Chapter 4: The Impact of Religion and Hierarchy on African Art

Chapter 4.5 Art in Small-Scale Communities

Small-scale communities might have had a ruler, but they generally operated as city-states without considerable resources, since their populations were limited. Any taxes would not have been sufficient to import large quantities of the luxury materials that larger societies had, so wood, terracotta, and textiles were thus the standard mediums for artists. The absence of a wealthy court also would have limited the number of artists–they might make household goods for citizens and the occasional mask or figure for individuals or men’s or women’s societies, but a lesser demand for artworks meant that fewer specialists were needed, and those who did exist were often part-time specialists. These artists generally reserved their artistry for the dry season, since they needed to farm to support a family. This sub-chapter will examine the arts of two small-scale groups: the Dan of Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire, and the Igbo of southeastern Nigeria. Both of these groups used masking to bind the community, even though many other art forms existed as well.

The Dan of Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire

The Dan–also known as the Gio or Yakuba/Yakouba–stretch from southwestern Côte d’Ivoire into northeastern Liberia. A Mande-speaking group, they moved into this mountainous region centuries ago, and the difficult terrain has helped to keep most of their agriculturally-based settlements small and independent of federation. A council of elders assists the local ruler, but art is less in the service of courts than it is an expression of spiritual affiliation and resultant personal boosts. Prominence in society emerges from excellence in accomplishment–whether as a farmer, weaver, singer, dancer, or hospitable individual.

The wealthy man dresses well (Fig. 764), in hand-woven cotton robes that today are more likely to bear machine rather than the hand embroidery of the past. In the past, he and his favorites wore brass jewelry cast by a blacksmith (Fig. 765)–but its use was banned in Liberia in the 1930s, ostensibly due to health issues related to chafing, bone damage due to weight, and infections–perhaps excuses to remove impediments to labor. In the past and now, his stature demanded that he host lavish parties. These gatherings might serve as the occasions to

display a wooden portrait of his favorite wife to guests (see Chapter 3.8), or show them a brass figure that demonstrated his largesse as a patron.

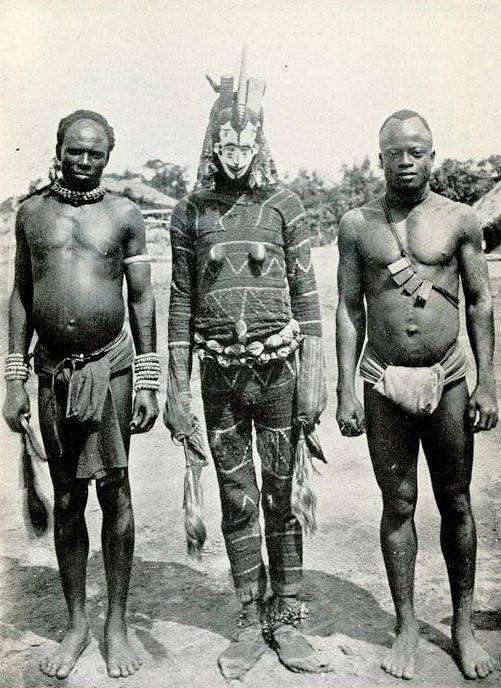

Dan culture concentrates on rice farming and the kola nut trade, but spiritual interactions were once the basis for daily and ceremonial life, as well as societal advancement, beginning with initiation into male and female secret societies. Girls’ initiation into Kong begins with excision; they learn childbirth, household affairs, and the spirits (Ge or Gle; plural Genu) as adolescents. Secret training for boys begins with circumcision in the forest (Figs. 766, 767), and a lengthy subsequent stay independent of their families as they learn the ways of adults and forest spirits. Both genders bond to their agemates through initiation processes that inculcate them through verbal education, esoteric training, spousal management, a trade, and more. teach them about

the Ge. That this education is forest-based is meaningful. Children are warned about the dangers of the forest; it is only through initiation that individuals awaken to the forest’s opportunities: game for the hunter, herbs, roots, and other ingredients for the ritual specialist, and, most of all, the opportunity to meet a forest spirit whose friendship can attract the social spotlight.

While traditional Dan religion honors a High God, he is a distant figure without active worship. Instead, interactions with the supernatural realm are directed toward the Genu forest spirits, who act as intermediaries between this world and the next. Associated with natural landscape features like the mountains that dominate the region, the rainforest, or running water, they will appear in the dreams of the humans they encounter, pleading for corporeality through representation as masquerades. Each Ge has a distinctive personality, and its masquerade will

bear a personal name and an associated dance, music, and lyrics that distinguish it from others–even others in the same classification. The man who enters into such an agreement will commission a wooden mask, assemble the costume elements, and instruct musicians and a dancer regarding the Ge’s performances. Through the admiration and renown the masquerader attracts, both Ge and its “master” are satisfied. Their relationship brings fame and a

The masquerades perform community roles within society; they may function as entertainers, cautionary examples of bad

behavior, fire marshals, or have other responsibilities. These are not necessarily fixed. Through dream conversations with their masters, the Genu may alter their roles and request physical changes to mask or costume to facilitate these shifts.

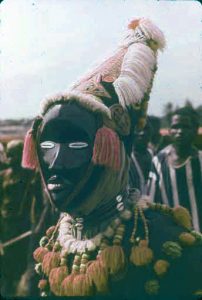

Some of the most common masqueraders are entertainers who dance, take a jokester role, or are singers. Those named Dean Ge/Gle (Fig. 768) perform at public functions, but also participate in the initiation camp’s activities, bringing the isolated boys food from their mothers, thus assuming a comforting, encouraging, maternal role. Although spirits are genderless, this type of masquerade has a feminine appearance, emphasizing ideal traits of beauty, such as narrow slitted eyes, a pointed chin, and an overall delicacy (Fig. 769).

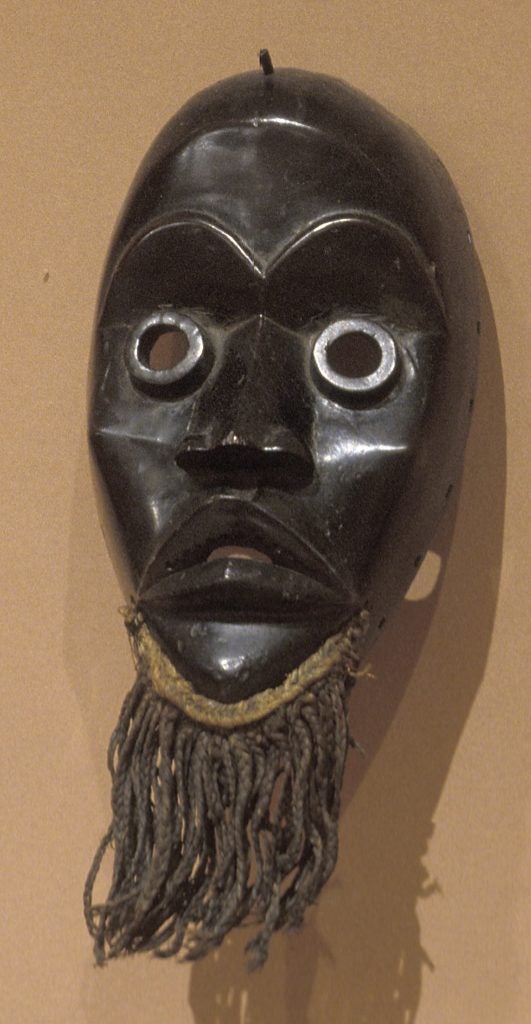

Those named Dean Ge/Gle (Fig. 768) perform at public functions, but also participate in the initiation camp’s activities, bringing the isolated boys food from their mothers, thus assuming a comforting, encouraging, maternal role. Although spirits are genderless, masquerades like this have a feminine appearance, emphasizing ideal traits of beauty, such as narrow slitted eyes, a pointed chin, and an overall delicacy. They usually have a glossy black surface that recalls healthy, well-groomed skin, a nose that fits within triangular parameters, and an oversized mouth that is frequently downturned. Many examples include a raised vertical line that bisects the forehead–this refers to a former type of regional facial scarification for women. The face is often keeled at the eyes, with both forehead and chin projecting forward (Fig. 769). The performer’s attire includes a voluminous raffia skirt, as most Dan masqueraders wear, recalling the wilderness where the spirits originally manifested (Fig. 770). Some examples

have cowrie shells added to the headdress, a reference to pre-colonial currency that honors the spirit through monetary gifts, as do beads. Female singing spirits often wear tall hats (Fig. 771), and many feminine-style masks originally had elaborate hairstyles made from fiber or actual hair, as well as carved or aluminum teeth, references to archaic female cosmetic modifications.

Masks with round eyes, whether projecting or not, are considered manifestations of “male” spirits. Less significant–but no less popular–examples include runners, who participate in races with human competitors (Fig. 772), as well as the similar-looking firewatchers (Fig. 773), who ensure cooking fires are extinguished during the dry season, when a spark might set a roof ablaze.

Jokesters, skit performers/dancers (Fig. 774), war leaders, dancers, and singers constitute other examples of excellence from the spirit world, as do stiltwalking ge (video below). While most of these take abstracted human forms, two common types incorporate animal features. “Male” singing masks often incorporate bird-like beaks (Fig. 775), while kagle–a mask whose antisocial behavior teaches good behavior by aggressively breaking its rules–is meant to represent a chimpanzee (Fig. 776). The masquerader throws sticks at observers, chases livestock, and incites crowd members by trying to interfere with their clothing.

Any mask can be promoted to a different function, however, so its appearance might only indicate its initial usage. A powerful mask may remain unused in a family until the spirit feels a kinship with a male that enables a partnership to reinstate it. The supreme masqueraders are those who represent town quarters or are judges and peacemakers. Their costumes often change upon promotion or medicinal materials may be added to their headpieces and dress.

Further Reading

Fischer, Eberhard. “Dan Forest Spirits.” African Arts 11 (2, 1978): 16-23; 91.

Fischer, Eberhard and Hans Himmelheber. The Arts of the Dan in West Africa. Zurich: Museum Rietberg, Zurich, 1984.

Grootaers, Jan-Lodewijk and Alexander Bortolot, eds. Visions from the Forests: The Art of Liberia and Sierra Leone. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014.

Reed, Daniel B. Dan Ge Performance: Masks and Music in Contemporary Côte d’Ivoire. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2003.

Reed, Daniel B. “‘The Ge is in the Church’ and ‘Our Parents are Playing Muslim’: Performance, Identity, and Resistance among the Dan in Postcolonial Côte d’Ivoire.” Ethnomusicology 49 (3, 2005): 347-367.

The Igbo of southeastern Nigeria

The Igbo are a densely-populated group of southeastern Nigerian peoples who, before colonization, did not regard themselves as belonging to a single ethnicity. Most lived in republican communities where all freeborn adult men could partake in decision-making, although some–titleholders whose

wealth and achievements had advanced them–had more sway than others. A relatively small number of Igbo lived in kingdoms based on the Benin model. Most of these were west of the Niger River and had been part of the Benin Empire at one point or another, adopting its regalia and hierarchy. Most Igbo were farmers in the past, and many still are. The fractiousness of Igboland in past centuries meant that one community’s contact with another was limited, and in some cases restricted to the frequent raids and skirmishes rival communities had with one another. Allies and trading partners existed, and the arts of those Igbo living near other ethnicities were often more impacted by these foreign traditions than by those of other Igbos whose territories might be off-limits. These divisions led to arts that are less cohesive than those of comparably-sized ethnic groups. While certain art forms–men’s personal shrines (ikenga), spirit masquerades, and community ancestor figures are found throughout most of Igboland, their style varies considerably from place to place. Some object types occur only in a distinctly limited area.

British occupation and subsequent independence provided the Igbo with a more nationalistic bond as they grew aware of the strength to be had in numbers. In 1967 the Igbo seceded from Nigeria, declaring the independent nation of Biafra and prompting the Nigerian Civil War, which ended with their defeat and reunification in early 1970. The war had a significant impact on area infrastructure, social mores, and many aspects of culture, including art. While it raged, many shrines and households were stripped of sculpture by both invading soldiers and those Igbo who were trying to survive by selling sculpture to buyers who took the pieces overseas. Afterward, their replacement was not an economic priority. This depredation coincided with the continued blossoming of Christianity, particularly Catholicism (Fig. 777); in 1965, Francis Arinze became the world’s youngest Catholic bishop, rising to the rank of Cardinal in 1985. While traditional religion and associated arts have not disappeared completely in Igbo territory, these practices have certainly diminished. Many masquerades that used to be sacred in their orientation are now directed toward entertainment, particularly during the celebration of Christmas holidays.

Igbo-Ukwu

Out knowledge of Igbo art before the late 19th century is spotty. Oral histories collected from the bulk of Igbo communities reiterate their political independence and sense of male egalitarianism. Everyday culture still stresses a drive toward male achievement and aggression culminating in titles that involve status display. How old are these concepts and expression? Like most parts of Africa, we’re uncertain because of a lack of tangible evidence. However, an accidental discovery in 1938 by a farmer in the small village of Igbo-Ukwu led to a series of archaeological discoveries that both reinforced the longevity of certain cultural practices and seemed to counter them (Fig. 778).

The farmer found a number of bronze items, keeping some and giving others to his neighbors. When the British District Commissioner heard about the finds, he retrieved many of the pieces, but it took two decades (World War II having intervened) before the British archaeologist Thurstan Shaw was sent to excavate, just before Nigeria’s independence. Except for the farmer’s initial accidental finds, Igbo-Ukwu is one of the relatively few African excavations that was not conducted on an emergency basis or with looting as a major concern.

The finds were astounding. Three sub-sites were located, named for the three brothers who occupied the land. Igbo Isaiah (Fig. 779) was a true treasure trove. Its contents suggest it was a shrine storage area, one filled with ritual vessels of terracotta and bronze (Fig. 780), as well as hip pendants, jewelry, and staff ornaments. It appeared to have been an open-sided roofed structure that had been abandoned and undisturbed, probably due to abandonment.

Igbo Jonah was a pit that included broken items as well as some bronze pot stands and staff heads. It seemed to have been made intentionally for disposal.

Igbo Richard was an archaeologist’s high point–the burial site of a high-status individual. The grave had been dug deep, presumably lined with carved wood, and the corpse was

placed in a seated, upright position (Fig. 781). The remains of three ivory tusks were found, as well as a copper tiara crown and pectoral, a cast bronze leopard skull, a copper fan handle, jewelry, the cast bronze handle of what may have been a flywhisk, wrought in the shape of a horse

and rider, and pottery. The grave had then been roofed with wooden planks, and the remains of at least five sacrificial victims (human sacrifice in Africa was uncommon, reserved only for those of high rank), were found over it.

The finds in all three sub-sites were significant for multiple reasons. Technologically speaking, they are the oldest examples of lost-wax (although some researchers believe rubber may have been used instead of wax) bronzecasting known in West, Central, and South Africa; only some works in northeast and north Africa are older. They certainly do not mark the earliest stages of casting, for their ornament and technique speak to skills that are highly developed. They display an astonishing interest in decorating surfaces–even small ones–with a variety of geometric patterns, resulting in ornate surfaces marked with concentric circles, spirals, triangles, granulated lines, and many other designs. A variety of interlace patterns, many known in the Benin Kingdom and among the Yoruba in later centuries, also occur. These are often thought to have been derived from the Muslim Hausa, but Igbo-Ukwu predates the Islamicization of the Hausa.

Many of the items in the shrine storage area are skeuomorphs, imitations of objects normally made of other materials, such as bronze versions of bound terracotta pots, bronze snail shells (there are at least three; they may have served to sprinkle palm wine or were used as vessels), and bronze calabashes (Figs. 778 and 782). Metal pendants–worn at the hip in later societies

at Ife and Benin–appear here to have been made in pairs, and include a variety of animal forms, including birds, rams, leopards, and elephants, of which four were found (Fig. 783). Though many of these were small, one of a pair of bird-with-eggs pendants was found with long attached beaded chains and crotals (small clapperless bells or jangling bits). These suggest placement at the hip, where the hanging elements could both swing and announce the presence of the wearer through sound.

Insect representations are rare in African art, but beetles, spiders, grasshoppers, and flies occur in

Igbo-Ukwu art. Animal representations besides those on the pendants and equestrian hilt include numerous depictions of snakes, many with eggs in their mouths, monkeys, mudfish, frogs, and a pangolin. There are, however, very few representations of human beings. These are restricted to the male equestrian bronze, a standing male and female on a bronze pot stand, a Janus-headed ornament, and the heads of men on two matching bronze pendants (Figs 784, 785), as well as relief images of heads on a series of bronze staff ornaments.

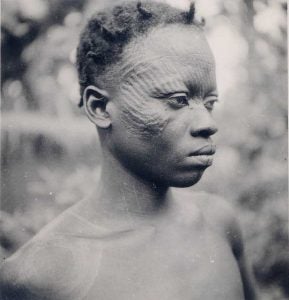

These heads–as well as that of the equestrian, the female figure on the potstand, and the heads on staffs–include a series of diagonal marks on the forehead and cheeks. These correspond to ichi marks, a special body modification that persisted into the 20th century as a badge of distinction for those men who had taken the highest title possible (Fig. 786).

Two particularly surprising and related aspects emerged at Igbo-Ukwu: the apparent existence of a significant ruler in an area without a history of monarchs and the accrued wealth evident in the numerous objects made from precious metals and decorated with imported beads–over 100,000 glass and stone beads were found at Igbo Richard alone, while more than 63,000 others ornamented pendants and staff heads at Igbo Isaiah (Fig. 787). Looking at the more recent history of this Igbo region, the general conclusion is that the entombed figure was the Eze Nri, a priest-leader rather than a secular king. The Nri priesthood that he headed had the power to remove spiritual pollution that affected land and crops, and Nri priests moved freely through warring Igbo communities to perform these ritual duties into the early 20th century, and staffs served as one of their badges of authority. The numerous staff heads and shaft ornaments found at Igbo-Ukwu may have been used in this way (Fig. 788).

The priestly purification was a transaction that required payment, and the accrued tribute apparently allowed for the purchase of beads through a long-distance trade network, perhaps in exchange for ivory or for the kola nuts Saharan travelers desired. The metals used were initially thought to have been imported from across the Sahara as well, but worked copper pits and lead sources have been located in Igboland about 62 miles east of Igbo-Ukwu, with tin extraction possible in central Nigeria at a far greater distance. As for the location of the site, the Eze Nri headship split centuries ago; that is, one Eze Nri is located at Nri, just over ten miles from Igbo-Ukwu, while another was based at Oreri, to the immediate north of Igbo-Ukwu. Elders at Oreri stated that Igbo-Ukwu had formerly been part of their territory, and Igbo-Ukwu elders concurred, saying they had seized the land through battle. As to why Igbo-Ukwu, if it was the burial place of an Eze Nri and site of his sacred regalia, may have been abandoned and forgotten, we cannot be certain.

The pieces unearthed at Igbo-Ukwu demonstrate how tentative our knowledge about pre-19th-century art remains in the absence of more archaeology. It also raises as yet unanswerable questions that are both technical and historical: where did West African lost wax casting originate? How old is the tradition? Was it independently developed? What relationship did Igbo-Ukwu have with neighboring states known for their later casting, such as the relatively nearby Benin Kingdom?

Many centuries of unknown art intervened between the time of Igbo-Ukwu and the colonial presence of the late 19th century, but because the bulk of it was made from wood–subject to attack by termites–we do not know what it looked like. Likewise, we cannot be sure that the Igbo of the 8th-10th centuries made masks or other wooden object types known from more recent times, because they too would not have survived. Iron and other metalworking traditions are still strong in the Awka area, not far from Igbo-Ukwu, which is also a major carving center.

The Ikenga

Until recent decades, many ambitious Igbo men owned personal altars to accomplishment known as ikenga (Fig. 789). The ikenga was a major art form throughout much of Igbo territory, particularly in the area once under Nri’s sway, with the exclusion of some of the eastern and southeastern areas. Few if any seem to be made now because of Christianity’s impact. This object is a wooden shrine made to honor a man’s right arm (ike=power; right hand = “aka ikenga” or “the ikenga hand”) and was usually a male personal possession, kept in the bedroom and sacrificed to, the

altar’s intent being a maximization of success through one’s own efforts. The ikenga focuses on an important Igbo concept–personal achievement rather than fate. Its association with the right arm/hand has to do with the thought that it is one’s right arm than expends all the effort needed for success, whether it be in wielding a hoe or a weapon or even a pen–children whose natural inclination is to be left-handed are forced to change their usage because the left hand is considered negative and associated with pollution. Since in the past young men had to constantly be alert for war raids or ready to carry them out, success and advancement were often linked to battle valor (Fig. 790). Typical of warrior examples, this figure holds a weapon in one hand and a severed enemy head in the other, speaking to his success. Large horns represent those of a ram, whether semi-straight, as they are in this example, or curved, for the ram’s horns are allusions to male aggression,

determination, and power. He wears a loincloth that reveals his penis, for the link between successful manhood in cultural and physical terms are alluded to in the male joking exchange, “Is your ikenga standing straight today?” a phrase that can also refer to good fortune. Depending on the region they were from, their faces could be more or less naturalistic, sometimes stylized in the form of the maiden spirit masks (Figs. 804, 806), since young men served as the masqueraders.

The figure is seated on a chieftaincy stool (Fig. 791), for achievements in battle were linked to advancement in the title-taking system. Despite Igbo egalitarianism, men of wealth and/or achievement can socially advance by assuming different levels of titles, each with attached fees and privileges. The highest title is that of ọzọ, which commands widespread respect: “Ichi ọzọ bu maka ndi ogadagidi” (“Taking the ọzọ title is something meant for the rich”). Women also take titles, the highest marked by wide, plain ivory anklets and bracelets (odu), and artwork indicates titled men once wore these as well. The ọzọ title’s practical functions are as a gateway to influence, political activities, and societal respect, but in its essence it is a kind of ancestral priesthood, and personal purification is a requirement. As such, whiteness (of clothing, for example, or ivory anklets and armlets) is a hallmark of participants.

Other personal ikenga stressed the titleholder basking in the fullness of achievement by stressing one or another form of title stool, as well as the staff and/or elephant’s tusk that served as badges of office; a pipe can sometimes be seen in the figure’s mouth. These ikenga frequently bear the

ichi marks of the highest title to reinforce the owner’s aspirations. Although ikenga were often figurative, they had considerable formal variety. Even the more abstract examples (Fig. 792) usually included a stool form and horns, the former a reference to either the abovementioned titled man’s stool or, if spindle-shaped, to the okposi, a wooden object that “seats” the ancestors.

Some ikenga are larger than most, suggesting a male age-grade commissioned it for joint use, an exclamation of the members’ solidarity and united drive for legendary success (Fig. 793). This example served as both altar and display piece. Its superstructure includes references to humans, leopards, and other horned animals, but this complexity is atypical of ikenga. Its forceful, bristling character is more akin to male spirit masks (mgbedike; see Figs. 800, 801), which embody the assertive, powerful, and dangerous forces of mystical and physical strength. More characteristic are the leadership traits the figure itself displays; while many ikenga depict warriors with weapon and enemy head or men smoking a pipe, this sculpture emphasizes the status of the titled men as an aspiration for an age set. Markers include a backed stool (the back a colonial innovation in imitation of European chairs), ichi forehead scarifications, the titleholder’s iron staff in his right hand, used to serve the ancestors in sacrifice, and an ivory trumpet in his left. The trumpet was a key piece of ọzọ regalia, and some

titleholders own multiple examples. Their ivory signals expense and respect, but their whiteness also underlines the concept of purity so critical to the title. The figure’s chest and upper arm markings may indicate a kind of armor fashioned from nutshells that certain warriors once wore.

Alusi Figures

Igbo traditional religion has a High God, known as Chukwu or Chineke, as well as lesser deities who are closer to human beings, such as Ala, goddess of the earth, Amadioha, god of thunder and lightning,

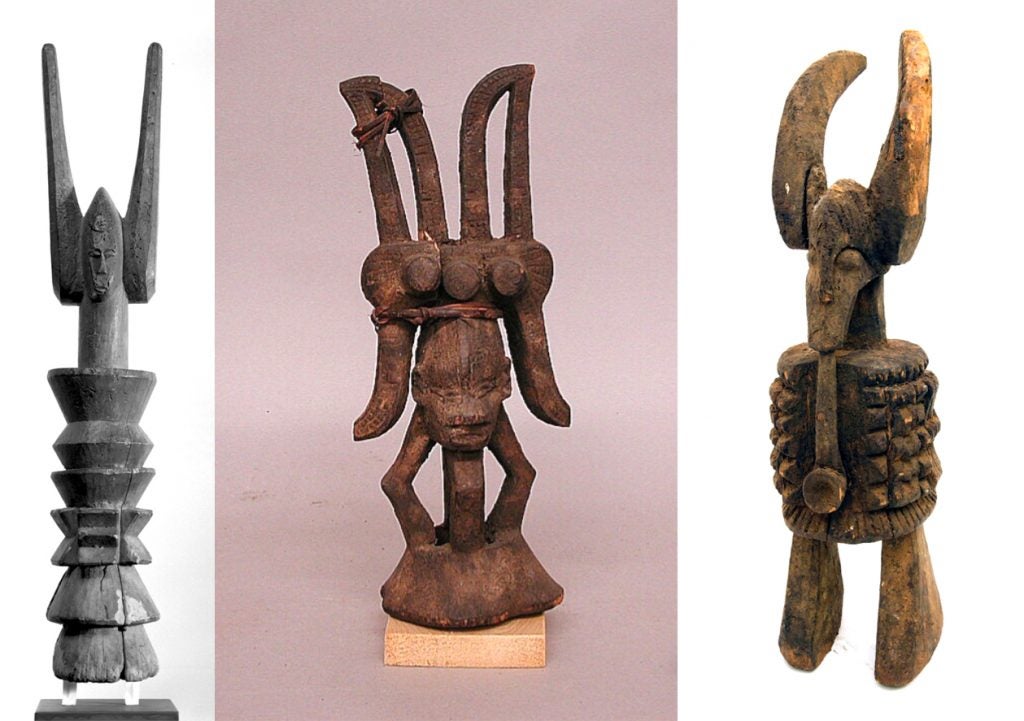

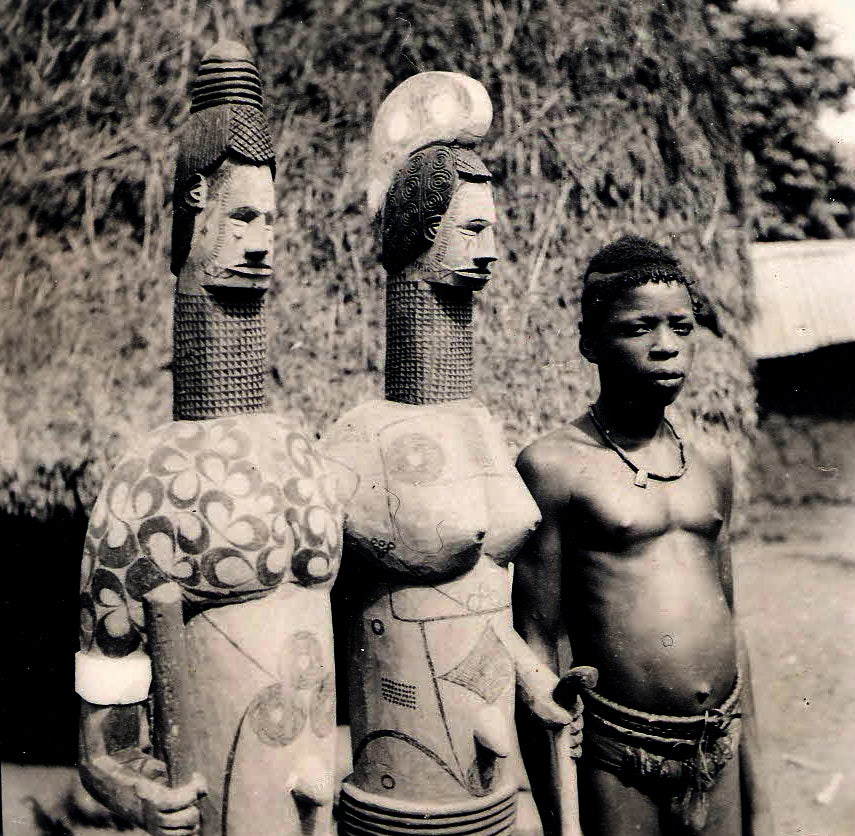

and others. Ancestors play an important spiritual role as well. More localized deities known as alusi are the personified founders of communities, their shrines having priesthoods and acting as the site of offerings and celebrations. Many alusi are manifested by large–sometimes life-size–columnar wooden sculptural ensembles that are amongst the tallest of carved African figures (Figs. 794, 795). They featurie the tutelary deity, his wives, children, and followers; up to twenty figures have been documented in some cases.

Many alusi bear uli body painting created and renewed by women annually (Fig. 796), while some bear ichi titleholders’ forehead scarification (Fig. 797). Real cloth wrappers are sometimes tied to the works (Fig. 798). Alusi bodies tend to have more natural proportions than those of the ikenga, though usually with thick columnar necks. Their standard pose shows standing figures, arms bent at the elbow, hands extended, a gesture of receiving, blessing, and beneficence.

The figures were usually kept in centralized shrines and brought out for annual festival display, but many such shrines were raided during the Nigerian Civil War, dispersing their sculptures throughout the world. Some shrines, however, do remain active.

Masquerades: Beautiful Maidens and Bestial Males

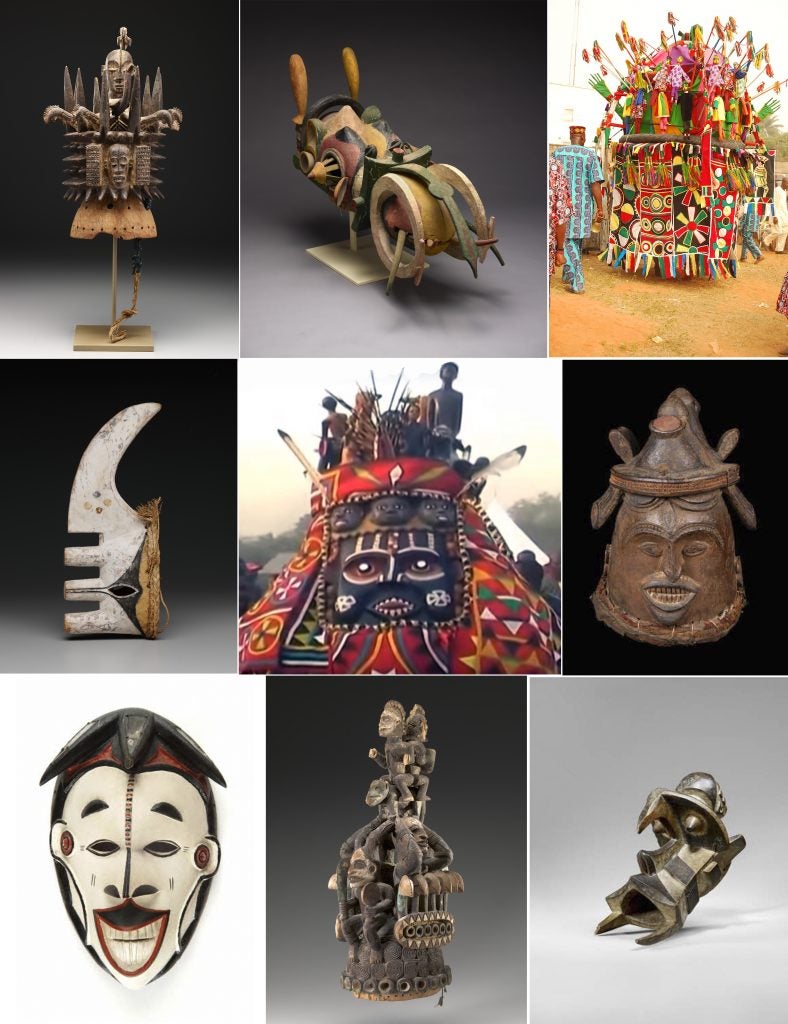

Masquerades of various types occur throughout Igboland, but the northern Igbo masquerades of maiden spirits and fierce males are among the best known. In the areas where these are performed, boys are initiated into the masking society when they are between 8 and 10 years old, and learn its secrets. Women are complicit in expressing their ignorance of such secrets, professing belief that masqueraders come from the spirit world to interact with human beings. Within this area are a slew of mask types, but this discussion will center on two–light-colored female spirit masks and darkened, animal-like male spirit masks–because this gender opposition can be found in other Igbo masquerades as well as among

Charles B. Benenson, B.A. 1933. Public domain.

some of their neighbors, and recalls gender stereotypes and how these are promulgated within a society. All who dance these are male.

Male spirit masquerades (often called mgbedike) are performed by middle-aged or elder men (Figs. 799, 800, 801). While they bear some human features, their emphasis is on power–both physical and mystical–and they reference the world of the bush and medicines through costumes that incorporate or imitate bush materials. Their masks are blackened, often encrusted with sacrificial materials or mysterious excrescences. Facial features may be symmetrical, but frequently include mismatched eyes, a twisted mouth, or a nose turned awry. Horns and other jagged materials often protrude from the surface, and the oversized mouth is filled with huge canine teeth. These masks bear personal names that translate to descriptors like “Tough” or “Bucket of Blood,” names meant to inspire fear. Their dance involves stamping and rushing at the audience; they sometimes carry weapons and have to be restrained from lashing out at spectators. Generally speaking, few of these perform at a given celebration, the power evidenced by their anti-aesthetic requiring little reinforcement.

Female spirit masks (agbogho mmuo), however, evidence cultural values associated with their sex. If men are powerful forces of nature, women are civilizers. Their costumes, meant to signify nude female bodies (Fig. 802) covered with uli patterns (Fig. 803), are made from cloth, a cultural product. Maiden spirit masks emerge in a bevy, and are popular for their graceful movements and the power of their beauty. Their faces tend to be long with similarly long, narrow, sharp noses. Their faces are whitened–an association with the positive aspects of the spirit world–but their features are human, their hair or headdresses ornate in the style of the fashionable girl seeking a marriage partner. These hairstyles often mimic the elaborate coiffures popular at the turn of the 20th century (Fig. 804) that encompassed coils of hair fixed with oil, charcoal, and clay (Fig. 805), crests that incorporated mirrors and combs, or other variations. Some examples include ichi marks (Fig. 806). Although some examples are straightforward masks (perhaps ornamented with cloth and yarn superstructures), many are a combination of a face and helmet mask (Fig. 807), allowing them to be more firmly anchored to the performer.

Both maiden spirit masquerades and mgbedike usually appear in the dry season, when agricultural labors are at their nadir. although they also perform at the funerals of prominent elders. Traditionally, the two masquerades never perform at the same time, since their appeal is oppositional. In that, they mimic what was standard social behavior through most of the 20th century, where males and females led separate social lives. Even in decades past, much of their dance was considered entertaining to both the living and the ancestors, but they also reinforced cultural values relating to gender norms for desirable behavior, even if in exaggerated form.

While these masquerades still dance, their context is even more entertainment-oriented than it once was. Scheduling now takes place according to a liturgical rather than an agricultural calendar, and venues such as stadiums and parade grounds provide another conceptual shift. Nonetheless, the occasions provide a visceral sense of excitement paired with age grade unity and male solidarity.

Some more recent masks remain fairly close to older models (Fig. 808), but others conform to new forms of beauty that do not relate to archaic hairstyles, facial scarifications, or uli-painted bodies. Mgbedike have also adapted, sometimes with shifts that seem drawn from Nigerian horror programs (Figs. 809; 810).

Maiden and male spirit masks on the northern Igbo model make up only a fraction of Igbo masquerades, past and present. Some have wooden face masks, others are entirely made from cloth or fiber, many have accoutrements created with yarn, tassels, stuffed animals, and other animals. This variety is due in part to the historic system of semi-isolated independent city-states that kept nationalism local. Even a cursory look at other Igbo masquerades (Fig. xxx) reveals a dizzying assortment of masquerade types.

Maiden and male spirit masks on the northern Igbo model make up only a fraction of Igbo masquerades, past and present. Some have wooden face masks, others are entirely made from cloth or fiber (Fig. 811), many have accoutrements created with yarn, tassels, stuffed animals, and other animals. This variety is due in part to the historic system of semi-isolated independent city-states that kept nationalism local. Even a cursory look at other Igbo masquerades (Fig. 812) reveals a dizzying assortment of masquerade types.

Further Reading

Afigbo, Adiele Eberechukwu. “Ikenga: the state of our knowledge.” In Stefan Eisenhofer, ed. Kulte, Künstler, Könige in Afrika: Tradition und Moderne in Südnigeria, pp. 349-359; 401-402. Linz: Oberosterreichisches Landesmuseum, 1997.

Aniakor, Chike Cyril. “Female imagery and presence in Igbo arts: the example of Igbo maiden spirit masking: a choreographic/performative presentation of the Igbo ideals of feminine beauty.” Baessler-Archiv, n.f. 43 (1, 1995): 67-88.

Bentor, Eli. “Life as an artistic process: Igbo ikenga and ofo.” African Arts 21 (2, 1988): 66-71; 94.

Bentor, Eli. “Masquerade politics in contemporary southeastern Nigeria.” African Arts 41 (4, 2008): 32-43.

Boston, J. S. “Some northern Ibo masqueraders.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 90 (1, 1960): 54-65, plates I-II.

Cole, Herbert M. Mbari, art and life among the Owerri Igbo. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1982.

Cole, Herbert M. and Chike Aniakor. Igbo arts: community and cosmos. Los Angeles: UCLA Museum of Cultural History, 1984.

Craddock, Paul T., et. al. “Metal sources and the bronzes from Igbo-Ukwu, Nigeria.” Journal of field archaeology 24 (4, 1997): 405–429.

Gore, Charles D. “‘“Burn the mmonwu’: contradictions and contestations in masquerade performance in Uga, Anambra State in southeastern Nigeria.” African Arts 41 (4, 2008): 60-73.

Hufbauer, Benjamin and Bess Reed. “Adamma: a contemporary Igbo maiden spirit.” African Arts 36 (3, 2003): 56-65; 94-95.

Neaher, Nancy C. “Igbo Carved Doors.” African Arts 15 (1, 1981): 49-55; 88.

Ottenberg, Simon. Igbo art and culture, and other essays. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2006.

Ottenberg, Simon. Masked rituals of Afikpo, the context of an African art. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1975.

Shaw, Thurstan. Igbo-Ukwu: an account of archaeological discoveries in eastern Nigeria. London: Faber for the Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan, 1970.