This chapter will focus on the early development of the domestic automobile industry highlight some of its earliest economic and financial accomplishments, as well as some of the business failures that helped to shape this most unpredictable national industry. It will also demonstrate how those changing economic and financial forces shaped the business agenda for manufacturers and distributors alike right to the present day. As we already know, there are thousands of dealerships trying to sell numerous cars to as many customers as possible. That means that individual outlets to ensure the kind of sustained profit margins required for long-term economic and financial success must exercise extreme caution in determining which car brand or brands they might want to carry in their showrooms. The business uncertainties, inherent within the automotive industry itself, and the buying public’s capriciousness, made worse by the uncertainties continually plaguing the national economy, often play havoc when it comes to choosing one brand over another.

This important decision-making process becomes even more traumatic for those automobile manufacturers with dubious business reputations based on less than sterling sales records. Realizing the conceivable economic drawbacks involved in both selling and servicing certain automobile brands, and most especially those major companies with only marginal profit potential at the present time, prevents many locally based dealerships from handling certain kinds of vehicles. Even highly respected domestic automobile companies may on occasion face bleak economic prospects especially if one or more of their current lines should suddenly fall out of favor with the buying public. Saturating the local market with certain brands, within tightly held price ranges, may also adversely affect the bottom line. No expert can predict, with any degree of accuracy, as to which car brands will sell well over the long haul, and which ones will succumb to the overwhelming business pressure exerted by vigilant competitors. Business uncertainty often places dealers in an economic quandary regularly.

If any doubts presently exist in the minds of today’s distributors regarding the best way in which to assure sustained new car sales, lurking competition emanating from other local franchises only adds to their intensifying business anxiety. Affiliated and non-affiliated dealerships know they must continually compete against each other for the same group of customers, whether they like it or not. Successfully incorporating a no-holds barred approach towards auto sales, whereby dealerships condone virtually any kind of brash business tactics used to secure new customers, often becomes the deciding business factor that may make or break a distributor. Those dealerships that win out often dominate the local market for a long time while, while those unable to withstand the economic pressure placed on them by competitors soon disappear. Few distributors are immune from such fierce competition due to the local economy that is always in a state of flux. Survival of the fittest best describes this phenomenon.

This nation’s love affair with the automobile began almost 130 years ago with the arrival of the first horseless carriages. Whether electric, steam or combustible gasoline-powered those contraptions quickly won the heart of the American people. They provided drivers and passengers a new sense of both adventure and freedom. It would only be a matter of time before automobiles would dominate our nation’s many byways and highways. As early as 1895, domestic automobile manufacturers recognized that their economic future rested on successfully bringing together three crucial elements. First, they must be able to manufacture enough automobiles to meet current demand, while at the same time, furnishing a sufficient supply of accessories and spare parts. Second, they must periodically update their body designs and improve performance. Third, they must have the capabilities of marketing their automobiles nationwide 24/7. Successfully accomplishing all three elements would inevitably separate the winners from the losers. Fortunately, many early manufacturers, respected mechanics and tradesmen in their-own right, possessed remarkable business skills when it came to manufacturing and distributing their-own vehicles. Most believed that their resiliency, as reflected through their unique entrepreneurial approach and unbending spirit, would see them through even the worst economic times. The fact that, in the early years, most carmakers sold everything they manufactured seemed to lend further credibility to this widely held belief.

In reality, early successes in the field, based almost exclusively on business ingenuity and luck, often lulled car producers into a false sense of optimism and security. Domestic auto manufacturers firmly believed that with the help of their competent work force they could survive even the worst economic disasters. Their assumptions were correct to a limited extent. Many early automakers not only remained industry leaders for years; but also, frequently dictated what the buying public could or could not purchase from them at any given time. They controlled early buying habits for two very important reasons. First, well-heeled investors afforded those car manufacturers great financial latitude when it came to making important business decisions affecting the future of their companies. The continued stream of new capital coming into their respective companies from those targeted investors enabled them to tighten or loosen their strangle hold over the buying public depending on current economic conditions. Second, the buying public, in the early years, would never have thought of challenging corporate decisions, at least not directly. After all, any challenge to the status quo might bring into question the innate value of those handcrafted vehicles along with the unquestionable right, on the part of the automobile producer, to charge whatever it considered necessary to improve its vehicles.

In a similar vein, early car owners often extolled the many virtues of specially tailored production methods over the less than perfect assembly line practices expounded by enlightened early 20th century manufacturers. The majority of buyers continued to adhere to that proven business principle in spite of the additional costs entailed in buying such finely crafted vehicles. The high cost of auto production, in conjunction with the many market uncertainties of the early 20th century, gave domestic manufacturers a decided business edge when it came to automobile choices, distribution and pricing. In essence, early domestic producers had deceived the buying public into believing that the entire financial risk entailed in the manufacturing and distributing of automobiles rested solely in the hands of the carmaker, and therefore, they should be the ones and not the public who determines which auto they should peddle and at what price level. The growing number of quality highways nationwide lent support to their arguments.

It was most definitely a sellers’ market in the early 20th century as reflected by the limited number of models offered annually. The very idea that the domestic automakers might offer a wide array of well-equipped models in a multiple of price ranges rarely, if ever, entered their minds then. Furthermore, manufacturers never envisioned the day when their customers, through their keen knowledge of the inner workings of the industry, would compel them to provide a wide assortment of new models in different price levels. Many automobile pioneers also failed to consider the possibility that their loyal customers might want to purchase new cars every three to five years rather than once a decade. However, all those things and so much more unfolded on the brink of the First World War. Aggressive competition, throughout the 1920s, compelled most manufacturers to initiate intermittent style changes and improve engine performance in order to enhance new car sales. They also began to offer vehicles in a multitude of price ranges. Pioneers in the automotive field, for the first time ever had to face the economic downside of this rewarding industry. Escalating overhead expenses and rising labor costs prompted a brand new kind of rational business thinking. Reoccurring problems related to balancing the budget increasingly concerned them. Their response to this growing financial dilemma varied greatly depending on the car make involved. At the outset, many luxury carmakers seemed to be able to weather the economic storms of change with relative ease. Their hard fought reputations for business excellence appeared to serve them well. After all, if a customer wanted a certain luxury brand then that individual must expect to pay the high costs of owning and operating such a prestigious vehicle. It was as simple as that.

Many lower priced vehicles also sold well in the 1920s due to the ability of those auto manufacturers to keep their overhead costs down, while sustaining high new car sales. However, the same positive economic scenario did not occur for moderately priced domestic cars. Enmeshed in a heated battle with other middle priced carmakers, many succumbed to the growing economic pressures of the day. The plethora of similarly equipped, middle priced autos posed a special problem for lesser-known makes who found it increasingly hard to sustain their-own customer niche. The Great Depression of the 1930s only magnified this urgency on the part of middle priced domestic auto manufacturers to find their proper place within this shrinking market. Yet, in spite of this growing dilemma, the industry somehow managed to move forward. However, not necessarily in the way experts had predicted in the 1920s. Rather than embracing the top quality, middle price automobiles that had made their mark during the Jazz Age, the buying public of the 1930s often rejected them. The explanation for this turnaround was quite simple. Instead of remaining a wide-open seller’s market, predicated on the desires and needs of successful carmakers, traditional creditors, wealthy speculators and affluent car buyers, the domestic automotive industry of the 1930s shifted its business focus. It became a buyer’s market controlled by an ensconced group of financiers. These titans of industry had the financial where-for-all necessary to control every aspect of the business at that juncture. The evolving car market of the 1930s catered almost exclusively to customers with large amounts of available cash. No one else truly mattered.

Undoubtedly, the 1920s represented a pivotal decade in the early history of the domestic automotive industry. Pioneers in the field with a dependable market of buyers and well-heeled investors persevered, while those on less solid economic footing yielded to changing conditions. If, in fact, the decade of the 1920s represented a defining moment for the young auto industry, then the decade of the 1930s represented the great leveler. The Great Depression of the 1930s was like no other economic calamity this nation had previously experienced. It was a complete and total breakdown of the American economic system, as we knew it then. In terms of the auto industry, it led to the demise of many of the oldest, most respected carmakers. Those car producers able to survive this unprecedented economic reversal either reduced their labor force significantly or stopped production often for indefinite periods. These latest strategies symbolized a major departure from the past when bourgeoning new car sales, resulting from carefully orchestrated business maneuvers, had successfully offset mounting labor and overhead expenses. Selling a bare minimum of automobiles to stave off increasing numbers of creditors no longer worked as more veteran carmakers closed their operations. Those enduring this extraordinary economic nightmare had somehow managed to meet the many business demands placed on them, but just barely.

The severe economic downturns facing U.S. business in the 1930s had very little to do with the dependability of the vehicles manufactured. The majority of domestic car companies, from the very beginning, had prided themselves on the high quality vehicles they produced. They also knew that possessing the business capabilities to sustain a large, nationwide distribution network represented the key to long lasting success. The nagging question facing many, in the earliest years of this budding industry, concerned the best ways in which to advertise their many products. At the turn of the 20th century, the majority of business leaders had their-own perspective as to what constituted effective advertising. Many experts in the field argued that word of mouth symbolized the most effective way in which to deliver their message. Small town merchants and large urban factory owners concurred with that thinking. The sustained financial success enjoyed by many domestic department stores, medium-size grocery stores and small independent shops, prior to the First World War, supported that notion. The Multiplier Effect certainly applied to both large and small retailers in those halcyon days.

Relying on local newspapers and regional magazines to sell their products also proved to be a very effective marketing device. Those media outlets not only provided an effective platform in which the manufacture could describe, often in painstaking detail, the various automobiles they were selling; but also, a place for them to display their products through a combination of beautiful drawings and black and white photographs. The quality of newspaper and magazine print also improved. Adding into this mounting success formula such things as catchy phrases and slogans helped the buying public considerably when it became time for them to choose their next auto. Popular slogans ran the gamut, from “Gardiner, The Guaranteed Car,” “Packard, Ask the Man Who Owns One” and “Suddenly its 1960, the all-new 1957 Plymouth” to “See the U.S. in Chevrolet,” “Don’t Experiment Just Buy a Ford” and “Durant Just a Real Good Car.” Slogans, throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s, emphasized both quality and value. “Oldsmobile By Every Measure…The Value Car of the Medium Price Class for 1959” and “Only the Sales Leader can give Sales Leader Savings,” a popular slogan to promote the all-new Ford for 1960, reflected this latest approach towards winning over the buying public. [1]

The idea of utilizing phrases and slogans began as early as the 1910s when the Stearns Company claimed to be “the Ultimate Car.” [2] Cleveland’s Fidelity Motors, at 2304 Euclid Avenue, describe the Moline as “the Quietest Car in the World.” [3] Chandler Motor Car Company referred to itself as “The Car with the Marvelous Motor” in 1914. [4] Individual car dealerships also developed their-own distinct slogans. Regal Motors, Cleveland’s oldest Nash dealership, reminded its many customers that “Our Reputation Is Your Guarantee” or “You Have Seen the Rest Now Look at the Best!” Shaker Heights Buick located at 3393 Warrensville Center Road. [5] Cleveland’s Bass Chevrolet ushered in the 1960s by proclaiming, “Every Day is Sales Day.” [6]

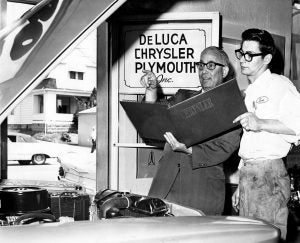

In the mid-1970s, one of Cleveland’s longest and most respected dealership Marshall Ford came up with the perfect catchphrase “People who start with Marshall Stay with Marshall.”[7] “We Have Buying Power for You” became a popular slogan for DeLuca Chrysler Plymouth, Glavic Dodge east and west and Mid Park Chrysler Plymouth. [8]

Hal Artz Lincoln Mercury, in the 1980s, described his dealership as the “Showplace of Beautiful Cars.” More recently, the Spitzer group used the following “Our World Revolves Around You.” Roadside billboards and large colorful posters prominently displayed on the sides of prominent commercial buildings symbolized other ways in which advertising firms promoted domestic cars throughout the second half of the 20th century.

The development of radio advertising, by the mid-1920s, followed by the advent of television, in the late 1940s, added an entirely new component to more traditional advertising ploys. Over the last thirty years, computer-generated advertisements have furnished yet another outlet for articulate advertisers to present their wares. Today’s carmakers worldwide spend $8,000,000,000 annually in various forms of advertising. Enumerable manufacturers and local distributors now turn to modern-day digital advertising platforms to discuss the many economic and financial benefits of leasing or owning their latest automobiles, trucks, SUVs and vans.

Conventional forms of advertising may have worked very well when promoting low cost items such as candy, cigarettes, bathroom products, cosmetics, dress-ware, food products, jewelry and shoes. Unfortunately, they did not fare as well when applied towards high threshold goods such as automobiles, appliances and furniture. Regular forms of advertising may have stirred up a limited amount of interest with certain, high priced items; however, when it came to purchasing the most expensive commodities sellers had to offer much more than everyday humdrum publicity pitches. Most often, that kind of selling required carefully orchestrated negotiations that involved both the distributor and buyer. That realization did not escape the attention of sharp 19th century domestic department store owners who wasted little time before introducing their own negotiating process. The key to selling a high threshold item did not depend on the product’s innate quality or potential usefulness, that was a given from the start. The biggest single issue confronting the seller and buyer when it came to purchasing that kind of high end product was not its cost; but rather, a hesitation on the part of the customer to pay the full asking price at purchase time. Installment buying, whereby the purchaser paid a reasonable amount of cash upfront in the form of a down payment followed by realistic monthly payments that included incurred interest until the debt was fully paid, seemed the perfect solution in that everyone got what they wanted.

However, in the event that a buyer dodged his or hers monthly payment obligation then the retailer had the authority to repose the item in question. This kind of intense negotiating required a certain amount of finesse on both sides. Buyers fully knew what they wanted, and how much they were willing to pay for it. Conversely, retailers knew the actual value of the product they were selling, and the minimum price they would accept for it. In theory, favorable terms through installment buying would not only put a minimal financial stress on the buyer over the course of the loan; but also, furnish the retailer with an acceptable high profit yield in the end. All parties involved in the transaction knew exactly what was at stake.

By the early 20th century, well-trained salespersons in both major department stores and small retail outlets alike had devoted countless hours negotiating acceptable installment arrangements with shoppers wishing to purchase high threshold items. Outsiders marveled at how well they performed their task. Some leading department stores and mail order houses took this business approach to an entirely new plateau. They expanded their current list of high threshold products to include pre-assembled new homes as well as the family automobile. In the latter case, it began when a highly successful mail order house called Montgomery Ward started selling its-own special vehicle in 1896. Called the American Electric, corporate officials touted it as safe for women. Regrettably, this car sold poorly, and Montgomery Ward stopped carrying it in 1902. Montgomery Ward re-entered the market, a decade later, when it sold an entirely new entry known as the Modoc. The company dropped this four-cylinder vehicle less than two years later. Sears & Roebuck sold its own brand of automobile beginning in 1908. Called the Motor Buggy, it cost only $395. (Figure 6) Sears sold 3,500 of them over the next five-year period. That same national retail chain, in 1952 and 1953, sold the Kaiser-built Allstate car for $1,395. Unfortunately, the company only built 1,566 of them.

A number of successful pioneers in the field such as Charles Duryea (1861-1938) and Frank Duryea (1869-1967) started advertising the many economic advantages of owning and operating their vehicles by the mid-1890s. Advertisements found in Horseless Age (1896) and Scientific America (1898) emphasized their never-ending personal commitment to product excellence. They firmly believed that their many satisfied customers spoke volumes about the inherent value of their cars. With the intention of reaching an even larger customer-base nationwide, a group of highly energized promoters sponsored the first domestic automobile show in 1900. Modeled after a similar exhibit successfully held in Paris two years earlier, New York City’s Madison Square Garden hosted this milestone event. It spotlighted more than 70 brands of domestic automobiles.

Its success prompted similar auto shows in Chicago, IL and Detroit, MI. The Cleveland auto show debuted at Gray’s Armory in 1903. This event featured about 75 vehicles, some manufactured in the city of Cleveland. [9] Proclaimed the Motor City by the local press, Cleveland retained that prestigious title until 1908 when Detroit, MI took over production reigns. The Cleveland Automobile Dealers Association CADA), founded in 1903, dedicated itself to promoting the local auto industry through special promotional activities that ranged from contest and parades to celebrated shows and demonstrations. The CADA evolved into the Cleveland Automotive Trade Association (CATA) by 1915. Over time, this popular organization provided an increasing number of worthwhile services including educational programs and philanthropic help. The modern-day Greater Cleveland Automobile Dealers’ Association provides a host of products and services geared for the needs and wants of its nearly 300 members. [10]

Early auto shows, like those held in Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit and New York, soon became gala events often lasting for more than a week. Not only did promoters encourage their ticket holders to inspect the various vehicles on display; but also, to pay special attention to the manufacturers as they described their latest engineering advances, newest safety features and unique body styles. The automotive industry repeatedly relied on these well-publicized events to promote their cars. Advertising agents did their part by guaranteeing that those events received the kind of extensive coverage they deserved from local newspapers, national magazines and wire services.

The popularity of these automobile shows led to extensive nationwide advertising campaigns. As early as 1910, domestic automakers spent more than $1,000,000 in advertising a year. Leading magazines of that period such as the Saturday Evening Post and McClure’s Magazine extolled the many practical benefits of owning and operating domestic vehicles. Those advertisements often emphasized such things as agility, durability, efficiency, speed and style. In addition, many of these well-articulate promotional pieces often focused on such things as affordability, dependability and prestige. Endorsements by famous celebrities and heroes and the public’s fascination with the open road stimulated new car sales even further. Today’s auto manufacturers still rely on some of the same advertising ploys first utilized to entice the buying public over a century ago. Today’s advertisements, like those in the past, often expounded the endless economic, financial and social values of driving a particular kind of automobile, pickup truck or van. Practicality and prestige, as well as price and maintenance cost, still influence buyers, choices.

Setting aside the successful advertising campaigns and spectacular auto shows in the early years, one of the major business dilemmas confronting virtually all domestic automakers, at the turn of the last century, involved product distribution. Specifically, how might these enthusiastic car producers efficiently deliver their many vehicles to customers without incurring unsightly additional costs? Auto manufacturers were not alone when it came to instituting new ways in which to supply their very special commodities. Similar distribution issues plagued other large domestic industries as well. Much of the quandary originated in the nature of the product itself. Surprisingly, that issue never arose with earlier, less sophisticated cottage-based industries. Those high–prized items nearly always sold regardless of market conditions. Perhaps the practicality of those handmade items, more than any other single factor, made them indispensable to the public regardless of the current economic climate.

Whatever the particular reason for their continued financial success one thing remained true. The many skilled artisans involved in cottage industries possessed a special business knack of passing on any additional costs incurred during production to the buying public with virtually no protest. Unanticipated business entanglements or erratic markets rarely affected sales. Undaunted high demand for what they produced ensured a ready-made market at all times. In those rare instances when inventory might have surpassed demand, individual artisans might choose to merge their operations with a competitor or close down temporarily. Remember the majority of those artisans sold their items directly to the public through their-own small shops. No frill sales meant that their overhead costs not only remained modest when compared to modern-day expenditures; but also, enabled most of them to suspend production for up to a year without experiencing any permanent profit loses from such action.

Those investing in the mid-19th century American textile industry, unlike earlier highly successful cottage-based industries, could not exercise such leeway. They were anything but assured of a free-flowing, low cost distribution network that could easily sell their many items to an awaiting public regardless of current market conditions. In many ways, the 20th century automotive industry more closely emulated the textile mills rather than earlier cottage industry models. Like textile factory owners, automobile manufacturers were compelled to seek out new customers regularly in order to remain economically solvent. They also had to convince that same group of buyers that their products were far superior to other brands readily available in the open market. The emergence of the domestic textile industry not only led to significant changes in terms of marketing strategies; but also, markedly altered generally accepted business rules that eventually affected the auto industry.

In the case of the 19th century textile operators, the financial uncertainties resulting from worsening overhead expenses and fluctuating cotton crops from the antebellum South did not allow a more nonchalant approach. Relentless competition from ruthless outsiders motivated much of their daily actions even when that resulted in over production one year and noticeable shortages the next. The economic quandary, they first experienced in the 1820s, became even more acute by the mid-1830s as those same mill owners continued to produce thousands of bolts of cloth annually for an increasingly saturated market. These entrepreneurs needed to find a way to shore up their financial holdings quickly as a way of covering up possible future losses should the market for their products suddenly disappear due to either unexpected competition or major technological breakthroughs.

New economic prospects, in the late 1840s and early 1850s, convinced many mill owners to manufacture their-own ready-made garments. However, this revolutionary development in itself did not guarantee sustained high profits for those individuals brave enough to embark upon these new, unchartered economic waters. In fact, the real possibility of bankruptcy looming over their heads prevented some mill owners from straying away from the norm. The prevailing business wisdom of the pre-Civil War era strongly suggested that local market conditions, more than any other single economic factor, determined ultimate financial success or failure. Innate know how, on the part of the mill owners themselves, along with some luck and outside capital remained essential business components in any successful venture of that nature. However, grim those economic prospects might have seemed during the late 1830s and early 1840s that did not stymy enterprising textile owners from taking charge of the situation whenever the opportunity occurred. Selling pre-made clothing, within an expanding market place, was not an undertaking taken by the faint of heart. Those venturing into this new speculative business realm could not rely on successful retail models, of the recent past, to guide them through it. Those models did not exist.

Small urban retail shops, many operating with little or no cash reserves, often turned to business intermediaries for assistance. Known as jobbers, they furnished many conventional retailers with what they thought were potentially very profitable items for their many stores. Pre-determined commissions decided the extent of a jobbers’ involvement in this process. In large cities such as Boston, New York or Philadelphia, some department stores enticed shoppers into their premises by using an even simpler business approach referred to as consignment. Operating company-owned retail outlets symbolized another option for mill owners wishing to sell their ready-made merchandise. However, the high costs of maintaining a chain of company stores made that idea less and less appealing over time.

Recognizing the importance of acting quickly if they hoped to profit handsomely from this growing demand for their clothing, led the majority of those factory owners to choose the consignment method of sales. It involved the least amount of business risk. Under this arrangement, textile representatives designated certain successful clothiers to sell their ready-made garments. Participating mills shared a small percentage of the profit derived from selling those items with those respective retailers. Consignment eliminated much of the added overhead expenses inherently associated with retailing. Furthermore, it ensured mass distribution of their products as well as a permanent market for selling their merchandise. Participating retailers used this new opportunity to advertise the uniqueness of their individual stores. Over the long haul, consignment represented a win-win situation for all involved.

Ready-made clothing sold remarkably well especially during the Civil War. The union army increasingly required ready-made uniforms produced by those Northern mills. The proliferation of successful clothing manufacturers in Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, New York, Philadelphia and St. Louis immediately following the Civil War era attested to the earlier financial gains accrued by successful East Coast textile owners nearly everywhere. Mill operators used their newly acquired wealth to invest in other, equally lucrative opportunities throughout the Gilded Age. A similar story unfolded within the domestic auto industry at the turn of the 20th century. At first glance, any business similarities between those two industries may seem somewhat far-fetched. After all, the 19th century textile industry prided itself on its ability to manufacture and sell a wide assortment of inexpensive goods within a relatively stable national economic environment, while early 20th century automakers manufactured and distributed various priced vehicles within a highly volatile business climate.

On a superficial level, these marked contrasts appeared to take precedent over any other possible connections or business similarities. However closer scrutiny suggests otherwise. Certain overriding business factors imply a direct correlation between those bourgeoning industries. The buying public seemed to acknowledge that inter connection early on, and praised both groups for their ability to not only successfully market their-own products on a sustained basis; but also, embrace the many technical advances equated with the phenomenal growth and unpredicted changes associated with both eras.

Manufacturing a dependable, safe product at a reasonable cost was one thing, but being able to successfully marketing it annually was truly amazing. The economic complexities in marketing high threshold items, based on accepted late 19th century retail practices, did not seem feasible to the emerging auto industry. However, a more in-depth investigation strongly supports the notion that the phenomenal, long-term economic and financial success enjoyed by the textile and automotive industries respectively rested on two interconnected vital components: sales volume and repeat business. In both case, a wide distribution network represented the best possible solution even if their individual business approaches and challenges may have appeared quite different. The highly prosperous late 19th century domestic retail sector, through consignment, had welcomed the prospects of selling even greater amounts of affordable ready-made clothing as that century unfolded. Profit seemed to abound for all parties involved due primarily to recently perfected production and distribution methods. However, that did not occur as rapidly for the domestic auto industry. The increasing costs incurred in manufacturing and shipping new cars to consumers only worsened over time due in large part to the plethora of domestic manufacturers each vying against the other for the same group of customers. Obviously, most producers did not cherish the idea of offering a limited number of customers a wide assortment of car options. Fewer choices, from a select number of locally based producers, would have been much more profitable for the remaining manufacturers in that it would have lowered production and distribution costs over the short haul. Other problems related to safely operating vehicles, along with the daily routine of maintaining new and used automobiles, also faced this embryonic industry.

During the first two decades of the 20th century, widespread business experimentation became the rule, not the exception, with the majority of domestic automobile leaders. Maximizing profits, while minimizing overhead expenses took top priority, as pioneers in the field sold the vast majority of their new vehicles through specially designated sales agents. They were not in the true sense jobbers or established retailers although many possessed some of the same business qualities attributed to both. Often local mechanics with recognized business sense, these highly enterprising agents, and not the auto manufacturers themselves, assumed the bulk of the responsibility for maintaining the many automobiles they sold. After all, frequent repairs required well-trained mechanics to be on call at any given moment.

As was mentioned earlier, the increasing number of new car orders, at the turn of the last century, all but assured profits for those fortunate automakers that had successfully fulfilled consumer demands for new vehicles with a wide range of options. Advances in assembly line production along with continual pressure for more quality repair service ultimately determined which producers survived this growing economic challenge and which ones succumbed to it. Without a doubt, effective car distribution and dependable repair service played indispensable roles in determining the outcome. Selling directly to customers, consigning to local department stores or operating company-run stores remained the three most viable options for domestic manufacturers at the turn of the last century. [11] The profits received by pioneers in this field varied greatly with much of it determined by local economic conditions and potential market size. In smaller communities, where profit margins were decidedly more limited, traditional marketing practices appeared to be the simplest way to sell vehicles. That business approach remained credible as long as the number of competitors remained contained. However, in larger market settings, where competition was far greater, such parochial practices gained few adherents.

Early leaders in the field such as Winton Motor Car Company held steadfast to the belief that company owned and operated branch shops represented the pragmatic solution to this ever-perplexing distribution problem. Only answerable to their manufacturers, those branch outlets would never desert to another automaker. [12] Winton Motor Car Company’s early advertisements underscored the fact that they wanted to please their customers, and that satisfactory repair service was their chief concern. [13] Many critics disagreed with that assertion claiming that most factory-owned stores relied almost exclusively on company salespersons and mechanics who frequently demonstrated a lackadaisical attitude when it came to serving customers. That obvious indifference often led to scores of complaints from many frustrated car owners. Apparently, salaried employees often showed very little interest when it came to selling and servicing vehicles. The idea that they might be creating a good paying, permanent career option for themselves, based on their special knowledge in this promising endeavor, never seemed to enter most of their minds. In 1910, George Kissel, the President of Kissel Kar, addressed that concern when he reminded everyone that his carefully chosen sales representatives were honest and that the high quality of his many automobiles spoke for themselves. [14]

There had to be a better, more efficient way in which to further new car sales, while at the same time adopting a positive business relationship with the buying public. Auto manufacturers concluded that franchising their car brand to local business leaders embodied a more even-tempered business approach towards this reoccurring problem. Entrepreneurial-inspired individuals, within this emerging business arena, would over time dedicated themselves to the communities they served. Investing their hard-earned dollars into these franchises might foster a wide array of new and resourceful business methods never envisioned previously by other, less inspired company employees. Their long-term economic survival as a business depended on individual franchises succeeding from day one.

If done efficiently and precisely, everyone investing in these recently awarded franchises would profit handsomely, if not, everyone involved would suffer similar financial losses, losses often made worse by poorly executed business plans. Running an effective car distribution and service operation required much more than just a lop-sided business agreement drawn up between an auto producer and dealer. Long-term success rested on establishing continual, meaningful dialogue between the manufacturer and its many distributors. Detailing the innumerable business privileges and legal responsibilities for all parties involved in this endeavor soon became the accepted way to conduct business throughout the industry.

In the early years, most car manufacturers and their dealers automatically renewed their contracts at the end of each calendar year. Those agreements not only detailed the many provisions individual distributors must follow; but also, addressed other pertinent issues such as new car inventory requirements, real estate prerequisites and staff qualifications. These contracts also specified procedures that affiliated dealers must abide by when purchasing and selling automobiles, accessories and auto parts.

The majority of these annual renewals also defined repair specifications and explained the finer points related to their particular automobile financing packages. Corporate headquarters made it quite clear that they alone reserved the right to cancel a dealer’s franchise anytime if for some reason they believed that the dealership, in question, had breached its contract.

As part of that tightly held agreement, distributors retained the right to retain legal counsel if they believed that the actions taken against them by their parent manufacturer were either unfair or unsubstantiated. However, their right to legal counsel did not, in any way, guarantee that the court would find in favor of them. Nevertheless, some dissatisfied local dealerships decided to fight back against what they perceived to be unscrupulous manufacturers by establishing their-own special lobbying group starting in 1917. Dedicated to the thousands of domestic dealerships, the National Automobile Dealers Association (NADA) provides its many members and the buying public germane information pertaining to both its dealerships and industry. [15] This 16,000-member group also deals with highway safety and environmental concerns. One of its first successes as a recognized lobbyist occurred in 1919 when the U.S. Congress reduced a proposed luxury tax on cars from 5% to 3%.

This legislative body further ensured that the auto industry would not lose a large percentage of its workforce during the First World War. NADA later successfully backed efforts making it a federal crime to illegally-ship automobiles across state borders. As a public service, NADA issued its-own blue book on used car pricing beginning in the 1930s. [16] J.D. Power took over the publication in 2015. In the early 1970s, the NADA board created the American Truck Dealers Association (ATDA). The ATDA, representing nearly 2,000 agencies, specializes in the selling and servicing of both heavy and medium-duty trucks. NADA’s charities provide its membership money and assistance in times of emergency. It has allocated more than $13,000,000 towards disable veterans and children with special needs. This organization also provides other community services including assist dogs.

The Kelley Blue Book represents another equally important independent research source dedicated to fair car pricing and valuation. Founded in 1926 by a California car dealer named Les Kelley, this invaluable source quickly became a standard auto price guide used by domestic dealers throughout the nation. It introduced its own website in 1995. Bought by AutoTrader.com in 2010, Kelly Blue Book became part of a Chinese internet provider and service group called Bitauto Holdings LTD three years later. Cox Automotive, a subsidiary of Cox Enterprises currently controls it.

Most early 20th century dealers agreed that the potential economic advantages of selling a recognized make of domestic auto far outweighed any special requirements or restrictions imposed on them by that specific carmaker. It would lead to hundreds, if not thousands, of new customers visiting their showrooms annually. That action alone would undoubtedly generate greater profit returns then would have been the case if they had chosen to remain independent. In addition, affiliating with a nationally recognized auto manufacturer would inspire better-qualified salespersons and mechanics to work at their various sites. This idea of direct association with a name brand product gained further credibility in 1917, when domestic car sales for the very first time topped the 1,000,000 mark. Customer-pull, a term used to describe the quick, turnover of new cars on a daily basis applied directly to affiliated dealerships where increasing repeat business promulgated consistently high profit returns.

The growing market for used vehicles was equally important. For example, one popular domestic automaker F.B. Stearns, as early as 1912, ran regular advertisements in the Cleveland Plain Dealer extolling the many advantages of purchasing that its used vehicles. These advertisements carefully pointed out that these select cars represented recent trade-ins for all-new Stearns-Knight automobiles, and that company experts had thoroughly examined all those cars. Interestingly, those same advertisements did not post prices.[17] Both Winton Motor Car Company and Peerless Motor Car Company offered similar used car deals early on. [18] Packard Motor Car Company, in 1915, went so far as to suggest that it was better to own one of its many high quality used automobiles than to buy some other company’s new vehicle at the same price.[19]

Studebaker Sales Company of Ohio, at 2029 Euclid Avenue, set another business precedent when it advertised a “trade-in sale” for new automobiles starting in November 1917. Apparently, the growing demand for quality used vehicles prompted this dealership to sponsor such an event. That would have been unheard of in the earliest years. [20] By 1915, used car sales advertisements featured both prices and mileage. [21] Chandler Motor Car Company advanced something new and different called “used car financing” in 1920. [22] Cleveland Cadillac took used car sales to the next level, two years later, when it proudly announced that it sold used cars primarily to stimulate new car sales and not for potential profit.[23] The three Cleveland-based Studebaker Corporation distributors offered quality used cars for a 30% down payment with no added brokerage fee beginning in 1925. The Jordan Car Company provided an even better deal for those customers interested in purchasing one of its used car offerings. That carmaker only required a 20% down payment with no interest or brokerage fee plus a special 90-day guarantee. [24]

Being a sellers’ market offered some unique advantages for those wishing to own and operate a dealership. There appeared to be only a minimum financial risk for well-managed dealerships, at least during the first two decades of the 20th century. This held especially true for investors with solid repeat business. In some cases, customer loyalty to a distributor took precedent over the make sold there. This was especially evident in the early years when dealers frequently changed brands or carried more than one make of car in their showrooms. [25] These new dealerships, with their new, highly energized models of corporate efficiency, appealed to domestic auto producers who wanted to concentrate more on overtaking mounting competition and less on the tedious task of overseeing each-and-every aspect of car sales and repair service in each of their many dealerships. [26]

Increasingly, manufacturers turned over to the simpler daily business tasks to their many affiliates. Corporate heads rightfully claimed that distributors enjoyed a business advantage over them when it came to handling local sales and service needs. After all, designated franchises worked directly with the customers they served. Being a recognized part of their community meant that their employees should be able to deal with simple, everyday problems that might arise. At the same time, manufacturers calmed the fears of their distributors by saying that they would intercede, on their behalf, whenever necessary.

Prior to the First World War, nearly every domestic car made sold very quickly. The high profit resulting from such rapid sales activity ensured the success of most local dealerships, at least for the interim. Fierce competition, from the 1920s onward, along with new, exaggerated manufacturing costs and expenses, made worse by unpredictable current market conditions, negatively affected many carmakers and their affiliates. Putting aside the public clamor for more high quality designed vehicles there were other equally important business changes at work throughout the 1920s. In particular, an industry-wide obsession now called for all car franchises to adopt the latest scientific approaches towards business. A closer look suggests that this new, far more advanced approach towards business, first initiated by enterprising domestic automakers in the 1920s, did indeed represent the next step in this evolutionary process. New, cost effective business methods changed everything.

Unfortunately, that business transition of throwing out the old for the new was anything but smooth for some producers. The reluctance on the part of many of the older manufacturers to discard their long held accounting methods, infuriated enlightened automakers who contended that modernizing business procedures were essential if this industry intended to grow and prosper in the future. With capital investment in manufacturing and marketing exceeding $2,000,000,000 by the mid-1920s, leading domestic manufacturers increasingly understood the importance of keeping pace with the many changing business standards. Smaller car producers might have agreed with their peers in theory; however, many expressed concerns that introducing such modern thinking so quickly might run contrary to their early, well-articulated business plans that called for conducting business as usual.

Escalating overhead costs led some traditional automobile companies to place much of the blame for recent declining sales on their affiliates that sold more than one name brand automobile. They said that split loyalties did not promote multiple sales for the leading brands. Many multi carriers contradicted that notion by saying that they consistently generated high profits, and that selling a single make of car, without the additional sales generated by unloading competing brands, would prevent them from attaining their intended high profit goals. Split loyalty coupled with a frequently saturated local market that often lowered the profit potential for each new car or truck sold, did not help deficit prone automobile manufacturers who were compelled to operate under very tightly controlled budgets. Many debt-ridden carmakers may have produced high quality vehicles at a reasonable going cost; however, if their methods of conducting business with both their distributors and the public failed to keep pace with the changing times then they too would soon lose their commanding edge.

Ultimately, many of the economic and financial spoils accumulated during the prosperous 1920s went towards creating efficiently operated assembly lines. This growing business trend affected nearly everyone in the industry regardless of the affordability or quality of the vehicles manufactured. Regrettably, that kind of business efficiency did not necessarily carry over to their affiliates. In fact, many of the most successful distributors, found in the nation’s large urban markets, offered a wide range of car models emanating from a host of competing companies. Bourgeoning business demands and a dwindling local market culminated in financial ruin for many smaller domestic manufacturers during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Losing large numbers of customers, at an alarming fast pace, compelled many auto pioneers such as Chandler, Jordan, Kissel and Mercer to succumb to the overpowering economic pressures of that era.

In the case of the Jordan Ohio Company, its many fine automobiles displayed at its beautiful showroom and distribution center, at East 46th Street and Euclid Avenue, during the late 1920s represented some of the best car values available in Cleveland. [27] (Figure 7) Their many high quality features ranged from an advanced silhouette, locked transmission and special chassis lubricating system to an all steel body, dependable 8-cylimder engine and an average of 24.1 miles per gallon on the open highway. [28] Unfortunately, the many fine subtleties of owning and operating a true masterpiece of auto engineering, such as the Model 8G/90, were soon forgotten based on a growingly despondent by the buying public as it faced the grim realities of the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Given the dismal business climate of the 1930s, it was surprising that many of the traditional economic and financial obstacles responsible for hindering future growth industry-wide, such as escalating prices and reduced volume, had only a minimum effect on determining the business fate of so many smaller car producers. The four automakers, mentioned above, sold more than a sufficient number of vehicles to remain in business during the economically turbulent 1930s. After all, their claim to fame, over the previous quarter of a century, had rested on their remarkable ability to sell high priced, quality automobiles repeatedly to their ever loyal, well-defined customer-base.

Unfortunately, unexpected outside economic pressures and powerful new business strategies adopted industry-wide ultimately forced their hand. Unforeseen economic twists and turns, throughout the prosperous 1920s, that ended with the devastating stock market crash in October 1929, marked the first in a series of major setbacks that culminated in their eventual demise.

Those automobile producers able to survive the initial on-slot of closings, in the early 1930s, soon found themselves acquiescing to the harsh economic realities of that era. That compulsion to alter long accepted business strategies quickly for some still undefined business approach came with a high price. With few choices available, most car manufacturers supported whatever economic changes industry-wide leaders might have endorsed at any given moment. The vast majority of auto producers rarely considered any of the long-term economic and financial consequences that such hastily conceived plans might have on their company’s ultimate fate. Economic survival remained paramount and everyone in the auto industry knew it whether they cared to admit it or not.

On a more positive note, the continual flood of worthwhile new approaches towards business that came across their desks encouraged many insightful domestic manufacturers to scrap their traditional corporate strategies and willingly experiment with some previously untested new methods. In fact, many of those tactics not only helped domestic carmakers to determine the best course of action to follow at least for the immediate future; but also, enabled them to weather the many new economic vicissitudes that had started to unfold. It forced corporate executives, in particular, to scrutinize in more detail their company’s recent new car sales activities. Their interest, in this regard, focused precisely on what action they might take immediately to increase new car orders, while eliminating overstock and improving their used car sales. Placing all three of those objectives into one single action plan symbolized a major advancement never envisioned by the automobile industry during the halcyon days of the 1920s.

Once these automakers had a clearer understanding, of their current financial situation and immediate economic prospects, then they could begin to remedy the many other issues they had previously overlooked. They hoped that their newly revised business plans would accomplish much more than just sustaining their corporation through the present economic and financial downturn. They wanted those latest corporate dictates to act as a catalyst for even greater internal business changes once prosperity returned. In the early years, domestic automobile corporations had relied almost exclusively on their knowledgeable accountants to develop and execute effective new business plans whenever economic conditions warranted such action. Now corporate executives were compelled to assist their able body accountants in initiating their latest economic goals and objectives without a plethora of well-established business models to assist them through the process.

Throughout the 1930s, many dealerships waited patiently to see what new business prerogatives might be forthcoming from headquarters. Mounting new car inventories added to their growing economic woes as the Great Depression of the 1930s exacerbated. First evident in the 1920s, high new car inventories symbolized the less desirable side of owning and operating a distributor. Dealers fully knew that sustaining large new car inventories might dramatically reduce profit potential and that if that problem persisted long enough then the variety and number of automobiles and trucks they could sell also would drop appreciably. Lack of car choices did not bode well for the future of car outlets in general, but most especially smaller ones. As the national economy worsened, it became even more imperative for distributors, both big and small, to significantly reduce their new car inventories as soon as possible or face the distinct possibility of bankruptcy.

The changing business relationship between local distributors and the buying public presented an interesting business challenge even for the most seasoned dealers. Customer loyalty, once viewed as fundamental to any successful affiliate, had all but disappeared by the mid-1930s. Tight money had changed the scope of everything. That meant that prospective buyers did not automatically purchase their next car from their local distributor. Instead, they shopped around for the best possible deal. A smart approach, it became even smarter, as dealerships tried repeatedly to cater to their dwindling customer-base. Updating traditional business practices, in an attempt to ensure sustained economic growth, was not something new. Shrewd automakers had always made it a practice to do just that. The unparalleled success enjoyed first by Ransom B. Olds (1864-1950) and later Henry Ford (1863-1947) demonstrated the crucial importance of reducing per-unit production costs whenever and wherever possible. Research and development represented the keys to long-term success and everyone knew it. In the early years that meant investing in the latest assembly-line techniques. Ransom B. Olds led the way when he introduced his-own assembly-line method in 1901. He based it on the slaughterhouse methods as perfected, in the 1870s, by Gustavus Swift (1839-1903). Called Progressive Assembly, it involved movable casters suspended from the factory’s ceiling. Placed at strategic locations throughout the building, those specially designed casters enabled autoworkers to engage in a multitude of assembly-related tasks each within easy reach on their workstations. Multi-tasking, like that, not only sped up overall production; but also, reduced the possibility of major assembly line errors. Most importantly, cheaper manufacturing costs resulted in greater profits. In the case of Ransom B. Olds, he dominated this field at the turn of the 20th century. (Figure 8)

Using his recently perfected production method enabled Olds to manufacture over 5,000 curved dashed models at $650 apiece by 1904. Other Oldsmobile models that same year included the touring runabout at $750 and light tonneau car at $950. Using fundamental mechanical and construction principles, Ransom Olds repeatedly produced reliable automobiles. [29] Other manufacturers, inspired by his phenomenal success, tried to improve upon his production methods with varying results. The Apperson Brothers Auto Company of Kokomo, IN, headed by Edgar Apperson (1870-1959) and Elmer Apperson (1861-1920), also enjoyed limited success. Those innovative brothers prided themselves on their high quality luxury cars that featured components and parts made in their-own factory. [30]

Henry Ford symbolized another of those enterprising manufacturers who wanted to carve out his own business niche during the first decade of the 20th century. He firmly believed that the buying public wanted an inexpensive, no frills automobile to drive on a daily basis. He was not alone in that thinking. Many other automakers recognized the phenomenal profit potential if they could successfully manufacture a high volume, low-priced vehicle. The idea may have been very sound in principle; however, as many investors soon discovered they had to confront the ever-present problem of mounting overhead expenses. Specifically, how could they keep their costs to a minimum, while maintaining the high volume necessary to make it successful?

Maintaining reasonable overhead costs also greatly concerned luxury auto manufacturers although it did not consume the bulk of their energy at the beginning of the 20th century. After all, they had certain marked business advantages over cheaper automobiles. Eager to own their cars, their wealthy buyers would assume any-and-all added costs that might occur during the production or distribution phases in the form of higher prices. Meticulously constructed automobiles made of the finest materials with the latest accessories and newest technology they were well worth the extra cost. Luxury car producers legitimized such actions by reaffirming that wealthy customers were the only ones who could afford their autos anyway. Those individuals unable to own and operated such prestigious vehicles did not purchase them, plain and simple.

As stated above, the successful production of an inexpensive auto depended on continual low overhead costs and high volume. That meant cutting financial costs whenever possible, while manufacturing dependable automobiles the public wanted to purchase. No small task to accomplish, Henry Ford eventually achieved that allusive goal, but not before enduring some major setbacks along the way.

Finally, he introduced his latest low cost model in 1909. Called the Model T, and priced just under $900, that latest entry into the bourgeoning 20th century domestic car market represented the reasonably priced auto most Americans wanted and needed. Limiting color selection, accessories and options enabled Henry Ford to keep costs down. The highly popular Model T changed very little over its 16-year run. Its dependability, durability and low cost spoke volumes about that automobile and the man responsible for manufacturing and delivering it. (Figure 10)

In order to expedite production, Henry Ford modified the assembly-line system as first developed by Ransom B. Olds. With specially manufactured tools, assembly-line workers at Ford Motor Company speedily completed their individual tasks at their designated workstations. Unlike the earlier models manufactured at Olds Motor Works in East Lansing, MI, where assembly-line functions would require workers to periodically leave their work stations in order to complete one or more tasks, this latest version of the assembly-line brought the product directly to the workers through a specially developed conveyor belt system. Assembly-line workers proceeded to complete their tasks, and then sent the partially finished automobile along the conveyor belt to the next workstation. That same process repeated itself hundreds of times daily. It took less than two hours to build a complete Model T. Henry Ford had indeed perfected the assembly-line process begun by one of his chief business rivals Ransom B. Olds. In order to guarantee a competent and reliable workforce, Henry Ford paid his workers an unprecedented $5.00 per day starting in 1914.

At the outbreak of the First World War, the intricate national network of Ford dealerships all but ensured future sales for all of Henry Ford’s automobiles, but most especially his top selling Model T. Well-defined business practices, originating from Dearborn, MI, helped Ford Motor Company sell large number of vehicles repeatedly. In fact, Henry Ford personally handled many of the minuscule details related to daily operations. Fortunately, the Model T, known for its durability and low cost, appealed to customers from all walks-of-life. In the early 1920s, nothing was-left to chance as Ford Motor Company dominated the domestic car market. The $8,000,000 acquisition of the Lincoln Motor Company enabled Ford Motor Company to enter the luxury market in February 1922. Ford sold more than 7,800 Lincolns the following year.

Had the Midwest based nationalist been less outspoken when it came to his-own personal prejudices, the Ford Motor Company might have remained the unchallenged leader of Detroit’s Big Three for many years to come. Unfortunately, Henry Ford’s unashamed prejudices, leveled explicitly against Jews, undermined his early lead. Some local Ford dealers tried unsuccessfully to minimize the negative publicity generated by Henry Ford’s uncalled-for actions. However, the word was now out, and it did not take long for the other two Detroit automobile giants to react. Henry Ford’s chief competitors in the form of General Motors Corporation and Chrysler Corporation responded quickly by presenting a full range of attractive cars in a wide assortment of colors, body styles and price ranges minus the prejudice. By the late 1920s, General Motors Corporation led the domestic automotive field, through its five domestic passenger car divisions Chevrolet, Pontiac/Oakland, Oldsmobile, Buick and Cadillac/LaSalle. (Figure 11) Each division, within the expanding General Motors family, embodied a specific income level. Chrysler Corporation also expanded its offerings to include Plymouth, De Soto, Dodge and Chrysler. Like their equivalent at Ford Motor Company, both General Motors and Chrysler provided dependable trucks at different price levels.

In the early 1920s, few domestic manufacturers came close to equaling the highly profitable Ford Motor Company. However, that did not prevent rival automakers from trying to compete against this Detroit giant. In reality, many of them posed a direct challenge to Ford as they continually perfected their-own unique business campaigns. The field was still wide-open to insightful independents as long as they could withstand the unyielding economic and marketing pressures exerted on them by other, equally proficient contenders. Part of the success enjoyed by many maverick brands, at the beginning of the 20th century, rested in their ability to purchase car parts and related operating system components from a wide number of independent suppliers at reasonable cost. That became increasingly more difficult by the mid-1920s. The trouble arose when Detroit’s Big Three started to purchase those successful suppliers. Once they were absorbed into the larger corporate fabric then those new subsidiaries spent most of their time supplying their parent companies with the thousands of accessories and car parts they needed.

That business shift, away from primarily serving individual consumers and small to medium-sized automakers towards working full time for Detroit’s Big Three, hurt independent carmakers immeasurably. Those well-publicized mergers did not preclude smaller auto producers from still purchasing many of their components and parts from those previously independent distributors. However, getting the required products, in a timely fashion, increasingly presented a formable business challenge for smaller car producers. It took much longer to get orders processed than had been the case earlier. Cost considerations and timing played crucial roles in determining which independents would survive, and which ones would not. Throughout the 1920s, basic car components such as self-starters exhaust systems and electric lights remained inexpensive for competing small manufacturers especially when those companies bought those items in bulk. However, volume buying, in itself, did not guarantee deep discounts or speedy delivery once Detroit’s Big Three absorbed those auxiliary companies. The advent of new safety devices such as front wheel brakes and semi-shattered proof windshield glass posed special problems especially for smaller domestic automakers with only limited financial resources.

For example, installing a new brake system in a vehicle represented much more than just purchasing the desired brake kit and accompanying special pads. Being able to mount that brake system properly meant that company engineers must engage in the difficult task of not only redesigning their automobile to accommodate that new system; but also, readapting both the front and rear shock absorbers and springs to conform to it. The manufacturer also must modify front axels, struts, steering and tires to meet these new standards. A costly venture anytime, that kind of extensive redesigning required careful planning and plentiful resources upfront. Any major modifications to the underside of an auto might also adversely affect its engine performance. It was a guessing game. In the final analysis, any radical engineering changes, initiated by independent manufacturers, had to produce an immediate upsurge in car sales in order to ensure and sustain future profits. Any appreciable sales increases would also help corporate executives to legitimize such high costs upfront.

Costly engineering requirements notwithstanding, corporate officials in charge of operating independents, throughout the 1920s, waged an ongoing battle with their accounting staffs when it came to setting aside important funding for much needed research and development. In most instances, corporate accountants strongly opposed any major changes to current business practices especially when they involved radical alterations to the vehicles they had been manufacturing for many years. Their astute accountant staff often opposed the idea of regularly redesigning their automobiles in a vain attempt to keep pace with Detroit’s Big Three. They claimed that such rash business action by the board might prove far too expensive over time. Accountants would only acquiesce to corporate demands for change when board members showed them conclusively that their company would profit measurably from pursuing such a bold financial undertaking. Corporate accountants traditionally held fast to proven business principles. Their reluctance to acknowledge that they might be wrong often placed executives in very embarrassing situations especially when those same officials had to face the grim economic prospects that their company may be losing money rapidly. That earlier realization only intensified in the 1930s as national business conditions worsened.

Another pressing matter affecting many independents concerned the amount and kind of accessories available on their vehicles. Expensive cars often included a multitude of desirable accessories whether the buyer ordered them or not. Those special options were part of the overall price of the automobile with no exclusions or exemptions. In the 1920s, smaller auto manufacturers rarely adopted such a bold business tactic, too many potential loopholes in following such a strategy. Instead, they offered basic accessories at no additional cost to the buying public as well as provide a number of highly desirable extras as part-and-parcel of more expensive optional packages. Dealerships liked that arrangement very much since the markup on accessories, even in those days, was very high.

By the early 1920s, local savings and loan institutions offered a wide spectrum of car loans. Those highly profitable loans led local dealerships to offer similar packages for their many preferred customers. Installment buying gained greater popularity once local dealers discovered that financing automobiles in-house was potentially more lucrative than selling large volumes of new automobiles and trucks for cash. Many local financial institutions encouraged dealership loan packages by providing participating dealers a small percentage of the interest charged on each-and-every loan they oversaw. This translated into additional profit for those distributors involved. [31]

Dealers also quickly realized that the more costly vehicles delivered a much higher profit potential than cheaper models. This led many outlets to offer even better deals for those customers wishing to purchase more upscale models. Trading up through installment buying soon became the rule, not the exception. The miniscule cost difference in terms of the initial down payment and monthly payments made trading up very desirable especially for the newly emerging middle class buyer. Beginning in the 1920s, the prevailing thinking among many customers was why not drive a more luxurious model since it cost only a few cents more per month when compared to the cheaper version of the same make. Studebaker utilized that very business tactic to its advantage by offering its Big Six Sedan for only $840 down with 12 convenient monthly payments of $150.30. (Figure 12) Similar credit packages stimulated new car sales everywhere as thousands of Americans enjoyed the many advantages of owning a quality built domestic automobile at a reasonable fixed monthly cost.

The economic devastation wrought by the Great Depression of the 1930s affected everything. With unemployment topping 25% in 1932, and with no prospects of significant economic improvement in the immediate future, the average U.S. family found it increasingly difficult to survive financially. The election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt as this nation’s 32nd President, in November 1932, and the subsequent reform legislation his administration introduced, primarily through the New Deal, may have offered some temporary relief to some Americans; however, it failed to stimulate the national economy for any prolonged period. Growing economic and social unrest abroad, occurring simultaneously with tariff restrictions on more than 20,000 items through the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, only made the situation worse. [32] A short-lived upturn in the national economy in 1937 offered a glimmer of hope for some. Unfortunately, that newfound optimism rapidly turned to pessimism based on a sudden reversal in the national economy prompted by major labor unrest that occurred that same year. It took America’s entrance into the Second World War before the national economy fully rebounded.

Domestic automobile manufacturers did not fare much better even though some leading companies made some major engineering advances during those trying years. Automatic transmissions, built-in car trunks, hydraulic brakes and gearshifts placed on the steering column led that list of those advancements. (Figure 13) Improvements, like those, not only led to more agile and safer automobiles generally; but also, encouraged the adoption of even more efficient assembly line methods. Analysts, at that time, projected that the major breakthroughs would inevitably yield high profits once full prosperity returned. Regrettably, it was not happening fast enough for Detroit’s Big Three. The Great Depression of the 1930s brought economic misery for many engaged in the manufacturing and selling of domestic automobiles. The longer it dragged on the more likely the majority of carmakers would face the prospects of either bankruptcy or a hostile takeover. Neither option had much appeal to stakeholders who had witnessed a dramatic drop in sales for both new and used cars during the first half of the 1930s.

Many of the automobile advertisements during that crucial decade reflected that negative mood. For example, Cleveland’s Peerless Motor Company, at 9009 Carnegie Avenue, offered sensational trade-in allowances for its new Peerless Eights in 1931. It also provided low down payments and special monthly payments extended for a year or longer whenever necessary. Other special incentives included free accessories, free lube and oil changes, free driving lessons and a 90-day new car guarantee against mechanical imperfections. That company would do almost anything to stimulate new car sales. They were not alone in their thinking.

Oldsmobile relayed a heartfelt message to prospective buyers in January 1931. The advertisement announced that its all-new Viking models would continue to uphold the high quality standards and workmanship that had made that car famous. In fact, Oldsmobile officials planned to utilize the full resources of the General Motors Research Laboratories, Proving Grounds and Fisher Body to achieve its goal.[33] Regrettably, repair services, not new car sales, kept the majority of dealerships financially afloat during those most unsettling economic times. In fact, those owning and operating autos increasingly relied on their local distributors to supply them with the best maintenance and repair service available at the cheapest possible price. In desperation, some outlets offered money-strapped customers free repair service. They considered it the right thing to do under these most unusual circumstances.

The growing number of used car sales throughout the 1930s reflected this growing desperation. Longer showroom and service hours along with pleas made by dealers for customers not to wait any longer before purchasing their next used car fast became the rule. [34] In March 1930, Cleveland’s Bashaw-Oakland Motor Company reminded perspective used car buyers that it provided a full written guarantee on all its vehicles costing more than $300.[35] The Ohio Buick Company, that same year, told its many loyal customers to “Buy with Confidence.” [36] B.W. Blaushild Motors Dodge-Chrysler boasted that “As Cleveland’s Largest Dodge Dealer I (Bernie Blaushild) Can Afford to Sacrifice Profits for Volume!” [37] Markad Ford, at the corner of East 21st Street and Chester Avenue, offered a bona-fide, money back guarantee on all used cars it sold. Furthermore, if the owner of a recently purchased auto, valued at more than $200, was in anyway dissatisfied with that vehicle then he or she could return it for a full refund. Markad Ford also offered special financing for veterans of the First World War through Ford Motor Company Universal Credit Service. [38]

The 25 Greater Cleveland Chevrolet dealers provided great used car deals in 1938. They claimed to have the make and model you wanted at the best possible price. Those automobiles were “Guaranteed OK Used Cars.” [39] Southeast Chevrolet, at 8815 Broadway Avenue, boasted of having the best deals on used cars for 1941. No down payment, no consigners and no cash upfront would put you into one of its many top quality used cars today. That dealership would accept your present car as a trade-in regardless of its condition. Monthly payments for those used cars were only $25. [40] As stated earlier, the harsh economic realities of the Great Depression of the 1930s set in very quickly. National auto sales, in 1932, plummeted to a new all-time low of 1,103,557. A few small manufacturers, such as the American Austin and Crosley, attempted to capitalize on this dwindling market by introducing their-own inexpensive line of vehicles. Their cars cost $400 and $850 respectively. Known as bantams, they sold well initially. However, with few options and only mediocre engine performance their success did not last long. The American Austin continued to produce cars through 1941, while Crosley stayed in business until 1952 when General Tire and Rubber purchased it.