Chapter Three: Faith and Religious Identity

Part 3. Religious Diversity

Within each of these religions there is immense diversity. For example, many don’t know how diverse the state of Israel is in reality. Not only Jewish, Israeli citizens can be Muslim, Druze or Christian. They can be Arab, in addition to Jews of every ethnic heritage both in Israel and around the world. In general, Jews with European heritage are called Ashkenazi Jews, while Jews from the Middle East are called Sephardic Jews, or Mizrachim. The diversity is hardly limited to those two categories, however. Individuals from every continent and cultural background make up the population. Core tenets from the Torah are shared by all Jewish communities, but the practices surrounding them vary from community to community.

Likewise, there is much diversity within Muslim-majority countries, and within the global Muslim population as a whole. Several communities follow religious practices which emphasize different aspects than mainstream Islam, have separated into a theology, or combine theologies with other religions:

- ‘Alawi Shi’ism: a form of Shi’ism, but more centered on venerating ‘Ali. There are many communities in Syria and Turkey (Bashar al-Assad, the President of Syria, is an ‘Alawite)

- The Druze Faith: Islamic foundation, but radically different practices and theology

- The Bahai’ Faith: Related to Shi’i Islam, recognizing a prophet who came after Muhammad, however.

- Yazidism; Combination of Islam, Zoroastrian and other traditions.

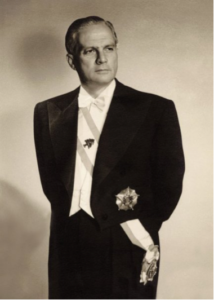

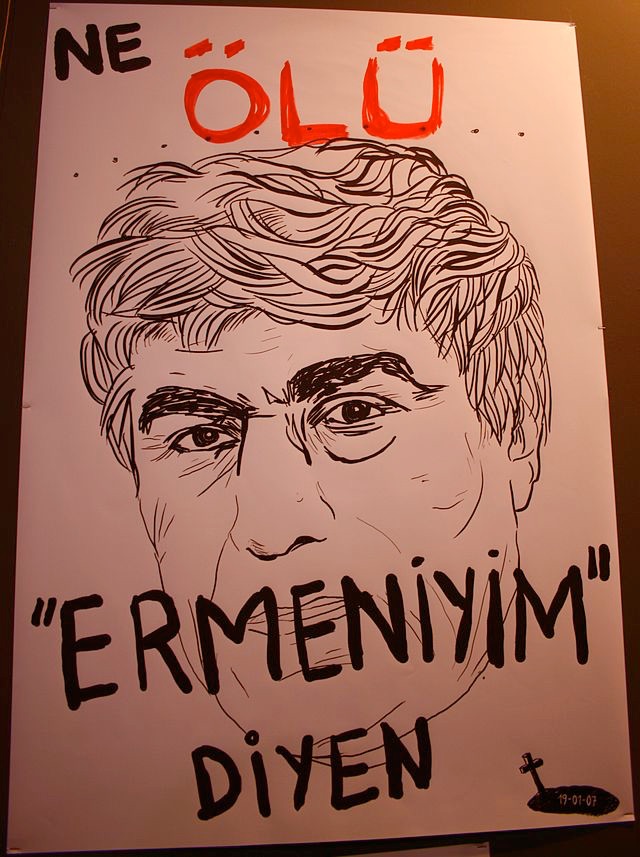

These facets of diversity show how many minority groups there are, and have been, in the Middle East, and how problematic it can be to generalize about the religious outlook of a country, or even a small area within a country. In the U.S. and other countries around the world, many Middle Eastern immigrants represent minority communities of the Middle East (see image gallery, left, of celebrities with diverse Middle Eastern religious and cultural identities).

The minority communities of Jews and Christians used to be a much larger percentage in most of the countries of the Middle East. Post-World War I European interventions often had the effect of concentrating ethnic-religious groups into specific countries. For example, the Greek Christian/Muslim Greek population exchange of 1923, which was a continuation of the Christian/Muslim migrations that resulted from the Greek/Turkish war. At the same time, war devastated many other communities who were expelled, such as the Armenians. These trends intensified as nation states developed out of prior colonies/mandates, and other territories impacted by European imperialism.

The violent demographic shifts that occurred in the Middle East over the course of the 20th century created, and continue to create many new Middle Eastern diaspora communities worldwide. The effect has been dwindling minorities in countries which lost much of these populations, and the underrepresentation of nations which did not succeed in forming a nation-state country of their their own. The Kurds a currently in the headlines as a prominent stateless nation, and a community/ies with complicated relationships with the governments Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran, where Kurds reside.

The creation of Israel was another influence on the demographic make-up of the Middle East. It drew large Jewish populations from many of the Middle Eastern countries, especially Morocco, Yemen, and Iran. Other countries were affected, as well. Jewish communities remain in those countries, but their numbers are severely diminished. For example, Afghanistan used to have a thriving Jewish population, but there is now only one remaining Jewish resident of the country (Englehart,2009).

Christian communities in Middle Eastern countries are perhaps the least represented communities in mainstream information sources. Assyrians, Armenians, Copts, and other cultural groups that are predominantly Christian, are increasingly minoritized in Muslim-majority countries while at the same time many of their communities in diaspora. Only Armenians have their own nation-state. At the same time, they are more prominent here in the U.S., where we are writing this book, because communities make up a larger percentage of the total number of individuals who have emigrated from the Middle East to the U.S., than do Muslims. Therefore, it is more likely for one to meet a Christian with Middle Eastern heritage in the U.S. than in the region.

“RosieMalek-Yonan.jpg” by RMY, from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

“Paula Abdul 2007.jpg” by Toglenn, from Wikipedia, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0