postures. While these don’t always have aesthetic value (some are public taps or manufactured goods made from plastic), they certainly can have. Nigeria’s Nupe brassworkers, for example, have made repoussé containers meant to be used when cleansing oneself for prayer (Fig. 666). Today these are often replaced–not just by the Nupe but in many parts of West Africa–by a plastic teapot that performs the same function more inexpensively (Fig. 667). While mats are used both domestically by Muslims and non-Muslims alike, commercial prayer mats or rugs may be solely geometric (Fig. 668) or include images of Mecca or mosques. Traditionally-made prayer mats often can be differentiated from household examples only through their smaller size, for they are meant to be rolled up and carried to the mosque or used for prayer at home (Fig. 668). Occasionally, prayers or pseudo-Arabic motifs may be woven into their surface (Fig. 669).

Further Reading

Adams, Sarah and Christine Mullen Kreamer. Inscribing meaning: writing and graphic systems in African art. Milan: 5 Continents, 2007.

Bourdier, Jean-Paul. “The rural mosques of Futa Toro.” African Arts 26 (3, 1993): 32-45; 86.

Bravmann, René A. African Islam. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press; London: Ethnographica, 1983.

Cantone, Cleo. Making and Remaking Mosques in Senegal. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Chittick, Neville. Kilwa: An Islamic Trading City on the East African Coast. Nairobi: British Institute in Eastern Africa, 1974.

Dadi, Iftikhar. “Ibrahim El-Salahi and calligraphic modernism in a comparative perspective.” In Ibrahim El-Salahi: a visionary modernist, pp. 41-53. Long Island City, NY: Museum for African Art, 2012.

Garlake, Peter S. The Early Islamic Architecture of the East African Coast. London: Oxford University Press, 1966.

Hallen, Barry and Carla de Benedetti. “Afro-Brazilian mosques in West Africa.” Mimar: architecture in development no. 29 (September, 1988): 16-23.

Hassan, Salah M. “When identity becomes ‘form’: calligraphic abstraction and Sudanese modernism.” In Okwui Enwezor, ed. Postwar: art between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945-1965, pp. 220-225. Munich/New York: Haus der Kunst/Prestel, 2016.

Heathcote, David. The Arts of the Hausa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977.

Heathcote, David. “Hausa Embroidered Dress.” African Arts 5 (2, 1972): 12-19; 82; 84.

Mark, Peter, “Hyacinthe Hecquard’s Drawings and Watercolors from Grand Bassam, the Futa Jallon, and the Casamance: A Source for Mid-Nineteenth Century West African History.” Paideuma 36 (1990): 173-184.

Meier, Prita. Swahili port cities: the architecture of elsewhere. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2016.

Morris, James and Suzanne Preston Blier. Butabu: Adobe Buildings of West Africa. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004.

Owusu-Ansah, David. Islamic talismanic tradition in nineteenth-century Asante. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1991.

Prussin, Labelle. “Architectural facets of Islam in the Futa-Djallon.” In Karin Adahl and Berit Sahlstrom, eds. Islamic art and culture in sub-Saharan Africa, pp. 21-56. Uppsala: Almqvist och Wiksell, 1995.

Prussin, Labelle. Hatumere: Islamic Design in West Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1986.

Roberts, Allen F. and Mary Nooter Roberts. A saint in the city: Sufi arts of urban Senegal. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 2006.

Rubin, Arnold. “Questions: Some Hausa Calligraphic Charms.” African Arts 17 (2, 1984): 67-70; 91-92.

Zaria Friday Mosque (Masallaci Juma’a Zaria), Nigeria

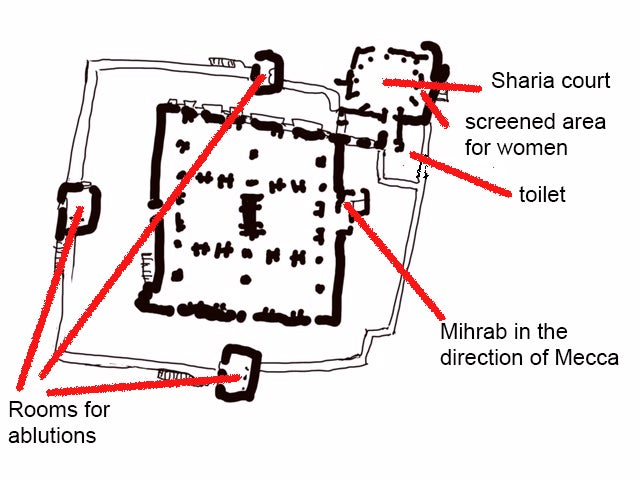

In the 1830s or early 1840s, the Hausa architect Mallam (teacher/master) Muhammed Mikaila Dugura (known as Mallam Mikaia or Babban Gwani) was commissioned to build a new mosque in Zaria City, capital of one of the Hausa emirates (Fig. 670). A British traveler in the 1820s described an 18th-century earthen mosque in central Zaria as having a minaret for the calls to prayer that was 40 or 50 feet high, but the new mosque was to take its place. The idea for the mosque apparently came not from Emir Abdukarim of Zaria, who was installed in 1834 or 1835, but from the Sultan of Sokoto, Muhammed Bello (reigned 1817-1837). The Sultan–the overlord of the entire caliphate–and the Emir of Zaria, like all other emirs of Hausa kingdoms, were not Hausa themselves, but Fulani. Although most had been born, raised, and educated (for the majority were Islamic scholars) in the region, their forebears came from Futa Toro and Futa Djallon in Guinea. They had trickled into the Hausa states since the previous century, accompanied by their non-Muslim, cattle herding brethren.

In 1804, the Sultan’s father, Usman dan Fodio, precipitated a jihad that swept through the area, displacing and supplanting the Hausa monarchs. Although these rulers had been Muslim since the 15th century–and had been in touch with Muslims for at least two centuries before that, the Fulani had found their practice of Islam lax. They also resented Hausa tolerance for non-believers in both rural areas and in the cities. These were two of the main factors that prompted the jihad. After their religious reformation was established, the Fulani rebuilt urban centers damaged after the wars. Among their new constructions were mosques and homes for the new nobility, examples of the former found in Sokoto, Zaria, and elsewhere.

Knowledge of Hausa urban architectural history in centuries past is limited. Written descriptions from the early 19th century refer to buildings owned or commissioned by Fulani aristocrats, though created by Hausa builders, in a style that still survives in Northern Nigeria and Niger. An 1824 description of a nobleman’s walled home speaks to the travelers waiting for their host in “the porch of a square tower,” the entry portal, “in which some of the slaves or body-guard lounge during the day, and sleep at night.” A description of a Zaria compound in 1826 referred to a walled surround and a mixture of round, ostrich shell-topped thatched structures and other rectangular buildings with flat roofs, a pattern that still exists although the ostrich eggs are now rarely seen. However, the Sokoto nobleman’s house described in the same account had distinctive status features that can also still be found today: earthen, the multi-storied structure had a domed roof supported by “arches.” Neither these arches nor the domes share the construction methods of stonework. Instead, bundles of saplings are secured in arcing positions that overlap and reinforce one another, then mud is packed around to envelop them, the whole then smoothed into an apparent arch (Figs. 671 and 672). The areas spanned are limited by the lengths of the type of wood used; a room’s dome is supported by a series of arches meeting at the center, while larger spaces are spanned in a modular fashion with a series of domed units.

In 1824, the caliphate’s Sokoto capital was the site of a third major rectangular mosque’s construction, paid for by the Sultan’s vizier. Its interior included both a small room dedicated to ablutions, and an area for the sole use of the Sultan. A British visitor observed:

“The roof of the mosque was perfectly flat, and formed of joists laid from wall to wall, the interstices being filled up with slender spars placed obliquely from joist to joist, and the whole covered outside with a thick stratum of indurated clay. The roof rested on arches, which were supported by seven rows of pillars, seven in each row. The pillars were of wood, plastered over with clay, and highly ornamented. . . Some workmen were employed in ornamenting the pillars, others in completing the roof; and all appeared particularly busy.”

The mosque’s architect was from Zaria, and may or may not have been Mallam Mikaila himself; that would explain why the Sultan was familiar with his work and sent him south to construct a mosque in his home town. The Sokoto mosque’s designer told the British traveler that his “his father having been in Egypt, had there acquired a smattering of Moorish architecture, and had left him at his death all his papers, from which he derived his only architectural knowledge.” He requested a Gunter’s scale, the precursor to the slide rule, which could calculate logarithms and trigonometric equations, which the traveler sent him later.

Nearly a decade later, Mallam Mikaila used six domes to create a sizable interior for the main Zaria mosque, referred to as the Friday mosque because the sermons delivered on the Friday holy day drew more than the usual number of male attendees. While the exterior walls were treated plainly, the interior’s 21 piers included relief geometric designs of the type the Sokoto mosque (which had collapsed by 1853) had (Fig. 673), an ornamental feature shared by aristocratic homes. The 1826 traveler’s account mentioned the latter, saying: “The clay serves to keep the white ants [termites] from destroying the wood; they are ornamented in their fashion while the clay is wet, an operation performed with the fingers and a small square stick.” Instead of the pillar-supported arches of Sokoto, Mikaila’s doubled arches on doubled piers at Zaria created both an elegant appearance and greater structural stability (Fig. 671 and 672), though, as occurs in most larger earthen buildings, they prevented open interiors. It contained both a prayer hall and a Sharia court with a screened section for women; the emir entered the mosque through the court (Fig. 674). The finished whitewashed surface originally glittered with the addition of mica, a treatment not accorded normal architecture. The designer “signed” his creation by leaving his handprint by the upper part of an arch

Mallam Mikaila was himself Hausa, both the son of a master builder and the founder of a dynasty–one of his descendants is always appointed Zaria’s chief mason. He is remembered for having built extant sections of the Emir of Kano’s palace, as well as a mosque in Birnin Gwani, part of the Emir of Bauchi’s palace, and numerous other structures. However, was his arch and imitative dome structure already a Hausa invention that the Fulani aristocrats simply adopted? Or did the Fulani suggest stylistic and structural changes that Mallam Mikaila adapted and perfected? Certainly, the thatched, square-within-a-circle structure that made Fulani mosques in Guinea so distinctive (see above) were not reestablished in Hausaland. However, the absence of Guinea minarets may have led to the abandonment of those structures at Zaria, where they were already in use on earlier Hausa mosques. Architectural historians disagree regarding Hausa traditions, Mikaila’s inventiveness, and Fulani influence. Concerning the latter, the pastoral Fulani “tents” consist of a sapling armature lashed into a hemispheric form, then covered with thatch, matting, or other fiber. In some respects, the Zaria dome and other Fulani-Hausa examples have a similar beginning. The armature is then embedded in clay, affording more permanence to a familiar form.

With regular maintenance, the Zaria Friday Mosque survived to the 20th century, though damage to some sections was significant, and the Sharia Court was lost. By the 1970s, it was decided it should be preserved not through restoration, but by encasing it inside another structure to protect it from the elements. A new Friday mosque was constructed on site, the remnants of the old building hidden from public view (Fig. 675).

Further Reading

Aradeon, Susan B. “Maximizing Mud: Lofty Reinforced-Mud Domes Built with the Assistance of Supernatural Powers in Hausaland.” Paideuma 37 (1991): 205-221.

Clapperton, Hugh and Richard Lander. Journal of a Second Expedition Into the Interior of Africa; to which is Added the Journal of Richard Lander from Kano to the Sea-Coast. London: Murray, 1829.

Denham, F. R. S., Hugh Clapperton and Doctor Oudney. Narrative of Travels and Discoveries in Northern and Central Africa, In the Years 1822, 1823, and 1824, 3rd ed., vol. 2. London: Murray, 1928.

Dmochowski, Z. R. An introduction to Nigerian traditional architecture, Vol. 1: Northern Nigeria. London: Ethnographica, 1990.

Lockhart, James Bruce and Paul Lovejoy, eds. Hugh Clapperton into the Interior of Africa: Records of the Second Expedition, 1825-1827. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill N.V., 2005.

Moughtin, J. C. Hausa Architecture. London: Ethnographica, 1985.

Moughtin, J. C. “Hausa Building Techniques.” In Colin Chant and David Goodman, eds. The Pre-industrial Cities and Technology Reader, pp. 235-244. Abingdon, UK: The Open University, 1999.

Prussin, Labelle. “Fulani-Hausa Architecture. African Arts 10 (1, 1976): 8-19; 97-98.

Prussin, Labelle. Hatumere: Islamic Design in West Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1986.

Schwerdtfeger, Friedrich W. Hausa Urban Art and its Social Background: External House Decorations in a Northern Nigerian City. Berlin: LIT Verlag Münster, 2007.

The Jenne Main Mosque, Mali

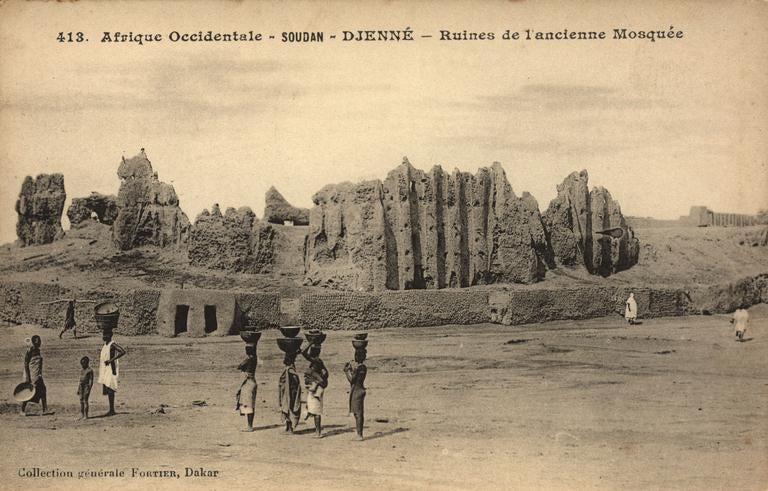

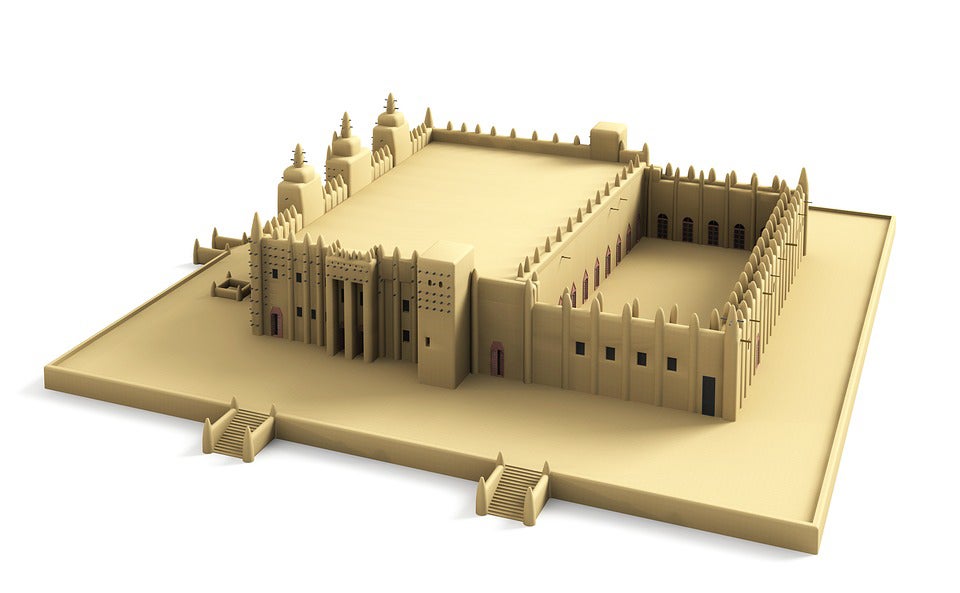

One of West Africa’s best-known mosques is the Friday mosque at Jenne, Mali (Fig. 676), which is the largest earthen building in the world. Although

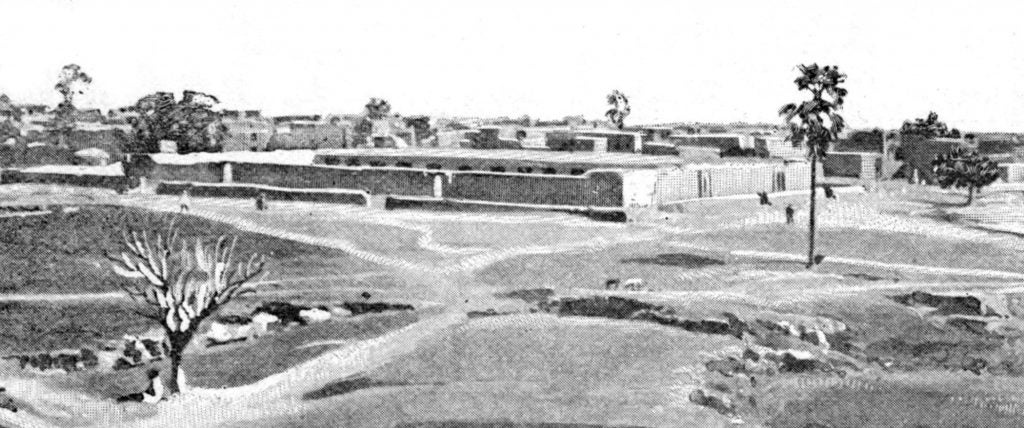

it was built in 1906-1907, it stands in generally the same urban spot where its two predecessors were located since approximately the 13th century, when the city’s ruler first converted and leveled his palace into a mosque. His immediate successors added minarets and surrounded it with a wall, but its precise original appearance is unknown (Fig. 677). In the early 19th century, the Fulani scholar Sekou Amadou grew disgusted at what he felt was the moral laxity of Jenne, a multi-ethnic, cosmopolitan trade city. Like a number of his fellow Fulani, his reforming zeal had a political aspect–he launched a jihad in 1818 which led to his establishment of the Empire of Masina, a state within present-day Mali that stretched from Timbuktu to Ségou, and included Jenne, which attempted several rebellions. In his efforts to subdue those conquered, he ordered Jenne’s mosques closed, but Islam forbade him from actively destroying them. Instead, he stopped up the gutters of the main mosque. During the rainy season, the dammed water ate at its walls and caused the roof to cave in. By 1828, a French visitor noted it was deserted and in ruins, prayers being said in an outer courtyard. Sometime between 1834 and 1836, Sekou Amadou erected a new mosque adjacent to the old one’s ruins (Fig. 678). Bigger than the former building, it was lower and plainer, lacking minarets. By 1861, Jenne became part of the Toucouleur state, and Sekou

Amadou’s empire was destroyed.

By 1893, the French occupied the city. When the French colonialists offered to pay for a new Islamic school and mosque in Jenne, the local authorities decided Sekou Amadou’s mosque should be destroyed in a kind of reclamation of their ownership of the city. Forbidden by Islamic law to do so themselves, they invited the French to raze the site, and had the school built on its land. The mosque rose next to it, where the first mosque had once stood. Towers returned to the new structure, as

did a high ceiling, and a shorter women’s gallery was built, allowing women to worship at the mosque, albeit in a segregated facility.

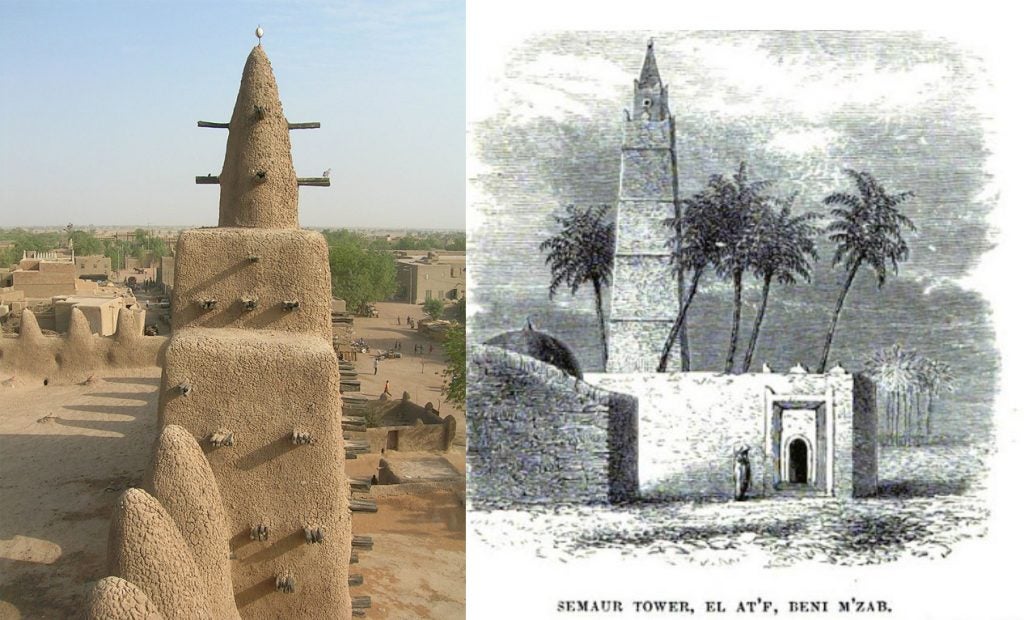

Right: The minaret of a northern Algerian mosque formerly in El-Attaf, also topped by an ostrich egg. Image from H. B. Tristram, The Great Sahara: Wanderings south of the Atlas Mountains. London: Murray, 1860, opp. p. 170. Public domain.

The building complex (Fig. 679) consists of a low wall surrounding two Muslim saints’ tombs, as well as the main structure–a flat-roofed prayer

hall supported by 90 pillars–and an adjacent courtyard (Fig. 680), all elevated on a platform. The exterior entrance facade has three towers, its apparent symmetry incorporating the pleasing irregularities that mark much of traditional African art and architecture. Its wall is not flat, but has shallow projections that mimic the forward thrust of the towers and create changing shadow patterns.

Phallic-like protrusions (sarafar) along the roofline echo the larger examples on the towers; they are topped with ostrich shells, a symbol of fertility. These shells are often described as having protective purposes to ward off the evil eye. It is hard to say how long the association of phallic projection and ostrich shell on mosques has existed, but it is common throughout the Western Sudan, and can also be found in parts of Algeria on both mosques and tombs (Fig. 681).

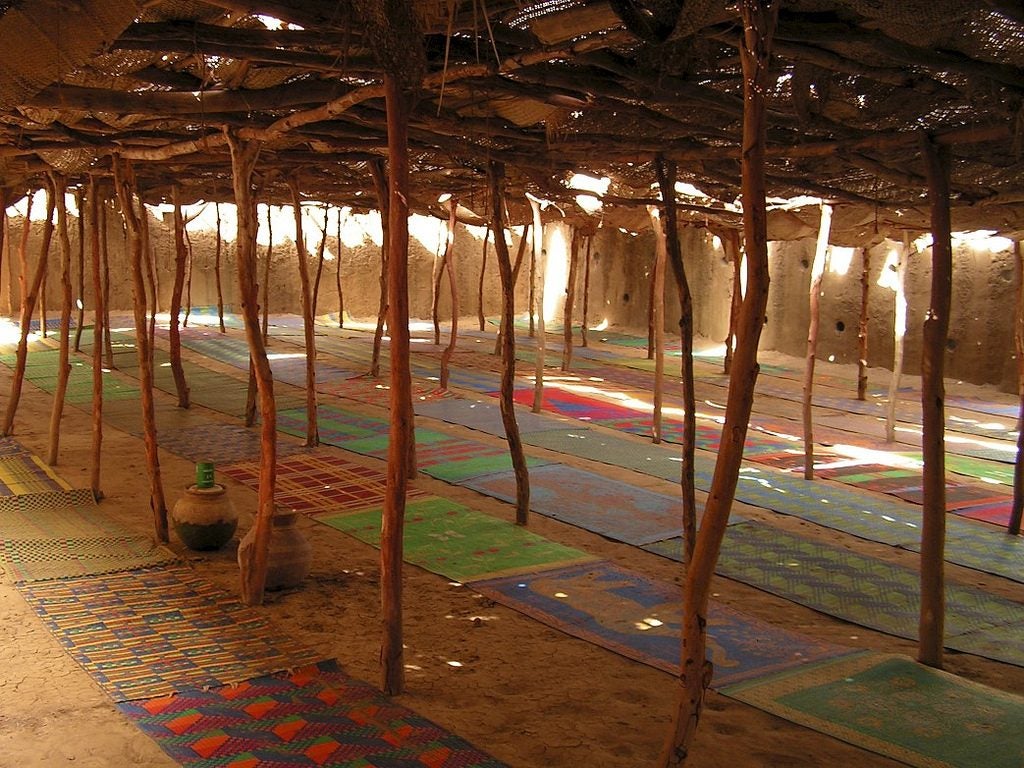

The facade’s towers face east, and each of the three towers has a hollowed niche on the inside that acts as a mirhab, directing the participants to face towards Mecca as they pray. Besides the pillars, the interior is fairly plain, with little natural light (Fig. 682). Each congregation member brings his own mat, and the floor is sandy, the community having rejected external offers of tiling and other materials. The

shaded interior and the cooling insulation provided by the mosque’s thick walls contrast with the heat and sun outdoors. The flat ceiling is punctuated by a series of small lidded ceramic projections (Fig. 683). When hot air rises within the building, the lids can be removed and the air is vented, a further cooling device that also permits additional light to filter into the dim environment.

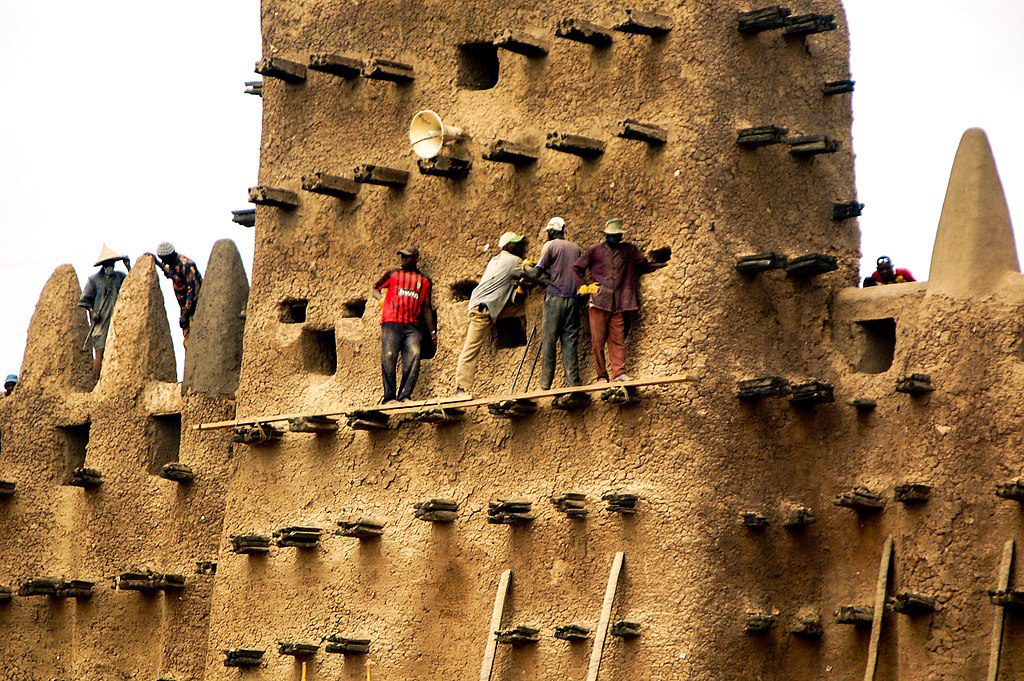

Master mason Ismaila Traoré directed other masons and numerous conscripted laborers in the mosque’s construction. Most of Jenne’s masons belong to the Bozo ethnic group and are part of a hereditary guild. Because many of Jenne’s houses are multi-storied, the skills of trained builders are necessary to avoid collapse; single-story traditional houses in Africa pose less engineering issues, enabling most men to build houses with the help of family and neighbors.

Annually, the mosque is resurfaced during the dry season in a festival atmosphere. This takes place rapidly and involves much of the population: musicians play and sing as small boys bring prepared mud from the riverside, unmarried girls fetch water, masons and their apprentices climb precarious ladders and stand on the mosque’s toron, projecting bundles of sticks that act as a permanent scaffolding (Fig. 684). Two quarters of the town compete to see who can complete the resurfacing of their half of the exterior most rapidly, adding to the frenetic activities (see video below). This was formerly done with a week’s interval in between; since 2005, it is completed in a single day.

The United Nations’ agency UNESCO marked the mosque, archaeological sites at Jenne-Jeno, and an entire old city section of more than 82 acres as a World Heritage site in 1988. Since then UNESCO, the Malian government, and external agencies such as the

Aga Khan Trust for Culture have become increasingly involved with the mosque and efforts to boost tourism. This has included consolidating the two days of resurfacing into one, shifting the date of the resurfacing, investigating potential damage (an Aga Khan Trust action involving the roof that prompted a riot in 2006), and stripping previous layers of exterior mudding, which suspended resurfacing for three years. Tensions and struggles over cultural heritage and Jenne’s “ownership” have proved periodically contentious. However, the mosque’s fame has made it a national emblem, appearing on everything from stamps to

hand-made tourist items (Fig. 685).

The building has generated considerable interest since French colonial days. It has influenced mosque design in Mali itself, including the main mosque at Niono to the south of Jenne, whose facade owes debts to both the Jenne mosque and French colonial architecture (Fig. 686). It was visually transplanted to France itself–albeit in abridged form–in 1930 as a military camp’s mosque for troops from the colonies (Fig. 687).

Initiated by Captain Abdel Kader Madenba and built by Senegalese riflemen, it was made from cement its main space being an open-air courtyard. Its relatively small size, military location, and figurative imagery on courtyard medallions made it unsuitable for contemporary Muslim residents of the town, and it was decommissioned in favor of a new building. Further afield, in South Korea’s vacation destination of Jeju Island, a replica of the Jenne Mosque opened in 2004 as the Museum of African Art (Fig. 688). Though scaled down from the original, it matches its height and is constructed from a recipe that includes clay, as well as concrete and fiberglass. World aesthetic attention and a growing curiosity about eco-friendly building techniques have sent many of Jenne’s masons on international tours. In 2007, six masons traveled from Jenne to Gimhae, South Korea for a “mosque building performance,” a demonstration at the Clayarch Gimhae museum dedicated to adobe/ceramic architectural structures. Additional demonstration trips to the Netherlands, France, and the U.S. followed, spreading awareness concerning techniques and the architectural beauty of Jenne’s mosque and other buildings internationally.

Further Reading

Bourgeois, Jean-Louis. “The History of the Great Mosques of Djenné.” African Arts 20 (3, 1987): 54-63; 90-92.

Dubois, Félix. Timbuctoo: the mysterious. New York: Longmans, 1896.

Joy, Charlotte. Politics of heritage management in Mali: from UNESCO to Djenné. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2012.

LaViolette, Adria Jean. “Masons of Mali: a millennium of design and technology in earthen materials.” In S. Terry Childs, ed. Society, culture, and technology in Africa, pp. 86-97. Philadelphia: MASCA, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1994.

Lorcin, Patricia. The Southern Shores of the Mediterranean and its Networks: Knowledge, Trade, Culture and People. London: Routledge, 2015.

Marchand, Trevor H. J. “The Djenné Mosque World Heritage and Social Renewal in a West African Town.” In Oskar Verkaaik, ed. Religious Architecture: Anthropological

Perspectives, pp. 117-148. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2013.

Marchand, Trevor H. J. The Masons of Djenné. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2009.

Marchand, Trevor H. J. “Negotiating Licence and Limits: Expertise and Innovation in Djenné’s Building Trade.” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 79 (1, 2009): 71-91.

Morris, James and Suzanne Blier. Butabu: Adobe Architecture of West Africa. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004.

Prussin, Labelle. Hatumere: Islamic Design in West Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1986.

Snelder, Raoul. “The Great Mosque at Djenné: its impact today as a model.” Mimar: architecture in development no. 12 (1984): 66-74.

Tristram, H. B. The Great Sahara: Wanderings south of the Atlas Mountains. London: Murray, 1860.