Chapter 4: The Impact of Religion and Hierarchy on African Art

Chapter 4.4 Art in Nomadic Societies

Nomadic and semi-nomadic herders of cattle and/or camels normally have few sculptural traditions, since constant packing and moving provide practical limitations on heavy goods that require transport. They are not without art, however. Sometimes these are confined primarily to body arts, as among the pastoral Fulani (see Chapter 3.2). In other cases, painting rock outcrops that formed part of the natural landscape provided an outlet, as it did for the San or the various successive peoples of the pre-desertified Sahara (see Chapter 3.1 for both). Architecture–usually made in less permanent materials than clay–can be an additional form of artistic expression, especially in semi-nomadic communities where women, the elderly, and young children operate from a fairly permanent base.

Because of desertification and drought, members of some nomadic groups have been forced to settle by

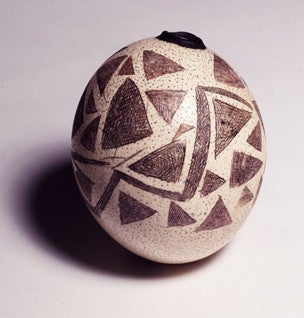

circumstance, rather than through choice. This can have major repercussions on the arts. Some artists may be separated from their standard patrons and forced to seek new markets. Choices in housing types may be changed in urban environments. Some object types become unnecessary to survival. The San, for example, formerly decorated emptied ostrich eggs, filled them with water, plugged them and buried them along their routes as personal reservoirs (Fig. 689). With growing settlement sites, these are unneeded. Even those San who still trek in the desert find plastic containers to be less fragile and hold more liquids.

Political persecution, missionization, and national drives toward education may alter some individuals’ choice of profession and lifestyle, while others are able to retain their traditions because of little interference. Two “ethnicities” with the same ethnic background show the effects of outside impact. Both the Himba and the Herero of Namibia (spilling into Angola and part of Botswana) have a shared language and customs, but their experience of colonialism split them into two groups, one rural, the other town-based, a split that remains visible through their dress and other body arts. The Himba are rural, herding cattle, sheep and goats in a desert environment. Their clothing mostly consists of leather, and their body arts stress a scented red ochre that is used on skin and hair. Female hairstyles distinguish age groups and marital status (Fig. 690). The Herero, on the other hand, were missionized and progressively dispossessed of land and cattle by German settlers in Namibia. After war and decimation by the Germans from 1903-07, they retained European uniform styles for men and Victorian-era full, long skirts for women, though applying their own twists and stylistic shifts to both. These remain dress wear; the women’s headwear consists of cloth stiffened from the inside with newspaper into a shape of two cow horns, a reference to their source of wealth, even though many are town dwellers (Fig. 691).

Further Reading

Beckwith, Carol and Angela Fisher. African Ark: People and Ancient Cultures of Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa. New York: Abrams, 1990.

Cole, Herbert M. “Living art among the Samburu.” In Justine M. Cordwell and Ronald A. Schwarz, eds. The fabrics of culture: the anthropology of clothing and adornment, pp. 87-102. The Hague: Mouton, 1979.

Galichet, Marie-Louise. “Aesthetics and colour among Maasai and Samburu.” Kenya past and present No. 20 (1988): 27-30.

Hendrickson, Hildi. “The ‘long’ dress and the construction of Herero identities in Southern Africa.” Journal of African Studies 53 (2, 1994): 25-54.

Klumpp, Donna and Corinne Kratz. “Aesthetics, expertise, and ethnicity: Okiek and Maasai perspectives on personal ornament.” In Thomas Spear and Richard Waller, eds. Being Maasai: ethnicity and identity in East Africa, pp. 195-221; 303-316. London: James Currey, 1993.

Naughten, Jim. Conflict and Costume: the Herero tribe of Namibia. London: Merrell, 2013.

Prussin, Labelle. African nomadic architecture: space, place, and gender. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Press, 1995.

Sampson, C. Garth. “Ostrich eggs and Bushman survival on the north-east frontier of the Cape Colony, South Africa.” Journal of arid environments 26 (4, 1994): 383-399.

Verswijver, Gustaaf. Omo: people and design. Paris: Édition de La Martinère, 2008.

The Tuareg: From Tent to Cement

The Tuareg are a far-flung Berber group that roam an increasingly large area, as desertification and strife push them into new areas. Once the prime Sahara-crossers, mounted on horse and camel backs, their lifestyle has changed considerably in the past fifty years, forcing many out of the nomadic lifestyle into settlements. Formerly, their casted society was led by the nobility (imajeren), who coupled a warrior ethos with camel-breeding. Their vassals and slaves supplied them with tribute food and labor in exchange for protection, and a separate class of artists (inadan) acted as their mediators and managers, also supplying them with the jewelry, household items and decorations that reinforced their aristocratic status. While none of these elements have completely vanished, Tuareg men with machine guns also patrol in four-wheel-drives, or live settled lives in cement block buildings. Their slaves are—at least officially—liberated, and the inadan, who saw their traditional patrons’ dominance slip away, have gone global. Today they actively create new outlets for their products and often outstrip their former leaders in terms of wealth. The 1950s through the 1970s were a key transitional era, before items regularly made for personal use were abandoned–or persisted and shifted with an expanded international market.

Although some Tuareg have always had residences in towns and cities, especially in Niger and Mali, several severe droughts and other economic hardships drove many more to a sedentary lifestyle. Some Tuareg nomads inhabited fiber structures, but most once lived in a tent, the shelter some Tuareg still use and the norm in the living memory of many others. The word for tent—ehen—is also the word for marriage and womb. A woman’s family gives her this dwelling when she weds, and all its goods belong to her as well. The western Tuareg generally use goat skins (Fig. 692), while those to the east favor matting. The skin versions are a woman’s permanent link to her mother and family, for mothers of the essentially

matrilineal Tuareg begin the preparation of a bride’s tent by cutting off a section of their own. Friends and relations supplement this piece with leather additions, the whole sewn together at a party. Weddings include several tent-related rituals that culminate in the erection of tent poles.

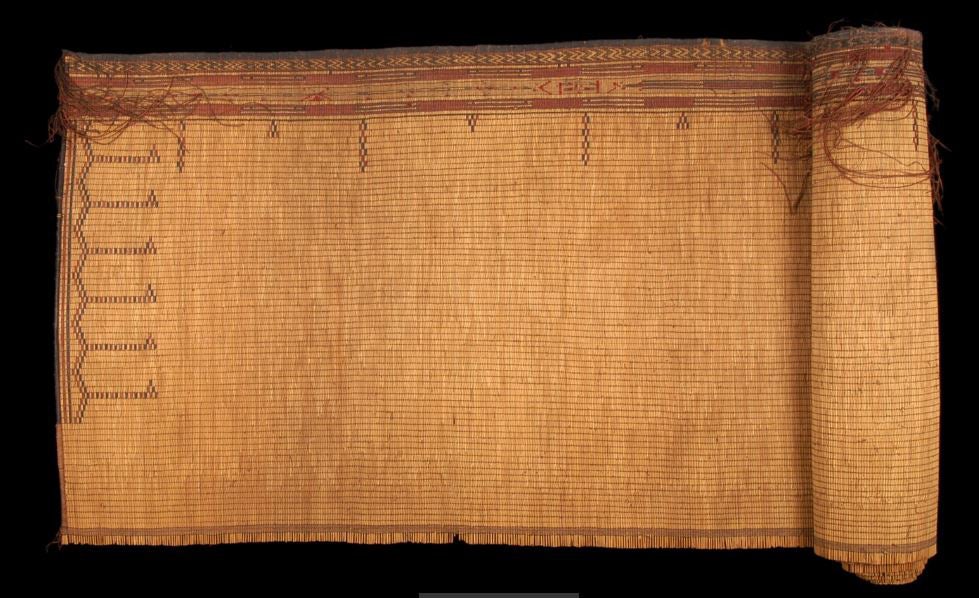

Once the new couple is established, the wife creates an inward-looking environment, transforming the inhospitable desert with their tents. Although tent exteriors are generally plain, the interiors can be a flowerbed of color. While the Tuareg do not weave, they purchase rugs and other textiles from sedentary peoples (Fig. 693), decorating tent interiors with

Berber hangings from Morocco or Fulani hangings from Mali. Women also inject color and pattern into their tents with fringed leather decorative panels (Fig. 694) made by the tinadan, the female members of inadan craftsmen families, as well as utilitarian leather goods.

Tents are synonymous with the ideal of monogamy, and even though some men have multiple wives, no two women’s tents occupy the same compound. The tent is the daily domain of women, children, and elderly men, as most males spend their day outside the domestic sphere. If a couple divorces, the man becomes homeless, at least temporarily. At a woman’s death, her tent is demolished and her matting given away, the space it occupied left delineated for a year. After that, only memories remain.

Skin-spanned tents can be supported by posts and guy-line pegs made from available wood, but wood’s scarcity in the desert region makes that practice risky. Carved posts and pegs used to be the norm, and were carried from camp to camp on pack animals. The southern Tuareg of Mali and Niger made matched sculptural poles (igem) that flanked the tent’s entrance (Fig. 695), although these are uncommon today. Those from Algeria were simpler and decorated with pyro-engraved lines. Elaborately open-worked additional wooden supports (ihel) (Fig. 696) propped up long leather-trimmed leather and reed mats (esaber) that sectioned off the conjugal couple’s bed or edged the tent’s perimeter (Fig. 697).

These mats can easily be rolled out of the way for a breeze, but when down, they act as a windbreak and shield the interior from sand and observers.

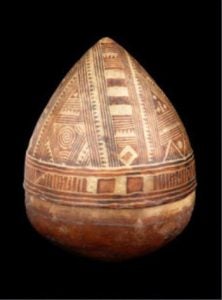

All household items belong to Tuareg woman, and precious objects are stowed away in boxes or kept in leather bags (Fig. 698) that could be protected by a large lock (tanast) (Fig. 699). Not all possessions were so carefully guarded. Some were kept in an acorn-shaped bata lidded box (Fig. 700). Tinadan women

from Niger craft these containers from pieces of animal skin that are soaked until they can be molded over a clay form. The designs are made by rolling wax into threads, applying them to the surface, then dyeing the outside with a red derived from millet stalks. The wax protects the

original color of the leather, leaving a two-tone geometric-patterned surface when it is removed. Although this example was made in the mid-twentieth century, it differs little from those published in 1900. While bata hold often contain jewelry, coins, makeup or pomade, they can also hold granulated incense (tefarchit). More elaborate containers (Fig. 701) can also hold scent, which the Tuareg value highly, whether in the form of perfume, incense or aromatic powders, and are

expected to share it with visitors. Beyond its creation of a pleasant environment, scent is used in curative and diagnostic practices by dispelling evil, harmful spirits and disease, and reinforcing friendship, love and a sense of communion.

Inadan men carve wooden items such as the posts, bed, mortars and bowls for the nobles, and also work metal for jewelry and accessories. An endogamous group, the inadan are analogous in many ways to the Mande nyamakala (see Bamana section of Chapter 3.1), although they compress many of the varied nyamakala groups’ duties into one. Their mastery of mystical powers and satirical song combine to check the nobility’s behavior toward them. In the past, they were indispensable not only for their creativity but for their positions as noblemen’s managers, go-betweens and marriage brokers. Their extroverted behavior is meant to be a strong contrast to the nobles’ reserve, and it is often employed as a diplomatic stratagem.

In the past, nobles had both the resources and the power to commission exquisite metal

objects from the smiths. Silver is still the most common metal of choice, and is associated with the aristocracy and virtue, with brass and copper included in small amounts for color contrast. The silver was melted down rather than mined, much of it formerly from Austrian Maria Teresa thaler coins, which circulated worldwide from their mid-eighteenth century inception through the early1960s, when trade coin minting in other countries finally ceased. Although the Koran itself does not prohibit the use of gold, various Muslim traditions as recorded in the hadith particularly warn men against wearing it, and perhaps reinforced a Tuareg preference for silver. Although uncommon in decades past, inadan smiths now produce some gold jewelry, for it has become fashionable, particularly among urbanized

women who see their Hausa and Malian counterparts favor it. Copper is believed to have healing and protective properties, and was derived from discarded cartridges, while old cans formed the primary source for aluminum and tin. Battery oxide emphasizes designs engraved in metal by blackening the submerged areas.

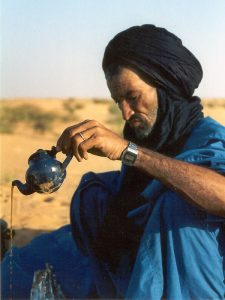

Smiths also produce metal items related to tea drinking, a semi-ritualized Tuareg practice that takes place at least four times a day—once immediately upon rising and after each meal, as well as when guests arrive. Men are the arbiters of its preparation, usually preparing and consuming it outside the tent, while women make and drink it within. The tea itself involves a mixture of strong Chinese gunpowder or green tea, spearmint, and sometimes other spices or flowers, heavily sugared and boiled over a charcoal fire. Its preparation, if not as stylized as that of the Japanese, still involves specific steps meant to achieve not only the perfect taste, but a perfectly foamed glass. The performative aspect is strong, tea being poured and repoured from a height. Three rounds are

expected: the first glass is strong and bitter, the second, somewhat diluted and heavily sugared, and the final is light, sweet and minty or spiced. The length of time necessary for these rounds—their boiling, aerating and drinking—is no hasty affair, and the beauty of the utensils is meant not only to demonstrate status, but to civilize the harsh environment with hospitality and refinement. At an average of 15.24 lbs. of tea a year, the Tuareg outconsume the English nearly three times over, drinking it every three to five hours. The process is so engrained with identity they nickname themselves “the sons of tea” (Ag al-Tay).

Tea accessories are thus amongst the most regularly handled possessions a person owns. While the inadan do not make teapots (albirade)—these these have always been imported or market purchases—they regularly embellish and “Tuaregize” them. On the formerly popular tin Moroccan pots, this often included additions of copper or brass surface motifs, modifications of the handle or spout, replacement of the lid finial, or even the addition of a copper ring base (Fig. 704). By the 1950s, nobles preferred multi-metal contrasts and small sections of patterning. Currently, imported blue enamel Chinese teapots are most common; their color matches that of typical Tuareg robes, which may add to their appeal. Some teapots are carried in specialized leather bags (tekabawt), along with other related supplies. Tea is drunk from small North African glasses (enfenjars) that may be stored in fitted wooden boxes, sometimes leather-covered. In the past, extraordinary metal containers (Fig. 705) might protect an aristocrat’s glasses from a camel’s jostling gait. Cubed sugar is now common, but decades ago it was imported in cone form, cut with special shears (temoda ton essukor) and pulverized by cast sugar hammers (tefidist) (Fig. 706). The Tuareg add considerable amounts of sugar to tea, which helps assuage hunger as well as thirst.

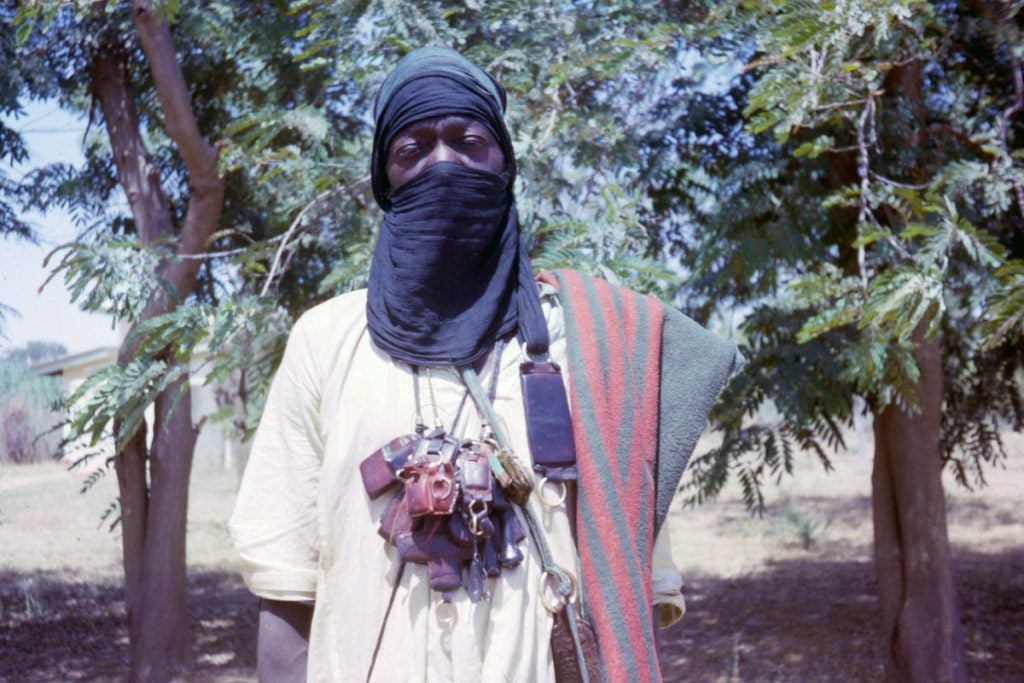

The performance of shared tea is dramatized by Tuareg clothing. Men must lower their turban’s mouth veil (tagelmust) in order to drink (Fig. 707). Formerly this meant one was highly selective about whom one drank with, for the mouth veil—which is the first part of the turban that is wrapped—is a customary protection against evil. The “evil mouth” and “evil eye” can supernaturally cause misfortune due to jealousy. The latter is sometimes expressed in honeyed fashion—one of the reasons nobles customarily distanced themselves from the inadan, who are professional wordsmiths as well as artists. Tea drinking is less caste-isolated today, perhaps because numerous inadan have become wealthier than many nobles, even employing some as salesmen.

Tagelmust were customarily made from fine dark indigo cotton, and worn over white, blue or indigo gowns with very loose trousers (Fig. 708). The Tuareg prefer a particular kind of indigo-dyed cloth, one which is over-

dyed, then further pounded with powdered dye until it acquires a prized and costly sheen. Both Hausa and Nupe once made these cloths, called aleshu, primarily for sale to the Tuareg. Only a few Hausa dyers still make them and they have grown even more expensive. The indigo often stains the face, hands, and nails, giving rise to another Tuareg nickname, “the blue people.” Tuareg today wear a greater variety of colors, and, in urban and foreign settings, sometimes dress in Western clothing, with or without the turban, a practice once inconceivable. More conservative men wear their hair dressed into a few braids under the turban, but urban youth are more likely to have close-cropped styles.

Clothing is still a major identity statement for most men, however. Customary dress is by no means standardized, for over 200 ways of draping the tagulmust are known, varying in meanings that indicate mourning, reserve, flirtatiousness, relaxation and more. The tagulmust, though identified with the Tuareg who created it, spread to the nomadic Wodaabe Fulani in northern Niger and, by at least the 1830s, to the settled Fulani who took over Hausa and Nupe rule in the nineteenth century. Neither group has assumed its universality, nor all of its proscriptions and subtleties, but its wrapped shape persists, with mouth veiling still practiced by numerous northern Nigerian and Cameroonian emirs and some chiefs in modified form.

The displacement of Tuareg has led to some being housed in refugee camps (Fig. 709). Others have headed for cement houses in cities such as Agadez, where gender roles reverse–men own the permanent houses, although women still own any tents in use.

Still others are the dominant presence in towns that have been majority Tuareg for a long time, such as Tahoua in Niger, where a public sculpture even references the “Agadez cross” pendants made by inadan silversmiths (Fig. 710).

Jewelry has been one of the prime catalysts for change in the lives of those inadan who cast silver and work other metals. In the space of a generation, the disasters of drought, famine, and rebellion that particularly marked the 1970s and 80s saw the enterprising inadan expand foreign patronage substantially. Many settled in towns and travel internationally to sell. Some even entered into long-term relationships with foreign firms; one set of inadan created silver clasps for purses made by high-end French leatherworking firm Hermès. Suggestions, perusal of fashion magazines and jewelry catalogues, and observations of the ornaments of nearby peoples have led to the production of key rings, bottle openers, lighter cases, and other innovations, as well as thinner, smaller versions of customary forms (Fig. 711). At first, only smiths themselves sold the works to

foreign visitors, but by 2004, nearly one-third of the vendors in one town with 62 sellers belonged to the nobility, one of many shifts in the old customary relationships between castes.

Further Reading

Bernasek, Lisa. Artistry of the Everyday: Beauty and Craftsmanship in Berber Art. Cambridge: Peabody Museum Press, 2008.

Lhote, Henri. Les Touaregs du Hoggar, 2nd ed. Paris: Payot, 1955.

Loughran, Kristyne. Art from the Forge. Washington, DC: National Museum of African Art, 1995.

Loughran, Kristyne. “Jewelry, Fashion and Identity: The Tuareg Example.” African Arts 36 (1, 2003): 52-65; 93.

Milburn, Mark. “The Rape of the Agadez Cross: Problems of Typology among Modern Metal and Stone Pendants of Northern Niger.” Almogaren 9-10 (1978): 135-154.

Nicolaisen, Johannes and Ida Nicolaisen. The Pastoral Tuareg, 2 vols. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

Rasmussen, Susan J. “Making Better ‘Scents’ in Anthropology: Aroma in Tuareg Sociocultural Systems and the Shaping of Ethnography.” Anthropological Quarterly 72 (2, 1999): 55-73.

Rasmussen, Susan J. “The People of Solitude: Recalling and reinventing essuf (the wild) in traditional and emergent Tuareg cultural spaces.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 14 (3, 2008): 609-627.

Rasmussen, Susan J. “Performing Culture: A Tuareg Artisan as Cultural Interpreter.” Ethnology 49 (3, 2010): 229-248.

Rodd, Rennell. People of the Veil. London: MacMillan, 1926.

Scholze, Marko and Ingo Bartha. “Trading Cultures: Berbers and Tuaregs as Souvenir Vendors.” In Peter Probst and Gerd Spittler, eds. Between Resistance and Expansion: Explorations of Local Vitality in Africa, pp. 69-90. Münster: Lit Verlag Münster for the Institut für Afrikastudien Universität Beyreuth, 2004.

Seligman, Thomas K. and Kristyne Loughran, eds. Art of Being Tuareg: Sahara Nomads in a Modern World. Los Angeles: Cantor Art Center and UCLA Fowler Museum, 2006.

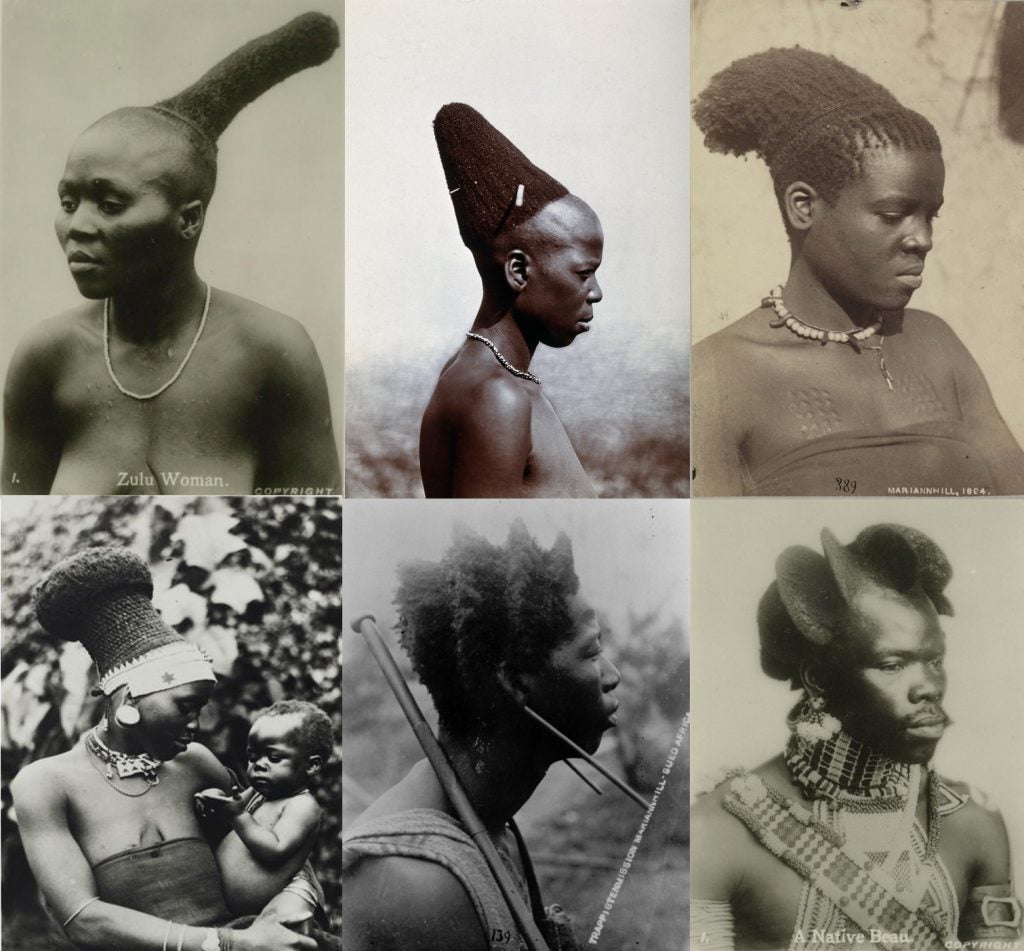

Zulu Arts of Beading, Brewpots, and Utensils

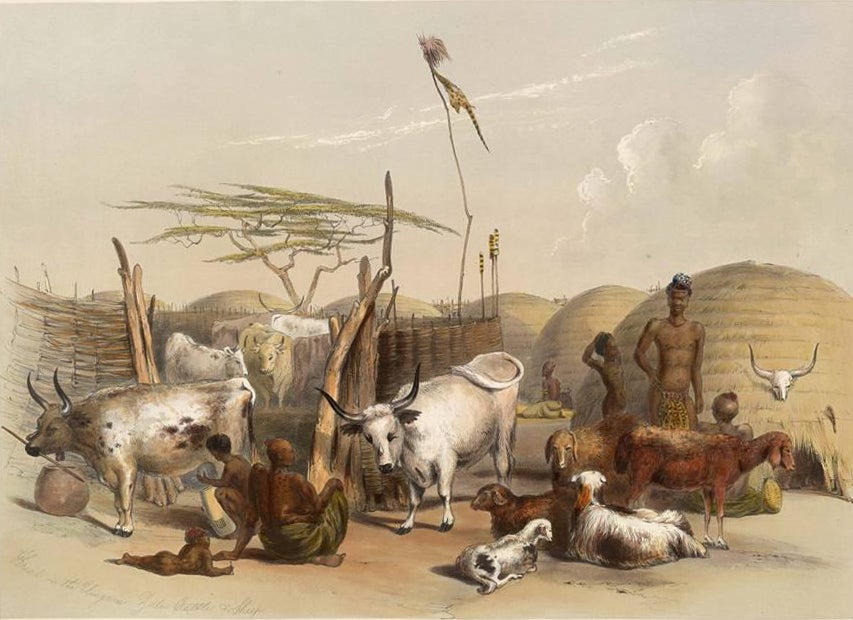

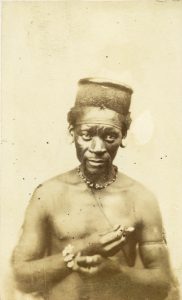

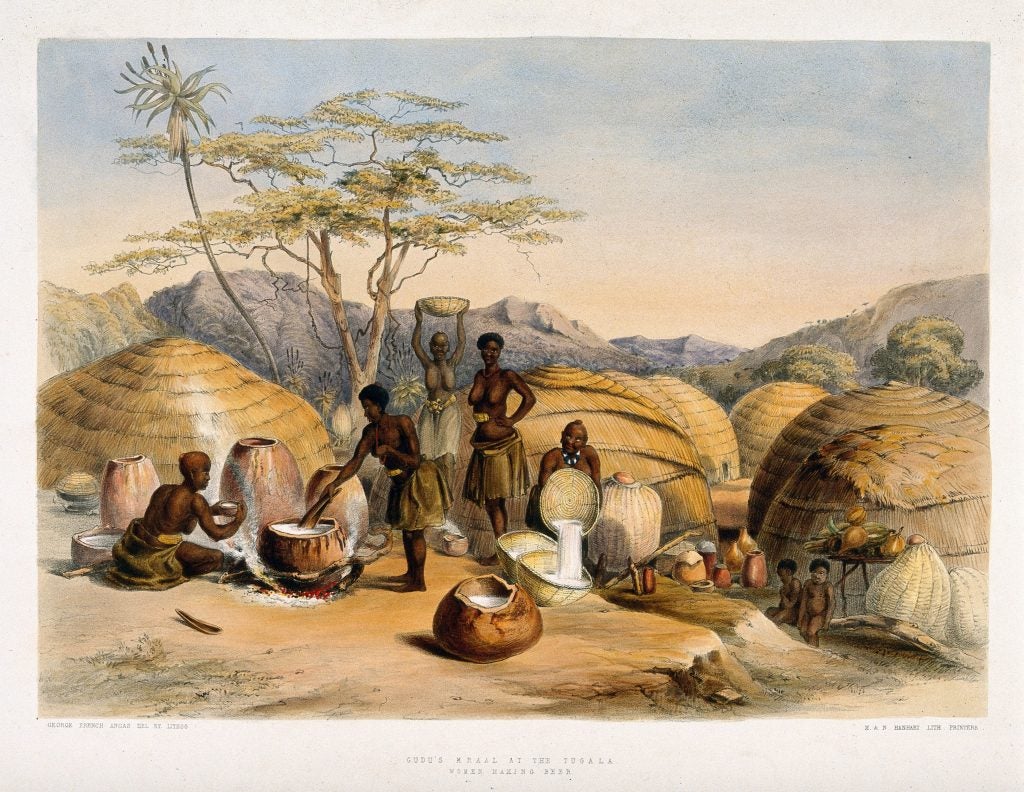

The Zulu formerly had a rural, cattle-rearing nomadic culture (Fig. 712) and many older household objects reflect these ties, incorporating abstracted cattle legs, tails, and other bovine references. However, today the Zulu form the largest ethnic component of Johannesburg, South Africa’s

most sizable city, as well as Durban, its third largest city and busiest port. The shift to urbanism began over a century ago; the Zulu are by no means newcomers to metropolitan life. The British 1879 victory in the Anglo-Zulu war disrupted the Zulu kingdom structure shared by many—though not all—Zulu and their tributaries. The British and Boers increased control over land, and, by the close of the century, had instituted mandatory poll taxes for men and hut taxes on each structure. Payment had to be in government currency, which meant at least temporary shifts in money-earning, since the Zulu were cattle raisers unused to coinage and banknotes.

This change prodded many men to periodically migrate in order to work in European-established settlements, providing access to a new cash economy, trade goods, and completely different forms of employment. In the many intervening decades, some stayed in the cities. Household separations were frequent due to one-gender mining camps as did apartheid’s domestic worker arrangements, which allowed women and their children to be housed in a small outbuilding on their employers’ property, but banned adult men from staying there. An ever-increasing movement to the cities continues in post-apartheid times, overcrowding both the former segregated “suburbs” like Johannesburg’s Soweto and other city regions. Although those Zulu who have acquired wealth through politics, law, entertainment, sports, and other professions have luxurious homes, overcrowded urban living is the norm for most, as depicted in the photographs of Zulu artist Zwelethu Mthethwa (Fig. 713). Single rooms or rooms-and-parlors are rental spaces whose walls are papered in newspapers, posters, and ads, and whose cleanliness showcases often sparse possessions (see other Mthethwa photos HERE).

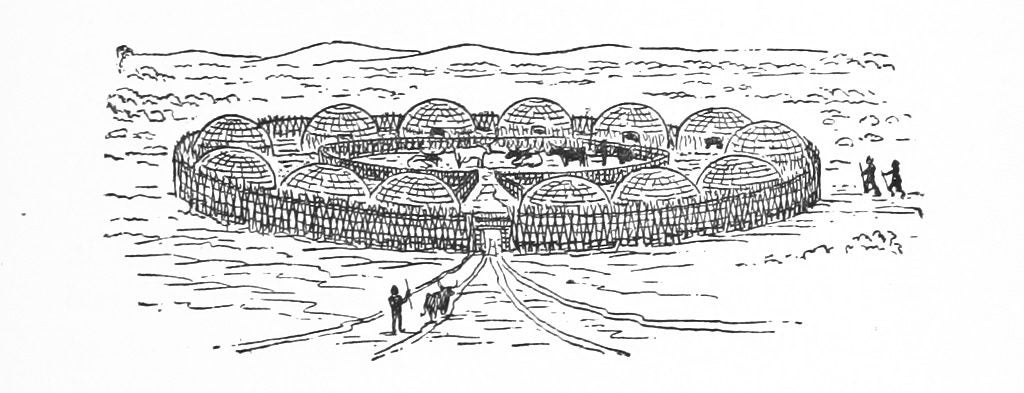

Other Zulu—particularly women, children and old men—still remain in the countryside of KwaZuluNatal, their lives tied to cattle and the semi-nomadic lifestyle of their forebears. Many city dwellers plan to retire to the countryside for a less frantic existence, but rural Zulu certainly do not live in isolation from metropolitan culture. Family members live and work in urban areas, visits to the city are made, local stores stock city goods, and locally-made items are sold to city galleries or tourist vendors. In the nineteenth century, those Zulu under the ruler Shaka’s (c. 1787-1828) royal descendants also lived in towns such as Umgungundlovu, which had about 1500 homes and many more inhabitants. These settlements were circular in design, the ruler’s home placed furthest from the entrance. Subjects lived in several layers of round houses around the circumference of the

community—which could reach two miles—with cattle holding areas (known as kraal in Afrikaans and English and isiBaya in Zulu) between them. The military used the huge kraal at the center as a parade ground. After the British broke the royal system, smaller household settlements replaced this arrangement, taking a similar formation (Fig. 714). The isiBaya was quite literally the core of the homestead. Households initially had one wooden stockade surrounding the central kraal, while a second, outer stockade encircled the dwellings. The isiBaya centralized the household’s wealth

through cattle, which served as a bride price for legitimate marriages and also provided food, hides for clothing, and dung for fuel. Deceased members were buried there, and thus ancestors and cattle remained interlinked at the heart of the home. Houses were distributed around its edge in the area between fencing according to hierarchy: the Great House (iNdlunkulu) stood on that point of the circle opposite the stockade entrance, and households derived from the senior wife’s line occupied the space known as the right-hand-side, while those of lesser wives and their offspring occupied the left side of the arc. Each wife had her own home that also housed her young children, and sons who married built new houses in the household for their own wives and children. Men had no particular house of their own, but visited their wives’ houses successively.

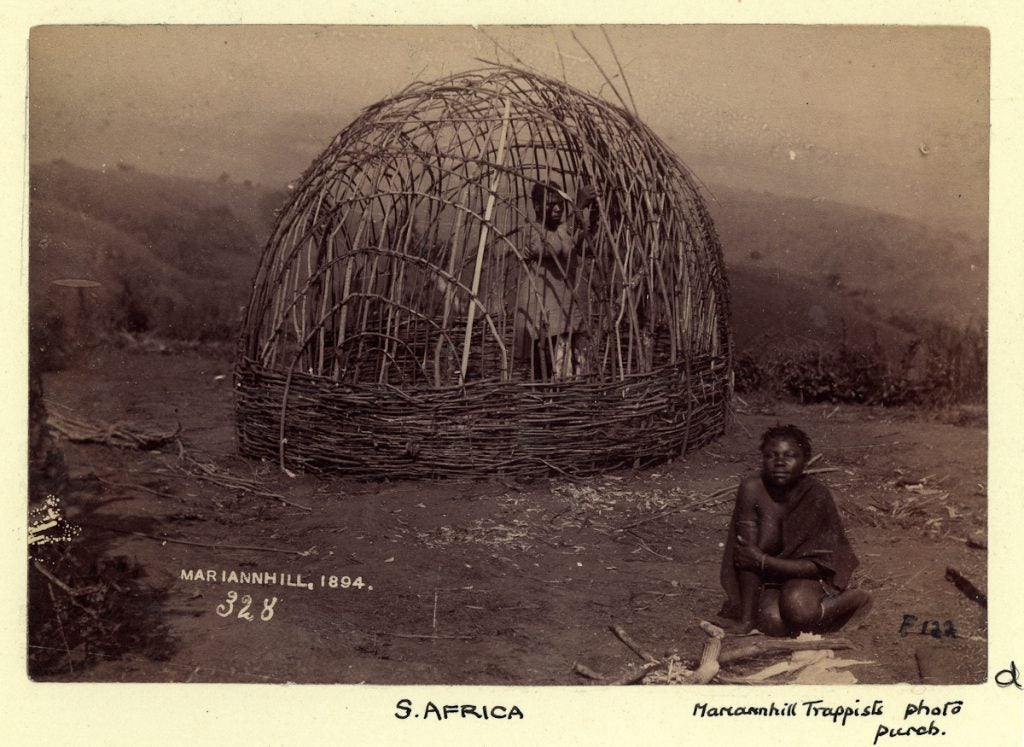

Like the homes of most other African pastoralists, older-style Zulu houses (indlu) were made

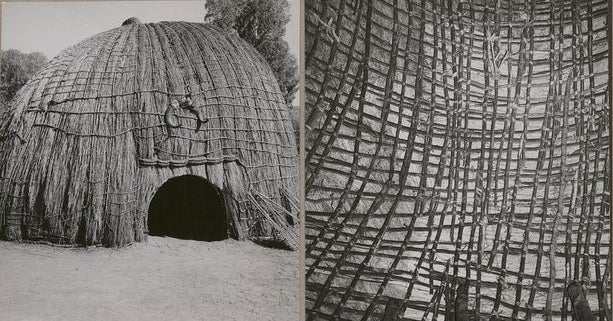

of readily available, lightweight materials, even after the adoption of farming made settlements more permanent. Males dug a trench as a foundation, sinking long saplings into it to act as an armature. Bending these saplings, they created arcs, tying on other crosspieces to produce a latticed dome (Fig. 715). Thatching was applied in fairly short layers (Fig. 716), and, if the inhabitant were elderly, additional grass ornaments might be added. If the home were large or heavy thatch covered its frame, pairs of interior supports with crossbeams ensured its shape would remain fairly hemispherical and avoid collapse. At the top, some homes had a finial bound off that incorporated a medicine against lightning. In the colder Zulu regions, woven mats were layered over the exterior thatch for extra insulation.

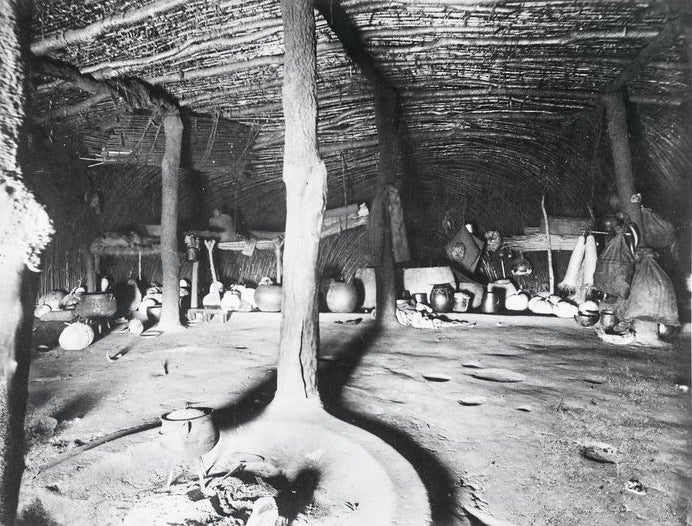

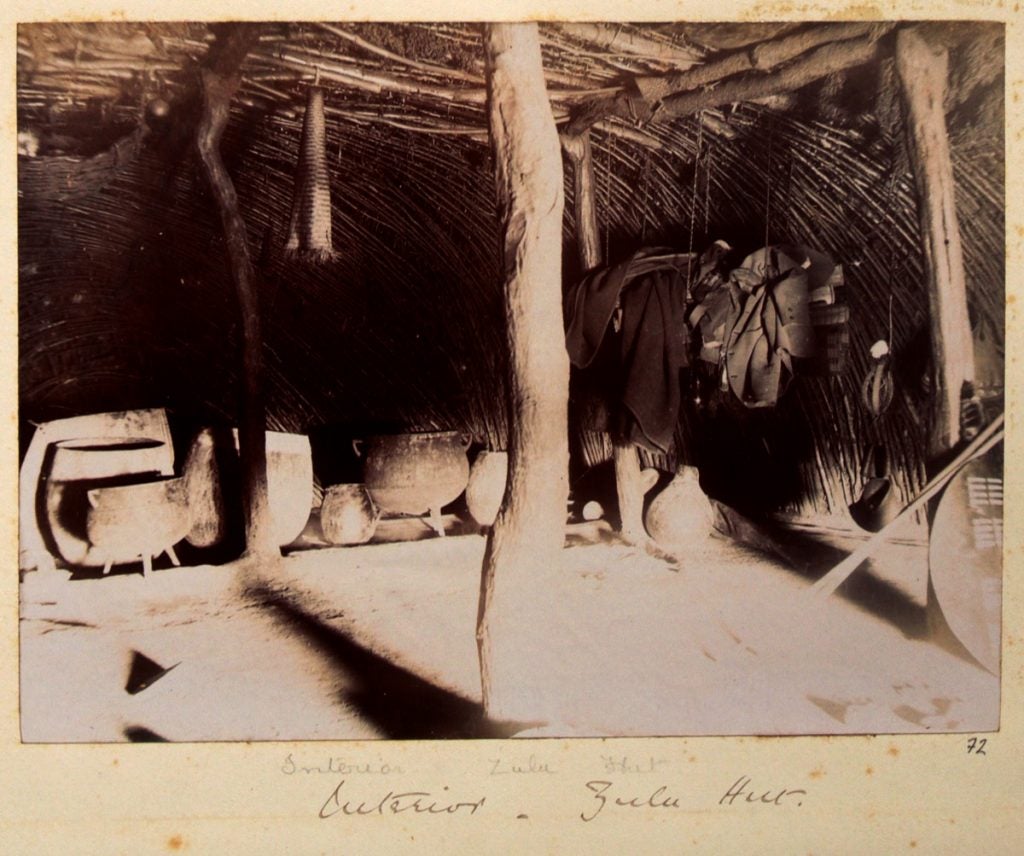

A circumference of nearly 16.5 feet was common, a span large enough to house several inhabitants in comfort (Fig. 717). Although regional daytime temperatures often stay in the 70s ˚F, or above, they can fall to the 50s ˚F in winter, or drop at the higher altitudes of this often mountainous region. Interiors, therefore, had a central hearth to provide warmth, as well as to cook. Smoke could escape through the thatching. In the past, when someone died, their home was torched, and neighboring structures were either moved in their entirety, or the underlying framework was freed of its thatching and shifted, even if a short distance.

These kinds of homes were still common through the 1950s, but changes occurred. Decades before, maize had become a crop, encouraging settlement. Goats joined cattle in the livestock realm, and the kraal space shrank. The outer stockade was abandoned, and granaries were placed near household entrances. Once many householders became one-wife Christians, moving from house to house no longer was a male option. These effects cumulated in smaller households.

Less thatch was available as grassy expanses turned to farmland. In subsequent decades, earth or cement replaced fiber in the creation of still-

round homes topped by thatching (Fig. 718). These were usually whitewashed or painted in solid colors, unlike contemporary creations of Sotho, Ndebele, and other South African groups. Some took rectangular forms, which made the inclusion of Western-style furniture easier. Zinc roofing’s adoption has since become almost ubiquitous (Fig. 719), as it has throughout the continent for reasons of status.

Rural Zulu life and its older manifestations have not totally vanished, however; they have become tourist draws. Several villages have been erected to recreate a historic lifestyle for visitors, à la Williamsburg. At least two are partial reconstructions of the historic royal capitals of Shaka’s successors King Dingane and King Cetshwayo. Others have been constructed near popular scenic sites. A recent Internet tour promotion touts one spot as follows: “Our first stop is an authentic cultural village where dancers perform an ancient dance to the beating of African drums. Sample traditionally brewed Zulu beer and watch women craft clay pots and intricate Zulu beadwork.” PheZulu Safari Park offers a village tour with “traditional beehive shaped thatched huts,” as well as Zulu dancing, wildlife encounters, a restaurant, and gift shop, while Shakaland is billed as “the oldest ‘Zulu Cultural Village,’” erected as a set for the South African television mini-series Shaka Zulu (1986) and also used in the 1990 film John Ross. Numerous other travelers’ destinations also keep the past visible (Fig. 720).

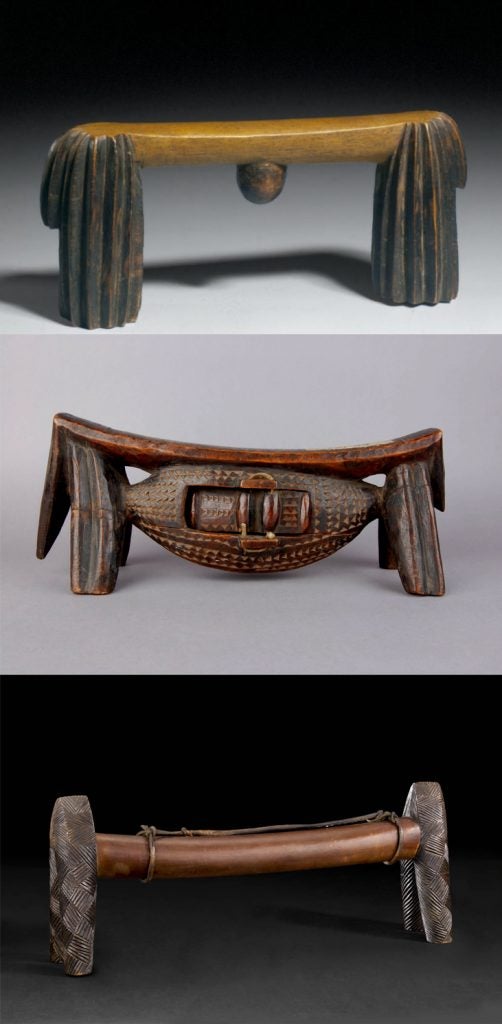

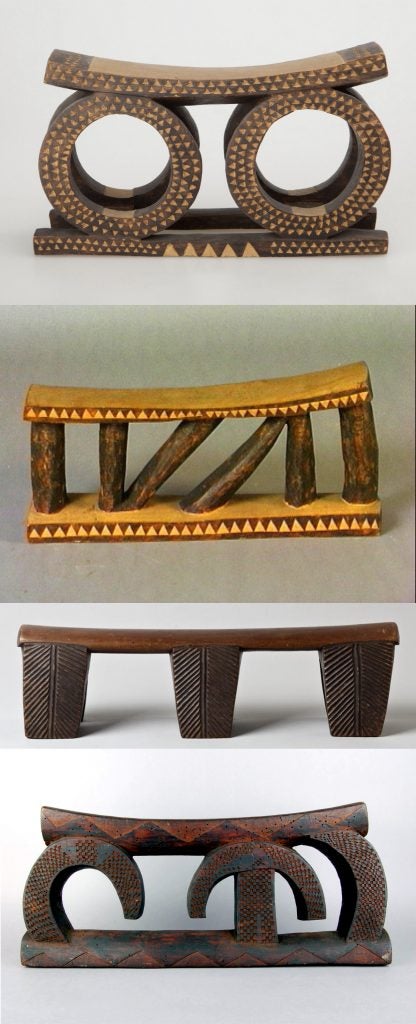

Interiors were spare. Different types of mats were used for sleeping, as plates for eating (isithebe) (Fig. 721), or for sitting. Other furnishings were usually limited to headrests, wooden milk pails and meat platters, and other containers and implements. Goods were usually stored around the perimeter (Fig. 722), making active use of the space where the building’s arc made adult use impossible. Beaded garments and jewelry, as well as snuff holders and other personal goods, were often tucked into the sapling grid, out of children’s reach. Because those with bad intent could use a man’s most intimate possessions to cause him harm—headrest, attire, eating utensils, mat—only his senior-most wife could touch these objects. The great house

within a compound had a curving earthen ledge that served as an altar. This part of the home was farthest from the entrance, providing a dark place that the ancestors found appealing. Ritual items were kept there, and it served as a place for communion with ancestral spirits. Urban Zulu choose a room for this purpose and still store specialized items there, such as the spear used for daughters’ coming-of-age ceremonies.

The formerly elaborate Zulu hairstyles (Fig. 723) made headrests (izigqiki) imperative, although they are seldom used today. Brides usually brought these to the marriage, although some authors state the groom was to provide one for himself and one for the new wife, while she would instruct the carver to include specific motifs. The designs often mirrored designs on her engagement beadwork, which was treasured. When the 19th-century Zulu kingdom was active, headrests were highly prized. They might be buried with the owner or be handed down as revered–but no longer used–heirlooms. Daughters could inherit them and carry them to their husband’s house; they remained a concrete tie to their own lineage and ancestors.

Those who lived in the core kingdom areas often had

headrests sparely decorated with amasumpa, wooden bumps or “warts” (Fig. 724), although this ornament was not used in other Zulu regions. Numerous styles of headrests exist, including many double examples that were used when a husband shared his

wife’s house (Fig. 725). The rounded uprights on some izigqiki (Fig. 726) are meant to evoke cattle legs, and thus the herd and cattle’s ability to connect with the ancestors. Other headrests have tails or legs that also suggest cows (Fig. 727). These cattle allusions may also refer to ancestral-inspired dreams produced when sleeping. The intensive trade and tribute that took place within the nineteenth century resulted in a variety of styles (Fig.

728), some created by subject peoples.

Many other household objects also have connections to cattle, for milk products are an essential part of the Zulu diet, as they are for many pastoralists. Raw milk is usually avoided, however. Cattle handling is a male activity, since married women are most closely associated with a polluted ritual state that makes cattle, people and plants vulnerable to illness and death. Girls may interact with family cattle, as long as they are not menstruating, but boys do the milking, using wooden milk containers (ithunga) (Fig. 729) as temporary receptacles. These are ordered by the male heads of households. Some are footed; others bear amasumpa or even breasts. The ithunga is symbolically female, but women are not allowed to touch them; girls singing at coming-of-age ceremonies compare it to the vagina. The extrusions at the side allow a better grip between the knees during the process. After milking, the boys then transfer the liquid to calabashes or hide containers to ferment, overturning the wooden pail to dry. Subsequently, the milk separates into thin and clotted liquids—whey and curds. The latter are known as amasi, curdled sour milk, similar to cottage cheese or yogurt. The word amasi is incorporated into the descriptive names of certain whitish Nguni cattle: inkomo engamasi evutshiwe, or “ripe milk”. Amasi still can only be shared with those who are blood relatives of the householder, thus excluding women who have married into the family. Ritual prohibitions also disallow amasi consumption during menstruation or mourning, as well as during the girls’ seclusion period for coming-of-age ceremonies. Amasi is popular among many South African groups, and commercial dairies produce pasteurized versions today.

Commercial goods have displaced most wooden and terracotta cooking and serving vessels, with imported iron cooking pots already staple goods in the late nineteenth century. The basic Zulu diet consisted of milk products, boiled porridge, and cooked greens. Ladies were used for cooking and serving. Long-handled spoons for eating amasi from a communal terracotta bowl were once essential, but amasi is now more often drunk directly or poured over corn meal (“mealie-meal”) pap. Spoons were valued, carefully kept in a dedicated bag, personal to their owner. Most eating spoons have a bowl that meets the stem at a sharp angle, with very small sections of decoration on the latter (Fig. 730). A few are figurative, with an elongated female figure acting as the handle (Fig. 731). Even non-figurative spoons may allude to a woman’s body, their pointed bowls like a head with a desirable pointed chin, inclined in the respectful pose women take with their inlaws.

Beef was a fairly infrequent addition to the Zulu diet, but cattle and goats were slaughtered for feasts honoring the ancestors. Pouring beer over the goats’ backs in advance signified their dedication to the dead, as beer had ancestral associations. Men roasted the meat, which was served on wooden platters. Those platters from the core Zulu areas once ruled by Shaka often included amasumpa projections (Fig. 732), as did some headrests and milk pails. The platters stand on low legs, and sometimes the amasumpa were placed on the underside, where they would have been almost invisible to diners. Their decoration, however, would become evident when the platters were hung by their usual lugs, or when one platter was inverted over another to keep meat warm or ward off flies. Fat is often applied to the wood, as well as draining onto it, so dull examples were probably never used.

If meat was most commonly consumed during ancestral festivities, traditional beer made from sorghum was even more closely associated with them. Homemade beer is still a vital part of Zulu culture. Women are typically brewers, and legend states that Nomkhubulwane, the Zulu goddess in charge of women’s farming and growth, first taught them the technique. Women also use clay from her earth to create the pottery necessary for proper preparation and serving of this nutritious, grain-based drink, which is only about 2% alcohol. Large natural-colored pots rubbed on the outside with cattle dung serve as vats, and are placed in a family brewery, a small dedicated building kept warm to promote fermentation. Brewing takes from three to seven days, and basketry caps cover the vats during the process in order to keep out dust and insects. Afterward, the beer is strained through fiber bags and woven skimmers remove any flotsam from the grain (Fig. 733). Though most Zulu women know how to make beer, those considered to have “tasteful hands” are sought to produce the drink for special celebrations. Beer is linked to hospitality, and drinking is tightly tied to social and ceremonial life—it is brewed for babies’ naming ceremonies, coming-of-age ceremonies, dispute settlements, weddings, and funerals. Beer is also sacred. Women who are not ritually pure—pregnant, menstruating or breast-feeding—cannot prepare it. At the end of the brewing process, the vat is placed on a raised altar to the ancestors in the dark recesses dedicated to them at the back of the main compound home. Ancestors also have a pot that always contains a small amount of beer at their disposal. Drinking takes place at ground level and serving vessels stay there as well, to honor the ancestors buried there by dropping fresh beer’s skimmed foam to the ground next to the pot as an offering. Ancestors are themselves sociable, and grow annoyed if the household doesn’t hold feasts with beer and meat, for those occasions are held in their honor and enhance their posthumous reputation.

The decorative raised bumps (amasumpa) that occur on wooden containers appear even more frequently on pots, sparingly placed in asymmetric clusters that often conform to geometric shapes, such as triangles, circles or six-pointed stars. Some scholars associate their patterns with long-abandoned young women’s abdominal scarifications, whose location intentionally conjures thoughts of fecundity. Others link them to cows’ teats or to herds, symbols of nourishment and wealth respectively. Incised decoration on pottery is also common, and both approaches generally appear on a pot’s “shoulder” (Fig. 734). The dark color of most serving vessels further associates them with family forebears, who are said to prefer darkness, and only black vessels are used at ritual ceremonies for the ancestral protection they suggest. These pots’ distinctive finish is achieved by first burnishing them with a pebble, reducing oxidation during the open pit firing (which employs cattle dung as well as wood) by using leaves or grass, then applying soot, ash, and cattle fat to the completed terracotta and refiring it. Both dung and fat call the ancestors to mind as well, since all cattle products are linked to the family dead. Zulu pottery is known for its extremely thin walls and graceful form. Pots with necks (uphiso) (Fig. 735) are used to transport beer for celebrations to minimize spillage (Fig. 736), and leaves are sometimes stuffed into the neck as a further preventative.

Depending on the gathering, a fairly large pot may be placed inside a ring of guests, who are then served with a ladle, or individual vessels may be distributed. People use neckless pots (ukhamba) to drink from, and basketry caps (imbenge) protect their contents (Fig. 737). Once drinking begins, an upturned cap indicates a refill is requested. These vessels are not changeless. Excavations suggest that blackened beer vessels emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, and were preceded by tightly-woven beer baskets—also still manufactured. In more recent times, amasumpa decorations spell out words or form recognizable motifs, and are not individually attached as they once were. Instead, in order to save time, a raised band is applied to the pot and sliced with a knife for a similar, but time-saving, effect. Although most Zulu pot types once used for cooking and serving food have long been replaced by manufactured goods, those linked to beer are still crafted, underlining the ritual aspects of the traditional brew. Production has also expanded to fill the demands of non-brewing patrons, who buy works for display purposes and internationally promote the work of select master potters.

Zulu pottery constitutes one art form that has continued into the twentieth century, but not only because of continued home brewing with its social and ritual aspects. Recognition from the South African art world has led to an elevation for potters. Their works are now displayed in galleries and museums, and the potters’ names are now recorded, their work discussed and emulated, inspiring academically-trained artists who did not grow up with this tradition, such as Ian Garrett. On a smaller scale, similar accolades are now showered on basketmakers. Men used to produce baskets and mats, but missionary influence shifted fiber crafts to women, following European patterns. By the 1970s, production of intricate beer baskets (Fig. 738) had nearly ceased, but a revival and expansion have since taken place. As in Botswana, the new baskets are rarely used, although they are functional. They have become display pieces for non-Zulu, rather than household objects, and artists vie with one another to create patterns far more intricate than anything made a century ago.

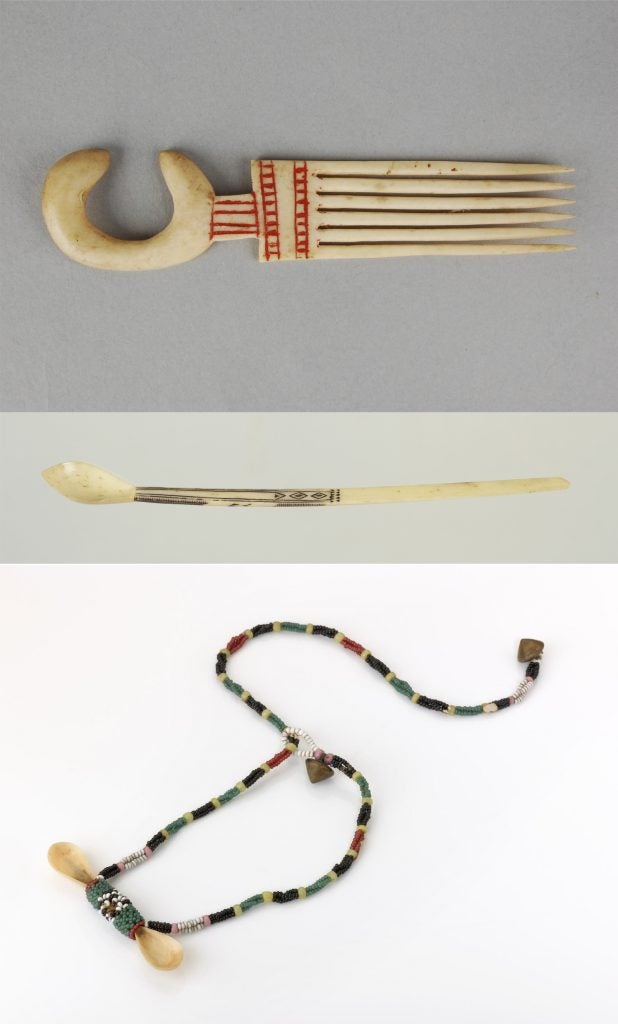

Most other household and personal items have gone through a lot of changes, unsurprising considering the multiple political and social upheavals of the past century and a half. Although Zulu snuff-taking is still prevalent, the intricate and varied containers and implements associated with its past use have vanished. The Zulu state that snuff heightens awareness. Non-tobacco snuffs can be used for medicinal purposes—the powdered bark of the umkwangu tree and the powdered root of iyeza (Anemone caffra) both cure headaches. Most snuff-taking did employ tobacco, however, in the form of a fine, dry powder meant to be inhaled with a subsequent sneeze. A common offering to the ancestors, it had a ritual dimension as well as a secular one. Snuff-taking was most often a social activity, and the public use of implements provided opportunities to display taste and wealth. Both men and women kept snuff on their person. Women used small bead or wire-decorated gourds Fig. 739), while men tended to use horn containers that were often made to be tucked into a gauged earlobe or perform double duty as hair

ornaments. These were not necessarily singular objects—several nearly identical, delicately-carved versions have survived the past century. Men and women’s hair was also the site of snuff spoons, carved from bone in an extensive

assortment of shapes (Fig. 740), some with C-shaped bowls, others with zig-zagging stems. Although these were used to convey snuff to the nostrils (Fig. 741), many were comb-shaped in order to fix them more securely in the hair. Some larger wooden containers, formerly thought to be milk vessels, may have held snuff at gatherings, or were commissioned by Europeans (Fig. 742). None of these items are made any longer, since commercial snuff containers easily fit in the purses or pockets that formerly didn’t exist.

Zulu dolls were also often carried, but by young women as meaningful display pieces, rather than toys. Over a core of wood or cloth, early 20th century dolls were cylindrical, covered with beaded patterns except for their featureless faces (Fig. 743). Hair was represented by fiber or beaded strands in a style once popular with unmarried girls, similar to that now worn by female ritual specialists. Although childless women sometimes carried them, hoping to induce pregnancy, these were usually the property of teenagers. The dolls were frequently attached to cording that allowed them to hang over the shoulder. Young women offered their dolls

to boys to initiate romantic relationships, but this token of affection only bound the giver, not the receiver. Over the course of the twentieth century, the dolls grew much larger, gaining beaded facial features and hats. After apartheid was instituted in 1948, travel restrictions prevented young women from visiting sweethearts working in the cities. Instead, they often had studio photographs taken of themselves with their dolls, sending the photographs instead, a practice that continued until apartheid’s end in 1994. Zulu doll use is part of a widespread southern African practice that includes the Sotho, Xhosa, Tsonga, and others.

In the nineteenth century, clothing varied according to age, marital status, and social rank. Despite the frequently chilly weather, many Zulu men and women at this time wore dress that frequently left them with bare chests, arms, and legs. Standards of modesty required maidens to bare their breasts, while all males who had reached puberty wore prepuce covers over the glans of their penis. These varied in shape and material, made of basketry, banana leaves, calabash, leather or wood; fiber examples usually belonged to married men. They usually took either a cup-like or globular shape (Fig. 744), but were usually hidden by a loincloth of animal tails or pelts. While exposure of the penis as a whole was not considered an embarrassment—indeed, younger men occasionally wore naught but the penis cover—an exposed glans and prepuce were tantamount to vulgarity. The monarch Shaka required two European men resident in his domain to wear these covers, even though they wore trousers. Absence of a prepuce cover left the wearer vulnerable to evil intentions and supernatural tampering, which could also occur if the cover were handled by another. Normally, they were destroyed at the owner’s death.

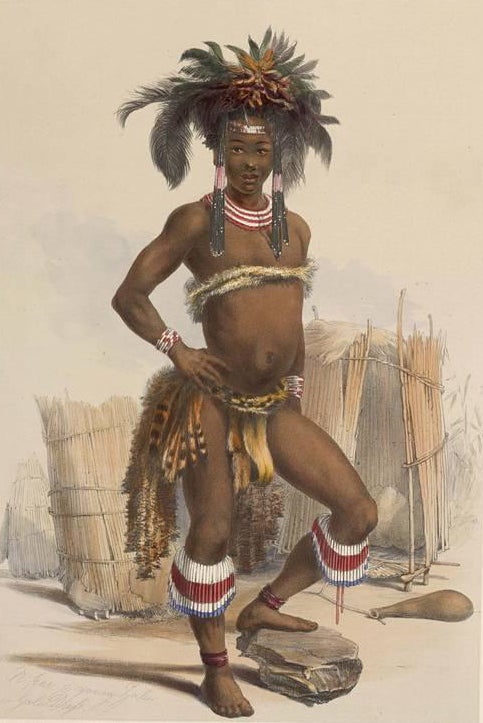

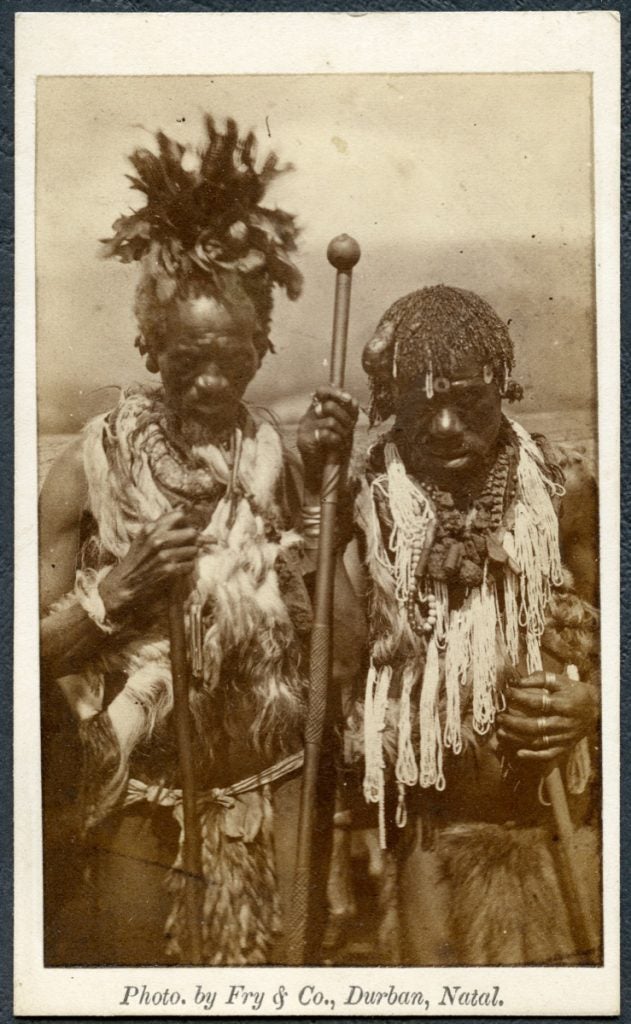

Daily dress contrasted sharply with a warrior’s formal attire, which included feathers that added height (Fig. 745). In the late nineteenth century, men’s rural styles were relatively independent of European directions. They wore a variety of hairstyles when young, replacing them as married men with a beeswax and sinew-coated fiber ring sewn into the hair (Fig.

741). After the 1879 defeat of the Zulu kingdom, all important adult men could wear necklaces made from imitation lion’s claws (Fig. 746). These had also been worn by other Nguni groups, but were formerly restricted to royal use, then to regional chiefs and counselors. Like other South African men in the nineteenth century, Zulu males carried knobkerries (Fig. 747), wooden clubs that served as close-quarters weapons for fighting or hunting game. The British banned large examples, insisting in the Cape area that the knob must be small enough for the owner’s mouth to contain it, while in Natal their numbers were restricted. They continued to be male accessories, even as the warrior ethos was restricted. Handed down from father to son, and became heirlooms that had a ritual focus. Under twentieth-century apartheid, urban migrants risked arrest for carrying them, but members of urban ethnic associations did so anyway when carrying them to Sunday boxing matches. Night watchmen were permitted to use them, and employed more colorful telephone wire to braid patterns onto the sticks and knobs.

Change has greatly affected Zulu dress. Urban migrants adopted Western dress, although ethnic affiliations continued to appear in twentieth-century

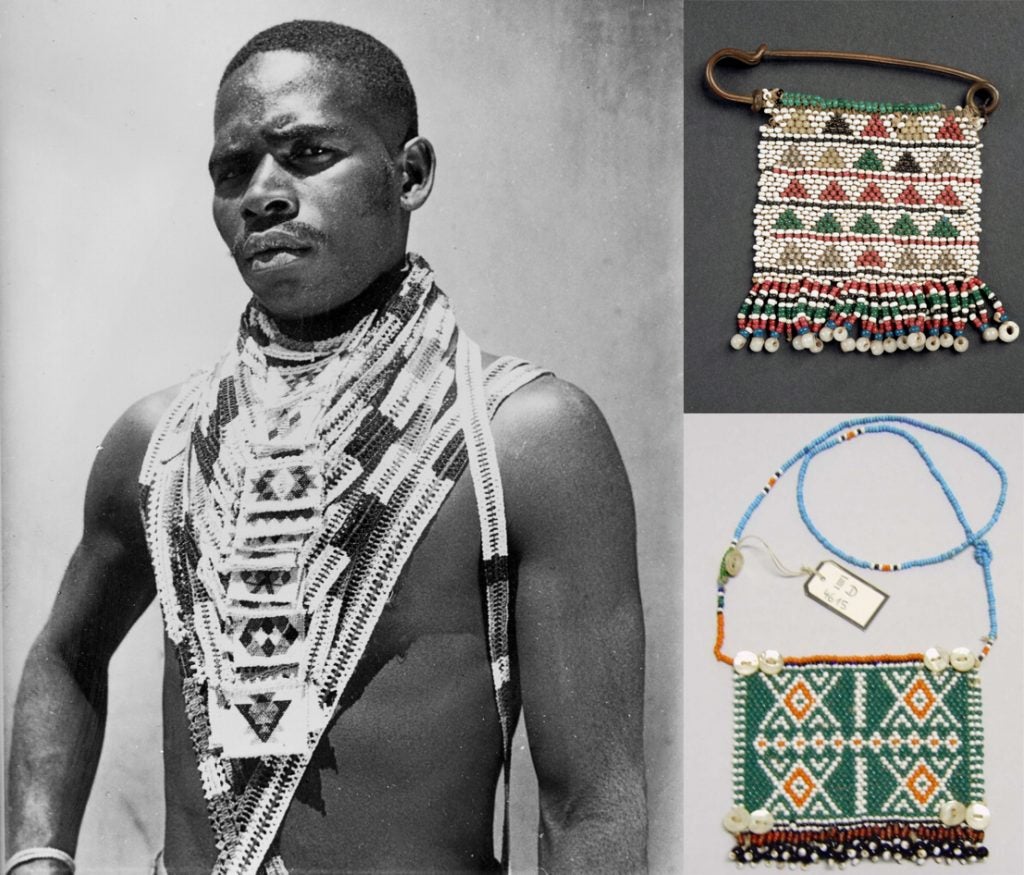

photographs via accessories or beaded attire, which might include a band added by a wife or girlfriend to purchased clothing, or completely beaded vests (Fig. 748). Today, most Zulu men and women wear sweaters, trousers, skirts, knit caps, and other manufactured clothing, though ceremonial occasions and events encouraging ethnic pride require dress based on earlier fashions. In general, however, Christianity and the expectations of former white rulers imposed absolute shifts from exposure to a more covered body in the city, and influenced rural areas as well. Under apartheid, however, oppositional use of traditional dress became a form of political subversion, and studio portraits often showed girls in traditional beadwork and uncovered breasts up until the early 1990s (Fig. 749). Younger men wore (and continue to wear) beadwork made by admiring females. These love gifts could not be presented to prospective boyfriends until a girl had gained permission from her seniors to enter into courtship relations. Girls made them themselves, using glass imported glass beads. The popular rectangular-tabbed “love letters” include coded messages, although their use is idiosyncratic and colors are uncodified (Fig. 750). Locally-made beads from ostrich shells, bone, and other organic materials had decorated clothing and persons for several millennia.

European bead importation increased significantly in the mid-19th century, transforming Zulu

clothing and ornamentation as beads became more readily available. These seed beads—the same time used by Native Americans—

Tropenmuseum, TM-10004293. Creative Commons CC BY SA 4.0. Right top: Zulu, South Africa, 20th century. H 2.76″. Afrika Museum Berg en Dal, AM-1-223. Donor Congregatie van de Heilige Geest (CSSp.). Creative Commons CC BY SA 4.0. Right bottom: Zulu, South Africa, 20th century. W 4.12″. Collected by H.K. Wagner. Ethnologisches Museum | Afrika. © Foto: Ethnologisches Museum der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, III D 4615. Creative Commons BY-NC-SA.

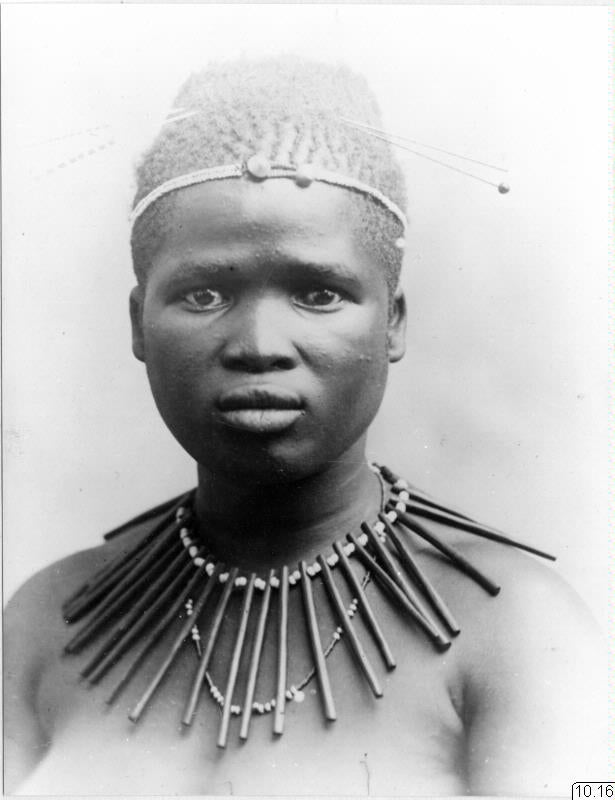

intensified color in the dress of many southern Africa groups, and were a staple of women’s art. In the mid-nineteenth century, women’s dress was made primarily from cow leather or goatskin (Fig. 751), or even from fiber (Fig. 752). Betrothal accorded young women the right to wear hide skirts; longer versions were scented and restricted to married women. Beaded accessories indicated wealth in the 19th century, since imported beads were still expensive at that time. Early beadwork was striking but limited in scope; beaded headbands and necklaces, flowers, and even porcupine quills drew attention to the face. As beads became increasingly available, female dress grew

increasingly complex. Varying according to region, a series of decorated aprons or caches-sexe (Fig. 753) became de rigueur, as did leg decorations, belts, and other ornamentation. Girls also made necklaces of the “love letter” type for their own use, and wore other kinds of jewelry as well, such as necklaces from scented strips of wood, separated by spacer beads (Fig. 754).

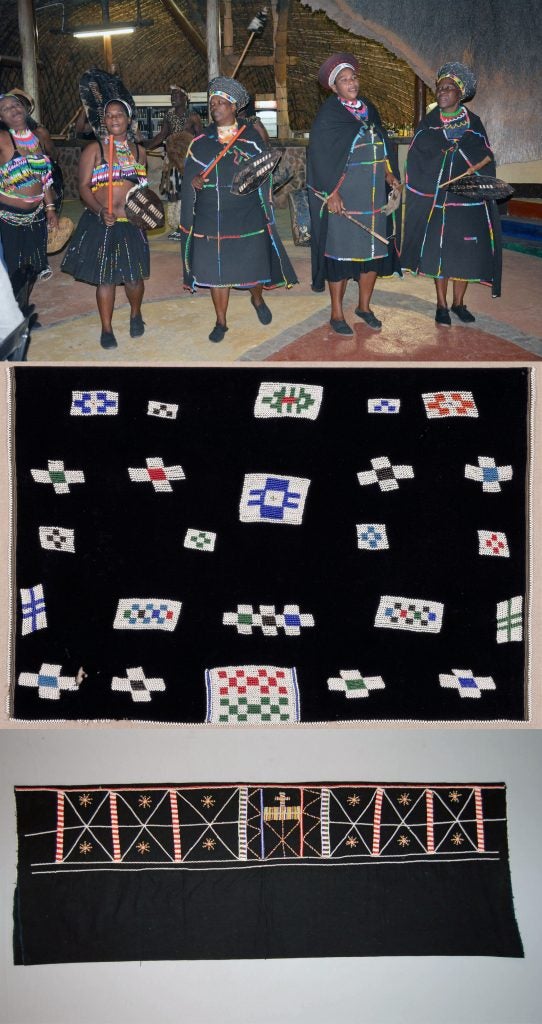

Over time, both Zulu accessories and dress continued to change. Plugs for gauged ears grew popular ca. 1950, then dropped out of fashion by about 1990 (Fig. 755). Dark manufactured cloths with minor

beaded motifs became de rigeur for married women (Fig. 756) and are still worn. Festival and daily dress often also include printed shweshwe cloths, formerly imported from Europe and now manufactured in South Africa.

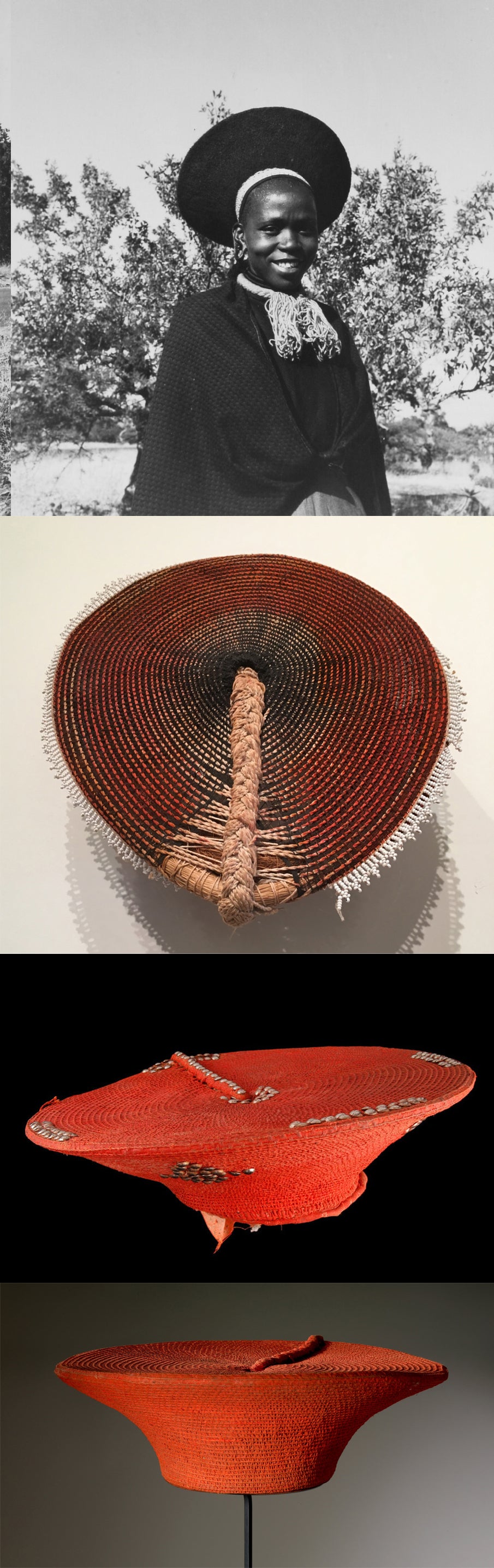

Women’s hairstyles reflected marital status. By the late nineteenth century, wives’ coiffures

(isicholo) were vertically extended with the addition of woven grasses or false hair into a conical shape with a basketry armature, held by a mix of pomade and red ochre, with headbands at the sometimes shaved hairline. The turn of the century saw a gradual transformation of this hairstyle into a hat/wig of the same name, its shape varying according to district. In the Tugela Ferry area, its shape was shallow and broadly flared, while in some regions it became cylindrical. At first it had a basketry base overlaid with a hair and string netting, covered with the red ochre pomade; red yarn was used subsequently as well. In order to maintain their shape, leaves were often stuffed into the edges of the isicholo (Fig. 757). Initially fairly plain, sometimes beaded bands were added in the twentieth century, and color range expanded. Today these are no longer daily wear for most women, but may appear for festive occasions, accompanied by beaded headbands (Fig. 756 top).

Zulu arts were originally sleek and geometric, permeated all phases of daily life. In part, this was possible because cattle herders have a substantial amount of free time to make objects. A shift to urban life and salaried jobs robbed many Zulu of that leisure, and changes in lifestyle made many prestige objects used by aristocrats unnecessary.

New arts arose, however. Introduced by British immigrant Sir Marshall Campbell in 1892, rickshaws began transporting Durban citizens, with Zulu men working as pullers. At that time, the rickshaws were not owned by the pullers, and their appearance was plain. Competition among the pullers was considerable; in 1904, over 2000 pullers were government-registered. This created a need to stand out, and they began to both decorate their rickshaws and wear headpieces that featured bovine horns. At first, these were fairly simple (Fig. 758), but as the century advanced, so did their complexity (Fig. 759). Feathers–part of traditional Zulu male headgear–were added, and new beaded attire was invented.

As car ownership increased, there was little practical need for rickshaws. Today, there are only about twenty pullers, usually stationed at hotels or the beach for short tourist trips or photo opportunities. In 2011, the poor condition of many of the rickshaws and puller attire led to a collaborative project between Durban’s Rickshaw Pullers Association and the staff and students of Workspace, part of the Department of Visual Communication Design at Durban University of Technology, with the support of municipal authorities. This was intended to both provide a facelift for the rickshaws and their position as a unique aspect of local artistry, and to familiarize graphic designers with Zulu design.

Another new direction for traditional arts has opened up with an international interest in Zulu basketry. In the 19th century, plain woven grass baskets gave way to examples with wire ornamentation in brass and copper. Versions decorated with beads, buttons, keys and other materials emerged in the early 20th century, followed by examples made solely from colorful telephone wire. Men make many sizes and shapes of wire baskets, but one of the most popular forms consists of an enlarged and inverted wire imbenge, which has become

© Musée du Quai Branly, 71.1991.189.2.

a shallow basket, rather than a beer pot lid (Fig. 760).

Beading has provided Zulu women with new economic and artistic opportunities. High-end necklaces that mimic the shapes of some traditional jewelry are sold in fashionable shops, their colors and patterns departing from older ornaments. Beaded bands and necklaces for tourists are a frequent market sight (Fig. 761), as are dolls and “love letters.” Some of the latter incorporate the red ribbon symbol that signifies HIV/AIDS awareness, since South Africa has the highest HIV rate in the world,

affecting 7.1 million people. The ribbon even shows up in some three-dimensional work, including a commissioned crucifix (Fig. 762).

Further Reading

Armstrong, Juliet. “Ceremonial Beer Pots and their Uses.” In Benedict Carton, et. al., eds. Zulu Identities: Being Zulu, Past and Present, pp. 414-417. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Armstrong, Juliet and Ian Calder. “Traditional Zulu Pottery.” In Loretta van Schalkwyk, ed. Zulu treasures: of kings and commoners: a celebration of the material culture of Zulu people = Amagugu kaZulu, pp. 107-114. Ulandi and Durban, SA: KwaZulu Museum and Local History Museums, 1996.

Arnoldi, Mary Jo and Christine Mullen Kreamer. Crowning Achievements: African Arts of Dressing the Head. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1995.

Berzock, Kathleen Bickford. For Hearth and Altar: African Ceramics from the Keith Achepohl Collection. New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press for The Art Institute of Chicago, 2005.

Biermann, Barrie. “Indlu: The Domed Dwelling of the Zulu.” In Ed. Paul Oliver. Shelter in Africa, pp. 96-105. London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1971.

Cameron, Elisabeth with a contribution by Doran H. Ross. Isn’t S/he a Doll? Play and Ritual in African Sculpture. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History 1996.

Carton, Benedict; John Laband and Jabulani Sithole, eds. Zulu Identities: Being Zulu, Past and Present. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Connor, Michael. “The 19th Century Nguni Prepuce Cover: A Vanished Aesthetic Locus.” 33rd Annual Meeting of the African Studies Association. Baltimore, 1990. Accessed July 28, 2013, http://www.ezakwantu.com/Gallery_Penis_Cover_Prepuce_Cover.htm.

Conru, Kevin. The Art of Southeast Africa from the Conru Collection. Milan: 5 Continents, 2002.

Dewey, William J. Sleeping Beauties. Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1993.

Douglas Dawson Gallery. Ukhamba: Masterworks of Zulu Potters. Chicago: Douglas Dawson, 2006.

Fowler, Kent D. “Classification and collapse: the ethnohistory of Zulu ceramic use.” Southern African Humanities 18 (2, 2006): 93–117.

Gatfield, Rowan. “Walking with Dignity: The Durban Rickshaw Renovation Project.” Durban, 2012.

de Haas, Mary. “Beer.” In Ubumba: aspects of indigenous ceramics in KwaZulu-Natal, pp. 13-17; 124-129; 141-147. Pietermaritzburg, SA: Tatham Art Gallery, 1998.

Hammond-Tooke, W. D. “Cattle Symbolism in Zulu Culture.” In Benedict Carton, et. al., eds. Zulu Identities: Being Zulu, Past and Present, pp. 62-68. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Hooper, Lindsay. “Domestic Arts: Carved Wooden Objects in the Home.” In Loretta van Schalkwyk, ed. Zulu treasures: of kings and commoners: a celebration of the material culture of Zulu people = Amagugu kaZulu, pp. 73-79. Ulandi and Durban, SA: KwaZulu Museum and Local History Museums, 1996.

Jolles, Frank. “Zulu Beer Vessels.” In Stefan Eisenhofer, ed. Spuren des Regenbogens: Kunst und Leben im südlich Afrika/Tracing the Rainbow: Art and Life in Southern Africa, pp. 306-319. Linz: Arnoldsche/Land Oberosterreich, 2001.

Jolles, Frank. African Dolls: The Dulger-Collection. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2010.

Jolles, Frank. “The origins of the twentieth century Zulu beer vessel styles.” Southern African Humanities 17 (December, 2005): 101–151.

Kennedy, Carolee. The Art and Material Culture of the Zulu-Speaking Peoples. Los Angeles: UCLA Museum of Cultural History, 1978.

Klopper, Sandra. “Kings, commoners and foreigners: artistic production and the consumption of art in the southeast African region.” In Kevin Conru, ed. The Art of Southeast Africa from the Conru Collection, pp. 39-52. Milan: 5 Continents, 2002.

Klopper, Sandra. “Passing things off as Zulu.” In Voice-Overs: Wits writings exploring African artworks, pp. 78-79. Johannesburg: University of the Witswatersrand Art Galleries, 2004.

Klopper, Sandra, Anitra C. E. Nettleton and Terence Pethica. The Art of Southern Africa: The Terence Pethica Collection. Milan: 5 Continents, 2007.

Koopman, Adrian. “Zulu Names.” In Benedict Carton, et. al., eds. Zulu Identities: Being Zulu, Past and Present, pp. 439-448. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Krige, E. J. “Girl’s Puberty Songs and Their Relation to Fertility, Health, Morality, and Religion among the Zulu.” Africa 38 (1968):173-198.

Labelle, Marie-Louise. “Beads of Life: Eastern and Southern African Adornments.” African Arts 38 (1, 2005): 12-35; 93.

Lewin, David. Spirit of Africa: Southern Africa by Design. Gimhae-Si, ROK: Clayarch Gimhae Museum, 2007.

Magwaza, Thenjiwe. “’So That I Will Be a Marriageable Girl’: Umemulo in Contemporary Zulu Society.” In Benedict Carton, et. al., eds. Zulu Identities: Being Zulu, Past and Present, pp. 482-496. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Mayr, Father Fr. “The Zulu Kafirs of Natal.” Anthropos 2 (3, 1907): 392-399.

Mayr, Father Fr. “Zulu Proverbs.” Anthropos 7 (4, 1912): 957-963.

Morris, Jean and Eleanor Preston-Whyte. Speaking with Beads: Zulu Arts from Southern Africa. London: Thames & Hudson, 1994.

Nel, Karel. “Consonant with cattle-culture: the art of the portable,” In Kevin Conru, ed. The Art of Southeast Africa from the Conru Collection, pp. 13-38. Milan: 5 Continents, 2002.

Ngubane, Harriet. “Some Notions of ‘Purity’ and ‘Impurity’ among the Zulu.” Africa 46 (3, 1976): 274-284.

Papin, Robert. “Some Zulu uses for the animal domains: Livestock (imguyo) and game (iziwane).” In Loretta van Schalkwyk, ed. Zulu treasures: of kings and commoners: a celebration of the material culture of Zulu people = Amagugu kaZulu, pp. 183-215. Ulandi and Durban, SA: KwaZulu Museum and Local History Museums, 1996.

Petridis, Constantine. The Art of Daily Life: Portable Objects from Southern Africa. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art/Milan: 5 Continents Editions: 2011.

Poland, Marguerite. “Zulu Cattle: Colour patterns and imagery in the names of Zulu cattle.” In Loretta van Schalkwyk, ed. Zulu Treasures: Of King and Commoners, pp. 35-42. Durban: KwaZulu Cultural Museum and the Local History Museums, 1996.

Proctor, André and Sandra Klopper. “Through the Barrel of a Bead: The Personal and the Political in the Beadwork of the Eastern Cape.” In Ezakwantu: Beadwork from the Eastern Cape, pp. 56-65. Cape Town: National Gallery of South Africa, 1993.

Rankin-Smith, Fiona. “Beauty in the Hard Journey: Defining Trends in Twentieth-century Zulu Art.” In Benedict Carton, et. al., eds. Zulu Identities: Being Zulu, Past and Present, pp. 409-413. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

van Schalkwyk, Loretta, ed. Zulu treasures: of kings and commoners: a celebration of the material culture of Zulu people = Amagugu kaZulu, pp. 73-79. Ulandi and Durban, SA: KwaZulu Museum and Local History Museums, 1996.

Streetton, Jenny. All Fired Up: Conversations between Kiln and Collection. Durban: Durban Art Gallery, 2012.

Winters, Yvonne. “The Secret of Zulu Bead Language and Proportion and Balance of the Zulu Headrest (Isigqiki).” In Benedict Carton, et. al., eds. Zulu Identities: Being Zulu, Past and Present, pp. 418-423. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Wood, Marilee. “Zulu beadwork.” In Loretta van Schalkwyk, ed. Zulu treasures: of kings and commoners: a celebration of the material culture of Zulu people = Amagugu kaZulu, pp. 143-170. Ulandi and Durban, SA: KwaZulu Museum and Local History Museums, 1996.

van Wyk, Gary. “Illuminated signs: Style and Meaning in the Beadwork of the Xhosa- and Zulu-Speaking Peoples.” African Arts 36 (3, 2003): 12-33; 93-94.

van Wyk, Gary. “Pots in Zulu symbolism.” Studio Potter 35 (1, 2006): 26-30.