Chapter One : Foundations of the Modern Middle East

Part 7. Nineteenth Century Middle East

Middle Eastern Reforms in the Nineteenth Century

Painting by Antoine-Jean Gros of Napoleon’s victory at the Battle of Aboukir in Egypt

By the time the nineteenth century dawned, the Ottoman Empire was well on its way to becoming “the Sick Man of Europe,” as it would soon come to be known among Europeans. The century began with the French in occupation of one of the most important Ottoman provinces, Egypt. Napoleon had conquered Egypt in 1798, in an effort to cut off British access to India via the Middle East. The French general seems to have even had ambitions of invading India himself, but his plans were brought to nothing after the British destroyed his fleet at the Battle of Aboukir Bay later that same year. When the French attempted to take Syria a few months later, the British and Ottoman armies joined together to defeat Napoleon’s forces once again. His plans frustrated, Napoleon slipped away by night to return to France, leaving his army stranded in Egypt for two more years until an agreement was negotiated in 1801 for the French troops to finally evacuate.

The French invasion may have been turned back, but the clear lesson from the incident was that any major European power could invade any Middle Eastern country at any time and the only force that could drive them out was the army of another European power. The impact of this realization was twofold:

1) The Middle East became a site of complex Western negotiations for the remainder of the nineteenth century. Over time, the British would decide that it was in their best interests to prop up the Ottoman Empire, if only to prevent Ottoman lands from falling into the hands of the Russian Empire. The Russians had already captured some significant Ottoman territory to the north of the Black Sea and were pushing down into the Caucasus and towards Iran via Central Asia. It was this move from Central Asia that really concerned the British, as it created fear that the Russians might horn in on their precious colonial possessions in India. It was in order to prevent such an occurrence that the British twice invaded Afghanistan during the nineteenth century (and twice were defeated there). The political and diplomatic maneuvers in this region by the British and Russian Empires became known as the “Eastern Question” or the “Great Game.”

2) The major Middle Eastern powers, particularly the Ottoman Empire and Egypt, became convinced that their only hope for survival was to implement Westernization within their realms as quickly as possible. Their initial emphasis in Westernization focused on updating their military. This made sense since it was on the battlefield that the Middle Eastern states were losing wars, and the military imbalance between East and West was what made them feel most vulnerable. However, as it turned out, Middle Eastern governments could not just pick and choose what aspects of Western civilization they wanted to adopt. The more entangled they became with their Westernization projects, the more widespread Westernization became in the Middle East, leading to a number of unintended consequences. In fact, Middle Eastern responses to Western dominance can be categorized into four areas, presented below.

The first of the four Middle Eastern responses to Western dominance can be labeled as “Top-Down Reform.” This includes the efforts made by Middle Eastern rulers to implement limited Western reforms within their states in an attempt to better centralize their power and catch up with the West so as to protect their realms from further Western incursions. As mentioned above, the two main places that we will focus our attention on are the Ottoman Empire and Egypt. In Egypt, the departure of French troops left a power vacuum, into which stepped an Ottoman adventurer by the name of Mehmet (or Muhammad) Ali. Mehmet Ali originated in Albania and was promoted through the Ottoman system until he reached the rank of second in command for the Albanian contingent of soldiers brought into Egypt in 1801 upon the evacuation of French troops. Mehmet Ali was a shrewd politician, and he managed to outmaneuver his opponents to achieve the rank of Ottoman governor in Egypt by 1805. Over the next several years, Mehmet Ali went about eliminating opponents and reorganizing the military with the help of French military advisors. Soon he had managed to assemble the most effective fighting force in the Middle East.

Other reforms implemented by Mehmet Ali included revamping education along Western lines, reorganizing landownership, developing the cotton industry within Egypt, and beginning industrialization projects. His goal was to obtain independence from the Ottoman Empire and to establish a hereditary dynasty in Egypt. He also attempted to centralize the Egyptian economy and streamline the administration so as to turn Egypt into a major regional power. Eventually his reforms and wars of expansion threatened the continued existence of the Ottoman Empire, and the British, Austrians and French joined together to drive his troops back to Egypt in 1840. His expansionist plans defeated, Mehmet Ali was still able to obtain a concession to establish a hereditary dynasty over Egypt. The descendants of Mehmet Ali would continue to rule in Egypt until 1952.

In the Ottoman Empire, “Top-Down Reform” was pushed by two Ottoman sultans, Selim III and Mahmud II. Selim, who ruled the Ottoman Empire from 1789-1807, tried to implement reforms through his program entitled nizam-i jedid (the New Order). However, powerful forces in the military, specifically the Janissary regiments, got wind of Selim’s plans and forced him out of power. His successor, Mahmud II (r. 1808-1839), had the same goals, but he pursued them in a more deliberate and underhanded manner. By 1826, Mahmud had managed to develop a separate military force loyal to himself. Provoking the Janissaries to revolt, Mahmud had them massacred in June 1826 and “the military institution that had once been the foundation of Ottoman power was destroyed forever” (William L. Cleveland and Martin Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East, Fourth Edition, 78).

However, by doing this, Mahmud left his government functionally without an army, and it would take some time to rebuild the military along the revised lines that he had envisioned. In a showdown with Mehmet Ali’s troops in 1839, Mahmud’s forces were bested and only direct intervention by the British and Austrians prevented an Ottoman collapse. The empire had been saved, but at the cost of considerable financial concessions to the European powers. Known as “capitulations,” these concessions granted open access for the Europeans to markets throughout the Ottoman Empire, completely free of taxes that Ottoman merchants themselves had to pay to the government. Although the capitulations had been operating in the empire since the sixteenth century, these new concessions granted European access to Ottoman markets with almost no restrictions. Such a situation was a financial windfall for the British and French but disastrous to the Ottoman economy. Mahmud II died a few months later and his successors pushed forward with further changes.

The second of the four Middle Eastern responses to Western dominance was modernizing religious reform. Muslims faced the problem that their religion teaches the ultimate victory of Islam over the unbelieving nations, and yet the triumph of the European colonial powers over most of the Muslim world seemed to contradict this long-held belief. As religious scholars struggled with this reality, they found several ways to respond. The first way was the traditional response, which sought to reinforce established Islamic teachings, while withdrawing as much as possible from contact with Western influences. This “bury your head in the sand” approach became harder and harder to implement as colonial powers continued to extend their reach into more of the Muslim world during the course of the nineteenth century.

In contrast to the traditional response, a number of Muslim thinkers and scholars opted to engage the Western world directly. This group argued that the problem was not with Islam but rather that it was with Muslim leadership which had failed to keep pace with the times. During the first six centuries of Islam, these scholars maintained, the religion had shown a great adaptability and energy for studying God’s world and making advances in science and technology. The problem was that Muslim scholars, particularly after the Mongol conquests of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, had become defensive and inward looking. They had adopted the “safe” approach of simply repeating the teachings of their predecessors, allowing Muslim societies to become stagnant and to retreat from engaging in ground-breaking research in science and technology as their predecessors had done. What was needed was to “reopen the door to ijtihad” (rational thinking) and to reapply the fundamental principles of their faith in new ways, allowing the Islamic world to adapt to modern times and update its society accordingly. To do so would not be to go against Muslim teachings; rather it would be to imitate the practices of their forefathers (salaf) who demonstrated this same willingness to engage with the world around them. Leading scholars of this type of modernist Islamic thought included Sayyid Ahmed Khan of India, the traveling scholar Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (who is thought to have been of Iranian origins) and the Egyptian Muhammad Abduh.

The third Muslim religious response to Western dominance is also the third of the four Middle Eastern responses mentioned above, the revivalist approach. Revivalists agreed with the modernists that the problem was not with Islam – it was not as if Islam was somehow a backwards and fatalistic faith, as Western colonialists and missionaries were saying. Rather, the problem was that Muslim leaders had failed in their duty to properly lead Muslim societies, creating a susceptibility to dominance by the aggressive Western colonial powers. Their answer to this problem, however, was very different from that of the modernists. Whereas the modernists wanted to engage with the outside world and were willing to adapt Western practices to apply them in Muslim societies, the revivalists rejected everything from the West as being of infidel origin and therefore polluted. The revivalists felt that what was needed was to return to the examples of Muhammad and the first Muslims, but rather than focus on principles (which could be updated and applied to the new realities of the modern world) the revivalists focused upon more literalistic readings of the Qur’an and hadith (traditions of the Prophet Muhammad).

Leading revivalists were usually religious scholars or Sufi (mystical) leaders who arose in rural areas (often in desert communities or the West African Sahel). These leaders would usually pattern their careers upon the career of the Prophet Muhammad. Even though they grew up in Muslim societies, these leaders believed that their societies had become apostate, i.e. that they had fallen away from “true” Islamic practices and had given way to superstition and/or Western “infidel” influences. The revivalist leaders would often begin their careers (after years of studying the Qur’an and traditional religious teachings) by preaching against their own societies and calling upon Muslims to repent and return to the original zeal for Islam that they had lost. Usually this preaching would attract some converts but also opposition from societal leaders who did not appreciate being called apostates.

The revivalist leaders and their devoted followers would then retreat to smaller communities in the desert or other rural areas where they were accepted not only as religious but also as political leaders, much as the Prophet Muhammad had fled from Mecca to Medina to establish the first Islamic community. After several years in these new communities, the religious leaders would launch holy war (jihad) against the wider apostate society. Often they would succeed in conquering large areas in the name of their revivalist faith, in which they would implement their literalist understandings of shari`a (Islamic) law. In many cases these utopian communities saw themselves as forerunners for a revival that they expected would spread throughout the Islamic world, and their revivalist movements would often come into direct confrontation with Western colonial powers. Among the many successful revivalist movements of the nineteenth century were the Wahhabis of Arabia, the Sanusi movement of Libya, the Mahdist movement of the Sudan, and the holy warriors led by Amir Abd al-Qadir in Algeria.

The fourth Middle Eastern response to Western dominance was much like the first and second responses in that it looked to the West for inspiration in the renewal of Middle Eastern societies. Specifically, this group bought into Western ideas of nationalism, i.e. the belief that specific groups of people form “nations” based upon a common identity, usually ethnic, historical, linguistic or religious. Western ideals of nationalism were often linked with democratic and constitutionalist concepts, i.e. the belief that the principles of statehood called for participation of “the people” rather than just certain elite power holders who had been designated by God to lead, and that the principles of governance were best set out concretely in constitutions that protected the rights of individuals and provided guidelines to hold leaders accountable for how they govern. These ideas were based upon concepts arising from the European Enlightenment and which had been applied in the eighteenth century American and French revolutions.

As nation-states were established throughout Europe, ideas of nationalism spread into the European colonies, especially as bright young leaders from colonial countries often traveled to Paris or London to study in Western universities and learn Western ways. They returned to their homelands inspired to implement nationalist principles in their own countries. Ironically enough, their Western inspired nationalism often created within them a desire for independence from Western colonial dominance, the same sorts of desires for freedom that American colonists, for instance, felt regarding their ties with Great Britain during the second half of the eighteenth century.

Nationalist and constitutionalist movements broke out throughout the main countries of the Middle East during the last few decades of the nineteenth century. In Egypt, a military man named Ahmad Urabi led a revolt against the Egyptian government, which had gone into debt to Western financiers in its attempts to modernize Egyptian society in a “top-down” manner. Urabi’s revolt took place in 1881 but was crushed by a British invasion in 1882. The British had become concerned that a nationalist Egyptian government would not prioritize paying off the debts it owed to Western powers. The result was a puppet Egyptian regime dominated by the British in an informal protectorate that would last until 1952.

In Constantinople (Istanbul), constitutionalists forced the sultan to agree to the establishment of a written constitution and an elected representative body in 1876. However, the constitution was set aside in the midst of an Ottoman military defeat to Russia in 1878, and the sultan Abdul Hamid II ruled as a dictator for the next thirty years. In 1908, following more Ottoman military defeats, a group known as the Young Turks overthrew the government and re-established the Ottoman constitution and representative government. A similar constitutionalist movement took place in Iran during the first decade of the twentieth century.

However, these Middle Eastern responses to Western dominance would all fail to obtain their ultimate objective – parity with the West and self governance. “Top-Down” reforms and Islamic modernism would successfully remake Middle Eastern states in many areas, including politics, education, culture, and religion. However, they were less successful in breaking free from Western control. The vast expenses required to remake Middle Eastern societies resulted in substantial debts to Western financiers, which led directly to further Western dominance. Islamic revivalist movements, while achieving some success at establishing independent principalities, would all be defeated militarily by Western colonial powers or Top-down reformers by the end of the nineteenth century. Even the constitutionalists were unable to achieve their aims for the same reasons – their nationalist/constitutional aims ran contrary to the interests of Western powers, who made sure that they failed to obtain the autonomy that they desired.

Primary Sources

The documents linked below are all Ottoman reform documents from the 19th and early 20th centuries. The first document is the Rescript of Gulhane of November 3, 1839, shortly after the European powers had rescued the Ottomans from the armies of Mehmet Ali. The second document is the Rescript of Reform – Islahat Fermani of February 18, 1856, issued shortly after Britain and France had assisted the Ottomans against the Russian Empire in the Crimean War. It ushered in the Tanzimat reforms. The third document is the Ottoman constitution of December 23, 1876, which established the first European style constitution in the history of the empire, although it would shortly be put on hold by Sultan Abdulhamid II. The fourth document is the Revised Articles of the 1876 constitution, established in August 1909 after the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 had restored constituionalists into power in the Ottoman empire.

https://www.anayasa.gen.tr/gulhane.htm

https://www.anayasa.gen.tr/reform.htm

https://iow.eui.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2014/05/Brown-01-Ottoman-Constitution.pdf

https://www.anayasa.gen.tr/1909amendment.htm

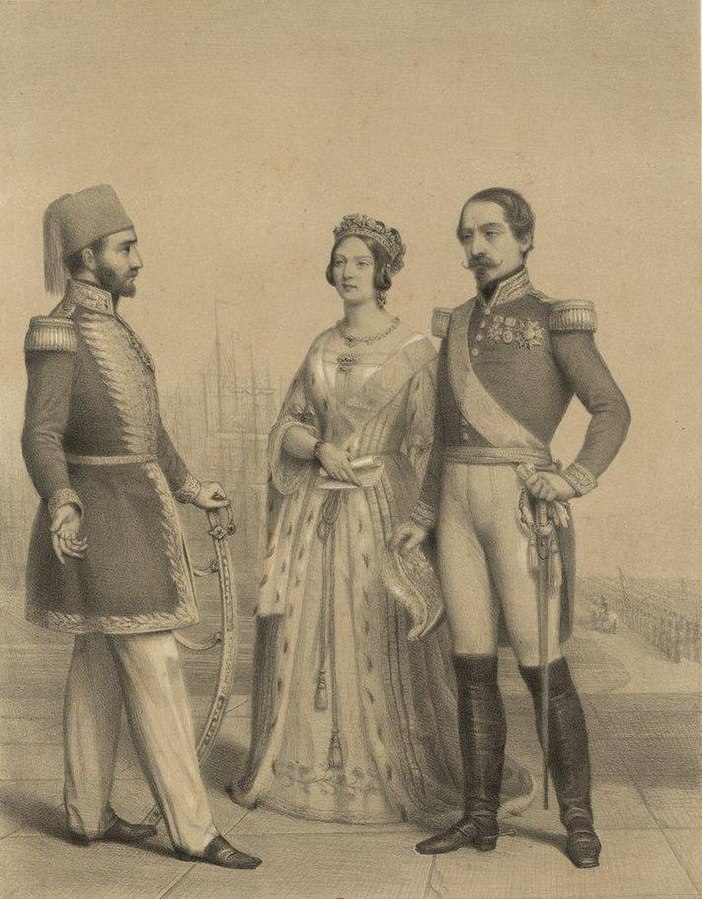

Image below: Ottoman Sultan Abdulmejid (r. 1839-1861, who oversaw the Tanzimat reforms, meets with Queen Victoria of England and Emperor Napoleon III of France.