Chapter 4: The Impact of Religion and Hierarchy on African Art

Chapter 4.1 Traditional Religion and Art

Much of traditional African art is secular. It may relate to personal adornment for reasons of status, age, or ethnic identity, or consist of pottery used for domestic water use. It could be associated with a secret society’s instruction or served as a sculpted door for a home. It might be sculpture or architecture that reinforces the prestige of a ruler or his courtiers, or a masquerade whose sole purpose is community entertainment (Fig. 533), perhaps with a satirical component meant to

reinforce moral values. It can manifest as a domestic or work utensil (Fig. 534) part of a game, a musical instrument, or even a gambling chip (Fig. 535). Sometimes lack of information and context makes it impossible to identify its original function (Fig. 536). While such secular items are numerous, traditional sacred art, however, probably constitutes the better-known direction of African art.

Traditional religion itself manifests nearly as many forms as there are ethnicities. Most peoples believed in a High God, but felt he or she was too distant from humanity to take much interest in peoples’ affairs. Instead, they focused on ancestors and/or spirits or deities as beings to plead with, asking for favor or apologizing for shortcomings. While these efforts did not always involve art forms, they frequently did. Artistic objects might be personal, family-owned, or community-based. In the past century, however, traditional religion has felt the increasing squeeze of Christianity and Islam. While both of these religions have had an African presence for centuries, they are increasingly attracting followers who ignored, actively avoided pressure, or were unaware of them before. In some areas, individuals are

comfortable straddling the worlds of their traditional religion and that of an adopted religion, adhering to one or the other as the occasion demands. Some, however, completely reject traditional religion. This has led to a depletion of associated art forms, or, in some cases, their complete abandonment.

The Edo of Nigeria’s Benin Kingdom, for example, believe in a High God known as Osanobua; Christian churches there use this name to also refer to the Christian High God. Although frequently called upon in daily speech–in the order of “Oh, my God!”–few shrines or priests were or are dedicated to him. Instead, his three children were once the subjects of extensive worship. The eldest, a female named Obienmwen, was associated with farming (particularly of yams) and childbirth. The youngest, Ogiuwu, was the Lord of Death, and once had a major shrine near the palace entrance, the site of sacrifice. Both of these deities have essentially fallen by the wayside. A few Obienmwen priestesses persist, but without large-scale community temples or support. The

British suppressed the worship of Ogiuwu at the time of their 1897 invasion, and he is referred to historically rather than visibly honored. The middle child of the High God, however, retains some of his former glory. Olokun, lord of the sea, is the deity of the sea and wealth, as well as the supplier of children. He lives in an underwater palace filled with coral beads, brassware, and other riches.

Formerly almost every Edo female had a small altar to Olokun to ensure her fertility (Fig. 537), and went through at least the first stage of initiation if there were any concerns about her well-being. These are covered with layers of kaolin chalk, which is found by riversides and is the Edo symbol of joy, peace, and purity. Great men also have Olokun altars to ensure their wealth. Their core is a clay construction embedded with cowrie shells, the region’s pre-colonial currency. This may be placed in the midst of an ensemble of large unfired clay figures that depict Olokun, his wives, and his court (Fig. 538). Their poses and dress are like those found at the Benin ruler’s palace, for the latter is said to be a reflection of Olokun’s realm. These sculptural tableaux are also the focus of state Olokun shrines and those belonging to priestesses; they are normally made by women. Despite the continuance of this tradition, it is shrinking as Christianity continues to grow. The semi-accommodation granted by Catholicism, the Anglican/Church of Nigeria, and other Christian denominations has been rejected by those belonging to the rapidly-adopted Pentecostal/evangelical sects, and Olokun participation by young girls has dropped off considerably.

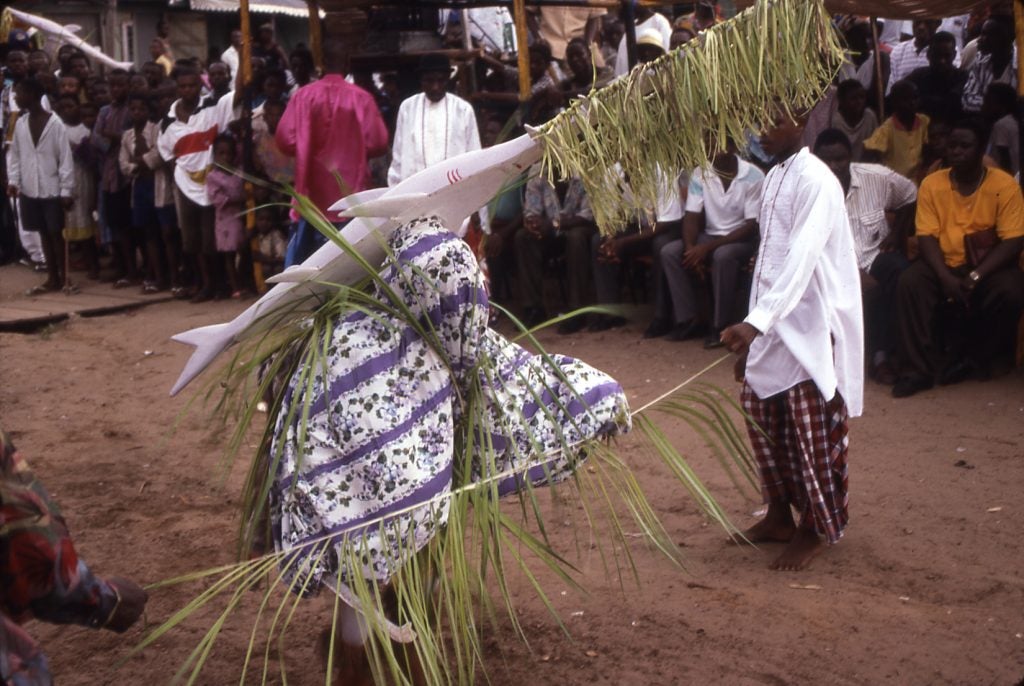

When traditional religion is wrapped up with cultural identity, it tends to persist, at least in part. Although Christianity is a large part of the life of many of the Ijo/Izon of coastal Nigeria, masquerades that honor the water spirits have not vanished. Ijo life in the Niger Delta, riddled with rivers and creeks, has long been wrapped up with fishing, trade, and now offshore oil reserves–all enriched and made possible by water. Their masquerades enter the village from the shores, and perform in the guises of highly abstract composite creatures (Fig. 539) or more identifiable ones. Even when they take human form, they represent spirits from the watery realm (ekine) who interact periodically with their admirers and grant favors when satisfied with them. Each has its own music and dance, as well as a priest who sacrifices to them from a waterside shrine. The Delta neighbors of the Ijo have adopted and adapted these water deities over time; Itsekiri, Igbo, Urhobo and riverine Yoruba masquerades reflect their impact. In some non-Ijo areas where Christianity is particularly prevalent, the masquerades have dropped their spiritual aspects and have been adopted by social clubs who perform with them at either Christmas, New Year’s, or Easter; they have no priests nor shrines and are considered forms of cultural expression (Fig. 540).

Further Reading

Anderson, Martha G. and Philip M. Peek, eds. Ways of the rivers: arts and environment of the Niger Delta. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 2002.

Ben-Amos, Paula. “Artistic creativity in Benin Kingdom.” African Arts 19 (3, 1986): 60-63; 83-84.

Fagg, Bernard. Nok Terracottas. Lagos: Ethnographica for the National Museum, 1977.

Fischer, Eberhard. Guro. Munich: Prestel, 2008.

Galembo, Phyllis, ed. Divine inspiration: from Benin to Bahia. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1993.

Quinn, Frederick. “Abbia Stones.” African Arts 4 (4, 1971): 30-32.

The Bwa of Burkina Faso and Southeastern Mali

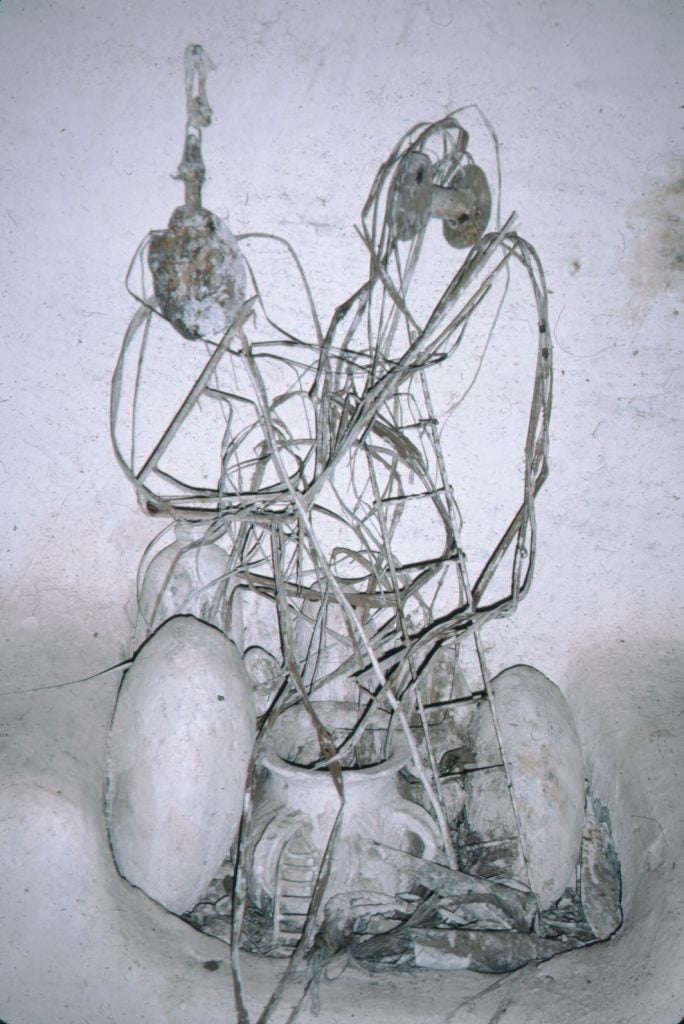

Ancestors, deities, and spirits make up critical aspects of many traditional African religions, although art may relate only to certain of these aspects–or none at all. The majority of the Bwa people of Burkina Faso still practice traditional religion. They believe in a High God known as Difini or Dobweni, who created the world and mankind, then withdrew from contact. He left behind his son, Do, embodied by a masquerade that represents the life force and is meant to mediate between men and the bush, the uncultivated wilderness that provides meat via animals, as well as some other foodstuffs and plants and other materials used for supernatural medicines. He is the Nature god, and also the power behind successful farming. The Bwa actually adopted the Do masquerade (bieni) centuries ago from their neighbors the Bobo, an ethnic group that is part of the Mande world. Its construction is from bush materials–leaves, vines, wild stalks, grasses, porcupine quills, and white feathers from hornbills and hawks–and it is not meant to have a human-like appearance (Fig. 541). The performer is wrapped in vines before the costume is created around him; he becomes nearly invisible inside a constructed forest enclosure, although his hands and feet can be seen. The dance of the bieni–several perform at the same time–involves rapid quivering that impresses viewers with godly creativity. Both male and female initiates interact with the dancers, the elders praising them by raising their arms during their frequent appearances at initiations and community purification ceremonies, as well as their

performance at Do worshippers’ funerals. These leaf masks occur among all Bwa sub-groups and are ephemeral, destroyed after the day’s performance (except for the feathers) only to be reconstructed in future, just as the growth cycle incorporates sprouting, full growth, death, and resprouting.

The Bwa of Burkina Faso, however, also have a second type of masquerade that includes carved wooden masks. These are a fairly recent adoption from several of their eastern neighbors, including the Nunuma, Winiama, and Nuna, just about 120 years ago. They never perform at the same occasions as Do worshippers and are often in conflict with

them. These wooden masks represent protective nature spirits, not gods, and are family-owned, performing at initiations, burials, funerals, and public civic and market occasions. A family’s masks relate to their stories of particular supernatural beings that intervened on behalf of specific ancestors, helping them escape danger or leading them to prosperity. The masks honor these spirits and commemorate the encounters.

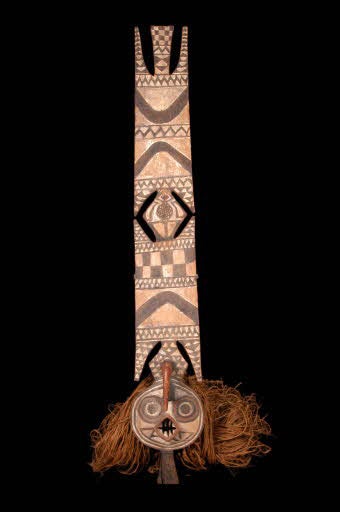

Bwa monoxyl masks often soar high in the air, the plank-like forms recalling some Dogon masks as well as certain other nearby peoples who, like the Bwa, belong to the larger category of Gur-speaking peoples. Nature spirits are supernatural beings, but they often choose forms that are familiar–animals like the snake (Fig. 542), the antelope, the buffalo, the crocodile, butterflies (Fig. 543), the rarer bat and fish, or abstract masks that represent “human” or supernatural characters (Fig. 544). Performers’ costumes are made from wild raffia fibers, but are now frequently dyed. Their dances and musical accompaniment vary according to their nature, but require considerable athleticism and endurance.

The masks usually have graphic elements–concentric circles, triangles, checkerboards, and zig-zag lines–carved in relief on their surfaces, which are conventionally painted in red, black, and white. Red, a color of danger and power, is associated with the spirits. The symbols carry meaning to initiates; zig-zag lines represent the difficult but desirable path of following the ancestors, while the checkerboard indicates that greater knowledge comes with age–white squares represent the ignorance of the newly-initiated, black squares the wisdom of elders. Chevrons allude to a sacred serpent, and the “X” form represents an archaic kind of scarification once worn on the foreheads of both male and female initiates, who go through initiation (and its accompanying circumcision and excision) together. These masks continue to evolve; carved inscriptions and figurative images now appear on some examples.

Whether fiber or wooden masks, performance shows a close relationship between initiated citizens of both sexes and the spirit world.

Further Reading

Coquet, Michèle. “Faceless gods: on the morphology of Bwaba leaf masks.” In Luc de Heusch, ed. Objects: Signs of Africa, pp. 21-35. Ghent, Belgium: Snoeck-Ducaju & Zoon, 1995.

Roy, Christopher D. “The laws of man and the laws of God: graphic patterns in Voltaic art.” Baessler Archiv, n.s. 47 (1, 1999): 223-258.

Roy, Christopher D. “Leaf masks among the Bobo and the Bwa.” In Frank Herreman, ed. Material differences: art and identity in Africa, pp. 122-127. New York: Museum for African Art/Ghent, Belgium: Snoeck-Ducaju & Zoon, 2003.

Roy, Christopher D. “Nature, Spirits and Arts in Burkina Faso.” Art and Life in Africa website, University of Iowa.

The Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria and Benin Republic

One of the most complex traditional religions is that of the Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria and its western neighbor, Benin Republic. The Yoruba believe in a High God known as Oludumare, who, like the High God in many African religions, is somewhat withdrawn from humanity but exclaimed to during periods of distress. Although the ancestors play an important role in their belief system, as do certain lesser spirits, religion concentrates on a pantheon of deities known as orisha. These are countless and vary considerably from area to area. A natural feature–hill, rock outcrop, stream–may be anthropomorphized and known by name in one community, and unheard-of five miles away. There are, however, orisha with a greater geographic spread and impact whose personalities and exploits are well-known (see some of them here: orisha chart). The orisha, though deities often associated with nature or natural forces, are conceptualized in human terms, and quarrel, love, and compete with one another. Their interest in human affairs is periodic, but they respond to sacrifice and request, and their devotees and priesthoods have been major patrons of Yoruba art.

We have already touched on certain major Yoruba religious concepts and related art forms in this book: divination (Chapter 3.6), witchcraft and its associated gelede masquerade (Chapter 3.3), the importance of twins even after death (Chapter 3.7), and egungun ancestral masquerades (Chapter 3.7). We’ve also examined other Yoruba art forms, including the Ife bronzes and terracottas (Chapter 3.8), kola nut presentation bowls (Chapter 1.3), Osugbo Society brasses (Chapter 3.2), and other sculptures and textiles. This section will concentrate on certain underlying religious concepts that manifest in traditional art and interactions with it, as well as take a closer look at artworks related to a single orisha in order to better understand the complexity of the interaction of religion, art, and life.

The Inner Head

According to Yoruba religion, we live cyclical lives. We await birth in the other world, the spirit world (orun), are born and become adults in this world (aiye), grow old and close to the ancestors, die and–if we have children who properly perform our funerals–become ancestors ourselves, only to face reincarnation back in our own family as the same gender. Our success in life is dependent on our head, an entity with two parts: the outer head (ori ode), supplied with a face for recognition, and our inner head (ori inu), the site of destiny and spirituality. Although

our inner head is invisible, the Yoruba conceptualize it as having a conical shape. Our good fortune and destiny in life come from our inner head, and our fortunes devolve on having a “good head” or a “bad head.” Our fate is our choice, however, for it is said we collect our head from the workshop of Obatala, orisha of creation (or, in some versions, the orisha Ajala Alamo, molder of ori inu), when we are still in the other world, about to be born. It is, however, a blind choice, for the exteriors of the conical inner heads look identical.

Personal shrines are prepared for individuals so they can honor their inner heads and sacrifice to them. Why? Even destiny is not completely fixed, but is more of a potential. Even a mediocre fate can be maximized through sacrifice, while the possibility of a splendid one can be achieved. Although fewer such shrines are created today, they are the sites of daily morning prayer. These shrines for the inner head are known as ibori, and are stored in larger, cowrie-covered leather containers known as ile ori (“house of the head”) (Fig. 545). The ibori is a small leather object that is also covered with overlapping cowries. These shells, imported from the Indian Ocean were the pre-colonial currency of most of Africa, so their presence honors the head with the personal sacrifice of money. The more socially significant the owner, the more elaborate the ile ori (Fig. 546). That of the Oba (the ruler) is beaded; the use of bead for clothing or accessories (other than necklaces and bracelets), is a practice reserved for the ruler or those to whom he grants the privilege.

Inside the conical ibori is fine sawdust or sand taken from a divination tray; it is all that remains of the sign the diviner marked when he marked the linear symbol for the Ifa divination verse that cites Ori, and absorbs the essence of prayers and incantations that dedicate the object and entwine it with its owner. The ibori is thus the visualization of the verbal, the ashe or power-to-make-things-happen of the object. Ashe is a key Yoruba religious concept; it is an empowering force found not only in life forms, but in certain inanimate objects, such as special stones. Ashe can be transferred from one being–human to human, human to

orisha or vice versa) through prayer and sacrifice. Sacrifices to one’s head can be simple–a kola nut, coconut water, sugar cane–or more expensive (a rooster or duck), the choice dependent on the situation and, perhaps, a diviner’s advice. The ibori in its ile ori is displayed next to the deceased, and carried in procession around town during a funeral, after which it is meant to be torn asunder, its pieces scattered on its owner’s grave, so close was their association.

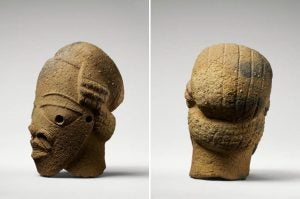

The concept of the inner head or ori inu is evident in many traditional Yoruba sculptures in two key ways. First, the head is given more prominence than other parts of the body, resulting in a head-to-body proportion that usually ranges from about 1:3 to 1:5 (Fig. 547) that honors the inner head, acknowledging its critical importance. Secondly, The hairstyle of many figures is elongated into a conical shape, acknowledging the inner, invisible engine that drives a person’s path through life (Fig. 548). This conical allusion also appears on formal royal beaded crowns (Figs. 549 and 550), dating back to the 19th century, and some metal crowns that are even older. While the age of the concept of the inner head is impossible to determine, it was in place in Ile-Ife (11th-15th centuries CE), for it shows as stand-alone cones with rudimentary linear indications of eyes and mouth–objects made at the same time as the highly naturalistic terracotta and bronze heads. One pot includes a relief of an altar with two conical representations flanking a naturalistic head, apparently a reference to the outer head, the inner head, and the absolute essence of an individual’s life made from primordial matter, known as oke ipori.

Yoruba art often alludes to sacrifice and transformation, both spiritually-linked practices. Sacrifice may be a personal practice to honor ancestors, deities, or other entities, or it may result from a divination consultation recommendation. Sacrifices usually consist of food or drink. The latter may be vegetable-based, such as palm oil for the orisha Eshu, or cooked white maize for the orisha Obatala. Others prefer meat, with chickens and goats being amongst the most common sacrifices; the colors and gender of these animals are usually prescribed by the diviner through the divination verses. While some sacrifices are left for vultures to consume, most are prepared as meals and shared with human attendees. In short, “animal sacrifice” is normally part of usual food preparation in agricultural surroundings, when having chicken for dinner means going

outside and choosing the chicken to be killed and prepared. The foods offered in sacrifice, however, are consecrated to their purpose through prayer and incantation, even when shared. A very common theme in Yoruba art, as we have already seen, is a woman holding or offering a chicken, and in these images (Fig. 551) we see a gesture of sacrifice, not one of simple hospitality.

Witches

Yoruba beliefs encompass the ability to transform, a skill limited to those with powerful supernatural abilities, such as rulers, priests, and witches. Although transformation can include other animals, these “night people”–for that is the time they accomplish their work–are said to remain in bed but send their spirit out in the (usually) guise of a bird or bat. Witches are particularly known for this phenomenon; although a male witch must be part of a group, most of a circle’s members are female. They meet at night in particular trees and consider their actions. Witches are considered in the main to be particularly wicked individuals, for they usually harm those they are related to, particularly their favorites. While an ordinary person may conceive of a wicked deed and execute it for reasons of greed, lust, or rage, these are understandable (if not condoned) actions. A witch, on the other hand, inflicts harm or death for anti-social reasons. They become witches either in the womb, because of their mother’s membership, or because they have eaten–intentionally or inadvertently–witchcraft medicine. They are considered particularly powerful beings, close or equivalent to the orisha in their abilities, and they are a stock component in Yoruba films and television shows (Fig. 552).

In much of Yorubaland, witch-inflicted matters are counteracted by the priests of Osanyin, orisha of healing and forest medicines. While these priests can “fight” the witches in the spiritual plane, they more often work for their clients by buying off the witches through sacrifices left at crossroads. In their diagnoses, they use small puppets within a darkened room, using ventriloquist skills to speak in Osanyin’s squeaky voice. Their consultation buildings are marked with short iron staffs that depict clusters of birds (Fig. 553). These represent covens of witches, the bird in the superior position indicating the Osanyin priests who share their skills to triumph over them.

In southwestern Yorubaland, in both Nigeria and the Benin Republic, a secular masquerade known as Gelede is meant to entertain and amuse the witches so that they will leave the community in peace. A particular

fear is that witches will “close the womb,” preventing procreation and village survival, so placating “our mothers” (witches are known by this flattering honorific) is essential. The performance has a sacred aspect in that divination is employed to select a propitious date, and sacrifices are offered to Iyanla, the Great Mother, but the performance itself does not incarnate spirits. Instead, teenage boys play the roles of community members, occasionally individualized but usually generic. They do so by wearing headpieces on the top of their heads, their faces and necks covered by cloth they can see through. The headpieces take human form and often have elaborate superstructure, some with metaphoric meaning, others observable actions, people, or objects. The Gelede festival begins at night with the Efe masquerade, who chief appeal lays in its satirical verses that ridicule problematic individuals or actions. Representations of the Great Mother follow, her representations occasionally that of a post-menopausal woman with a “beard” representing the scant hairs such women’s chins can sprout, or a representation that alludes to transformations of witch into bird (Fig. 554).

The following day sees groups of performers, usually danced in identical pairs. Those performing females wear women’s clothes in Nigeria, usually over a stick tied around the buttocks in an attempt to round out their adolescent skinniness; carved breasts sometimes are added as well. The teenage boys imitate women’s dancing styles that emphasize hip and shoulder movements, to the often visible amusement of older women. The characters often depict market women bearing trays or bowls of food for sale, or carefully carved braided hairstyles that emphasize women’s beauty (Fig. 555), although motifs can veer into imaginative areas that, in the Benin Republic, can even include puppets (Fig. 556). Performers who act as men have a more vigorous stamping dress style, their costumes usually consisting of lappets not unlike narrower versions of egungun costumes; in the Benin Republic, Gelede “females” sometimes wear these as well. Their masks can represent “types” (Fig. 557), and can also encompass a full range of superstructures, including hunters (Fig. 558), orisha priests and worshippers (Fig. 559), musicians, and others.

Interaction with the Orisha

Orisha worship might include hundreds of deities, but religious actions did not mean interacting with all of them. Historically, families had a relationship with a particular orisha, and many family names reflect this: Ogunremi (Ogun–god of war and iron–consoles me), Fagboye (Ifa–god of divination–has taken a title), Oshundara (Oshun–goddess of the Oshun River–is good), or Shaningobiyi (Shango–god of thunder and lightning–gave birth to this). Having a family association with a deity did not necessarily mean regular worship sessions for all members. The head of the family might have made weekly prayers on behalf of its members, but otherwise family members might have attended their deity’s annual festival or sought out the priestess or priest at the town’s shrine to the deity in order to seek a particular favor.

Each deity had its own priesthood and separate shrine. While individuals knew of other deities and some of the stories involving them, they were not expected to have a comprehensive knowledge of all the deities, except for Ifa diviners who interpreted messages from the spiritual world. In turn, they did not necessarily know the details of every aspect of a given orisha–that was the responsibility of the priesthood.

Some individuals received a call to participate more closely in orisha worship and initiate into that deity. This vocation generally began with an illness that sent the afflicted one to a diviner who indicated the sickness was inflicted by an orisha (not necessarily the family deity) in order to send a message–a command–that the individual needed to be initiated. If this order was resisted, the illness would intensify until initiation commenced. Under the guidance of the priestess or priest of a particular orisha, the trainee would learn the praise songs and dances associated with the deity, the food taboos they would need to follow, the favorite delicacies and other sacrifices the deity demanded, and all necessary esoteric knowledge. At the completion of training, the actual initiation would take place: the head was shaved, an incision made at the crown, and powdered medicine inserted. This medicine allowed for the safe possession of the initiate by the deity under controlled

conditions. With the priesthood supervising, drummers would beat the rhythms of the particular orisha, the initiates would dance his or her rhythms, and the orisha would descend and “ride” the initiation, entering at the incision point and swelling the inner head. At this point, the initiate would settle into a trance and continue to dance, but in a transformed state as temporary host to the deity (Fig. 560). Those in attendance might ask for favors or clarifications of problems they were undergoing; the initiate would answer with the orisha’s voice. After completion of the ceremony, the initiate would emerge from the trance and be led away to sleep. As living–albeit temporary–vessels of divinity, initiates allow followers of a deity to be in personal communion with their orisha.

In Nigeria, initiates do not need to wear special attire for ceremonies beyond metal or beaded bracelets and necklaces. They do, however, often carry implements during their dance. Priests and priestesses, however, may wear more elaborate dress during a festival for their deity.

In the past, when orisha worship was ubiquitous, temples to various orisha might be seen scattered throughout a given town. They were usually structures arranged around a courtyard, the shallow altars meant solely for storage of objects belonging to the deity. Minor rituals might take place inside the temple, but major ceremonies took place in the streets in order to accommodate crowds. Sacred objects included containers with the sacred, hidden objects (often specific stones) at the shrine’s core, as well as carved figures representing priestesses and priests or petitioners presented as gifts or thanksgiving offerings. Orisha themselves were rarely represented, with the exception of Eshu, who appeared on Ifa divination trays as well as in marketplaces and shrine sculpture.

Shango and Art

The kinds of objects associated with each orisha include both generic maternity figures and items specific only to that deity. To provide a sense of the spectrum of Yoruba shrine art, this section will explore visual aspects associated with the worship of Shango, orisha of thunder and lightning, the deified third monarch or Alaafin of the city of Oyo, who had been a great warrior.

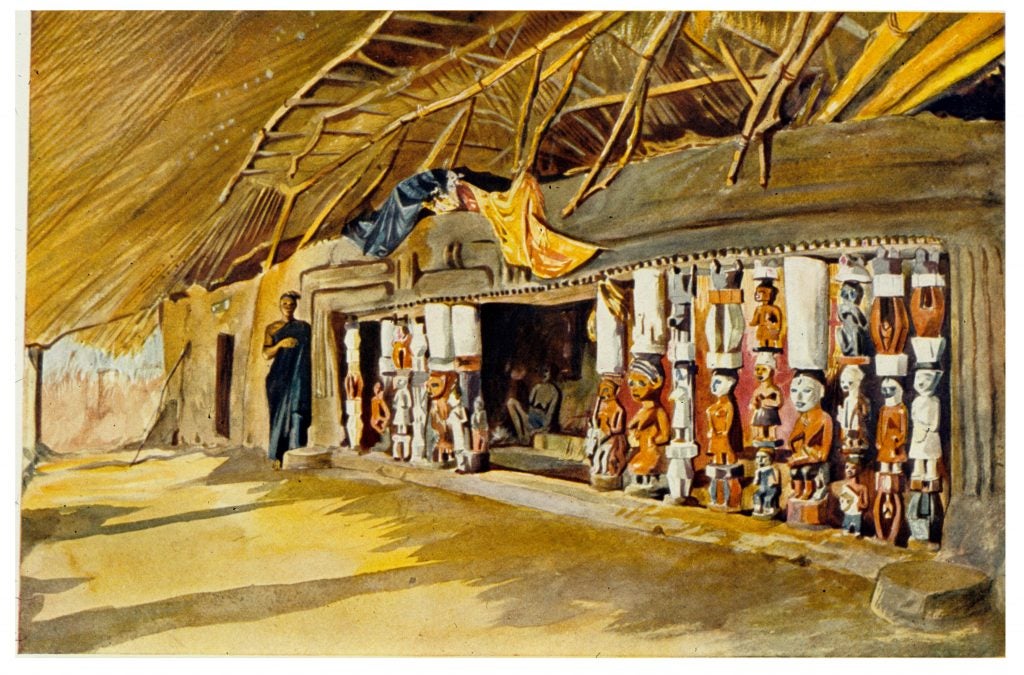

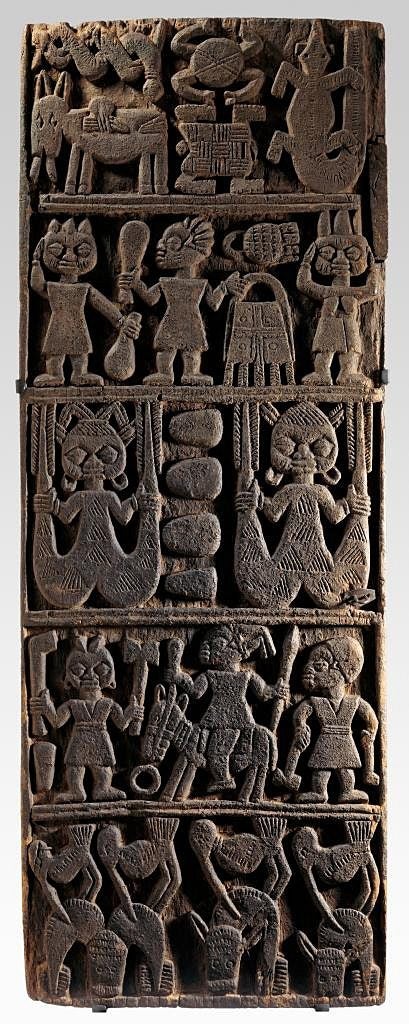

A Shango shrine like that of the city of Ibadan (Fig. 561) provides a sense of what these orisha centers once looked like. Originally its street facade included a relief-carved door (Fig. 562), similar to those found in palaces. Its interior held a roofed courtyard with the shallow space that served as the shrine’s core. Its contents were partially screened from view by a series of figurative wooden posts (Fig. 563), most of which have since been replaced by copies.

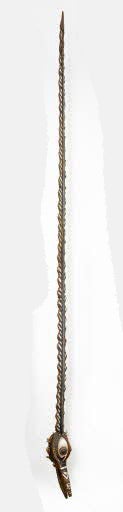

Appliqued leather bags (laba Shango) (Fig. 564) were hung from the lintel. These are carried by Shango priests during public ceremonies, as well as when they visit spots that Shango’s punitive lightning has struck. Such strikes are believed to be marked by “thunderbolts,” prehistoric stone axe-heads (edun ara) (Fig. 565). These constitute the key symbolic identity of Shango, the secret stones kept in the shrine; a water deity such as Erinle, for example, would have smooth river pebbles in his shrine containers. When Shango priests dig and discover thunderbolts, they can demand propitiatory gifts from the householder. The leather decoration of the laba Shango is abstract and consistent, full of energetic diagonals; the image may represent Eshu with his tailed headdress. The leather zig-zags at the bag’s bottom are said to represent lightning, and linear zig-zags appear in some other Shango objects.

Shrines include multiple types of works exclusive to Shango, such as the arugba Shango, a large female caryatid figure that supports a bowl that holds thunderbolts (Fig. 566). The odo Shango takes the form of a mortar–women pounding in a mortar create a thunderous sound–but it is always overturned, serving as a throne for

Shango to seat himself (Fig. 567); relief carvings on its surface are positioned to be upright when it is upended.

One unusual arugba (Fig. 568) shows the supporting female figure seated on an odo Shango.

Various terracotta vessels are also placed on Shango’s altars (Fig. 569). Their iconography includes simple oshe Shango, the wooden dancewands used by priests and initiates when in trance, and returned to the shrine when not in use.

Actual oshe Shango can take simple forms or be figurative, the thunderstones emerging from the head indicating Shango has taken possession of an initiate or priest. The personification of the stones makes this clear; they often bear either ethnic marks (Fig. 570) or indications of eyes.

Dancewands carried in ceremony vary significantly in both style

and complexity (Fig. 571). They always include a doubled thunderstone, a pairing that may refer to the twins Shango engendered. Ibeji twin figures are frequently retired to his altars, and an unusual shrine figure combines the standard twin figure pose with the doubled thunderstones of dancewands, as well as additional thunderstones and doubled heads (Fig. 572).

During trance performances, initiates and members of the priesthood move the wands violently, then return to equilibrium, referencing the unpredictable strikes of lightning itself. Priests can also display startling feats that Shango enables: walk through or sit on an open fire without harm, eat or spit fire, carry fire on the head, or pierce their tongues or cheeks with a sharp stick. Male priests plait their hair like women, since they are considered brides of the deity, and their ceremonial dress can be elaborate, including cowrie-bedecked tunics and paneled skirts (Figs. 573 and 574).

Traditional religion has been steadily decreasing in Yorubaland, with both Christianity and Islam pushing it into the background. Belief in witchcraft, ritual medicine, and divination may not have diminished, but fewer people publicly identify with orisha workship.

Elsewhere in the world, however, the religion continues to grow. Like other Yoruba deities, Shango came to the Americas as a result of the slave trade. His devotees in Brazil, Trinidad, and Cuba had to hide their religious practices but continued them nonetheless, sometimes disguising them behind a veil of Catholicism. In Cuba, for example, Shango is identified with St. Barbara, the 3rd century Greek virgin whose father locked her in a tower, and was struck by lightning

when he beheaded her for flouting his will and becoming a Christian. Containers for thunderstone are painted rather than carved in relief, and dancewands are no longer figurative, but red and white remain his sacred colors (Fig. 575). From Cuba, the religion spread to Puerto Rico and the United States, and the orisha–no longer hidden–have seen a growth in devotion throughout the Americas. In Brazil, even non-worshippers are familiar with Shango and the other deities, erecting public sculptures that honor their folkloric appeal (Fig. 576) in multiple cities.

In Nigeria itself, a prominent public sculpture also features Shango (Fig. 577). Created by an Igbo artist in 1964, it stands in front of the Lagos head office of the National Power Holding Company of Nigeria (formerly NEPA). The sculptor, Ben Enwonwu (1917-1994), was the son of a traditional artist and became Nigeria’s first contemporary art star. His training began under a British artist in Nigeria, and in 1944 he continued his training and education at multiple art schools and university, eventually receiving major commissions from Queen Elizabeth and the Nigerian state. Equally comfortable in realistic and abstract modes, he favored the former in his work Sango, which shows the muscular god holding his dancewand aloft, the crown that marks his kingship following the pattern of early crowns known at Ife.

Further Reading

Abiodun, Rowland. Yoruba art and language: seeking the African in African art. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Abiodun, Rowland, Henry J. Drewal and John Pemberton, eds. The Yoruba artist: new theoretical perspectives on African art. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994.

Awolalu, J. Omosade. “Yoruba Sacrificial Practice.” Journal of Religion in Africa 5 (Fasc. 2, 1973): 81-93.

Drewal, Margaret Thompson. “Projections from the top in Yoruba art.” African Arts 11 (1, 1977): 43-49, 91-92.

Drewal, Margaret Thompson. Yoruba Ritual: Performers, Play, Agency. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991.

Drewal, Henry J. and John Pemberton with Rowland Abiodun. Yoruba: nine centuries of African art and thought. New York: Center for African Art, 1989.

Fagg, William B. and John Pemberton. Yoruba, Sculpture of West Africa. New York: Knopf, 1982.

Lawal, Babatunde. “Orí: The Significance of the Head in Yoruba Sculpture.” Journal of Anthropological Research 41 (1, 1985): 91-103.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Black Gods and Kings [1971]. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1976.

Westcott, Joan and Peter Morton-Williams. “The Symbolism and Ritual Context of the Yoruba Laba Shango.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 92 (1, 1962): 23-37.

Wolff, Norma H. and D. Michael Warren. “The Agbeni Shango Shrine in Ibadan: A Century of Continuity.” African Arts 31 (3, 1998): 36-49; 94.