Inclusive Teaching

What does it mean to be Inclusive in Higher Education

Thijs Heus

At first glance, it may seem like a simple question: the goal is to ensure that individuals from all backgrounds – regardless of their race/ethnicity, disability status, socioeconomic status, or whether they are first-generation students or not – have the opportunity to achieve their full potential. However, achieving this goal is not always easy, and it requires a multifaceted approach.

Scholars like Tracy Addy advocate for anti-discrimination techniques in the classroom, including values affirmation exercises (Mikiyake, 2010), vigilance against micro-aggressions, and Universal Design practices (Tobin and Behling, 2018). Meanwhile, Hogan and Sathy take a more pragmatic approach, emphasizing the importance of designing high-structure courses that prioritize active learning. Both approaches are valuable and can contribute to creating a more inclusive learning environment.

It is essential to recognize that promoting inclusivity in Higher Education requires systemic changes, including improvements in general teaching methods. In many cases, instructors are not primarily trained in pedagogy, and it may not be the primary criterion for hiring or promotion. However, inclusive teaching benefits all students, particularly those who are most vulnerable. For instance, a focus on decreasing DFW rates (i.e., rates of students who receive a grade of D, F, or Withdrawal) through better teaching can help bridge the success gap between different student groups.

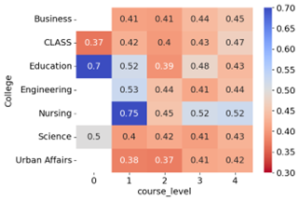

While a focus on the DFW gap is important, it often leads to a narrow focus on “gateway classes” as a quick fix. These are large classes typically at the 100/200 level, which are often prerequisites for upper-level courses, and they tend to have a high DFW rate, particularly in STEM courses. However, it is important to note that outside of gateway classes, minoritized students do not suddenly achieve parity. In an equitable world, the median Black student would receive the same grade as the median White student. Unfortunately, Figure 1 shows that the median Black student’s grade hovers around the 42nd percentile overall, regardless of domain or course level. This is particularly concerning since arguments about under preparedness become less valid at the 300 level. When almost every class, at every level, and every college shows such a gap, it is clear that a narrow focus on a select few courses will not be enough to address the issue.

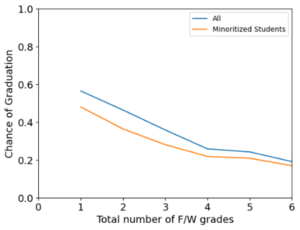

Graduating from college is a significant milestone, and Black students face numerous barriers to reaching that goal – not just in the classroom. A single F or W in any course lowers the chances of graduation to 60%, and for Black students, this number falls to less than 50%. If a student receives four Fs, the chance of dropping out of college is 40%, and with three Fs, it increases to 80% (Figure 2).

In popular cartoons, inequities are often depicted as a race track, flat for the majority participant, but covered with hurdles for the minoritized participant. Perhaps the more accurate depiction would be a minefield instead of merely a few hurdles: Any single event could be an immediate termination of a career that was supposed to be jumpstarted in college. But while removing a few mines out of the minefield statistically helps DFW rates, equity is only achieved when all mines are removed, and the participants know that to be true. After all, even the chance of a single mine would make most people opt-out from participating, and even if they would, move with a lot of caution and stress.

To bring back the minefield analogy to the university, we are unlikely to see much results in terms of participation, retention, and graduation, until we tackle all problems. That doesn’t mean that the case is hopeless, or that we should give up on classroom opportunities, on the contrary: It means that we should do better and more inclusive teaching in the classroom. It means that we should explore study-halls or other solutions to address inequities in homework situations . It means exploring our degree maps and graduation requirements against rigidities, such as courses that can immediately delay graduation if failed. It means exploring more Last Mile scholarships, and better opportunities for taking courses in the summer. It means admitting that for students with family or financial obligations, a 15-credit hour semester is a set up for failure, and degree maps and scholarship structures need to be adjusted as such. It means having more on-campus work opportunities and allowing students to occasionally work more than 20 hours, as long as their semester is going well. It means re-exploring on-campus childcare. It means ensuring that advising has the tools they need, so that they can give long-term advice as well as get-through-the-semester advice. It means ensuring that the hidden curriculum and campus procedures are so clear and multi-modally accessible that an advisor is not even necessary to navigate them, and that mistakes can be fixed quickly and without harm to the student.

It means, for starters, to ask the students. We only have a Student Evaluation of Instruction (SEI), but no evaluation of the Semester. Adding a few overall questions on class schedule, overall performance, and campus environment could help our overall efforts. Our Student Evaluation of Instruction is currently set up as a summative assessment of the instructors, with topics like how knowledgeable the instructor is. Just like a deficit mind set is not working for the students, it does not work for instructors either. It would help to have the SEI focus on constructive feedback on topics that students have a better.

[1] According to many guidelines, students should spend the majority of study time (at least 2 hours per credit hour) outside the classroom. I could find little literature on how to create an equitable homework situation, but a welcoming, well-equipped, structured, on-campus environment that fosters collaboration might help.

[1] As is the peer evaluation.