Chapter 6. Communication Management, Leadership, and Project Team Management

6.4 Leadership Skills

Project managers, as leaders, spend 90% of their time communicating with team members and stakeholders[1]. They communicate through various channels, including in-person meetings, emails, video conferences, phone calls, instant messaging, and collaborative platforms like Microsoft Teams or Slack. Project managers must also adapt their communication style to suit different audiences, ensuring clarity when discussing project updates with team members, stakeholders, clients, or executives. Their communication involves reporting progress, addressing risks, resolving conflicts, motivating the team, and managing expectations. Additionally, they must facilitate regular status meetings, issue tracking updates, and feedback sessions, ensuring that everyone involved in the project remains aligned on goals, tasks, and deadlines.

Communication is the most important leadership skill a project manager should possess, but not the only one. Project managers need many skills, including administrative skills, organizational skills, and technical skills associated with the project’s technology. The types of skills and the depth of the skills needed are closely connected to the size and complexity of the project. Each project must be tailored to various factors, including the purpose, objectives, business field, size, complexity, and stakeholders. Although project managers always need interpersonal skills to communicate and collaborate effectively with the team members and stakeholders, they need greater technical skills on smaller, less complex projects. Project managers need more organizational skills to deal with the complexity of larger and more complex projects.

Leadership skills involve guiding, motivating, and directing a team. Leadership is defined as a social (interpersonal) influence relationship between two or more persons who depend on each other to attain certain mutual goals in a group situation. Effective leadership helps individuals and groups achieve their goals by focusing on the group’s maintenance needs (the need for individuals to fit and work together by having, for example, shared norms) and task needs (the need for the group to make progress toward attaining the goal that brought them together)[2]. These skills include negotiation, resilience, communication, problem-solving, critical thinking, and interpersonal skills.

A large part of the project manager’s role involves dealing with people. Hence, project managers should study people’s behaviors and motivations. Project managers must be perceived to be credible by the project team and stakeholders. They should detect and clarify the ambiguities effectively to remove the obstacles. The environment changes frequently on projects, and the project manager must apply the appropriate leadership approach for each situation. They must have good communication skills. Lack of communication, team-building, and organizational skills would cause problems in a project and could lead to failure.

Let’s use the analogy of a music conductor, which is a perfect example to convey the responsibilities and skills of a project manager. An orchestra conductor coordinates a variety of performers who play different instruments and should ensure that the audience enjoys the music on the day of the performance. It may be a chamber orchestra composed of 25 musicians or a large one like a symphony orchestra with up to 100 members. The conductor cannot know how to play all the instruments in an orchestra, but only one or a few. However, the conductor must ensure that all the performers playing the instruments, including but not limited to violins, violas, cellos, double basses, flutes, oboes, clarinets, kettledrums, and harps must create a piece of music in harmony so that the audience can enjoy. Conductors perform many rehearsals with all the performers to achieve this harmony. During these rehearsals and the performance, most of the conductor’s work would be regarding communication with all the performers.

The project manager leads the project team during a project life cycle. As explained in Chapter 2, project managers may start working in the pre-project phase (preparation of a need statement, business case, and benefits realization management plan) to assess the feasibility of candidate projects, especially when the organization has a dedicated PMO (Project Management Office) or has a strong matrix or project-oriented structure. However, in general, project managers are assigned to the initiation (starting, conceptualization) phase or the planning phase after the project charter is approved by the project sponsor. A project manager may be involved after the project is closed out to evaluate the performance of the outcome and, more importantly, to evaluate if the outcome can generate the expected value (both tangible and intangible values as detailed in measurable project objectives). Although we use the term “project manager” in this textbook, you can come across various concepts such as project leader, project lead, and project coordinator in other resources and also in this textbook in different sections. We assume in this textbook that a project manager is also a project leader and should possess interpersonal leadership skills.

In the following subsections, we will focus on leadership and interpersonal skills a project manager should possess.

6.4.1 Listening

One of the most important communication skills of the project manager is the ability to listen actively. Active listening is placing oneself in the speaker’s position as much as possible, understanding the communication from the speaker’s point of view, observing and paying attention to the body language and other environmental cues, and striving not just to hear but to understand. Active listening takes focus and practice to become effective. It enables a project manager to go beyond the basic information being shared and develop a more complete understanding.

Example: Client’s Body Language[3]

We work with a client on a project. The person in charge of the project at the client company just returned from a trip to Australia, where he reviewed the project’s progress with his company’s board of directors. Then, he visited our office for a meeting with our project team. The project manager listened and took notes on the five concerns the board of directors expressed to him during his visit to Australia.

Our project manager observed that the client’s body language showed more tension than usual. This was a cue to listen very carefully. The project manager nodded occasionally and demonstrated he was listening through his posture, small agreeable sounds, and body language. The project manager then began to provide feedback on what was said using phrases like “What I hear you say is…” or “It sounds like.…” The project manager was clarifying the message that was communicated by the client.

The project manager then asked more probing questions and reflected on what was said. “It sounds as if it was a very tough board meeting.” “Is there something going on beyond the events of the project?” From these observations and questions, the project manager discovered that the board of directors meeting in Australia did not go well. The company had experienced losses on other projects, and budget cuts meant fewer resources and an expectation that the project would finish earlier than planned. The project manager also discovered that the client’s future with the company would depend on the project’s success. The project manager asked, “Do you think we need to do things differently?” They began to develop a plan to address the board of directors’ concerns.

Through active listening, the project manager was able to develop an understanding of the issues that emerged from the board meeting and participate in developing solutions. Active listening and the trusting environment established by the project manager enabled the client to share information he had not planned on sharing safely and to participate in creating a workable plan that resulted in a successful project.

In the example above, the project manager used the following techniques:

- Listening intently to the words of the client and observing the client’s body language

- Nodding and expressing interest in the client without forming rebuttals

- Providing feedback and asking for clarity while repeating a summary of the information back to the client

- Expressing understanding and empathy for the client

Therefore, as seen in the example, active listening was important in establishing a common understanding from which an effective project plan could be developed.

6.4.2 Negotiation

When multiple people are involved in an endeavor, differences in opinions and desired outcomes naturally occur. Negotiation is a process for developing a mutually acceptable outcome when the desired outcome for each party conflicts. A project manager often negotiates different aspects of a project (e.g., scope, schedule, budget, quality, purchases, conflicts with stakeholders) with the client, team members, vendors, and other project stakeholders. Negotiation is an important skill in developing support for the project and preventing frustration among all parties involved, which could delay or cause project failure. Negotiation is used to achieve support or agreement that supports the project’s work or its outcomes and to resolve conflicts within the team or with other stakeholders.

Negotiations involve four principles:

- Separate people from the problem:

- Framing the discussions in terms of desired outcomes enables the negotiations to focus on finding new outcomes.

- Focus on common interests:

- By avoiding the focus on differences, both parties are more open to finding acceptable solutions.

- Generate options that advance shared interests:

- Once the common interests are understood, solutions that do not match either party’s interests can be discarded, and solutions that may serve both parties’ interests can be more deeply explored.

- Develop results based on standard criteria:

- The standard criterion is the project’s success. This implies that the parties develop a common definition of project success.

For the project managers to successfully negotiate issues on the project, they should first seek to understand the other party’s position. They should figure out the concerns and expectations of team members or stakeholders with whom they will negotiate, as well as the business drivers and personal drivers that are important to them. Without this understanding, finding a solution that will satisfy them is difficult. Project managers should also seek to understand the desired outcomes for the project. Typically, more than one outcome is acceptable. Without knowing what outcomes are acceptable, finding a solution that will produce that outcome is difficult.

6.4.3 Conflict Management

Conflict on a project can be expected for various reasons, such as the level of stress, lack of information during the early phases of the project, personal differences, role conflicts, and limited resources. Although good planning, effective communication, and healthy team building can reduce conflict, conflict will still emerge. Therefore, project managers must be prepared to deal with the conflicts effectively.

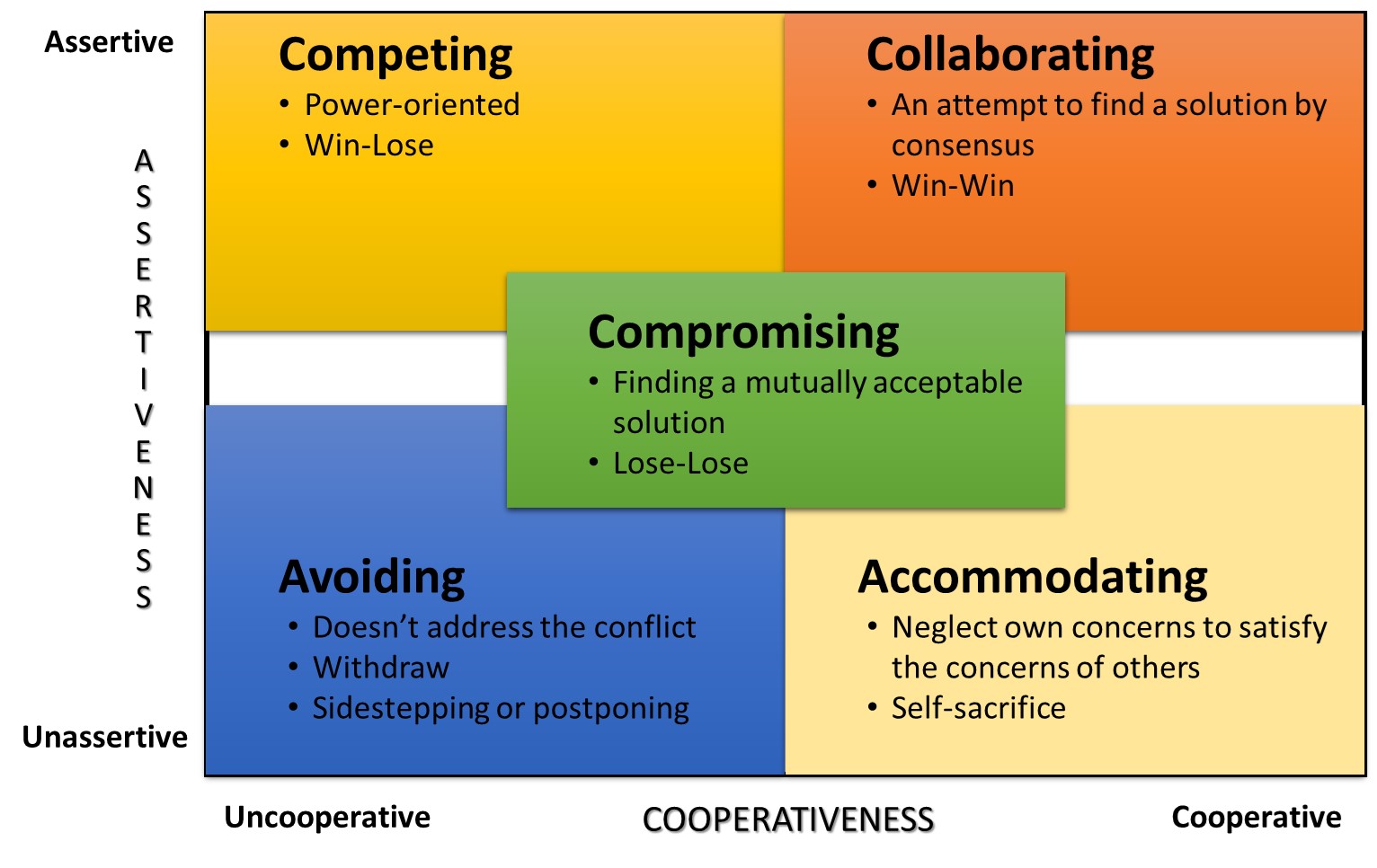

One of the well-known conflict management models is the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI), which assesses an individual’s behavior in conflict situations when the concerns of two people appear to be incompatible[4]. This model is based on two dimensions describing a person’s conflict behavior.

- Assertiveness: The extent to which the individual attempts to satisfy his or her own concerns.

- Cooperativeness: The extent to which the individual attempts to satisfy the other person’s concerns.

According to the different levels of these two dimensions, the model defines five methods to deal with conflicts (Figure 6.1).

Competing (forcing) is assertive and uncooperative. It is a power-oriented mode in which an individual pursues their own concerns at the other person’s expense, using whatever power seems appropriate to win their position.

Collaborating is both assertive and cooperative. An individual attempts to work with the other person to find a solution that fully satisfies both concerns. It involves digging into an issue to identify the underlying concerns of the two individuals and finding an alternative that meets both sets of concerns.

Compromising is intermediate in both assertiveness and cooperativeness. The objective is to find an expedient, mutually acceptable solution that partially satisfies both parties. Compromising might mean splitting the difference, exchanging concessions, or seeking a quick middle-ground position.

Avoiding is unassertive and uncooperative. When avoiding, an individual does not immediately pursue their own concerns or those of the other person. They do not address the conflict. Avoiding might be diplomatically sidestepping an issue, postponing an issue until a better time, or simply withdrawing from a threatening situation.

Accommodating is unassertive and cooperative, which is the opposite of competing. In this mode, an individual neglects his or her own concerns to satisfy the other person’s concerns. Therefore, there is an element of self-sacrifice.

Each of these approaches can be effective and useful depending on the situation. Project managers will use each conflict resolution approach depending on the project manager’s personal approach and an assessment of the situation. Most project managers have a default approach that has emerged over time and is comfortable. For example, some project managers find using the project manager’s power the easiest and quickest way to resolve problems. “Do it because I said so” is the mantra for project managers who use competing as the default approach to resolving conflict. The competing approach often succeeds when a quick resolution is needed, and the investment in the decision by the parties involved is low. Some project managers find accommodating the client the most effective approach to resolving conflict.

Two examples have been provided below to elaborate on project conflict resolution methods.

Resolving an Office Space Conflict[5]

Two senior managers both want the office with the window. The project manager intercedes with little discussion and assigns the window office to the manager with the most seniority. The situation was a low-level conflict with no long-range consequences for the project and a solution all parties could accept. Therefore, the project manager applied the competing (forcing) method. Sometimes office size and location are culturally important, requiring more investment to resolve.

Conflict Over a Change Order[6]

The client rejected a request for a change order because she thought the change should have been foreseen by the project team and incorporated into the original scope of work. The project controls manager believed the client was using her power to avoid an expensive change order and suggested the project team refuse to do the work without a change order from the client. This is a more complex situation, with personal commitments to each side of the conflict and consequences for the project. The project manager needs a conflict resolution approach that increases the likelihood of a mutually acceptable solution for the project.

One conflict resolution approach involves evaluating the situation, developing a common understanding of the problem, developing alternative solutions, and mutually selecting a solution. Evaluating the situation typically includes gathering data. In this example, gathering data would include a review of the original scope of work and possibly of people’s understandings, which might go beyond the written scope.

The second step in developing a resolution to the conflict is to restate, paraphrase, and reframe the problem behind the conflict to develop a common understanding of the problem. In our example, the common understanding may explore the change management process and determine that the current change management process may not achieve the client’s goal of minimizing project changes. This phase is often the most difficult and may take an investment of time and energy to develop a common understanding of the problem.

Alternative approaches are developed after the problem has been restated and agreed on. This creative process often means developing a new approach or changing the project plan. The result is a resolution to the conflict that is mutually agreeable to all team members. If all team members believe every effort was made to find a solution that achieved the project charter and met as many of the team member’s goals as possible, there will be a greater commitment to the agreed-on solution.

6.4.4 Trust

Building trust in a project begins with the project manager. Assigning a project manager with a high trust reputation on complex projects can help establish the trust level needed. The project manager can also establish the cost of lying in a way that communicates an expectation and a value for trust in the project. Project managers can also ensure that the official goals (stated goals) and operational goals (goals that are reinforced) are aligned. The project manager can create an atmosphere where informal communication is expected and reinforced.

Informal communication is important for establishing personal trust among team members and with the client and other stakeholders. Allotting time during project start-up meetings to allow team members to develop personal relationships is important to establishing team trust. The informal discussion allows for a deeper understanding of the whole person and creates an atmosphere where trust can emerge.

Small events that reduce trust often occur on a project without anyone remembering what happened to create an environment of distrust. Taking fast and decisive action to establish a high cost of lying, communicating the expectation of honesty, and creating an atmosphere of trust are critical steps a project manager can take to ensure the success of complex projects.

Project managers can also establish expectations of team members to respect individual differences and skills, look and react to the positives, recognize each other’s accomplishments, and value people’s self-esteem to increase a sense of benevolent intent.

6.4.5 Emotional Intelligence (EQ)

Emotions are neither positive nor negative. Emotions are both a mental and physiological response to environmental and internal stimuli. Project managers must understand and value their emotions to appropriately respond to the client, project team, stakeholders, and project environment. Daniel Goleman (Goleman, 1995) discussed emotional intelligence quotient (EQ) as a factor more important than IQ in predicting leadership success[7]. Emotional intelligence is the ability to sense, understand, and effectively apply the power and acumens of emotions as a source of human energy, information, connection, and influence (Cooper and Sawaf, 1997)[8].

Emotional intelligence includes the following:

- Self-awareness

- Self-regulation

- Empathy

- Relationship management

Emotions are important to generating energy around a concept, building commitment to goals, and developing high-performing teams. Emotional intelligence is an important part of the project manager’s ability to build trust among the team members and with the client. It is important to establish credibility and open dialogue with project stakeholders. Emotional intelligence is a critical ability for project managers, and the more complex the project profile, the more important the project manager’s EQ becomes to project success.

- Project Management Institute. (2017). A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK guide) (6th ed.). Project Management Institute. ↵

- Retrieved from the OER titled “Principles of Management” on https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/13-1-the-nature-of-leadership ↵

- Retrieved from the OER titled “Project Management” by Adrienne Watt on https://opentextbc.ca/projectmanagement/chapter/chapter-11-resource-planning-project-management/ ↵

- Thomas, K. W. (2008). Thomas-Kilman conflict mode. TKI Profile and Interpretive Report, 1-11. ↵

- Retrieved from the OER titled “Project Management” by Adrienne Watt on https://opentextbc.ca/projectmanagement/chapter/chapter-11-resource-planning-project-management/ ↵

- Retrieved from the OER titled “Project Management” by Adrienne Watt on https://opentextbc.ca/projectmanagement/chapter/chapter-11-resource-planning-project-management/ ↵

- Goleman, D. (1996). Emotional intelligence. Why it can matter more than IQ. Learning, 24(6), 49-50. ↵

- Cooper, R. K., & Sawaf, A. C. (1997). Executive EQ: Emotional intelligence in leadership and organization (No. 658.409 C7841c Ej. 1 000003). ↵