Chapter 3. Project Initiation

3.3 Organizational Dimensions and the Structure

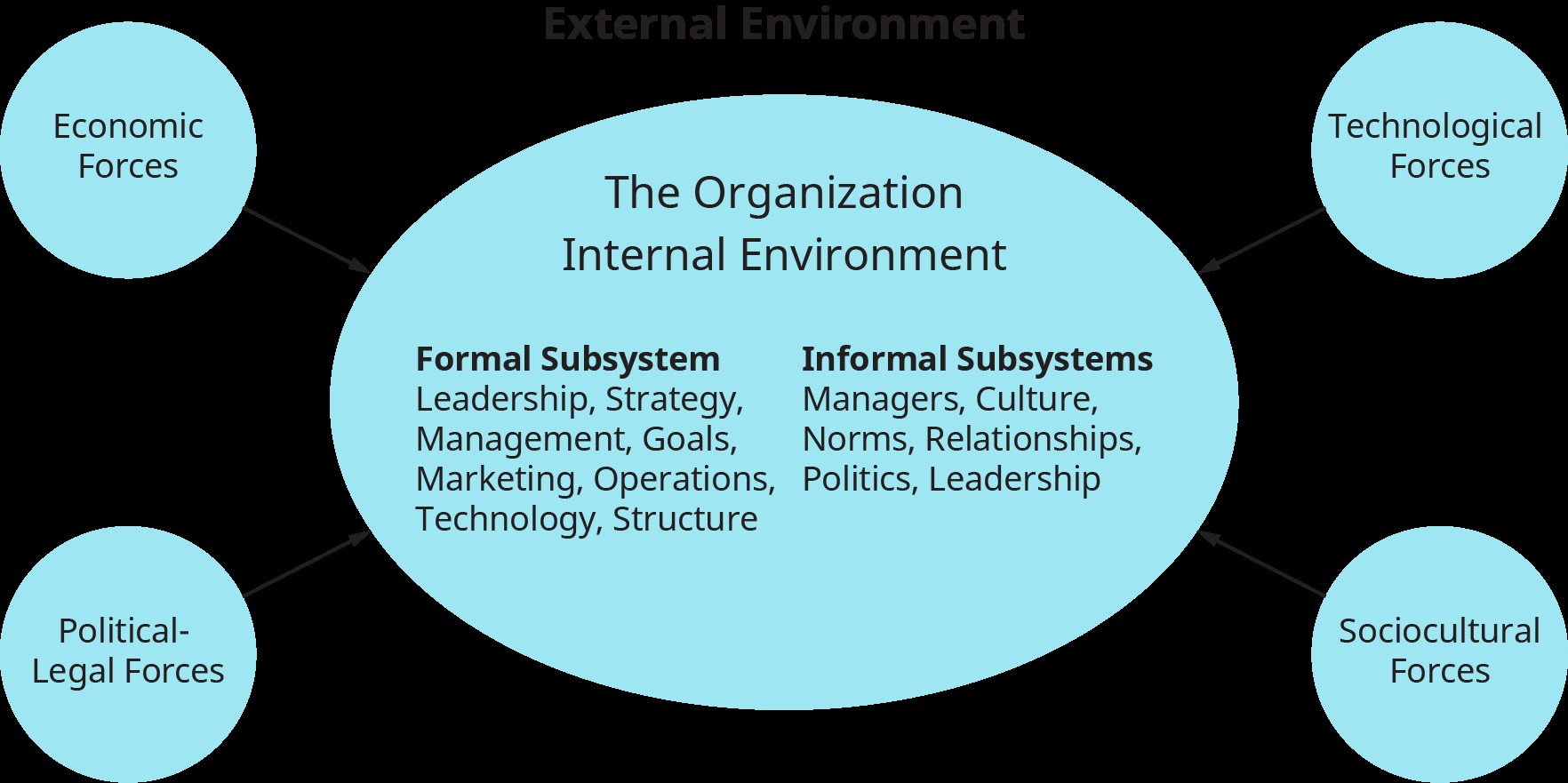

Organizations have formal and informal subsystems that affect everything from big-picture strategic planning and execution to daily operations. Figure 3.3.1 shows internal organizational dimensions. Formal subsystems include leadership, strategy, management, goals, marketing, operations, technology, and structure. Informal subsystems comprise culture, norms, relationships, politics, and leadership skills. Understanding organizational dimensions – and how projects fit within them – gives project managers insights into managing projects more effectively and efficiently.

3.3.1 Formal Subsystem

An organization’s formal subsystems govern how various tasks are divided, resources are deployed, and how units/departments are coordinated. An organizational structure includes a set of formal tasks assigned to employees and departments, a formal reporting relationship, and a design to ensure effective coordination of employees across departments/units with the help of authority, reliability, responsibility, and accountability, which are fundamental to developing organizational structures and workflow based on their clear understanding by all employees. In short, an organizational structure is a system of task and reporting relationships that control and motivate colleagues to achieve organizational goals. In discussing organizational structure, the following principles are important:

- Authority is the ability to make decisions, issue orders, and allocate resources to achieve desired outcomes. This power is granted to individuals (possibly by the position) so that they can make full decisions.

- Reliability is the degree to which the project team member can be dependent to ensure the project’s success with a sound and consistent effort.

- Responsibility is an obligation incurred by individuals in their roles in the formal organization to perform assignments effectively or to work on the project’s success with or without guidance or authorization.

- Accountability refers to how an individual or project team is answerable to the project stakeholders and provides visible evidence of action.

Authority and responsibility can be delegated to lower levels in the organization, whereas accountability usually rests with an individual at a higher level.

An organizational structure outlines the various roles within an organization, which positions report to specific individuals or departments, and how an organization segments its operations into discrete departments. An organizational structure is an arrangement of positions that is most appropriate for the company at a specific point in time. Given the rapidly changing environment in which organizations operate, a structure that works today might be outdated tomorrow. That’s why we often hear about organizations restructuring—altering existing organizational structures to become more competitive/efficient once conditions have changed.

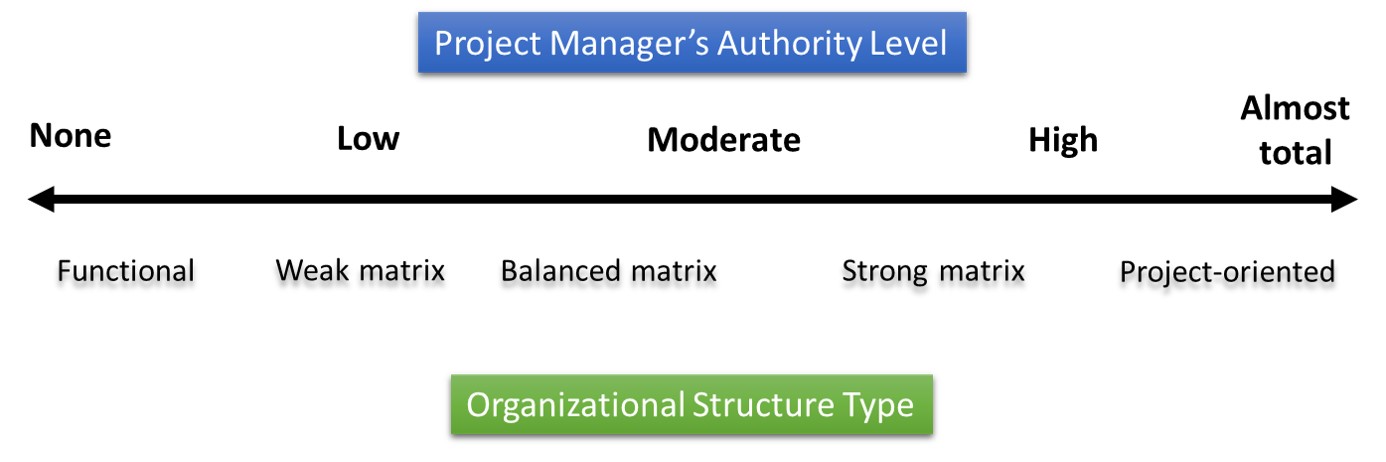

Organizational structures can be categorized as a spectrum of a project manager’s authority. This spectrum includes three main types as below:

- Functional (Centralized)

- Matrix

- Project-oriented / Projectized

3.3.1.1 Functional (Centralized) Organizational Structure

As illustrated in Figure 3.3.2, the project manager’s authority is minimal in a functional organization, whereas it is high to almost total in a project-oriented organization. However, each organization type has advantages and disadvantages, and some organizations can even be a mix of multiple types.

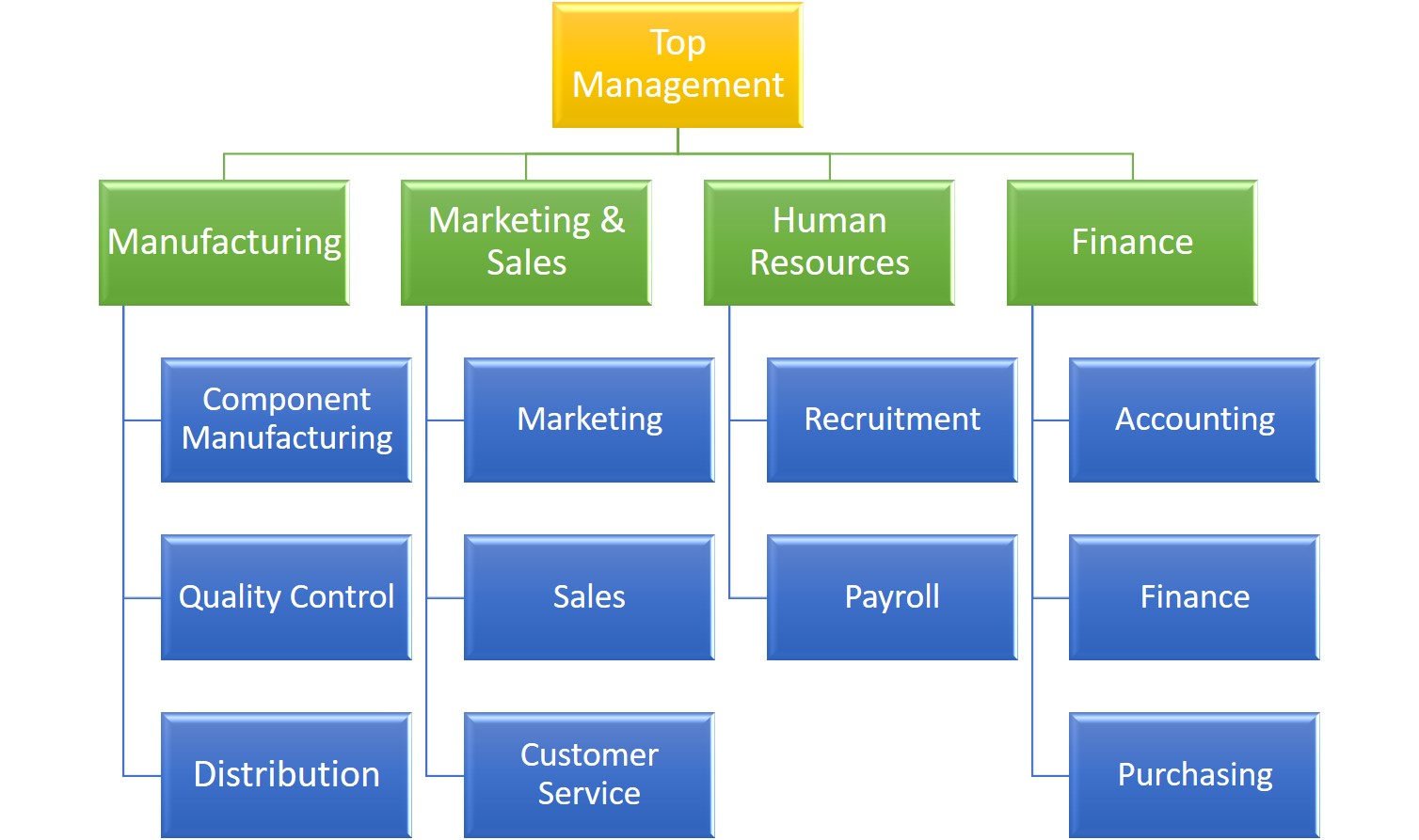

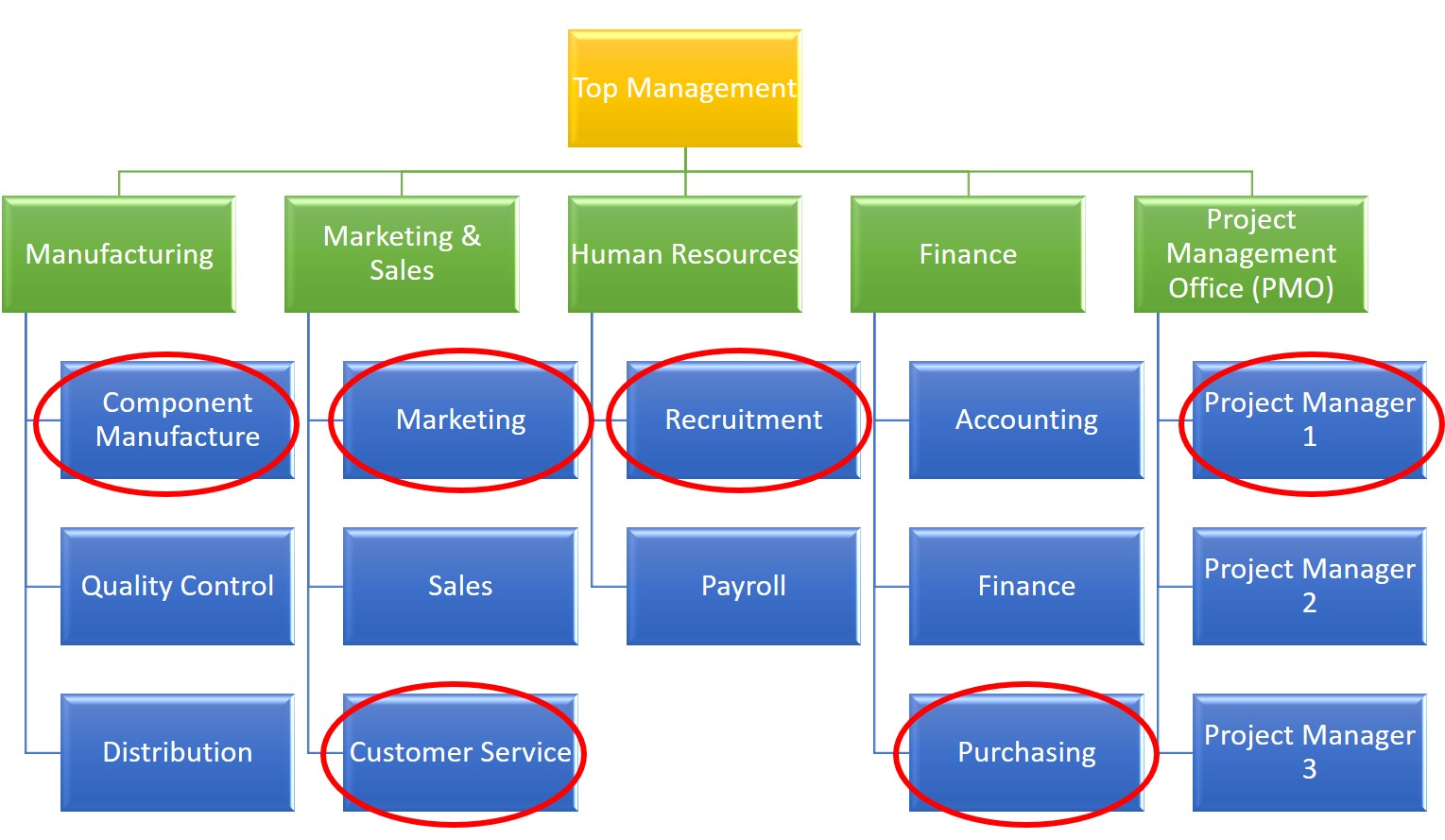

A functional organization has workgroups arranged according to the tasks and jobs performed by specialized departments such as manufacturing, marketing and sales, human resources, and finance, as seen in Figure 3.3.3. Since there is no project management department or office, a project manager or a coordinator is generally selected from the department primarily responsible for conducting a project. However, this person may not have a designated project manager or coordinator role, and their service in this role is often temporary until the project is completed. This department is generally the main beneficiary of the project, or it is the implementing department. For example, if the project’s goal is to improve customer service, a project manager can be selected from among senior or experienced employees, who is also considered as a subject matter expert in the topic of the project, from the “Customer Service” division under the “Marketing & Sales” department. This person may not work full time as a project manager as they may still carry out the routine tasks of their division and department. Additionally, this project manager would be under the supervision of the “Marketing & Sales” department manager. When they need human and other resources, they may be unable to obtain them directly. Still, they should negotiate with their manager (Marketing & Sales department in our case) and other department managers (e.g., Manufacturing, Finance). Thus, the project budget is managed by the functional manager, not the project manager. Moreover, the project team may not have administrative staff. Therefore, the project manager may use their department’s administrative staff part-time. The main advantage of this organization type is that the project manager can acquire qualified and experienced human resources from other functional departments.

3.3.1.2 Matrix Organizational Structure

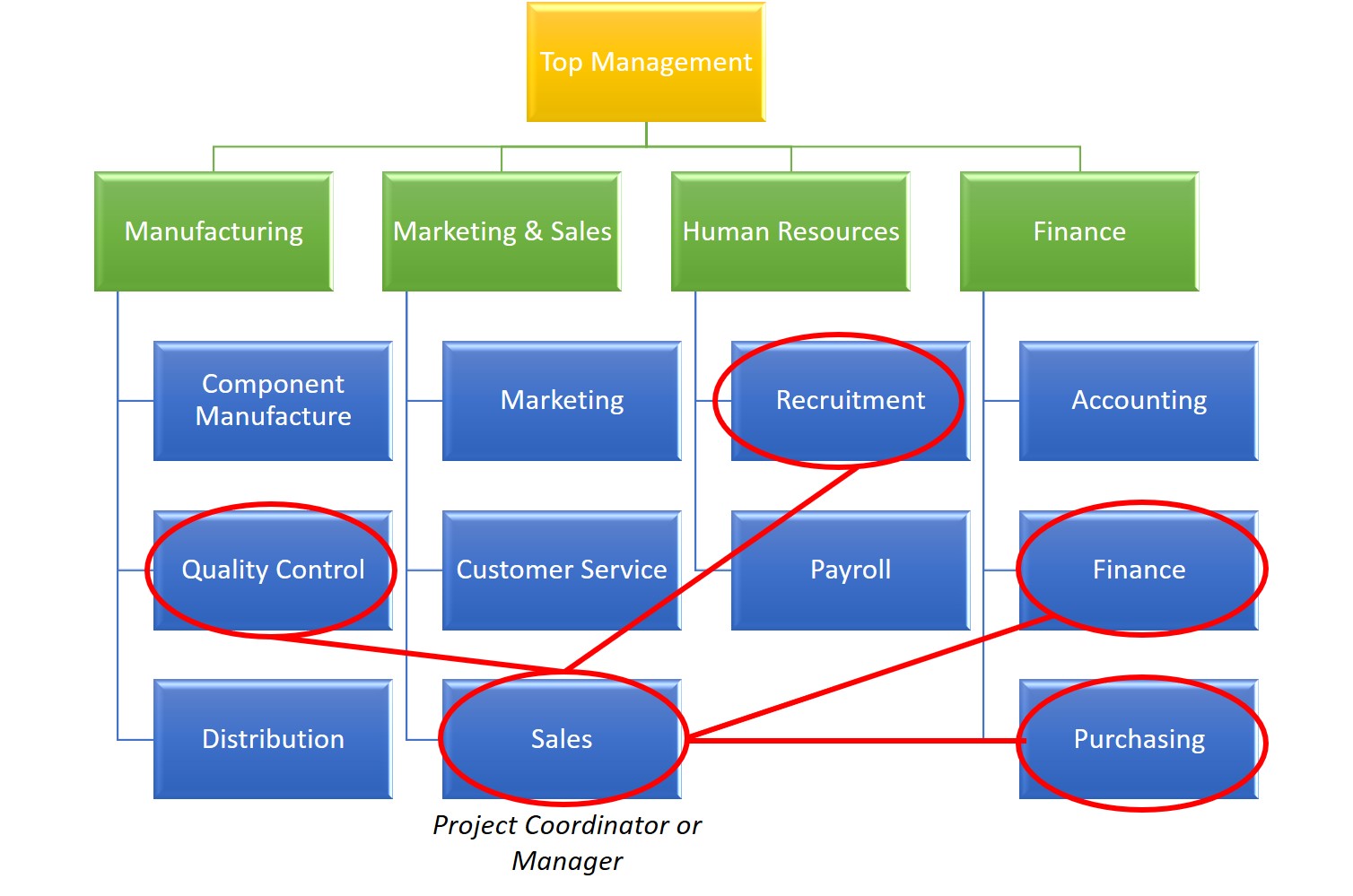

Moving to the right on the spectrum (Figure 3.3.2), we can arrive at a weak matrix organization where functional units still exist. Still, the role of the project manager also becomes more well-defined and might even be its own role within the organization. In a weak matrix, the project manager still works part-time in their department while having more authority than in a functional organization, but at a low level (Figure 3.3.4).

As we continue across the spectrum, we now have a balanced matrix organization type in which we may have a designated project manager with a higher authority. The project manager may manage the project budget to some extent, but not completely, although the functional manager still has more say.

As illustrated in Figure 3.3.5, a Project Management Office (PMO) or a designated program management office is added in a strong matrix organization type besides functional departments. This department employs full-time project managers with a designated job role. They manage the project budget, and their authority becomes moderate to high. They can also have a full-time administrative staff. This organizational structure may be preferred by many project managers since they can acquire qualified and experienced team members from functional departments inside the organization while they have higher levels of authority.

3.3.1.3 Project-Oriented (Projectized) Organizational Structure

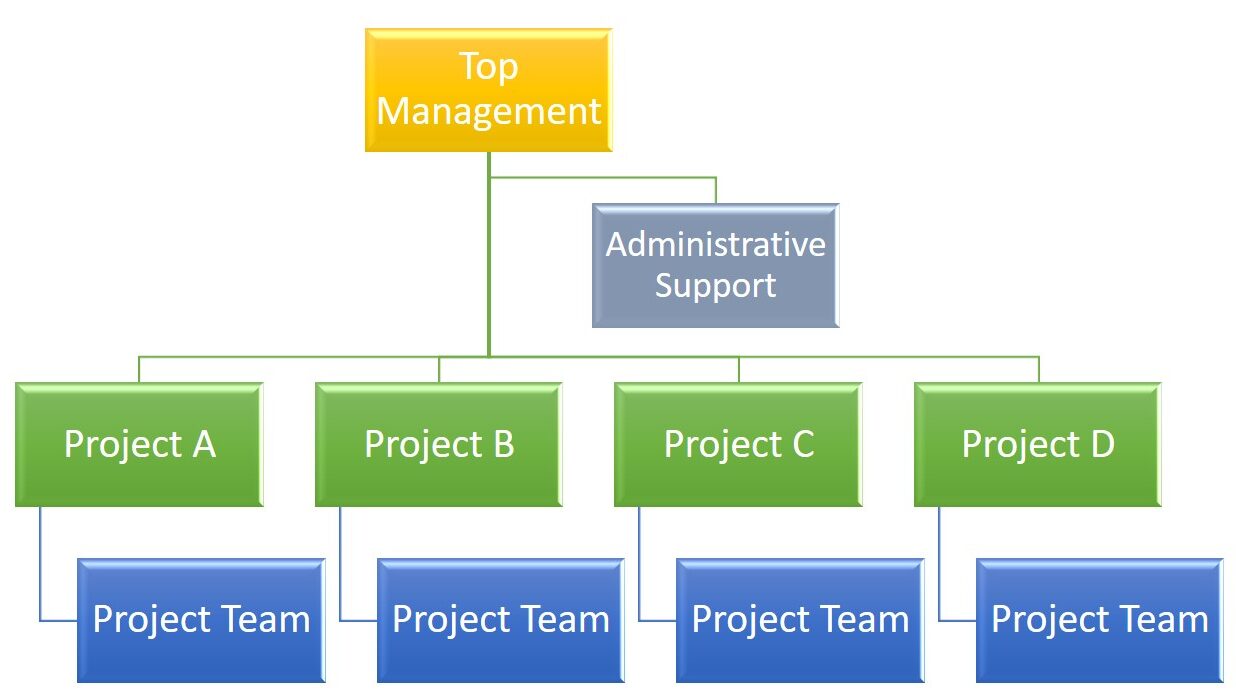

In a project-oriented or projectized organization, tasks are arranged by projects, not functions (Figure 3.3.6). Project managers work independently with a high authority, having full-time designated job roles. However, they may have some challenges while acquiring human resources and other resources since the organization doesn’t have specialized departments where skilled and experienced employees work.

3.3.2 Informal Subsystem

When working with internal stakeholders (those inside an organization) and external stakeholders (those outside an organization) on a project, it is essential to pay close attention to the hierarchy and authority relationships, relationships, context, history, and corporate or organizational culture. Organizational (corporate) culture refers to the beliefs, attitudes, and values that the organization’s members share and the behaviors consistent with them (which they give rise to). Organizational culture sets one organization apart from another and dictates how members of the organization will see you, interact with you, and sometimes judge you. Often, projects also have a specific culture, work norms, and social conventions (see Chapter 6).

An organization’s culture is defined by the shared values and meanings its members hold in common, articulated and practiced by its leaders. Purpose, embodied in corporate culture, is embedded in and helps define organizations. Ed Schein, one of the most influential experts on culture, also defined organizational corporate culture as “a pattern of shared tacit assumptions learned or developed by a group as it solves its problems of external adaptation and internal integration that have worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.[1]” Some aspects of organizational culture are easily observed; others are more difficult to discern. We can easily observe the office environment and how people dress and speak. In one company, individuals work separately in closed offices; in another, teams may work in a shared environment. The subtler components of organizational culture, such as the values and overarching business philosophy, may not be readily apparent, but they are reflected in member behaviors, symbols, and conventions used. Organizational culture can give coworkers a sense of identity through which they feel they are an indispensable component of a larger and stronger structure.

Some cultures are more conducive to project success than others. As a project leader, it is very important to understand the unique nature of the corporate culture that we operate in. This understanding allows us to put in place the processes and systems most likely to lead to project success.

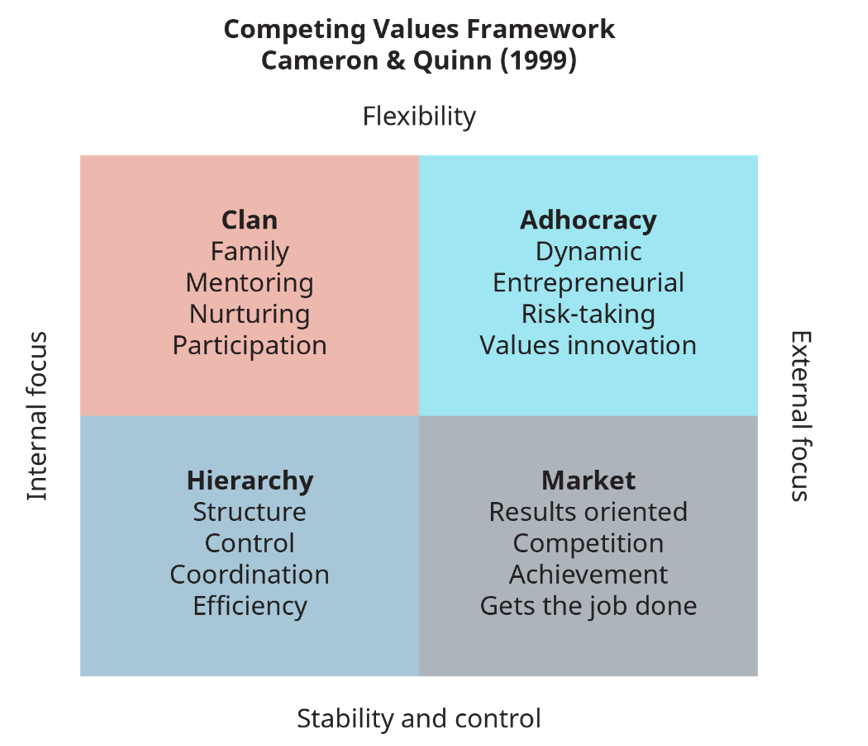

Organizational culture is considered one of the most important internal dimensions of an organization’s effectiveness criteria. An influential management guru, Peter Drucker, once stated, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.”[2] He meant that corporate culture is more influential than strategy in terms of motivating employees’ beliefs, behaviors, relationships, and ways they work since culture is based on values. Strategy and other internal dimensions of an organization are also very important. Still, organizational culture serves two crucial purposes: First, culture helps an organization adapt to and integrate with its external environment by adopting the right values to respond to external threats and opportunities. Secondly, culture creates internal unity by bringing members together to work more cohesively to achieve common goals. Culture is both the personality and glue that binds an organization. It is also important to note that organizational cultures are generally framed and influenced by the top-level leader or founder. This individual’s vision, values, and mission set the “tone at the top,” influencing ethics and legal foundations and modeling how other officers and employees work and behave. The Competing Values Framework offers a framework used to study how an organization and its culture fit the environment (Figure 3.3.7).

(Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC-BY 4.0 license)

Assume you are leading a project in an organization with a hierarchical culture. Projects are about changing the way an organization operates. Introducing change in an organization with this type of culture can be challenging because they value caution, conservative approaches, and careful decision-making. Suppose the project you are leading involves introducing innovative practices and technologies. In that case, getting the approvals required to proceed at its various stages may be very difficult and time-consuming. Innovative practices are not guaranteed to work; success requires high risk tolerance in decision-making processes. This may be difficult to achieve in organizations with this type of culture.

Furthermore, the already aggressive schedule of employees in hierarchal organizations may not be able to accommodate the potential numerous and lengthy deliverable reviews required for innovative projects, causing project success to be viewed as unachievable. Project leaders in this type of culture are wise to speak openly and candidly about the project’s risks and plan for additional deliverable reviews as a way of setting the project up for success. If this very same innovative project was being delivered in an organization with a market culture, the decision-making approach and the schedule are likely to be fundamentally different.

- Schein, E. (2017). Organizational culture and leadership, 5th ed., Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. ↵

- Hyken, S. (2015, December 5). Drucker said the culture eats strategy for breakfast. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/shephyken/2015/12/05/drucker-said-culture-eats-strategy-for-breakfast-andenterprise-rent-a-car-proves-it/#7a7572822749 ↵